REPRESSION AFTER THE TIBETAN REVOLT IN 1959

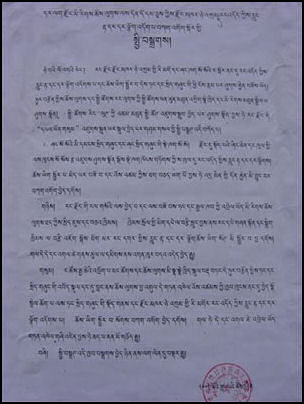

Notice banning prayer flags in Darlag

After the 1959 revolt, Beijing set about trying to wipe out Tibetan culture and make Tibet into a Marxist state. Lamas and noblemen were forced to work at menial jobs and attend struggle sessions. Resisters were brutally tortured and punished. Under Mao's command to "make grain the key link" Tibetan farmers were forced abandon raising traditional crops such as barley and grow crops like rice and wheat that were unsuited for high-altitude agriculture. Tens of thousands are believed to have died from starvation.

Robert A. F. Thurman wrote in the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity: “In 1949 the People's Republic of China began invading, occupying, and colonizing Tibet. China entered into Tibet immediately after the communist victory over the Chinese Nationalists, imposed a treaty of "liberation" on the Tibetans, militarily occupied Tibet's territory, and divided that territory into twelve administrative units. It forcibly repressed Tibetan resistance between 1956 and 1959 and annexed Tibet in 1965. Since then it has engaged in massive colonization of all parts of Tibet. For its part, China claims that Tibet has always been a part of China, that a Tibetan person is a type of Chinese person, and that, therefore, all of the above is an internal affair of the Chinese people. The Chinese government has thus sought to overcome the geographical difference with industrial technology, erase and rewrite Tibet's history, destroy Tibet's language, suppress the culture, eradicate the religion (a priority of communist ideology in general), and replace the Tibetan people with Chinese people. [Source: Robert A. F. Thurman, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

Attempts to reign in the Tibetans were not unique to the Communists. Chiang Kai-shek declared in the 1946 that Tibetans were Chinese, and it is unlikely that he would have allowed Tibetan independence if the Nationalists had won the civil war.

See Separate Articles: CHINESE INVASION OF TIBET IN 1950 AND ITS AFTERMATH factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN REVOLT IN 1959 AND THE CHINESE TAKEOVER OF TIBET factsanddetails.com ; SECRET CIA WAR IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ; STORY OF A MILITANT TIBETAN MONK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947" by Tsering Shakya Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, volume 2: The Calm before the Storm: 1951-1955" by Melvyn C. Goldstein Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 3: The Storm Clouds Descend, 1955–1957" by Melvyn C. Goldstein Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 4: In the Eye of the Storm, 1957-1959" by Melvyn C. Goldstein | Amazon.com; “Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959" by Jianglin Li and Susan Wilf Amazon.com; “When the Iron Bird Flies: China's Secret War in Tibet” by Jianglin Li and Dalai Lama Amazon.com; “Flight of the Bön Monks: War, Persecution, and the Salvation of Tibet's Oldest Religion” by Harvey Rice , Jackie Cole , et al. Amazon.com; “The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering” by Melvyn C. Goldstein , William R Siebenschuh, et al. Amazon.com; “A Poisoned Arrow: the Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama” By Bskal-Bzan-Tshe-Brtan Amazon.com; General History: “Tibet: A History” by Sam van Schaik Amazon.com; “A Historical Atlas of Tibet” by Karl E. Ryavec Amazon.com; “Histories of Tibet” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer , William A. McGrath, Amazon.com; “Himalaya: A Human History” by Ed Douglas, James Cameron Stewart, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet & Its History” by Hugh Richardson (1989) Amazon.com; "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein Amazon.com; “The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama” by Thomas Laird Amazon.com

Religious Repression by the Chinese in Tibet

As part of "Religious Reforms" Buddhist rituals were banned, temples were turned into pigsties, Buddhist statues were beheaded, alters were melted down for their gold, ancient manuscripts were used for toilet paper, monasteries were blown up, and monks were executed or sent to work in factories or labor camps. The Great Monetary of Drepung in Lhasa was turned into Guesthouse Number Five and the medical college of Mendzekhan on Chakpori Hill was torn down and replaced with a television antennae. Defrocked monks were sent to work on communes and build power stations.

Before the Chinese takeover there were 6,259 monasteries with 592,000 monks and nuns. In 1959, there were over 1,600 working monasteries in Tibet. By 1979, there were only 10. Beginning in 1965 Tibet was administered by the Chinese government as the Tibet Autonomous Region. Historian Ian Buruma wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Religion was crushed in name of Marxist secularism...Nomads were forced onto concrete settlements...Tibetan art was 'frozen into folklore emblems of the officially promoted “minority culture.”...Such destruction was not unique to Tibet. The wrecking of tradition and forced cultural regimentation took place everywhere in China. In some respects the Tibetans were treated less ruthlessly that the majority of Chinese.”

The destruction of religious sites in greater Tibet began outside the Tibet Autonomous Region in Kham (Eastern Tibet) in 1956, under the guise of suppressing local uprisings in Gansu, Qinghai, Yunnan and Sichuan. The Tibet Mirror supplied the first and most detailed Tibetan news of events in Kham and the destruction of the monasteries there. (Carole McGrahanan: Arrested Histories, 243.) The first drawings of the destruction of monasteries appeared in November 1956. The Panchen Lama wrote: “Our Han cadres produced a plan, our Tibetan cadres mobilized, and some people among the activists who did not understand reason played the part of executors of the plan. They usurped the name of the masses, they put on the mask [mianju] of the masses, and stirred up a great flood of waves to eliminate statues of the Buddha, scriptures and stupas [reliquaries]. They burned countless statues of the Buddha, scriptures and stupas, threw them into the water, threw them onto the ground, broke them and melted them. Recklessly, they carried out a wild and hasty [fengxiang chuangru] destruction of monasteries, halls, "mani" walls and stupas, and stole many ornaments from the statues and precious things from the stupas.” [Image and information taken from Isrun Engelhardt – Tharchin’s One Man War with Mao [PDF], p. 190.) [Source: buddhism-controversy-blog.com, April 21, 2013]

Repression, Death and Violence in Tibet

The Tibetan government in exile has estimated that 1.2 million Tibetans (more than one sixth of all Tibetans) have died under Communist rule as a result of war, starvation and repression since 1950. The Chinese admit to killing 87,000 Tibetans. The Dalai Lama believes that about 200,000 have died. According to one Chinese official between 10 and 15 percent of the Tibetan population (400,000 to 600,000 people) were imprisoned after the 1959 uprising, and about 40 percent of these Tibetans died while in prison. Tenzin Choedrak, the Dalai Lama's physician, said that half the prisoners in the labor camp where he was kept for two years, died of starvation. Some scholars believe that as many as 90 percent of all prisoners died while in prison. [Source: Washington Post, July 17, 1994]

