ZHAO LIANG

Zhao Ling Zhao Liang is another highly-acclaimed Chinese independent documentary filmmaker whose best known work is “Petition”. On his start in film Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: Frustrated with his work as a television cameraman in his hometown, Dandong, on the frigid border with North Korea, Mr. Zhao’s way out was a one-year fellowship to the venerable Beijing Film Academy, where directors like Zhang Yimou and Chen Kaige had trained. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, August 13, 2011]

At screenings, Mr. Zhao became exposed to the works of foreign directors whose slow, methodical styles greatly influenced him. His favorite was Andrei Tarkovsky, the Soviet director. “The Russians, that culture, they really respect knowledge, they respect art,” he said. “You can feel that the intellectuals of that culture are tough. They have backbone. They really are thinking of their people.” “A culture like that, with that kind of intellectual, there’s hope,” he added. “China, the way China is, you hardly see people like that.”

In 1996, Wong wrote, Mr. Zhao began taking his camera to a shantytown in Beijing called the Petitioners’ Village, where people with grievances from all over the country camp out while trying to plead their case at the central petition office. “I remember quite clearly one of my middle-school teachers telling me that I was a stone with sharp, jagged edges, but that I would turn into a smooth river stone as I grew older,” Mr. Zhao said. “During the years while I was making this film, I felt like I was getting sharper and sharper instead.”

All the while, Mr. Zhao took on various cameraman jobs and put on exhibitions of his photography and art videos. He met Ai Weiwei — the the internationally known artist detained for nearly three months in 2011 during a broad crackdown on liberal intellectuals — when they both exhibited at a show in Finland. After the death of Ai Qing, Mr. Ai’s father and a famous poet, Mr. Zhao sat in the hearse with his friend as it drove past Tiananmen Square. In the early 2000s, when Mr. Zhao was at a low point, Mr. Ai lent him $750. Mr. Zhao called Mr. Ai when he believed officers were following him during the filming of “Petition”: “Weiwei, if one day I disappear, you have to come find me,” he said.

See Separate Articles: SIXTH GENERATION FILMMAKERS AND ACCLAIMED ART HOUSE MOVIES FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com ; JIA ZHANGKE factsanddetails.com ; INDEPENDENT FILM MOVEMENT AND DOCUMENTARY FILMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RECOMMENDED AND ACCLAIMED CHINESE INDEPENDENT DOCUMENTARY FILMS factsanddetails.com ;

Websites: Chinese Film Classics chinesefilmclassics.org ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com; 100 Films to Understand China radiichina.com. dGenerate Films is a New York-based distribution company that collects post-Sixth Generation independent Chinese cinema dgeneratefilms.com; Internet Movie Database (IMDb) on Chinese Film imdb.com ; Wikipedia List of Chinese Filmmakers Wikipedia ; Shelly Kraicer’s Chinese Cinema site chinesecinemas.org ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Resource List mclc.osu.edu ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com; Wikipedia article on Chinese Cinema Wikipedia ; Film in China (Chinese Government site) china.org.cn ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The New Chinese Documentary Film Movement: For the Public Record” by Chris Berry, Xinyu Lu, et al Amazon.com; "Independent Chinese Documentary — From the Studio to the Street" by Luke Robinson Amazon.com; “DV-Made China: Digital Subjects and Social Transformations after Independent Film” by Zhen Zhang, Angela Zito, et al. Amazon.com; “Postsocialist Conditions: Ideas and History in China’s “Independent Cinema, 1988-2008" by Xiaoping Wang Amazon.com; “Memory, Subjectivity and Independent Chinese Cinema” by Qi Wang Amazon.com; “Independent Chinese Documentary: Alternative Visions, Alternative Publics” by Dan Edwards Amazon.com; “From Underground to Independent: Alternative Film Culture in Contemporary China” edited by Paul G. Pickowicz and Zhang Yingjin Amazon.com; “Filming the Everyday: Independent Documentaries in Twenty-First-Century China” by Paul G. Pickowicz and Yingjin Zhang | Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of Chinese Film” by Yingjin Zhang and Zhiwei Xiao Amazon.com; “The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Cinemas by Carlos Rojas and Eileen Chow Amazon.com;

Zhao Liang on Filmmaking

As of 2011 Zhao had made five independent documentaries including “Crime and Punishment”, “Petition” and “Together”. He lives in Beijing. His wife is Thai. She and their two children live in Bangkok, or at least they did. Zhao told Slant magazine:“I'm doing all right these days. I follow my heart. It takes me at least a few years to make one film, so I would be pretty satisfied if I made 10 more films in my life, which is why I don't want to waste any of my time. You see, this film cannot be publicly screened [in China], but when I see my friends enjoying it, I feel pretty good. After all, if this film had to follow the censorship it wouldn't have been meaningful. You have seen my film Together [made in co-operation with the state government]? How horrible was that? I don't want to do that again. [Source: Alex Subler, Slant Magazine, Translation by Yasi Xu and Xuanzi Zhang, March 16, 2016]

“When I first started making documentaries, I was compelled by social responsibility, but now I have changed my mind. After all, I have realized that my films have made very little difference in terms of societal improvement. And also, with the understanding that I have nowadays, I see that the society cannot be changed by a few top professionals. A change in the society needs more than just a moment. Changing society through artworks would take hundreds of years. Therefore, it's impossible for art to have real meaning and in that aspect I'm a disappointed middle-aged man. Now all the works I do are for myself, even though there's a lot of social issues involved in my films. I wouldn't deny it, as I no longer see my work as a catalyst for creating social benefit. The reality is dark. If you want to change the world, it's better to study politics and enter a powerful corporation or organization. That would be more direct way to change society.

“There are many voices from China's high government that are saying they want to promote good art in the country, but then so much of the good art being made can't be shown. As an artist, what's your take on this paradox? In order to improve, the government has to change its standard for judging good art from bad. Because what we see as good art isn't the same as what they see right now. What documentaries do is to break lies and to tell the truth. Is the government willing to face the truth? If they don't change how they view art, there's never going to be a harmony between them wanting good art and having good art reach the masses.

"Paper Airplane”(2001) was one of Zhao Liang's earliest films. Translator Cindy Carter, who worked on it, told Bruce Humes of Ethnic China: “Gritty early DV-generation documentary about heroin and the Chinese rock scene. The first film I ever subtitled, and I did it for free. Over a dozen years later, Zhao Liang and I have worked on 4 films together and he is one of China’s most prolific and respected indie directors. [Source: Bruce Humes, Ethnic China, May 14, 2012]

Zhao Liang’s Petition

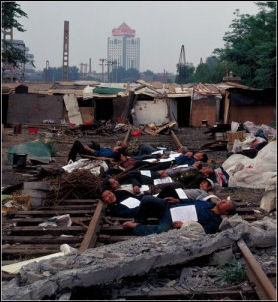

scene from Petition

“Petition” (Shang Fang) directed by Zhao Liang (2009) was shot over a period of 12 years. It documents the inhabitants of the Petition Village behind Beijing South Railway Station who have come from all over China seeking reparation from the Chinese government. The great Chinese independent filmmaker Jia Zhangke wrote: Petitioners from around the country carry their grievances to Beijing, hoping to attain the justice that they have been deprived. But in Beijing, their personal sufferings inevitably become politicized. Yingjin Zhang, a Professor of Chinese Literature at University of California, San Diego, wrote: this documentary contains so many disturbing images that keep the viewer on edge all the time. Concepts of human rights and social justice appear so powerless — yet all the more crucial — when petitioners are forced to live in a miserable condition in Beijing. Perseverance and bravery on the part of petitioners and activists are contrasted with the dismissal and violence from the bureaucracy in a world of irrationality and absurdity.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: “Petition” “is considered by many of its viewers to be a fearless work of art... It shows how the authorities muzzle and brutalize Chinese who, following an age-old tradition, travel to Beijing seeking redress for wrongdoing by local officials. The central story line of “Petition” follows the emotional toll that injustice takes on a woman and her daughter. In another story line, two petitioners are killed when they accidentally run into the path of an oncoming train while fleeing security officers. Fellow petitioners collect their body parts and call for the ouster of the Communist Party. “

An investigative documentary, “Petition: The Court of the Complainants” (2010) is about petitioners living on the fringes of China’s capital and their battles against a dysfunctional Chinese court system and their efforts to air their grievances against their local governments by traveling to Beijing where court cases demand much paperwork and they are made to wait for an indefinite period of time. The vast majority of petitioners are impoverished villagers from all over the country who travel far to the capital and typically end up waiting desperately in decrepit shantytowns for their cases to be settled. The film was special selection of the 2009 Cannes Film Festival.

