SEZs AND DENG'S ECONOMIC REFORMS IN THE COASTAL AREAS

Congestion outside

the Shanghai port

In the mid-1980s, the "coastal strategy" was emphasized. Agricultural reforms that had begun earlier were extended to the industrial sector and manufacturing centers, modeled after those in Taiwan and South Korea, were established in coastal areas of China. According to the Columbia Encyclopedia: “From 1977, Deng worked toward his two main objectives, to modernize and strengthen the economy and to forge closer political ties with Western nations. To this end, four coastal cities were named (1979) special economic zones (SEZs) in order to draw foreign investment, trade, and technology. Fourteen more cities were similarly designated in 1984. China also decollectivized its cooperative farms, which led to a dramatic increase in agricultural production. In order to control population growth, the government instituted a law limiting families to one child. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

SEZs were set up in the late 1970s near Hong Kong in Shenzhen, near Macau in Zhuhau and across from Taiwan in Xiamen and Shantou. They grew in the 1980s. Industry was reformed by modernizing management, encouraging private business, implementing price reforms, and encouraging foreign investment and trade. China also began welcomed foreign investment and money began flowing in, much of it initially from overseas Chinese investors. Beijing also began streamlining the economy by "squeezing spendthrift state-run companies, overhauling trade, simplifying taxes, canceling preferential policies and reforming banks."

The Deng's reforms were not a complete success. In 1995, grain rationing had returned to 29 cities, price caps were placed on sugar and cotton because of problems in the agricultural sector. Economic reforms in the industrial sector created sweat shops and a society of haves and have-nots.

Good Websites and Sources on Deng Xiaoping: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; CNN Profile cnn.com ; New York Times Obituary; China Daily Profile chinadaily.com. ; Wikipedia article on Economic Reforms in China Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Special Economic Zones Wikipedia ;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: AFTER MAO factsanddetails.com; AFTER MAO: THE RISE OF DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING factsanddetails.com; DENG XIAOPING'S EARLY ECONOMIC REFORMS factsanddetails.com; ECONOMIC HISTORY AFTER DENG XIAOPING Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Deng Xiaoping “Deng Xiaoping and China's Economic Miracle” by Rene Schreiber Amazon.com; “China Under Deng Xiaoping: Political and Economic Reform” by John; David Watkin & G.Tilman Mellinghoff Summerson, illustrated Amazon.com; “Idealogy and Economic Reform Under Deng Xiaoping 1978-1993" by Wei-Wei Zhang Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China" by Ezra F. Vogel (Belknap/Harvard University, 2011) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life” by Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: My Father" by Deng Maomao (1995, Basic Books) Amazon.com; “Deng Xiaoping's Long War: The Military Conflict between China and Vietnam, 1979-1991" by Xiaoming Zhang Amazon.com; “The Deng Xiaoping Era: An Inquiry into the Fate of Chinese Socialism, 1978-1994" by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; "Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping" by Richard Baum (1996, Princeton University Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Chinese Revolution: A Political Biography" by David S.G. Goodman (1994, Routledge) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Chronicle of an Empire" by Ruan Ming (1994, Westview Press) Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping and the Making of Modern China" by Richard Evans 1993 Amazon.com; "Deng Xiaoping: Portrait of a Chinese Statesman" edited by David Shambaugh (1995, Clarendon Paperbacks) Amazon.com; "The New Emperors: Mao and Deng — a Dual Biography" by Harrison E. Salisbury (1992, HarperCollins) Amazon.com After Mao “China After Mao: The Rise of a Superpower” by Frank Dikötter, Daniel York Loh, et al. Amazon.com; “Mao's China and After: A History of the People's Republic” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; “The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao” by Ian Johnson Amazon.com; The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966-1982" by Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank Amazon.com; "The Penguin History of Modern China" by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com; “The Search for Modern China” by Jonathan D. Spence Amazon.com

Changes After the Deng's Market Reforms

Although the momentum and push for economic reforms came from Deng. Many of the concrete changes have been the result of small, incremental bureaucratic adjustments that loosened the draconian controls that existed in the Mao era. Among these was the introduction of national identity cards in the 1980s that allowed people to travel and find work easier. Before that travelers needed a letter from local officials. Later the system of food coupons which could only used in local markets was abolished and gradually the household registration system was eased.

