TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE

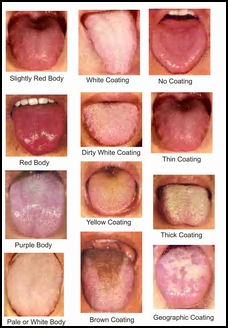

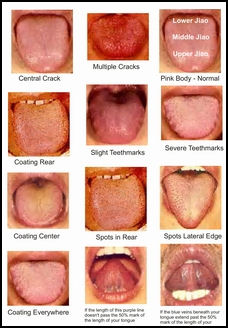

Tongue analysis, Image source:

acupunctureproducts.com Traditional medicine depends on herbal treatments, acupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion (the burning of herbs over acupuncture points), and "cupping" of skin with heated bamboo. Such approaches are believed to be most effective in treating minor and chronic diseases, in part because of milder side effects. Traditional treatments may be used for more serious conditions as well, particularly for such acute abdominal conditions as appendicitis, pancreatitis, and gallstones; sometimes traditional treatments are used in combination with Western treatments. A traditional method of orthopedic treatment, involving less immobilization than Western methods, continued to be widely used in the 1980s. [Source: Library of Congress]

The World Health Organization estimates that four fifths of all people in the world still rely chiefly on traditional medicines, mostly herbs and plants. According to AFP Such therapies have been used in China for more than 3,000 years, but have risen in popularity outside Asia in recent decades and now amount to a global industry worth hundreds of millions of dollars a year, according to the study in PLoS Genetics.

Most Chinese hospitals have at least one acupuncturist and herbalist on the staff and dispense more than 300 different kinds of medicinal herbs. The number of traditional Chinese medicine doctor rose from 150,000 in 1985 to 250,000 in 1995 to 270,000 in 2005, while the number of Western doctors rose from 550,000 to 1,250,000 to 1.7 million in the same period. In 1945, it was estimated that there were 800,000 traditional Chinese doctors in China and only 12,000 Western doctors.

The domestic Chinese medicine market in China is valued at more than $1 billion. Chinese medicine is protected by the Chinese constitution and is covered by national insurance. It is generally cheaper than Western medicine and tends to be relied on more in the countryside among older people in part because of the lower cost.

In China, there is a growing interest in traditional medicine among sophisticated urban people as celebrities promote their favorite cures and a number of books, DVDs and website are available. Lectures are organized by companies, health clubs and community centers. Popular dramas such as “The Great Royal Doctor”, about an Imperial era bonesetter, attract large audiences and bring attention on traditional institutions like the 200-year-old Pingle Style Bone-Setting School.

Ton Ren Tang, a 360-year-old apothecary that once served China’s emperors, is now a major Chinese medicine chain with over 1,000 outlets.

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): National Center for Complimentary and Alternative Medicine on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) /nccam.nih.gov/health ; National Center for Biotechnology Information resources on Chinese Medicine ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ; Skepticism of Chinese Medicine quackwatch.org ; Chinese Medicine Chinese Text Project ; Wikipedia article on Traditional Chinese Medicine Wikipedia ; American Journal for Chinese Medicine ejournals.worldscientific.com

Good Websites and Sources on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM): National Center for Complimentary and Alternative Medicine on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) /nccam.nih.gov/health ; National Center for Biotechnology Information resources on Chinese Medicine ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ; Skepticism of Chinese Medicine quackwatch.org ; Chinese Medicine Chinese Text Project ; Wikipedia article on Traditional Chinese Medicine Wikipedia ; American Journal for Chinese Medicine ejournals.worldscientific.com

Acupuncture: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mayo Clinic on Acupuncture mayoclinic.com ; National Institute of Health (NIH) on Acupuncture nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/acupuncture ; American Association of Acupuncture and Oriental Medicineaaaomonline.org ; On Qi Gong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Classical text sources neigong.net ; Qi Gong Institute qigonginstitute.org ; Qi Gong association of America /www.qi.org ; Skeptic’s Dictionary on Qi Gong skepdic.com More Skepticism of Qi Gong quackwatch.org ; On Moxibustion : Acupuncture Treatment.com acupuncture-treatment.com ; Moxibustion Video YouTube ; Wikipedia article on Fire Cupping Wikipedia ; Article on Cupping itmonline.org