Robert A. F. Thurman wrote in the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity: “In China itself, communist leader Mao Zedong's policies caused the death of as many as 60 million Chinese people by war, famine, class struggle, and forced labor in thought-reform labor camps. As many as 1.2 million deaths in Tibet resulted from the same policies, as well as lethal agricultural mismanagement, collectivization, class struggle, cultural destruction, and forced sterilization. However, in the case of Tibet, the special long-term imperative of attempting to remove evidence against and provide justification for the Chinese claim of long-term ownership of the land, its resources, and its people gave these policies an additional edge. [Source: Robert A. F. Thurman, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

“In 1960 the nongovernmental International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) gave a report titled Tibet and the Chinese People's Republic to the United Nations. The report was prepared by the ICJ's Legal Inquiry Committee, composed of eleven international lawyers from around the world. This report accused the Chinese of the crime of genocide in Tibet, after nine years of full occupation, six years before the devastation of the cultural revolution began. The Commission was careful to state that the "genocide" was directed against the Tibetans as a religious group, rather than a racial, "ethnical," or national group. |~|

“The report's conclusions reflect the uncertainty felt at that time about Tibetans being a distinct race, ethnicity, or nation. The Commission did state that it considered Tibet a de facto independent state at least from 1913 until 1950. However, the Chinese themselves perceive the Tibetans in terms of race, ethnicity, and even nation. In the Chinese constitution, "national minorities" have certain protections on paper, and smaller minorities living in areas where ethnic Chinese constitute the vast majority of the population receive some of these protections. |~|

Theroux wrote that Tibet has been subjected to "bombings, massacres, executions for 'economic sabotage,' oppressive nagging, crucifixions, tortures, desecrations, idiotic slogans, political songs, humiliations, edicts, insults, racism, baggy pants, army uniforms, brass bands, bad food, and pink socks. Despite all this it seems the former nation has hardly been affected."

Religious Repression in Tibet, See Religion, Tibet; Human Rights, Government, Tibet

Panchen Lama’s Report on Tibet After the Chinese Takeover

In 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama presented the Chinese Communist Party with report on the conditions in Tibet in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The document was not well received. Mao Zedong called it "a poisoned arrow shot at the Party by reactionary feudal overlords". [Source: The Tibet Information Network (TIN) document “Poisoned Arrow. The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama“ (1997). It quotes from the “Petition of 70,000 characters” by the young 10th Panchen Lama, from subliminal.org \~/]

The 10th Panchen Lama’s report was presented to China's Premier, Zhou Enlai in May, 1962. For some three months Li Weihan, head of China's United Front Department, took initial steps to implement the report's suggestions, but in August that year Mao called for the resumption of class struggle and in October Li was criticised for his links with the Panchen Lama. In the same month the Panchen Lama was ordered to undertake a self criticism, and a year later was subjected to a 50 day long struggle session in Lhasa before being sent to Beijing, where he spent 14 of the following 15 years in detention or under virtual house arrest. The Panchen Lama was fully rehabilitated only in 1988, the year before he died. His report, known as "the 70,000 Character Petition", remained secret for three and half decades. \~/

The 120 page document, divided into eight sections, gives details of the situation in all Tibetan-inhabited areas after inspection tours there by the Panchen Lama in 1961 and early 1962. One of its major criticisms was the excessive punishment imposed by the authorities to avenge the 1959 Uprising in Tibet. "We have no way of knowing how many have been arrested. In each area 10,000 or more have been arrested. Good and bad, innocent or guilty, they have all been arrested, contrary to any legal system that exists anywhere in the world. ... In some areas the majority of men have been arrested and jailed so that most of the work is done by women, old people and children," says the report. \~/

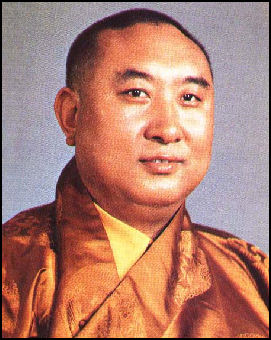

10th Panchen Lama It alleges that there was a policy of collective punishment, by which Tibetans had been executed because their relatives were involved in the uprising, and it accuses officials of deliberately subjecting political prisoners to harsh conditions so that they would die. "Even family members of the rebels were ordered to be killed. ... Officials deliberately put people in jail under conditions which they are not used to so that there were a large number of abnormal deaths", it says. \~/

The Panchen Lama expresses in his petition concerns that Chinese policies were threatening the survival of the Tibetans as a nationality. "The population of Tibet has been seriously reduced. Not only is this damaging to the prosperity of the Tibetan race but it poses a grave danger to the very existence of the Tibetan race and could even push the Tibetans to the last breath," he wrote, in a passage said to have been expressly rejected by Zhou Enlai. \~/

The Panchen Lama had been encouraged to write his report by Li Weihan, of the United Front, who reported directly to Deng Xiaoping and who may have hoped to use it to mobilise support against ultra-leftists throughout China. But other Tibetan leaders, including Ngapo Ngawang Jigme, had pleaded with the Panchen Lama not to submit it in writing, according to a biography published in Beijing by the Tibetologist Jamphel Gyatso in 1989. The Panchen Lama, who was only 24 years old at the time, was not a Party member and faced considerable risks, especially since the relatively liberal climate of the previous year had already receded, and since steps had already been taken to address his complaints after he had raise many of them directly with Mao. But he still decided to write a criticism of Chinese policy which went beyond the immediate reporting of the famine and of the arrests. \~/

Tibetan Prisoners After the Failed 1959 Uprising

On what happened to Tibetans after the May 10th 1959 Tibetan uprising, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote in his 1962 report to Zhou Enlai: “Most of the people whom it was not necessary to arrest [ke bu ke bu bu de ren] and many good and innocent people were unscrupulously charged with offences, maligned, and categorised with criminals; this has astounded people of integrity.” People “were arrested... put under surveillance, jailed or subjected to labour reform: the number of prisoners in the whole of Tibet reached a percentage of the total population which has never been surpassed throughout history. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“Among those of the upper strata in Tibet who were imprisoned, there were many officials of the official Tibetan local government who had been ranked as chief criminals of the rebellion [panluan zuikui]. On 10th March 1959, the leaders of the rebellion made their reactionary announcement in the Luobulinka [Norbu Linka]. Between that date and 19th March, they convened various types of meetings of the monastic and secular officials of the original Tibetan local government on the subject of the rebellion, in the Luobulinka and other places. Most of those officials who had been ranked as chief criminals of the rebellion were, at the time of the rebellion in Lhasa in 1959, simply participants in those meetings. All those who were captured at the time of suppression of the rebellion were perfunctorily swept together, regarded as chief criminals of the rebellion and imprisoned. |

“However, what if we ask whether or not these people were all leaders and/or chief criminals of the rebellion? It is very difficult to say that this is the case. At the time when the meetings relating to the rebellion were convened, the chief criminals of the rebellion said: "If you come, nothing will happen to you; if you do not, then you and your entire families will be killed." Just like the saying "If insects do not produce oil, then cut their heads off" [chong bu tu you, jiu yao sha tou], due to the unbearable pressure exerted on them, and to serious threats made by means of special power and force, and driven by thoughts of selfpreservation, in order to save themselves and their families from danger, they had no choice but to be ordered about by the enemy. This is the first point. |