As the Deng reform picked up speed there was a marked switch from dogmatist socialism towards a large undefined mix of authoritarianism, corruption and capitalism described by some as "market Leninism." In the 1980s managers gained freedom from central, but not local authorities. Small worker-owned firms proliferated as did corrupt officials. Before long 80 percent of industrial enterprises employed less than 75 people and consumers enjoyed unprecedented choice.

The state continued to control the prices of raw materials and grains and set acceptable price ranges for consumer goods and services. Businesses had to beware. At any time they could be shut down by the government for engaging in unfair trading practices. Whether they really were or not didn’t really matter. What matter was sucking up to the right individuals and agencies.

China’s opened it first stock exchange in Shanghai in 1990. In 1996 Chinese currency became convertible. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, fledgling entrepreneurs were invited to join the Communist party. Businesses and factories were required to have a Communist party cell and businesses and politics became intertwined.

China's Aims to Get Rich

Audi sports car

In the 1980s Deng Xiaoping said, "To get rich is glorious" and later added "some should be allowed to get rich first." Many Chinese have taken this maxim to heart and have become very rich.

Dutch journalist Willen van Kemendade wrote in his book "China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Inc", that the Chinese people had evolved from being "Mao-worshiping blue ants" to "nihilistic, ultra-individualistic, money-worshiping hedonists."

Fueling the drive to get rich has been cheap labor often working under horrid conditions. “China,” wrote Sheryl Wudunn in the New York Times magazine in the mid 1990s, "is something of a cross between Dodge City and Dickensonian England. It's a lawless place motivated by a strange mix of greed and apprehension that this wonderful money-making opportunity could end at any moment. China may not use little boys as chimney sweeps, but the textile and garment industries work children 14 hours a day, seven days a week, and often they sleep by their looms. If you lose your arm in the loom, you're fired. That may sound grim, but 19th-century capitalism is a big improvement over 18th-century feudalism.

SEZs in Shenzhen and the Pearl River Delta

The first special economic zone (SEZ) was established in Shenzhen in 1980. Wary of a rival power bases in economically powerful Shanghai, Deng chose the extreme south to launch his reforms and economic experiments.

The heart of Deng's economic reforms was the establishment of Special Economic Zones (SEZs) along China's southern coastline. Here Chinese businesses and foreign investors were lured with chances to make huge profits and incentives such as low taxes, cheap land, cheap labor and comparative economic freedom.

The most productive SEZs’shenzhen and other places in the Pearl River Delta — are located near Hong Kong and Guangzhou (Canton). Shenzhen has posted economic growth of an astounding 45 percent a year, and population growth of 20 percent a year. It has been so successful that for a while it was protected by an electric fence intended to keep mobs of Chinese opportunity seekers out. See Shenzhen

Worried that the Special Economic Zone will be overrun with job seekers, the government has barred people from entering Shenzhen that don't have government-issued permits which are usually only given to people with needed skills and connections. Factories outside of Shenzhen in places like Dongguan have accepted workers without government permits.

The SEZs emerged around the same time that Hong Kong and Taiwan were moving from light manufacturing into more high tech manufacturing and businessmen were looking for new place to do their sweat shop labor. The SEZs in China were less than a hour away, with China providing a bottomless pit of cheap labor.

The Chinese government modernized the infrastructure, attracted Chinese entrepreneurs with tax exemptions for doing business with foreign companies, and lured foreign investors with tax holidays and a large bonded zone for duty-free imports of raw materials. By 1989 nearly 22,000 joint ventures had been launched, 952 with American firms. Chrysler and Coca-Cola were among the first American firms to launch joint ventures.

