BUDDHIST ART

Sakyamuni Buddha at Bodhgaya

Most Buddhist art consists of depictions of Buddha, usually in statue from and to lesser extent in murals, frescoes and other paintings. The way in which Buddha is depicted often says more about the culture that created it than about Buddhism itself.

There are lots of symbols and codes in Buddhist art. Simple things like hand positions and the shape of the arms can convey symbolic meaning. Western viewers often have a hard time making sense of it all because they have little exposure to the symbols. Buddhist Flag. Each color and stripes has its own meanings. Blue : Universal Compassion. Yellow : The Middle Path.Red : Blessings. White : Purity and Liberation.Orange : Wisdom [Source: Myanmar Travel Information]

Scenes from the life of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, are a popular subject in Buddhist art. According to tradition, Siddhartha ("he who achieves his goal"), the founder of Buddhism, was born a prince of the Shakya clan in 563 B.C. in what is now southern Nepal. Confined by his father to the palace grounds he didn't visit the outside world at the age of twenty-nine. Moved by the suffering he saw, he abandoned his luxurious existence for a life of ascetic practice and sought to understand why the world was filled with physical decay, sickness, and death. He spent six years as an ascetic. Near death from excessive fasting, he was offered a bowl of rice from a young girl. After accepting it, he meditated beneath a pipal tree and reached enlightenment in one night. That tree became known as the "enlightenment" (bodhi) tree. He then set about teaching others what he had learned. Traditional accounts say that he died at the age of eighty, in 483 B.C.

Visual Buddhist art also includes manuscript making, calligraphy, block printing, and illumination, or book illustration. In China, Buddhist calligraphy was influenced by local traditions and Buddhist monasteries developed libraries for beautifully illustrated Buddhist texts.[Source: Encyclopedia.com]

See Separate Articles BUDDHIST SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART SUBJECTS, SYMBOLS, POSITIONS AND MUDRAS factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHIST ART factsanddetails.com ; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART IN ASIA FROM COUNTRY TO COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Art: Buddhist Symbols viewonbuddhism.org/general_symbols_buddhism ; Wikipedia article on Buddhist Art Wikipedia ; Asian Art at the British Museum britishmuseum.org; Buddhism and Buddhist Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Buddhist Art Huntington Archives Buddhist Art dsal.uchicago.edu/huntington ; Buddhist Art Resources academicinfo.net/buddhismart ; Buddhist Art, Smithsonian freersackler.si.edu ; Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“How to Read Buddhist Art” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art - How to Read)

by Kurt A. Behrendt Amazon.com ;

“Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols” by Meher McArthur Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art: An Historical and Cultural Journey” by Giles Beguin Amazon.com ;

“Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India” by John Guy Amazon.com ;

“Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com;

“Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art” by Adriana Proser, Susan Beningson Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art and Architecture” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Architecture” by Le Huu Phuoc Amazon.com ;

“The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road”

by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al.

Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road”

by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com;

“The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon” by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com

Buddhist Sculpture

There are more statues of Buddha in the world than of any one else. Some scholars claim that the idea of making Buddha statues was introduced to Asia from Europe. The earliest images of Buddha had Greco-Roman influences. In many of the early depictions, Buddha resembled Apollo.

Most of the really old art works found in Asia are Buddhist sculptures. More sculptures remain than paintings because more sculptures were probably made and paintings tend to deteriorate with time. Buddhist sculptures are generally made from wood or bronze. Some are gilt. Buddha images, whatever conditions they are in, are considered sacred. Climbing on them, and in some cultures, photographing them is considered disrespectful.

See Separate Article: BUDDHIST SCULPTURES: IMAGES, TYPES, BUDDHAS, DEITIES factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Painting and Artists

Tibetan Maitreya

Beginning in the third century caves in China, India and Southeast Asia were decorated with British frescoes a long with statues. Large monasteries sometimes contain hundreds and even thousands of frescoes and paintings of Buddha, Bodhisattvas and Buddhist gods such as Avalokitesvara. Many of the frescoes depict episode from Buddha's life and they are used to educate the illiterate masses the same way many Christian churches educate followers with scenes from the lives of Christ, Mary and the saints.