“The second point is that the leaders of the rebellion used the pretexts [jiekou] of religion and the national interest, and so good people who had deep faith, love and respect for their religion and nationality, and who did not understand the actual situation, were deceived by the enemy. The third point is that because Tibet has a feudal system, and the officials of the local government received favours from and derived their living from the "Juxigong" ; (the original Tibetan local government) since the time of their ancestors, and furthermore since they themselves were officials of the local government, the situation was more or less that they all thought along the lines of "act as the watchdog at the gate of those who feed you". At the time when the Juxigong’s [Gaden Phodrang] political authority was at the crucial point between life and death, people acted rashly because of their affection for their government.” |

Re-Education and Treatment of Tibetan Prisoners

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: First, as regards assembling for training, when studying the Party’s policies, because one hundred people will have one hundred ideologies, everybody will certainly have their own different understanding and viewpoint. It is very important to give patient help and education to those who have a relatively inappropriate viewpoint and understanding. However, not only were things not done in this way, but acute struggles took place, and some people were subjected to cruel ill-treatment. Consequently, once people heard the cry of "Come to study!", their hearts palpitated with terror. The majority of people of integrity felt discouraged and disheartened, laden with anxieties, and lost confidence in reforming themselves to become new people. Some people’s hatred gave rise to various types of evil thoughts; some just wanted to muddle through life by adapting to changing conditions, and in order to attain their own goals, they learned the technique of keeping a considerable distance between what they said and what was in their hearts. Thus, there emerged a considerable number of people who were good at flattering with deceitful talk and brandishing their willingness to pander to others. This created, during the actual reform process, a situation where on the surface it appeared that achievements had been made, but underneath it was the complete opposite.” [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“As regards those formally imprisoned who are in labour reform; owing to there being an excessive number of prisoners, there were difficulties in managing them. In relation to the ideological reform of these people, presumably the situation could not even have been as good as that in the "assembling for training". Furthermore, apart from part of the upper strata who were imprisoned in the Tibet military region and a small number of administrative personnel detained in ordinary prisons who were treated in accordance with the Party and State law, in the majority of other prisons, the personnel and the managing personnel principally responsible did not care about the life and health of the prisoners. |

“In addition, the guards and cadres threatened prisoners with cruel, ruthless and malicious words and beat them fiercely and unscrupulously. Also, prisoners were deliberately transferred back and forth, from the plateau to the lowlands, from freezing cold to very warm, from north to south, up and down, so that they could not accustom themselves to their new environment. Their clothes and quilts could not keep their bodies warm, their mattresses could not keep out the damp, their tents and buildings could not shelter them from the wind and rain and the food could not fill their stomachs. Their lives were miserable and full of deprivation, they had to get up early for work and come back late from their work; what is more, these people were given the heaviest and the most difficult work, which inevitably led to their strength declining from day to day. |

“They caught many diseases, and in addition they did not have sufficient rest; medical treatment was poor, which caused many prisoners to die from abnormal causes. Old prisoners in their fifties and sixties, who were physically weak and already close to death, were also forced to carry out heavy and difficult physical labour. When I went back and forth on my travels and saw such scenes of suffering, I could not stop myself from feeling grief and thinking with a compassionate heart "Why can’t things be different?", but there was nothing I could do. In brief, in 1959 Chairman Mao gave us a directive: because the population of Tibet is small, we should adopt a policy of not killing people or of killing very few people. For example, it was all right not to kill the rebellious leaders La Lu and Luosangzhaxi . This was not only a wise and great idea which was absolutely correct and which touched people, but also it was completely consistent with the actual situation in Tibet. The real chief criminals had to be jailed and undergo labour reform and be punished mercilessly, to warn others against following their example. |

“As for the remaining people who have committed no crimes or have committed minor crimes, if we could strictly control them, so that essentially there would be no arrests, imprisonments and sentences, we could eliminate the bad and protect the good, and then we would obtain the benefits of using medicine appropriate to the symptoms. However, the reality was the opposite to this. Criminals were being locked up everywhere, but this brought no benefit and only created trouble, and there appeared the dead bodies of many criminals whose crimes did not merit the death sentence. This certainly caused the parents, wives, children, relatives and friends in hundreds and thousands of households to be overwhelmed with grief, and it goes without saying that their eyes were constantly filled with tears. |

“Many people were imprisoned, no matter whether they had or had not committed a crime or whether their crime was large or small; and, in addition, bad management led to many people suffering abnormal deaths. The masses of the Tibetan people not only did not welcome this, but moreover they felt dislike and regret, they felt panic-stricken, suspicious and resentful, and they felt pity for those who had been imprisoned. Therefore, these errors and mistakes created conditions where we were cut off from the masses, and those rebels who had fled abroad and those remnants of the rebels scattered in Tibet had even more doubts and fears about us. Not only did they not come forward to surrender, but also this was the principal factor creating the tendency for die-hard counter-revolutionary thought to become stronger. |

“Democratic Reforms” in Tibet in the 1950s

“Democratic Reforms” were initiated after the unsuccessful uprising by Tibetans on March 10, 1959 in Lhasa. Warren Smith of Radio Free Asia wrote: “Democratic Reforms were imposed in Han Chinese areas in the early 1950s. They involved the confiscation of the property and possessions of the capitalist and exploitative classes, along with land redistribution from landlords to peasants. Democratic Reforms were imposed upon central Tibet only after the failed 1959 Tibetan rebellion against Beijing’s rule. [Source: Warren Smith, Radio Free Asia, September 20, 2005 |~|]

“Democratic Reforms were supposed to pave the way for socialist transformation (collectivization and communization) by transferring political power from the exploitative classes to the people. However, in Tibet, Democratic Reforms had the effect of transferring political power from Tibetans to Chinese. Democratic Reforms in Tibet involved the repression of all rebels and class enemies and the redistribution of land to the Tibetan serfs. Primary targets of the campaign were the Tibetan Government, the aristocracy, and the religious establishment, designated by the Chinese as the “Three Pillars of Feudalism.” |~|

“The property and treasury of the Tibetan Government were confiscated by the Chinese state. The lands and possessions of the wealthy landowners were confiscated and redistributed to the poor serfs. Serfs were given title to the land in elaborate ceremonies, only to have their lands confiscated by the government a few years later during communization. The wealth of individual Tibetans was also confiscated, but reportedly much of this found its way into the hands of Chinese officials. |~|

10th Panchen Lama on “Democratic Reforms”