Relatively litle paper work was needed to get a business started. One businessman in Shenzhen told National Geographic, "If we had chosen Beijing as our site we would have spent years obtaining the necessary bureaucratic approvals. The people her got the factory ready for us in one year."

See Shenzhen, Pearl River Delta, Places; Regional Economics, Economics

Deng’s Southern Tour

The pace of economic reforms stalled after the June 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. The United States responded to the vent by imposing trade sanctions as did other countries. Trade and economic growth slowed. Momentum for the China’s economic reforms accelerated in 1992, when Deng, fed up with three years of stalled economic reforms and a lack of imagination and will among the party faithful, took his famous ‘southern Tour.” He traveled to Shenzhen—then a boomtown—and coined the term ‘socialist market economy,” in the process giving a ringing endorsement to privatization and free enterprise and encouraging foreign investors to bring their money to China.

In 1992 Deng made his southern China try to relaunch economic reforms in the face of criticism from conservatives. The tour was primarily a political gambit to address the rising power and obstacles created by hard liners in the party that used Tiananmen Square as an illustration as what reforms have brought. John Delury, associate director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations, wrote: After the massacre “Deng temporarily withdrew, letting the central planner around the party elder Chen Yun slow down marketization and weather China’s international isolation in Tiananmen’s wake.”

Deng re-emerged into public life in dramatic fashion with his southern tour. In Shenzhen, with television cameras rolling, he raised his finger in the air and said, “If China does not practice socialism, does not carry on with “reform and opening” and economic development, does not improve the people’s standard of living, then no matter what direction we go, it will be a dead end.” With this gesture Deng reaffirmed his support for reforms that started in 1979 and had been stalled by Tiananmen square and purged or at least diminished the power of the hardliners.

Legacy of Deng’s Southern Tour

According to “Countries of the World and Their Leaders”: Deng Xiaoping's dramatic visit to southern China in early 1992. Deng's renewed push for a market-oriented economy received official sanction at the 14th Party Congress later in the year as a number of younger, reform-minded leaders began their rise to top positions. Deng and his supporters argued that managing the economy in a way that increased living standards should be China's primary policy objective, even if “capitalist” measures were adopted. Subsequent to the visit, the Communist Party Politburo publicly issued an endorsement of Deng's policies of economic openness. Though not completely eschewing political reform, China has consistently placed overwhelming priority on the opening of its economy. [Source: Countries of the World and Their Leaders Yearbook 2009, Gale, 2008]

Delury wrote that in the tour “Deng orchestrated the eclipse of the anti-market conservatives faction. ...Having begrudgingly purged the reformers in 1989...Deng in 1992 seized the opportunity to sideline the central planers, and bring China’s neo-liberal hero, Zhu Rongji, to refire the engines of the economy. Deng judged the mood of the nation shrewdly: the people were ready to be told that: “to get rich is glorious.” The new party leadership of the 1990s and 2000s did not waver from Deng’s line: steady expansion of market reforms, active involvement in international commerce, massive urbanization and urban development, and total dedication to to party unity.”

In doing this Deng is credited with saving the Chinese Party by providing a valve for discontent. Economic prosperity has sustained internal political stability and given people something other than politics to think about.

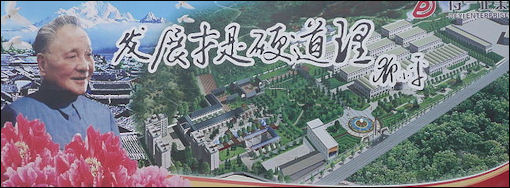

Deng billboard

Achievements of the Deng Reforms

Some have called the “reform and opening” policy the greatest poverty-reducing program in history. It not only launched a period of economic prosperity in China it lifted 200 million people out of poverty. At the time the “reform and opening” policy was approved China was still suffering from famines and the per capital GDP of China was 381 yuan. In 2007 it reached 18,900 yuan ($2,760).

