TYPHOONS

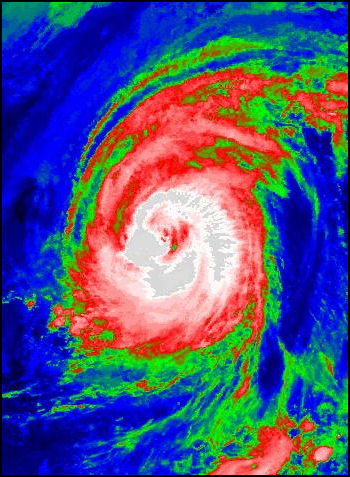

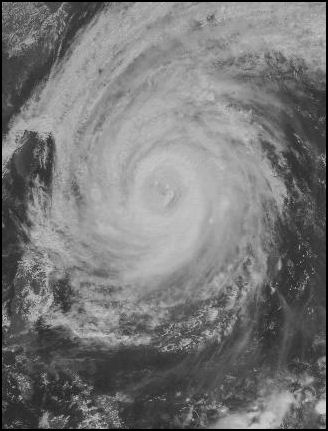

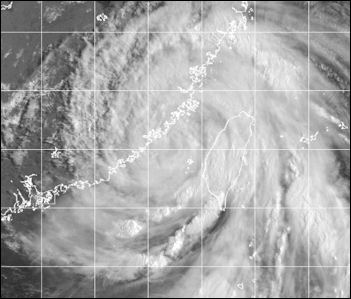

Typhoon Megi in October 2010

A typhoon is defined as a tropical cyclone in the western Pacific. Typhoons generally track in a westward or northern direction, and occur most frequently in a region of the western Pacific and east Asia that includes the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, southern China, South Korea, southern Japan, Guam, the Marianas Islands and parts of Micronesia. They generally do not occur south of the Philippines and blow themselves out if they travel west of Vietnam or into the interior of China.

A typhoon is essentially the same thing as a hurricane, which is defined as a strong tropical storm with winds over 75 miles per hour, occurring in the west Atlantic and the eastern Pacific, particularly in southeastern North Americas and the Caribbean. Similar storms in the Indian Ocean are called tropical cyclones. Ones that strike Australia are called willie willies. Cyclone is also a catch all phrase which describes all low pressure systems over tropical waters and includes typhoons and hurricanes. All these storms feature super heavy rain as well as high winds.

The word “typhoon” comes from the Cantonese word "tai feng." The approach of a typhoon is heralded by large waves, a storm surge, and falling barometric pressure. As it gets nearer mountains of cumulus clouds appear and wind squalls intensify, climaxing with a sweeping wall of dense clouds with furious winds and torrential rain. Describing a South China Sea storm in 1935, one American captain wrote: "A terrible crash was heard! The vessel trembled like an aspen-leaf...with the sea pouring in over the bow, and the topsails shivering like so many rags." Joseph Conrad described the storms in his novels “Lord Jim” and “Typhoon”.

The typhoon season lasts from the early summer to early autumn, often coinciding with the monsoon season in Southeast Asia and the wet season in eastern Japan. The main typhoon and hurricane season is from June to November. Sometimes they appear as early as May and as late as December. Storms can be particularly fierce in years of the El Niño. Usually more damage is caused by the heavy rain than by the winds.

In Japan typhoons are given numbers and are named in order of occurrence. In other Asian countries since 2000 they have been given names. Each member of a group called the Typhoon Committee, comprised of 14 Asian countries, including Japan, provide 10 names for a total of 140 names

See Separate Articles: HURRICANES AND TYPHOONS: PHYSICS, FORMATION AND DAMAGE factsanddetails.com HURRICANES AND TYPHOONS AND GLOBAL WARMING factsanddetails.com ; STUDYING, TRACKING AND PREDICTING TYPHOONS AND HURRICANES factsanddetails.com factsanddetails.com; TYPHOONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; Websites on Typhoons: Typhoon and Hurricane Basics aoml.noaa.gov ; Data and Images from Pacific Typhoons eorc.jaxa.jp/ADEOS Typhoon and Hurricane Satellite Images and Photos fotosearch.com ; Video from Nasty Typhoon in Taiwan YouTube ; Typhoon Video YouTube ; Wikipedia article on Tropical Cyclones Wikipedia ; National Hurricane Center at the National Weather Service nhc.noaa.gov