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: “Concerning categorisation into classes, the Party, based on the actual situation in Tibet, proposed a class distinction between the serf owners’ class, and the serf class which included slaves, forming two large classes. The class line during the period of democratic reform was to depend on the poor and suffering serfs and slaves, and to unite not only with the middle-ranking serfs including the rich serfs, but also with the leftists and centrists within the serf-owning class and with all other strength which could be united, to isolate and attack rebels, counter-revolutionaries and the most reactionary serf owners and their agents who obstinately stick to the wrong course, in order to completely eliminate that dark and most cruel feudal serf-owning class and their system. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“All these policies were correct. But because this work was a great responsibility [ganxi da] and very complicated, it was necessary for cadres to cast aside all prejudices which did not correspond with the established policy. They had to carefully investigate and study each person’s individual background, history, circumstances and standpoint, and using the method of seeking truth from facts rely on the actual situation to assign their class and fully consider the rights and wrongs. They had to take the long term view, deal with things as leniently as possible, and apart from attacking without exception those whom it was necessary to attack, the scope of attacks on the remainder had to be strictly controlled, and they had to win over as many people as possible to our side. |

“Although this was very important, when it was carried out in many or most areas, cadres did the complete opposite, and gave no thought as to whether the movement was carried out with care and whether the quality was good or bad; they single-mindedly sought to be fierce, fearful and acute. They did not look at whether their attacks were correct or not - what was important was the scale and quantity of those attacks. In the midst of this storm, they put the majority of those who had ever held posts as "geng bao" (similar to minor heads of villages), "cuo ben" (similar to township heads), monastery administrators and so on, and categorised them as feudal lords and their agents. But if one were to ask whether these people should have been categorised with the feudal lords and their agents, we can say that they should not all have been categorised in this way.

“As regards the "geng bao" and the "cuo ben", the situation was different in different places; there were some who obtained a feudal living because of their post and so on, and these people can be counted as agents of feudal lords. But there were some who were not like this, who took their turn at a post, and who were persons suited to the post, entreated and pushed forward by the people themselves; they obtained no advantage and would suffer losses, and were the agonised victims of vicious beatings by the bureaucrats. To categorise them with the agents of the feudal lords is to muddle up the divisions between the classes. The situation of monastery administrators was the same. As to whether the work of uniting with the middle-ranking and well-off serfs was carried out well or badly, I have already discussed this above. In addition, I will discuss the two issues of attacking and unity below.” |

“Concerning mobilisation of the masses and the struggle. During democratic reform, under the leadership of the Party, the working people who had suffered bitterly in the past stood up, overturned the feudal system and the ruthless ruling serf-owning class that had been oppressing them, thoroughly liberating themselves and becoming the masters of the land and of society. Therefore, the nature of democratic reform could only be one which gives the masses of the working people a definite revolutionary enthusiasm and class consciousness that gets rid of their feudal illusions characteristics". |

“When mobilising the masses, although cadres gathered together the masses and made a report or speech about democratic reform mobilisation and so on, the masses understood very little of it. This is because: (1) in every place at grassroots level, there were no documents about democratic reform in the Tibetan language, or only part of the documents was there, or the documents were there but they were imperfect; (2) the standard of the oral interpreters was very low; (3) the political and cultural knowledge of the masses was deficient; (4) the cadres were not attentive, not patient and put no effort (or not enough) into the problem of how to get all the masses to understand the questions. The situation in relation to studying was, generally speaking, the same; it was carried out whether by persuasion or by force...For reasons of this kind, the majority of the people found it hard to understand in depth the questions of democratic reform. On the other hand, cadres thought that in mobilising the masses and other democratic reform movements they only had to act rapidly, carry out acute struggle, act vigorously, and then their duty would be done.” |

Abolition of Feudalism by the Chinese Communist and Land Reform in Tibet

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: “Concerning land distribution, all the land and all the means of production owned by the serf owners was confiscated and bought out according to whether they had participated in the rebellion or not, and divided between all the people of the agricultural areas. The serf-owning feudal system in Tibet was abolished and the system of ownership by the peasants was established; therefore, the system of land ownership was fundamentally changed. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“But as to whether people would be completely convinced and feel that this confiscating and buying out was fair, this depended entirely on whether the investigation of and distinction between different levels of participation in the rebellion was correct. When investigation is made into whether or not people were rebels, and whether or not they supported and collaborated with the rebellion, we should acquaint ourselves with the cases conscientiously and thoroughly; in dealing with the cases in accordance with the factual situation. We should be as generous as possible, labelling fewer people as rebels, limiting the scale of attack as much as possible and winning over more people. These things would have been of great benefit for strengthening ourselves and weakening and isolating the enemy. However, as I have just set out above, because the investigation was not thorough, careful or in accordance with the actual situation, this led to many people being given the label "black" and to the range of the attack being too broad, and so many households whose property should not have been confiscated did have their property confiscated. This made the people feel suspicious, anxious and disappointed with us. As regards the buying out, previously our leading patriotic and progressive people had expressed the view and attitude that there was no need to carry this out. This was because the Tibetan land is created by the labour of the people, and should not be owned by the few. |

“Now, when it is returned to ownership by the working people, we really ought not to receive payment in instalments from the nation for the buying out. As regards investigation of the source of the original ownership of the land and determination of its owner, this was a very complicated matter, which was difficult to do with any precision. These conditions had already been reported, but the Party, in order to take care of those people of the middle and upper strata who were patriotic and against imperialism, and to honour those people who did not take part in the rebellion, still adopted the policy of buying out, and the people of the middle and upper strata expressed their great gratitude and support. But because they were only keen on carrying out a policy of the "san guang", they were not cautious enough and their control of the situation was inadequate; this led to many licenses showing proprietary rights over land [tudi suoyouquan de zhizhao] being burned together with reactionary documents. This produced a situation where either there was no way to find out or it was difficult to find out exactly who were the owners, the size of the area of land, and what issues were involved [qianlian] in relation to the land. | “In addition, there were some differences in the methods used by cadres throughout the area which produced some situations where buying out was carried out inappropriately. This led to some complaints among the feudal lords. However, this related to only a small number of the overall population, and was not very important. When assessing each person’s class, a situation occurred in which some serfs were categorised with the agents of the feudal lords which, when added to the fact that the "Five Winds" also blew a little in Tibet, brought about some losses to the land and to the means of production, housing and surplus grain of the middleranking and well-off serfs. At the same time, if the middle and rich serfs were not extremely cautious in their actions and words, then they were immediately attacked, and became the targets of people’s contempt and insults. Because we had not carried out as well as possible the work of uniting with the medium-ranking serfs including the well-off serfs, they felt frightened and anxious. |

A Han teacher who later became a top revolutionary leader in at the time of the Cultural Revolution told Melvyn Goldstein: “The top leaders of China were still concerned that moving forward too fast with socialism in Tibet could be counterproductive, so they decided to eschew starting socialist agriculture (collectives) in 1959 in favor of allowing rural Tibetans to enjoy a period of private farming. Phündra, a senior Tibetan translator at that time, recalled a key 1959 meeting among Zhou Enlai, Mao Zedong, the Panchen Lama, and Ngabö at which this issue came up. [Source: Melvyn Goldstein, Ben Jiao and Tanzen Lhundrup, “ On the Cultural Revolution in Tibet: The Nyemo Incident of 1969,” University of California Press, 2009 ~]

“At this time they were implementing communes in China, and in Tibet some said we should implement them there as well. Mao and Zhou Enlai met then with Ngabö and the Panchen. I was the translator. Zhou Enlai spoke first, saying, “Do not implement communes in a hurry. First divide the land and give it to the peasants. Let them plant the land and get a taste of the profits of farming. In the past they had no land.” Then Mao said, “Do not start communes too quickly. If you give land to those who had no land in the past and let them plant it, they will become very revolutionary in their thinking and production will increase.”

