CHINESE INVASION OF TIBET IN 1950

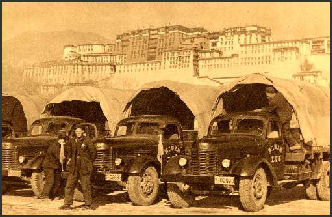

ChineseTrucks under Potala Palace The People's Republic of China, established in 1949, inherited its predecessor's territorial claims. China invaded Tibet in 1950. Tibetan resistance collapsed quickly, and the government of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama (b. 1935) signed an agreement recognizing Chinese sovereignty over Tibet.

The 1950 invasion was justified by the Chinese as necessary in order to destroy inequitable feudalism in Tibet and to bring progress, education, and social justice. Friction between the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama and the succession of the 10th Panchen Lama, with rival candidates supported by Tibet and China, was another excuse for the Chinese invasion of Tibet.

Tibet may have been poor and isolated when the People’s Liberation Army began its invasion in 1950, but it was also a land whose people considered themselves essentially independent.At the time Communist forces marched into Tibet, the former empire was ill- prepared to defend itself. It had a poorly trained army, no paved roads, and no more than a few speakers of any Western language. Had the country modernized earlier instead of shunning reforms, the Dalai Lama later wrote, "I am quite certain that Tibet's situation today would be very different." [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker]

At the time the Chinese entered Tibet, the attention of the world was focused on the Korean peninsula, where the North Koreans had just invaded South Korea. Tibet was perceived in the West as mythical kingdom like Shangri-la and little was known about it. Tibet and its appeals to the U.N. for help after the invasion were largely ignored. Vetoes by the Soviet Union blocked any United Nations intervention. Not helping matters wee the facts that Tibet never joined the League of Nations or the United Nations. "It never occurred to us that our independence...needed any legal proof to the outside world," the Dalai Lama wrote in his autobiography.

See Separate Articles:TIBET IN THE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN REVOLT IN 1959 AND THE CHINESE TAKEOVER OF TIBET factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE REPRESSION IN TIBET IN THE LATE 1950s AND EARLY 1960s factsanddetails.com ; SECRET CIA WAR IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ; STORY OF A MILITANT TIBETAN MONK factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources on Tibet: Central Tibetan Administration (Tibetan government in Exile) www.tibet.com ; Chinese Government Tibet website eng.tibet.cn/; Wikipedia article on Tibet Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Tibetan History Wikipedia ; Tibetan News site phayul.com ; Snow Lion Publications (books on Tibet) snowlionpub.com ; Tibet Activist Groups: Free Tibet freetibet.org ; Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy tchrd.org ; Students for a Free Tibet studentsforafreetibet.org ; Students for a Free Tibet UK /sftuk.org ; Friends of Tibet friendsoftibet.org ; Campaign for Tibet (Save Tibet) savetibet.org ; Tibet Society tibetsociety.com ; Tibetan Studies and Tibet Research: Tibetan Resources on The Web (Columbia University C.V. Starr East Asian Library ) columbia.edu ; Tibetan and Himalayan Libray thlib.org Digital Himalaya ; digitalhimalaya.com; Center for Research of Tibet case.edu ; Tibetan Studies resources blog tibetan-studies-resources.blogspot.com