In the late 1980s people still largely wore gray Mao jackets and rode bicycles. Finding a jar of instant coffee was difficult. A single plastic bag was considered a luxury. Lights were generally out by 9:00pm even in Beijing and Shanghai,

It has been said the party’s polices lifted hundreds of million out of poverty but it can also be argued that the policies simply freed them and the people that lifted themselves out of poverty through their hard work and long hours.

GDP growth in the PRC has averaged more than 9 percent since 1989 and reached as high as 14.2 percent in 1992 and 2007, according to the World Bank. Savings increased 14,000 percent and exports went from $10 billion a year to almost $1 trillion between the 1980s and 2000s. An estimated 400 million people have been lifted out of poverty; perhaps 100 million people have been booted up the middle class; and China rose from an economic backwater into the world's third largest economy.

Michael Anti, the columnist and blogger, said the breakdown of old restrictions meant that “you could break all of your contracts, your promises. You could do whatever you wanted.” Jack Ma, lead founder of the Alibaba Group, said, “The change, to me, is that people were not ashamed to be businesspeople.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker]

See Deng Reforms and the Poor, Poor, Life

Emergence of Shanghai as an Economic Center

Places in southern China near Hong Kong and Guangzhou were selected as the over Shanghai — the traditionally center of Chinese commerce” in part because Beijing was worried it would not be able to keep control over Shanghai’s notoriously capitalist-minded people.

Shanghai was not opened up economically until 1991, after Tiananmen Square, when Beijing wanted to appease popular discontent by distracting them with the potential to make money. Once cut loose the Shanghaiese quickly made up for lost time. To attract foreign investment it offered cheap office space, tax breaks and promised minimal red tape. Foreigners came in droves. Within 15 years Shanghai surpassed Shenzhen and Pearl River Delta as China’s primary industrial zone

A number of new SEZs and SEZ-like areas were opened up near Shanghai, particularly in Zhejian Province. Lishui Economic Development Zone is one of the newest of these. Situated in the mountains of Zhejian Province, far from anything, it is connected to the outside world by a new highway and has among the cheapest land rates and labor costs on China.

Lishui’s population grew from 160,000 in 2000 to 250,000 in 2006. The local government invested $8.8 billion in infrastructure. A factory zone was created by relocated thousands of people and chopping of the tops of 108 separate mountains and hills, using dynamite. bulldozers, excavators and dump trucks to knock down the highest areas and fill in the lowest areas. Thousands of companies set up shop there.

Pudong in Shanghai

Phenomenal Growth in China

China has the fastest growing economy in the world for many years now, an astounding fact when you consider how large the country is. It has managed to maintain a 10 percent growth rate through the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s and did not suffer to much from the Asian Economic Crisis in the late 1990s and a global slump in the early 2000s.

Growth has averaged over 10 percent for the last 30 years. It was 9.4 percent between 1978 and 1995. It was 11.2 percent between 1990 and 1998 and 11.2 percent between 1990 and 1998 and just under 10 percent between 1999 and 2007.

China’s growth rate has been five and six times higher than the growth rate in the United States, Japan and the major countries in Europe. The only countries that have posted similar growths rates over extended periods of time in recent years have been Japan in the 1960s, 70 and 80s and South Korea in the 1970s, 80s and 90s. If the Chinese economy continues growing a rate of 9 percent it will double every ten years.

Between 1980 and 2000 China relied mainly on light industry to generate growth. Some economists also claim much of the growth has been artificial, stimulated by heavy government spending, subsidies, cheap electricity and bank loans that will never be repaid (See Banks). The environmental costs of the rapid expansion have been huge: foul air, water shortages. With its low wages and prices China exported deflation abroad.

