CLIMATE AND WEATHER IN JAPAN

autumn in Nagano A major feature of Japan’s climate is the clear-cut temperature changes between the four seasons. From north to south, Japan covers a range of latitude of some 25 degrees and is influenced in the winter by seasonal winds blowing from Siberia and in the summer by seasonal winds blowing from the Pacific Ocean. In spite of its rather small area, Japan is characterized by four different climatic patterns. Hokkaido, with a subarctic weather pattern, has a yearly average temperature of eight degrees centigrade and receives an average annual precipitation of 1,150 millimeters. The Pacific Ocean side of Japan, from the Tohoku region of northern Honshu to Kyushu, belongs to the temperate zone, and its summers are hot, influenced by seasonal winds from the Pacific. The side of the country which faces the Sea of Japan has a climate with much rain and snow, produced when cold, moisture-bearing seasonal winds from the continent are stopped in their advance by the Central Alps and other mountains which run along Japan’s center like a backbone. The southwestern islands of Okinawa Prefecture belong to the subtropical climate zone and have a yearly average temperate of over 22 degrees, while receiving over 2,000 millimeters of precipitation. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

On the summer solstice the sun rises just before 4:30am in Tokyo and reaches a zenith of 78 degrees above the southern horizon at 11:40am and sets around 7:00am. In Sapporo in northern Japan the sun reaches a zenith of 59 degrees on the summer solstice. In the southern Ryukyu Islands just north of the Tropic of Cancer in southern Japan the sun reached a zenith of 89 degrees.

The Japanese government is having a hard time coming up with the funds to construct new weather satellites and could be caught short without satellites when the current satellites stop working.

The National Research Center for Disaster Prevention (NRCDP) has a corrugated-steel Rainfall Simulator, mounted on railroad tracks, that can produce anything from drizzle to a typhoon. This devise is rolled on to artificial hills to get a sense of when dangerous mudslides begin.

In June 2009, there were reports of fish, tadpoles and frogs falling from the sky and landing in parking lots in four cities in Ishikawa Prefecture. Some think that the creatures were picked up by a tornado-like weather formation and dropped on the land but most think the animals fell from the bills of birds like herons that were taking the frogs and tadpoles back to their nests to feed their young. After media coverage tadpoles were spotted all across the country. Ornithologists said they didn’t think the phenomena was caused by birds.

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: LAND AND GEOGRAPHY OF JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLIMATE AND WEATHER IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; STORMS, FLOODS AND SNOW IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TYPHOONS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; TYPHOONS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; NATURAL RESOURCES AND JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources on Climate and Weather: Good Photos of the Seasons at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Land and Weather Chapter stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp Japan Meteorological Agency Japan Meteorological Agency ; Weather Underground wunderground.com/global/JP ; Weather Channel Weather Channel ;World Climate World Climate ; Accuweather Accuweather ; Climate Data climatetemp.info/japan ;Wikipedia article on Geography of Japan Wikipedia ;

Good Websites and Sources of Storms and Floods: Weather Warnings from Japan Meteorological Agency jma.go.jp/en/warn ; Marine Warnings from Japan Meteorological Agency jma.go.jp/en/seawarn ; Wikipedia article on Snow Country in Japan Wikipedia ; Landslide Distribution Map bosai.go.jp/en ; BBC Picture Gallery of Flood in Japan news.bbc.co.uk ; Academic Paper of Flood Maps in Japan internationalfloodnetwork.org ; Tornados in Japan Survey by the American Meteorological Society ams.allenpress.com ; BBC report on 2006 Tornado bbc.co.uk

Typhoons: Typhoon and Hurricane Basics aoml.noaa.gov ; Data and Images from Pacific Typhoons eorc.jaxa.jp/ADEOS Typhoon and Hurricane Satellite Images and Photos fotosearch.com ; Video from Nasty Typhoon in Taiwan YouTube ; Typhoon Video YouTube ; Central Pacific Hurricane Center at the National Weather Service prh.noaa.gov ; Wikipedia article on Tropical Cyclones Wikipedia ; National Hurricane Center at the National Weather Service nhc.noaa.gov ; Jet Propulsion Laboratory Images of Typhoons jpl.nasa.gov/images ;