Book: “Tibetan Civilization” by Rolf Alfred Stein. Robert Thurman, a friend of the Dalai Lama and professor of Indo-Tibetan studies at Columbia University, is regarded the preeminent scholar on Tibet in the United States. “The Dragon in the Land of Snows” by Tsering Shakya (Random House, 1998) is a first rate book on the history of Tibet under Chinese occupation. “History of Modern Tibet” by Melvyn Goldstein is a two-volume set that documents the events during the first half of the twentieth century that culminated in the arrival of the PLA in Lhasa in 1951 and the incorporation of Tibet into the People’s Republic of China. The second volume of that history leaves off in 1955, just as Mao launches the Socialist Transformation Campaign throughout China and before the Khamba uprising in Sichuan Province against the implementation of socialist reforms spills over into Tibet.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947" by Tsering Shakya Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, volume 2: The Calm before the Storm: 1951-1955" by Melvyn C. Goldstein Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 3: The Storm Clouds Descend, 1955–1957" by Melvyn C. Goldstein Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 4: In the Eye of the Storm, 1957-1959" by Melvyn C. Goldstein | Amazon.com; “When the Iron Bird Flies: China's Secret War in Tibet” by Jianglin Li and Dalai Lama Amazon.com; “Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959" by Jianglin Li and Susan Wilf Amazon.com; “Flight of the Bön Monks: War, Persecution, and the Salvation of Tibet's Oldest Religion” by Harvey Rice , Jackie Cole , et al. Amazon.com; “The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering” by Melvyn C. Goldstein , William R Siebenschuh, et al. Amazon.com; “A Poisoned Arrow: the Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama” By Bskal-Bzan-Tshe-Brtan Amazon.com; General History: “Tibet: A History” by Sam van Schaik Amazon.com; “A Historical Atlas of Tibet” by Karl E. Ryavec Amazon.com; “Histories of Tibet” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer , William A. McGrath, Amazon.com; “Himalaya: A Human History” by Ed Douglas, James Cameron Stewart, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet & Its History” by Hugh Richardson (1989) Amazon.com; "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein Amazon.com; “The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama” by Thomas Laird Amazon.com

Events Before the Chinese Arrival in 1950

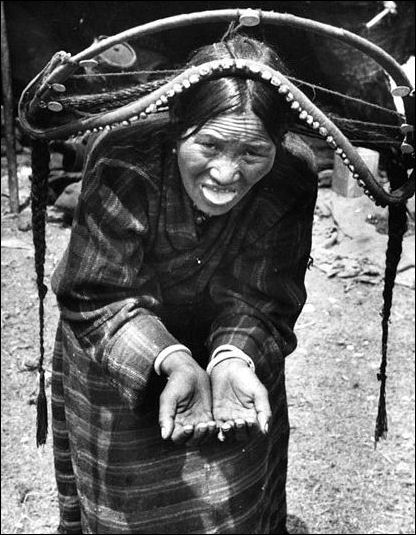

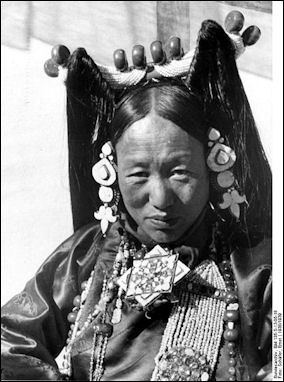

Tibet in 1938 before

the Chinese took it over

Independent Tibet was no Shangri-La. It very isolated and poor. Before the Chinese arrived, life expectancy was 36 years, the literacy rate was five percent and 95 percent of the population were hereditary serfs and slaves. Corruption and crime were endemic. Bandits roamed the countryside; lamas and noblemen enriched themselves on the backs of poor peasants. Potala palace was described as "a real robbery shop...an eggshell intact on the outside but rotten within." Some argue the system was not as harsh as the Chinese have made it out to be. Robert Barnett, director of modern Tibetan studies at Columbia University told the Times of London, “The Chinese trick is to say the words “serf”and “feudal”and make us think brutal.”

In the 1930s a feud broke out between the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama. In 1933, the 13th Dalai Lama died and the country fell under the leadership of the regent of Reting. In 1947, an attempted coup, known as the Reting Conspiracy, shook Lhasa. In 1949, the Communists took over China. Many Chinese felt that had a moral obligation to liberate Tibetans from a bad system and help Tibet modernize.

Immediately after the communist party took power in China in 1949 it began asserting its claim that Tibet was part of Chinese territory and its people were crying out for "liberation" from "imperialist forces" and from the "reactionary feudal regime in Lhasa". In 1950, the 15-year-old Dalai Lama, his entourage and select government officials, evacuated the capital and set up a provisional administration near the Indian border at Yatung. In July 1951 they were persuaded by Chinese Officials to return to Lhasa. ~

Many Tibetans, especially educated ones in the larger towns, welcomed the Chinese and were eager to modernize Tibet. They embraced the Communists as means of advancing a feudal society ruled by elite monks and landlords.

