EARLIEST EVIDENCE OF MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA

86,000–68,000 year old bones from Tam Pà Ling, Northern Laos a) Medial view indicating the inferior portion of the tibial tuberosity; b) left lateral view indicating the interosseous crest; c) posterior view indicating the vertical line; d) anterior view; e) distal view; f) proximal view

The first modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) arrived in Southeast Asia as early as 90,000 years ago. The earliest evidence of modern humans in Southeast Asia comes from Tam Pa Ling Cave in the Annamite Mountains in northern Laos. According to Archaeology magazine Luminescence dating of sediments there that contain human bones indicates that Homo sapiens arrived in Southeast Asia between 86,000 and 68,000 years ago, tens of thousands of years earlier than previously thought. The new research also suggests that people traveled not only along coastal routes and seaways but along inland river valleys as well. In 2009 a skull recovered from Tam Pa Ling Cave was dated at least 46,000 years old, making it the oldest modern human fossil found to date in Southeast Asia. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2023, Wikipedia]

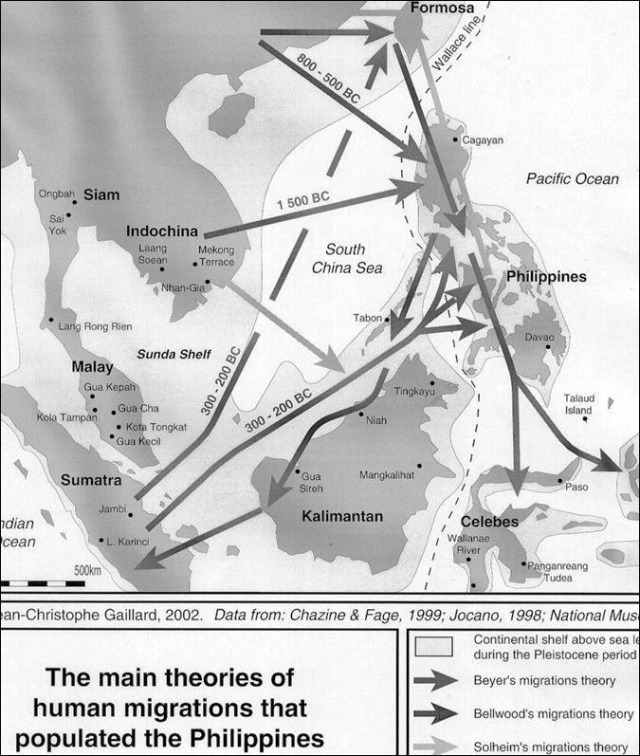

The earliest evidence of modern humans in Indonesia —63,000-73,000 years before present — is Lida Ajer cave in Sumatra. Teeth were found there in the 19th century. The earliest evidence of modern humans in Philippines —67,000 years before present — is Callao Cave. Archaeologists, Dr. Armand Mijares with Dr. Phil Piper found bones in a cave near Peñablanca, Cagayan in 2010 that were dated to be 67,000 years old. It's the earliest human fossil ever found in Asia-Pacific.

The oldest human settlement in Malaysia has been discovered in Niah Caves in Borneo. The human remains found there have been dated back to 40,000 to 65,000 years ago. Stone artifacts dating to 40,000 years ago have been found at Tham Lod Rockshelter in Mae Hong Son in Thailand. Archaeological evidence of Homo sapiens from central Myanmar has been dated to about 25,000 before the present. [Source: Wikipedia]

The first human migrations out of Africa are thought to have taken place over 100,000 years ago. They likely crossed India to reach Southeast Asia. According to PBS: “Migrants gradually made their way down India's coast over a few thousand years. The migration was possible because sea levels were 200 feet lower then they are now, allowing travel via long-since submerged land bridges. The migrants' descendants have been identified by DNA markers as far north as the Pakistani coast and as far south as the Kallar tribe on the Kerala coast in modern India, where entire villages share ancient DNA strains. Along India's west coast there remain pockets of tribal peoples who may have descended from these first human migrations. Until the modern age they have remained largely self-contained, endogamous (marrying within the tribe), physically distinctive in appearance and outside the Hindu caste system. Many retain their own languages, which are distinct from the main Northern and Southern Indian language groups. [Source: PBS, The Story of India, pbs.org/thestoryofindia]

RELATED ARTICLES:

FIRST HOMININS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

HOMO FLORESIENSIS: HOBBITS OF INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