Typhoons in Japan : Typhoon and Tropical Cyclone Information from the Japan Meteorological Agency Japan Meteorological Agency ; Video of Typhoon Surfing in Japan YouTube ; Brochure on Typhoons in Japan pdf file rms.com/Publications ; Good Japan Times article on Typhoons in Japan search.japantimes.co.jp ; Digital Typhoon Information from the and United States Navy agora.ex.nii.ac.jp/digital-typhoon ; Ise-Wan Typhoon Wikipedia article on the 1959 Ise-wan Typhoon (Typhoon Vera) wikipedia.org/wiki/Typhoon_Vera ; U.S. Navy Report on the 1959 Ise-wan Typhoon pdf file usno.navy.mil and usno.navy.mil ; Lessons from the Isewan Typhoon pdf file katrina.lsu.edu/downloads/Typhoon_Isewan

Japan’s Climate

Most of Japan has four distinct seasons, which are somewhat similar to those in the United States. The Japanese climate is generally mild thanks to the tempering effect of the ocean. But because the islands of Japan stretch 1,400 miles from north to south there are great variations, ranging from tropical in Okinawa (with the same latitude with Key West, Florida) to blustery and snowy in Hokkaido (with the same latitude as Quebec).

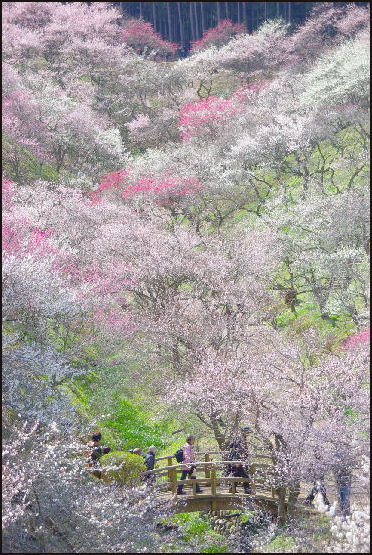

Spring cherry trees in Yoshino Springs is ushered in by plum blossoms in March and cherry blossoms in April, and is pleasant and sometimes rainy. Autumn begins in September and is characterized by falling leaves, crisp, cool, days and rice harvests. Northern Japan and temples with maple trres have pretty autumn colors.

Winter tends to be mild on the Pacific side, with many sunny days, while the Japan Sea side tends to be colder and more overcast. Winter in Hokkaido and northern Honshu are shaped by frigid northwest winds from Siberia, which occasionally sweep across from the Asian continent bringing snow to coastal regions facing the Sea of Japan and to the central mountain regions. Hokkaido, northern Honshu and the mountains in the interior of Honshu are among the snowiest places on earth.

Tsushima Current and Japanese Weather

A warm ocean current known as the Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows northeastward along the southern part of the Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, known as the Tsushima Current, flows into the Sea of Japan along the west side of the country. From the north, a cold current known as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea of Japan from the north. The mixing of these warm and cold currents helps produce abundant fish resources in waters near Japan. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “About 12,000 years ago...the global climate began warming, and the strength of the warm Kuroshio, or Japan Current increased. This current, the western Pacific equivalent of the Gulf Stream, sweeps northward out of Southeast Asian, running up the Ryukyu Islands then twisting clockwise along the Pacific Ocean coasts of Kyushu, Shikoku and Honshu before heading out to sea.” [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, November 11, 2010]

“About 8,000 years ago, the Kuroshio became so powerful that a branch current broke off and smashed through the gap between Japan and the Korean Peninsula. This great river of warm water, called the Tsushima Current, now flows northeastward through the Sea of Japan as far as western Hokkaido and the southern tip of Sakhalin.”