Chinese Take on Tibetan History

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker: “Both sides agreed that China's Mongol rulers had amassed great authority in Tibet by the thirteenth century. But Tibetans say the bond was based principally on a shared religion, and they argue that the Mongols did not represent the Chinese. Historians in China consider the Mongol era the beginning of seven hundred years of political sovereignty over Tibet.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, October 4, 2010]

Historically, Osnos wrote “the vast majority of Han are proud of their role in Tibet, which they see as a long, costly process of extending civilization to a backward region. The Han in the lowlands had little in common with the pastoral people in the mountains — no shared language or diet — and Chinese historians explained that a Tang-dynasty princess taught Tibetans about agriculture, silk, paper, modern medicine, and industry, and stopped them from painting their faces red.”

“In the twentieth century, when China secured Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and Xinjiang within its borders, the move was hailed by the Chinese people as the end of a century of foreign invasion and humiliation. The Dalai Lama, from that perspective, stood in the path of history, and when he went into exile Chinese newsreels recorded images of farmers denouncing their former landlords and destroying records of hereditary debts.”

“Anyone over fifty years old in China today has grown up with those scenes dramatized in influential films like ‘serf,” a 1963 drama about a freed Tibetan servant and his grateful encounter with the People’s Liberation Army. Han Chinese who are only a generation or two removed from poverty are inclined to view China’s investment as a sacrifice.” A Chinese graduate student at Yale told the The New Yorker, “My father is an educated man. He has worked all over Tibet for years and, to this day, he can’t really respect Tibetans. He doesn’t see any intellectual output from them.”

Advance by the Chinese into Tibet

On October 7, 1950, some 40,000 battled-hardened Chinese P.L.A. troops crossed the upper Yangzte River into eastern Tibet. A poorly-armed force of 4,000 Tibetans was quickly overrun. A Tibetan who recalled hearing about the advance on the radio, later told the Independent, "The announcement was not a complete shock: we had heard reports that the poor people of China had risen up in revolution, and all the rumors that these Communists would come to Tibet. But still there was panic."

Within a few weeks, the People's Liberation Army had penetrated Tibet as far as Chamdo the capital of Kham province and headquarters of the Tibetan Army's Eastern Command. Buddhist monks prayed hard but there efforts didn't help. The Chinese easily took Chamdo and captured more than half of Tibet's 10,000-man army. Governor, Ngawang Jigme Ngabo, taken prisoner.

In response to crisis, the Tibetan government enthroned the 15-year-old, 14th Dalai Lama. There was jubilation and dancing in streets but all this, and appeals by the United Nations, had little effect on the Chinese advance. Meanwhile, Chinese forces were stealthily infiltrating Tibet's north-eastern border Province, Amdo, but avoiding military clashes which would alert international interest.

On September 9, 1951, a vanguard of 3,000 Chinese "liberation forces", carrying portraits of Mao Zedong, peacefully entered Lhasa. China claims it "peacefully liberated" Tibet in 1950, saying it ended serfdom and brought development to a backward, poverty-stricken region. China’s leadership said it had to come to “liberate” Tibet from “Imperialism” even there was no Americans and only about a handful of Britains in Tibet at the time. [Source: buddhism-controversy-blog.com, April 21, 2013]

Aftermath of the Chinese Invasion

Beijing enacted the 17-point Agreement on Measures for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet with a forged seal of the Dalai Lama in March, 1951. In this document Beijing vowed not to change the Tibetan social system and promised a Hong Kong-like two-system structure, self government and freedom of religion but provided no mechanisms for guaranteeing the agreement’s terms. The agreement stipulated that Tibet would be self-governing under the Dalai Lama.

