XINJIANG RIOTS IN 2009

In July 2009 bloody riots broke out in Urumqi, a city of 2.3 million in Xinjiang, that, according to the Chinese government, resulted in the deaths of 197 people — 137 Han and 46 Uighurs and one Muslim Hui — and injured 1,700. This was more than were officially killed and injured in the Tibet riots in 2008. The riots were the bloodiest known incident in China since Tiananmen Square in 1989.

There had been demonstrations and terrorist attacks in the past in Xinjiang but not the spontaneous and bloody unleashing of anger and frustration that occurred this time. Uighur expert Dru Gladney at Pomona College told AP, “We haven’t had anything like this, really, ever. It really gives strong evidence of widespread unrest and discontentment.”

There were many parallels between the riots in Xinjiang and the ones a year earlier in Tibet. Both Tibetans and Uighurs seemed frustrated by the same things?unfair treatment, lack of jobs and opportunities, growing migrations of Han Chinese and restrictions and crackdowns on their freedoms, religions and way of life. In both Urumqi and Lhasa, protests that began peacefully quickly became violent and out of control with the brunt of the wrath of the mobs directed at the Han Chinese. In both cases the violence seemed to be a spontaneous outbursts rather than coordinated, planned attacks even though the Chinese government said otherwise, blaming outsiders.

Most of the violence occurred in Urumqi although some violence was reported in Kashgar and other Xinjiang cities. People’s Square in central Urumqi served as a gathering area for both Uighurs and Han Chinese, who then spread from there to carry out attacks in other parts of the city.

The government described the violence as the worst riots since the foundation of the People's Republic in 1949. Historians said it was the worst case of ethnic violence since the end of the Cultural Revolution. One Chinese official told the Washington Post, the “riots left a huge psychic trauma and the minds of many people of all ethnicities, This fully reflects the great harm done to the Chinese autonomous region by “splittist” forces.”

Much of the information on the riots came from official Chinese sources. In the official casualty figures by the Chinese government, three quarters if the dead were Han Chinese. Uighur groups said that more than 400 demonstrators were killed in Urumqi and between 1,000 and 3,000 Uighurs were killed throughout Xinjiang.

See Separate Articles: Uyghurs and Xinjiang factsanddetails.com; UYGHURS AND THEIR HISTORY, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION factsanddetails.com; XINJIANG Factsanddetails.com/China ; XINJIANG LATER HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/China ; UYGHUR-RELATED PROTESTS, RIOTS AND VIOLENCE IN XINJIANG IN THE 2010s factsanddetails.com ; TERRORISM IN XINJIANG factsanddetails.com ; TERRORIST GROUPS IN XINJIANG (MOSTLY GONE OR OVERHYPED) factsanddetails.com ; TERRORIST ATTACKS IN XINJIANG factsanddetails.com ; UYGHUR-RELATED TERRORIST ATTACKS IN 2013-2014: TIANANMEN SQUARE, GUANGZHOU AND SMALLER ATTACKS factsanddetails.com ; KUNMING ATTACK IN MARCH 2014 KILLS 31 factsanddetails.com ; URUMQI TERRORIST ATTACKS IN APRIL 2014 KILL 42 factsanddetails.com ; COMBATING TERRORISM IN XINJIANG factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Xinjiang Wikipedia Article Wikipedia Xinjiang Photos Synaptic Synaptic ; Maps of Xinjiang: chinamaps.org Uyghur Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Uyghur Photo site uyghur.50megs.com ; Uyghur News uyghurnews.com ; Uyghur Photos smugmug.com ;Islam.net Islam.net ; Uyghur Human Rights Groups ; World Uyghur Congress uyghurcongress.org ; Uyghur American Association uyghuramerican.org ; Uyghur Human Rights Project uhrp.org ; Muslims in China Islam in China islaminchina.wordpress.com ; Claude Pickens Collection harvard.edu/libraries ; Islam Awareness islamawareness.net ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ethnic Conflict and Protest in Tibet and Xinjiang: Unrest in China's West” by Ben Hillman and Gray Tuttle Amazon.com; “Xinjiang and the Modern Chinese State” by Justin M. Jacobs Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; “Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland” by S. Frederick Starr Amazon.com; “China's Forgotten People: Xinjiang, Terror and the Chinese State” by Nick Holdstock Amazon.com; “China’s Soft War on Terror “ by Tianyang Liu Amazon.com; “Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism in China: Domestic and Foreign Policy Dimensions” by Michael Clarke Amazon.com; “On Terrorism: Chinese Perspectives” by Wang Yizhou and Zhang Yidan Amazon.com; “China's War on Terrorism: Counter-Insurgency, Politics and Internal Security” by Martin I. Wayne Amazon.com

Trigger for Xinjiang Riots in 2009

The riots were triggered by a brawl between Han Chinese and Uighurs that took place more than 3,000 kilometers from Urumqi at the Xuri Toy Factory in Shaoguan in Guangdong Province in southern China that left two Uighurs dead and 118 injured, including 13 who were seriously hurt.

The brawl began after a Han Chinese girls entered a factory dormitory where Uighur workers from Xinjiang were staying, leading to a rumor that she had been sexually assaulted. According to Radio Free Asia interviews with Uighur workers, a mob of Chinese workers and gang members from the area stormed into the dormitory beating Uighurs and hacking them with a machete.

Uighurs say that many more than two Uighurs were killed. Graphic photographs widely circulated on the Internet showed at least a half dozen of dead Uighurs, with Han Chinese standing over them with their arms raised in victory.Many economists, Han Chinese and Uighur alike, saw the roots of the violence in high rates of unemployment among young Uighur men.

Ten days later there were demonstrations and riots in Urumqi.