ORIGINS AND ANCESTORS OF HOMO FLORESIENSIS (HOBBITS) factsanddetails.com

DENISOVANS: CHARACTERISTICS, DISCOVERY AND DNA factsanddetails.com

WHERE DENISOVANS LIVED: MOSTLY IN ASIA IT SEEMS factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLIEST MODERN HUMANS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMANS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

LIFESTYLE OF EARLY HUMANS IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

DNA EVIDENCE ON THE FIRST HUMANS IN EAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Forgotten Exodus: The Into Africa Theory of Human Evolution” by Bruce Fenton (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Real Eve: Modern Man's Journey Out of Africa” by Stephen Oppenheimer (2004) Amazon.com;

“Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond” (Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology) by Christopher J. Norton and David R. Braun Amazon.com;

“Emergence and Diversity of Modern Human Behavior in Paleolithic Asia” by Yousuke Kaifu, Masami Izuho, et al. Amazon.com;

“Paleoanthropology and Paleolithic Archaeology in the People's Republic of China” by Wu Rukang, John W Olsen Amazon.com;

“In search of Homo erectus: a Prehistoric Investigation: The humans who lived two million years before the Neanderthals” by Christopher Seddon (2017) Amazon.com;

“Peking Man” Amazon.com;

“Java Man : How Two Geologists' Dramatic Discoveries Changed Our Understanding of the Evolutionary Path to Modern Humans” by Roger Lewin , Garniss H. Curtis, et al. Amazon.com;

“Little Species, Big Mystery: The Story of Homo Floresiensis” by Debbie Argue Amazon.com;

“Homo Floresiensis: Diving Deep into our Evolutionary Past” by Austin Mardon, Catherine Mardon, et al. Amazon.com;

“A New Human: The Startling Discovery and Strange Story of the "Hobbits" of Flores, Indonesia” by Mike Morwood, Penny van Oosterzee (2007) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013) Amazon.com;

Early Modern Man Migrates to Asia

The fact that some of earliest evidence of modern humans outside of Africa and the Middle East is in Australia suggests that the early man followed a coastal route through South Asia and Southeast Asia to Australia. It is believed that the migration was not a caravan-like journey but rather one in which some huts were set up on the beach and the migrants lived there for a while moving and then moved to a new location further to the east every couple of years. Traces of such a migration if it took place were covered in water and sediments when sea levels rose at the end of the Ice Age.

Around 40,000 years ago, it is thought, humans reached the steppes of Central Asia and pushed on into Siberia. There is evidence of human habitation on the northern Yana River in Siberia dated to 30,000 years ago.

Some genetic evidence indicates that a group of 4,000 modern humans left Africa between 75,000 and 50,000 years ago and ultimately populated Asia. All non-Africans share genetic markers (the M168 marker in particular) carried by these early immigrants. The descendants of these people replaced all earlier types of humans, notably Neanderthals. All-non Africans are descendants of these people. The Onge from the Andaman Islands in India carry some of the oldest genetic markers found outside Africa.

Many scientists believe the migration took place rather late and humans that took part in it spread very far, very quickly, This theory is backed in part by the features of skulls of ancient modern men found in Europe, Asia and even Australia with those of the Hofmeyr skull found in South Africa in the 195's and dated to be 33,000 to 42,000 years old. This finding was reported in a January 2007 article in the journal Science by team led by Frederick Grine at State University of New York at Stony Brook.

The dating of the Hofmeyer skull has provided an important piece of the puzzle. Before it was dated no human fossil existed for the period between 15,000 and 70,000 years ago when the great migration out of Africa was taking place. The skull was dated by Richard Baily at Oxford University using a new technology that measures the amounts of radiation absorbed by sand grains that filled its braincase after burial. When the skull was found this technology did not exist and it was originally thought to be undatable because no other bones were found near it and its original resting place had been disrupted by river sediments.

