BUDDHIST MONKS

Taungkalat temple and monastery in Myanmar Buddhist religious life has traditionally centered around “sanghas” ("Orders of Disciplines"), a word used to describe communities of monks who preserve and transmit Buddha’s teachings and live at monasteries. Buddhists believe that the spiritual quest of monks benefits the entire community and their rituals bring prosperity and protection.

The monk ideal is most important in Theravada Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhism. Monks have traditionally been an important part of religious life in Theravada-dominated Thailand, Laos Myanmar, and Sri Lanka and in Tibet. Even today in these places, teenage boys and young men boys are expected to serve as monks for period of some months, ideally after they finish school and before they get married or start a career. Most towns and even villages have own monasteries connected to local temples. The families of monks earn large amounts of merit. In According to the BBC: "Theravada Buddhism, monks are considered the embody the fruits of Buddhist practice. Monks' responsibility is to share these with lay Buddhists through their example and teaching. Giving to monks is also thought to benefit lay people and to win them merit."

Monk culture is not as widespread in China and Japan and other places where Mahayana Buddhism dominated because Mahayana Buddhism does not place as much importance on the monk ideal as Theravada Buddhism and because political pressures, namely Communism, and modern life have discouraged men from seeking to become monks.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion

See Separate Articles: BUDDHIST MONK LIFE: INITIATION, DUTIES, CLOTHES AND BEGGING factsanddetails.com ; MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; NOVICE MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM AND THEIR ORDINATION factsanddetails.com; FOREST MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; CHINESE BUDDHIST TEMPLES AND MONKS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN MONKS AND LAMAS factsanddetails.com; factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“What is the Sangha?: The Nature of Spiritual Community”

by Sangharakshita Amazon.com ;

“Teachings of a Buddhist Monk” by Ajahn Sumedho , Marcelle Hanselaar, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Three Japanese Buddhist Monks” (Penguin Great Ideas)

by Various and Meredith McKinney Amazon.com ;

“Adventures of the Mad Monk Ji Gong: The Drunken Wisdom of China's Famous Chan Buddhist Monk” by Guo Xiaoting, John Robert Shaw, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Silk Road Journey With Xuanzang” by Sally Hovey Wriggins Amazon.com;

“Xuanzang: China's Legendary Pilgrim and Translator”by Benjamin Brose Amazon.com;

“Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Faxian and James Legge Amazon.com;

“The Sound of Two Hands Clapping: The Education of a Tibetan Buddhist Monk”

by Georges B. J. Dreyfus Amazon.com;

“From a Mountain In Tibet: A Monk’s Journey” by Yeshe Losal Rinpoche Amazon.com;

“The Life of a Tibetan Monk” by Geshe Rabten Amazon.com;

:The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk” by Palden Gyatso Amazon.com;

“Himalayan Hermitess: The Life of a Tibetan Buddhist Nun” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer Amazon.com;

“Labrang Monastery: A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709-1958" by Paul Kocot Nietupski Amazon.com;

“Sera Monastery” by José Cabezón and Penpa Dorjee Amazon.com

Sangha: the Buddhist Monk Community

The Buddhist monk community is referred to as the “Sangha”. “The word ‘Sangha’ means those who are joined together, thus a Community. However, "Sangha" does not refer to the entire Buddhist Community, but to the two kinds of Communities within the larger Buddhist Society. They are: 1) The Noble Sangha (Ariya Sangha), the community of the Buddha’s true disciples; and 2) the conventional Sangha, fully ordained monks and nuns. In principle, the word Sangha includes bhikkhunis - that is, fully ordained nuns — but in Theravada countries the full ordination lineage for women has become defunct, though there continue to exist independent orders of nuns.

On the Sangha,the Theravada Buddhist scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi wrote: “The Buddha’s dispensation is founded upon three guiding ideals or objects of veneration: the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha. The Buddha is the teacher, the Dhamma is the teaching and the Sangha is the community of those who have realized the teaching and embody it in their lives. These three are together called the Three Jewels or Triple Gem. They are called the Three Jewels because for one who is seeking the way to liberation, they are the most precious things in the World. The Buddha established the Sangha in order to provide ideal conditions for reaching the ariyan state, for attaining Nibbana. [Source: Virtual Library Sri Lanka lankalibrary.com ]

“The bhikkhu, the Buddhist monk, is not a priest; he does not function as an intermediary between the laity and any divine power, not even between the lay person and the Buddha. He does not administer sacraments, pronounce absolution or perform any ritual needed for salvation. The main task of a bhikkhu is to cultivate himself along the path laid down by the Buddha, the path of moral discipline, concentration, and wisdom.”