QI, YIN-YANG AND THE FIVE FORCES AND CHINESE BELIEFS ABOUT HARMONY AND COSMOLOGY factsanddetails.com; QI AND QI GONG: HISTORY, POWER, MASTERS, MEDITATION factsanddetails.com; QI GONG AND HEALTH factsanddetails.com; TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE DOCTORS, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT factsanddetails.com; INGREDIENTS IN CHINESE MEDICINE: GINSENG, MA HUANG, GOJI BERRIES AND GINKGO BILOBA factsanddetails.com; ARTEMISININ AND MALARIA MEDICINES, TREATMENTS AND DRUGS factsanddetails.com; CATERPILLAR FUNGUS factsanddetails.com; TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE VERSUS WESTERN MEDICINE factsanddetails.com; TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE, WESTERN DRUGS, SAFETY AND STUDIES factsanddetails.com; ACUPUNCTURE: TREATMENTS, RESEARCH AND FIRST HAND EXPERIENCES factsanddetails.com PET ACUPUNCTURE factsanddetails.com; MOXIBUSTION AND CUPPING factsanddetails.com ;SEAHORSES, DEER ANTLERS, ANIMAL PARTS, ENDANGERED ANIMALS AND CHINESE MEDICINE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary” by Maoshing Ni Amazon.com; “Medicine in China: A History of Ideas” by Paul U. Unschuld Amazon.com; “Chinese Traditional Herbal Medicine Volume I Diagnosis and Treatment by Michael Tierra, Lesley Tierra Amazon.com; “The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text” by Giovanni Maciocia CAc Amazon.com; “Basic Theories of Traditional Chinese Medicine” (International Acupuncture Textbooks) Amazon.com; Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine by Yan Wu , Warren Fischer, et al. Amazon.com; “Foundations of Theory for Ancient Chinese Medicine: Shang Han Lun and Contemporary Medical Texts” by Guohui Liu and Charles Buck Amazon.com; Qi and Qi Qong “The Way of Qigong: The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing” by Kenneth S. Cohen Amazon.com; “A Brief History of Qi” by Yu Huan Zhang and Ken Rose Amazon.com; “Encounters with Qi: Exploring Chinese Medicine” by David Eisenberg and Thomas Lee Wright Amazon.com; “Qigong Empowerment: A Guide to Medical, Taoist, Buddhist and Wushu Energy Cultivation” by Master Shou-Yu Liang and Mr Wen-Ching Wu Amazon.com

Philosophy Behind Chinese Medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine is an ancient system that places an emphasis on the whole body rather than specific ailments. It medicine emphasizes prevention rather than cure and views the cause of illness as a weak level of energy, which can be treated with a strength-giving restorative medicine. It focuses on "promoting wellness" and treating diseases by locating disharmonies and imbalances and restoring harmony and balance. Agents that cause disease are regarded as belonging to the same universe as the body and treatment is not a mater of killing or getting rid of them but in restoring their balanced place in the universe.

Ma Kou carrying medicinal plants

Practitioners of Chinese medicine believe that health is regulated by a rhythm of “yin” (the passive female force) and “yang” (the active male force), which in turn are influenced by the "five elements" (fire, water, tree, metal and soil), the “six pathogenic factors,”(cold, wind, dryness, heat, dampness and fire) and the “seven emotions” (joy, anger, anxiety, obsession, sadness, horror and fear). In healthy people these forces are in harmony. In unhealthy ones they are out of balance. Too much or too little food, drink, work or exercise can also throw the whole system out of wack. Many Chinese believe that hip problems can be caused by excessive drinking and hormone imbalances.

Opposing yin and yang forces are part of the body's qi. Health problems are considered a manifestation of an imbalance of yin and yang, that disrupts a person's qi. Disease is believed to be caused when a patient’s “qi” (pronounced "chee") is too weak, out of balance or blocked. Qi is a "vital force" present thought out the universe that makes life possible. Qi flows through the body along 14 major channels, or “meridians.” The task of a Chinese doctor is make the qi strong by restoring its balance with the universe and harmonizing the internal rhythms of the patient with the rhythms of his or her environment. Medical problems are approached holistically. Knowledge of internal anatomy is not necessary because the body gives external clues for imbalances on the inside.

Explaining why he takes Chinese medicine one policeman in Beijing told the New York Times, “It is a part of the Chinese tradition to drink these medicines, and at the very least it gives you peace of mind.”