According the Tibetan-Chinese agreement of May, 1951 Tibet became a "national autonomous region" of China under the traditional rule of the Dalai Lama, but under the actual control of a Chinese Communist commission. The Communist government introduced far-reaching land reforms and sharply curtailed the power of the monastic orders. In 1951, when Gen. Zhang Jinwu was sent to Lhasa as the first representative of Communist China in Tibet, he reportedly asked Mao Zedong if he should kotow to the Dalai Lama as representatives of the Chinese Emperor had done in the past. Mao is said to have replied: “For the sake of the whole Tibetan people, why not?”[Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Columbia University Press]

Later, Beijing reneged on most of the promises it made. Nevertheless, the Chinese government undermined the old order by cultivating the Panchen Lama, the second-ranking leader of Tibetan Buddhism, and recruiting Tibetan collaborators.

Dalai Lama and the Invasion of Tibet

Tibet in 1938

The Dalai Lama was 16 when the Chinese entered Lhasa in 1950. He responded to the crisis by taking over his duties as the temporal leader of Tibet, two years before he was officially supposed to do so. "I had to put my boyhood behind me," he said, "and immediately prepare myself to lead my country, as well as I could, against the vast power of Communist China."

The Dalai Lama wrote in Time, "I was very young when I first heard the word communist...Some monks who were helping me with my studies...had talked about the destruction that had taken place since the Communists came to Mongolia. We did not known anything about Marxist ideology. But we all feared destruction and thought of Communists with terror."

As a young man the Dalai Lama was deeply interested in Marxism. He was impressed by Chinese reforms and wrote poems praising Mao Zedong. "It was only when I went to China in 1954-55 that I actually studied Marxist ideology and learned about the Chinese Revolution. Once I understood Marxism, my attitude changed completely. I was so attached to Marxism, I even expressed my wish to become a Communist party member."

"Tibet at that time was very, very backward," teh Dalai Lama said. "The ruling class did not seem to care, and there was much inequality. Marxism talked about an equal and just distribution of wealth. I was very much in favor of this.” His view changed when “the Chinese Communists brought to Tibet a so-called liberation.” “Chinese Communists carried out aggression and suppression in Tibet. Whenever there was opposition, it was simply crushed. They started destroying monasteries and killing and arresting lamas."

"In the beginning, I had hoped that we could find a peaceful solution. I even went to China to meet Chairman Mao. We had several meetings in 1955...Until the summer of 1956, the Chinese had some level of trust in me." That changed after the Dalai Lama made a visit to India with Beijing approval and visited Tibetan freedom fighters there.

Events After the Chinese Occupation of Tibet in 1951

A 1951 treaty spelling out how power would be shared between Beijing and Lhasa swiftly unraveled amid violations and recriminations. By 1954, 222,000 members of the People's Liberation Army (PLA) were stationed in Tibet and famine conditions became rampant as the country's delicate subsistence agricultural system was stretched beyond its capacity. [Source: Tibet Oline tibet.org ~]

“Li Jianglin is the daughter of CCP officials. She moved to New York in the 1980s and became a librarian and got to know some Tibetan people in Queens. In her book: “Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959", she wrote in Mao had active plans from very early on to impose his policies throughout Tibet despite the promises of the ‘Seventeen-Point Agreement’ [that guaranteed Tibetan self-rule within the PRC], even though he was aware that this would entail bloodshed. His explicitly stated view was that he welcomed Tibetan unrest and rebellion — and even hoped it would increase in scale — as it would provide him with an opportunity to ‘pacify’ the region with his armies.”[Source: China Channel, LARB, November 20, 2020]

In April 1956, the Chinese inaugurated the Preparatory Committee for the Autonomous Region of Tibet (PCART) in Lhasa, headed by the Dalai Lama and ostensibly convened to modernize the country. In effect, it was a rubber stamp committee set up to validate Chinese claims. In the late fifties, Lhasa became increasingly politicized and a non-violent resistance evolved, organized by Mimang Tsongdu, a popular and spontaneous citizens' group. Posters denouncing the occupation went up. Stones and dried yak dung were hurled at Chinese street parades. During that period, when the directive from Beijing was still to woo Tibetans rather than oppress them, only the more extreme Mimang Tsongdu leaders and orators faced arrest.