“The creation of the Tsushima Current was a momentous event that radically altered Japan's climate and vegetation. The dry, cold winter winds blowing across the Sea of Japan from Siberia now pick up moisture evaporated from the warm waters, which they then deposit as heavy snow all along the north and west facing flanks of Japan's mountain ranges. As the climate grew milder and wetter, the islands' grasslands gave way to the great tracts of dense forest we see today.”

More Frequent Extreme Weather in Japan?

In January 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Japan witnessed weather irregularities in the summer of 2012. Typhoon No. 12 registered the largest rainfall on record, and Typhoon No. 15 saw evacuation recommendations issued to as many as 1.22 million people in Aichi Prefecture and elsewhere. According to statistics from the Meteorological Agency, heavy rain in Japan has been on the rise over the past 100 years or so. Although the cause behind the increased rainfall remains unknown, some scientists believe it may be linked to global human activities. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 18, 2012]

“As Masahide Kimoto, vice director of the University of Tokyo's Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, puts it: "As the earth's climate changes, antidisaster preparations should be thoroughly reviewed, starting with city planning. Conventional wisdom can no longer cope with the situation.”

“In the case of extreme weather conditions, experts have said preventative measures have limits. Recently, a Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism Ministry council discussed transitioning away from conventional thinking that aims to prevent flooding in all rivers. The council also said it would be difficult to prevent all damage in the event of future, harsher disasters.

Four Seasons of Japan

The seasons are very important to Japanese. Japan has four distinct seasons and there are certain events, specific activities and foods associated with each one. The changing seasons is a theme addressed in “The Tale of Genji”, a 10th century novel. In the “Kokin Wakashu”, an anthology of waka poems compiled in the 10th century, the poems are arranged in the order of the seasons. Even today Japanese often begin polite correspondence with some comment on the seasons. “Kisetsukan” (“the feel of the season”) is an important concept in Japanese cultural and artistic traditions. Haiku puts a strong emphasis on the season. Every poem must contain an appropriate “kigo” (“season word”). There is even a book that lists all recognized kigo by season.

The seasons and foods are often linked together. May is associated with the new rice crop and October is associated with the rice harvest. The “katsuo” bonito season is in early summer. “Koromogae” describes the season change of clothes in which, for example, one refrains from wearing linen until after the summer rainy season has ended.

“Autumn: From the end of summer through September, Japan is often struck by typhoons. Typhoons originate from large masses of tropical lowpressure air in the North Pacific between the latitudes of approximately 5 and 20 degrees, and are the same phenomenon as hurricanes. Colorful foliage is the symbol of autumn throughout Japan. and cyclones in other parts of the world. When a typhoon begins to take shape, it gradually moves north. Every year, during this period, around 30 typhoons form, of which on the average about 4 reach Japan, sometimes causing great destruction. After the middle or latter part of October, Japan enjoys generally clear weather; it is neither hot nor cold. The country also enjoys especially fine weather at the beginning of November. Many of the trees take on bright autumn colors, making this time of the year, together with the time of new greenery in the spring, a truly beautiful season. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

“Winter: Toward the end of November, cold seasonal winds begin blowing over Japan from the continent. These northwesterly winds pick up moisture over the Sea of Japan and drop much of this moisture in the form of rain and snow on the western side of Japan as they are impeded in their eastern advance by the ridge of mountains that runs through the central part of the country. The Hokuriku region (Fukui, Ishikawa, Toyama, and Niigata prefectures), which faces the Sea of Japan and is separated from other regions of Japan by high mountains, is known for its deep snows. By contrast, the Pacific side of the country enjoys generally clear skies during the winter season. In Tokyo, despite the fair skies, winter temperatures average around 5 degrees, a difference of 25 degrees from summer temperatures of 30 degrees or more. The islands of Okinawa Prefecture in the far southwest have a subtropical climate with less marked temperature differences between the seasons. Winter temperatures there are much more moderate than in other parts of the country.