History of Chinese Medicine

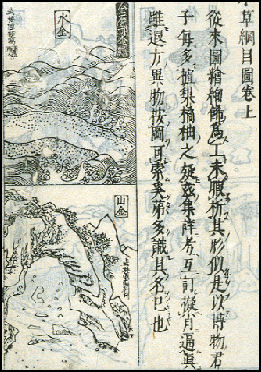

Bonchogangmok

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “The Chinese record dates back to the third century B.C., when healers began analyzing the body, interpreting its functions, and describing its reactions to various treatments, including herbal remedies, massage, and acupuncture. For more than 2,200 years, generations of scholars added to and refined the knowledge. The result is a canon of literature dealing with every sort of health problem, including the common cold, venereal disease, paralysis, and epilepsy. This knowledge is contained in books and manuscripts bearing such enigmatic titles as The Pulse Classic (third century), Prescriptions Worth a Thousand Pieces of Gold (seventh century), and Essential Secrets From Outside the Metropolis (eighth century). [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, January 2019]

Traditional medicine remained the primary form of health care in China until the early 20th century, when the last Qing emperor was overthrown by Sun Yat-sen, a Western-trained doctor who promoted science-based medicine. Today Chinese physicians are trained and licensed according to state-of-the-art medical practices. Yet traditional medicine remains a vibrant part of the state health care system. Most Chinese hospitals have a ward devoted to ancient cures. Citing traditional medicine’s potential to lower costs and yield innovative treatments, not to mention raise China’s prestige, President Xi Jinping has made it a key part of the country’s health policy. He has called the 21st century a new golden age for traditional medicine.

Many of the basic principals of Chinese medicine were described more than 2,100 years ago in the “Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine”. It includes a map of qi lines and acupuncture points. According to legend the mythical emperors Huang-di and Shen Nung founded the two main forms of Chinese medicine — acupuncture and pharmacopeia — in 2,700 B.C. through their interaction with extraordinary creatures such as dragons and turtles. Eye drops made from the mahuang plant, which contains ephedrine hydrochloride, were used in China in 3000 B.C. Emperor Qin devoted a lot of time, energy and resources searching for an elixir of immortality in the 3rd century B.C.

Zhang Zhongjing (Chang Chungching, Zhang Ji, A.D. 152–219) was a celebrated Chinese physician, pharmacologist, inventor, and writer during the later years of the Han dynasty. He chronicled medicinal advances up to his time and laid out medication principles that form the basis of Chinese medicine and is regarded by some as the father of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The 7th century physician Sun Dsu-miao is regarded as the Hippocrates of China. He asserted that doctors should treat poor patients just as well as the rich. The medical guide “New and More Detailed Pharmacopoeia of Khai-Pao reign-Period” was widely in use in A.D. 1000. Marco Polo wrote of rhubarb being used in China as a laxative in the 11th century. Li Shizhen (Shichen, 1518–93), an outstanding pharmacologist, wrote a monumental Materia Medica. Written between 1552 and 1578 this huge book comprises fifty-two parts and describes 1,871 plant, animal, and mineral substances, from which it suggests no less than 8,160 medical prescriptions. Among them are chaulmoogra oil (derived from a tree native to Southeast Asia), which is still the only known means for treating leprosy, and ephedrine, a plant drug introduced to the West that is now widely used for treating colds. Ephedrine hydrochloride is still used to treat minor eye irritations today and is often the source of meth made home meth labs. .

"Barefoot doctors," who were first sent out into the countryside by Mao Tse-tung after the revolution, used one of the China’s most successful herbal medicines — pumpkin seeds — to rid patients of worms. Today the treatment is also used in Africa to combat snail fever, or schistosomiasis. A dispensary used by the Qing emperors is still patronized by customers in Beijing who use the same medicines as emperors mixed according secret formulas.

Traditional Chinese Medical Texts

Artemisia annua which is now used to make anti-malaria medicines was first mentioned as hemorrhoid treatment in the 168 B.C. medical treatise “Fifty-Two Remedies” and described by Ge Heng (283-363), a Taoist priest preoccupied with the search for elixirs of immortality, in his "Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergency Treatments."

The National Palace Museum in Taipei is home to a rich collection of traditional medical texts, and many of which were once part of the Qing imperial collections of books or official compilations and others are rare editions uncovered by late Qing scholars. They cover methods to prevent disease at its root and food therapy and offer various recommendations for the cultivation of good health and the quest for longevity. As the saying has it, "human life is precious, and even more valuable than a thousand taels of gold," public health has long been an important part of governmental institutions, and advancements in medical and pharmacological theories have helped to spur the progress of medical culture and practices. development of traditional Chinese medical scholarship and its interactions with human lives, diseases, religion and institutions. Some texts show the mutual influence between Chinese, Japanese, and Korean medicine. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Important gynecological and pediatric works included “Furen Daquan Liangfang” (“Good Prescriptions from the Great Compendium on Women's Medicine”), “Chanbao Zhufang” (“Recipes for Child Birth”), “Luxin Jing” (“Canon of Infantile Fontanel”), “Xiaoer Yaozheng Zhenjue” (“Key Techniques for Treating and Examining Children”), “Waitai Miyaofang”(“Arcane Essentials from the Imperial Library Formularies”) and “Xinkan Renzhai Zhizhi Xiaoer Fanglun” (“Newly Printed Effective Recipes for Children from Yang Renzhai”).