Paintings are often regarded as religious objects and sometimes used as meditation aids. Smithsonian Japanese art curator James Ulak wrote, "In every instance the artist attempted to create, through a single painting or an ensemble of paintings, an environment or moment of visual impact that complemented the faith of the viewer, enhanced a belief, and infused everyday life with a sense of transcendence."

Most works of Buddhist art have no signature or other identifying mark. Robert Beer, an artist and expert on Tibetan painting, told a Thai newspaper, “If you lose the need for individual expression, you’ll become more open to a tradition itself. So it’s more a process of evolving, and it’s very humbling in a sense because you lose your self importance of being a famous artist...so that everyone is essentially becoming part of the tradition itself, losing that need to become an artist, to understand, to be a personality.” Beer also said, “As you work on a drawing, you would think, “Why is she wearing this? Then through that you begin to understand Buddhist concepts because they are encapsulated in the images — why the deities have six arms, four arms, eight arms.”

See Separate Articles SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART ON THE SILK ROAD factsanddetails.com

Mandalas

Mandalas are important Buddhist artistic forms, particularly in Tibet. They are complex designs, comprising a circular border and one or more concentric circles enclosing a square divided into four triangles; in the centre of each triangle, and in the centre of the Mandala itself, are other circles containing images of divinities or their emblems.

Mandalas often serve as aids in meditation that symbolically depicts a world populated by bodhisattvas and other beings. They are typically painted on cloth scrolls but can also be depicted in three-dimensional form or made out of sand (to emphasize the impermanence of all things). These help guide people meditating visually from the outer world of appearance and illusion to the inner core of being, the very nature of the self and emptiness. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

During the initiation, the guru blindfolds the disciple and puts a flower in his hand; the disciple throws it into the Mandala, and the section into which it falls reveals the divinity who will be especially favourable to him.

See Separate Article: MANDALAS: TYPES, MEANING AND MAKING THEM factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Art in India

Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts from The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Early Buddhist art did not show the Buddha in human form. In relief sculptures at early stupa sites, his presence is indicated by symbols such as the lotus (signifying purity), the eight-spoked wheel (emblem of the Buddha’s law), the parasol (ancient symbol of royalty), and a footprint (the Buddha’s presence). [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York ]

Maitreya from India

It may be that this symbolic way of representing the Buddha arose from the view that with enlightenment he had transcended human form. Not until the first century A.D., more than five hundred years after his death, do images of the Buddha in human form begin to appear. Perhaps these figures were a response to emerging beliefs that the Buddha was not only a great spiritual teacher but also a savior god who, with personal devotion, could help others achieve nirvana.

“The earliest form of Buddhism is called the Theravada (Way of the Elders). It adheres strictly to the Buddha’s teaching and to his austere life of meditation and detachment. Theravada Buddhists believed that very few would reach nirvana. Initially, in this system, the Buddha was represented in art only by symbols, but in the first century A.D., under the Kushan rulers, the Buddha began to be depicted in human form. At about this time, a new form of Buddhism emerged called the Mahayana (the Great Way), which held that the Buddha was more than a great spiritual teacher but also a savior god.

“Another form of Buddhism, called Esoteric and also known as Tantric or Vajrayana Buddhism, grew out of Mahayana Buddhism beginning in the late sixth or early seventh century. Esoteric Buddhists accepted the tenets of the Mahayana but also used forms of meditation subtly directed by master teachers (gurus) involving magical words, symbols, and practices to speed the devotee toward enlightenment. They believed that those who practiced compassion and meditation with unwavering effort and acquired the wisdom to become detached from human passions could achieve in one lifetime a state of perfect bliss or “clear light,” their term for ultimate realization and release. Their practices paralleled concurrent developments in Hinduism.