Impact of “Democratic Reforms” on Animal Herders in Tibet

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: “concerning the "Three Anti’s" and the "Two Benefits" in the animal herding areas. In the carrying out of the "Three Anti’s", the situation was for the most part similar to that in the agricultural areas, described above. As regards the "Two Benefits", because there were comparatively large differences in the characteristics of production and economics of animal herding and the characteristics of agriculture, in order to prevent losses through animal deaths, and steadily develop animal herding, the Party proposed, in the work in animal herding areas in Tibet, and under the principles of no class designation, no struggle and no division [fen], to implement policies which would benefit both herd owners and their serfs. On the one hand this was to turn herd serfs into herd workers; they were to be paid a reasonable wage by the herd owners, and the herd workers themselves were to have an ideology of seeking their own liberation and standing up to be the masters of society, and should look after their herds well. On the other hand, care was to be taken of the legitimate interests of herd owners, in order to bring into play their enthusiasm for herd management. These were policies which were even more relaxed and lenient, careful, appropriate and gradual in their progress than those in the agricultural areas; they were completely appropriate for the specific conditions in Tibet’s herding areas, and therefore entirely correct. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“But when the policies were actually implemented, because our cadres for the most part had just carried out a fierce democratic reform struggle in the agricultural areas, at that time they were hot-headed, and once they arrived in the herding areas they started the "Three Anti’s" and the "Two Benefits" campaigns. They launched a fierce and acute struggle against many herd owners and wealthy herding people, which led to many of these herd owners and wealthy herding people only thinking about how to preserve their own lives; they were unable to carry out management and breeding of their animals. When mobilising the herding serfs, the cadres only laid particular stress on educating them to oppose the herd owners and wealthy herding people, and they neglected the necessary education about the "Two Benefits" policy. So, even though the herd serfs were paid their full salaries, they did not follow instructions about putting the animals out to pasture. Moreover, when the herd owners or wealthy herding people made any slight complaint [shushuo] they were struggled against, and so on. Because in this way, the overall picture was not seen, factors were created on the foundation of the "Two Benefits" policy which were disadvantageous to advancing peace among people and the thriving of livestock. |

“However, many problems also arose. Controlled by the heartfelt desire to swiftly wipe out all backward features in Tibet and leap into a happy and glorious socialist society as soon as possible, the first stage of the "cooperatives wind" blew in Tibet. But at that time the working people of Tibet only had an ideology of democratic reform, the level of their socialist ideology was low, and so their demands were not that pressing. As a result they thought that the land which had been allocated to them at the time of democratic reform would soon no longer be theirs, and so they felt unhappy and their interest in production declined; they did not carry out their agricultural production work carefully, and so a situation arose in which they recklessly used up all the property which, early or late, they had gained. |

Resistance to “Democratic Reforms” in Tibet

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: As regards giving special care and encouragement, in order to encourage their urge for improvement, to those who were able to acknowledge their errors and apologise to the masses and who were willing to repent and renew themselves and thoroughly remould themselves, this is very important, but it has not been done perfectly. Take as an example Gongbao Caidan , of whom I was born. Although there were no serious errors in his behaviour, he was for a period part of the feudal serf-owning class, and so there will have been instances where he contravened the will of the people. He understood the importance of acknowledging his errors and apologising before the masses and of reforming himself properly; so, when democratic reform was carried out in Xigaze [Shigatse], he went of his own accord from Lhasa to Shigatse and did these things (i.e., acknowledged his errors and apologised to the masses - Chinese translator’s note). It goes without saying that in Shigatse he was not cared for and commended, but on the contrary cadres of the work teams instigated struggle against him, including public confrontation and fierce beating, by a group of bad people from the middle and upper strata who had disguised themselves as activists, the eloquent, and opportunists. This is not the only such incident in Tibet. Many other friends like him, who believe in the Party, sympathise with the people, support democratic reform and are willing to reform themselves, have been attacked in the democratic reform struggle. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“This has poured cold water on their well-intended and soaring enthusiasm, discouraging and disheartening them. In addition, two great storms have blown up in the places where democratic reform has been carried out. The first storm was that where people wanted to carry out struggle, even though those who were being struggled against had committed no especially serious crimes or errors, they fabricated many serious crimes, exaggerated, followed their own inclinations, reversed right and wrong and so on. Not only did they unscrupulously frame people ever more fiercely and sharply, violently, arrogantly, boastfully and excessively, without a shred of evidence, and even unjustly persecuting many good people, but also, the people who did these things were praised and rewarded, truth and falsity was not investigated, and the necessary control was not exercised. |

“The second storm was that the target of the struggle should be confronted in a careful, clear and conscientious manner with conclusive evidence of his crime, in order to break down his imposing appearance. This certainly was not done. Once the struggle had started, there were some shouts and rebukes, and at the same time there was hair pulling, beating with fists and kicking, pinching people’s flesh, pushing back and forth, and some people even used a large "lun shi" (this is a steel tool shaped like a key which is specifically used for fighting - Chinese translator’s note) and clubs to beat them fiercely. This resulted in bleeding from the seven apertures in the heads of those who were being beaten and in their falling down unconscious and in their limbs being broken; they were seriously injured and there were even some who lost their lives during the struggle. |

“In this situation, needless to say, those people who had committed crimes, that is, people of the middle and upper strata and the middle and well-off serfs, felt extremely fearful and scared. Many innocent people fled to foreign lands, some who were unable to flee ended up in the unfortunate and terrible situation of throwing themselves into rivers or using weapons to kill themselves. This has produced suspicion and loss of hope in people of integrity. What has happened made the enemy feel satisfied and made us [qin] feel discouraged. These were errors and mistakes which were disadvantageous to solidarity and to our work and which were the source of increasing trouble. Each place is different in terms of the degree of seriousness, differences in character, and whether the variety of cases is large or small. I will not give a specific explanation of the "Six Fondnesses" mentioned above, as they can be understood from many of the other problems discussed in this report.” |

Promises of Religious Reform After the Chinese Takeover of Tibet

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: Whether we look at the whole Tibetan region or at any part of it, more than 99 percent of those in each strata of the people (excepting children) have great faith, love and respect for religion. For this reason, everyone is extremely concerned with the future of religion. Because this is a crucial question of great importance, whether it is dealt with well or badly has a direct influence, in which advantages and disadvantages are interrelated, on whether or not we can obtain genuine warm affection from, and be welcomed by, the masses. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

