BUDDHIST IMAGES

There are four main types of images found in Buddhist temples, each conveying a different level of being in Buddhist cosmology: 1) images of The Buddha; 2) images of Bodhisattvas; 3) images of deities, spirits, heavenly beings, and guardian god; and sometimes 4) images of kings of wisdom and light that serve as protectors of Buddhism.

For about five centuries after Buddha's death, it was forbidden to produce images of the Buddha. During that time various devices such as set of large footprints or a treelike post with three Dharma wheels were used to represent the Buddha without actually showing him. The Buddha and his early Disciples opposed the personalization of the Buddha’s message and discouraged speculation about their existence after they were dead. The Buddha hoped that his followers would find salvation though meditation, not through the worship of images. That didn’t stop millions of images of The Buddha and Bodhisattvas from being created though. If he were alive today The Buddha would no doubt be appalled by the number of images of him that have been raised around the globe.

Among the museums with great collections of Asian and Buddhist art are the Musee Guimet in Paris and the Museum for Indische Kunst in Berlin.

Buddhist Art: Buddhist Symbols viewonbuddhism.org/general_symbols_buddhism ; Wikipedia article on Buddhist Art Wikipedia ; Asian Art at the British Museum britishmuseum.org; Buddhism and Buddhist Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Buddhist Art Huntington Archives Buddhist Art dsal.uchicago.edu/huntington ; Buddhist Art Resources academicinfo.net/buddhismart ; Buddhist Art, Smithsonian freersackler.si.edu ; Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org

See Separate Articles BUDDHIST SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHIST ART factsanddetails.com; EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHIST ART factsanddetails.com ; SPREAD OF BUDDHISM AND BUDDHIST ART IN ASIA FROM COUNTRY TO COUNTRY factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“How to Read Buddhist Art” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art - How to Read)

by Kurt A. Behrendt Amazon.com ;

“Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols” by Meher McArthur Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art: An Historical and Cultural Journey” by Giles Beguin Amazon.com ;

“Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India” by John Guy Amazon.com ;

“Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com;

“Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art” by Adriana Proser, Susan Beningson Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art and Architecture” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Architecture” by Le Huu Phuoc Amazon.com ;

“The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road”

by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al.

Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road”

by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com;

“The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com;

“The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon” by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com

Buddha Images

Perhaps because the Buddha put so much emphasis on self-denial no images of him were made for some time after his death. When images were made they were not true likenesses. Instead they were highly stylized and symbolic with features like long era lobes, stretched by earrings, a sign of royal birth; wheel-shaped marks on the soles of his feet, reminders that his ministry had started the wheel of truth spinning.

Buddhist images are not idols. They do not represent any god and strictly-speaking are meant as a tool to help a person on the road to enlightenment. Even so they must be treated with great respect. In the old days people who desecrated the images or scraped the gold off them endured harsh punishments.

According to the Asia Society Museum: “Buddhist images are remarkably recognizable, regardless of their country or period of origin. They are usually made according to descriptions found in Indian texts intended to help the practitioner mentally invoke the form of the deity. These texts provide the artist with the basic schema of the image, detailing what an image should look like, from the posture, gesture, and color of the deity, to the attributes (objects he or she holds that symbolize specific powers or knowledge). Further similarities stem from the tendency of artists working elsewhere to emulate Indian models. Coming from the homeland of Shakyamuni Buddha and his teachings, such models held religious authority. The most prominent differences of period or culture of origin are usually seen in the images' details of costume, hairstyle, jewelry, body type, and facial characteristics. However, as is evidenced by the array of styles, artists working outside India did not simply copy Indian models-they created their own distinctive works. The artistic result of a religion that spread thousands of miles across a multiethnic landscape is a corpus of images based on a similar set of beliefs but marked by regional personalities. [Source:Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org ]

History of Buddha Images

Kushan-style Buddha

with vajrapani Mathura, AD 110 While it is difficult to imagine Buddhism without the Buddha image or Rupa, it was not until about 500 years after the passing away (Parinirvana) that the practice of making images of the Buddha started. Since that time, Buddha images have been the object of Buddhist devotion and identify for over 2000 years, acting as the inspirational focus and the means for devotees to express their reverence and gratitude for the Buddha's Dharma or Teachings. [Source: buddhanet.net +]

Technically, Buddha statues should not exist. They could be condemned as idolatry because the Buddha asked that no images be carved in his likeness. After his death devotees only paid tribute to representations of his identity — footprints, the chair he sat on, among other relics.“Eventually, the devotional impulse won out,’’ scholar Gary Gach told the Malaysian newspaper The Star.