In a review of the film, Joe Bendel wrote on his blog jbspins.blogspot.com, “They are the dregs of society. Scorned and maligned, they live a dangerous existence in crude shantytowns as they pursue their quixotic quest. They seek redress from the Chinese government and for filmmaker Zhao Liang, these “petitioners” are his country’s greatest heroes. Justice seekers, Zhao’s Petition stands as arguably the most damning documentary record of contemporary China to reach American theaters since the initial rise of the Digital Generation of independent filmmakers. [Source: Joe Bendel, jbspins.blogspot.com]

“Throughout Petition it is crystal clear the Chinese government has institutionalized corruption and hopelessly stacked the deck against the petitioners. Those victimized by unfair rulings have limited options locally for appeal (from the same corrupt bodies), so their only recourse is through the Kafkaesque “Petition Offices” in Beijing. Never in the film do we see the bureaucrats there actually give a petitioner satisfaction. They do keep records though. In fact, the local authorities have a vested interest in maintaining low petition numbers. Hence, the presence of “retrievers,” hired thugs who physically assault petitioners as they approach the petition office.

scene from Petition Petition is definitely produced in the fly-on-the-wall, naturalistic style of Jia Zhangke and his “d-generate” followers, but there is no shortage of visceral drama here. Each petitioner we meet has an even greater story of injustice to tell. Perversely, it seems it is those who do not take bribes who usually find themselves prosecuted in China. Petitioners are arrested, beaten, and even die under mysterious circumstances. Yet, it is through Zhao’s central figures, Qi and her daughter Juan, that we experience the emotional drain of the petitioning process with uncomfortable immediacy. Frankly, even if you have seen a number of Chinese documentaries, this film will still profoundly disturb you. Zhao deserves credit for both his significant investment of time and his fearlessness. Not surprisingly, filming is strictly prohibited in the Petition Offices, but that did not stop him from trying, often getting more than a slight jostle for his trouble. Indeed, Petition represents truly independent filmmaking. Petition is the cinematic equivalent of a smoking gun. It is impossible to maintain any Pollyannaish illusions of about the rule of law in China after watching the film. Yet, like Zhao, viewers will be struck be the petitioners’ indomitable drive for justice. May God protect them, because their government certainly won’t. A legitimately bold and honest film that needs to be seen.

Making and Promoting Petition

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times making Petitioners “was a Sisyphean mission, and a dangerous one: the system encourages security officers to abduct and punish the petitioners. Mr. Zhao shot 500 hours of footage, sometimes using hidden cameras inside the petition office. In the middle of the shooting, Mr. Zhao came to believe security agents were stalking him. The film was finished, and made its debut at the Cannes Film Festival in May 2009, but was immediately banned in China. Officers asked about Mr. Zhao in his hometown. He turned off his cellphone and fled to Tibet for three weeks. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, August 13, 2011]

Mr. Zhao said he never considered registering the film with the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television, also known as Sarft, the main regulator and censor of films. “Petition” eventually got financing from European investors, and Mr. Zhao finished a two-hour edit in 2009 in Paris. It was screened at Cannes in May. Variety called it “an unblinking record of human suffering."

Chinese journalists reporting on Cannes for state news organizations shunned the film. “There were reporters who booked interviews with me before the screening, but they all ran away afterwards,” Mr. Zhao said. The Chinese authorities swung into action: police officers began looking for Mr. Zhao, and friends warned him to lie low, prompting the trip to Tibet. Meanwhile, censors blocked any mention of “Petition” on Douban, an arts social networking site. “I heard some rumblings,” Mr. Zhao said. “I was really pretty nervous.” Screenings of “Petition” had to take place in secret, which frustrated him. “I want Chinese to see the film and have a better understanding of the environment in which they live,” he told an audience this March when “Petition” was screened at the Kubrick Café in Hong Kong.

Zhao Liang’s Crime and Punishment

Crime and Punishment poster

“Crime And Punishment” ( Zui yu Fa) directed by Zhao Liang (2007) documents the routine work of a small police station in Zhao Liang’s hometown in Northeast China (on the border between China and North Korea). Zhang Xianmin, a film producer and festival organizer, wrote: Zhao "is a local there, but has lived in Beijing as a conceptual and visual artist for many years. Despite what the film title might suggest, the lively daily events captured do not provoke deep reflection. But the arrangement of events, including the omission and lengthening of certain plot materials, as well as the philosophical investigation of the possibilities in human relations are all important issues that face contemporary documentary making.

Chris Berry of Kings College, London wrote: Like the best of Frederick Wiseman’s films, this observational takes us into the bureaucratic absurdities of a social institution in this case, a police station in Northeast China. Watching policemen naively letting him video them as they try to beat a confession out of a deaf mute is both one of the most shocking and funny moments in recent Chinese cinema. Film producer Karin Chien said: A prime example of how independent documentaries are on the vanguard of Chinese cinema, Crime and Punishment is an unprecedented look at the everyday workings of law enforcement in the world’s largest authoritarian society. With penetrating camerawork, Zhao Liang patiently reveals the police methods used to interrogate and coerce suspects to confess crimes — and the consequences when such techniques backfire. With a cold, objective eye, Zhao’s artistry withholds judgment in this cinematic slice of reality. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Dan Edwards of dGenerate Films wrote: “Crime and Punishment” provides an intimate snapshot of life inside a People’s Armed Police (PAP) station. Zhao told dGenerate Films he was only able to gain access to the station, located on the Chinese-Korean border in the remote northeast, because “these people are politically more naive and less politically savvy than their Beijing counterparts.” Zhao does not just exploit the officers’ naivety to expose their petty abuses of power however — the uniformed community provides a microcosm of the broader social structures informing the exercise of state power in contemporary China. [Source: Dan Edwards, dGenerate Films ]

“Crime and Punishment opens with the officers patiently folding their mattresses to form neat, identical piles on their beds. This extended sequence not only speaks of the conformist monotony of military life (the armed police are a paramilitary group organized similarly to the army), but also the thin line that separates those enforcing the law in China from those on the receiving end of the state’s coercive power. Like prisoners these men eat, work and sleep together in bare, whitewashed dormitories, kept at arm’s length from the townsfolk outside.”

“After this introductory sequence we follow the officers as they go about their duties, taking a call from a mentally disturbed man who claims he has found a body in his apartment, and raiding an illegal gambling den. After they arrest an alleged pickpocket in a market, we see the man questioned and casually beaten, first with kicks and punches, later with a leather strap. More surprising than the offhanded violence employed by the officers is their sheer incompetence. Although the film never spells out what differentiates the PAP from regular police, their military-style garb and an early scene in which a school principal praises their superior response time makes it clear this is an elite security unit. Despite their elevated status, as the film progresses it becomes embarrassingly evident these young men lack proper training or even an awareness of basic legalistic procedures.”

scene from Crime and Punishment “The alleged pickpocket, for example, is obviously unable to understand most of what is said to him, and his speech is largely unintelligible. After a comically inept “interrogation” the officers simply resort to beating him up. “Without a confession we can’t bring him to trial,” an exasperated policeman explains to Zhao Liang as the suspect is dragged away. None of the police appear to register that the man is either deaf or mentally impaired, and hence incapable of responding to their questions. Eventually we hear one of the officers admit to his superior that they are unable to communicate with the suspect and have absolutely no evidence against him. He’s later released without charge.”