Among the text that deal with putting the human body in perspective are “Xuanmen Maijue Neizhao Tu”(“Diagnosing and Treating Diseases through Viscera”), “Qipo Wuzangjing”(“Jivaka's Five Viscera Classic”) and “Huangdi Hamajing”(“Yellow Emperor's Toad Canon”). The history of disease is covered in “Songfeng Shuoyi”(“Songfeng on Epidemics”), “Xiuxiang Fanzheng”(“Illustrated Miao Medical Book”) and “Zhubing Yuanhou Lun”(“Treatise on the Origins and Manifestations of Various Diseases”)

The world of ancient pharmacology is showcased in medical classics like “Jingshi Zhenglei Daguan Bencao” (“Pharmacopoeia of the Daguan Reign”) and “Bencao Gangmu” (“The Compendium of Materia Medica”). They contain illustrations of herbal medicine and horse bezoars, which were ingredients in Chinese medicine. In addition, Japanese texts including “Yakushushō” (“Annotations of Medical Plants”) and “Honzō Wamyō” (“Japanese Names of Medical Herbs”), as well as Korean titles such as “Uibang Yuchwi” (“Classified Collection of Medical Prescriptions”) and “Hyangyak Jibseongbang” (“Compendium of Folk Medical Prescriptions”) are testament to the far-reaching influence and dissemination of traditional Chinese medicine. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Religion and medicine are touched on “Chifeng Sui”(“Marrow of the Red Phoenix”), “Yinshan Zhengyao”(“Proper and Essential Things for Beverages and Food”) and “Xinke Yangsheng Leizuan”(“New Block-printed Classified Compendium on Nourishing Life”). Medicine and the State are dealt with in “Taiping Huimin Hejiju Fang”(“Formulary to Benefit the People from the Pharmaceutical Bureau of the Taiping Reign”), “Qinding Gujin Tushu Jicheng”(“Imperially Endorsed Complete Collection of Graphs and Writings of Ancient and Modern Times”) “Chunhuage Tie”(“Model Calligraphy of the Chunhua Archive”)

Traditional Chinese Views About Health and Disease

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “People cultivate health to prolong life and stay healthy as they age. Starting in the Song dynasty, the shaping and promotion of the traditional Chinese approach to health cultivation increasingly involved the literati, and by the late Ming dynasty the cultivation of health was being treated as a commodity that could be commercialized, thus taking on a material dimension. The dizzying array of health tips captivated the minds of people in ancient China, and many of these methods are still widely practiced today, and examples include the Taijiquan and Qigong that derived from the fitness exercises of the “Wuqinxi” (“Five Animal Dances”) and the “Baduanjin” (“Eight Pieces of Brocade”). In addition, food therapy and medicinal cuisine still claim many adherents and have evolved over time. In times past knowledge and techniques for the cultivation of health in daily life were disseminated through texts such as “Yinshan Zhengyao” (“Proper and Essential Things for Beverages and Food”), “Zunsheng Bajian” (“Eight Treatises on the Preservation of Life”), and “Shuoqin Yanglao Xinshu” (“A New Book on Supporting Aged Parents”). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“According to traditional Chinese medical theory, illness is caused by exposure to the Six Pernicious Influences (excessive wind, cold, heat, damp, dryness and fire), disturbances of the Seven Emotional States (joy, anger, anxiety, thought, grief, fear and fright), exhaustion, over-indulgence in sex and insanitary diet. Such influences lead to imbalances in yin and yang, internal and external, cold and hot, as well as weak and strong, qi (vital energy) and blood, which are eventually manifested in disorders of the five viscera and six bowels, resulting in a variety of diseases. In history men have suffered from a wide range of diseases, including typhoid fever, warm disease, beriberi, emotional disorders, leprosy, syphilitic sores, smallpox, bubonic plague, dysentery and cholera. The history of human diseases can be traced through an examination of such medical texts as “Sanyin Jiyi Bingzheng Fanglun” (“Treatise on the Three Categories of Pathogenic Factors”), “Wenyilun” (“Treatise on Febrile Epidemics”) and “Xiuxiang Fanzheng” (“Illustrated Miao Medical Book”). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

According to the “Discussion on Cold-Induced Disorders” by Jan Jung Gyung, written in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), colds are caused by the invasion of Outer Coldness on the body, a process that occurs in six stages. The first stage of a cold, known as “tae-yang”, is characterized by stiffness of the head and neck, shivers, and a "floating pulse." The second state, “yang-myung”, occurs when the Outer Coldness infiltrates the area governed by the Stomach Vessel. Symptoms include a dry throat and dizziness near the eyes. Treatment, which is still followed today is based on halting the symptoms at each stage, preventing the next one from occurring.

