UPHEAVAL IN TIBET IN THE LATE 1950s

Mao in Ramoche Monestary After the 1950 invasion of Tibet there was strong resentment by Tibetans over the Chinese occupation. After 1956 scattered uprisings occurred throughout the country. A full-scale revolt broke out in March, 1959, prompted in part by fears for the personal safety of the Dalai Lama. The Dalai Lama was able to escape to India, where he eventually established headquarters in exile. and the Chinese suppressed the rebellion. In 1965 the Tibetan Autonomous Region was formally established. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Columbia University Press |~|]

Jianglin Li, author “Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959", told the New York Times: “The crisis began on the morning of March 10, when thousands of Tibetans rallied around the Dalai Lama’s Norbulingka palace to prevent him from leaving. He had accepted an invitation to a theatrical performance at the People’s Liberation Army headquarters, but rumors that the Chinese were planning to abduct him set off general panic. Even after he canceled his excursion to mollify the demonstrators, they refused to leave and insisted on staying to guard his palace. The demonstrations included a strong outcry against Chinese rule, and China promptly labeled them an “armed insurrection,” warranting military action. About a week after the turmoil began, the Dalai Lama secretly escaped, and on March 20, Chinese troops began a concerted assault on Lhasa. After taking over the city in a matter of days, inflicting heavy casualties and damaging heritage sites, they moved quickly to consolidate control over all Tibet. [Source: Luo Siling, Sinosphere, New York Times, August 14, 2016]

When asked, how often was the Chinese military used against Tibetans, and how many Tibetan casualties were there, Li said,“We don’t have an exact tally of military encounters, since many went unrecorded. My best estimate based on official Chinese materials — public and classified — is about 15,000 in all Tibetan regions between 1956 and 1962. Precise casualty figures are hard to come by, but according to a classified Chinese military document I found in a Hong Kong library, more than 456,000 Tibetans were “annihilated” from 1956 to 1962." Li also found a correlation between self-immolations in Tibet in the 2000s and 2010s? “I think they’re a direct consequence. I’ve compared a map of the self-immolations with my map of Chinese crackdowns on Tibetans between 1956 and 1962, and there’s a striking correlation. Most of the self-immolations and the worst cases of historical repression are in the same spots in the Chinese provinces near Tibet.

See Separate Articles:TIBET IN THE 19TH AND EARLY 20TH CENTURY factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE INVASION OF TIBET IN 1950 AND ITS AFTERMATH factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE REPRESSION IN TIBET IN THE LATE 1950s AND EARLY 1960s factsanddetails.com ; SECRET CIA WAR IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ; STORY OF A MILITANT TIBETAN MONK factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947" by Tsering Shakya Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, volume 2: The Calm before the Storm: 1951-1955" by Melvyn C. Goldstein Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 3: The Storm Clouds Descend, 1955–1957" by Melvyn C. Goldstein Amazon.com; “When the Iron Bird Flies: China's Secret War in Tibet” by Jianglin Li and Dalai Lama Amazon.com; “A History of Modern Tibet, Volume 4: In the Eye of the Storm, 1957-1959" by Melvyn C. Goldstein | Amazon.com; “Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959" by Jianglin Li and Susan Wilf Amazon.com; “Flight of the Bön Monks: War, Persecution, and the Salvation of Tibet's Oldest Religion” by Harvey Rice , Jackie Cole , et al. Amazon.com; “The Struggle for Modern Tibet: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering: The Autobiography of Tashi Tsering” by Melvyn C. Goldstein , William R Siebenschuh, et al. Amazon.com; “A Poisoned Arrow: the Secret Report of the 10th Panchen Lama” By Bskal-Bzan-Tshe-Brtan Amazon.com; General History: “Tibet: A History” by Sam van Schaik Amazon.com; “A Historical Atlas of Tibet” by Karl E. Ryavec Amazon.com; “Histories of Tibet” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer , William A. McGrath, Amazon.com; “Himalaya: A Human History” by Ed Douglas, James Cameron Stewart, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet & Its History” by Hugh Richardson (1989) Amazon.com; "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein Amazon.com; “The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama” by Thomas Laird Amazon.com