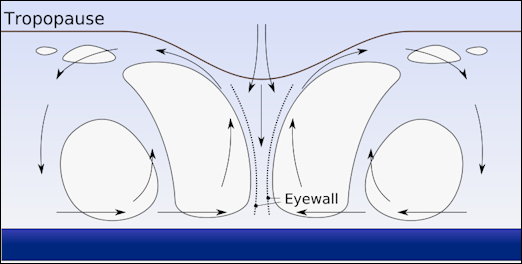

Typhoon Physics

warning alert in China Hurricanes and typhoons in the northern hemisphere have an eye and thunderstorm-producing cumulus clouds that spiral out in a clockwise direction from the eye. They eye is 5 to 25 miles wide and is relatively calm, sometimes windless. Strong winds blowing towards the center of the area of extreme low pressure and cirrus streamer clouds radiating in a east or southeast direction are bent by the Coriolis affect. The most destructive part of the storm is usually the northern, leading side of the storm. The east side of a typhoon generally is more devastating than the west side.

The “eyewall,” an area just beyond the eye, is the region of the storm with the most intense winds. It is often only a kilometer or so wide but it interacts with the rings of thunderstorms that produce the heaviest winds and rains and its behavior and dynamics are crucial to the behavior of the storm as a whole. The eyewall is shaped by two opposing forces: 1) moist, warm air from inside the eye, which can feed the eyewall, strengthening it; and 2) dry air from outside the eye that can slowly bleed into it, and calm it down.

Air flowing from high pressure to low pressure causes winds. If the difference between high pressure and low pressure is great, intense circulation is generated, causing a powerful storm. As air spirals into a low-pressure zone warm humid air and warm sea surface winds meet and ascend, causing clouds to billow upwards. Further lowering of air pressure can cause winds to swirl even faster towards the center.

The deflecting action of the Earth’s rotation spins the developing cyclone (counterclockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere). When water in the ascending clouds cools and falls as rain heat energy is produced, which further warms the storm, lowering the pressure and making the storm stronger. The cyclone can continue to strengthen as long as it remains over warm water and is not destroyed by vertical wind shear — winds traveling at different speeds at lower and high altitudes — which can cut off the top of a storm breaking up its energy producing engine.

Types of Typhoons

Supertyphoons are very destructive. They are defined as typhoons with winds over 150 miles per hour. Such storms produce horizontal rain and can measure several hundred miles across, cover thousands of square miles and reach an altitude of almost ten miles. The largest storm on record, the 1979 typhoon Tip, produced gale force across a 650 mile area.

The power generated by a major hurricane or typhoon is said to be equal to half a million nuclear bombs. The power of an average storm is said to be equal to 1.5 trillion watts — the equivalent to about half the world’s entire electrical generating capacity.

Large storms, typhoons and hurricanes are defined as: 1) a tropical depression; 2) a tropical storm (less than 74 miles per hour); 3) Category One (between 74 and 95 miles per hour); 4) Category Two (between 95 and 110 miles per hour); 5) Category Three (between 111 and 130 miles per hour); 6) Category Four (between 131 and 155 miles per hour); and 7) Category Five (more than 155 miles per hour).

In Asia, different countries have different systems for identifying typhoons. Some countries such as Japan use numbers. Others use names. These days the names of typhoons that appear in the popular press seem to alternate between Korean names, Chinese names and Japanese names, with maybe a Vietnamese name thrown in from time to time.

typhoon-hurricane profile

Typhoon Formation

Typhoons develop in an area of the tropical Pacific at a latitude between 10 and 20 degrees north. They usually begin as westward-drifting “waves” of clouds drawn into an area of low pressure around the Caroline Islands of Micronesia (between Hawaii and the Philippines in the Pacific) and grow into westward-moving tropical depressions.

As the clouds advance across the warm water they pick up energy as the water evaporates. At a critical point the clouds develop into a vortex of air that rotates in a counter-clockwise direction because of the Coriolis effect (see above). The water temperatures generally have to be above 80̊F for all this to occur. The warmer the sea surface temperature are, and the more warm, moist air there is, the stronger the storm will be.

A number of things have to come together for a typhoon to form. Among them are the presence of an initial low-pressure system that pulls the air to a particular spot in the ocean; the Coriolis effect spinning the air in a vortex; difference in wind speed in the upper and lower parts of the atmosphere that create horizontal “shear forces”; and the presence of cold air 10 miles up in the atmosphere.