“Spring: When winter nears its end, the cold seasonal winds blowing from the continent become weaker and more intermittent. At this time, low pressure air masses originating in China enter the Sea of Japan; these give rise to strong, warm southerly winds which travel toward this low-pressure zone from the Pacific Ocean. The first of these winds is called “haru ichiban”. While it announces the warmth of the coming spring, it sometimes causes avalanches and, crossing the mountains to the side of the country facing the Sea of Japan, it is at times responsible for exceptionally hot and dry weather and can even become the cause of large fires. In early spring, plum blossoms start to bloom, followed by peach blossoms. During the last ten days or so of March, the cherry blossoms so beloved by the Japanese people begin to bloom.

Summer can be very muggy, hot and humid, especially in August and September. In many places they say it is so humid in the summer that you can walk and swim at the same time and so hot you can fry rice on the sidewalk. It is not usual for swimmers have to wait in line for an hour to get a ticket for a 20 minute dip in a local swimming pool. Southeast winds blow across Japan from the Pacific in the summer bring rain to coastal regions facing the Pacific.

Summer Rainy Season in Japan

“Before the arrival of real summerlike weather, Japan has a damp rainy season known as “tsuyu”. From May until July, there is a highpressure mass of cold air above the Sea of Okhotsk to the north of Japan, while over the Pacific Ocean there develops a high-pressure mass of warm, moist air. Along the line where these cold and warm air masses meet, known as the “baiu zensen”, or “rainy season front,” there often develop areas of low-pressure warm air. Thus the “baiu zensen”, which extends from southern China over the Japanese archipelago, causes prolonged periods of continuous rainfall. After the middle of July, high-pressure air masses over the Pacific Ocean become predominant and the rainy season comes to an end as the “baiu zensen “is pushed northward. Seasonal winds from the Pacific Ocean bring warm, moist air to Japan, and the country has hot summer weather with many days when temperatures rise to more than 30 degrees centigrade.

The humid rainy season — caused by the Bai-u front — lasts for about a month, from mid-June to mid-July in most parts of the country. But because Japan is strung out over such a large area latitude-wise the rainy season ends in Okinawa in June around the time it in starts Hokkaido and northern Japan. On most days of the rainy season it rains for one two hours or less. The temperatures are significantly cooler than later in the summer.

During the rainy season Japanese greet each other with expressions like “ainiku no soramoyo” (“unfortunate weather”) and “ashimoto no warui naka” (“not a good day to be out”). It has been said that it rains so much in Japan that many Japanese must have been frogs or freshwater snails in their previous life. Some people like the rainy weather. Commenting on drizzly rainy season day, the poet Kyukin Susukida (1877-1945) wrote: “My sense of peace is so complete that I don’t even feel like reading my favorite book.” He preferred instead to sit around and probe the deepest depths of his soul.

In the summer of 2009 the seasonal rain front stalled over Japan bringing heavier-than-usual rains, a longer rainy season and cooler temperatures and even spawned a couple of tornados. In some places where the rainy season usually ends by mid July it extended into August. These conditions were caused the weakness of the Pacific high and its slow development which was tied to weak ariel convection activity near Philippines.

The typhoon season lasts from late summer to early autumn. Most typhoons that strike Japan arrive in September and generally come ashore in southern Japan and dissipate as they move north. A summer heat wave sets on after the June rainy season is over In many places it is very hot with little relief many days in a row.

Winter Winds in Japan

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The first kogarashi or "leaf-wilting wind" of 2010 was officially recorded in the Kanto and Kinki regions on October 26. These kogarashi are defined as north winds with speeds of 8 meters per second or more, and are considered to indicate that the winter pattern of air pressure, with highs in the north and northwest, is in place. These north winds will over the next few months bring heavy snows to the Sea of Japan side of the islands.” [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, November 11, 2010]

“The high pressure systems that comprise the winter pattern originate over Siberia and send cold, dry winds whipping down in the southeast direction. During the glacial period, these winds kept Japan cold and dry, and the vegetation was dominated by open grasslands interspersed with groves of fir, spruce and other hardy conifer trees.”