Toy Factory Brawl Before Xinjiang Riots

The fight, at the Xuri (Early Light) Toy Factory in Shaoguan City, was incited by rumors that a group of Muslim Uighurs had raped two Han Chinese women. It raged at a factory dormitory through the early-morning hours of June 26, eventually leaving two Uighur men dead and, by some accounts, about 120 other people injured, most of them Uighurs, and 60 of these were hospitalized. [Source: David Barboza, New York Times, October 10, 2009]

The police said no woman was raped. The government said the fight was caused by a misunderstanding involving a woman who accidentally ventured into a dormitory room of Uighur men. According to the government’s account, a Han Chinese man later posted reports of rape on the Internet, setting off a bloody showdown. The Uighur workers who were killed and injured were mostly part of a group of 800 Uighur workers imported to the Guangdong toy factory as part of a government affirmative-action program. This angered Han workers who were not given some of the same benefits of the Uighurs such as free room and board.

Andrew Jacobs wrote in New York Times, “The first batch of Uighurs, 40 young men and women from the far western region of Xinjiang, arrived at the Early Light Toy Factory here in May, bringing their buoyant music and speaking a language that was incomprehensible to their fellow Han Chinese workers. “We exchanged cigarettes and smiled at one another, but we couldn’t really communicate, said Gu Yunku, a 29-year-old Han assembly line worker....’still, they seemed shy and kind. There was something romantic about them.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times July 16, 2009]

“The mutual good will was fleeting. By June, as the Uighur contingent rose to 800, all recruited from an impoverished rural county not far from China’s border with Tajikistan, disparaging chatter began to circulate. Taxi drivers traded stories about the wild gazes and gruff manners of the Uighurs. Store owners claimed that Uighur women were prone to shoplifting. More ominously, tales of sexually aggressive Uighur men began to spread among the factory’s 16,000 Han workers.”

‘shortly before midnight on June 25, a few days after an anonymous Internet posting claimed that six Uighur men had raped two Han women, the suspicions boiled over into bloodshed. During a four-hour melee (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fjEHEpTUF3E) in a walkway between factory dormitories, Han and Uighur workers bludgeoned one another with fire extinguishers, paving stones and lengths of steel shorn from bed frames.”

“By dawn, when the police finally intervened, two Uighur men had been fatally wounded. People were so vicious, they just kept beating the dead bodies, said one man who witnessed the fighting, which he said involved more than a thousand workers.”

Reasons Behind the Toy Factory Rampage

In the government’s version of events, the factory clash was the simple product of false rumors, posted on the Internet by a disgruntled former worker who has since been arrested. Shaoguan officials, who said that the rape allegations were untrue, contended that the violence at the toy factory was used by outsiders to fan ethnic hatred and promote Xinjiang separatism. The issue between Han and Uighur people is like an issue between husband and wife, Chen Qihua, vice director of the Shaoguan Foreign Affairs Office, said in an interview. We have our quarrels, but in the end, we are like one family.

Li Qiang, the executive director of China Labor Watch, an advocacy group based in New York that has studied the Shaoguan toy factory, has a different view. He told the New York Times the stress of low pay, long hours and numbingly repetitive work exacerbated deeply held mistrust between the Han and the Muslim Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking minority that has long resented Chinese rule. The government doesn’t really understand these ethnic problems, and they certainly don’t know how to resolve them, Li said.

“A few days later, the authorities added another wrinkle to the story, saying that the fight was prompted by a misunderstanding after a 19-year-old female worker accidentally stumbled into a dormitory room of Uighur men. The woman, Huang Cuilian, told the state news media that she screamed and ran off when the men stamped their feet in a threatening manner. When Huang, accompanied by factory guards, returned to confront the men, the standoff quickly escalated.”

The Uighurs who worked at the Shaoguan toy factory all came from Shufu County outside Kashgar. After the riot they were sequestered at an industrial park not far from the toy factory. The government of Guangdong Province, where Shaoguan is located, and the factory would provide them employment at a separate plant. Officials at Early Light, a Hong Kong company that is the largest toy maker in the world, declined to comment. If we weren’t so poor, our children wouldn’t have to take work so far from home, said Akhdar, a 67-year-old man who, like many others interviewed, refused to give his full name for fear of reprisals from the authorities.

After the Toy Factory Brawl

On July 5, after reports of the brawl spread to Xinjiang, where most of the country’s Uighur Muslims live, demonstrations and riots broke out. Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, told Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan: “After the incident in Shaoguan, Guangdong, I felt that something big would happen, that blood would flow. Before the Shaoguan incident, there were already seeds of a disturbance in Xinjiang.” Uighurs were upset about .bilingual education, and government arrangements to send Uighurs away to work. “These two policies were strongly opposed by many Uyghur cadres, but anyone who dared to say “no” was immediately punished.”[Source: Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan interview of Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist, blogger, and AIDS activist , siweiluozi.blogspot.com ]

“Looking at it from today, it was certainly organized. As for premeditated, between June 26 and July 5, there was already plenty of time for that. But the most crucial thing was that the government did not take prompt measures to prevent deterioration of the situation. On July 4, I was continually listening to Radio Free Asia and the Voice of America. On that day, World Uyghur Congress President Rebiya [Kadeer] and others were truly a bit out of the ordinary on that day, with nearly all of the leaders going on the air to speak.”

Willy Lam wrote in China Brief, “Beijing and Xinjiang security officers have claimed that they had in late June and early July intercepted messages sent by the World Uighur Congress to underground XAR groups with the purpose of instigating them to engineer something really big on July 5. And in a press conference last weekend, Bekri admitted that the authorities were aware of relevant information about the protests. Bekri also disclosed that on the fateful day, government officials were on hand to dissuade college students from holding demonstrations. Yet despite the formidable military and police presence in the XAR capital, the authorities were unable to prevent the political rally from degenerating into a bloody, no-holds-barred slugfest.” [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, July 23 2009]

Beginning of the Riots in Xinjiang

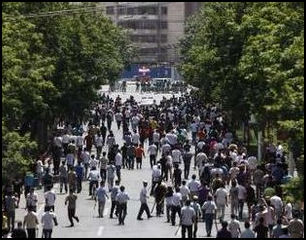

The riots broke out on July 5 after police stopped an initially peaceful protest of 1,000 to 3,000 people, mostly Uigur youths, The protestors were demanding an investigation into the factory brawl in southern China. There were widespread views among Uighurs that government didn’t care about them or their concerns.