See Separate Article: SANGHA (BUDDHIST MONK COMMUNITIES) AND MONASTERIES factsanddetails.com

Purpose and Aims of a Buddhist Monk

On one hand monks are perceived as sort of mini-Buddhas in that not only are they seeking enlightenment for themselves but devote a great amount of energy and devotion to teach and inspire and instruct other to purse the Way of The Buddha. One the other hand, they remain seekers of knowledge themselves, or ones who has not found nirvana but are still striving for and have things to learn and achieve, and are advancing in a gradual, step-by-step process.

Monks are not removed from world. They spend a large amount of their time in monastery schools teach children reading and writing as well religion. This is one reason why many Buddhists countries have traditionally had a high rate of literacy. Buddha himself chose not spend his time on Earth in an enlightened state; rather he decided to be in the real world, teaching people about Buddhism.

Tibetan prayer drums

The first reward fir a fully-realized monk is to escape being reborn as an animal or a ghost or caste into a Buddhist hell. This is regarded as the first stage of entering the stream that flows towards nirvana. The next stage is to reach such a level that attachment to world is a minimal and one has to endure only one more human birth to reach nirvana. In the last stage the monk experiences nirvana and transcends life on earth, breaks the cycle of reincarnation and has no reason to be reborn.

Arhats and the First Buddhist Monks

The first Buddhist monks were called “arhats” . They were regarded as men well on their way down the path to seeking nirvana. One passage from an early Buddhist text goes: “Ah, happy indeed the Arhats! In them no craving’s found. The “I am” conceit is rooted out; confusion’s net is burst. Lust-free they have attained; translucent is the mind of them. Unspotted in the world are they...all cankers gone.”

The first five ascetics who became the first monks under The Buddha were joined by 55 others. They together with The Buddha are known as the 61 arhats. The were ordained by The Buddha by repeating the simple phrase: “Come monk; well-taught in the Dharma; fare the attainment of knowledge for making a complete anguish.” Others that came later were ordained after cutting their hair and beard, donning a robe and uttering three times: “I go to Th e Buddha for refuge, I go to Dharma for refuge, I go to the sangha for refuge.” This ritual remains the basis of the Theravada monk ordination process today.

Anada was The Buddha constant companion. His two chief disciples—Sariputta and Moggallana — were two ascetics who for were known for seeking the Dharma to deathlessness Mahkaccan was ranked the highest for his ability to interpret the Buddha’s brief statements.

In the years that followed The Buddha gave more sermons and instructed his disciples on methods that could be used to discover the eternal truth. The Buddha spoke on a number of subjects and often used stories about monkeys, wealthy lords and fishermen and similes such as comparing “hold of the mind” to “trainer’s hook” used to pacify a “savage elephant” to make his points. He presented himself as a man not a god of myth and thereby argued that anyone could achieve what he had done.

See Buddha’s Begging Under BUDDHA’S LATER LIFE: TEACHING, DAILY ROUTINE, BEGGING AND MIRACLES: factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Buddhist parable of the Arhats

Rules for Monks and Nuns in the Tipitaka

The Sutta Pitaka (also referred to as the teachings of the Buddha) of the Tipitaka — the main Buddhist text — contains 227 rules for monks and 311 rules for nuns that advise them on how to handle themselves in certain situations and describes the relationships between the Sangha (monk community) and lay people. The 227 rules for monks is called the Patimokkha. It also details how and why the rules were developed.