“Although the kogarashi have already started blowing, at this time of early winter the air pressure patterns are still shifting. Cold wintry days are interspersed with periods of absolutely gorgeous weather: warm and sunny all day long, but with a light cooling breeze and thin wispy cloud cover to gently soften and diffuse the light.”

Hot Summers in Japan

A summer heat wave sets in many areas of Japan after the June rainy season is over. In many places it is very hot with little relief many days in a row. Areas near mountains sometimes experience high temperatures associated with the foehn wind effect. The hottest areas in the summer in Japan are on the Japan Sea and in Saitami Prefecture near Tokyo. Heat generated in Tokyo is blown against the mountains in Saitama.

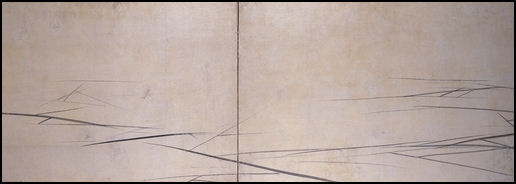

Cracked Ice Cool View for Summer

an 18th century painting by Maruyama Okyo

Unusually high summer temperatures have been attributed to global warming, rising air currents and very strong high pressure over the Pacific Ocean. In 2007 high temperatures were blamed on rising air currents created by the La Nina phenomena in the Pacific and rising air currents in India, creating a funneling effect that strengthened the rising air currents over Japan.

When extremely hot days and tropical nights continue for extended periods the asphalt of the roads and walls of buildings do not cool down sufficiently at night, resulting in high room temperatures in office buildings from early in the morning, This boosts demand for air conditioning and electricity.

During heat waves in Japan the sale of air conditioners, beer soft drinks and watermelons increases. Japanese, Chinese and Koreans crave watermelons when the weather is hot and give them as summer present at Bon events. Demand was so strong for watermelons in the heat wave of 2007 that shortages were reported and prices were significantly higher than what they were in 2006 and 2005.

Heat Island Effect in Japan

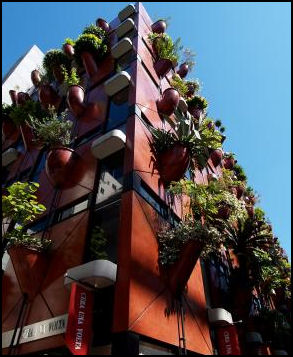

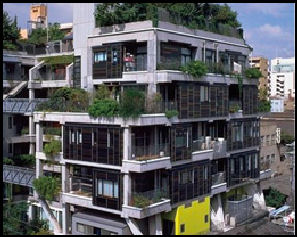

Green building intended to

combat summer heat Tokyo and Osaka and other large urban areas suffer from the “heat island” effect. Temperatures in central Tokyo have risen 3 degrees C in the 20th century and are 2 C higher than the national average. More of this difference is attributed to the heat island effect than global warming. Temperatures in some parts of Tokyo increased 5.2 degrees between 1900 and 2000, five times more than global warming.

Tokyo and other large cities act like radiators. During the day asphalt roads and roofs, car bodies and concrete building absorb heat. At night they release it, making the nights much warmer than they otherwise would be. Japanese cities are particularly bad because they don’t have many trees or parks.

In the summer the heat increases have been greatest between midnight and 5:00am, causing more “tropical nights,” and producing microclimates that trap air pollution and make storms more likely downwind from the city. In the winter, the extra heat means no snow in places that once had snow. In the autumn, leaves that used to change color in November now change in December. In the spring, the cherry blossoms are gone when the traditional cherry tree season party begins.

Combating the Heat Island Effect in Japan

another green building The Japanese are attempted to battle heat island effect by replacing dirt fields in school yards with grass ones and using water-retentive blocks made from crushed, recycled asphalt and concrete as paving material. The water-retentive blocks are just as strong as ordinary paving blocks but reduce heat and produce a cooling effect when water is evaporated from them. Because the blocks are made from recycled material they are also environmentally friendly.