Heyrat Niyaz, an Uyghur journalist and blogger, told Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan: “I believe that the July 5 incident was organized by Hizb-ut-Tahrir al-Islami [ILP, Islamic Liberation Party], an illegal religious organization that has spread extremely quickly in southern Xinjiang. On July 5, I was on Xinhua South Road watching as rioters smashed and looted. More than 100 people gathered and dispersed in an extremely organized manner, all of them wearing athletic shoes. Based on their accents, most were from the area around Kashgar and Hotan, but I did not see any of them carrying knives.” I suspect they were from the ILP because of their slogans. The rioters were shouting “Han get out!” [and] “Kill the Han!” Other than these [slogans], there was also “We want to establish an Islamic country and strictly implement Islamic law.” One of the main goals of the ILP is to restore the combined political and religious authority of the Islamic state and strictly implement Islamic law; it is a fundamentalist branch.” [Source: Hong Kong newsweekly Yazhou Zhoukan interview of Heyrat Niyaz]

Edward Wong wrote in the York Times, “The rioting broke out in a large market area of Urumqi...and lasted for several hours before riot police officers and paramilitary or military troops locked down the Uighur quarter of the city, according to witnesses and photographs of the riot. The clashes reached their peak in a Uighur neighborhood centered in a warren of narrow alleyways, food markets and a large shopping area called the Grand Bazaar or the Erdaoqiao (pronounced ar-DOW-chyow) Market...At least 1,000 rioters took to the streets, stoning the police and setting vehicles on fire. Plumes of smoke billowed into the sky, while police officers used fire hoses and batons to beat back rioters and detained Uighurs who appeared to be leading the protest, witnesses said.” [ ”[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 6, 2009]

“The clashes...began when the police confronted a protest march held by Uighurs to demand a full government investigation of a brawl between Uighur and Han workers that erupted in Guangdong Province...There was also a rumor circulating on Sunday in Urumqi that a Han man had killed a Uighur in the city earlier in the day, said Adam Grode, an English teacher living in the neighborhood where the rioting took place.”

State television showed images of protesters attacking and kicking people on the ground. In one image two men, appearing to be Uighurs, were shown kicking a Han woman as she lay on a sidewalk. Other people, who appeared to be Han Chinese, sat dazed with blood pouring down their faces. One images showed a bloodied man trying to stand tup. Another showed two girls with blood on their hands comforting each other. There was also footage of a crowds of men pushing over a police car, smashing its windows and throwing stones at it. Early reports said 260 vehicles were attacked or set on fire and 203 houses were damaged on the first day of rioting.

A few weeks after the riots the Chinese government said that Chinese police killed 12 people, a rare acknowledgment that the government had a direct hand in the violence. Xinjiang governor Nur Bekri said that police shot “mobsters” after firing warning shots but did not identify the ethnicity of the victims. “The police showed as much restraint as possible during the unrest,” he said, adding that many police were injured and one was killed.

Eyewitness Reports of the Xinjiang Riots

One woman who participated in the demonstrations, told National Geographic young people gathered peacefully in Urumqi’s public square, they shouted, “Uighur! Uighur! Uighur!,” Then something happened. It is not clear what. Uighurs said the police sparked the rioting by shooting at peaceful protestors as they tried to stop the demonstration and disperse the crowd. The crowds refused to disperse and overturned barricades and attacked vehicles, and houses and clashed with police.

The crowds then scattered throughout Urumqi. Uighurs protestors attacked, looted and set fire to Han businesses. They smashed windows, burned cars, and attacked Han Chinese. In area f Han-owned car dealerships windows were smashed and brand new cars were overturned.

Adam Grode, an English teacher living in the neighborhood where the rioting took place, who watched the rioting at its height.” He ‘said he did not see lethal fighting, though he said he did see what appeared to be Uighurs shoving or kicking a few Han Chinese. Images of the rioting on state television showed some bloody people lying in the streets and cars burning. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 6, 2009]

“This is just crazy,” Grode told the New York Times. “There was a lot of tear gas in the streets, and I almost couldn’t get back to my apartment. There’s a huge police presence.” Grode said he saw a few Han civilians being harassed by Uighurs. Rumors of Uighurs attacking Han Chinese spread quickly through parts of Urumqi, adding to the panic. A worker at the Texas Restaurant, a few hundred yards from the site of the rioting, said her manager had urged the restaurant workers to stay inside.

Grode, who lives in an apartment in the the Erdaoqiao area, said he went outside when he first heard commotion around 6 p.m. “He saw hundreds of Uighurs in the streets; that quickly swelled to more than 1,000, he said. Police officers soon arrived. Around 7 p.m., protesters began hurling rocks and vegetables from the market at the police, Grode said. Traffic ground to a halt. An hour later, as the riot surged toward the center of the market, troops in green uniforms and full riot gear showed up, as did armored vehicles. Chinese government officials often deploy the People’s Armed Police, a paramilitary force, to quell riots. By midnight, Grode said, some of the armored vehicles had begun to leave, but bursts of gunfire could still be heard.”

“All around the Erdaoqiao area is very very tense, said a taxi driver who works near the market, but refused to be identified. The area is deserted, like you?re driving around in the wee hours of the morning. This morning when I was driving around, I saw three or four burnt-out cars. There’s ash and glass all over the place. Buses, taxis, vans, all with their windows smashed in, empty.”