Many so called “storm seeds” with the potential to become typhoons form in the summer west of the International Date Line in an area of the tropical Pacific at a latitude between 10 and 20 degrees north. They usually begin as westward-drifting “waves” of clouds drawn into an area of low pressure around the Caroline Islands of Micronesia (between Hawaii and the Philippines in the Pacific) and grow into westward-moving tropical depressions, which are groups of thunderstorms.

Because the Caroline Islands of Micronesia are breeding grounds for typhoons they rarely get hit by fully developed storms. Typhoons usually pass north of Palau. As the clouds advance across the warm water they pick up energy as the water evaporates. At a critical point the clouds develop into a vortex of air that rotates in a counter-clockwise direction because of the Coriolis effect (see above). The water temperatures generally have to be above 80̊F for all this to occur. The warmer the sea surface temperatures are, and the more warm, moist air there is, the stronger the storm will be.

Typhoon Dynamics

Factors that influence typhoon development include water temperatures and rainfall amounts in the Pacific; El Niño (which produces high-level winds that blow the top off typhoon clouds); and stratospheric jet-stream wind patterns. Scientist also believe that typhoons can be influenced by seemingly unrelated things like the atmospheric temperatures above Singapore.

According to a study by scientists at the University College London high sea temperatures are the most reliable indicator of increased typhoon and hurricane activity. The reasoning is that warmer seas cause more water to evaporate. As the water rises, latent heat is released which provides the energy for a low pressure cell to develop into a hurricane.

Typhoon Engine

Typhoon Tokage Typhoons are self-feeding and self-reinforcing events fueled by: 1) evaporated water that releases energy when it condenses back into water; and 2) driving rapid updrafts that cause water to evaporate from the ocean, forming self-sustaining vortexes of swirling clouds and high winds. The dynamics of all this — especially of forces than can cause a storm to suddenly intensify — remain little understood. Among the clues that a storm is about to intensify are the presence of chimney clouds called hot towers that can reach as high as 11 milies into the atmosphere.

Rapidly moving air over warm water absorbs unusually large amount of water vapor through evaporation. As the air converge at the center of the storm, it rises. As the air rises, it cools and some of the water vapor condenses into droplets. That process release energy in the form of “heat cf condensation.” [Source: Washington Post, ✳]

The heat is released into a column of air that is already warmer than the air outside the storm. There can be as much as a 30̊F difference between air in the eyewall and air at the same altitude outside the storm. The heat dissipates slowly, in part because the air is contained in a rotating system. Meanwhile, the newly released reheated air continues to rise, eventually losing more moisture and condensation and releasing more heat. In this way a large and powerful typhoon can influence its environment in such a way as to allow the storm to get even bigger and stronger.✳

When the rising air exits from the system, sometimes as high as 50,000 feet above the sea surface, it is cold and relatively dry. As it departs more air is pulled in at the bottom of the storm, continuing the cycle. The energy from the warm water beneath the storm is vital to keeping the whole thing going. When a typhoon goes over cool water or land it tends to fall apart. High upper atmosphere winds are also great typhoon killers. They can sometimes sheer the tops off of a typhoon and cause it to suddenly collapse.

Hurricanes maintain and gain strength over the sea and lose strength when the go overland. Islands are often so small they little effect. The intensity of a storm is also related to its interaction with the sea. Warm water at the top of the ocean provides fuel. As the storm spins, it churns the water beneath it, bringing cooler water from the depths. The cooler water acts as a brake to slow the engine down. Some of the most intense storms are feed by warm water that is hundreds of meters deep and the breaking action of cooler water does not occur. Large waves can also slow a storm down by blunting the winds that created them.

Damage from Typhoons

Typhoons can cause millions or even billions of dollars in damage. Buildings slide down hillsides; valleys flood; villages disappear under landslides and mud slides; roads and bridges are washed away; crops become waterlogged, or are blown over or uprooted, or covered in mud. Destruction levels can be particularly high when a storm stalls and strong, driving rains persist for hours or even days, or when the storm slams into mountains, producing particularly large amounts of rain. Some typhoons are so powerful they blow plankton and small sea creatures into the sky, where they float around on clouds.