Tokyoites battle the heat island effect by splashing water all over the place on pavement and concrete. Around Tokyo station trees were planted on rooftops, water-retentive pavement has been installed and a building was knocked down to create a wind channel to dissipate some of the heat that builds up there.

People living in top floor apartments are combating the “heat island” effect by installing roof-top gardens. New technology, water systems and grass allow gardens to built without damaging existing roofs. City planners have discussed building pipelines under the cities to bring in cool water from local bays. Air conditioner sales have boomed in recent years.

Record Hot Summers in Japan

Japan had an unusually hot summer in 2004. Temperatures topped 30 degrees C a record 41 days in a row in Tokyo, with a record high of 39.5 degrees C on July 21. Some researchers blamed the heat wave on a high pressure system over Tibet that in turn forced a high pressure system to settle over Japan. Its downward flowing air caused monsoon convection currents to raise temperatures on the ground. Other researchers blamed the heat wave on a “mock El Nino” over the Pacific Ocean, caused by warm water temperatures that sent air upwards in the Pacific and sent it downwards over Japan. This descending air caused high ground temperatures.

girls in maid costumes

splashing water to cool down

the streets and sidewalks The summer of 2007 was the hottest ever in many places. In Tokyo the average temperature was over 29 degrees. High temperatures of 38 and 39 even 40 degrees were recorded everyday in various cities. Electricity demand was so high during the height of the heat wave in 2007 that Tokyo Electric Power Co took emergency measures for the first time in 17 years. A couple dozen people died from heatstroke, including a several that were indoors, and hundreds were hospitalized for heatstroke, including high school students competing in a mountain-climbing event. On one day, 19 people drowned, 15 of them in the ocean.

Record temperatures of 40.9 (105.6 degrees F) were recorded in Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture near Tokyo and Tajima in Gifu Prefecture in August. A thermometer sign hit 43 degrees in Kumagaya The previous record 40.8 was recorded in Yamagata in July, 1933. Temperatures over 40 degrees were also record in Mino, Gifu Prefecture; Koshigaya in Saitama Prefecture and Tatebayashi, Gunma Prefecture. A total of 101 cities in Japan recorded record temperatures in the summer of 2001.

In the summer of 2008, July was hot but August wasn’t too bad. A record-breaking heat wave in July, in which temperatures reached 38 and 39 degrees in Gifu and Aichi, saw 12,747 people taken by ambulance to the hospital with heat stroke — 3.5 times the number the figure for the same month the previous year. Nationwide 33 people died. In Nagoya a 64-year-old jogger died of heat stroke. In Nara, am 80-year-old man died while doing farm work. More than 40 percent of those treated for heatstroke were 65 or over.

The highest the temperature for September is 39.7 temperature set in Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture in 2000. In 2011, according to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency, the number of people taken to the hospital by ambulance due to heatstroke from July through September was about 39,000 nationwide. About 17,000 of them, or more than 40 percent, were elderly.

Heat Wave in Japan in 2010

The summer of 2010 was the hottest ever. Temperature routinely topped 38 degrees C in a places across Japan. Tokyo and Osaka had several days of temperature over 37 degrees. Parts of Hokkaido suffered record heats waves. In southern, central and western Japan the heat continued unabated for weeks on end.

Japan’s average temperatures from June to August 2010 were the highest ever based on comparing temperatures at 17 locations nationwide during that time and comparing that with data kept since 1898. In August monthly average highs reached new records in 77 of 154 major observation stations. Tokyo experienced a record 71 “tropical days” in which the mercury exceeded 30 degrees C or higher. There were 41 days in which the maximum temperature exceeded 35 degrees C in Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture and Tatebayashi, Gunma Prefecture.