Family Killed by Uighurs During the Xinjiang Riots

A Han family that ran a grocery store all died when Uighur rioters set fire to the store. Four bodies were found. One woman was missing. Some think she may have been dragged away by the rioters and murdered. So shocking was the family tragedy that one newspaper carried a special report on it, Police have confirmed the killings.[Source: Jane Macartney, The Times, July 7, 2009]

A Han neighbor told the Times of London: “We saw hundreds of Uighurs running down the street on the afternoon of July 5. About ten suddenly rushed into the store. They began to hit the people inside, even the old mother, with bricks and stones. They tried to runoutside. Then they were dragged back inside. “There were terrible screams. Just wordless screams. But then very quickly they fell silent.”

She said that the son tried to hide in a chicken coop but was dragged out and his head was cut off. All the victims were left to burn inside the building. The corpses of the boy and his father were found beheaded. Mr Yu said: “Even the 84-year-old mother was stoned and then burnt. It was terrible, terrible. So cruel.”

The brother-in-law of the grocery store owner said the owner moved from central Henan province a decade earlier to run a successful business in a district with a high proportion of ethnic Uighur residents. “Perhaps they were jealous of his success. They clearly targeted the family. It looked as if they had decided in advance to pick on my sister. The police are pursuing the case and they have made some arrests,” said Mr Yu.

An Uighur woman told the New York Times, “It was horrible for everyone.” She said she spent the night cowering at the back of her grocery store with her 10-year-old daughter. “The rioters were not from here. Our people would not behave so brutally.”

Police Crackdowns During the Xinjiang Riots in 2009

Police and paramilitary troops were dispatched. Helicopters dropped leaflets calling for calm. A curfew that ran from 9:00pm to 8:00am was imposed. Groups of 30 police marched through the streets chanting slogans encouraging ethnic unity. Vehicle cruised around blaring public announcements in the Uighur language that exiled Uighur leader Rebiya Kadeer instigated the riots.

Hundreds of troops camped out in the central part of Urumqi. Shops were shuddered. Mosque was closed during Friday prayers on the ground that the gathering would used to organized protests and attacks. The area around People’s Square was carefully guarded. Military helicopters flew overhead. Mobile phone service was cut off.

The Chinese authorities acknowledged shooting dead 12 Uighur rioters in Xinjiang this month, in a rare acknowledgement of deaths at the hands of security forces. Nuer Baikeli, governor of the north-western region, said police had exercised “the greatest restraint” as they sought to suppress riots in the capital Urumqi. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian July 18, 2009]

The governor said police first fired into the air in warning and then shot dead the armed Uighurs as they attacked civilians and ransacked shops. Three rioters died on the spot and the others on their way to or in hospital. “In any country ruled by law, the use of force is necessary to protect the interest of the people and stop violent crime. This is the duty of policemen,” Baikeli told a small group of reporters, including Reuters. He added: “Most of the victims were innocent civilians. The violent elements were most inhuman, barbaric ... extremely vicious, unscrupulous and brutal.” Most victims had been bludgeoned to death with bricks and iron rods,” he said.

Police Crackdowns on Uighurs During the Xinjiang Riots in 2009

Han retaliation A fierce crackdown ensued after reports began circulating that 100 Uighurs, armed with wooden staves, were roaming the streets intent on attacking local party officials. Relaying reports given to her by local Uighurs Jane Macartney wrote in the Times of London, “Men hid in their houses; some were pulled out from under their beds during a police search...Police entered the crowded, slum-like courtyards and ordered the men out. They checked their identity cards. Many were taken out on the main road, ordered to strip to their underpants and lie down on the ground with their hands behind their heads...Once all the suspects had been detained, they were loaded into trucks and driven off.”

Uighurs, many of them women, protested the arrest of relatives. In some cases the faced off with police, wailing and waving the identity cards of their husbands, brothers and sons. One woman told Reuters, “My husband was taken away...by police. They didn’t say why. They just took him away.”

Tursun Gul, an Uighur woman whose husband and four brothers were taken away by police, confronted police demanding they tell her where her husband was. After joining a crowd of 300 women who had rushed into the street she stepped out from the crowd and walked straight toward a row of advancing armored personnel carriers and forced them to back off. It was moment similar to one when the lone man faced down the tanks at Tiananmen Square in 1989. “I thought if they beat me or killed me there were more people behind me who would take my place,” Gul told the Times of London, “I told police that we wanted freedom and a peaceful life. Just let my five men go.”

“An ethnic Han woman who lives in an apartment near the Erdaoqiao market said the streets were effectively under a police curfew. “The area is completely closed off to traffic. The people outside can’t come in, we can’t go out, she said. When something big happens, it’s best to stay home. Nothing’s open outside anyways, no stores are open. where are you going to go?... What they should do is crack down with a lot of force at first, so the situation doesn’t get worse. So it doesn’t drag out like in Tibet, she added. Their mind is very simple. If you crack down on one, you?ll scare all of them. The government should come down harder.”[Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 6, 2009]

“Dozens of Uighur men were led into police stations on Sunday evening with their hands behind their backs and shirts pulled over their heads, one witness said. Early Monday, the local government announced a curfew banning all traffic in the city until 8 p.m.”

Han Retaliation to Xinjiang Riots in 2009

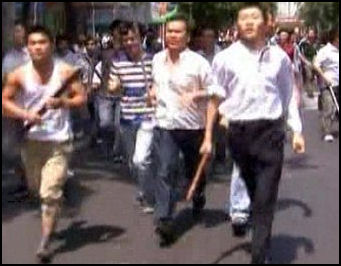

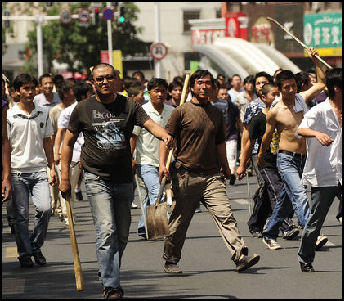

Han retaliation On July 7th, two days after the initial riots, Han Chinese in Urumqi, demanding revenge, took to the streets wielding machetes, steel pipes, cleavers, bricks, chains, poles and other weapons and staged attacks in Uighur neighborhoods. Many Han said they were responding to rumors of further Uighur attacks on Han. “They attacked us. Now it's our turn to attack them,” one protester told Reuters. Another said: “We're here to demand security for ourselves. They killed children in cold blood.”