Images of the Buddha have played as significant a role in Asian art as the image of Jesus Christ have in Western art. In early Indian depictions, the Buddha is often shown with a smile, symbolizing his enlightenment and inner peace. He is typically seated on a lotus throne with his hands in mudras, and his eyes are often closed. This style of portraying the Buddha originated in India and spread throughout Asia with the religion. In China, the Buddha was often depicted wearing golden robes with deep folds, and his facial features took on a more Chinese appearance over time. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The reasons for the Buddha images in shrine or temple are: 1) to remind one of the qualities of Perfect Wisdom and Perfect Compassion of the Buddha; 2) to inspire Buddhists to develop these qualities as we recall the greatness of the Buddha and His Teachings. According to Buddhanet.com: Some days, we may feel agitated, angry or depressed. When we pass by a shrine in our homes or visit a temple, and see the peaceful image of the Buddha, it helps us to remember that there are beings that are peaceful and we can become like them too. Automatically, our minds settle down.

Buddhist Sculptures

There are more statues of Buddha in the world than of any one else. Some scholars claim that the idea of making Buddha statues was introduced to Asia from Europe. The earliest images of Buddha had Greco-Roman influences. In many of the early depictions, Buddha resembled Apollo.

Most of the really old art works found in Asia are Buddhist sculptures. More sculptures remain than paintings because more sculptures were probably made and paintings tend to deteriorate with time. Buddhist sculptures are generally made from wood or bronze. Some are gilt. Buddha images, whatever conditions they are in, are considered sacred. Climbing on them, and in some cultures, photographing them is considered disrespectful.

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices;The very nature of a sculptural image in Buddhism is complex. Although there has been some debate about the matter, it is clear that Buddhists began to depict the Buddha early on, perhaps even before he died. The Buddha himself said that images of him would be permissible only if they were not worshiped. Rather, such images should provide an opportunity for reflection and meditation. Virtually all Buddhist temples and monasteries throughout the world contain sculptural images of the Buddha and the bodhisattvas. These images range from simple stone sculptures of the Buddha to incredibly intricate depictions of a bodhisattva like Kanon in Japan, with his thousand heads and elaborate hand gestures and iconographic details. And although these images function in the ritual context of the temple and monastery, they also serve an artistic and aesthetic purpose. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Giant Buddhas

Depictions of the Buddha often were made on a grand scale. In South Korea, at Sokkuram Grotto, the Buddha image was carved out of the face of a mountain. The giant Buddhas carved out of a cliff in Bamiyan, Afghanistan towered over Silk Road trade routes for centuries they were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

A giant Buddha created in Nara Japan in the eighth century is more than 15 meters (50 feet) high and weighs more than 200 tons. It was once was decorated with 500 pounds of gold. Sri Lanka is the home of a monumental Reclining Buddha sculpture. About 15 meters long, it was carved out of granite at the Gal Vihara Temple in Polonnaruwa.

Giant Buddha of Leshan in Sichuan China is a sitting Buddha carved into a cliff that overlooks the three rivers. A good example of a popular Asian saying, "the mountain is a Buddha, the Buddha is a mountain," it was conceived and started by a monk a monk named Hai Tong who wanted to build a statue to protect travelers at the confluence of Minjiang, Dadu and Qingyi Rivers, where it is situated. The giant Buddha is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