“By the twelfth century, Buddhism was concentrated mainly in northeastern India, where the Buddha lived and preached. Its near extinction seems to have been caused by Muslim invaders who destroyed the Buddhist monastic universities. Teachers and monks fled to Nepal, Tibet, and Burma. Today only a small percentage of India’s population is Buddhist.

See Separate Article BUDDHIST ART IN INDIA factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Art in China

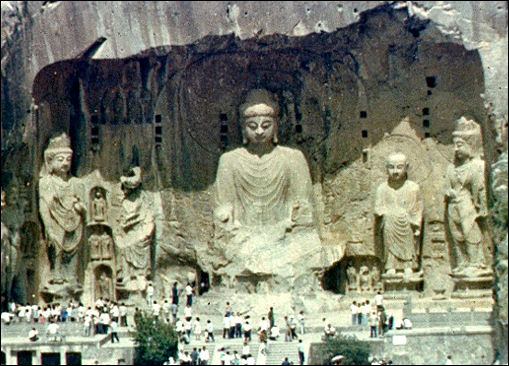

The most well known sculptures to come out of China are the images of Buddhas found in caves and sculptures unearthed from tombs. Art from India and Central Asia made its way into China in great amounts between the A.D. 1st and 5th centuries. During this period Buddhist art was created on the cave walls of Yungang.

As Buddhism, took root in China, it became a major cultural force, inspiring some of China's most brilliant paintings and sculptures. The periods of Chinese Buddhist art closely parallel the phases the Buddhist religion was going through in China . Works that appeared in the 5th and 6th centuries were very free and individualistic. In the Tang period the art became more mature and robust, with Buddhist figures featuring graceful lines and curves. In the 10th to 13th century it became more refined. After that it was rooted in tradition and lacked innovation.

Buddhists filled caves throughout China with sculptures and murals. In the cliffs of the Tian Shan mountains in the Kumtura and Kizil regions of Xinjiang province in western China, for example, there are hundreds of caves adorned with Buddhist painting that date as far back as the A.D. 5th century. Scholars believe the paintings — many depicting episodes from the lives of the Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, painted using paint made from ground minerals such as malachite for green and iron oxide for red — were commissioned by lay people and painted by local artists

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Buddhism brought to China a large range of divine beings, all of whom came to be depicted in images at temples, either on their walls or as free standing statues. The earliest Buddhist images in China owed much to traditions developed in Central Asia, but over time Chinese artists developed their own styles. Here we look separately at the evolution of the different divine beings in the Buddhist pantheon, then look briefly at groupings of deities.” [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

See Separate Article factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Cave Art in China

Chinese Tang-era Buddha

According to the Asia Society Museum: “The practice of excavating clusters of rooms or niches into the sides of cliffs and mountains to create cave temples originated in India and spread with Buddhism via Central Asia to China. Within China, Gansu is home to more Buddhist caves than any other region of Chinaóa testimony to its importance in the history of early Chinese Buddhism. “Dedication of Cave 4, Maijishan,” by the poet Yu Xin (513–581) reads: ‘It is as if one were to mount a carriage and pierce the mountain, carving out great niches, bestriding the peak, an infinite medley of stars overhead and all the land spinning around far below.’ [Source: “Monks and Merchants, curated by Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, November 17, 2001, Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org == ]

“Buddhist cave sites were often chosen for their scenic beauty, sometimes by passing monks who had seen Buddhist visions at a particular spot or were entranced by the spiritual aura of the sites. Cave temples were the focus of worship and meditation, not only for the communities of monks who resided there, but also for visiting pilgrims and traders. Indeed, cave temples were often located along the trade routes and were used by merchants as banks or warehouses. ==