Police attempted to disperse today's mob with teargas as they headed towards a predominantly Uighur area, but many were still on the streets armed with whatever came to hand: wooden staves, iron bars, metal chains, numchuks, shovels and axes. Rioters smashed Uighur restaurants, threw rocks at a mosque and threatened residents of Uighur areas, although moderates in the crowd attempted to restrain them. “It's your time to suffer,” they shouted at some of the five- and six-storey apartment blocks lining Xinfu Road. [Source:Tania Branigan, The Guardian, July 7, 2009]

For at least three days Han Chinese roamed the streets of Urumqi. The fact that police and security forces were out in full force was not enough to deter vengeful Han from hunting down Uighurs and destroyed shops owned by Uighurs. One Uighur holed up in her apartment for a week told the New York Times, “This is our homeland. Where are we going to go if we leave this city? Where are we going to go?”

In some places Han and Uighurs clashed face to face and threw rock and brick and other objects at one another while Han shouted “attack Uighurs.” Police fired tear gas to disperse he crowds. One Han man who participated in the battle told Reuters, “They attacked us. Now it’s our turn to attack them.”

A respectable-looking middle-class woman carried a plank with a nail sticking out of it; a young woman in a colorful, patterned top and white diamante mules clutched a piece of metal pipe. A father held his young son in one hand and a length of wood in the other. “We just want to defend our stuff,” said one man. “They were using everything for weapons, like bricks, sticks and cleavers,” said Ma, an employee at a nearby fastfood restaurant. “Whenever the rioters saw someone on the street, they would ask 'are you a Uighur?' If they kept silent or couldn't answer in the Uighur language, they would get beaten or killed.” [Op Cit. Guardian]

Few people seemed to know where rumors of further attacks had come from, but witnesses told Reuters that earlier in the day groups of around 10 Uighur men armed with bricks and knives had attacked Han Chinese passersby and shop owners until police arrived." At one point a Han mob began marching towards the Xinjiang regional government offices, saying the government was too weak, “Now its time to go to the government,” a protester named Zhang said.

One Uighur businessman told AP, “We don’t believed this. They need to tell the Han to retreat. We?re going to stay here to protect our homes.” The leader of a group of 10 Uighur men said, “We?re just protecting our homes, We?re not planning a counterattack.”

Police Response to Han Attacks on Uighurs During Xinjiang Riots

Large groups of paramilitary police?that including both Han and Uighurs — guarded the main road to Uighur neighborhoods. Most were armed with shields and batons. Some had assault rifles fixed with bayonets. Leaflets dropped form helicopters pleaded with people to stay at home. The police used their shields to push Han protesters away but in some cases protesters briefly broke through the police lines. At this point security forces focused their energy on cooling down the Han Chinese mobs. One Han Chinese man told AP, “the government told us not to get involved in any kind of violence. They?ve been broadcasting this on the radio and they even drove through neighborhoods with speakers telling people not to carry weapons.”

Authorities were initially slow to react as large numbers of Han Chinese gathered on the streets around the People's Square in the center of the city from around 2pm. But the city's Communist party chief, Li Zhi, later took to the streets, using a bullhorn from the top of a police four-wheel drive to beg protesters to calm down and go home. Police stopped the crowd entering an Uighur neighborhood, but even teargas could not disperse them. Journalists who tried to follow the crowd were bundled away from the scene “for their own safety?, as protesters turned angrily on some cameramen, shoving and shouting at them.

Elsewhere in the capital, officers pleaded with gangs to go home. One told protesters holding wooden and metal bars: “Please stand away. We are a nation united.” A man replied: “Our brothers and sisters have been bloodied.” Another officer told the mob: “We need to protect the law. Please retreat. Please trust us.”

Banks closed their doors and staff crouched inside, some holding staves, while hotel staff taped up windows. Earlier in the day Chinese armed police and Uighurs clashed as residents erupted into protests during an official media tour of the riot zone, in the face of hundreds of officers. Women in the marketplace burst into wailing and chanting as foreign reporters arrived, complaining that police had taken away Uighur men.

Some Order is Restored After Xinjiang Riots in 2009

Some calm was restored as more security forces from the outside began arriving in Urumqi. According to AP, “Crowds of Han Chinese...cheered as trucks full of police and covered by banners reading “We must defeat the terrorists” and “Oppose ethnic separatism and hatred” rumbled by...Uighurs became more fearful about talking to reporters.”

But things were still very tense. A Han supermarket owner told AFP a week after the initial riot, “It’s still very dangerous.” When asked about entering the Uighur part of town he said, “I had friends who went there yesterday who were threatened by Uighurs and they had to run out of there.” One Han from Jiangsu Province who arrived in Urumqi after he riots told the Los Angeles Times, “I head everything was great here, but when I got in, everything was scary.” Around thus time police shot dead two Uighurs in renewed violence

There calls by ordinary Uighurs and Han for peace. Tusun Gul told the Times of London, “The Han don’t hate the Uighurs and the Uighurs don’t hate the Han. I have sympathy for the Han people who were killed. We need to have ethnic unity.”

Death of Uighur Demonstrator

In Urumqi about a week after the riots began, Matthew Teague wrote in National Geographic, “Han security forces stood in ranks along every street in the city’s Uygur quarter. They bristled with riot gear and automatic weapons. The only sound came from loudspeakers mounted on trucks that trawled the market streets, broadcasting the good news of ethnic harmony. If Urumqi had an edge of unrest...It was sheathed in silence.”