See Separate Articles: TODAIJI TEMPLE: WORLD'S LARGEST WOOD BUILDING AND ITS GREAT BUDDHA factsanddetails.com ; See Giant Buddha of Leshan Under SOUTH OF CHENGDU: MT. EMEI, DINOSAURS, THE GIANT BUDDHA factsanddetails.com and Giant Buddha Statues of Bamiyan under GANDHARA: ITS GREAT BUDDHIST ART AND TAXILA factsanddetails.com

Types of Buddha Images

Sakyamuni, the historical Buddha Traditionally, Buddhist artists have sought to depict one of 12 episodes of Buddha’s life: 1) his prior existence in Tusita Heaven; 2) his conception; 3) his birth 4) his education; 5) his marriage; 6) his renunciation; 7) his period of asceticism; 8) meditating under the Bodhi tree; 9) the defeat of Mara; 10) his enlightenment; 11) his first sermon; and 12) his death. Some of these episodes are depicted more often in paintings than in sculpture.

Statues Buddha is nearly always depict Buddha in one of half dozen or so position. The most common position shows a sitting Buddha with one hand raised (the sermon position). The second most common one shows The Buddha sitting with one hand on top of the other (the meditation position). The reclining Buddha symbolizes the sage in "an attitude of entering nirvana" and depicts The Buddha at the moment he leaves his earthly body and achieves the state of nirvana, or enlightenment. The standing Buddha is rare. He is thought to represents The Buddha as a teacher or perhaps giving a blessing.

Common Buddha images found in Japanese Buddhist temples include 1) Sakyamuni (the Historical Buddha), recognizable by one hand raised in a praying gesture; 2)Yakushi (the Healing Buddha), with one hand raised in the praying gesture and the other holding a vial of medicine; 3) Amitabha (The Buddha of Infinite Light and Buddha of the Western Paradise), sitting down with the knuckles together in a meditative position; 4) Dainichi (the Cosmic Buddha), usually portrayed in princely clothes, with one hand clasped around a raised a finger on the other hand (a sexual gesture indicating the unity of being); and Maitreya (Buddha of the Future).

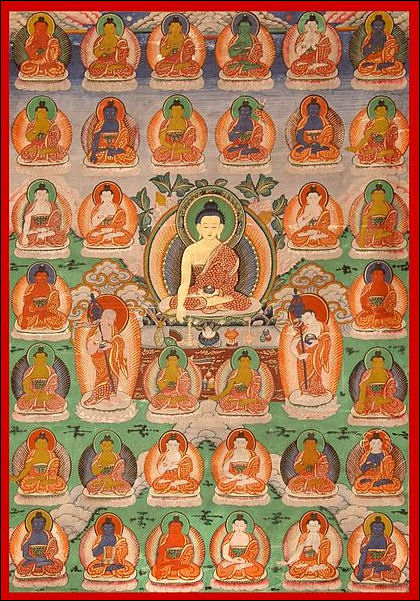

Buddhist art often contains a central image of Buddha surrounded by numerous other images, which can include scenes from Buddha life, different manifestations of Buddha, different Bodhisattvas and deities. Bodhisattvas often appear on either side of The Buddha. They are often distinguishable by their more human-like appearance; serene smiles which represent joy and compassion.; and a top knot of hair or a headpiece, sometimes with smaller figures in the crown. Some images of Buddha are accompanied by images of Buddha's first two disciples, young Ananda and old Kasyapa.

Present, Past and Future Buddha Images

Amitabha, The Buddha of Infinite Light Sakaymuni (Sakya Thukpa in Tibet) is the historical Buddha, who lived in Nepal in the 5th century B.C. He has blue hair and a halo of enlightenment around his head. He is always depicted in a sitting position, with his legs crossed in the lotus position and has 32 marks on his body, including a dot between his eyes, the Wheel of Law on the soles of his feet, and bump on the top of his head. Manifesting the “witness” mudra, he holds a begging bowl in his left hand and touches the earth with his right hand. He is often flanked by two bodhisattvas. [The name before the parenthesis is Sanskit, the name in parenthesis is Tibetan]

Dipamkara (Marmedze) is the Past Buddha. He preceded the historical Buddha and spent 100,000 years on earth. His hands are pictured in the “protection” mudra and he is often pictured with the Present and Future Buddha.