“Later we see the police bring in an elderly farmer caught collecting scrap without a permit, a classic example of the petty bureaucratic regulations that govern every aspect of life in China. The average person just ignores most of these rules most of the time, creating problems when the police decide to arbitrarily enforce them. The son’s farmer nicely sums up the attitude of many when the old man calls him from the station for assistance: “Fuck those fuckers!” the son explodes. “All they do is dick around” those motherfuckers!” Unfortunately for the old man, his son’s diatribe is loud enough for the officers to hear.”

“After showing us the bumbling pettiness of much of the officers’ work, Crime and Punishment takes a more challenging turn when a group of young farmers are caught with an illegal load of timber. After the farmers are subject to the seemingly de rigueur beatings, a pair of officers accompanies one of them back to his village to collect evidence and photograph the stumps of illegally logged trees. In the village the officers are confronted by the man’s extended family living in a single cramped farmhouse. The suspect’s living conditions clearly touch a chord, and as they climb the hill behind the village to photograph the cut-down trees, a strange camaraderie develops between the farmer and police. “I barely made 4,000 yuan this year [less than USD 600],” the farmer explains. “I work hard all year round to send my kid to school and we’re still eating up the family savings. The house isn’t big enough — you saw it. My dad lives in that little lean-to. An old man shouldn’t have to live like that?” The officers make sympathetic noises and say they’ll ask their captain to minimize the man’s punishment.”

“Having established this link between the officers and the peasants they police, Zhao moves to the PAP’s annual “demobilization,” which sees many of the young recruits standing down after two years on the job. Only a handful continue to an academy where they are made into PAP officers, while the rest return to civilian life in the towns and villages they came from. One of the young recruits becomes drunk after being told he will be discharged, crying bitterly as he lays bare the corruption of the system: “If I had the 50,000 yuan to pay the bribe I know I’d get into the academy,” he says to his colleague. “History is written by the victors. If you lose you’re just a loser. But if you win, even if you win by bribes or dirty tricks, you’re the winner, you’re the man.”

“Although the slim possibility of a lifetime of power and privilege is dangled in front of these young men, the majority are discarded by a system that perpetuates itself through an endless supply of eager recruits desperate to escape the impoverished conditions we’ve seen outside. There are no heroes or villains in this story, just young men caught up in a cycle that ultimately keeps most of them as powerless as the villagers they lord over.”

Zhao in his Beijing studio “From here Zhao cuts to the tethered dogs at the back of the station that we’ve seen fed throughout the film. As the smaller dog looks on, the larger animal is unceremoniously slaughtered with a knife to the heart. Only now does it become clear these animals are not guard dogs or even pets — they are raised by the police to be sacrificed for the pot. The scene is as unnerving as it is unexpected, and made all the more disturbing by the parallel with the young recruits’ fate.”

“His analogy complete, Zhao returns to the policemen’s mattresses folded in neat piles, now accompanied by the discarded insignia and caps of the demobilized recruits. As he rounds off the film’s neatly circular structure, Zhao leaves us with one final, tantalizingly open-ended image of peasants carrying household furniture across a snow-covered landscape. In the background a Christian Church dominates the scene — a sign of another power steadily growing in China’s countryside. A hint that farmers are increasingly turning to beliefs outside the morally bankrupt framework of the state. Zhao leaves us with a question rather than an answer, and an invitation to continue interrogating what we have seen after the end credits roll.”

Zhao Liang Becomes Friendly with the Chinese Government

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times: Mr. Zhao transformed his relationship with the government. In 2010 , Mr. Zhao completed “Together,” a film about discrimination against Chinese with H.I.V. and AIDS that was commissioned by the Ministry of Health. In March, Mr. Zhao dined in Hong Kong with ministry officials before walking the red carpet at a film festival. And in Beijing the next month, he accepted an award in a ceremony broadcast on state TV. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, August 13, 2011]

Mr. Zhao’s evolution from a filmmaker hounded by the government to one whom it celebrates offers a window into hard choices that face directors as they try to carve out space for self-expression in China’s authoritarian system. Like Mr. Zhao, many seek to balance their independent visions with their desires to live securely and win recognition. “When you’re working in China, there’s a gray area that you have to navigate well,” Mr. Zhao, 40, a slim man with a crew cut that is more soldier than auteur, said at his loft home in a Beijing arts district.

Yet Mr. Zhao’s compromises have damaged some of his closest friendships in China, including his one with Ai Weiwei. Mr. Zhao said that unlike Mr. Ai, he did not directly oppose the party, though his subjects, from oppressed peasants to drug-addicted rock musicians, live on China’s margins. “China no longer needs a revolution, the kind of total revolution that completely disrupts society,” he said. “The costs are too high.” Actually, in the party, there is conflict between two camps,” Mr. Zhao added, referring to friction between liberals and hard-liners. “As social intellectuals, we have to cooperate with one faction within the party to defeat the other faction.”

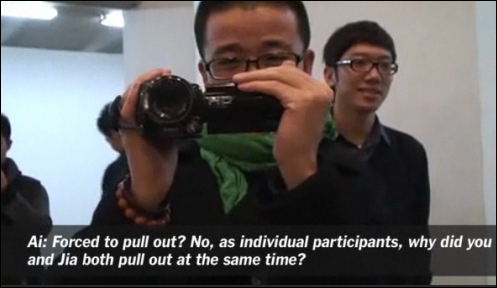

In August 2011, Zhao Liang pulled out of the Melbourne Film Festival after the Chinese government film bureau officials demanding that he and Jia Zhangke withdraw their films from the Melbourne International Film Festival to boycott a documentary on Rebiya Kadeer, the Uighur businesswoman whom China blames for unrest in the Xinjiang region. The two directors decided to pull out. “You’re a small figure, it’s scary, and you get stuck in a mess like this, in an international incident,” Mr. Zhao said. “Yeah, at the time I was pretty much, “Let’s think of me first.” “The bottom line, as he put it, was this: “You still need to work in this country.” Mr. Zhao was surprised to find, when returning home shortly afterward, that official news organizations had made the two filmmakers into heroes in articles and newscasts. Mr. Zhao and “Petition” were actually mentioned by name. It was an upturn in Mr. Zhao’s relationship with the government, but not one he entirely welcomed. “I sort of felt like I had been used,” he said. In October 2011, at an art exhibition opening in Beijing, Ai Weiwei challenged Mr. Zhao to defend his decision to boycott Melbourne. Mr. Ai recorded the encounter on video and posted it online. Mr. Zhao looked anguished at being ambushed by his friend. ‘so did you receive any financing afterwards from the state?” Mr. Ai asked. “I heard you did.” “Of course I didn’t, Ai Weiwei,” Mr. Zhao said.

scene from Together

Together

Zhao made the film “Together”, documentary about the real roles of six HIV-positive people, to go with Gu Changwei's “Love for Life” — a film about AIDS with Zhang Ziyi and Aaron Kwok. Liu Wei wrote in the China Daily, “Gu invited the HIV-positive crew members to make the film more convincing, and to emphasize his team's anti-discriminatory attitude to those afflicted with the disease. Before filming, Gu's wife Jiang Wenli, who also stars in the film, suggested he make a documentary at the same time. Jiang has worked as an ambassador for AIDS prevention for eight years.” [Source: Liu Wei , China Daily, December 9, 2010]

“It was a tough task, however, for director Zhao Liang, who directed the documentary under Gu's supervision, to find six HIV-positive people who were willing to be filmed. Zhao started with online communities for the group. He talked to them and won their trust before making the invitation. Still, most of them refused him. "My mother would collapse if she saw me on the screen," one HIV-positive person told Zhao. "Nobody will talk to me if they know I am an HIV carrier," said another.”