See Separate Articles: EARLY MODERN HUMANS MIGRATE TO ASIA factsanddetails.com

North-South Genetic Divide Among Native Populations in East Asia

Chinese researchers Feng Zhang, Bing Su, Ya-ping Zhang and Li Jin wrote in an article published by the Royal Society: In recent years researchers in China have made substantial efforts to collect samples and generate data especially for markers on Y chromosomes and mtDNA. The hallmark of these efforts is the discovery and confirmation of consistent distinction between northern and southern East Asian populations at genetic markers across the genome. With the confirmation of an African origin for East Asian populations and the observation of a dominating impact of the gene flow entering East Asia from the south in early human settlement, interpretation of the north–south division in this context poses the challenge to the field. Other areas of interest that have been studied include the gene flow between East Asia and its neighbouring regions (i.e. Central Asia, the Sub-continent, America and the Pacific Islands), the origin of Sino-Tibetan populations and expansion of the Chinese. [Source: “Genetic studies of human diversity in East Asia” by 1) Feng Zhang, Institute of Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University, 2) Bing Su, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, 3) Ya-ping Zhang, Laboratory for Conservation and Utilization of Bio-resource, Yunnan University and 4) Li Jin, Institute of Genetics, School of Life Sciences, Fudan University. Author for correspondence (ljin007@gmail.com), 2007 The Royal Society, [Source: Genetic studies of human diversity in East Asia ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

***]Genetic markers are the tools in studying genetic variations. The most important genetic markers in human genetic diversity research (Du 2004) are: (I) blood groups that can be detected in red blood cells, including ABO, Rh and MNSs, (ii) human lymphocyte antigens and immunoglobulins, including Gm, Km and Am, (iii) isozyme markers, (iv) classic DNA polymorphisms using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), and (v) contemporary DNA markers, including short tandem repeat (STR or microsatellite) and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). However, it is the introduction of mtDNA and Y chromosome markers that has made a profound impact on our understanding of the genetic diversity of human populations . ***

Zhao et al. (1987) and Zhao & Lee (1989) studied the Gm and Km alleles (or allotypes) in 74 Chinese populations and found that there is an obvious genetic distinction between the southern and northern Chinese. By analysing a comprehensive dataset comprising 38 classical markers, Du & Xiao (Du et al. 1997) validated the genetic differentiation of southern and northern Chinese and showed that they are separated approximately by the Yangtze River. Chu et al. (1998) showed that such a north–south division can also be observed in Chinese populations using DNA markers (i.e. microsatellites). This genetic division is also consistent with multidisciplinary evidence in archaeology, physical anthropology, linguistics and surname distribution. Furthermore, the results from Chu et al. (1998) demonstrated that the north–south division is not limited to Chinese populations and is in fact a reflection of a north–south division of East Asian populations. In the last few years, genetic data on mtDNA and Y chromosomes have been accumulated at an unprecedented pace for East Asian populations. Again, a north–south division of East Asians was observed not only with Y chromosome markers . These observations provided convincing evidence of a north–south division in East Asian populations. ***

However, this well-established fact was not accepted without being challenged. Karafet et al. (2001) did not observe the north–south division in East Asians using a set of Y chromosome markers that are less polymorphic in East Asian populations and that over-represent the lineages brought in by recent admixture. In a different study, Ding et al. (2000) examined mtDNA, Y chromosome and autosomal variations and failed to observe a major north–south division. The southern populations in their study are primarily the Tibeto-Burman (TB) populations, which have a recent northern origin, and therefore would blur the north–south distinction . A more extensive study of mtDNA lineages provided a much higher resolution and consequently a strong north–south division emerged. ***

The north–south division raises the question of whether the southern and northern East Asians (NEAS) are descendants of the same ancestral population in East Asia or originated from different populations that arrived in East Asia via different routes. To date, three main hypotheses have been brought forward on the entry of modern humans into East Asia: (I) entry from Southeast Asia followed by northward migrations , (ii) entry from northern Asia followed by southward migrations , and (iii) southern and NEAS are derived from different ancestral populations, i.e. southern populations from Southeast Asia and northern populations from Central Asia. Therefore, to understand the mechanism of genesis and maintenance of the north–south division, much needs to be learnt about the origin and migration of the East Asians. ***

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Genetic studies of human diversity in East Asia ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Modern Humans in Tam Pà Ling Cave in Laos Over 75,000 Years Ago

A fragment of a human leg bone found in sediments Tam Pà Ling cave in Laos is believed to be as old as 86,000 years old. Human fossils — a partial skull and jawbone dating to between 46-63,000 years old — were first discovered there in 2009. Excavations there have revealed hundreds of animal and human fossils, suggesting Homo sapiens lived there for as long as 56,000 years.