Maitreya (Jampa) is the Future Buddha. He is currently in the form of a bodhisattva and is waiting for his chance to return to earth, 4000 years after the death of Sakaymuni. He is usually seated, with a scarf around his waist, his legs hanging down and his hands by his chest in the turning of the Wheel of Law.

It said the Maitreya, the Future Buddha, will appear around 30,000 years from now. At present Maitreya is believed to reside in the Tutshita. heaven, awaiting his last rebirth when the time is ripe. His name is derived from mitra, 'friend.' Friendliness is a basic Buddhist virtue, somewhat like Christian love.

Other Tibetan Buddha Images

Amitabha (Amitabha Opagme in Tibet) is the Buddha of Infinite Light. He resides in the “pure land of the west,” where he looks after people on their journey to nirvana, and is regarded as the original being from which the Panchen Lama was reincarnated. He is red. His hands are held together on his lap with a begging bowl in the “meditation” mudra.

Dhyani Buddhas, or the five Contemplation Buddhas, are: Amitabha (red), Vairocana, Akshobhya (white), Ratnasambhava (yellow) and Amoghasiddhi (green) “are major focuses of meditation. Also known as the five Jinas (eminent ones), or dhyani-Buddha, they control the different regions of paradise where Buddhists may be reborn. Each is a different color and has different symbols and mudras associated with it.

Amitayus (Tsepame) is the Buddha of Longevity. Like Amitabha, he is red and his hands are pictured in the “meditation” mudra, but he holds a vase containing the nectar of immortality. The Medicine Buddha (Menlha) holds a medicine bowl in his left hand and herbs in his right hand. He is often depicted in a group of eight Buddhas.

These Buddhas have different manifestations. The many-headed Hevajra is a wrathful manifestation of Akshobhya (the Imperturbable Buddha). Symbolizing the transformation of the poisons such as anger, he is often depicted in an embrace with his consort Nairatmya. Their passionate embrace represents the enlightened state that come from the union of wisdom and compassion. Hevajra is often shown stomping his own image, showing the defeat of egoism.

Avalokitesvara

Avalokitesvara (meaning “Lord Who Looks Down”) is arguably the most common and popular Buddhist celestial being. Regarded as a god, a goddess and a Bodhisattva and featured prominently in the Lotus Sutra, he is closely associated with Amitabha and lives between births in Amitabha’s Western paradise.

Avalokitesvara has a number of body parts and objects with symbolic meaning. Of his 11 heads, the central head one at the top belongs to Amitabha. He often has multiple arms, sometimes more than a thousand of them. The central pair of hands is in the cupped position representing respect. In one hand he hold a lotus, symbolizing enlightenment, In another he holds a bow and arrow, symbolizing a Bodhisattva’s ability to get at the heart of the matter.

Avalokitesvara appears in 33 different manifestations and 108 forms, including the goddess of mercy, popular with pregnant mothers and invoked by people in trouble. Simply repeating her name several times is considered enough to drive away evil.

A nearly life-sized bronze image of a four-armed Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara from the 9th century is the largest figure in a hoard of sculptures found buried at a site in Buriram Province, Prakhon Chai in what is now northern Thailand. The find contained both Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhist deities. Who made the images and why they were buried is still a mystery. The form of the torso, the rather square face, the eyes, lips, and mustache of this figure resemble late seventh- and eighth-century Cambodian sculpture. Avalokiteshvara’s identifying feature is a small figure of a seated Buddha in his elaborate hair arrangement and headdress. Originally some of his hands may have held separately cast attributes. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

The figure’s meditative gaze and serene expression contrast with the sense of energy generated by the active gestures of the fingers and by the subtle weight shift of his wiry body onto the right leg, suggesting potential movement. The smooth surfaces are almost devoid of decoration except for the fine patterns of the hair and headdress and the delicate details of the sampot folds and sashes. The bronze contains a large amount of tin, giving the surface a silvery sheen. The pupils of the eyes probably originally were inlaid with glass paste.