China Takes Control of Tibet

Tibetans in Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu and Qinghai were already under nominal Chinese administration when the Communists took over in 1949. Actions in 1950 through the 1960s were aimed at bring Tibet proper under Beijing’s control. Robert A. F. Thurman wrote in the Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity: “The process of the Chinese takeover since 1949 unfolded in several stages. The first phase of invasion by military force, from 1949 to 1951, led to the imposition of a seventeen-point agreement for the liberation of Tibet and the military takeover of Lhasa. Second, the Chinese military rulers pretended to show support for the existing "local" Tibetan government and culture, from 1951 through 1959, but with gradual infiltration of greater numbers of troops and communist cadres into Tibet. A third phase from 1959 involved violent suppression of government and culture, mass arrests, and formation of a vast network of labor camps, with outright annexation of the whole country from 1959 through 1966. [Source: Robert A. F. Thurman, Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity, Gale Group, Inc., 2005]

Jianglin Li told the New York Times: “It was Mao’s goal from the moment he came to power” to take over Tibet. : Tibet “is strategically located,” he said in January 1950, “and we must occupy it and transform it into a people’s democracy.” He started by sending troops to invade Tibet at Chamdo in October 1950, forcing the Tibetans to sign the 17-Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet, which ceded Tibetan sovereignty to China. Next, the People’s Liberation Army marched into Lhasa in 1951, at the same time — in disregard of the Chinese promise in the agreement to leave the Tibetan sociopolitical system intact — smuggling an underground Communist Party cell into the city to build a party presence in Tibet. [Source: Luo Siling, Sinosphere, New York Times, August 14, 2016]

“Meanwhile, Mao was preparing his military and awaiting the right moment to strike. “Our time has come,” he declared in March 1959, seizing on the demonstrations in Lhasa. After conquering the city, China dissolved the Tibetan government and — under the slogan of “simultaneous battle and reform” — imposed the full Communist program throughout Tibet, culminating in the establishment of the Tibet Autonomous Region in 1965.

“Mao welcomed the campaigns to suppress minority uprisings within China’s borders as practice for war in Tibet. There were new weapons for his troops to master, to say nothing of the unfamiliar challenges of battle on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. The new weapons included 10 Tupolev TU-4 bombers, which Stalin gave Mao in 1953. Mao tested them in airstrikes at three Tibetan monasteries in Sichuan, starting with Jamchen Choekhor Ling, in Lithang. On March 29, 1956, while thousands of Chinese troops fought Tibetans at the monastery, two of the new planes were deployed. The Tibetans saw giant “birds” approach and drop some strange objects, but they had no word for airplane, or for bomb. According to Chinese records, more than 2,000 Tibetans were “annihilated” in the battle, including civilians who had sought refuge in the monastery.

Hard Times and Death in Amdo and Tibet 1958

In 1956, an uprising broke out in the Kham region of eastern Tibet. There was also violence and repression in Amdo in northern Tibet. In March 1957, the Dalai Lama returned to Lhasa from India. In 1957 and 1958, armed rebellion spread to central Tibet and major protests were held in Lhasa. Naktsang Nulo wrote “My Tibetan Childhood: When Ice Shattered Stone” about his experiences in Tibet in the late 1950s. According to the Los Angeles Review of Books: Nulo’s Tibet is a fever dream of violence. His whole family dies in his early childhood, one after another, through feuding and disease. Finally there’s just him, his older brother Japey, and his father, who abandons them. Nulo adopts a puppy whose mother has died in a trash pile. He abandons the puppy. The boys’ father returns and takes them on a caravan journey from their home in Amdo to Lhasa. Everything, even the sky and the earth, tries to kill them. Bandits ambush them in the passes; wolves by the hundreds surround them in the night and tear stray caravan members apart; deadly snow-storms sweep down over the hills and freeze them in place for days at a time. Finally the caravan gets to Lhasa, where they visit temples and get in fistfights with the monks. Then they go home again, but by now it’s late 1958, and Tibet is catching fire. What follows is an extraordinary panorama of a land at war. They ride south again, through massacred nomad camps where dogs and wolves feast on slaughtered men and livestock, past burning monasteries, poaching animals for food, as starving refugees do battle with Chinese patrols.