The evidence from Tam Pà Ling cave has not been ironclad but has gotten better over time. James Ashworth of the Natural History Museum in London wrote: Initially it wasn’t known if the sediments containing the bones had been washed into the site, or whether they represented a gradual build up over time. After a decade of research at the cave, the scientists now are confident about their findings. Vito Hernandez, a PhD student and co-author of a 2023 study on the cave, says, ‘The results of our microarchaeological analyses have given us a better appreciation of the ground conditions in Tam Pà Ling in the past, allowing for a more precise interpretations of how and when these early modern human fossils were buried in this part of the cave.’ [Source: James Ashworth, Natural History Museum, June 15, 2023]

Human fossil remains designated as TPL2. From Tam Pa Ling‘s cave in Laos. (A) Mandible in norma verticalis; (B) mandible in norma lateralis, right side; (C) mandible in norma latelaris, left side; (D) mandible in norma facialis external; (E) mandible in norma facialis internal (F) mandible in norma basilaris; (G) occlusal view of the right M3

Studies of the sediment revealed that it had naturally built up over time, with heavy rains in the monsoon season washing it into the cave over thousands of years. There was little evidence that it had been disturbed after being put down, suggesting that it could be reliably dated. To do this, the team used a mixture of techniques, including luminescence dating and U-series dating. The former allows scientists to work out when an object was last exposed to light, and therefore when it was buried. U-series dating, meanwhile, looks at the decay of Uranium over time to give an estimate of age.

Together, these have allowed the team to create a timeline of the site. The earliest human fossil found at the site is a newly discovered leg bone around 77,000 years old, but could be even older. Meanwhile, the youngest fossil is at least 30,000 years old, suggesting that the cave was an important region for many generations of Homo sapiens. While attempts to extract DNA from the fossils failed, their presence alone shows that humans were living around Tam Pà Ling for 10,000 years longer than previously thought. The task for scientists now is to explain what happened to these early pioneers.

‘If the growing picture of a pre-60,000-year-old dispersal to east Asia is confirmed, then this implies that the DNA of these earlier populations has not come through to the present day at detectable levels,’ Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum says. ‘This means that these older populations either died out, or they were replaced or swamped by a more substantial later spread of Homo sapiens into the region.’

Whatever happened to the first Homo sapiens at Tam Pà Ling, humans would continue to visit the region for thousands of years. The researchers suggest the cave might have been used by people gradually migrating across Asia and down towards Australia. Along the way, it’s possible that Homo sapiens would have encountered its relatives which lived in the area, such as Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis. Finding more fossils in southeast Asia could help to reveal what relationship they might have had, as well as larger questions in

55,000-Year-Old Modern Humans from Tam Pa Ling Cave in Laos

A human skull was found in 2009 and a jaw was discovered in late 2010 from cave site known as Tam Pa Ling (The Cave of Monkeys). in Laos. Dated to 46,000 to 63,000 years ago, the bones are the oldest modern human fossil found in Southeast Asia. The discovery pushed back modern human migration to that region by about 20,000 years earlier than thought. [Source: Kambiz Kamrani in Physical Anthropology, anthropology.net 11, April 2015]

According to Archaeology magazine; The Tam Pa Ling Cave fossils are providing insights into how the first Homo sapiens settled Southeast Asia and later Australia. Archaeologists Fabrice Demeter of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris and Laura Shackelford of the Illinois State Geological Survey analyzed the skull. According to Shackelford, it does not show any evidence that the individual’s ancestors interbred with Homo erectus, a hominin species that lived in the area for more than one million years. The skull itself is small and belonged to a young adult at least 18 years old. No artifacts were found with the bones, but the cave’s location, far from the coast, shows that modern humans migrated through the river valleys and into the mountains of Laos as they continued their trek toward Australia, where they arrived at least 40,000 years ago. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology, October 5, 2012]

But what is interesting is the mix of features, says Shackelford. In addition to being incredibly small in overall size, they has a mixture of traits that combine typical modern human anatomy, such as the presence of a protruding chin, with traits that are more common of our archaic ancestors like Neanderthals – for example, very thick bone to hold the molars in place.

