AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER MAO

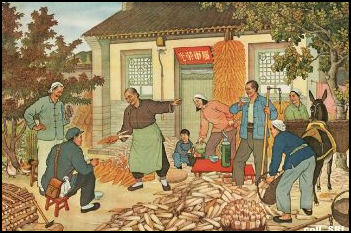

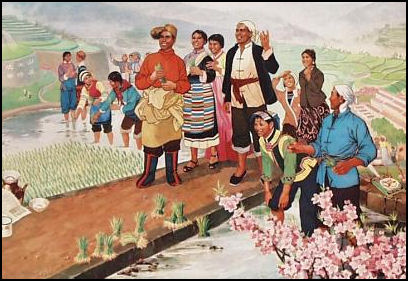

Land reform poster

As is true with all land, farm land is owned by state in China. In the Mao-era most farming was done at collective farms and state farms. Food produced by farms was sold to the state at fixed prices that were generally lower than the prices of the same food sold on the open market. As a result the farms were dependent on government subsidies to remain afloat. Agricultural productivity was low. Farmers lacked incentives to be productive; infrastructure and transportation problems prevented food from getting from the fields to people's homes before it spoiled; poor land management exhausted soils and water supplies. There were also weather problems. The low productivity resulted in shortages and even famines.

To increase productivity, chemical fertilizer plants were built, hybrid-seed programs were developed, insecticides were used, rivers were irrigated. Many of these programs had negative effects on the environment.

During the war to take power, the Communists promised land to the poor. When the Communists came to power they began seizing land from landowners and distributing it among the poor. Each family got no more than 1.3 acres. Land owners that resisted giving up their land, even as little as two thirds of an acre, were often executed.

Before the early 1980s, most of the agricultural sector was organized according to the three-tier commune system. There were over 50,000 people's communes, most containing around 30,000 members. Each commune was made up of about sixteen production brigades, and each production brigade was composed of around seven production teams. The production teams were the basic agricultural collective units. They corresponded to small villages and typically included about 30 households and 100 to 250 members. The communes, brigades, and teams owned all major rural productive assets and provided nearly all administrative, social, and commercial services in the countryside. The largest part of farm family incomes consisted of shares of net team income, distributed to members according to the amount of work each had contributed to the collective effort. Farm families also worked small private plots and were free to sell or consume their products. [Source: Library of Congress]

penetrate the countryside stamp “Four percent of the nation's farmland was cultivated by state farms, which employed 4.9 million people in 1985. State farms were owned and operated by the government much in the same way as an industrial enterprise. Management was the responsibility of a director, and workers were paid set wages, although some elements of the responsibility system were introduced in the mid-1980s. State farms were scattered throughout China, but the largest numbers were located in frontier or remote areas, including Xinjiang-Uygur Autonomous Region in the northwest, Inner Mongolia, Autonomous Region, the three northeastern provinces of Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning and the southeastern provinces of Guangdong, Fujian, and Jiangxi. *

"Mao Zedong's legacy to Chinese agriculture is mixed," scholar Richard Critchfield writes, "He gave agriculture and the peasant top priority in investment, something India has failed to do. Yet the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution, along with forced collectivization, set back scientific research for years and in 1959-61 an estimated 30 million Chinese died of famine. [Source: "The Villagers" by Richard Critchfield, Anchor Books]

Websites: Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Books and Posters Landsberger Communist China Posters ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao ; Mao Quotations art-bin.com; Marxist.org marxists.org ; New York Times topics.nytimes.com; Early 20th Century China : John Fairbank Memorial Chinese History Virtual Library cnd.org/fairbank offers links to sites related to modern Chinese history (Qing, Republic, PRC) and has good pictures;