Many places recorded record number of days above 35 degrees C and temperature in eastern and western Japan were between 1.8 and 2 degrees above normal in August. The heat wave was blamed on high pressure zones normally located in the Pacific and over Asia that took up residence over Japan, preventing cool air from coming in.

The high temperatures were credited with boosting the economy as consumers bought drinks, air conditioners, special clothing and medical devices to beat the heat. Among the ways that people stayed cool were eating cold noodles and having “cool shampoos” with refrigerated menthol shampoo.

In 2010 a record-high 1,718 people died from heatstroke, of whom 80 percent were people aged 65 or older. Between early May and September more than 54,000 people were taken to hospital by ambulance for treatment for heat stroke. A large percentage of those who died were elderly people who died indoors. There was a larger number of summer deaths in July (96,000-8,000 than 2009) and August (97,000-7,000 than 2009) than in other years. Demographers said the hot weather contributed Japan’s population decline in 2010 of 123,000 people.

The heat also took its toll on animals. There were fatal cases of heat stroke suffered by dogs. Dogs don’t sweat and pugs and bulldogs are particularly vulnerable because their breathing passages and airways are so narrow. More than 1,200 cows, 657 pigs and 289,000 chickens died as result of the heat. High sea temperatures caused by record heat was blamed for low catches of fish such as saury and salmon, the average ocean temperatures around Japan were 1.5 degrees higher than usual.

The average temperature in 2010, was 0.85 C higher than the 30-year average and equaled the forth highest recorded jump since records have been kept. Japan’s average temperatures from June to August 2010 were the highest ever but low temperature from March to May dragged the yearly average down .

Average temperatures in late June 2011 in both east and west Japan were the hottest since the Meteorological Agency began collecting data in 1961. The number of people taken to hospitals in June for heatstroke came to 6,877 throughout the country, triple the figure recorded in June 2010.

Record Hot August and September in 2012

On how hot it was in August 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The mean temperature was 1.2 C higher than average, but total rainfall was just 61 percent of the norm. There were 21 extremely hot days in August, in which the highest temperature exceeded 35 C, in Kumagaya, Saitama Prefecture, compared with seven days in an average year. Central Tokyo had four extremely hot days, compared with 1.7 in an average year. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 1, 2012]

Heat-related ailments caused severe health problems. According to the Fire and Disaster Management Agency of the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry, 56 people died of heat-related ailments and 35,529 were taken to the hospital in an ambulance in July and August last year. This year, from July through Aug. 26, 67 people died and 37,419 had to be taken to the hospital.

Jiji Press reported: “Japan recorded the hottest September in more than 110 years this year, due to an extremely strong high pressure system in the Pacific, the Japan Meteorological Agency said. The average September temperature at 17 observation points across the country, where the effects of urbanization on temperature are minimal, was 1.92 C higher than usual--the largest increase since statistics were first compiled in 1898--the agency said. The temperature hit a record high at 51 of 154 observation points across the country. [Source: Jiji Press, October 3, 2012]

Cool Share in the Summer of 2012

On efforts to conserve electricity in the summer of 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “An increasing number of people participated in "cool share" initiatives, in which they turned off air conditioners at home and visited public facilities and other places that provide air-conditioned summer retreats. In Arakawa Ward, Tokyo, the ward office held a makeshift rakugo event, inviting young comic storytellers, and placed small children's pools inside the ward's facilities. A ward office official said, "Usage of the facilities has increased by more than 10 percent from last year, when rolling power outages were implemented." Coca-Cola (Japan) Co. has suspended cooling functions in vending machines from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m., when electricity consumption peaks daily.The measure has been in place since July, and will continue through September for 800,000 machines in most areas. As a result, the company said it cut daytime electricity consumption by 15 percent. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 1, 2012]

In Tokyo Electric Power Co.'s service area, this summer's peak consumption hit a high of 50.78 million kilowatts on Thursday. The ratio of the consumption rate to TEPCO's supply capacity on the day was also at its highest this summer, at 93 percent. Though the peak figure increased from last summer's 49.22 million kilowatts, it was 15 percent lower than the 59.99 million kilowatts seen in 2010. A TEPCO spokesman said, "Users have contributed to about 6 million kilowatts of reduced consumption.”

