TODAIJI TEMPLE

Todaiji

Todaiji Temple was built in 741 to be the central temple of all provincial temples established in Japan. Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998, and restored in the mid-1990s, it embraces several buildings and is the main temple of the Kegonshu sect of Buddhism. It was built under Emperor Shomu (701-756) in hopes of keeping Japan peaceful so he could devote himself to Buddhism, and rebuilt in 1692 and 1709.

The original main temple is said to have been even more spectacular than the one that exists now. The original was 86 meters wide, 29 meters wider than the current building, and the Buddha was covered in gold. Built in the style of a Chinese palace building, the main hall had enormous red columns along with a yellow ceiling, green window frames, white walls and a black tile roof. Two 90-meter-tall, seven-story pagodas stood at opposite ends of the from hall. Both were later destroyed.

Daibutsuden (within Todaiji Temple) is the world’s largest wooden structure. Built to house the world’s largest Buddha, it is a masterpiece of wooden architecture. Many of the criss-crossing beams are positioned without nails. In addition to the Buddha there are towering 30-foot-high wooden statues of warriors and gods. One large wooden pillar contains a small hole large enough for some people to crawl through and is about the size of one of the Great Buddha’s nostrils. The pillar shows that the structure is imperfect and has room for improvement. It is said that those who crawl though it will receive enlightenment and have all their prayers answered. Nearby is Kaidan-in Hall, which was once used for ordination ceremonies and contains clay images of the Four Heavenly Guardians; Sangatsu-do-Hall, the oldest building in the Todaiji Temple complex; and Nigatsu-do Hall. The two stone lions at the temples south gate are believed to have been made in China.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Nara Buddhist Art, Todai-Ji: 5 (Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art) by Takeshi Kobayashi Amazon.com; “Todai-Ji” (1964) by Taikichi - photographed by Irie Amazon.com; “A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism” by William E. Deal, Brian Rupper Amazon.com; “Nara: A Cultural Guide to Japan's Ancient Capital” by John H. Martin and Phyllis G. Martin Amazon.com; “Nara Japan, 749-757: A Translation from Shoku Nihongi” by Ross Bender Amazon.com; Envisioning Heijokyo: 100 Questions & Answers about the Ancient Capital in Nara, Japan by Yoko Hsueh Shirai Amazon.com; “The Last Female Emperor of Nara Japan, 749-770" by Ross Bender Amazon.com; “Life In Ancient Japan” by Hazel Richardson Amazon.com; “Daily Life and Demographics in Ancient Japan” (Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies) (2009) by William W Farris Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan” (Volume 1) by Delmer M. Brown Amazon.com

History of Todaiji Temple and the Great Buddha

Todaiji guardian According to Kanshu Tsutsui, the chief administrator of Todaji, to build such a large statue and buildings, workers had to dig down 2.5 meters over a 90 meters by 60 meter area — larger than a football field — to find firm ground. The concrete-like layers of clay, ballast and sand placed on the firm ground were similar that layers below the Great Wall of China. “It was built using architectural styles of ancient Chinese palace buildings,” Katsuaki Ohashi, a professor specializing in East Asian arts at Waseda University, told the Yomiuri Shimbun. “In China, the style was applied to building Buddhist temples when Buddhism entered the country from India, and it was later imported to Japan via the Korean Peninsula.” [Source: Shinichi Yanagawa, Daily Yomiuri, January 7, 2010]

After completing the 2.5-meter-high platform craftsmen made a mold to cast the Buddha statue. After the casting was done then the columns were raised for the building. The platform as well was the statue from the knees down are filled with sand. These parts survived the fire that brought down the original buildings. Katsuaki Ohashi, a professor specializing in East Asian arts at Waseda University, said, “I believe construction technologies here had already surpassed those of China at that point.”