“Zhao talked to about 60 AIDS patients before six finally agreed to work on the set, or star in the film. Even so, half of them insisted their faces were covered. Among the three who did agree to have their faces shown was 12-year-old Hu Zetao, a student at Red Ribbon School, an institute for 16 children with AIDS in Shanxi province. Hu's mother died of AIDS when he was 4. He lives with his father and stepmother. When Gu's crew went to Hu's home, they found the family ate separately from the boy. After they finished the meal, he washed his bowl alone.”

“The scene was captured in “Together”. Gu told Hu to recall his experiences of being bullied by people and cry as loudly as he could. He immediately did so and could not stop for many minutes. Hu's teacher Liu Qian worked on the set, too, taking care of the child. Liu has been HIV-positive for 10 years, after an illegal blood transfusion. To her 16 students, the pretty woman is like a loving mother.”

“The middle-aged Xia, from Shanghai will not reveal how he got the disease. He was the actors' stand-in to test the lighting. Xia's biggest dream is to find a stable job in Shanghai. Presently, he cannot even find a place to get his hair cut, as barbers know he has the disease and refuse his custom. Xia had to leave the set prematurely because he became ill. Before he left he went to every crew and cast member to say goodbye, including Zhang and Kwok.”

“After three months of shooting, Hu Zetao's family now eat with him. Liu works at the school, taking care of her children, while Xia is still looking for a job. Living with HIV-positive people affected the crew. At the beginning of the documentary, one crew member was too scared to open his mouth when he knew he was sitting beside an HIV patient. At the film's end he said he now knows the importance of respect. Not all were equally courageous, though. Two crew members quit the film when they knew HIV carriers were working with them. Jiang Wenli and other actors tried to build trust between the team members. Zhang Ziyi's niece and Jiang's

Zhao Liang screen-shot

Government Support of Together

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times “Together,” which was submitted to censors, avoids mentioning the government’s long cover-up of H.I.V. and AIDS in China. And Mr. Zhao was asked by officials to make a number of cuts. One Chinese film expert, after watching “Together” in Hong Kong, said Mr. Zhao had “gone to the other side.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, August 13, 2011]

The movie has been shown in Chinese theaters and at a few prestigious international festivals, with official support. Mr. Zhao, like many artists who have chosen this path, sees his decision to work within the system in practical terms. “I think that a work has to have an audience,” he said. “The meaning of a piece of work has to be acknowledged by other people. It has to influence other people.”

Karin Chien, founder of dGenerate Films, told the New York Times Mr. Zhao’s decision to make “Together” surprised her. But she said the move was similar to the way American directors sometimes jumped between independent and studio productions. “In any industry, there’s an appeal for someone who wants to effect change to work within the system and see if that creates more change,” she said. Zhu Rikun, an organizer of an independent film festival, said “Together” addressed “a very important subject,” but insisted that “a film that has anything to do with an official or with the government cannot have a good result, so it’s absolutely hopeless.”

Zhao Liang’s Behemoth

Zhao Liang's film Behemoth (2015) was filmed in Inner Mongolia. According to Vimeo: Zhao Liang draws inspiration from Dante's Inferno for this simultaneously intoxicating and terrifying glimpse at the ravages wrought upon Inner Mongolia by its coal and iron industries. A poetic voiceover speaks of the insatiability of desire on top of stunning images of landscapes (and their decimation), machines (and their spectacular functions), and people (and the toll of their labor). Interspersed are sublime tableaux of a prone nude body — asleep? just born? dead? — posed against a refracted horizon. A wholly absorbing guided tour of exploding hillsides, dank mine shafts, cacophonous factories, and vacant cities, Behemoth builds upon Zhao’s previous exposés by combining his muckraking streak with a painterly vision of a social and ecological nightmare otherwise unfolding out of sight, out of mind.

Alex Subler wrote in Slant Magazine: “Behemoth” “blurs the lines between video art and documentary, visually exploring multiple open-pit coal mines in the sparse hinterlands of China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The film forgoes the spoken word completely. It stylistically melds poetry and performance art to portray the lives of various coal miners and iron smelters as they struggle to produce raw material fast enough for China's ever-growing economy. The largely plotless film draws one in through the sheer juxtaposition of its monstrous, inhuman-sized landscapes and the intimate close-ups of miners' soot-covered faces. Though banned from being screened inside China, the film was shown to a packed house in an underground screening room on the outskirts of Beijing. [Source: Alex Subler, Slant Magazine, Translation by Yasi Xu and Xuanzi Zhang, March 16, 2016]

Zhao told Slant magazine: It took me over three years to prepare for this film. At first it was a lot of location scouting. I wandered around many places in China, and I had two themes in mind. One was environmental, and the other was about pneumatosis [black lung disease]...There are actually more than a few large coal mines in the south, but I was more moved by the ones that I saw in Inner Mongolia. It's hard to imagine. The coal mines in Inner Mongolia look like they're from outer space. It's such a visual stimulation. I think many Chinese people don't have the opportunity to see these things. That's where I found all the elements that I wanted for the film. Although the pollution in the Yangtze River is rather serious, it's more difficult to present it through visuals. You can only really rely on data and interviews [to communicate that], but I don't do films in that fashion.

“At the beginning of the production I was using a more conventional documentary style, but I'm also a video artist. Video art is very free, unlike documentary, which tends to have a linear logic. You shoot a scene and, if you like it, you can shoot for as long as you want. No one will say that you're wrong even if you turn your camera sideways. So when I started shooting the raw materials, I shot freely as if making video art. During the production, I exhibited some of the footage at the Shanghai Biennial and at a gallery in Beijing. A lot of it was appearing as installation art. Then, while I was editing the film, I realized I had a lot of faces and a lot of still shots — and that if I had used all these materials to make a conventional documentary, it would have been a pity. So I decided to add more elements of modern art to my documentary.

scene from Together

Hu Jie

Ian Johnson wrote in New York Review of Books: “Though none of his works have been publicly shown in China, Hu Jie is one of his country’s most noteworthy filmmakers. He is best known for his trilogy of documentaries about Maoist China, which includes “Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul” (2004), telling the now-legendary story of a young Christian woman who died in prison for refusing to recant her criticisms of the Party during the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957; “Though I Am Gone” (2007), about a teacher who was beaten to death by her own students at the outset of the Cultural Revolution in 1966; and “Spark” (2013), describing a doomed underground publication in 1960 that tried to expose the Great Leap famine, which killed upward of 30 million people. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, May 27, 2015]

In a letter to 2012 film festival in Kathmandu, Nepal on Chinese documentaries organized by Film Southasia and curated by La Frances Hui of the Asia Society, Hu Jie wrote: I am not a professional filmmaker. I was once an air force captain, and I had studied at an art academy. I could have become a painter because I love painting. But when I saw human sufferings and the painful past and present, I kept asking myself: What is art? What is my relationship with art? [Source: dGenerate Films, August 14, 2012]

Once I acquired a very simple family-style video camera. I began to use it to film things happening around me. I realized that this was the artistic medium between me and reality. Later, I used this little camera to enter a not so distant past. I pushed open a door that had previously sealed off history. Behind that door are victims’ corpses, cries and sobs, blood and hidden truths. I need courage, which I have being a 15-year army veteran. I also have health. I also need an independent mind. I need to know that where I live, there was this history. I am an artist. I need to investigate, document, preserve, and share.