“Now three men stepped from a mosque holding what looked like wooden sticks. One wore a blue shirt..All three walked with peculiar long strides and waved their sticks overhead...Once across the street, they burst into a run, heading towards a groups of armed Chinese...The details of the next moment?the range of the running man, his shirt billowing behind him, the strange coolness of the air?were etched by a sound: a gunshot. But the three Uygurs did not stop in the face of destruction. They tilted towards it.”

“I watched them stride up the street and back, then run at the Chinese forces. First came the single shot, which missed. The Uygurs continued their charge, and I realized the running men with their rusted swords did not expect to prevail. They expected to die...A moment later another officer released a bust of automatic fire. The lead Uighur?the man in the flowing blue shirt?fell with the sudden slackness of a thrown rag doll. His body hit the pavement, but the momentum of his sprint sent him tumbling, and his feet flew up and over his head.”

The remaining two Uygurs ran into the street, and the scene became three-dimensional, with bullets flying in my direction. I ran into a nearby building and found myself in the lobby of an enormous departments store. People pressed themselves into corners and behind clothing displays; women wailed, and two men improvised a door lock by shoving a metal bar through the door’s handles. Beyond the building’s glass doors...all three of the Uygur men now lay in the streets, one injured and two dead. Soldiers, police and plain clothes security officers were firing upwards into the windows of surrounding buildings.”

Responsibility for Xinjiang Riots in 2009

Beijing said the riots had nothing to do with China’s ethnic policies or the migration of Han Chinese to Xinjiang. Authorities blame “separatists” for the riots and placed direct blame on Rebiya Kadeer for fomenting the violence. Xinjiang governor Nur Bekri said, “Rebiya had phone conversations with people in China on July 5 in order to incite and Web sites...were used to orchestrate the incitement and spread propaganda.” A letter reportedly signed by her son and daughter blamed her for starting the riots. Kadeer denied that her children would sign such a letter unless they were coerced to.

State television said, “This was an incident remotely controlled, directed and incited from abroad, and executed inside the country. It was a planned and organized violent crime.” As evidence that the riots were coordinated by outriders, Beijing pointed to the fact that some of the attacks occurred at the same time as demonstrations against Chinese consulates in Europe and the United States.

Some think that riots a year earlier in Tibet had an influence on Xinjiang. Rohan Gunaratna, a Singapore-based terrorism expert, told AP, “One protest movement will influence another protest movement. To a significant extent, the protest in Tibet has influenced the protests in Xinjiang.”

Chinese Government Response to the Xinjiang Crisis

After the riots the mayor of Urumqi said, “It’s not an ethnic issue nor a religious issued but a battle of life and death...a political battle that’s fierce and of blood and fire.” Han residents of Urumqi accused the government of failing to protect them from the violence and of withholding critical information from the public. They say that many more Han were killed on July 5 than the government announced.

Chinese President Hu Jintao cut short a trip to Italy, where he was to participate in the Group of Eight summit and hold talks with U.S. President Barack Obama. Having to leave like that was seen as an embarrassment and personal blow to quest for a “harmonious society.” Beijing ‘s Vice Foreign Minister called the riots “a grave and violent criminal incident plotted and organized by the outside forces of terrorism, separatism and extremism.”

Willy Lam wrote in China Brief, “The CCP authorities appear determined to deal a body blow to the so-called three evil forces of separatism, terrorism and extremism...That Beijing means business this time is evident from harsh remarks made in Xinjiang by the Politburo Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang, who is in charge of law and order nationwide. Zhou characterized the crusade against the three forces as a severe political struggle related to upholding national unity, maintaining the interests of the masses, and consolidating the CCP’s ruling-party status. XAR Governor Nur Bekri, the highest-ranked Uighur official in China, added: The [battle] between separatists and counter-separatists is a merciless life-and-death struggle. “[Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, July 23 2009]

“While brandishing the proverbial big stick, the authorities are boosting economic and other aid to the restive region. The central government has played up its own role in developing the XAR?and indicated that more investments and preferential policies are in the pipeline.

“Given the immense resources that are available to the central party-and-state apparatus, few doubt the ability of the Hu Jintao administration to impose ironclad control over Xinjiang through the sheer presence of troops and security personnel.” However “the tenuous inter-racial fabric that has enabled the two ethnic groups to coexist?albeit under stressful conditions?for more than five decades is close to being undone. Should the leadership under President Hu and his underlings in the XAR continue to opt for the iron fist, the majority of Uighurs?who favor non-violent means to attain a higher degree of autonomy, not independence?might be turned into implacable foes of what they will see as chauvinistic Han-Chinese colonizers.”

After the Xinjiang Riots in 2009

After the Urumqi riots thousands fled Urumqi. These included both Uighurs, fleeing to their villages in the Xinjiang countryside, and Han who returned to their home provinces. So many people wanted to get to get out that scalpers were able to sell tickets for five times their face value for trains and buses. One 23-year-old Han construction worker told AFP, It s just too risky to stay here.

Urumqi residents said the demonstrations destroyed businesses and scared visitors away from the city. A week or so after the violence a Hui Muslim vendor told Reuter, It s too tense right here. How can I make money with no customers around? One Uighur woman who did open her shop said We are getting used to [the tension] already.

The curfew that was put in place lasted until early September. Phones, text messaging and Internet service were cut off. A most wanted list of Uighur fugitives with 15 names and photographs was released along with a notice that those who informed or turned themselves in would have their punishments reduced. A Xinjiang Communist official said, We will continue to resolutely crackdown on aggressive move by the enemies and curb violent crimes with an iron hand. Nationwide efforts were stepped to train official how to handle public disturbances.