Tibetan Buddhist Bodhisattva Images

Avalokitesvara Jampelyang (Manjushri) is the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. He is regarded as the first divine teacher of Buddhist thought and is sort of a patron saint for school children. In his right hand is a flaming sword that cuts ignorance. His left, in the “teaching” mudra, cradles a half-opened lotus blossom. He is often yellow and has blue hair or a crown.

Drolma (Tara) is a female bodhisattva with 21 different manifestations. Known as the saviouress, she was born from a tear of compassion shed by Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara)and considered a female version of Chenresig and a protectress of the Tibetan people. She symbolizes purity and fertility and is believed to be able to fulfill wishes.

Drolma is often picturesdin a longevity triad with the red Tsepame (Amitayus) and the three-faced, eight-armed female Namgyelma (Vijaya). In her green manifestation Drolma sits in a half lotus position on a lotus flower. In her white manifestation she sits in a the full lotus position and has seven eyes, including ones on her forehead, both palms, and both soles of her feet.

Tibetan Protector Deities

Guardian King Dhritarastra Chokyoing (Lokpalas) are the Four Guardian Kings. Often found at the entrance hallway of monasteries and believed to be Mongolian in origin, they protect the four cardinal directions. The eastern king is white and carries a lute. The southern king is blue and carries a sword. The western king is red and carries a thunderbolt. The northern king is yellow and carries a banner of victory and a jewel-spitting mongoose. He is regarded as the god of wealth and is depicted riding a snow lion.

Yamantaka, conqueror of death Dorje Jigje (Yamantaka) is the most well-known protector of the Yellow Hat sect. Known as the destroyer of Yama, the Lord of Death, he is a blue, beastly-looking creature with eight heads, one of which is the head of a bull, and strings of skulls around his waist and neck. He holds a flaying knife and a skull cup in his eight to 36 arms. With his 16 feet he stomps on eight Hindu gods, eight mammals and eight birds. Dorje Jigje punishes evil people to a life in hell, helps guide good people to a better rebirth and crushes earthly passions that block enlightenment. Yamanataka is so horrible that no one should look at his image, especially women. Statues of him are often covered.

Yamantaka Nagpo Chenpo (Mahakala) is wrathful Tantric god and a manifestation of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara). Associated with the Hindu god Shiva, he is blue and has fanged teeth, a crown fo skulls, and carries a trident and skull cup. He comes in various forms, with two to six arms and is regarded as the protector of tents by nomads. Nangpo Chenpo means the Great Black One .

Tamdrin (Hahagriva) is another wrathful manifestation of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara). Associated with the Hindu god Vishnu, he is red with a white face on the right and green gace on the left and has a horse’s head in his hair, a crown of skulls, a tiger skin around his waist and a garland of 52 chopped off heads. On his back are the wings of Garuda. In his six hands are a lotus, club sword, skull cup, snare and ax. Under his four legs a sun disc and corpses. Tandrin in red and Dorje in blue often serve as guardian gods at the entrance of temples.

Mahakala Chan Dorje (Vajrapani) is the wrathful Bodhisattva of Energy. He is blue with a tiger skin around his waist and snake around his neck. In his right hand is a thunderbolt, the symbol of the Tantric faith. Chan Dorje means “thunderbolt in hand.”

Demchok (Chakrasamvara) is a meditational deity with a blue body, 12 arms, four faces, and a crescent moon in his topnot. In his hands are a thunderbolt, a bell, a elephant skin, an axe, a hooked knife, a trident, a skull, a hand drum, a skull cup, a lasso and head of Brahma. He wears a tiger skin and has a garland with 52 severed heads around his neck.

Palden Lhamo (Shri devi) is the guardian of Lhasa, the Dalai Lama an the Yellow Hat sect. An angry manifestation of Tara The female counterpart of Nagpo Chenpo (Mahakala), she is blue, wears tiger skin and human skin clothes and has earrings made of a snake and a lion and carries a skull cup full of blood in her left hand and a club in her right hand. A moon is in her hair; the sun is her stomach; and a corpse is in her mouth.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Kalachakranet.org and Simha.com

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024