According to pbs.org: “63,000 years ago, a woman died in the forested hills of northern Laos. She may have been looking for food or shelter - perhaps she was escaping a tropical storm. Whatever the reason, her final resting place was Tam Pa Ling Cave. Here she remained, until 2008, when archaeologists uncovered her skull and jawbone. Human fossils are extremely rare in the tropics because the climate is too wet to preserve bone, so this was a major discovery. It is the oldest definitively modern human skull found anywhere in Asia. People like her must have left Africa thousands of years previously, traveled deep into Asia and adapted to life in the rainforest – encountering a variety of new animals, parasites and plants. In the absence of flint, they learnt how make tools and weapons using the local supergrass, bamboo. Anthropologists have long assumed that humans migrated out of Africa by hugging the coast - but Tam Pa Ling is a thousand miles inland. Instead, it seems people moved along Asia’s river valleys, which served as natural corridors through the continent. [Source: pbs.org]

First Humans in Sumatra 70,000 Years Ago

Modern humans were in Sumatra at least 70,000 years. In a study published in Nature in August 2017, scientists said they had accurately dated two human teeth first discovered on the island of Sumatra in the late 19th century, showing our ancestors were living there between 73,000 and 63,000 years ago. Genetic studies have placed humans in Southeast Asia by 60,000 years ago, but the previous oldest fossil evidence dated to just 45,000 years. [Source: Hannah Osborne, Newsweek, Published August 9, 2017]

Hannah Osborne wrote in Newsweek: The teeth were found in the Lida Ajer cave in the Padang Highlands of Sumatra. They are the first evidence of humans in Indonesia and the first evidence of humans occupying a rainforest environment. The finding has surprised archaeologists. Kira Westaway, an environmental scientist at Macquarie University in Australia, told Newsweek, "The earliest evidence for modern humans using rainforests environments [was from] around 45,000 years ago in Niah Cave, Borneo." These regions seem an unlikely place for early humans to live. "Rainforests are difficult environments to live in," says Westaway. "They require technological innovations and sophisticated hunting techniques for survival." This research reveals that people inhabited the rainforest far earlier than previously suspected. "Finding an early modern human presence in a rainforest location is remarkable as it suggests that these skills were in place by this time," says Westaway.

Chris Clarkson, who led the Australian research but was not involved with this work, calls the new discovery very timely. "The dating of fossil modern-human teeth from Lida Ajer 73,000 to 63,000 years ago provides the missing link—that is, the first unequivocal evidence of modern human presence in [Southeast Asia] likely just prior to their first appearance in Australia at 70,000 to 60,000 years ago," says Clarkson, an archaeologist at the University of Queensland. "This is a really fantastic result and will renew the search for modern-human sites in Southeast Asia of comparable age, including evidence of their way of life."

45,000-Year-Old Cave Art Found in Sulawesi

Rock art and hand prints found in caves in Sulawesi have been dated to nearly 40,000 years ago. Deborah Netburn wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Archaeologists working in Indonesia say prehistoric hand stencils and intricately rendered images of primitive animals were created nearly 40,000 years ago. These images, discovered in limestone caves on the island of Sulawesi, are about the same age as the earliest known art found in the caves of northern Spain and southern France. The findings were published in the journal Nature. "We now have 40,000-year-old rock art in Spain and Sulawesi," said Adam Brumm, a research fellow at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and one of the lead authors of the study. "We anticipate future rock art dating will join these two widely separated dots with similarly aged, if not earlier, art." [Source: Deborah Netburn, Los Angeles Times, October 8, 2014 ~\~]

“The ancient Indonesian art was first reported by Dutch archaeologists in the 1950s but had never been dated until now. For decades researchers thought that the cave art was made during the pre-Neolithic period, about 10,000 years ago. "I can say that it was a great — and very nice — surprise to read their findings," said Wil Roebroeks, an archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the study. "'Wow!' was my initial reaction to the paper... This spectacular finding suggests that the making of images on cave walls was already a widely shared practice 40,000 years ago." ~\~

A well-preserved painting of a pig from the Leang Tedongne cave on Sulawesi may be the oldest known animal image. Dating back 45,500 years, the nearly life-size depiction of a small native warty pig was rendered using red ochre on a rock art panel and appear to be part of a narrative scene. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2021]

As many as 300 caves in the region have been found to contain paintings, making it one of the largest concentrations of early human wall art. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March 2021]

See Separate Article: EARLY HUMANS IN SULAWESI, INDONESIA AND THEIR 45,000-YEAR-OLD CAVE ART factsanddetails.com