In a review of “My Tibetan Childhood", Kevin Carrico wrote:“In “Witness to Massacre on Our Tragic Journey through Desolate Places,” readers follow Nukho and his family on...a challenging journey to Lhasa during the “time of revolution.” In the process labeled in official-speak “social reform,” which was initiated in Tibetan areas in 1958, promises of autonomy and non-interference are followed by violence, the forced destruction of the local monastery, and the arbitrary detention of monks and laypeople. Concern about the future and a desire for his children to receive a monastic education leads Nukho’s father to guide his sons on a...journey to Lhasa...to escape death. As the narrator says, “the only way to escape was to leave my native land and wander far away”. [Source: Kevin Carrico, University of Oklahoma, MCLC Resource Center Publication, December, 2015]

After traveling for a few days, Naktsang Nulo (Nukho) write: “As we rode along the river, we began to smell something rotten. It got worse and worse, and then we saw the cause. Dogs were wandering around, eating the corpses of dead sheep and yaks, and the bodies of dead men lay scattered on both sides of the river. They were naked and dark blue. When we rode away from the river toward a cliff, we kept finding more dead people, young and old, lying on the ground.” Proceeding further up a mountain adjacent to the river, they find a group of tents whose inhabitants had been slaughtered: “The ground was completely covered by the corpses of men, women, monks, yaks, and horses . . . Wherever I looked, there was death. Then, I couldn’t look any more and turned my gaze away, up the mountain. I tried to block it out of my mind because my heart was getting more and more anxious, and my feelings were so strong. I got on the horse and rode away without looking back.

Carrico write: “The journey is long, and the desired escape is painfully and perpetually deferred. Hoping to avoid interactions with the Chinese army, the family and their fellow travelers find one chiefdom after another destroyed: monasteries ransacked, villages slaughtered, and groups of pilgrims massacred. An air of inescapable terror characterizes this section of the narrative, and finally catches up with Nukho and his family in a dramatic gun battle that leaves his father dead and the survivors in Chinese custody. As he watches vultures tear apart his father’s body, the narrator comments: “there was nowhere left to escape to”.

“The fifth section, “Torture and Imprisonment, Starvation and Survival” is by far the most powerful section of this autobiography. Readers follow the narrator into Chinese custody, where he and his brother witness the grisly torture of their companions before being placed in a nightmarish underground prison: a hole “wide enough to allow eight or nine people to sit side by side, but long enough to allow maybe 50 people to sit in the same way”. In this hole, Nukho and Japey [his brother] live with roughly 360 other prisoners who sleep, urinate, defecate, and eventually die on top of one another: each morning, guards open the hatch to remove those who died the previous night. The narrator soon learns that there were nine such holes in the Chumarleb Prison, a “living hell”, holding nearly 3,600 prisoners in this era known as the “time of revolution.”

Book: “My Tibetan Childhood: When Ice Shattered Stone” by Naktsang Nulo, translated by Angus Cargill and Sonam Lhamo (Duke University Press, 2014)

Events Leading up to March 10, 1959 Tibetan Revolt

In Lhasa, 30,000 PLA troops maintained a wary eye as refugees from the fighting in distant Kham and Amdo swelled the population by around 10,000 and formed camps on the city's perimeter. By December 1958, a revolt was simmering and the Chinese military command was threatening to bomb Lhasa and the Dalai Lama's palace if the unrest was not contained. To Lhasa's south and north-east 20,000 guerrillas and several thousand civilians had been engaging with Chinese troops. ~

On March 1, 1959, while the Dalai Lama was preoccupied with taking his Final Master of Metaphysics examination, two junior Chinese army officers visited him at the sacred Jokhang cathedral and pressed him to confirm a date on which he could attend a theatrical performance and tea at the Chinese Army Headquarters in Lhasa. The Dalai Lama replied that he would fix a date once the ceremonies had been completed This was an extraordinary occurrence for two reasons: one, the invitation was not conveyed through the Kashag (the Cabinet) as it should have been; and two, the party was not at the palace where such functions would normally have been held, but at the military headquarters - and the Dalai Lama had been asked to attend alone. [Source: Tibet Oline tibet.org~]

Dalai Lama greets protestors

On March 7, 1959, the interpreter of General Tan Kuan-sen - one of the three military leaders in Lhasa rang the Chief Official Abbot demanding the date the Dalai Lama would attend their army camp. March 10 was confirmed. On March 8, 1959— Women's Day in China— the Patriotic Women's Association was treated to a harangue by General Tan Kuan-sen in which he threatened to shell and destroy monasteries if the Khampa guerrillas refused to surrender. Rinchen Dolma (Mary) Taring wrote in her autobiography, Daughter of Tibet”: “We knew that the ordinary people of Lhasa were being driven to open rebellion against the Chinese though they would have to fight machine-gunners with their bare hands." ~