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; JAPAN IN CHINA: WAR AND OCCUPATION BEFORE AND DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; MAO ZEDONG, HIS EARLY LIFE AND RISE IN THE CHINESE COMMUNIST PARTY factsanddetails.com; MAO ZEDONG’S EARLY IDEAS ABOUT MAOISM AND REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; COMMUNISTS TAKE OVER CHINA factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS ESSAYS BY MAO ZEDONG AND OTHER CHINESE COMMUNISTS AS THEY TAKE POWER factsanddetails.com; EARLY COMMUNIST CHINA UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; MAO'S PERSONALITY CULT, LEADERSHIP AND MAOIST PROPAGANDA factsanddetails.com JIANG QING, LIN BIAO, ZHOU ENLAI factsanddetails.com; DAILY LIFE IN MAOIST CHINA factsanddetails.com; BAREFOOT DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE IN THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com; KARL MARX: HIS LIFE, IDEAS, BOOKS, HEGEL AND MARXISM factsanddetails.com; SOCIALISM, COMMUNISM, CAPITALISM, LENINISM AND MAOISM factsanddetails.com ; RURAL LIFE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; VILLAGES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; ; AGRICULTURE IN CHINA UNDER DENG XIAOPING Factsanddetails.com/China ; RICE AGRICULTURE IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The China Threat: Memories, Myths, and Realities in the 1950s” by Nancy Bernkopf Tucker Ph.D. Amazon.com ; “Building New China, Colonizing Kokonor: Resettlement to Qinghai in the 1950s” by Gregory Rohlf Amazon.com ; “The Gender of Memory: Rural Women and China's Collective Past” Illustrated by Gail Hershatter Amazon.com; “From Rebel to Ruler: One Hundred Years of the Chinese Communist Party” by Tony Saich, Nigel Patterson, et al. Amazon.com; "Mao; the Untold Story" by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Knopf. 2005) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 3" (1938-1941) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 4" (1941-1945) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: The Complete Works Volume 5" ( 1944 and 1948) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 14: The People's Republic, Part 1: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949-1965" by Roderick MacFarquhar and John K. Fairbank Amazon.com "China Witness, Voices from a Silent Generation" by Xinran (Pantheon Books, 2009) is collection of oral histories from Chinese who survived the Mao period Amazon.com . "Fanshen" by William Hinton is the classic account of rural revolution during the communist-led civil war in the late 1940s Amazon.com; “Penguin History of Modern China: 1850-2009” by Jonathan Fenby Amazon.com;; "China: A New History" by John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

Land Reform in China Under Mao

Paper for right to use land

The Communist Party’s greatest legacy arguably has been taking land from wealthy landlords and rich farmers and redistributing it in rural areas among the poorest peasants under the principal of “land of the tiller.” During the war to take power, the Communists promised land to the poor. When the Communists came to power they began seizing land from landowners and distributing it among the poor. Each family got no more than 1.3 acres. Land owners that resisted giving up their land, even as little as two thirds of an acre, were often executed.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: The build-up of heavy industry was pushed the Communist Chinese,, but industrialization had to be paid for, and, as in other countries, it was basically agriculture that had to create the necessary capital. Therefore, in June 1950 a land-reform law was promulgated. By October 1952 it had been implemented at an estimated cost of two million human lives: the landlords. The next step, socialization of the land, began in 1953.The co-operative farms were supposed to achieve higher production than small individual farms. It may be that any farmer, but particularly the Chinese, is emotionally involved in his crop, in contrast to the industrial worker, who often is alienated from the product he makes. Thus the farmer is unwilling to put unlimited energy and time into working on a farm that does not belong to him. But it may also be that the application of principles of industrial operation to agriculture fails because emergencies often occur in farming and are followed by periods of leisure, whereas in industry steady work is possible. [Source:“A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1977, University of California, Berkeley]

After 1949, farmers classified as "poor peasants" by the Communists were given ownership to land taken away from local landlords and rich farmers. Estates and large farms were divided and peasants got small parcels of land. Each family got no more than 1.3 acres. One farmer told the New York Times, "Of course we were extremely happy — everyone was happy we got land!" The seizure of land was not always easy. In some cases “certain necessary steps” had to be taken and this resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of people. In many cases villagers were executed or beaten to death by fellow villagers to get their land. See Violence in the Early Years of the People's Republic Below.