Niah Caves and Early Humans in Borneo

In 2018, scientists announced that modern humans or hominins had established themselves in Borneo — at the Niah Caves complex in Sarawak — by 65,000 years ago, a figure that far exceeded the previous estimate of 35,000 to 40,000 years ago. This new timeline was determined after five pieces of microlithic tools dated to 65,000 years ago and a human skull dated to 55,000 years old were discovered in Trader Cave, part of the Niah Caves complex, during excavation work. The discovery makes Trader Cave the oldest archaeological site in Borneo and the oldest archaeological site with human remains in Malaysia. The cave also has provided the earliest reliably date arrival time for modern human – in Southeast Asia. [Source: Sam Chua, Borneo Post, October 22, 2018]

Also in 2018, Borneo was added to a growing list of places with some very old cave art sites. National Geographic reported: Countless caves perch atop the steep-sided mountains of East Kalimantan in Indonesian Borneo. Draped in stone sheets and spindles, these natural limestone cathedrals showcase geology at its best. But tucked within the outcrops is something even more spectacular: a vast and ancient gallery of cave art. Hundreds of hands wave in outline from the ceilings, fingers outstretched inside bursts of red-orange paint. Now, updated analysis of the cave walls suggests that these images stand among the earliest traces of human creativity, dating back between 52,000 and 40,000 years ago. That makes the cave art tens of thousands of years older than previously thought. [Source: Maya Wei-haas, National Geographic, November 7, 2018]

But that's not the only secret in the vast labyrinthine system. In a cave named Lubang Jeriji Saléh, a trio of rotund cow-like creatures is sketched on the wall, with the largest standing more than seven feet across. The new dating analysis suggests that these images are at least 40,000 years old, earning them the title of the earliest figurative cave paintings yet found. The work edges out the previous title-holder—a portly babirusa, or “pig deer,” in Sulawesi, Indonesia—by just a few thousand years (since this article was written older animal figures have bee n found in Sulawesi)

See Separate Article: EARLY HUMANS IN BORNEO: NIAH CAVES 40,000-YEAR-OLD ROCK ART factsanddetails.com

Tabon Man, Callao Cave and the First Modern Humans in the Philippines

Its estimated that the first people reached the Philippines at least 50,000 years ago, perhaps by a land bridge from Asia that was exposed when oceans receded during the Ice Age. Very old hominin remains have were found in Tabon Cave on the island of Palawan. It is possible there were people much earlier than this. People have lived in Australia for 60,000 years. Palawan was connected to Southeast Asia by a land bridge during the Ice Ages. Other Philippine islands such as Luzon were not.

Tabon Man refers to remains discovered in the Tabon Caves in Lipuun Point in Quezon, on the west coast Palawan in the Philippines. They were discovered by Robert B. Fox, an American anthropologist of the National Museum of the Philippines, in May 1962 and consist fossilized fragments of a skull of a female and the jawbones of three individuals dating back to 16,500 years ago. Later evidence of hominins dated to 47,000 years ago was found at the site (See Below). [Source: Wikipedia]

Tabon Caves appears to have been a kind of Stone Age factory, with both finished stone flake tools and waste core flakes having been found at four separate levels in the main chamber. Charcoal left from three assemblages of cooking fires there has been Carbon-14-dated to roughly 9,000, 22,000, and 24,000 years ago. The right mandible of a modern human (Homo sapien) which dates to 29,000 B.C., was discovered together with a skullcap. The Tabon skull cap is the oldest skull cap of a modern human found in the Philippines, and is thought to have belonged to a young female. The Tabon mandible is the earliest evidence of human remains showing archaic characteristics of the mandible and teeth.

In 2023, Archaeology magazine and Popular Science reported: It’s difficult to ascertain how long humans have used plant materials to make textiles, ropes, and baskets since these objects rarely survive in archaeological contexts, particularly in the world’s tropical regions, where warm and humid air breaks down green matter easier than stone or bone fragments.. However, microscopic imaging of three 39,000-year-old stone tools from the Tabon Caves identified plant residues and wear patterns likely caused when hard bamboo or palm stalks were stripped into pliable fibers that were easier to weave or tie. This is by far the earliest known evidence of people manipulating plants in Southeast Asia. These findings were described in a study published June 30, 2023 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE. [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, July 1, 2023; Archaeology magazine, September-October 2023]

See Separate Article: FIRST HOMININS IN THE PHILIPPINES: 709,000 YEAR OLD TOOLS, HOMO LUZONENSIS AND TABON MAN factsanddetails.com