The Vinaya (Buddhist Monastic Code) in the Tpitaka is comprised of 1) The Pâtimokkha Nidâna: a ) The Pârâgika Rules, b) The Samghâdisesa Rules, c) The Aniyata Rules, d) The Nissaggiya Pâkittiya Rules, e) The Pâkittiya Rules, f) The Pâtidesaniya Rules, g) The Sekhiya Rules and h) The Adhikarana-samatha Rules and 2) The Mahâvagga, a) First Khandaka (The Admission to the Order of Bhikkhus), b) Second Khandhaka (The Uposatha Ceremony, and the Pâtimokkha), c) Third Khandhaka (Residence during the Rainy Season), d) Fourth Khandhaka (The Parâvanâ Ceremony).

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Dhamma Talks dhammatalks.org

Rules and Lifestyle of Early Buddhist Monks and Nuns

In the early days of Buddhism — and still to a large degree today — any male who was not disabled, sick, a criminal, a soldier, a debtor, or a minor lacking parental consent could enter the order as a monk. The initiation ceremony comprised the renunciation (pabbajja ), the arrival, and the pledge to keep the four prohibitions against: 1) sexual intercourse, 2) theft, 3) harm to life, and 4) boasting of superhuman perfection. [Source: A. S. Rosso,; Jones, C. B. New Catholic Encyclopedia, Encyclopedia.com]

The initiated was bound to observe the ten abstentions from: 1) killing, 2) stealing, 3) lying, 4) sexual intercourse, 5) intoxicants, 6) eating after midday, 7) worldly amusements, 8) wearing cosmetics and adornments, 9) using luxurious mats and beds, and 10) accepting gold or silver. Initiation, abstentions, and vows did not bind a monk for life, but only for the time he remained in the order.

Daily exercises of the monks comprised morning prayers, recitation of verses, outdoor begging, a midday meal followed by rest and meditation, and evening service. Fortnightly exercises consisted in observing a day of fast and abstinence (uposatha ) and in making a public confession of sins (pratimoksa ).

At the request of his aunt and foster mother, Mahaprajapatī, The Buddha founded a second order for nuns. On top of that, he established a third order — for lay people — who were obliged only to abstain from killing, stealing, lying, intoxicants, and fornication. But they were exhorted to practice kindness, clean speech, almsgiving, religious instruction, and the duties of mutual family and social relations.

Renunciation and Deliverance of Buddhist Monks

Bhikkhu Bodhi wrote: “The key move that charactrizes the act of becoming a monk is renunciation, going forth from the household life into homelessness. Homelessness is not absolutely essential for this work, true renunciation is an inner act, not a mere outer one. But the homeless life provides the most suitable outer conditions for practising true renunciation. But anyone who has correctly grasped the drift of the Dhamma will see that the path of renunciation follows from it with complete naturalness. The Buddha teaches that life in the world is inseparably connected with dukkha, with suffering and unsatisfactoriness, leading us again and again into the round of birth and death. [Source: Virtual Library Sri Lanka lankalibrary.com ]

“The reason we remain bound to the wheel of becoming is because of our attachment to it. To gain release from the round we have to extinguish our craving. That is the highest renunciation, the inner act of renunciation. But to win that attainment we generally must begin with relatively easy acts of renunciation, and as these gather force they eventually lead us to a point where we no longer are attracted to the pleasures of the world. When this happens, we become ready to leave behind the household life, to enter upon homeless state in order to devote ourselves fully to the task of removing the inner subtle clinging of the mind.

If a person finds himself unsuitable for monastic life he is free at any time to leave the robes and return to lay life without any kind of religious blame attached to himself.

young monks and nuns in Thailand

Buddhist Nuns

At the request of his aunt and foster mother, Mahaprajapatī, The Buddha founded a second order for nuns. The Sutta Pitaka of the Tipitaka — the main Buddhist text — contains 311 rules for nuns that advise them on how to handle themselves in certain situations. Even so, in many places there is no equivalent of the order of monks for women. Women can serve as lay nuns but they are much lower status than monks. They are more like assistants. They can live at temples and generally follow fewer rules and have less demands made on them than monks. But aside from the fact they don’t perform certain ceremonies for lay people such as funerals their lifestyle is similar to that of monks.

There are much fewer Buddhist nuns than Buddhist monks. At one time there was a nun movement in which nuns had a similar status of monks but this movement has largely died out. The Theravada Buddhist scholar Bhikkhu Bodhi wrote: “In principle, the word Sangha includes bhikkhunis — that is, fully ordained nuns — but in Theravada countries the full ordination lineage for women has become defunct, though there continue to exist independent orders of nuns.”