At 8:00am on March 9, 1959, two Chinese officers visited the commander of the Dalai Lama bodyguards' house and asked him to accompany them to see Brigadier Fu at the Chinese military headquarters in Lhasa. Brigadier Fu told him that on the following day there was to be no customary ceremony as the Dalai Lama moved from the Norbulinka summer palace to the army headquarters, two miles beyond. No armed bodyguard was to escort him and no Tibetan soldiers would be allowed beyond the Stone Bridge - a landmark on the perimeter of the sprawling army camp. By custom, an escort of twenty-five armed guards always accompanied the Dalai Lama and the entire city of Lhasa would line up whenever he went. Brigadier Fu told the commander of the Dalai Lama's bodyguards that under no circumstances should the Tibetan army cross the Stone bridge and the entire procedure must be kept strictly secret. The Chinese camp had always been an eyesore for the Tibetans and the fact that the Dalai Lama was now to visit it would surely create greater anxiety amongst the Tibetans. ~

Tibetan Revolt in 1959

On Tibetan New Year in 1959 a major revolt occurred. To this day no one is sure how or why it began and how widespread it was. By most accounts, it started after the Dalai Lama was forced by the Chinese government to attend a performance of a Chinese folk dance troupe at a Chinese military camp during the holiday festivities. Rumors began spreading that the Tibetan leader was going to attend without his usual phalanx of 25 bodyguards and that the Chinese planned to kidnap him.

Large crowds that had assembled anyway for the holidays gathered around Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s summer palace, and vowed to protect the Tibetan leader with their lives. The Dalai Lama had no choice but to cancel his appearance. The Chinese responded by declaring the 17-point agreement invalid. In an effort to head off violence, the Dalai Lama offered to turn himself over to the Chinese. The Chinese responded by firing two mortar shells into Norbulingka,.

On March 10, 1959, the invitation for the Dalai Lama to visit the Chinese military camp for the dance provoked 30,000 loyal Tibetans to surround the Norbulinka palace, forming an human sea of protection for their Yeshe Norbu (nickname for the Dalai Lama, meaning "Precious Jewel"). They feared he would be abducted to Beijing to attend the upcoming Chinese National Assembly. This mobilization forced the Dalai Lama to turn down the army leader's invitation. Instead he was held a prisoner of devotion. [Source: Tibet Online tibet.org ~]

On March 12, about 5,000 Tibetan women marched through the streets of Lhasa carrying banners demanding "Tibet for Tibetans" and shouting "From today Tibet is Independent". They presented an appeal for help to the Indian Consulate-General in Lhasa. Mimang Tsongdu members and their supporters had erected barricades in Lhasa's narrow streets while the Chinese militia had positioned sandbag fortifications for machine guns on the city's flat rooftops. 3000 Tibetans in Lhasa signed their willingness to join the rebels manning the valley's ring of mountains. ~

On March 15, around 3000 of the Dalai Lama's bodyguards left Lhasa to position themselves along an anticipated escape route. Khampa rebel leaders moved their most trusted men to strategic points. Stalwarts of the Tibetan Army merged with civilians to cover the chosen route. By this time the Tibetans were out-numbered 25 to 2. An estimated 30,000 to 50,000 Chinese troops wielded modern weapons and had 17 heavy guns surrounding the city. While the Chinese manned swiveling howitzers, the Tibetans were wielding cannons into position with mules. On March 16, Chinese heavy artillery was seen being moved to sites within range of Lhasa and particularly the Norbulinka. Rumours were rife of more troops being flown in from China. By nightfall Lhasa was certain that the Dalai Lama's palace was about to be shelled. ~

At 4:00pm on March 17, 1959, the Chinese fired two mortar shells at the Norbulinka. They landed short of the palace walls in a marsh. This event triggered the Dalai Lama to finally decide to leave his homeland.

PLA marching Lhasa

Dalai Lama's Escape from Tibet

In March 1959, 30,000 Tibetans surrounded Summer Palace of Norbulingka, where the Dalai Lama was staying, as 30,000 Chinese soldiers were preparing to move on the palace. Followers of the Dalai Lama were worried he might be kidnaped, imprisoned or even killed. One pro-Beijing lama was stoned to death. The Dalai Lama later wrote he felt like he was between "two volcanoes, each likely to erupt an any moment.”