Typhoon Tokage

Usually much more damage and death is caused by rains than winds. People die from being hit by flying debris or falling trees or crushed in collapsed building but are more likely to die from drowning in flooded rivers or from suffocating under rain-induced mud slides and landslides. Most victims from really deadly storms die from storm surges — masses of ocean water that are pushed forward by the winds — that can penetrate several miles inland. The surges are particularly deadly if they occur at high tide.

Typhoons often do the most damage on low coral islands which are sometimes inundated with waves that can reach a height of 30 meters at sea and storm surges that sweep water across the entire island, annihilating every tree and hut in their path. Modern buildings and houses with cinder block walls and metal roofs are usually strong enough to withstand the winds of strong typhoons but thatched-roof huts and shanties are easily blown over or crushed by falling trees. Palm trees also blow over pretty easily because they don't have a deep root system.

Long term damage and hardships from typhoons are caused by sickness and starvation as water supplies become contaminated; cholera and dysentery; poisonous snakes flooded out of their dens; damaged crops and stored food; and the disruption or destruction of transportation routes used to bring in relief supplies. Over the longer term fields and agricultural land may be is destroyed and rivers may be rerouted. Where factories are washed away and infrastructure is damaged, people may begin migrating out. In poor countries there is inevitably not enough money to fix everything.

The danger from typhoons increases with time as coastal areas become more developed and urban areas sink as result of the drawing of underground water. Global warming is predicted to raise sea levels, making the situation even more dire.

There are examples of typhoons and hurricanes striking certain areas and dramatically altering the coastline. Barrier island are particularly vulnerable, there are cases of such island that were formed thousands if years ago that have been whittled down to islets and remnants in 150 years by storms, subsiding land and rising sea levels.

Areas Hit by Typhoons

Typhoons frequently hit Taiwan, Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Hong Kong and southern China during a typhoon season that lasts from early summer to late autumn. They gather strength from warm sea water and tend to dissipate after making landfall.

Most typhoons usually track north and first strike places like Guam, Saipan, Taiwan and Okinawa and then either move northward into Japan or Korea or move westward into the Philippines, Vietnam, or China. Because the Caroline Islands of Micronesia are breeding grounds for typhoons they rarely get hit by fully developed storms. Typhoons usually pass north of Palau.

The island of Okinawa lies right in the heart of Typhoon alley. The islands there get hit by an average of seven storms a year, some of them with winds exceeding 190 miles per hour. in the old days, fisherman's families there kept their finances in the name of the wife because fisherman often went out to sea and didn't come back.

Taiwan also gets hit quite a bit. After typhoons Taiwanese fishermen can sometimes be seen on the shore collecting washed up herring-like fish with chopsticks.

More Frequent Typhoons?

from a typhoon in 1939

Some climatologists believe that the surge in the number of typhoons and hurricanes in recent years may be linked to global warming which warms up the seas and provides more energy for weather phenomena that develop into severe storms. In 1995, there were unusually high number of hurricanes. Coincidently or not, 1995 also had the highest global surface temperatures on record. and ocean temperatures in the Atlantic were the highest ever recorded. In one of the 11 years between 1995 and 2005 there were unusually high numbers of hurricanes.

There are generally more major hurricanes in years when the sea surface temperatures are higher than average. Sea temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean rose steadily from 2000 to 2004, and each of these years had an “above normal” hurricane season with the exception of 2002 which was a weak El Nino year. But the Atlantic patterns fluctuates and are not consistent. The mid 1920s through the 1960s were very active when temperatures were relatively cool. The 1970s and the early 1990s were quiet.

There was a particularly high number of typhoons in 2004. By August of that year there had already been nineteen, 35 percent more than normal. Ocean temperatures in 2004 were around two degrees F higher than normal. The year 2005 was a bad year for hurricanes. There were 27 named tropical storms — including Katrina, which killed more than 1,000 people and lef much of New Orelans and the neigboring coast in ruins’so many the list of storm names was extended with Greek letters. There were a record 15 hurricanes, including foru category 5 storms.

Stronger Typhoons?

Super typhoons stronger than Hurricane Katrina that devastated New Orleans are expected to hit the Asia-Pacific region over the coming decades with global warming being one of the causes. Some scientist have suggested that global warming will increase the rain fall from typhoons by 20 percent and increase their winds by 10 percent. Damages is also worsening because more intense typhoons are coinciding with rising seas levels. But not all the damage is the fault of the storms. Damage typhoons is also increasing because more people than ever live on coastlines or other vulnerable areas.