The peasants didn’t hold on to their land for long. By the late 1950s, private land ownership was eliminated and peasants were given usage rights to the land but not ownership. The land from then on was owned by the state. Peasants were organized into teams and then collectives and became property-less members of “people’s communes.” Similar scenarios were played in the cities. Rich families who stayed in Shanghai after Communist Revolution were told they had nothing to worry about, but in the end their land and property was expropriated. The Communists also confiscated their art. One Hong Kong art dealer told the New York Times. "The Shanghai museum's best pieces are all from those private collections."

Top down economic plans after independence bore fruit. The national income rose at rate of 8.9 percent a year between 1953 and 1957 bu created problems down the road. Giving peasants usages rights rather than ownership paved the way for the seizures of land by local officials and businesses that is taking place today.

“Land Wars: The Story of China’s Agrarian Revolution” by Brian DeMare (Stanford University Press, 2019) draws on new archival sources and vivid narrative accounts of rural revolution from Ding Ling, Eileen Chang, and William Hinton. From the back cover: Mao Zedong’s land reform campaigns comprise a critical moment in modern Chinese history, and were crucial to the rise of the CCP. In Land Wars,Brian DeMare draws on new archival research to offer an updated and comprehensive history of this attempt to fundamentally transform the countryside. Across this vast terrain loyal Maoists dispersed, intending to categorize poor farmers into prescribed social classes, and instigate a revolution that would redistribute the land. To achieve socialist utopia, the Communists imposed and performed a harsh script of peasant liberation through fierce class struggle. While many accounts of the campaigns give false credence to this narrative, DeMare argues that the reality was much more complex and brutal than is commonly understood—while many villagers prospered, there were families torn apart and countless deaths. Uniquely weaving narrative and historical accounts, DeMare powerfully highlights the often devastating role of fiction in determining history. This corrective retelling ultimately sheds new light on the contemporary legacy of land reform, a legacy fraught with inequality and resentment, but also hope.

Liu Wencai: The Despotic Pre-Communist Landlord

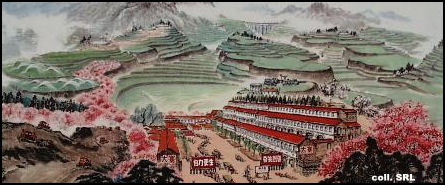

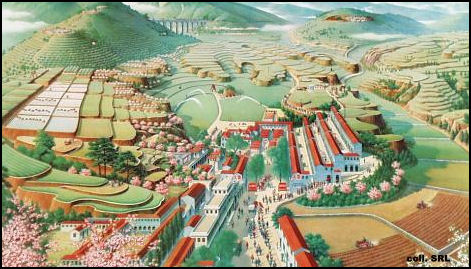

redistributing land

Anren (in Dayi County, 40 kilometers west of Chengdu) was the hometown of Liu Wencai, a Qing dynasty warlord, landowner and millionaire. His 27 historic mansions have been well preserved and turned into museums. Liu's Manor Museum (in Anren) is the former residence of the Liu family and the big landlord Liu Wencai. It covers an area of 70,000 square meters, and consists of two big architecture groups. The buildings are very luxurious, and include various shapes such as rectangles, squares and terraces. It was converted into a museum in October 1958. It now houses an extensive collection of over 27,000 cultural relics, including a suit of rosewood desks and chairs with marbles in it. In addition, 8 of them are embedded with 27 colorful pearls. The manor exhibits the life of Liu Wencai, which consisted of four parts, and shows the day-to-day life of the affluent landlord.

Vanessa Piao wrote in the New York Times’ Sinosphere: “To many Chinese, Liu Wencai is the archetype of the despotic landlord from pre-Communist days, one who exploited his tenants, tortured those who fell behind on rent in a “water dungeon” and forced new mothers to breast-feed him as a longevity therapy. Liu Wencai, born in 1887, amassed huge wealth in the 1920s in the Yangtze River port of Yibin, dominating lucrative businesses including the opium and weapons trades under the wing of his younger brother, Liu Wenhui, a Nationalist warlord. In 1933, Liu Wenhui retreated to the Tibetan region of Kham, after losing a battle to a warlord nephew, and Liu Wencai returned to his hometown, Anren, and sponsored road, water and electricity projects as well as the school.[Source: Vanessa Piao, Sinosphere, New York Times, July 26, 2016]

Liu Wencai died in October 1949, the same month that Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People’s Republic. The Liu family, like many wealthy Chinese, considered fleeing to Hong Kong, fearing what might happen under the new Communist government, Mr. Liu said. But Liu Wenhui urged them to stay, insisting the family would be treated well as the party’s friend. Instead, the family’s property was seized and its members attacked in a series of political campaigns. In 1958, local officials eager to demonstrate their fervor for Maoist class struggle presented Liu Wencai as the prototype of the exploiting landlord. His coffin was dug up, and his remains were scattered.