Revolts and Atrocities in Kham and Amdo Pressure Lhasa

In February 1956, revolt broke out in several areas in Eastern Tibet and heavy casualties were inflicted on the Chinese occupation army by local Kham and Amdo guerilla forces. Chinese troops were relocated from Western to Eastern Tibet to strengthen their forces to 100,000 and "clear up the rebels." Attempts to disarm the Khampas provoked such violent resistance that the Chinese decided to take more militant measures. The PLA then began bombing and pillaging monasteries in Eastern Tibet, arresting nobles, senior monks and guerrilla leaders and publicly torturing and executing them to discourage the large-scale and punitive resistance they were facing. ~

In research on eastern and northern Tibet (Kham and Amdo), for her book: “Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959", Li Jianglin calculated, based on published PRC statistics, that between 1957 and 1963, the population of Qinghai province alone dropped by over 20 percent, or 120,000 people — not counting internal dislocation, imprisonment, immiseration. Even official PRC reports admit that in some areas, over 70 percent of rural Communist Party members defected and fought on the rebel side. Starving Khampa and Amdo survivors pour into Lhasa and helped trigger the revolt there in 1959. [Source: China Channel, LARB, November 20, 2020]

Li told the New York Times: ““In 2012, I drove across Qinghai to a remote place an elderly Tibetan refugee in India had told me about: a ravine where a flood one year brought down a torrent of skeletons, clogging the Yellow River. From his description, I identified the location as Drongthil Gully, in the mountains of Tsolho Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. I had read in Chinese sources about major campaigns against Tibetans in that area in 1958 and 1959. About 10,000 Tibetans — entire families with their livestock — had fled to the hills there to escape the Chinese. At Drongthil Gully, the Chinese deployed six ground regiments, including infantry, cavalry and artillery, and something the Tibetans had never heard of: aircraft with 100-kilogram bombs. The few Tibetans who were armed — the head of a nomad household normally carried a gun to protect his herds — shot back, but they were no match for the Chinese, who recorded that more than 8,000 “rebel bandits” were “annihilated” — killed, wounded or captured — in these campaigns. [Source: Luo Siling, Sinosphere, New York Times, August 14, 2016]

“I wondered about the skeletons until I saw the place for myself, and then it seemed entirely plausible. The river at the bottom of the ravine there flows into a relatively narrow section of the Yellow River. In desolate areas like this, Chinese troops were known to withdraw after a victory, leaving the ground littered with corpses.

Reforms Under Liberal Chinese Rule in the 1950s

Throughout most of the 1950s, most Tibetans still had control over their own affairs and the Dalai Lama continued to live in Lhasa. The Chinese presence was generally benign and positive. They built roads, schools and hospitals and let the Tibetans practice their religion and customs. Tibetans admired the Chinese for their honesty and efficiency but were taken aback by many Chinese customs and habits. They were appalled by the way Chinese put worms on hooks and fished and used "night soil" (human feces) as fertilizer for vegetables. Recalling how life improved under the Communists, one old Tibetan man told the Times of London, he was able to try rich yak butter tea for the first time. “It was not great, but it was better [than what he had before]. We could eat rice and noodles and salty butter tea, which we did not have before.”

According to the Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism: The Chinese organized serfs in Tibet, carried out antireligious propaganda, and recruited and trained Tibetan cadres. Nonetheless, the Chinese government worked officially through the Dalai Lama's government. In most of Tibet, life continued on with little interference by the Chinese authorities through the 1950s. [Source: Encyclopedia of Western Colonialism since 1450, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Mao and the Dalai Lama in 1954

A new kind of feudal system was created, with taxes given to Chinese government instead of the lamas. The Chinese presence caused food shortages and an increased cost of living. Demonstrations and disturbances occurred from time to time. Reports of massacres and political indoctrination came out of Kham.