Along with the economic growth came high prices. In Chinese cities. the prices of office space and housing have soared. Very quickly Shanghai went from being one of the world’s cheapest cities to one of the most expensive, with Western-style, two-bedroom apartment going for $8,000 a month or more. Along with affluence come an increase in crime and corruption, with some of the biggest windfalls hauled in by by government and military officials and "princelings" — the children of officials.

Regions in China Left Out of the Economic Boom

Development and growth has been spotty and uneven. While Beijing and Shanghai have been ranked by the United Nations as equivalent to Greece and Singapore on a per capita GDP level the provinces of Gansu and Guizhou have been ranked with Haiti and Sudan.

The economic boom has mainly benefitted the 300 million or so urban Chinese living in and around the coast. The 18 central and western provinces have mainly been left out of the economic miracle and the majority of China's 900 million rural residents still live in feudal conditions as subsistence farmers.

Some places like Heliongjong and the northeast in general — the home of China’s oil and heavy machinery industry — prospered in Maoist era have declined since the Deng reforms kicked in. The oil and heavy machinery industry there have declined; places like Harbin have an unemployment rate double those in the the rest of country; governments have been unable to attract much new industry; and some of the jobs that remain pay only $12 a month. The people who seem most well off in Harbon are the official that live in what has been dubbed Corruption Street.

One Chinese scholar told the New York Times, "Every country has regional differences, but in China the regional differences are getting bigger, not smaller." the situation is getting so serious that government has to drop tax breaks for companies doing in the coastal provinces out feat that crime, insurgency and warlordism will rise in the central and western provinces as a result of the disparities.

Closer Look at Deng’s Economic Policies

Fang Lizhi wrote in the New York Review of Books, “On a per capita basis, China’s GDP is still only a quarter of Taiwan’s, a fifth of South Korea’s, and a tenth of Japan’s. Moreover the engine of China’s growth remains, for the most part, low-end products produced by cheap labor, where China has a competitive advantage. In history China has had this kind of ‘superiority” before. In 1820, under the Qing dynasty, the GDP of China’s largely agricultural economy was six times that of industrialized England. But England had gunboats, and when the Opium Wars came, it had its way with China. [Source: Fang Lizhi, New York Review of Books, November 10, 2011, in a review of "Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China " by Ezra F. Vogel]

statue of Deng in the Shenzhen Museum

The Chinese government likes to claim that it has lifted millions from poverty as part of the greatest program to improve the condition of the poor the world has ever seen. Westerners sometimes echo such claims. Vogel tells us that “today hundreds of millions of Chinese are living far more comfortable lives than they were living in 1989" thanks to “the most basic changes since the Chinese empire took shape during the Han dynasty over two millennia ago.” In such claims, terms like “poverty” and “famine” are never defined with enough rigor to allow much quantitative measurement through history, and people unfamiliar with Chinese history can be led to suppose that China for two thousand years resembled something like Somalia today.

But this is hardly the case. Chinese history does contain many records of poverty and famine, but, insofar as these events can be quantified, it is hard to say that their extent, on average, exceeds what occurred in other parts of the world. The suggestion that two thousand years of Chinese history were mired in chronic poverty is inconsistent with what we know about the rise and fall in the size of the population. Wars and invasions often caused the population to decline, but in times of peace the consistent pattern was that population grew rapidly. The huge Mao-made famine of 1959–1962 (which killed thirty or forty million people) showed us that, in times of famine, pregnancy rates fall drastically and population growth slows, even to zero. Peacetime population growth, the standard pattern in China’s long history, is a clear sign of absence of poverty. To say that Deng is responsible for the largest program to eliminate poverty and famine in world history is political hype.