“In 1959, the landlord’s residence was turned into a museum, featuring a “water dungeon,” an underground space half-filled with water. A woman who claimed to be the dungeon’s sole survivor described it as filled with human bones. By the early 1960s, Liu Wencai was nationally notorious as the “chief representative of the landlord class for 3,000 years.” His brother Liu Wenhui, who in 1959 became forestry minister and escaped persecution under Zhou Enlai’s protection, was powerless to reverse the propaganda campaign, though he was secretly upset. “What the hell are they talking about?” was his private comment on one newspaper article about Liu Wencai, according to his grandson Liu Shizhao.

“In 1965, the Sichuan authorities commissioned more than 100 life-size clay sculptures that the museum installed as the Rent Collection Courtyard, which purported to show how Liu Wencai and his lackeys bullied peasants to extract rents. Replicas of the statues were exhibited in Beijing later that year, drawing hundreds of thousands of visitors. In 1966, just before the onset of the Cultural Revolution, a documentary about Liu Wencai was released, and stories of his crimes were subsequently included in textbooks.

“Denunciations of the landlord and the evil he ostensibly personified surged during the Cultural Revolution. Family members came under attack. A cousin of Mr. Liu who fled to Xinjiang was murdered along with his wife and children, as were many other people in China branded as “landlords.” The frenzy subsided only in the 1980s, when liberal voices were tolerated to some extent. In 1988, the provincial authorities admitted that the water dungeon was an invention, and it was drained. But these beginnings of a re-evaluation stalled after the 1989 Tiananmen crackdown as the party tightened its grip, Mr. Liu said.

Liu Wencai: Not the Despotic Landlord He Is Made Out to Be?

Liu Wencai’s grandson Liu Xiaofei, who was 70 in 2016, has spent a good portion of life decades trying to prove that his grandfather was not only a good man, but actually aided the Communist forces in Sichuan Province. “The ruling party has no integrity, so I have to tell the truth,” Liu told the New York Times. “He said he was not seeking his grandfather’s formal rehabilitation but simply trying to establish that the government fabricated stories to advance its political goals. “By inciting hatred through propaganda, they turned humans into beasts,” he said. “I want to tell the truth so our nation won’t repeat these mistakes.” The exhibits at his family house in Anren are mostly fakes, he says.

Vanessa Piao wrote in the New York Times’ Sinosphere: “Mr. Liu said it was a single sentence his mother uttered in the late 1960s, during the Cultural Revolution, that sent him on his journey, a one-man battle even family members consider doomed in a tightening political climate. ““The underground Communists’ command headquarters was right in our manor,” he said she told him. “Those words were engraved in my heart.” Many residents in Anren seem to remember Liu Wencai favorably. “If you ask if people here think Liu Wencai was good, that goes without saying,” said Dai Rongyao, 89, who was selling embroidered handicrafts.

redistributing land

When Wencai returned to Anren after his time in Tibet he “sponsored road, water and electricity projects as well as the school. In 1942, Liu Wenhui, long at odds with the Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, met with Zhou Enlai and began clandestinely cooperating with his Communists. In 1946, at the start of the Chinese civil war, Liu Wencai financed a Communist guerrilla force of around 50 people while allowing its command headquarters to be set up in his manor, said Mr. Liu, who said he learned this from a close aide to Liu Wencai who has since died. (A provincial government history says that underground Communists took advantage of Liu Wencai’s conflict with a rival to secure weapons from him.) In December 1949, his brother Liu Wenhui openly joined forces with the Communists, and the Nationalists retreated from Sichuan to Taiwan.