But some had predicted bad things were ging to happen In 1932, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama wrote in his will that Tibet as Tibetans had known it was about to be destroyed by “barbaric red Communists.” “Our spiritual and cultural traditions will be completely eradicated. Even the names of the Dalai and Panchen Lamas will be erased...The monasteries will be looted and destroyed, and the monks and nuns will be killed or chased away...We will become like slaves to our conquerors...and the days and nights will pass slowly with great suffering and terror.”

Chinese Take Over Tibet

The Chinese slowly undermined Tibetan authority. The Tibetan areas of Kham and Amdo were annexed and added to the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Qinghai. Monasteries were looted and land was confiscated from the Tibetan aristocracy. A propaganda campaign was launched. One Tibetan told the Independent, "A loudspeaker was set up in the heart of Lhasa, broadcasting propaganda in Tibetan. I kept asking myself what all these new ideas were, these -isms; socialism, communism, capitalism and imperialism. We had never heard of them before."

Many educated Tibetans actually welcomed the Chinese communists in 1950. The Buddhist clergy was seen, not without reason, as hidebound and oppressive. Chinese communism promised modernization. In the years following 1950, when the Chinese asserted sovereignty over Tibet but accorded it a certain amount of autonomy, Tibetans found the soldiers of the People's Liberation Army to be polite and friendly. Gonchoe, a 74-year-old veteran of the Tibetan resistance movement told Belgian author Birgit van de Wijer: "The first time the Chinese people came into my country, they were helping people and brought whatever we needed." [Source: Dinah Gardner, South China Morning Post, January 30 2011]

Deng Xiaoping and the Dalai Lama in 1954

Things began deteriorate after Mao remarked during a 1954 meeting with the Dalai Lama that "religion is poison" and Beijing voiced its determination in freeing Tibetan serfs by breaking the lock on power by the Tibetan monasteries and aristocracy. After that the pace of monastery destruction increased, hundreds of thousands of monks and nuns were driven from the monasteries. The Communists deliberately killed many senior monks regarded as the most powerful people in Tibet. The process continued through the Cultural Revolution. Many Tibetans, possibly more than a million, starved to death during Chairman Mao's Great Leap Forward campaign.

In exile, the Dalai Lama looked for allies, but no nations recognized Tibet’s claim to independence. Some of the Dalai Lama’s brothers pursued another strategy: the C.I.A. was eager to cause problems for the new Chinese government, However, by the mid-50s, China had begun to force its agrarian reforms onto people in the east of the country. "They killed high lamas and were against religion, and they caught people who didn't want to be communists," Gonchoe says.

How China Tried to Control Tibet

Benno Weiner wrote “The Chinese Revolution on the Tibetan Frontier”. According to the Los Angeles Review of Books: Weiner’s interest is in the details of state- and nation-building in nomadic Tibet, and particularly in the ideology of the United Front — the organization tasked with persuading influential members of society to ally with the Communist cause. (Today, among other things, the United Front manages religious figures within China, runs the Confucius Institutes abroad, and conducts influence-campaigns among Chinese diaspora communities world-wide.) In Weiner’s telling, before the Communists arrived, the fragmented chiefdoms of the Tibetan plateau had operated under an imperial “hub-and-spoke” political logic, in which non-Chinese elites rendered nominal allegiance to successive Chinese states, in exchange for official recognition and local autonomy. [Source: China Channel, LARB, November 19, 2020]

“This arrangement persisted into the early Maoist period, when the United Front, backed by PLA artillery, proffered peaceful surrender terms to those Tibetan leaders who would cooperate. United Front ideology was “voluntaristic,” in that it expected these traditional units to willingly undertake Communist reform. Over the course of the 1950s, this “sub-imperial” alliance was transformed into a “high-modernist” direct-relation between individuals and the socialist state. To put this in layman’s language, Weiner’s book is a chronicle of the brutal betrayal of these initial surrender agreements: see-sawing campaigns of communization, de-communization and re-communization; compulsory re-education, destruction of monasteries, mass-imprisonment, starvation, and Tibetan “banditry.” Finally, in 1959 the whole plateau erupted in rebellion, and was crushed by the PLA.