Nuns spend much of their time in meditation and study like other monks. Sometimes nuns shave their heads, which sometimes makes them almost indistinguishable from the men. In some cultures their robes are the same as the men (in Korea, for example, they are grey) and other ones they are different (in Myanmar they are orange and pink). After the head of a Buddhist nun is shaved, the hair is buried under a tree.

Buddhist nuns perform various duties and chores. Nuns-in-training make around 10,000 incense sticks a day working at easel-like desks at a building near the pagoda. carol of Lufty wrote in the New York Times, "The women, all in their 20s and exceedingly friendly...wrap a sawdust-and -tapioca flour mixture around pink sticks and roll them in yellow powder. These are then dried along the roadside before they are sold to the public."

History of Buddhist Nuns

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The issue of female monks has been a consistently contested one, since the Buddha himself reluctantly allowed his aunt Mahapajapati to join the sangha but with the stipulation that female monks (Pali, bhikkhuni) would be subject to additional rules. In practice, though, the lineage of female monastics died out fairly early in the Theravada, and it has only been in the modern era, often as the result of the efforts of Western female Buddhists, that the female sangha has been revived, and even in these cases women monks are sometimes viewed with suspicion and even open hostility. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Nonetheless, in Southeast Asia and Sri Lanka, women monastics have been an important voice and an important symbolic presence. In the Mahayana and Vajrayana schools, as well as in Zen, female monks, although certainly not the norm, are more common than in the Theravada. China and Korea are the only East Asian countries to allow for full female ordination.

Beginning in the early 1980s a move for full female ordination began in Tibetan Buddhism, with the first all-female monastery being built in Ladakh, India, home of many Tibetan Buddhists since the Dalai Lama's exile in 1959. Similarly, Thai Buddhist woman began to organize a female monastic order in the 1970s. In Sri Lanka a German woman, Ayya Khema, began a female monastic order in the 1980s, one that has continued to grow. In 2000 the International Association of Buddhist Women was founded. This umbrella organization brings together the various female sanghas and provides a vital nexus of unity and activism.

Buddhist Sources on Holy Men and Teachers

The religious mendicant, wisely reflecting, is patient under cold and heat, under hunger and thirst, ... under bodily sufferings, under pains however sharp.—Sabbasava-sutta. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

As he who loves life avoids poison, so let the sage avoid sinfulness.—Udanavarga.

Reverence ... is due to righteous conduct.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

The wise man ... regards with reverence all who deserve reverence, without distinction of person.—Ta-chwang-yan-king-lun.

They also, resigning the deathless bliss within their reach, Worked the welfare of mankind in various lands. What man is there who would be remiss in doing good to mankind? —Quoted by Max Muller.

Go ye, O Brethren, and wander forth, for the gain of the many, the welfare of the many, in compassion for the world, for the good, for the gain, for the welfare of ... men.... Publish, O, Brethren, the doctrine glorious.... Preach ye a life of holiness ... perfect and pure.—Mahavagga.

Go, then, through every country, convert those not converted.... Go, therefore, each one travelling alone; filled with compassion, go! rescue and receive.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

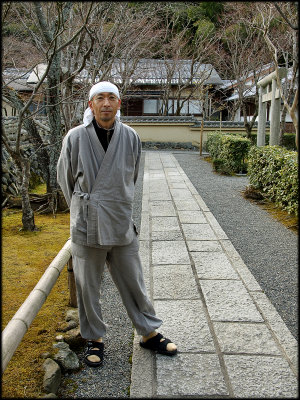

Buddhist Monks and Sex

Temple monk in Japan In Southeast Asia, women are not allowed to touch monks. A pamphlet given to arriving tourists in Thailand reads: "Buddhist monks are forbidden to touch or be touched by a woman or to accept anything from the hand of one." One of Thailand's most revered Buddhist preachers told the Washington Post: "Lord Buddha has already taught Buddhist monks to stay away from women. If the monks can refrain from being associated with women, then they would have no problem."

Buddhist monks in Thailand have more than 80 meditation techniques to overcome lust and one of the most effective, one monk told the Bangkok Post, is "corpse contemplation."