“Xiao Shu, the pen name of Chen Min, who in 1999 published “The Truth About Liu Wencai,” a book that was soon banned, said the party would be reluctant to restore to respectability a villain of its own making. His book was accused of “negating the legitimacy of the new democratic revolution,” when the party persecuted landlords and distributed their property to poor peasants, he said. “This is the basis of the regime’s legitimacy, so they don’t dare face the truth.” Wu Hongyuan, 60, a retired county propaganda official who served as the museum’s director in the 1990s, said the process of restoring the truth could not be rushed. “The museum is too sensitive, and Liu Wencai is too famous,” he said.

“Mr. Wu said he tried to recast the museum to more accurately present Liu Wencai’s life, but anytime he altered something, he said, former underground Communists in Anren would protest to the authorities. Li Weijia, 98, was one of those protesters. He never protected party members!” insisted Mr. Li, in a hospital ward reserved for senior officials in Chengdu. “That’s confusing black and white!"...Chen Fahong, 86 is a former worker in Liu Wencai’s manor. “We had rice and meat to eat then. He was kind,” Mr. Chen told the New York Times of Liu Wencai. “After liberation” in 1949, he said, “we had only bran and grass to eat.”

Collectivism in China

In the early 1950s the Communists helped form mutual aid teams, the precursors to cooperatives. In 1955, Mao decreed that all farmers should "voluntarily" organize into large cooperatives. The cooperatives were overseen by party cadres and large portions of the output was turned over to the state. The early 1950s saw one of the largest peacetime mobilizations in history, prisoners of war, decommissioned Red Army soldiers and “reform through labor” convicts were sent to the Gobi Desert and western China as members of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, to build roads, canals, bridges and dams and transform a wasteland into a rich agricultural area of cotton, maize and rice, complete with its own cities. In some cases the condition were so sever that participants made furniture from sod bricks and used their own hair keep arm in the frigid winters.

Large centrally planned People’s Communes were established in late 1950s. At that time, when the "Great Leap Forward" was being launched, the first communes were created against the advise of Russian specialists. Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: The objective of the communes seems to have been not only the creation of a new organizational form which would allow the government to exercise more pressure upon farmers to increase production, but also the correlation of labor and other needs of industry with agriculture. The communes may have represented an attempt to set up an organization which could function independently, even in the event of a governmental breakdown in wartime. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1977, University of California, Berkeley]

The Communists had hoped that collectivism would help the huge Chinese population feed itself, but collectivism did not increase agricultural production. Within a short time it was clear this system wasn’t workable. Distribution was always a problem. Even during the Cultural Revolution when every able-bodied person in the country was put to the task of rasing food, food rotted in the fields and people starved.

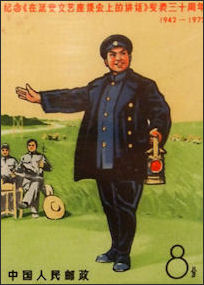

Dazhai commune poster

Scholar William McNeil once wrote: "The problem is the Chinese have never been able to organize collective effort with the sort of enthusiasm and efficiency of the Japanese. There is a kind of ruthless individualism in Chinese life, a competitiveness and acquisitiveness, that may make modern large-scale industrial organization difficult.”

Mao initially followed the Soviet model but became impatient with the slow pace of development and turned to radical mass movements like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. See History

In the 1960s and 70s, the land in effect belonged to a production team — made up of 20 to 40 households — whose members were co mpensated in shares of the collective harvest by a complex system of shared points.