The Dalai Lama decided it was time go. On the night of March 17, after mortar shells had exploded in the palace ground, the Dalai Lama disguised himself as a soldier, and flung a gun over his shoulder and fled Lhasa with 52 monks in similar disguises. His golden robe was left on a couch at Potala Palace awaiting his return.

The Dalai Lama was 24 when he left Lhasa. He traveled with 37 people, including his chamberlain, an abbot and three bodyguards. His family, monks, cabinet ministers and other bodyguards were in other small groups. Many senior monks also left. The Dalai Lama and his party crossed the Indian border at Khenzimane Pass on March 31. Pandit Nehru announced on April 3 in the Indian Parliament (Lok Sabha) that the Government of India had granted asylum to the Dalai Lama. The party took a couple of days to reach Tawang the headquaters of the West Kameng Frontier Division of the North East Frontier Agency (NEFA), now known as the Tawang District of Arunachal Pradesh. ~

See Separate Article DALAI LAMA LEADS TIBET AND ESCAPES TO INDIA factsanddetails.com

Fighting After Dalai Lama's Escape

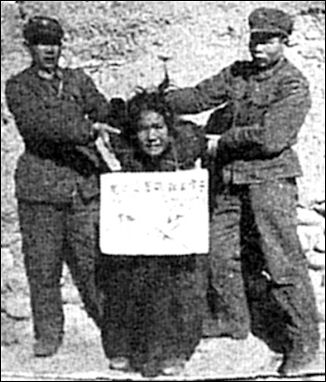

On March 19, fighting broke out in Lhasa late that night and raged for two days of hand-to-hand combat with odds stacked hopelessly against the Tibetan resistance. At 2.00 am the Chinese started shelling NorbuLingka. The Norbulinka was bombarded by 800 shells on March 21 Thousands of men, women and children camped around the palace wall were slaughtered and the homes of about 300 officials within the walls destroyed. In the aftermath 200 members of the Dalai Lama's bodyguard were disarmed and publicly machine-gunned. Lhasa's major monasteries, Gaden, Sera and Drepung were shelled -the latter two beyond repair - and monastic treasures and precious scriptures destroyed. Thousands of their monks were either killed on the spot, transported to the city to work as slave labour, or deported. In house-to-house searches the residents of any homes harbouring arms were dragged out and shot on the spot. Over 86,000 Tibetans in central Tibet were killed by the Chinese during this period.

According to China Channel: When his disappearance was discovered two days later, Lhasa erupted. There were some striking images amid the atrocity: the elite monks of the Higher Tantric College formally renounced their Buddhist vows, took up rifles, and joined the fight; the Tibetan Medical College on Chakpori Hill overlooking the city was shelled into rubble by PLA artillery; a massacre in the courtyard of the ancient Ramoché Temple; house-to-house fighting through the center of Lhasa; and finally a last stand at the Jokhang Temple, Tibet’s holy-of-holies, where the encircled defenders surrendered at dawn on March 20, as the city burned around them. [Source: China Channel, LARB, November 20, 2020]

On March 28, 1959, the Chinese Communist Party announced the creation of the Tibet Autonomous Region and dissolved the old Tibetan government.The unsuccessful uprising lead to a severe crackdown by the Chinese. China abolished the autonomous Tibetan government and the Dalai Lama and and tens of thousands of his followers were chased into exile.

Chinese Response to the 1959 Tibetan Revolt

Chinese forces crushed the rebellion. Two days after the Dalai Lama escaped from Lhasa, the Communists closed down the Tibetan government, seized land and bombed Potala palace, Sera Monastery and the medical college of Changp Ri. Chinese snipers picked off protestors, some with Molotov cocktails, in the streets. When more 10,000 protestor sought refuge in the Jokhang Temple, it too was bombed. By some estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Tibetans were killed in three days of violence. After the revolt, the Chinese closed the passes to travel in and out of Tibet, shut down all of Tibet’s monasteries, and threw thousands of people into prisons and labor camps. After the suppression campaign began Mao said, "In three months these people will believe in communism."