On his experience in the Cultural Revolution, Hu Jie said: , The schools were closed at first and then when they reopened we learned nothing. The days were filled with struggle session, demonstrations, criticism meets, and things like that. Our family class background wasn’t very good so my mother very often had to go out to give self-criticisms. She was a doctor and had to go to factories and treat patients and only got back home very late. She didn’t really look after us. My father was a soldier and he wasn’t at home. I had to take care of a lot of things because I was the oldest. I had to care for my two younger sisters. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, May 27, 2015]

Hu’s education only restarted around middle school. We didn’t really learn anything. People of my generation, we basically didn’t learn anything at school. On the other hand, I learned to struggle. When I was young I had to raise chickens, geese, sheep — even though we were in the city. It was the only way to get a bit of money. I learned to take care of myself. Boys fought a lot and I often ended up with a bloody nose and a swollen face.

Spark (sometimes translated as “Glowing Embers”) won top prize at the 2014 Taiwan Independent Documentary Festival. It deals with a magazine formed by four students who tried to document the famine that they saw happening around them during the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s. They only managed to produce a few copies before being arrested. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, May 27, 2015]

Hu Jie on Becoming a Fimlmaker

On how he became become interested in film and art, Hu Jie said: I went to the People’s Liberation Army Arts College in Beijing from 1989 to 1991. It had a huge impact on me because I got to know Beijing’s art scene and how art can express social problems. It was just after June 4 and society was gloomy. No one spoke too openly. But by meeting these artists, I got to exchange ideas, and learn new things. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, May 27, 2015]

Hu left the PLA in 1992 and wandered around China. He lived in the Old Summer Palace and began to film. He said: “Not too many people were making documentary films then. In fact, almost no one. Back then, you couldn’t even find a book on how to make documentary films. I felt that the problems in society were so serious, but the media was just broadcasting propaganda. There was such a gap. I thought then: Why don’t those journalists tell the truth? Then I thought: Why don’t you try yourself, try to say something true? A friend who had returned from Japan had a Super 8 camera and I bought it. So I left with a camera and traveled. I went to Qinghai. I went to mines. I made a lot of films. Everything was at the grassroots. I stayed with people so poor they had nothing.

On his time woring for Xinhua, the state news agency, Hu said: It was an interesting job. I was hired to make short documentary films. You could film corrupt officials. They would have just been arrested and you could go to the prison and interview them. They’d open their hearts to you, crying and weeping. Once I was sent to a village to interview a village chief. The village party secretary was beaten up by thugs and told to follow their orders. You saw things like that. But then I think they knew I was filming other things on my own, and I was asked to leave. That was because of the Lin Zhao film? I never let anyone know that I was filming the story. Working at Xinhua, I knew how the government likes to keep secrets, and doesn’t want ordinary people to know about this sort of thing. But I felt it was too important. In China at that time, no one dared say anything, but one person did. Everyone was scared of death but one person wasn’t scared to die. While I was making the Lin Zhao film, and interviewing people, I felt that the history I had learned, that I didn’t know it. How difficult has it been to work as a documentary filmmaker? I never take money from anyone, especially not from overseas. I win some money from awards. The police are very clear on this. Don’t take others’ money. But the police know everything. They know your every move. They call me and say “Teacher Hu, where are you going? We can drive you there.” They sometimes call ahead and tell people not to meet me.

"Though I Am Gone"

“Though I Am Gone” (Wo Sui Si Qu) (2007, Hu Jie second film, concerns the death of Bian Zhongyun, the principal at Beijing Normal University Girls High School, one of China's most prestigious girls' high schoo, and mother of four. On August 5, 1966, Bian collapsed on the school campus after being beaten to death. Hu interviews Bian's husband Wang Jingyao, who bought a camera and took pictures right before her cremation, revealing her bruised body. The elderly man in his 80s speaks about his wife's death with frankness and emotion. "Bian was the earliest victim of a student beating in Beijing. I photographed the film from a different angle: a husband who used to be a supporter of violent revolution rethinks his ideas," Hu said. The film cannot be shown in China but may be found on YouTube

Chris Berry, a professor at Kings College, London, wrote: This is an exceptional achievement because it combines remarkable testimony with a self-reflexive meditation on documentary. Hu pioneered the trend for politically sensitive oral history films. Here, he interviews the husband of Bian Zhongyun, principal of a Beijing middle school beaten to death during the Cultural Revolution by her own students. Told his wife was dying in hospital, he grabbed his camera. Hu’s film not only interrogates the Cultural Revolution, but also the compulsion and need to witness, document, and record. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

“Though I am Gone” and the account of what happened to Bian is largely based on interviews with her husband who at the time with exceptional courage took photographs of her corpse and the circumstances of her death. . Bian was one of the earliest victims of the Cultural Revolution. Tristan Shaw wrote in Listverse: “In June 1966, some of the school’s students began to criticize school officials and organize revolutionary meetings. Bian’s college degree and bourgeois background made her a natural target for the revolutionaries, although many of them were ironically from privileged families themselves. Over the next two months, Bian was repeatedly harassed by her students and even beaten during a meeting. On August 4 of that summer, Bian was tortured and warned not to come to school the next day. But she decided to come in that morning anyway. It was a courageous decision that would cost Bian her life. First, her teenage students beat and kicked her. Then they whacked her with nailed-filled table legs. The attack was so terrible that Bian soiled herself and was knocked unconscious before dying of her wounds. Nobody was ever punished for her murder, and even today, the perpetrators have yet to step forward. [Source: Tristan Shaw, Listverse, June 24, 2016 -]

Berry said" Bian's widower "testifies about what happened and how no one has ever been brought to justice, despite his best efforts. Furthermore, he shows how he has carefully kept all the evidence he can. So, the film not only gives him the voice and deals with a crucial issue off-limits to mainstream media. It also turns into a contemplation of the ongoing drive to confront reality and why it continues to be so important in China today. To me, this clip sums up the three aspects of “confronting reality” that I have been trying to draw to your attention today: first, a profound questioning of what reality is, how we can perceive it and how we should represent it; second, a proliferation of styles and ways of employing the “on-the-spot” materials that are now dominant and taken for granted; and, finally, a deep concern about who gets to make these films and whose voice gets to be recorded. [Source: Chris Berry, professor at Kings College, London, dGenerate Films, November 14, 2013]

See Separate Article PROMINENT VICTIMS OF CULTURAL REVOLUTION ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul

“Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul” (Xun Zhao Lin Zhao De Ling Hun) directed by Hu Jie (2004) is a gripping story about Lin Zhao, a young woman who attended Peking University in the 1950s. Of all the students at the university, she was the only one who refused to write a political confession during Mao’s Anti-Rightist Campaign, and as a result was sentenced to prison. Lin composed endless articles and poems from her cell. Forbidden to use pens, she wrote with a hairpin dipped in her own blood. Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul stands as a landmark in the Chinese independent documentary movement. The result is a lasting testament to a young woman’s legacy of courage and conviction.