“Because of this...the Party Central Committee would not only continue to give the masses, both monastic and secular, freedom of religious belief, but also would protect law-abiding monasteries and believers, and that we could carry out religious activities including "teaching, debating, writing" [jiang, bian, zhu] as before. This was really exciting. You also pointed out that it was important to carry out reform of the contaminated religion which for a period had seeped into Tibet’s temples and monasteries, and of the feudal serf-owning system and system of oppression and exploitation, including prerogatives [tequan], which was incompatible with social development, in order to purify the monasteries. |

“Moreover, as a proportion of the overall Tibetan population, the number of monks who did not carry out human reproduction and material production was too high; this was very harmful to population growth and development of production in Tibet. Therefore, it was important to reduce the number of monks, and to let some monks return to secular life, go back to their native places, establish families, start careers, and engage in human reproduction and material production. A certain number of good monks should remain in the monasteries, to engage in religious activities.” |

Destruction of Tibet’s Monasteries

The understanding that many people have is that Tibet’s monasteries were looted and damaged during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). That is partly true but much of the destruction took place before that: mostly between 1959 and 1961 when a campaign against most of Tibet's 6,000 monasteries happened. During the mid-1960s, the monastic estates were broken up and secular education introduced. During the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards, which included Tibetan members, attacked cultural sites, including Buddhist sites in Tibet, throughout China. Few monasteries in Tibet escaped unscathed.

Warren Smith of Radio Free Asia wrote: “The destruction of most of Tibet’s monasteries during China’s Cultural Revolution (1966-76) is fairly well-known. Less well-known is the fact that Tibet’s monasteries were, by the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, already empty shells. Not only had all the lamas and monks and nuns departed—for India, or a secular life, or to prisons and labor camps—but the monasteries had been systematically looted of all their valuables. [Source: Warren Smith, Radio Free Asia, September 20, 2005; Warren Smith is a PHD and the author of “Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations”. |~|] “The destruction of Tibet’s monasteries and religious monuments that occurred during the Cultural Revolution came primarily at the hands of Tibetans, even if at the instigation and coercion by the Chinese. But the wholesale pillage that preceded it was planned and executed by the Chinese state. For Tibet, the Cultural Revolution brought the cataclysmic destruction of the monuments of Tibetan civilization and repression of the most essential elements of Tibetan culture. But equally damaging was a previous campaign, less well-known for its destructive effects, perhaps, because of its innocuous name: Democratic Reforms. The Chinese Communists relied upon two primary campaigns to transform Chinese society—Democratic Reforms and Socialist Transformation. The Cultural Revolution was a third, unplanned campaign that arose out of Communist factional politics.” |~|

Phuntsog Wangyal wrote in the Report From Tibet in 1980: “The official Chinese explanation is that all religious objects and monuments were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and by the Tibetan people. From their own enquiries and interviews with hundreds of people all over Tibet, the delegation formed the following picture of what had actually happened. Most monasteries were destroyed between 1959 and 1961. The larger, more famous ones remained until the Cultural Revolution in 1967, when they too were destroyed.

Sources: 1) PDF: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 (A Few Chapters) by Claude Arpi. 2) TIN News Update / 5 October, 1996 / total no of pages: 3 ISSN 1355-3313: Secret Report by the Panchen Lama Criticises China archived by Samsara – A Tibetan Human Rights Archive; 3) Congressional Panel To Probe Chinese Theft of Tibetan Treasures – Warren Smith / Radio Free Asia

Depopulation of Tibet’s Monasteries During the “Democratic Reforms”

Warren Smith of Radio Free Asia wrote: “Another part of the Democratic Reforms campaign was the depopulation of Tibetan monasteries and confiscation of their lands and wealth. Monks and nuns were “freed” of their religious vows and many high lamas were persecuted. Monastic lands were redistributed to the serfs. Once the monasteries were emptied of their monk population, Chinese art experts and metallurgists made a systematic survey of the contents of each monastery. The most precious artworks, precious stones and the most valuable statues of gold and silver were immediately taken away. The less valuable statues and ritual objects were subsequently taken away by PLA trucks. Over a period of several years almost all Tibetan monasteries were emptied of their contents. [Source: Warren Smith, Radio Free Asia, September 20, 2005 |~|]

“Many Tibetans report seeing convoys of PLA trucks headed to China with the contents of Tibetan monasteries. One Tibetan woman imprisoned in Eastern Tibet near the traditional border with China, Ama Adhe, reports seeing convoy after convoy of trucks loaded with Tibetan Buddhist statues headed to China. Adhe reports that, in the beginning, the trucks contained small, precious statues of gold and silver: later, the larger and less valuable statues were cut up and transported to China to be melted down. Ama Adhe’s story has been published in A Strange Liberation: Tibetan Lives in Chinese Hands, by Tibet scholar David Patt. |~|

“The Chinese Communist Party claimed to represent all the people; therefore, it felt justified in confiscating Tibet’s wealth for its own purposes. The Chinese justified the looting of Tibetan monasteries as a part of the redistribution of wealth of the Democratic Reforms campaign. Tibetans were told that they had been exploited by the monasteries and that now the wealth of the monasteries would be redistributed to all the people. By “all the people,” however, the Chinese meant all the Chinese people, not just the Tibetans. |~|

In “Tibetan Nation: a History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-tibetan Relations,” Warren Smith wrote: “The number of “functioning monasteries”, according to a Chinese estimate, had dropped from 2,711 in 1958 to 370 in 1960, while he number of monks had been reduced from an estimated 114,000 to 18,104 (both figures refer only to the TAR).”

Pu Quiong, the Vice Governor of Tibet (Autonomous Region of Tibet, TAR) in the 1950s, reported that before the rebellion of 1959, which led to the flight of the Dalai Lama, there were 2,700 temples and monasteries with 114,000 monks and 1,600 “living Buddhas”. The “democratic reforms” reduced the monasteries to 550 with 6,900 monks until 1966. After the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1978 were only eight monastery with 970 monks left. Since 1978 until May of this year [1987] 230 monasteries have been renovated or rebuilt again. (Stuttgarter Zeitung, 20 July 1987)**

Tsewang Norbu commented: “For a long time it was easy to blame for the crimes in Tibet alone the so-called left-wing elements of the Cultural Revolution, of which the present Chinese leadership distances itself. The West has made this version uncritically their own. With this detailed and blunt statistics the Vice Governor of the (ART) officially confirmed the contention of the Tibetans (in exile) that most of the destruction took place before rather than during the infamous Cultural Revolution. These figures relate only to the so-called ART, which accounts for about half of the actual Tibet.