Negritos and the First People of the Malay Peninsula

Indigenous groups on the Malay Peninsula can be divided into three ethnicities, the Negritos, the Senois, and the proto-Malays. The first inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula were most probably Negritos, Mesolithic hunters were probably the ancestors of the Semang, an ethnic Negrito group who have a long history in the Malay Peninsula. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Another remain dated back to 9000 BC dubbed the "Perak Man" and tools as old as 75,000 years have been discovered in Lenggong, Malaysia. The oldest habitation discovered in the Philippines is located at the Tabon Caves and dates back to approximately 50,000 years; while items there found such as burial jars, earthenware, jade ornaments and other jewelry, stone tools, animal bones, and human fossils dating back to 47,000 years ago. Human remains are from approximately 24,000 years ago. +

The earliest anatomically modern humans skeleton in Peninsular Malaysia, Perak Man, dates back 11,000 years and Perak Woman dating back 8,000 years, were also discovered in Lenggong. The site has an undisturbed stone tool production area, created using equipment such as anvils and hammer stones. The Tambun Cave paintings are also situated in Perak. From East Malaysia, Sarawak's Niah Caves, there is evidence of the oldest human remains in Malaysia, dating back 40,000 years. [Source: Wikipedia +]

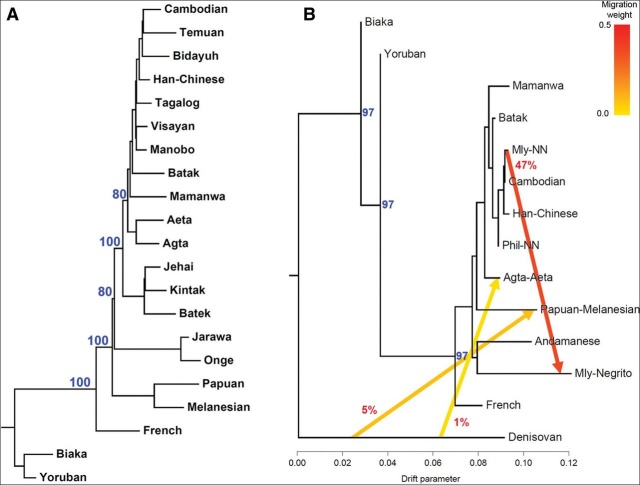

The Negritos are of an unknown origin. Some anthologist believe they are descendant of wandering people that "formed an ancient human bridge between Africa and Australia.” But it turn their genetic affinities are much more similar to the people around them. This suggests that Negritos and Asians had the same ancestors but that Negritos developed feature similar to Africans independently or that Asians were much darker and developed lighter skin and Asian features, or both. The Semang are probably descendants of the Hoabinhian rain forest foragers who inhabited the Malay Peninsula from 10,000 to 3,000 year ago. After the arrival fo agriculture about 4,000 years, some became agriculturalist but enough remained hunter gatherers that they survived as such.

The Senoi appear to be a composite group, with approximately half of the maternal DNA lineages tracing back to the ancestors of the Semang and about half to later ancestral migrations from Indochina. Scholars suggest they are descendants of early Austroasiatic-speaking agriculturalists, who brought both their language and their technology to the southern part of the peninsula approximately 4,000 years ago. They united and coalesced with the indigenous population. +

The Proto Malays have a more diverse origin, and were settled in Malaysia by 1000 B.C. Although they show some connections with other inhabitants in Maritime Southeast Asia, some also have an ancestry in Indochina around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum, about 20,000 years ago. Anthropologists support the notion that the Proto-Malays originated from what is today Yunnan, China. This was followed by an early-Holocene dispersal through the Malay Peninsula into the Malay Archipelago. Around 300 BC, they were pushed inland by the Deutero-Malays, an Iron Age or Bronze Age people descended partly from the Chams of Cambodia and Vietnam. The first group in the peninsula to use metal tools, the Deutero-Malays were the direct ancestors of today's Malaysian Malays, and brought with them advanced farming techniques. The Malays remained politically fragmented throughout the Malay archipelago, although a common culture and social structure was shared. +

In the early days the Semang may have interacted and traded with the Malay settlers when the arrived but relations soured when the Malays began taking them as slaves and then they retired into the forests. The Semang and other similar groups became known as the Orang Asli in peninsular Malaysia. Even though they were regarded as supposedly "isolated" they traded rattan, wild rubbers, camphor and oils for goods from China

See Separate Articles: EARLY HISTORY OF MALAYSIA factsanddetails.com; Lenggong Valley Archaeological Cave Sites in Malaysia factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024