La Frances Hui of the Asia Society wrote: The most fearless of all independent filmmakers, Hu Jie tackles some of the most taboo subjects in China. This film documents the life of a bright Beijing University student Lin Zhao (1932-68), who was banished during the anti-rightist movement for her outspokenness. In jail, Lin continued her defiance and wrote critical commentary aiming at Mao Zedong on prison walls and any scraps of paper she could find using her own blood. Lin died tragically and forgotten during imprisonment. “Yingjin Zhang, a Professor of Chinese Literature at University of California, San Diego, wrote: This audacious, heart-wrenching work challenges a culture of indoctrination and oblivion by investigating a case of political persecution in the early decades of the PRC. By retrieving writings done with the victim’s own blood and interviewing her former acquaintances, the film demonstrates that the past is not forgotten and justice still awaits redress in China. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

Ting Guo wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books: “On May 31, 1965, 33-year-old Lin Zhao was tried in Shanghai and sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment. She was charged as the lead member of a counter-revolutionary clique that had published an underground journal decrying communist misrule and Mao’s Great Leap Forward, a collectivization campaign that caused an unprecedented famine and claimed at least 36 million lives between 1959 and 1961. “This is a shameful ruling!” Lin Zhao wrote on the back of the verdict the next day, in her own blood. Three years later, she was executed by firing squad under specific instructions from Chairman Mao himself.[Source: Ting Guo, Los Angeles Review of Books, China Channel, May 19, 2019]

“Lin Zhao’s father committed suicide a month after Lin’s arrest, and her mother died a while after her execution. In Shanghai, where I grew up and where Lin was tried, imprisoned and killed, the story (the sort told only in private) goes that Lin’s mother was asked to pay for the bullets that killed her daughter. It is also said (in private) that in the years that followed, at the Bund, the former International Settlement on the Huangpu River, one could see Lin’s mother crying and asking for Lin’s return.

“Throughout Lin’s imprisonment, where she was subjected to extreme torture, she wrote thousands of letters and essays in her own blood. Those letters are now kept at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace at Stanford University. Lin’s story has and continues to touch and change lives. Gan Cui, Lin’s fiancé, spent four months hand-copying Lin’s blood letters when they first became available to Lin’s siblings, her only remaining family. These hand-copied documents later provided the historical and autobiographical material for Hu Jie, the director of the 2004 documentary Searching for Lin Zhao’s Soul, who quit his job and used his personal savings to make the documentary.

See Separate Article PROMINENT VICTIMS OF CULTURAL REVOLUTION ATTACKS factsanddetails.com

Wang Bing

Wang Bing made a widely acclaimed series of feature documentaries. “The Ditch” (Jiabiangou) is Wang’s first feature film. He has made a fiction short “Brutality Factory” (Baonüe gongchang, 2007) as well as the widely acclaimed nine-hour "West of the Tracks". James Richard Havis wrote in the South China Morning Post: Capturing life as it happens, and recording life as it happened, could be the twin mantras of Chinese documentary filmmaker Wang Bing. Since his epic nine-hour 2002 documentary “Tie Xi Qu” (“West of the Tracks”), which followed the lives of workers in the decaying state-run factories of China’s rust belt northeast, 51-year-old Wang has become one of China’s most important filmmakers, and earned an international reputation. Wang, whose films are not screened in China because of their controversial political and social subject matter, was the subject of an all-encompassing retrospective in New York in 2018, hosted by three prestigious venues and institutions: The Metrograph, the Film Society of Lincoln Centre, and the Asia Society in an event put together by the Beijing Contemporary Art Foundation. [Source: James Richard Havis, South China Morning Post, November 27, 2018]

“His camera probes far and wide, covering a range of issues, historical and social. He films his subjects over a long period of time, capturing the minutiae of their daily existence — their conversations, their family relationships, their mealtime habits, their daily work, and their friendships. What emerges is a substantial portrait of his subjects’ hopes, fears, problems, and, inevitably, their overarching relationship with the state. Wang says he has no agenda, and simply films subjects that interest him — for instance, “Three Sisters”, which documents the lives of three children who have been left to fend for themselves since their parents left their village to find work, came about after a chance meeting. But he notes that the aim of his work is to record the bits of Chinese life that exist below the radar of most media, and to document historical events that have been expunged from the record by the government.

“Wang also made his only feature film, “The Ditch”, as well as He Fengming, a 2006 documentary, about Jiabiangou (a labor camp used in the Anti-Rightist movement in China in the 1950s) "Til Madness Do Us Part” is a bleak, challenging documentary about life in a grim mental asylum in southwest China — the only respite comes when an inmate is suddenly released — while “Ta’ang” details the forced migration of the Ta’ang (Da’ang) ethnic minority who live along the border between Myanmar and China. “The most important thing is that future generations, and society as a whole, have enough material, enough information, to find out what really happened in the past,” Wang tells the Post in an interview in New York. The fact that most people in China are not able to see his films — although some have been available in pirated form — does not concern him unduly. “I don’t consider whether the films will serve certain functions when I’m making them, so I don’t think about whether my films will foster a change in society. It’s hard for us to imagine what the future will bring, and history as a force will sometimes behave or unfold in a way that is unexpected and unpredictable. The most important thing is that I am making the film that I want to make, and telling a story that I think needs to be told,” he says.

“The roots of his creativity are varied. Born in Xian, western China, Wang started working in a construction design studio when he was 14 — his father was a civil engineer who was killed in gas poisoning accident — where he learned about architecture, something which sparked an interest in the arts. He went on to study photography at the Lu Xun Academy of Fine Arts in Shenyang, northeast China, quite a prestigious institution. This led to further studies in cinematography at the Beijing Film Academy.

“He says he watched many films of all types at the academy, and still thinks it’s important to watch the works of others. Cinema, which is only just over a century old, is a somewhat immature medium compared to fine art, he thinks, and Chinese cinema has been especially constrained since 1949. “It’s very important for filmmakers to try and change the attitude of viewers toward film, and to change their perception of what cinema is,” he says. “We should not only care about the characters, the subjects, and the narrative of the story. We should also take note of the aesthetics — we should offer the audience as many options, as many alternatives, as many possibilities of cinema as we can.”

His view in part results from his belief that Chinese cinema since 1949 has been heavily influenced by the Russian socialist-realist model, in terms of both style and theory. (Wang does not agree, for instance, that China’s so-called Fifth Generation filmmakers attempted to break free from that model in terms of style and content.) The Chinese studio system is simply about manufacturing propaganda,” Wang says. “It is crucial, especially in the context of China, to tell audiences that film culture is not limited to that kind of propaganda, to that kind of political film. There many ways to present films, many ways to make films, and many different possibilities to explore within cinematic culture. We should make the audience aware of that.” Documentaries, Wang notes, are low-key projects which can be shot alone, or with a crew of two or three, and that’s meant he’s been able to carry out filming without interference from the authorities so far. Although feature films are heavily regulated by the authorities starting from the script stage, documentaries are not, so they exist under the radar. But China’s increasing censorship of the media, including its recent focus on digital media, may change all that. Wang does not want to comment on this issue,

The Ditch

Wang Bing’s “The Ditch” (“Jiabiangou”, 2010 ) — a film about human suffering at a re-education camp in the windswept Gobi Desert — premiered at the Venice Film Festival as the ‘surprise film’ in the competition. Set in 1960, the film chronicles the conditions facing inmates accused of being right-wing dissidents opposed to China's great socialist experiment, condemned to digging a ditch hundreds of miles long in the dead of winter. Famine stalks the camp, and soon death is a daily fact. “The Ditch” is a thoroughly independent drama, filmed in Inner Mongolia, with post-production in France and Belgium. “The Ditch” won three awards at Las Palmas de Gran Canaria International Film Festival, including Jury Special Award, Audience Award and Signis Award. Wang told AFP, “It's a film that brings dignity to those who suffered and not a “denunciation film or a protest film.” “We wanted to preserve the memories, be aware of the memories, even painful ones.” As Wang was born in 1967, the events “took place before my birth, so I put in great effort to understand the 1950s and 1960s in China, to understand the historical truth.”