Implementing Collectivization in China

The first major action to alter village society was the land reform of the late 1940s and early 1950s, in which the party sent work teams to every village to carry out its land reform policy. This in itself was an unprecedented display of administrative and political power. The land reform had several related goals. The work teams were to redistribute some (though not all) land from the wealthier families or land-owning trusts to the poorest segments of the population and so to effect a more equitable distribution of the basic means of production; to overthrow the village elites, who might be expected to oppose the party and its programs; to recruit new village leaders from among those who demonstrated the most commitment to the party's goals; and to teach everyone to think in terms of class status rather than kinship group or patron-client ties. [Source: Library of Congress *]

In pursuit of the last goal, the party work teams convened extensive series of meetings, and they classified all the village families either as landlords, rich peasants, middle peasants, or poor peasants. These labels, based on family landholdings and overall economic position roughly between 1945 and 1950, became a permanent and hereditary part of every family's identity and, as late as 1980, still affected, for example, such things as chances for admission to the armed forces, colleges, universities, and local administrative posts and even marriage prospects. *

The collectivization of agriculture was essentially completed with the establishment of the people's communes in 1958. Communes were large, embracing scores of villages. They were intended to be multipurpose organizations, combining economic and local administrative functions. Under the commune system the household remained the basic unit of consumption, and some differences in standards of living remained, although they were not as marked as they had been before land reform. Under such a system, however, upward mobility required becoming a team or commune cadre or obtaining a scarce technical position such as a truck driver's. *

Another Dazhai poster

Collective Farms, Communes and State Farms in China

Collectives were cooperative organizations in which farmers joined together to collectively raise crops on land worked in common. The farmers were paid in food (grain, vegetables, milk and meat) and money earned by the collective. Sometimes the term collective farm and commune was used interchangeably.

A commune is a groups of many cooperatives. A typical one embraced 60 villages and 20,000 members. All buildings, tools, machines, land and dwellings were owned by the commune. People worked in teams of 150 to 600 people and were paid a small wage a given clothing, food and housing. A typical rural Chinese family working on a agricultural commune earned about US$700 a year.

Communes were intended to function like small cities or towns. They had their own manufacturing capabilities and worked farmers like factory workers and kept people from migrating to the cities. If needed people on communes could be mobilized for large labor-intensive projects.

State farms were "factory type" farms that specialized mainly in one kind of crop or one kind of animal. They were set up and run by the state. Workers are treated the same as factory workers and paid a regular salary.

Large Collective Farms and Communes in China

Some collective farms in China were massive. "That commune was so large," one saying went, "that the person has to take a train to see the head of the committee." During the Cultural Revolution, some collective farms doubled as Chinese gulags for intellectuals and political prisoners.

Some 26,578 communes were established by 1958. One of the largest, State Farm No. 128 of the No. 7 Division (85 miles northwest of Urumqi) employed 17,000 people (almost all Han Chinese) and had military-style checkpoints, irrigated orchards and cotton fields as well as its own foreign affairs office, television station, oil refinery and enterprises for marketing crops and forestry products.

The Dazhai Commune in Shanxi province was one of the most famous communes in China. Reportedly built up from the ruins of great flood by 500 peasants, it boasted record grain productions and it provided a model for other communes across China. Over the years Danzhai was visited three times by Zhou Enai, twice by Deng Xiaoping as well as by Queen Beatrice of Netherlands, Pol Pot from Cambodia and leaders from Africa, Albania and East Germany. Later it was revealed that Dazhai was a sham. The record grain reports were fiction, production figures were exaggerated and the commune was subsidized. According to one writer, "Nowdays to many people the whole thing about Dazhai looks like a joke."

Yet another Dazhai poster

Collective Farm Organization in China

Authority for collective farms was determined by national laws or by rules drawn up by the collective farm. Each collective was run by a chairman-manager and board made up of Communist party loyalists theoretically elected by members of the collective. The collective farm chairman controlled all the resources and incomes.

Collectives, state farms and communes were often very inefficient. They often had armies of administrators, bookkeepers, veterinarians, dentists along with farmers that often wouldn’t hit the fields until 11:00am and sometimes did the threshing and winnowing by hand when their machines broke down.

Workers who followed the Soviet model worked in units called brigades or links that were directed brigade or link leaders. They often worked in teams of "labor-day" units, with certain tasks regarded as requiring more labor than others. A day of harvesting for example might be worth a whole labor day while a day of milking might be worth only half a day. Workers "earnings" were drawn against their future "income" of labor days.

At the end of each labor day units were tallied up by the brigade or link leader. At the end of the year, earnings and labor days are added up. If there was a surplus of labor days, a workers might receive a bonus of some sort.