Willy Lam wrote in China Brief, The strength of the People s Armed Police (PAP) a sister unit of the People s Liberation Army (PLA) that is responsible for upholding domestic stability and ordinary police in the XAR has been bolstered considerably. Soon after his return to China on July 9, Hu, authorized an unprecedented airlift of PAP and allied security personnel to the strife-torn region. For about a week, civilian aviation traffic in cities including Shanghai and Guangzhou was disrupted due to the large number of chartered flights taking PAP officers to the XA. Estimates of PAP and police reinforcements have run into more than 50,000. Beijing authorities have admitted that 31 special public-security squads had newly arrived in Xinjiang to render support to the work of safeguarding stability. [Willy Lam, China Brief]

Reports in the Hong Kong media say crack PAP squads are swooping down on underground groups, particularly in thinly populated towns and villages in western and southern Xinjiang.... This crack down was initiated in the wake of statements by Beijing authorities that unnamed quasi-terrorist Uighur units from southern and western Xinjiang had infiltrated Urumqi shortly before the July 5 melee. Long-time Uighur residents in Urumqi have also complained that police are indiscriminately locking up young men in the XAR capital. Activist Han Chinese lawyers who had provided free legal advice to ethnic-minority communities have been put under 24-hour police surveillance and warned not to take up their cases. Police and state-security personnel are also picking up alleged sympathizers of Xinjiang separatism all over the country.

Internet and Media Crackdown After the Xinjiang Riots

“Immediately after the riots started local Internet service was largely disabled, and online bulletin boards and search engines across China were purged of references to the violence. The social networking service Twitter was also disabled. China Mobile, the nation’s largest cellphone provider, curtailed service in Urumqi, and cellphone calls from some Beijing numbers to the area were blocked. But Chinese television carried images showing some of the violence.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, July 6, 2009]

The governor of Xinjiang defended the decision to shut down the internet and block text messaging, saying the restrictions were needed to prevent further unrest. “In contrast to last year’s unrest in Tibet, where accounts of police and military violence against demonstrators were common, China’s central government moved swiftly to take command of the public depiction of the Urumqi protests and to cripple protesters’ ability to communicate.”

As a result of the official media’s largely emotive if not biased portrayal of indiscriminate Uighur violence against Han Chinese, however, popular Internet chatrooms have been choc-a-bloc with hate messages about the imperative of punishing the ungrateful and unpatriotic Uighurs. [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, July 23 2009]

China Rounds up Hundreds of Uighurs After Xinjiang Riots

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times, Two boys were seized while kneading dough at a sidewalk bakery. The livery driver went out to get a drink of water and did not come home. Tuer Shunjal, a vegetable vendor, was bundled off with four of his neighbors when he made the mistake of peering out from a hallway bathroom during a police sweep of his building. They threw a shirt over his head and led him away without saying a word, said his wife, Resuangul. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 17, 2009]

In the two weeks since ethnic riots tore through Urumqi...security forces have been combing the city and detaining hundreds of people, many of them Uighur men whom the authorities blame for much of the slaughter. The Chinese government has promised harsh punishment for those who had a hand in the violence. To those who have committed crimes with cruel means, we will execute them, Li Zhi, the top Communist Party official in Urumqi.

The vow, broadcast repeatedly, has struck fear into Xiangyang Po, a grimy quarter of the city dominated by Uighurs.... It was here on the streets of Xiangyang Po, amid the densely packed tenements and stalls selling thick noodles and lamb kebabs, that many Han were killed. As young Uighur men marauded through the streets, residents huddled inside their homes or shops, they said; others claim they gave refuge to Han neighbors.

But to security officials, the neighborhood has long been a haven for those bent on violently cleaving Xinjiang, a northwest region, from China. Last year, during a raid on an apartment, the authorities fatally shot two men they said were part of a terrorist group making homemade explosives. Last Monday, police officers killed two men and wounded a third, the authorities said, after the men tried to attack officers on patrol.. This is not a safe place, said Mao Daqing, the local police chief. Local residents disagree, saying the neighborhood is made up of poor but law-abiding people, most of them farmers who came to Urumqi seeking a slice of the city s prosperity.

Residents of Xiangyang Po say police officers made two morning sweeps through the neighborhood after the rioting began, randomly grabbing men and boys as young as 16. That spurred a crowd of anguished women to march to the center of Urumqi to demand the men s release. Nurmen Met, 54, said his two sons, 19 and 21, were nabbed as riot officers entered the public bathhouse his family owns. They weren t even outside on the day of the troubles, he said, holding up photos of his sons. They are good, honest boys.

The detainees did not come home, the residents said, and the authorities refused to provide information about their whereabouts. I go to the police station every day, but they just tell me to be patient and wait, Patiguli Palachi told the New York Times. Her husband, an electronics repairman, was taken in his pajamas with four other occupants of their courtyard house. Palachi said they might have been detained because a Han man was killed outside their building, but she insisted that her husband was not involved. We were hiding inside at the time, terrified like everyone else, she said.

Needle Attacks After the Xinjiang Riots in 2009

In September 2009, a couple months after the riots, reports of syringe attacks in Urumqi panicked the city. Some schools were closed More than 500 people mostly Han Chinese complained of being pricked with hypodermic needles but only 171 showed any evidence of possibly being attacked and maybe less than a dozen really were attacked. Some just had mosquito bites.

The victims were mostly Han and the attackers Uighur, according to the reports. Reports of the attacks sent tens of thousands of Han protesters into the streets; they rallied in front of government buildings and called for a greater clampdown on the Uighurs. [Source: Edward Wong and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, September 12, 2009]

There were rumors that the injections contained toxic chemicals or strains of a deadly infectious disease such as AIDS. The government blamed the attacks on Muslim separatists. Han Chinese in Urumqi blamed the Uighurs. One Han man told Reuters, We thought we could get AIDS or something and kids and women were stabbed so it was really terrifying.