“Buddhist images were arranged in the caves according to a strict iconographic program. At some sites the images were carved directly from the rock within the cave, but at many Buddhist cave sites in Gansu, the stone of the cliffs is too friable for carving. Instead, most images in the caves were crafted from mixture of clay and straw built up around armatures of wood or metal. A finishing layer of fine clay was applied in which the details were modeled. Both images and walls were brilliantly painted, but in many cases, the pigments have not survived. ==

See Separate Article BUDDHIST CAVE ART IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Art in Japan

12th century Buddhist painting The first inhabitants of Japan made pottery vessels and sculpture, but art that rose above the level of folk art wasn't really generated until Buddhism and Buddhist styles of painting, sculpture and architecture were introduced from Korea and China in the A.D. 6th century.

mandala maker The earliest forms of Buddhist art were paintings with a strong Indian influence and ornate mythical beast under the eaves of early Buddhist temples. Buddhism reached its zenith shortly after Nara, Japan's first capital, was established in A.D. 710. The city contained many magnificent temples and religious structures, including the colossal Todaiji Temples and the Daibatsu (Great Buddha Statue).

Daibutsusan in Nara is the world's largest bronze Buddha. Originally constructed between 735 and 749, the colossal sitting Buddha statue is 72 feet high, weighs over 550 tons and is covered with almost 300 pounds of gold.

Introduced to Japan from China during the Chinese Sung Dynasty (A.D. 960-1279), Zen Buddhism had a profound influence on Japanese art. Different from other Buddhist sects that preceded it and oriented more towards appreciation than worship, Zen eschewed art that was formalistic and ornamental and favored art that was disciplined, restrained, simple, and expressed inner feeling and harmony with nature.

Most of the really old art works found in Japan are Buddhist sculptures made for Buddhist temples. More sculptures remain than paintings because more sculptures wee probably made and paintings tend to deteriorate with time. Buddhist sculptures are generally made from wood or bronze. Some are gilded.. Many of the most outstanding works of Buddhist sculpture are made of wood.

See Separate Article EARLY JAPANESE ART AND BUDDHIST SCULPTURE: factsanddetails.com

Tibetan Buddhist Art

Tantric thangka Much of Tibetan art is oriented towards Buddha, gods and merit. Many works have complex iconography and symbolism that requires extensive knowledge about Tibetan Buddhism to unravel. Influences come from the Pala kingdom in India, the Newari kingdom in Nepal, Kashmir in India, Khotan in Xinjiang, and China.

Amitabha The major art forms are: 1) Tibetan paintings, including thangkas (cloth paintings), frescos, rock drawing and contemporary painting; 2) Tibetan sculptures, including Buddhist sculptures, metal sculptures, clay modelings and stone carvings; 3) Tibetan handicrafts, including metal wares, masks, block-printing, textiles handicrafts and wooden wares; and 4) Tibetan architectures including ancient tomb architecture, monastery architecture, palace architecture and residence architectures;

Most Tibetan art has traditionally been produced by monks at monasteries. Most artists were anonymous and rarely signed their works, although names have survived in texts, in murals on monastery walls, and on some thankas and bronzes. Mark Stevenson, a lecturer on Asian art at Melbourne University told the New York Times, “Every monk has a need for artistic talent. They make alms and assemble tormas, which are offering cakes. Many have to work on mandalas as well. This is part of being a monk. Every monk needs some manual dexterity skill in designing ritual objects.”

Much of Tibet’s great art was either destroyed by Communists, particularly in the Cultural Revolution, or taken out of Tibet and sold in art shops and auctions and now is in the hands of collectors. Tibetan are is increasingly being sought after by collectors. Art auctions sponsored by Christie’s and Sotheby’s often feature art that was looted or was confiscated during the Cultural Revolution.

See Separate Article TIBETAN ART AND PAINTINGS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN MANDALAS AND THANGKAS factsanddetails.com; TIBETAN SCULPTURE AND CRAFTS factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Art in Southeast Asia

Traditional Southeast Asian art is primarily composed of Buddhist art, which in turn often has Hindu elements and iconography in it. Traditional Southeast Asian sculpture almost exclusively depicts images of the Buddha. Traditional Thai paintings usually consist of book illustrations, and painted ornamentation of buildings such as palaces and temples. The above description is true for Thailand, Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos but less so for Vietnam, which has a stronger Chinese influence.