As was true with factory workers, farm workers lacked incentives. A worker on a collective farm told the New York Times, since farmland belongs to the state "nobody is interested in working and producing on it." The man said he hated working on a the collective because his bosses were always telling him what to do.

Frank Dikötter, author of "The Great Famine" told Evan Osnos of The New Yorker: “The farmers who were herded into giant people’s communes had very few incentives to work. The land belonged to the state. The grain they produced was procured at a price that was often below the cost of production. Their livestock, tools, and utensils were no longer theirs. Often even their homes were confiscated.”

“Local cadres faced ever greater pressure to fulfill and over-fulfill the plan, having to drive the workforce in one merciless campaign after another,” Dikötter said. “In some places both villagers and cadres became so brutalized that the scope and degree of coercion had to be constantly expanded, resulting in an orgy of violence. People were tied up, beaten, stripped, drowned in ponds, covered in excrement, branded with sizzling tools, mutilated, and buried alive. The most common tool in this arsenal of horror was food, which was used as a weapon: entire groups of people considered to be too old, too weak, or too sick to work were deliberately banned from the canteen and starved to death. As Lenin put it, “He who does not work shall not eat.”

Benefits on a Collective in China

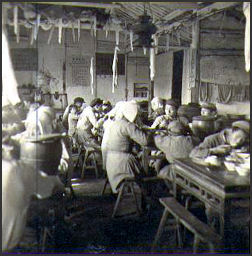

working on a collective in the 1950s

Collectives provided education, housing and transportation. Workers enjoyed a lifestyle similar to that of industrial workers, receiving paid vacation and social benefits such as maternity leave, health insurance, pensions and access to cultural events and continuing education.

Each farm family usually had a small plot of land on which it was allowed to grow vegetables and raise animals. The food produced was supposed to be for the family's consumption. Sometimes extra food was sold for extra cash on the black market or authorized private markets. Farmers who had access to urban markets could earn a considerable amount of money.

People who lived in communes sometimes slept in dormitories and ate in mess halls. But mostly they lived in one- or two-room houses or huts they sometimes built themselves. Until the 1970s these homes often lacked indoor plumbing and electricity. In forested areas these were made of wood. In the steppes they were made of mud brick. In other places they were often made of concrete slabs or brick. They houses often had thatch or sheet metal roofs.

Men only had two days off a week and women had three days off. Women were given a month off after the gave birth. There were special tasks for children and old people. Students often studied at school for five hours in the morning and worked in the afternoons. Measures were taken to keep people from migrating to the cities.

Life in a Chinese Commune

At communes and collectives the traditional family system was broken down. Some people slept in dormitories and ate in mess halls. Children were cared for in day care centers so their mothers could work. Old people were placed in special dwellings called "happy homes." To escape from this system many commune residents lived in small single-story brick houses they built themselves. Chinese peasant were generally allowed to have pigs and garden plots to raise food for themselves but not to sell.

commune life in the 1950s

Workers typically worked eight or nine hours a day and had weekends off. Sometimes when there was a lot of work to do they worked on the weekends. A typical day began at 5:00am when loudspeaker woke everyone up. After roll call, calisthenics and breakfast of dark bread and grits, people worked in the fields. Around 12:00noon the workers took a break for lunch, which was often made in a barn near the fields and served to workers near where they were working. It often consisted of stew or borscht served from a common pot served with potatoes, black bread and salted pork.

Work usually ended around 5:00pm. Dinner was served around 6:00. If there was time workers often worked their family garden plots. For entertainment there were self-criticism sessions, propaganda films, discussions of Marxism and gatherings and singing parties held in the collective’s recreation hall.

The work was often very tough. A woman told him, "After giving birth to first son I still had to keep working, making shoes for the soldiers, twenty shoes everyday for the soldiers. I kept my son in the corner and had to keep working." On first arrival to collective farm, one peasant told National Geographic, "We came here in March, walking from Urumqi. Nine days. We shot wild pigs and wild sheep for food."

Image Sources: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org ; Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; Commune in the 1950s, Ohio State University; Deng-era market, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Asia Obscura http://asiaobscura.com/ ;

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021