Shelly Kraicer wrote in the Chinese Cinema Digest: “It opens in 1960 in the Jiabiangou reeducation camp, when a new batch of condemned “rightists” arrives to exhaust themselves digging ditches and most likely starve to death on severely restricted rations. Entirely based, according to Wang, on testimony from former camp inmates whom he has interviewed and whose published accounts he read, the film focuses on the day to day brutality inflicted on these men, and on their sufferings, exhaustion, and attempts (sometimes successful) to avoid dying of starvation.” [Source: Shelly Kraicer, Chinese Cinema Digest]

“The film shows unrelentingly misery. The details of The Ditch are striking, sometimes very near sickening to watch (he spares the audience very little), and add up to one of the bleakest, darkest films I’ve seen on this subject. Men die in their beds as a matter of course ; numb routines (once work is suspended because of the severe food shortage) consist of seeing who dies and attending to the bodies. The inmates, barely differentiated by the darkness of the setting and by Wang’s distant camera, mostly sit passively, and occasionally face ridiculous political attacks. Sometimes vermin are trapped, to be eaten. Two dramatic incidents mark the second half of the film: an escape attempt, ambiguously resolved, and the appearance of the grieving wife of one of the dead inmates. Her story closely matches, in many details, the factual narrative of He Fengming, the subject of Wang’s second monumental documentary Fengming: a Chinese Memoir (He Fengming, 2006).”

Justin Chang wrote in Variety of “The Ditch” : “this powerful realist treatment offers a brutally prolonged immersion in the labor camps where numerous so-called dissidents were sent in the late 1950s. Result makes for blunt, arduous but gripping viewing that will be in demand at festivals, particularly human-rights events, and in broadcast play.” Wang Bing’s previous efforts are “Fengming: A Chinese Memoir”, his three-hour epic documentary about China's “anti-rightist” campaign, and nine-hour “West of the Tracks”. [Source: Justin Chang, Variety]

“”The Ditch” makes only glancing reference to the political events that precipitated the anti-rightist movement, and the film's minimal context and thinly sketched characters could be read as a broad condemnation of atrocities and abuses perpetrated in any country... Set over a three-month period in 1960, at the Mingshui annex of Jiabiangou Re-education Camp, the film observes as a new group of men arrive, are assigned to sleep in a miserable underground dugout (euphemistically described as “Dormitory 8') and begin the long, slow process of dying. The work is intense, but hunger is the prisoners' chief struggle as well as the film's main preoccupation. Rats are eaten as a matter of course, consumption of human corpses is not unheard of, and, in the most stomach-churning moment, one man happily helps himself to another's vomit. Eating seems a compulsion rather than a sign of any real will to survive, and new bodies are dragged out daily, making room for fresh arrivals.”

“Drawn from a novel by Yang Xianhui and interviews Wang conducted with survivors (one of whom, Li Xiangnian, is credited with a ‘special appearance’ as one of the prisoners), the film has an overpowering feel of unfiltered reality that persists even as tightly framed dramatic moments begin to emerge. Admirers of Wang's documentaries know his ability to capture real moments of extraordinary intimacy, and the sense of verisimilitude here is so strong that those walking in unawares may at first think they're watching another piece of highly observant reportage — never mind that no filmmaker would ever have been granted access, just as no humane documentarian could have kept the camera rolling without offering his subjects a scrap of food at the very least.”

“The film eventually comes to center on the friendship between two men, Xiao Li (Lu Ye) and Lao Dong (Yang Haoyu)... The second half is almost entirely unmodulated in its portrayal of suffering, and the illusion of realism Wang has conjured falters a bit... Dramatically, “The Ditch” is as arid and unrelenting as the setting it depicts, and its commingling of anguish and anger is far from subtle. But this may be the only way to properly dramatize and empathize with these men's experience; if barely two hours seem unendurable, three months defeat the imagination.”

West of the Tracks and Three Sisters

“West of the Tracks” (Tiexi Qu) directed by Wang Bing (2001) is nine hours long. According to Yingjin Zhang, a Professor of Chinese Literature at University of California, San Diego: It is an epic deliberation on the decline of massive industrial manufacturing in northeast China that compels the viewer to confront the ghostly ruins of giant machines and deserted factories. The soon-to-be-unemployed workers’ uncertain future evokes the nightmare rather than the glory of socialist legacy and human civilization. The slow-moving train that punctuates the film bears witness to a science fiction-like world where even the machine is abandoned in an industrial wasteland. [Source: La Frances Hui, China File, 2012]

“West of the Tracks” records social changes brought about by urbanization and “opening up” which unfolds at a pace that is both "painfully slow and brutally fast." Famed Chinese independent filmmaker Jia Zhangke wrote: The film depicts a panoramic scene of the decline of China’s state-owned factories following the failures of its planned economy. Landscapes of desolate factories and portraits of people living in difficult predicament reflect a poetic sorrow. Samantha Culp, writer, curator and producer, the film is an epic, opus and endurance test. “Wang Bing’s 9-hour documentary, about the decline of the industrial economy in and around the railways of Shenyang, is monumental in its scale but also intimate in its minute-to-minute history. To sit with this place, these people, this time, is a viewing experience like few others.

Chris Berry, a professor at Kings College, London, wrote: Wang Bing’s nine-hour elegiac epic is a strange echo of the Lumière brothers’ much shorter Leaving the Factory (1895). Instead of workers happily coming off their shifts, the three parts of "West of the Tracks" trace the death of an iconic Mao era heavy industrial zone and show people leaving forever. Smoky, snow-covered, and dark, it made me think of the Zone in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) as I sank into it and became immersed in its thoughtful nostalgia.

Translator Cindy Carter told Bruce Humes of Ethnic China: This massively ambitious 3-part opus about life in China’s rust belt changed the landscape of Chinese documentary film. Wang Bing spent 5 or 6 years of his life planning, filming, editing and perfecting this film; I spent 4 months, off and on, translating it. Everyone who worked on "West of Tracks" — from director and producers, to video techs and subtitle editors and translators, to those unnamed and intrepid individuals who volunteered their services or equipment for a few hours or days or weeks — poured their souls into the film, and it shows. Wang Bing and I have done five or six other projects since, and hopefully will continue to work together. If anyone in the world of Chinese indie film deserves the designation of “auteur”, it is Wang Bing. (Though in the world of mainstream Chinese film, the greatest auteur is Jiang Wen, hands down.) [Source: Bruce Humes, Ethnic China, May 14, 2012]

“Three Sisters” (2012) by Wang Bing moves away from the historical themes he explored in the past in masterpieces such as West of the Tracks to a subject both intimate and immediate. His camera records the lives of three extremely poor young sisters, aged ten, six, and four who live in an isolated mountainside hamlet in southwest China’s Yunnan province. Over the course of three hours without a shred of condescension or pity, the film brings us into close confrontation with the dirt, poverty, and repeatedly backbreaking daily labor these little girls are compelled to do. Big sister Ying becomes a kind of everyday hero: laborer, cook, farmer, aspiring student, and mother to her two sisters. Wang’s powerful images manage to be beautiful and seem to capture fundamental truths: we feel as if we are seeing into an essential, grassroots kind of life that hundreds of millions of Chinese people still endure every day.[Source: Shelly Kraicer, China File, January 17, 2013]

Til Madness Do Us Part

“Til Madness Do Us Part” is Wang Bing’s film about life in a Chinese mental hospital. Justin Chang wrote in Variety: There are endurance tests, and then there is Wang Bing's nearly four-hour plunge into the daily tedium and long-term despair of life in a mainland Chinese mental hospital.An unsparing chronicler of the abused and neglected in his country’s darkest corners, Chinese documentarian Wang pushes his starkly immersive strategies to a grueling yet empathetic extreme in “’Til Madness Do Us Part.” In the mental hospital, viewers patrol “the same tightly enclosed quarters in a manner that seeks to reproduce, without compromise, an inhabitant’s sense of physical, mental and spiritual entrapment. Following a few shorter, comparatively accessible outings with his 2010 drama “The Ditch” and his 2012 docu “Three Sisters,” this purposeful yet punishing work will appeal strictly to Wang’s most committed devotees on the fest and gallery circuits; bathroom breaks are advised for a film that, among other things, compels viewers to tell time by how often its subjects urinate. [Source: Justin Chang, Variety, September 13, 2013]

“For all but about 20 of its daunting 228 minutes, Wang’s documentary confines the viewer to one of the upper stories of an isolated asylum in southwest China. (Somewhat surprisingly, the director and his small crew were granted access after having been denied permission to film at a different institution near Beijing.) What we see is a painfully finite world of grimy, bare-walled rooms lining an outdoor corridor that overlooks an open courtyard below, with metal bars in place to prevent anyone from trying to climb down or jump. The building is home to about 100 men, some of whom are identified onscreen by name and length of confinement. Many have been imprisoned for as long as 10 or 12 years, a fact that comes to seem ever more unfathomable as the film stretches onward.