Moreover, the claim that Deng “lifted” millions from poverty confuses the doer and the receiver of action. To the extent that economic “lifting” has happened in post-Mao times, it has been the menial labor of hundreds of millions of people — working without labor unions, or a free press, or a neutral judiciary, or protections like OSHA rules — that has done the heavy lifting. This workforce has improved not just the lives of the millions themselves but, even more, of the Communist elite, who in many cases have soared to stratospheric heights of opulence. World Bank figures show that in China the Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality in populations, has skyrocketed from 0.16 before Deng’s reforms to a current 0.47, near the high end of the scale. This dramatic change has much less to say about “hundreds of millions” than it does about one of the maxims that Deng delivered at the outset of reform: “Let a part of the population get rich first.”

Deng never specified which “part” he had in mind. He left this for Chinese people themselves to figure out. For me personally, the realization arrived most clearly with a surprising series of events that happened to me in the late 1980s.

Western observers have found it incongruous that Deng was so active in pushing economic reform but so stubborn in preventing political reform — as if these were in some way contradictory policies. But there was no contradiction: one policy was aimed to bring wealth to the Party-connected elite and the other was aimed to preserve its power. To use the Party’s army to suppress student protesters who threatened Party wealth and power was entirely consistent with his basic principles.

Legacy of Deng’s Economic Reforms

On an exhibition in Beijing in 2018, ostensibly marking the anniversary of Deng’s economic reforms, Amanda Lee wrote in the South China Morning Post: “State-owned enterprises are much more prominent than the private sector and President Xi Jinping far more visible than Deng Xiaoping in a special exhibition marking 40 years since China’s reform and opening up, stressing the Communist Party’s role in the economy even as Xi courts private firms to help stabilise growth during the trade war with the United States. [Source: Amanda Lee, South China Morning Post (November 16, 2018]

Deng Xiaoping, who began reforms that transformed the economy, is marginalised in displays. The exhibition, at the National Museum of China in Beijing, devotes half of a display about Chinese leaders to the achievements of Xi, who took office in 2012 yet receives more emphasis than former paramount leader Deng – under whom China began its economic transformation in 1978 – and his successors. Zhu Rongji, the former premier who engineered China joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001, is nowhere to be seen. “Shanghai-based political analyst Chen Daoyin said the show’s focus on the present leadership was intended to deliver a strong message that China had entered a new era, signalling an end to the “old China” led by Deng’s ideas. In 2017, the 19th National Congress declared that China has entered a new era – that is, the era of Xi,” said Chen. “As such, the symbolic significance of the exhibition is that Deng Xiaoping’s era has come to an end, and China is moving forward and has entered a new world: the era of Xi.” That the exhibition deifies the current leadership and diminishes the impact of former reformers such as Deng is also an attempt to revise history, said Zhang Lifan, a prominent scholar of modern Chinese history in Beijing.

“The economic contribution of the private sector – which accounted for nearly two-thirds of the country’s growth and nearly 90 per cent of its new urban jobs in 2017 – was acknowledged at the show, but the number of displays about private firms was dwarfed by that for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). E-commerce giant Alibaba, internet titan Tencent, search leader Baidu, smartphone manufacturer Xiaomi, laptop maker Lenovo and carmaker Geely are among the private firms to feature in the show. But it is China’s scientific and technological achievements in areas dominated by state firms that are the most visible. Displays on aerospace, submarines, aviation, biology, medicine, physics, semiconductors and robotics are scattered through the exhibition.

“This is in line with Beijing’s controversial “Made in China 2025” industrial plan, although the plan itself isn’t mentioned in the exhibition. Unveiled in 2015, the plan is aimed at developing the country’s cutting-edge industries – such as robotics, aerospace and new energy vehicles – so that it can replace imports with locally made products and take on Western tech giants. Meanwhile, the trillion-dollar “Belt and Road Initiative”, the state-backed push for global influence by funding and building infrastructure projects, is depicted in the exhibition as a blueprint for China opening up its markets and defending free trade.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; Deng poster, Landsberger; Market, Nolls China website; buying a TV, Ohio State University

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021