Kawagoe wrote: In his organization of the country, Emperor Shomu applied the principle of the mandala. A mandala was a geometrical figure in which shapes and colours were arranged as a symbolic matrix of the universe. The Todai-ji that was dedicated to the Buddha Vairocana in the centre of a lotus flower with a thousand petals and symbolized the universe. Millions of copies of sutra and wood engravings of religious images were made for distribution to the pilgrims who thronged the temple. These were the first printed documents in Japan. [Source: Heritage Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

Shinichi Yanagawa wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The name Todaiji literally means giant temple east of the capital. It served as an institute of higher learning for monks and as the headquarters of Kokubunji temples established by Emperor Shomu across the nation to propagate Buddhist teachings. He dispatched to the temples monks with knowledge in medicine, civil engineering, arts and other fields.“Emperor Shomu intended to raise cultural standards in rural regions with the culture of the capital,” Tsutsui said. “The monks instructed people to build reservoirs as a countermeasure against famine and to repair roads and rice fields. The monks also taught people how to build comfortable houses and which medicines to take. “The temples were bases for carrying out such community projects. Building the Great Buddha was a project to help people understand the importance of cooperation in building a better society,” Tsutsui said. “Some people say the Great Buddha was constructed to show foreign countries the power of the nation, but it was not that simple.”

Daibutsusan (Great Buddha of Nara)

Daibutsusan, the world's largest bronze Buddha Daibutsu (within Daibutsuden) is the world’s largest bronze Buddha by some reckonings. Originally constructed between 735 and 749, the colossal sitting Buddha statue is 72 feet high, weighs over 550 tons and is covered with almost 300 pounds of gold. Housed in the Great Buddha Hall, the Nara Buddha (also called Daibutsu in Japanese), it is surrounded by a halo from which three hundred gold statues were hung. The image took two years to cast and three more to polish and cover in gold leaves.

The Buddha is a representation of the Cosmic Buddha, who gives rise to new worlds. Buddhists believe the statue emits divine light to the far corners of the universe and each lotus leaf it sits upon represents a separate universe. The Buddha is believed to have been built to pray for peace and bring relief to a people who had suffered years of drought, famine, political violence, earthquakes and smallpox. It was also intended, some say, to show off the power of Emperor Shomu, who is said to have wanted a Buddha large enough to bring good fortune to everyone. The Great Buddha was completed three years after his death.

The statue’s sullen facial expression may have something to with the fact it lost its head in an earthquake in 9th century and suffered damage from civil wars in the 16th century. In 1180 and again in 1567, its right hand was melted in accidental fires. The body of the statue was reconstructed in 1185, and the head rebuilt in 1692. The present statue is only two thirds the size of the original.

Daibutsu is the largest bronze image (at 14.98 meters, 49.1 feet) from the ancient world and the largest single-caste bronze image. There are larger bronze Buddhas in the world. The Ushiku, a 110 meters modern-day bronze Buddha, was completed in 1995 in Ibaraki prefecture, Japan. The Spring Temple Buddha in China is 128 meters tall. [Source: Heritage Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

During the annual cleaning event in August the giant Buddha statue is dusted by monks sitting on chairs suspended by ropes from the ceiling. The cleaning takes 2½ hours and is conducted by 210 monks, who wear white uniforms and begin their work after a ceremony to remove the statue’s soul to avoid any impurity to Buddha’s image.

Construction of the Daibutsu (Great Buddha of Nara)

According to Todaji records 2.6 million people were employed to construct the original Daibutsuden wood building and more than half million worked on gold plating the bronze statue, which took five years. About 500 tons of copper and 8.5 tons of tin was used to cast the original Buddha and 440 kilograms of gold and 2.5 tons of mercury were used to plate the statue using a technique in which the gold was mixed with mercury at a ratio of 1 to 5 and placed on the statue and heated so the mercury evaporated away leaving the gold. The work was done relatively quickly so the construction could be completed in time for the 200th anniversary of the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in 752.