Since the 1970s, typhoons that have struck East and Southeast Asia have become stronger — and presumably will continue to get stronger in the future — with the likely but not conclusive villains being climate change and warming ocean waters near the coasts, according to a study published in September 2016 in the journal Nature Geoscience. "If you have warming coastal water, it means that typhoons can get a little extra jolt just before they make landfall," Kerry Emanuel, a professor of meteorology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said.”That’s obviously not good news" Warming ocean waters intensify typhoons because they provide more heat and energy to the storm.. "The fuel that powers the [storm] is an enormous transfer of heat from the ocean to the atmosphere when you have strong winds blowing across the surface," Emanuel said [Source: Alessandra Potenza. The Verge, September 5, 2016]

Typhoon Bilis The Verge reported: “The researchers looked at two different data sets to calculate the intensity of the tropical storms from 1977 to today: the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC), managed by the US Navy and Air Force, and the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA). They found that typhoons that strike East and Southeast Asia have intensified by 12 to 14 percent. They also found that the number of category 4 and 5 typhoons — those with wind speeds between 130 mph and 157 mph or higher — increased to around seven per year today, from less than five in late 1970s.

“The researchers also looked at how the ocean water temperatures in the northwest Pacific changed between 1977 and 2013. They found that the ocean waters off the coasts of East and Southeast Asia, where typhoons got stronger, became a lot warmer. In the open ocean, instead, where temperatures haven’t increased that much, the intensity of typhoons hasn’t changed significantly. That means that the stronger storms are probably due to the warming waters, which are known to funnel energy into tropical storms.

“Instead of looking at global trends, the study focuses on specific typhoons that make landfall in highly populated areas and usually make severe damage. "It’s the first time that anybody has really looked in a concrete way at such a regional trend," Emanuel says. But the study also falls short of saying why exactly typhoons are getting stronger: is it human-made climate change, or just variations that happen naturally on our planet? With only about 40 years worth of data, we can’t really tell. "The caveat with the study is the data they’re dealing with," says Suzana Camargo, a research professor at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University, "but it’s a problem there’s no way around." Before 1977, the JMA didn’t provide wind measurements of typhoons, says Wei Mei, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the lead study author. And not a lot of satellite measurements were done before the 1970s, Mei says.

Typhoon Warning System

Typhoons frequently occur in Taiwan, which has its own storm warning system that alerts Taiwanese citizens of impending storms over the TV and radio. The first warnings are a 1) Storm Advisory, which warns a storm could strike within 48 hours; a 2) Sea Warning, which projects a storm will be within 60 miles of the shore within 24 hours; and a 3) Land warning, which projects a storm will hit land within eight hours.

Condition 24: destructive winds can be expected in 24 hours. At this stage Taiwanese are advised to fill their gas tanks, make sure they have plenty of flashlight batteries and candles and put away loose boards or other items that can be picked up by the wind and injure people.

Condition 12: destructive winds can hit within 6 hours. At this time Taiwanese are told to move valuables upstairs, and fill the bathtub and containers with water.

Condition 6: destructive winds can hit within 3 hours. Taiwanese are told to turn up refrigerator to maximum cold and try not to open it; unplug nonessential appliances; stay indoors; use the phone only for emergencies; do not travel; and tape large windows that might be exposed to heavy winds.

Emergency Alert: Destructive winds and rain are occurring over the island. Stay indoors, move furniture away from the windows, roll up rugs and place them on furniture if there is a possibility of flooding. If power goes out use refrigerator as little as possible.

Some scientists say the best place to seek shelter in a storm is a concrete parking garage which is unlikely to collapse because it solidly built and winds blow through it rather than push on it. Moreover the winds that blow through it subside once they are inside the structure

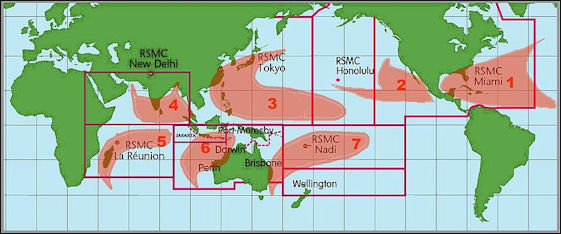

tropical cyclone zones

Image Sources: Typhoon News weblog, NASA, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2022