“With endless patience, the camera (Wang and Liu Xianhui served as lensers) roams the sometimes empty, sometimes crowded hall where the men stand around idly by day, chatting with each other or muttering to themselves, and occasionally receiving pills from the hospital staff. The filmmakers slip regularly into the men’s quarters, where they sleep about four to a room, and sometimes two to a bed. They seem barely aware of the camera’s presence, which might be a testament to Wang’s ability to foster trust and intimacy with his subjects, were it not for the fact that they don’t seem particularly aware of anything.

“This apparent obliviousness to the presence of strangers can make for uncomfortable viewing, especially when some are shown walking around naked; for all Wang’s principled efforts to lend dignity to his human subjects, these instances can’t help but raise ethical questions about the privacy these presumably mentally disturbed individuals are entitled to. If there’s a structuring motif here, it’s the recurring sight of a person casually relieving himself wherever he pleases — in a corner of the room, or on the floor outside. As a means of marking the passage of time and conveying the sheer repetitiveness of existence, it doesn’t get much more elemental.

Dead Souls

“Dead Souls” (2018) is Wang Bing’s nine -hour documentary about victims of the Maoist Anti-Rightist campaign in the 1950s. Sebastian Veg, a Professor of Chinese History in France, wrote in his blog: “Dead Souls is a project Wang Bing has been working on for over a decade. When Yang Xianhui’s book Chronicles of Jiabiangou (a collection of lightly fictionalized oral history accounts of former victims of the Anti-Rightist movementvictims of the Anti-Rightist movement in Gansu who survived the deadly famine in the Jiabiangou Reeducation Through Labor Camp in 1960), Wang Bing contacted Yang. Wang Bing is from rural Shaanxi, which borders Gansu and, as he has mentioned in interviews, two of his uncles on his father’s side were persecuted as rightists, which may have sparked his interest in the book. After buying the film rights to Yang’s book, Wang Bing proceeded to start seeking out the people Yang had talked to, conducting his own interviews with them. [Source: Sebastian Veg Blog, November 25, 2018]

One of these interviews with He Fengming, who had written a book explaining how her husband Wang Jingchao died of famine in Jiabiangou, became a stand-alone film, Fengming (2007). These interviews were preparations for a fiction film project, which was finally completed in 2010 under the title The Ditch. Shot in harrowing conditions more or less on location, it uses what I argued was a form of highly theatrical acting to create a sense of distance between the viewer and the story. Since that time, Wang Bing has mentioned that he had plans to use the footage of the 120 preparatory interviews to make a kind of compendium documentary on the Anti-Rightist movement. This is the project that has now partially come to fruition (Dead Souls is supposed to be the first part of a several-part project). Wang Bing struggled for many years with this material to the point of mental anguish and only managed to overcome the difficulties after going back to Lanzhou in 2014 and re-interviewing those of the survivors who were still alive. He has stated that observing the speed at which their ranks were thinning gave him a sense of urgency that helped him finish the film.

“Before discussing the film itself, I want to mention another unique work: Traces (2014). As Wang Bing has explained, this 29-minute documentary was shot during his first visit to the site of Jiabiangou, using old 35 mm film that he had collected for some years. During most of the film the camera points straight down to the sandy desert ground, occasionally showing the director’s boots. In the first section “Mingshui,” wherever the camera turns, it finds human bones, loosely scattered among the sand, and even several skulls, as well as some more recent remains of bottles, gourds and clothes left by vagrants. In the second section “Jiabiangou,” the camera enters some of the caves where the inmates lived in 1959-1960. “The film has a strong self-reflexive dimension. Some of the old 35 mm film is corrupt, so that geometrical shapes appear on the image.

“Dead Souls is divided into three parts (it was shown in Cannes in two parts). Of course, the main challenge in organizing the massive amount of footage (600 hours) was how to structure the film. The excellent press kit contains an interview in which Wang Bing explains that, rather than a chronological organization, he chose to give each surviving witness a block of roughly 30 minutes. Of course, this time represents only a fraction of the full interview, and Wang Bing uses exaggeratedly rough jump cuts to draw the viewers’ attention to what he is leaving out, almost like ellipsis marks in a quotation. All together, there are a dozen of these long testimonials in the film. Just like in Yang Xianhui’s book, almost all of the interviewees underscore that they had no political divergence with the communist party, they were not “rightists,” but were usually targeted for extremely minor and mundane offenses.

“While I can’t provide a full discussion of the film here, I’d like to mention two episodes that stand out very strongly. In the first part, a long sequence is devoted to the funeral of one of the survivors whom Wang Bing has briefly interviewed on his sickbed, Zhou Zhinan. A traditional burial with instruments and ritual lamentations, in the remote hilly countryside of Shaanxi (whereas the government aggressively promotes cremation as the only “modern” type of burial) in December 2005, it shows the abiding sadness and resentment of Zhou’s son who tries to lay his father to rest while honoring the memory of his persecution.

“Another outstanding episode appears in the third part of the film, with the only interview of a camp guard, Zhu Zhaonan. Wang Bing notes that guards were often older and many have already died, while others are not willing to speak out. It is also the only interview in which the director is visible. Zhu was a cook in Jiabinagou, who was sent ahead to set up the annex at Mingshui, where the greatest number of inmates ended up dying. Listening to Zhu’s narrative, suddenly all the parts of the camp’s geography and organization fall into place, as we realize how fragmented the vision of each survivor is, and how little they understood about the camp as a whole. Zhu provides fascinating details, such as the fact that in the main camp they provided halal food for Muslim rightists. He quantifies the deeply felt inequalities in treatment between cadres and inmates: cadres were given about 450g of grain per day, while the inmates’ ration was 250g. Mingshui was organized around three ditches in which the inmates lived. As everything broke down in Mingshui during the massive famine, deaths were still generally logged in the record books but the dead could no longer be buried because the ground was frozen at least one meter deep. Death was everywhere and became completely normal. The authorities wanted the rightists dead: “ .

“Sympathizing with the rightists was out of the question because of “class consciousness,” even though many of the guards knew that they had been falsely accused or deported on trumped-up charges. Zhu prides himself on having at least tried not to mishandle anyone. The interview ends with the only known surviving photo of Jiabiangou, which Zhu gave to Wang Bing when they met again. It shows him riding a bicycle smiling amid a bunch of bedraggled inmates, and is a truly chilling testimonial to what in effect became a death camp, reminiscent of controversies surrounding photos of Nazi concentration camps. This is underscored in the ending of the film, which concludes with the footage of the camera nosing among the bones scattered in the sand.

Image Sources: dGenerate Films, YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021