Global Warming in Japan

See Environment

Yellow Dust from China and El Niño and Japan

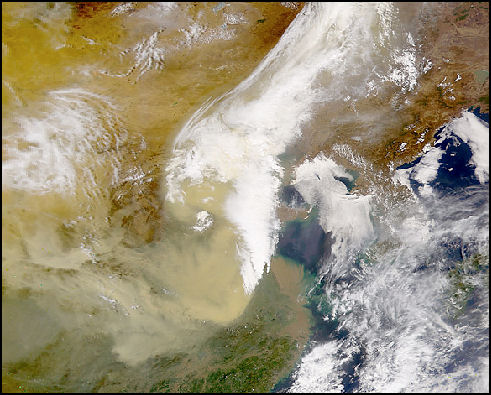

Yellow dust from Gobi deserts and other deserts in western and north-central China and Mongolia blows into Korea and Japan. The seasonal winds that bring the yellow dust are called “Huwangsa” (yellow sand). Some of the dust and sand is the same yellow dust and sand that gives the Yellow River its color.

dust from a Gobi storm heading towards Japan

The yellow sand and dust dirties windshields and laundry and can cause respiratory problems. Some Japanese suffer from red, itchy eyes and runny noses and other allergy-like symptoms in the yellow sand season. Doctors the sand does not cause allergy but rather exaggerates symptoms.

Between 1980 and 1999 there was only one year in which yellow sand particles were observed on more than 40 days. But since 2000 — apart from 2003 and 2004 — yellow sand particles have been observed on more than 40 days every years, reaching 55 days in 2002. In the mid 2000s, the sand started appearing more in northern Japan and Hokkaido. Record amounts yellow sand from China and Mongolia hit Japan in the spring of 2006. Yellow sand hit Tokyo in April for the first time in six years.

Much of the yellow sand and dust originates in Gobi Desert and Ocher Plateau in China and Mongolia. After the snow thaws there the sand and dust is exposed and picked by strong spring winds that lift up the sand and dust to several thousand meters, where it is carried by westerly winds to Japan. On Mt. Fuji there is a device that measures yellow sand, dust and soot carried on winds from China.

El Niño causes a wet summer and prolonged monsoons in Japan and Korea. During the La Niña, Japan and Korea, are cooler, The El Niño of 1997-98 caused typhoons in Japan. There were fears it was push snow away from Nagano and cause the 1998 Olympics to be a dismal failure.

Tracking Bugs with Radar May Lead to Forecasts of Thunderclouds

In June 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “Using meteorological radar to track insects and spiders carried by wind, a team of researchers has observed the formation of thunderclouds, it has been learned. The findings by the researchers, including some from the Meteorological Agency's Meteorological Research Institute (MRI), may lead to technology that will allow meteorologists to predict the generation of cumulonimbus clouds, the researchers said. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 4, 2012]

Cumulonimbus clouds produce thunderstorms, and sometimes tornadoes.Thunderclouds are spawned when an ascending current is generated at a place where cool air meets warmer air carried in winds blowing from different directions. Using a meteorological radar system installed at Haneda Airport, the research group observed insects and other tiny creatures floating about 500 meters above the ground in western Tokyo on the afternoon of Aug. 7, 2011.

“The bugs, which the researchers said probably included Mymaridae bees and spiders, were believed to be buoyed by winds at a place where cool wind from Tokyo Bay converged with warm wind on land. The study group subsequently confirmed the formation of thunderclouds directly above the site while tracking the bugs, mostly about one millimeter across, as they were carried into the sky on columns of air, the team said.

See China, Nature, Weather

Image Sources: 1) 2) 3) JNTO 4) British Museum 5) Ray Kinnane 6) Hector Garcia site 7) NASA

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013