Kawagoe wrote: In 743, Emperor Shomu on an imperial visit to Shigaraki Palace in Omi Province proclaimed that he wanted a colossal image of Vairocana (Biru-shana butsu in Japanese) Buddha to be cast. Work began immediately in Omi Province, but was suspended in 745 when the emperor returned to Nara. The work was recommenced in 747 at Nara’s Todaiji Temple which had already been designated one of the provincial temples of Yamato Province. [Source: Heritage Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

“The idea for the construction of the Nara Buddha is said to have begun with Emperor Shomu and his empress Komyo, in consultation with the great monk Gioki. Gioki traveled through much of Japan bearing the proclamation of the Emperor announcing the project of the Great Buddha of Nara and inviting the contribution of all, “It is our desire that each peasant shall have the right to add his handful of clay and his strip of grass to the mighty figure.” The project thus embodied not only imperial and aristocratic patronage but also the labours of even the humblest peasant.

“The Great Buddha project utilized... 499 tonnes of bronze and 440 kilogrammes of gold. It was said that it had used up all the country’s reserves of bronze and precious metals. Artists had come from all over Asia, particularly from India and China, to help create the 16 meter (52 feet) high bronze statue. The Great Buddha required 8 castings over a period of 3 years. The Emperor is said to have assisted the erection work with his whole court, and ladies of the highest rank are said to have carried clay for the model on their brocaded sleeves. The project finally completed in 749, an official “eye-opening” consecration ceremony of unprecedented splendour was held to showcase the Great Buddha in 752.

Why Did Emperor Shomu Build the Great Buddha of Nara

Emperor Shomu

Why did Emperor Shomu have the Great Buddha built? Kansho Tsutsui, the administration chief of Todaiji temple in Nara, told the Yomiuri Shimbun Emperor Shomu had Todaiji temple and the Great Buddha constructed to pray for the nation’s peace and to bring relief to the people because of years of drought, famine, political strife, earthquakes and smallpox. “Emperor Shomu hoped that people would realize their connection with nature and the universe,” Tsutsui said, adding, “The giant statue was a symbol for that purpose.”

Kosei Morimoto, an abbot at Todaiji told the Yomiuri Shimbun: “There’s a document that says the decision was reached by the emperor in 734 after he'd been worrying greatly about his leadership. Around that time, many people had starved to death after a series of natural disasters, including drought, famine and a major earthquake. People stole from one another to survive.”

“The emperor had studied Confucianism and Chinese history books for ideas about administering the affairs of state, and in this time of trouble he decided to shift his administration’s basic philosophy from Confucianism to Buddhism,” Morimoto said. “According to Confucianism, natural disasters occur to punish poor rulers. That idea tortured the sincere emperor. There had also been two smallpox epidemics, which killed four brothers of Empress Komyo along with high-ranking officials and many commoners. It’s said tens of thousands of people died from the disease. The capital became desolate.”

Morimoto said: “The emperor also blamed himself for the increase in crimes committed by commoners, and he had provincial temples and convents established across the nation to save those people’s souls. The principal image of the temples outside the capital was Shakamuni [an incarnation of Buddha], but for Todaiji, the capital’s temple, he decided to have the Great Buddha built as the principal image.” The empress established facilities to accommodate impoverished people, the sick and orphans. She was very concerned about people’s welfare.

Kawagoe wrote: Although the great many state and provincial temples had been built for the hope of gaining peace and prosperity for the state and its subjects, the Great Buddha project was different in one important respect. Temples were always built for the purpose of securing the temporary healing or happiness and eternal salvation of the imperial family or of members of notable clan members such as the Fujiwara and Tachibana clans. In constructing the Great Buddha, no mention was made of the material or spiritual welfare of the great aristocratic families – what was emphasized was the fruit of cooperation on the part of all devout Buddhists. [Source: Heritage Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com ]

“Through the merits accruing from the good work and contribution of believers, all believers would receive the same blessings as the emperor himself and would attain the same state of enlightenment. Vairocana is the principal buddha of the Kegon-kyo (Flower Garland Sutra), a text that describes the Vairocana Buddha as the great light that governs all things and that dwells in the Pure Land of the Lotus Womb. The Nara Buddha was a cosmic Buddha that was central to the order of the universe.