“Weiner notes that the present PRC narrative of “peaceful liberation” is predicated on defining away most of what happened in the 1950s: “A decade-spanning picture emerges in which Qinghai’s grasslands were racked by sustained (if diffused) resistance and an ever-present potential for violent conflict.” Weiner carefully demurs about the death toll of all this: “Extant sources simply do not allow for such undertakings at this time.” Nevertheless, “much of Amdo appears to have been enveloped in a cloud of political terror and state violence that could strike irrespective of class status or prior collusion.” Amid the brutality, there are some fascinating details: Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, appears briefly as the “primary architect of the 1950s United Front in Northwest China,” at least according to recent propaganda. At another point, the assembled Tibetan nomads get a lecture on the evils of capitalist countries, especially the scourge of racism in America (spot on!).

Book: “The Chinese Revolution on the Tibetan Frontier” by Benno Weiner (Cornell University Press June 2020).

Chinese View of the Chinese Occupation of the 1950s

According to to Chinese government: “With the founding of the People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949, the Tibetan areas in the western part of the country was liberated one after another and the Tibetans there entered a new period of historical development. In 1951, representatives of the Central People's Government and the Tibet local government held negotiations in Beijing and signed on May 23 a 17-article agreement on the peaceful liberation of Tibet. Soon afterwards, the central government representative Zhang Jingwu arrived in Lhasa and Chinese People's Liberation Army units marched into Tibet from Xinjiang, Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan in accordance with the agreement.[Source: China.org china.org |]

“China's First National People's Congress was held in Beijing in 1954. The Dalai Lama, Bainqen Erdini and representatives of the Tibetan people attended the congress and later visited various places in the country. The State Council then called a meeting at which representatives of the Tibet local government, the Bainqen Kampo Lija and the Qamdo People's Liberation Committee formed a preparatory group for the establishment of the Tibet Autonomous Region after repeated consultations and discussions. In April 1956, a preparatory committee for the purpose was officially set up. |

“Regional autonomy and social reforms were introduced cautiously and steadily in one Tibetan area after another according to their specific circumstances arising from the lopsided development in these areas due to historical reasons. A number of autonomous administrations have been established in Tibetan areas since the 1950s. They include the Tibet Autonomous Region, the Yushu, Hainan, Huangnan, Haibei and Golog Tibetan autonomous prefectures and the Haixi Mongolian, Tibetan and Kazak Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai Province; the Gannan Tibet Autonomous Prefecture and the Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County in Gansu Province; the Garze and Aba Tibetan autonomous prefectures and the Muli Tibetan Autonomous County in Sichuan Province; and the Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan Province. |

“In light of the historical and social development of the Tibetan people, the central government introduced democratic reforms in various places according to local conditions and through patient explanation and persuasion. Experiments were first carried out to gain experience. A campaign against local despots and for the reduction of rent and interest was unfolded in the Tibetan areas of Northwest China in 1951 and 1952. In farming areas, people were mobilized to abolish rent in labor service and extra-economic coercion in the struggle to eliminate bandits and enemy agents. Sublet of land was banned. But rent for land owned by the monasteries was either intact or reduced or remitted after consultation. In pastoral areas, aid was given to herdsmen to develop production and experience was accumulated for democratic reforms and socialist transformation there. |

“In the Tibetan areas of Southwest China, peaceful reforms were introduced between 1955 and 1957 in the farming areas. Feudal land ownership and all feudal privileges were abolished after consultation between the laboring people and members of the upper strata. Usury was also abolished and slaves were freed and given jobs. The arms and weapons of manorial lords were confiscated. The government bought out the surplus houses, farm implements, livestock and grain of the landlords and serf owners. |

“It was clearly laid down in the agreement on the peaceful liberation of Tibet that democratic reforms would be carried out to satisfy the common desire of the peasants, herdsmen and slaves. But, in light of the special circumstances in Tibet, the central government declared that democratic reforms would not be introduced before 1962. However, the reactionary manorial lords, including monks and aristocrats, tried in every way to oppose the reforms.” |

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, Save Tibet, Cosmic Harmony, Students for a Free Tibet, Seat 61, 99th infantry battlion,

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022