The Chinese used the rebellion as a pretext for ending Tibetan autonomy, imposing martial law, and instituting severe political and religious persecution. The Panchen Lama, who had accepted Chinese sponsorship, acceded to the spiritual leadership of Tibet. The Chinese adopted brutal repressive measures, provoking charges from the Dalai Lama of genocide. Landholdings were seized, the lamaseries were virtually emptied, and thousands of monks were forced to find other work. The Panchen Lama was deposed in 1964 after making statements supporting the Dalai Lama; he was replaced by a secular Tibetan leader. In 1962, China launched attacks along the Indian-Tibetan border to consolidate territories it claimed had been wrongly given to India by the British McMahon Commission in 1914. Following a cease-fire, Chinese troops withdrew behind the disputed line in the east but continued to occupy part of Ladakh in Kashmir. Some border areas are still in dispute. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Columbia University Press |~|]

Chinese Take on the 1959 Tibetan Revolt

According to the Chinese government: “In March 1959, the former Tibetan local government and the reactionary clique in the upper strata tore up the 17-article agreement under the pretext of "safeguarding national interests" and "defending religion" and staged an armed rebellion in Lhasa. They instigated rebel forces in different places to attack Communist Party and government offices and kill people, while abducting the Dalai Lama and compelling people to flee the country. [Source: China.org china.org |]

Tibet in 1958 after

the Chinese took it over

“The State Council, acting upon the request of the Tibetan people and patriots in the upper strata, disbanded the Tibet local government (Kasha) and empowered the Preparatory Committee for the Tibet Autonomous Region to exercise the functions and powers of the local government. With the active support of the Tibetan laboring people and patriots of all strata, the People's Liberation Army soon put down the rebellion. |

“The Preparatory Committee began carrying out democratic reforms while fighting the rebels. In the farming areas, a campaign was launched against rebellion, unpaid corvee service and slavery and for the reduction of rent and interest. In the pastoral areas, a similar campaign against the three evils was coupled with the implementation of the policy of mutual benefit to herdsmen and herd owners. All the means of production belonging to those serf owners and their agents who participated in the rebellion were confiscated, and the serfs who rented land from them were entitled to keep all their harvests for that particular year. All the debts laboring people owed to them were abolished. The means of production belonging to those serf owners and their agents who did not participate in the rebellion was not confiscated but bought over by the state. Rent for their land was reduced and all old debts owed by serfs were abolished. In the monasteries, the feudal system of exploitation and oppression was abolished and democratic management was instituted.” |

“Land and other means of production including animals, farm implements and houses confiscated or bought by the state were redistributed fairly and reasonably among the poor serfs, serf owners and their agents, with priority given to the first group. In livestock breeding areas, while the animals owned by manorial lords and herd owners who participated in the rebellion were confiscated and distributed among the herdsmen, no struggle was waged against those who did not participate, their stock was not redistributed, and no class differentiation was made. Instead, the policy of mutual benefit to both herd owners and herdsmen was implemented. Under the leadership of the Communist Party, the million serfs overthrew the cruel system of feudal serfdom and abolished the regulations and contracts that had condemned them to exploitation and oppression for generations. They received land, domestic animals, farm implements and houses and were emancipated politically. In September 1965, the Tibet Autonomous Region was officially established. The Tibetans have since embarked on a road of socialist transformation, cautiously but steadily.” |

Separatists and the C.I.A. in Tibet

The Khams (Tibetans from the Kham province of Tibet) launched a separatist movement in the mid 1950s after their homeland was annexed by the Chinese and added to Sichuan province and they we ordered to turn in their guns. Many Khams wore pictures of the Dalai Lama in amulets worn around their necks which they believed would protect them from bullets. For the Khams the Buddhist love of all living things did not extend to the Chinese. One guerilla in the film "Shadow Circus: The CIA in Tibet" said, “When we kill an animal, we say a prayer, But when we killed Chinese, no prayer came to our lips."

The C.I.A. agreed to help the Khams by training them in guerilla warfare and helping them run operations in Tibet against the Chinese. The lord chamberlain for the Dalai Lama and other high official were very enthusiastic about the operation. The Dalai Lama himself was skeptical about its aims and its chances of success. The operation, codenamed ST CIRCUS, was by all accounts a disaster. [Source: Melinda Lu, Newsweek, April 19, 1999]

After the fighting in Tibet intensified, many Tibetans fled to a refugee camp near Darjeling, India, where the C.I.A., recruited fighters. The first of these recruits were trained by the C.I.A. and parachuted into Tibet from B-17s that took off from an airstrip near Dhaka in present-day Bangladesh. Outfit with communication equipment, they met up with resistance fighters near Lhasa and helped them coordinate their operations.

See Separate Article SECRET CIA WAR IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, Save Tibet, Cosmic Harmony, Students for a Free Tibet, Seat 61, 99th infantry battlion,

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022