“In this project, hence, were the seeds – the beginnings of Buddhist universalism – that would continue to be developed in the Heian period that was to follow. Many provincial temples would cease to function and fall into ruin by the middle of the 10th century, but Todaiji and the Great Buddha would survive over the centuries — their survival perhaps in part due to the Great Buddha’s universal appeal that would remain entrenched in the consciousness of the people.”

Ceremony to Consecrate the Great Buddha of Nara

In 752, a magnificent ceremony was held to consecrate the new Buddha statue. The gold plating was completed only 53 days before the ceremony. At the consecration ceremony, Korean, Southeast Asian and Chinese dances were performed and an India monk who lived in Tang-era China brushed ink into the Buddha’s eyes. “Since [Tenpyo era] people strongly aspired to the culture of Changan, the dynasty’s capital, I think they wanted people from there to come to the ceremony,” Katsuaki Ohashi, a professor specializing in East Asian arts at Waseda University, told the Daily Yomiuri.

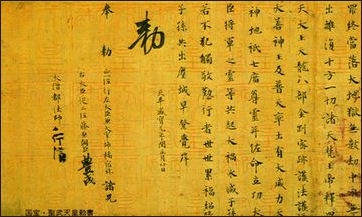

Shomu rescript

Shinichi Yanagawa wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The consecration ceremony was attended by 10,000 people, including Retired Emperor Shomu, Retired Empress Komyo and their daughter Empress-regnant Koken. Buddhist instruments used in the ceremony are included in the treasures of the Shoso-in repository. It had an international flavor due to cultural exchanges with other Buddhist Asian countries. An Indian monk, who had lived at Daianji temple after moving to Tang-dynasty China and finally came to Japan, brushed ink into the Buddha’s eyes. Folk dances of China, the Korean Peninsula and Indochina were presented on a special stage. Jianzhen, one of China’s highest ranking monks, who was better known as Ganjin in Japan, was to be invited to the ceremony, but he could not arrive in time due to the difficulty of the voyage and for other reasons. [Source: Shinichi Yanagawa, Daily Yomiuri, January 7, 2010]

Kawagoe wrote: “An official “eye-opening” consecration ceremony of unprecedented splendour was held to showcase the Great Buddha in 752. It was attended by...all major court officials, civil and military. Thousands of monks came from all corners of Japan and the rest of Asia together with members of the court, foreign ambassadors, and army officers...The monk Gioki lived only just long enough to see his great life-work completed, dying the day after the inauguration ceremony.” [Source: Heritage Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

Morimoto told the Daily Yomiuri: “It is said Bodai Senna, the Indian priest who led the ceremony, took a brush and black ink and drew pupils on the Buddha’s eyes to give the statue life. The brush was tied to the silk cord, which the emperor, empress and other participants held so they could share in the joy of the event. The cord was about 200 meters long.”

A concert was held at the ceremony. Various Japanese and foreign songs were sung. A gigaku play was also performed. Gigaku is a form of comical, silent drama where the actors wear different masks, and there’s musical accompaniment from percussion and flute. A 7th century gigaku mask in the Shoso-in collection depicts a ruddy-faced foreign king who lead a group of drunken men. It’s high bridged- nose and other strong features have led some to speculate the king was supposed to be a Persian. Gigaku is thought to have originated in the Wu kingdom of ancient China and was introduced to Japan by the Paekche kingdom on the Korean peninsula.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Ray Kinnane

Text Sources: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com; Charles T. Keally, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology (retired), Sophia University, Tokyo ++; Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org ~; Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan; Library of Congress; Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO); New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; Daily Yomiuri; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated January 2024