Khmer art mostly from present-day Cambodia is divided into three categories: 1) pre-Angkorian art from the 6th to 8th centuries, featuring Indian and Buddhist images and influences, and remarkably refined craftsmanship: 2) the high-Angkorian art from A.D. 802 to 1431, featuring Hindu and Buddhist stone, bronze and wood sculptures commissioned by the great Angkorian kings; and 3) the post-Angkor period, beginning after the sacking of Angkor by the Siamese in 1431.

In Khmer art, Buddha is often depicted meditating, seated on the coiled body of a serpent. His hands rest on his lap and multiple serpent heads spread in back of him. Standing Buddha convey different meanings through gestures and positions of the hand. Reclining Buddha lie on their right side with one hand folded under the head.

A number of Bodhisattvas are depicted. One of the most common is Avalokitesvara, “the god of compassion,” who is known in Cambodia as Lokesvara, “Lord of the World.” He is typically a small figure on the had of an image and carries a book, lotus and rosary in his four arms. Sometimes he has eight arms and hold various objects, The faces on the towers at Bayon are believed to be Avalokitesvara.

See Separate Article KHMER ART factsanddetails.com ART IN THAILAND: factsanddetails.com ; BURMESE ART: ANCIENT ART, CLASSICAL PAGAN ART AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com

Iconography and Meaning of Pagan Sculpture: The Enlightened Buddha

Dr. Richard M. Cooler wrote in “The Art and Culture of Burma”: “One of the peculiarities of Buddhist sculpture is that the most important event in the Buddha’s life from the point of view of mankind is not the event most frequently represented in sculpture. Depiction of the Buddha's personal enlightenment vastly outnumber representations of all other events in his life including that of his first sermon in which he shared his recently discovered knowledge with all humankind. The multiple images of the Buddha in Burmese art are excellent examples of this peculiarity in which the Buddha is most frequently shown seated with legs folded; left hand in his lap, palm upward; right hand on his shin, palm inward with fingers pointing toward the earth (bhumisparsa mudra). This hand gesture is symbolic of his overcoming the last obstacle to enlightenment, self-doubt. After years of asceticism and many days’ meditation under the Bodhi tree, the Buddha began to doubt that his past lives had been sufficiently perfect to warrant attaining enlightenment. This was because he believed in rebirth - a belief that the soul, like energy, cannot be created or destroyed, but instead experiences changes only from one form to another. [Source: “The Art and Culture of Burma,” Dr. Richard M. Cooler, Professor Emeritus Art History of Southeast Asia, Former Director, Center for Burma Studies =]

cave Buddha in China

“Therefore, the Buddha, like all mankind, had innumerable past lives, all of which would have had to have been lived to perfection if the Buddha was to achieve Nirvana. His difficulty lay in the fact that, like other mortals, he could not remember all his actions in all his former lives. Therefore, he could not be absolutely sure that enlightenment was eminent. By placing his hand on his shin and pointing towards the earth, he summoned the Earth Goddess to come to his assistance. Since in his former lives, the Buddha had participated in the common practice of pouring water on the ground to witness each of his meritorious acts, the Earth Goddess was able to wring a "tidal wave" of water from her hair that had accumulated over the Buddha's many previous lifetimes which was proof of his steadfastness and perfection. The Earth Goddess (Vasundari - Pali or Wathundaye - Burmese) is presented as a woman wringing water from the tresses of her hair, which constitutes one of the rare instances where women played an important role in the Buddha's life. This role, however, was not trivial. It was of pivotal importance because without her witness and assistance the Buddha would not have gained enlightenment. =

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Kalachakranet.org, onmarkproductions.com

Text Sources: “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “The Creators” by Daniel Boorstin National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024