Panchen Lama on Destruction of Tibet’s Monasteries During 1950s and 60s

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: “The monastic and secular masses, those people felt disappointed and hurt, incompliant and discontented. But because the masses had temporarily and for a short period suffered strict oppression, they were pressurized and had no alternative but to appear slightly indifferent towards religious belief on the surface, but this was a result of great pressure. Because the religion which they deeply believed in and loved had been greatly weakened, and because they were not permitted to believe, religious feelings grew stronger in the thinking of many people, and their belief was deeper than in the past. So suppressing the wishes of the masses and contravening the will of the people became precisely the reasons for our isolation and was that which brought about failure. This contravenes the instructions of the Party, which have frequently been pointed to and taught, that we should cast aside those actions which cause a serious rift between ourselves and the masses. The people who did these things were truly short-sighted and narrow-minded, and they could only become a laughing-stock.” [Source: The Tibet Information Network (TIN) document “Poisoned Arrow. The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama“ (1997). It quotes from the “Petition of 70,000 characters” by the young 10th Panchen Lama that he submitted to Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai in 1962, and for which he became later imprisoned . Mao called the petition “poisoned arrow shot at the Party by reactionary feudal overlords”, from buddhism-controversy-blog.com /*/]

“Before democratic reform there were more than 2,500 large, medium and small monasteries in Tibet. After democratic reform, only 70 or so monasteries were kept in existence by the government. This was a reduction of more than 97 percent. Because there were no people living in most of the monasteries, there was no-one to look after their Great Prayer Halls [da jing tang] and other divine halls and the monks’ housing. There was great damage and destruction, both by man and otherwise, and they were reduced to the condition of having collapsed or being on the point of collapse.” /*/

“In the whole of Tibet in the past there was a total of about 110.000 monks and nuns. Of those, possibly 10.000 fled abroad, leaving about 100,000. After democratic reform was concluded, the number of monks and nuns living in the monasteries was about 7.000 people, which is a reduction of 93 percent.” /*/

“As regards the quality of the monks and nuns living in the monasteries, apart from those in the Zhashenlunbu [Tashilhunpo] monastery, who were slightly better, the quality of the monks and nuns in the rest of the monasteries was very low. For most of those of the monks in each monastery who were religious intellectuals or who were “good monks” who conducted their affairs in accordance with their religion, the situation was as described above; during democratic reform, owing to attacks and so on it was basically difficult for them to live in peace, and because of this they did not live in the monasteries, or very few of them did so. In reality, the monasteries had already lost their function and significance as religious organizations.” // “Those who have religious knowledge will slowly die out, and religious affairs are stagnating, knowledge is not being passed on, there is worry about there being no new people to train, and so we see the elimination of Buddhism, which was flourishing in Tibet and which transmitted teachings and enlightenment. This is something which I and more than 90 percent of Tibetans cannot endure.” //

Fate of Looted Art Work from Tibet’s Monasteries

Warren Smith of Radio Free Asia wrote: “Tibetan wealth was redistributed by being sold on the international art market or melted down, all for the benefit of the Chinese state. Perhaps not coincidentally, the PRC paid off its considerable debt to the Soviet Union in 1962, even though China was suffering the disastrous economic consequences of the Great Leap Forward. Some Tibetans report the rumor that the Soviets accepted Tibetan gold and artworks as payment. [Source: Warren Smith, Radio Free Asia, September 20, 2005 |~|]

“Decades later, the fate of most Tibetan art is unknown. Many of the most valuable statues and scroll paintings were sold on the international art market. Many of the gold and silver statues were probably melted down. Most of the statues and religious objects of brass and copper were melted down. Many thousands of paintings were reportedly burned. |~|

“In 1982, a team of Tibetans led by Rinbur Tulku—a high-level reincarnate lama (tulku) of the Rinbur Monastery of Markham in eastern Tibet—was allowed to try to recover Tibetan artworks still in China. Twenty-six tons of statues and ritual objects were found and returned to Tibet. Some 13,537 statues of brass and copper were recovered, but almost all statues made of gold or silver had disappeared. Although many were recovered, many more statues of brass or copper had been melted. One foundry near Beijing, only one of at least five foundries that had melted Tibetan statues, had melted down 600 tons by the time the process was stopped in 1973. One can see from these figures that the total number of statues taken from Tibetan monasteries was many hundreds of thousands.

Great Famine in Tibet in 1959-61

The report by the 10th Panchen Lama by Zhou Enlai attributes mass starvation in Tibet in the late 1950s and early 1960s among Tibetans at the time to government directives. The primary concern of the Panchen Lama’s 1962 report was to persuade the Beijing leadership to stop Tibetans dying from starvation, especially in Eastern Tibet, where communes had already been established. The 10th Panchen Lama wrote: "Above all you have to guarantee that the people will not die from starvation. In many parts of Tibet people have starved to death.. . . In some places, whole families have perished and the death rate is very high. This is very abnormal, horrible and grave. In the past Tibet lived in a dark barbaric feudalism but there was never such a shortage of food, especially after Buddhism had spread. The masses in the Tibetan areas were living in conditions of such extreme poverty that the old and young mostly starved to death or were so weak that they had no resistance to disease and died.” [Source: The Tibet Information Network (TIN) document “Poisoned Arrow. The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama“ (1997). It quotes from the “Petition of 70,000 characters” by the young 10th Panchen Lama, from subliminal.org \~/]

The 10th Panchen Lama noted that, as a result of the decision to force people to eat in communal kitchens, people were allowed a ration of around 5 oz (180 gms) of grain per day, supplemented by grass, leaves and tree bark. "This terrible ration is not enough to sustain life and people are forced to suffer terrible pangs of hunger," he wrote, adding that people were still being forced to do hard labour, especially released prisoners. "There was never such an event in the history of Tibet. People could not even imagine such horrible starvation in their dreams. In some areas if one person catches a cold, then it spreads to hundreds and large numbers simply die." \~/

The Panchen Lama places blame on official policies, not drought or some other natural phenomena as Mao claimed. "In Tibet from 1959-1961, for two years almost all animal husbandry and farming stopped. The nomads have no grain to eat and the farmers have no meat, butter or salt. It is prohibited to transport any food or material, people are even stopped from going around and their personal tsampa [roast barley] bags are confiscated and many people are struggled against in public," he says. He goes on to describe a meeting he convened in Qinghai where villagers told him deaths could have been avoided and good harvests achieved "if the state allowed us to eat our fill".

According to The Tibet Information Network: The famine which the Panchen Lama documented in his report had spread throughout China as a result of the Great Leap Forward in 1958, when Mao Zedong ordered the peasants to set up communes as part of a radical acceleration of the advance towards utopian communism. By the time of the Lushan Plenum, a party meeting in August 1959, pragmatic leaders led by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping had already begun to curb the excesses of Mao's programme, but starvations was widespread in China for two more years. The 70,000 Character Petition showed that starvation still existed in Qinghai in 1962, and other evidence shows that in Kham, the adjoining Tibetan area within Sichuan, it continued until 1965. \~/

A report by the Economic System Research Institute in Beijing in the early 1980s found that 900,000 people died during the famine in the Panchen Lama's home province of Qinghai - 45 percent of the population - and 9 million in Sichuan, according to research by the journalist Jasper Becker, author of a major study of the famine issued earlier this year. "No other group in China suffered more bitterly from the famine than the Tibetans," says Becker, adding that famine remained endemic in central Tibet for the next 20 years. \~/

Although the Great Leap was officially acknowledged in the Party's landmark 1981 "Resolution on Party History" as a "serious mistake", it made no mention of famine, referring only to "serious losses to our country and people". Official Chinese texts which are publicly available still avoid the subject and refer obliquely to "the three difficult years" without giving further details.