The same monk told the newspaper, "Wet dreams are a constant reminder of men's nature. " Another said that he walked around with his eyes lowered. "If we look up," he lamented, "There it is — the advertisement for women's underpants."

In 1994, a charismatic 43-year-old Buddhist monk in Thailand was accused of violating his vows of celibacy after he allegedly seduced a Danish harpist in the back of her van, and fathered a daughter with a Thai woman who gave birth to the child in Yugoslavia. The monk also reportedly made obscene long distance calls to some his female followers and had sex with a Cambodian nun on the deck of a Scandinavian cruise ship after he told her they had been married in a previous life.

The monk was also criticized for traveling with a large entourage of devotees, some of them women, staying in hotels instead of Buddhist temples, possessing two credit cards, wearing leather and riding on animals. In his defense, the monk and his supporters said that he was the target of "a well organized attempt" to defame him masterminded by a group of female "monk hunters" out to destroy Buddhism.

Greedy Buddhist Monks and Corrupting Influences

Monks sometimes wear Reebox running shoes under their robes and suck on popsicles and smoke cigarettes after the meditation sessions are over. In some monasteries where discipline is particularly lax they can bee seen drinking alcohol at festivals and possessing many more things than their ascetic life ascribes.

A Thai writer named Sulak Sivaraksa told National Geographic's Noel Grove: "Modern life has made virtuous existence very difficult, even for monks. A hundred years ago, monks handled many of the social responsibilities — hospitals, education, moral training. Now the rich go to government universities or to schools abroad. they are losing the Buddhist teachings, and the monkhood is losing its identity."

Temple priest in Japan "Some monks," Sivaraksa said, "began smoking — calling it medicine — and taking drugs and opening bank accounts. The noble truths of Buddhism are being ignored, such as lack of greed and the importance of suffering and humility."

Buddhist monks in particular sects in Japan and Korea are allowed to get married and have children. In Japan, many earn six figure dollar incomes, drive fancy cars, smoke cigarettes and wear three piece suits. The situation has gotten so out of hand in Japan, where greedy monks have been accused of overcharging their customers for funerals, blessings and other services. A funeral mass, for example, averages about $1,500, and the presiding monk often get to keep 90 percent of the fee for himself. [Source: Quentin Hardy, the Wall Street Journal]

Monks and temples have been charged with undereporting their income on their tax returns; established temples sometimes franchise their name to new temples for $3,000 fees; and rich monks usually pass their temples down to their children like feudal lords. A monk at one temple, who earned about $100,000 a year, was fired after he punched out another monk who told him to clean a floor.

An American who spent a year in Japan studying the "deeper meaning" of Buddhism told the Wall Street Journal that "almost nobody knew anything about it." A monk at one temple told him "money is a pretty big part of it." Another told him that "people don't respect you unless you are successful. You've got to have a good car to show you've reached a state of holiness."

See Separate Articles: FAT AND CORRUPT BUDDHIST MONKS IN THAILAND factsanddetails.com and BUDDHIST MONKS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Monastery Tourism

Many Buddhist monasteries and temples have meditation centers that offer instruction to lay people, civil servants, teacherers and tourists. They learn meditation from a master during a two to four week course. Some monasteries have programs that last a few hours, or over night. Some also give massages and do fortunetelling.

In some countries Theravada Buddhist countries such as Thailand, a layperson, or even a tourist but typically a man, may enter a monastery for a short period of time to learn meditation and improve his powers of concentration. While in the monastery, such lay people live according to strict Theravada principles. This means that they try to remain pure in thought and action and go on alms rounds with the monks, observing silence throughout. Alms are donations of food, drink, or other items. Personal possessions are limited to one pair of underwear, two yellow robes signifying discipline, a belt, a razor, a needle, a water strainer, and a bowl for collecting alms. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

During their stay, they are educated in the principles of Buddhism and instructed by the monks in right living. After returning to normal life, lay people often maintain small shrines in their homes, and may go to preaching halls rather than temples to hear teachings, and visit holy sites on pilgrimages.

See Eiheiji Temple Under KANAZAWA AND FUKUI in Japan factsanddetails.com

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024