There have been past episodes of mass hysteria related to rumors of syringe attacks in various parts of China, including Urumqi. In some of those instances, official news organizations reported on the attacks, only to have the stories proved false later. In most cases, the attackers were said to be angry people infected with H.I.V., the virus that causes AIDS. None of the recent attacks in Xinjiang involved the transmission of viruses, Xinhua reported.

Li Zhi, Urumqi s Communist Party boss said the syringe stabbings were part of coordinated effort by Muslim separatist to stir up ethnic divisions, This was a grave terrorist crime, he said. The hope; was to create ethnic divisions and stir up ethnic antagonism in a bid to overturn social order, split the motherland and split the Chinese nation.

Response to the Needle Attacks After the Xinjiang Riots in 2009

The attacks and rumors of attacks fueled further resentment by Han towards Uighurs. An Uighur merchant told Reuters, I believe there were some needle attacks by terrorists. But it has really hurt the rest of us, who are completely innocent...Han are the majority here and there aren t very many of us to begin with, and when you walk down the street the Han look at us with such hatred and suspicion. They might beat us up. For the last few days I didn t dare leave my home.

Those caught committing needle attacks face three years to life in prison. Punishment were also harsh for spreading rumors and falsely reporting a needle attacks. According to an official notice: Those who deliberately concoct and spread false information about innocent members of the public being stabbed with needles could be tried and sentenced to up to five years in jail.

The frenzy died down somewhat after military doctors tried to reassure people that the needle attacks would not spread AIDS. One man told Reuters, Now, we know that even if you are stabbed, it s not a big deal, so that s a relief. The main thing is that people are not really hurt.

Twenty-five Uighurs were arrested in connection with the needle attacks. Among them were heroin addicts that used the threat of needle stabbing to rob a taxi driver of around $100 and fight off police trying to arrests them The two involved in the taxi robbery a 34-year-old Uighur man and 22-year-old Uighur woman received sentenced of 10 years and 7 years respectively. Xinhua reported the harshest sentence of 15 years was given to 19-year-old Uighur, Yilipan Yilihamu, for spreading false dangerous substances when he inserted a needle into a woman s buttock on August 28. Four others Uighur men were given sentences between 8 and 15 years for planning a needle attacks against a Han woman in an underground passageway

Trials After the Riots in Xinjiang

More than 2,000 people were detained and 83 were formally arrested. Before he was fired Li Zhi, said to those who have committed crimes with cruel means, we will execute them. Meng Jianzhu, China s top security minister, promised the utmost severe punishment for those who led the violence.

The China Daily article said that more than 200 suspects had been formally charged with an array of crimes related to the rioting. It also said the local police had gathered 3,318 pieces of evidence, including bricks and clubs stained with blood]

James Seymour, a senior research fellow at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. told the New York Times, Justice is pretty rough in Xinjiang. Trials are often cursory. Rights advocates said that the trials in Xinjiang resembled those that took place in Tibet, with many defendants receiving long sentences. There is a lot of concern that those who have been detained in Xinjiang will not get a fair trial, said Wang Songlian, a research coordinator at Chinese Human Rights Defenders, an advocacy group. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 17, 2009]

In a sign of the sensitivities surrounding the unrest, the Bureau for Legal Affairs in Beijing has warned lawyers to stay away from cases in Xinjiang, suggesting that those who assist anyone accused of rioting pose a threat to national unity. Officials on Friday shut down the Open Constitution Initiative, a consortium of volunteer lawyers who have taken on cases that challenge the government and other powerful interests. Separately, the bureau canceled the licenses of 53 lawyers, some of whom had offered to help Tibetans accused of rioting last year in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, July 17, 2009]

Jail Sentences and Executions After the Xinjiang Riots

In October 2009, 21 people were convicted for their roles in the riots for the crimes of murder, intentional damage to property, arson and robbery. Nine were sentenced to death, three given death penalty with two-year reprieve (a life sentence) and the rest were given various prison sentences. Eight of the nine were Uighurs, one was Han Chinese. Their named appeared to to identify them as Uighurs. One of the those given the death penalty, Abdukerim Abduwayit was charged with killing five people with a dagger and metal pipe. Four others wertr charged with beating four people to death and setting ablaze vehicles and shops that killed five others.

The Han man — Han Junbo was given a death sentence for beating an Uighur man to death. Another Han was give a 10-year prison term. One of the Uighurs sentenced to death was found guilty of beating two people to death, with another defendant, and stealing people s cell phones and bracelets. By the time the death sentences were announced a few weeks after the trial, the nine had already been executed.

Also in October 2009, a court sentenced one man with a Han Chinese name to death on charges of intentionally harming others. Another was given life imprisonment and nine others were given prison terms of five to eight years.

More than two dozen Uighurs were executed for other crimes allegedly committed during the riots. In November 2009, nine Uighurs were executed for murder and other riot-related crimes. In December 2009, five Uighurs more were sentenced to death. In January 2010, four more Uighurs were sentenced to death for extremely serious crimes committed during the riots. The determination that the were Uighurs was based on their names.

In October 2009, China sentenced one man to death and another to life in prison on for their roles in a deadly toy factory brawl that was blamed for setting off riots in Xinjiang. Two courts in southern Guangdong Province, where the toy factory was located, also sentenced nine other people to prison terms ranging from five to eight years for taking part in the fights, according to Xinhua. Xiao Jianhua was sentenced to death as the principal instigator in a factory melee. The court said Saturday that Xiao and his accomplices beat the Uighur men with iron bars and obstructed medical workers from treating the injured. [Barboza, Op. Cit]

In January 2011, a 19-year-old Uighur woman was handed a suspended death sentence (usually meaning life in prison) for her involvement in the 2009 riots. She was the second woman to receive such a sentence in connection with the unrest.

In December 2010, seven Uighurs that had sought refuge in Laos after fleeing the riots in Xinjiang were deported to China.

Image Sources: San Francisco Sentinal, AP, AFP, Reuters, BBC

Text Sources: CNTO, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2010