See Great Leap Forward factsanddetails.com and Great Famine factsanddetails.com

10th Panchen Lama on the Great Famine in Tibet in 1959-61

In the report to Zhou Enlai in 1962, the 10th Panchen Lama wrote: “As regards the livelihood of the masses, after suppression of the rebellion and democratic reform, life gradually became more stable and changed for the better....But owing to some errors and mistakes in work and to the work style of some cadres, difficulties were produced in the lives of the masses in some areas. Owing to the "Five Winds" [wu feng] appearing in some agricultural areas, to the work of grain collection being done too strictly, to the low level of grain which the masses were permitted to retain, so that there was barely enough grain for consumption, and also to the fact that some of the masses used grain in an inappropriate way, many families ran out of grain. [Source: The Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama: Report on the sufferings of the masses in Tibet and other Tibetan regions and suggestions for future work to the central authorities through the respected Premier Zhou Enlai 1962 |]

As regards people complaining, some people complained because they really had run out of grain, and some people complained because they had a little bit of grain left and did not want to let others know about it; there were all kinds of situations. It was very important, on the foundation of enhancing the class consciousness of the masses, to thoroughly and conscientiously carry out overall investigation and review, to provide relief for those households which have run out of grain, not to allow the masses to go hungry, and for those households which have grain not to have to hand it over as collective grain without reason. But some cadres failed to do this, and they assumed that the circumstances in some individual households were representative of those in all households, with the result that some households took advantage of the government, and some households which had genuinely run out of grain were unable to gain relief. Because at that time there was a shortage of grain, people who lacked grain could not obtain it from elsewhere. Consequently, in some places in Tibet, a situation arose where people starved to death. This really should not have happened, it was an awful business [zhuolie] and very serious. |

“In the past, although Tibet was a society ruled by dark and savage feudalism, there had never been such a shortage of grain . In particular, because Buddhism was widespread, all people, whether noble or humble, had the good habit of giving help to the poor, and so people could live solely by begging for food. A situation could not have arisen where people starved to death, and we have never heard of a situation where people starved to death. In Tibet during the two years of 1959 and 1960, free exchange of agricultural and animal herding products more or less ceased. Because of this, those people who worked in animal herding were extremely short of grain, and the peasants were short of meat, butter, salt and soda, which resulted in difficulties in life in the agricultural and the animal herding areas. In order to solve these problems in their lives, people had to eat many of their animals, which created conditions disadvantageous to the development of production. At the time of democratic reform, it was forbidden to travel back and forth to transport materials and grain, and people’s travel to different places was very restricted. Consequently the supply of goods which the towns needed and which had to be brought in from the countryside was almost cut off. A lot of surplus grain was also collected from the people in the towns; perhaps collection was excessive, and even grain and tsampa contained in sachets was collected. |

“Families who secretly concealed a few litres [sheng] of grain and tsampa were struggled against, which appears very petty and mean-spirited. Most households were ransacked, and almost all of the residents’ own stores of grain, meat and butter were taken away. Because the government supplies of grain, oil and butter to the cities were not supplied universally and in time, or were not supplied properly, many of the residents were very short of grain; some ran out of grain, and were very short of meat, butter, oil and so on; there was not even any lamp oil. Even firewood could not be bought. People were frightened and anxious and complained incessantly, and they were not content in their work. This made the situation in the city very tense, harm was done both to reputation and in reality [ming shi liang sun]. In addition, domestic spinning throughout the area stopped for a period, which had an effect on clothing for the masses. |

“At the time of democratic reform, it was forbidden to travel back and forth to transport materials and grain, and people’s travel to different places was very restricted. Consequently the supply of goods which the towns needed and which had to be brought in from the countryside was almost cut off. A lot of surplus grain was also collected from the people in the towns; perhaps collection was excessive, and even grain and tsampa contained in sachets was collected. Families who secretly concealed a few litres [sheng] of grain and tsampa were struggled against, which appears very petty and mean-spirited. Most households were ransacked, and almost all of the residents’ own stores of grain, meat and butter were taken away. Because the government supplies of grain, oil and butter to the cities were not supplied universally and in time, or were not supplied properly, many of the residents were very short of grain; some ran out of grain, and were very short of meat, butter, oil and so on; there was not even any lamp oil. Even firewood could not be bought. People were frightened and anxious and complained incessantly, and they were not content in their work. This made the situation in the city very tense, harm was done both to reputation and in reality [ming shi liang sun]. In addition, domestic spinning throughout the area stopped for a period, which had an effect on clothing for the masses. |

Victim of the Great Famine in Tibet

The final chapter “My Tibetan Childhood: When Ice Shattered Stone” by Naktsang Nulo described the Great Leap Forward and Great Famine period of 1959 in Tibet. The state orphanage where Naktsang Nulo (Nukho) and his brother are staying at is decimated by famine. According to the Los Angeles Review of Books: The two brothers, by now hardened plateau survivalists, hunt and slaughter thousands of marmots and sheep for food.”

In a review of “My Tibetan Childhood,” Kevin Carrico wrote: “The boys are released after eighteen days in the hole to attend a nearby school. Known as the “Joyful Home,” the two young inhabitants are at first impressed with the abundance of food and are truly joyful, despite other students’ “revolutionary” criticisms of their religious “superstition.” [Source: Kevin Carrico, University of Oklahoma, MCLC Resource Center Publication, December, 2015]

“As 1959 arrives, food shortages first foreshadowed in the underground prison gradually extend outward to this Joyful Home. The remainder of the book provides a harrowing portrayal of life in Tibet during the Great Leap Forward famine: children eating leather, consuming rodents, and using their last ounces of energy to drag their deceased companions out of their tents.

Two images from this section of the book are particularly evocative: the first is dead children with their pillows covered in oily vomit, deceased after gorging themselves on stolen dog fat, while the second is living children, standing by a river, chewing raw human flesh off of a leg, distracted only by the promise of the narrator’s pika meat. When the narrator and his brother leave Joyful Home to return home with their adult companions, only 63 out of over 1,600 Joyful Home residents had survived the famine.” After this Nulo goes off to a Communist-run school. He grows up to be a policeman, then a prison governor.

According to the Los Angeles Review of Books: “Naktsang Nulo published this account in Tibetan, inside Tibet, in 2007, where it quickly became a bestseller, then was banned. His child’s-eye narrator has a clarity of vision in the midst of suffering that becomes a kind of Buddhist liberation, but at the same time a ferociously political j’accuse. As scholar Robert Barnett points out in the introduction, it’s a long-form account of the Communist invasion of Tibet that never once uses the word “communism.” And yet complicity in cyclic violence is at the heart of this story.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022