Traditional Chinese Medicine, Religion and the State

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Throughout history almost every religion has used medicine to promote its faith, and each religion has a distinct view of disease and approaches to treatment. Believers often seek religious guidance to help cope with diseases. Although medical practitioners tend to see religious medicine as no more than superstition, patients themselves nevertheless regard medicine backed by religious belief as an effective measure to relieve anxiety and unease, or even strengthen confidence in their recovery, which is why many people, past and present, have chosen this path. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Medical discourses include Buddhist and Taoist classics such as “Suvar aprabhāsa Sūtra” (“The Golden Light Sutra”) and “Yunji Qiqian” (“Seven Tablets in a Cloudy Satchel”), illustrations of folk religion and medicine in “Shen zhou Huabao” (“Fiction Pictorial”) and “Tuhua Xinwen” (“The Pictorial News”), as well as archival materials containing descriptions of medical activities practiced by followers of secret religions, to demonstrate the role of religion and spirituality in the history of medicine.

“The governments of successive dynasties tended to see medical matters as an integral part of state administration. The government's involvement in medical matters mainly took place in the following areas: setting up medical institutions, compiling medical texts, engaging in disease control, and cracking down on shamans. Important works include “Taiping Huimin Hejiju Fang” (“Recipes to Benefit the People from the Pharmaceutical Bureau of the Taiping Reign”) and the medical section of the “Gujin Tushu Jicheng” (“Complete Collection of Pictures and Books of Ancient and Modern Times”), as well as documentation from official archives. It provides an overview of government control of medical activities and government efforts to produce and disseminate orthodox medical knowledge, as a gateway to understanding the role of the state in the development of traditional medicine. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Chinese Herbal Medicine

Endurance and strength medicine Chinese herbal remedies are regarded as strength-giving restorative medicines that prevent rather than cure illnesses and rejuvenate energy to fight illnesses caused by low energy levels. Many Chinese take herbal medicines for things like back aches, nausea, headaches, colds, flus, bronchitis, asthma, sore throats. and problems that require long-term treatment.

Herbalists believe that Chinese herbs are used to treat the entire body holistically rather than target a certain organ or disease. The ones used to treat migraine headaches are said to be particularly good. Another benefit of herbal medicines is that they have relatively few side effects in the short run. They generally don't cause allergic reactions like penicillin. Some herbs are dangerous if used frequently over a long period because some of them contain mild toxins that can damage the liver, kidneys or other organs.

Botanists in China have patiently catalogued over 28,000 plant species of Chinese plants into 120 volumes. Over 20 percent of these are used in Chinese medicine. Common Chinese herbal medicines include hedysarum, ginseng, Chinese matrimony berry and licorice. Popular restorative medicines include honey, aloe, kale, brown rice, squeezed vegetable extracts, arrowroot, and red flower seeds.

The most extensive arrays of Chinese herbal remedies are found on Ko Shing Street in Hong Kong and the vast herb market in Puning, a town on China’s southern coast.

Bozhou, Center of Traditional Chinese Medicine

Bozhou, a city in northwestern Anhui province about 600 kilometers northwest of Shanghai,

is regarded as the Center of Traditionally Chinese Medicine in China and the world.

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “If you buy Chinese herbs on Amazon, there’s a decent chance that they passed through the eastern city of Bozhou, the center of the Chinese medicine universe. Every day 10,000 traders sell thousands of different products to 30,000 buyers from all over Southeast Asia, all of them jammed in a colossal structure resembling a domed football stadium. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, January 2019]

“The morning I visit Bozhou, the market is already a raucous hive of commerce. I zigzag up and down endless aisles, one cavernous room after another, each chock-full of barrels, sacks, pallets, and wheelbarrows heaped with wares derived from what appears to be nearly every plant, mineral, and creature on the planet, including exotic items like deer penises, human placentas, water buffalo bones, and dried seahorses. A section the size of a grocery store is devoted to the cure-all ginseng root — red and white, wild and cultivated, fresh and dried, ranging in price from a few dollars to several thousand. In the insect section, I stop counting the different centipede species at 11.

“I’ve come here to see the source of most Chinese herbal drugs marketed around the world. You can find seemingly every ingredient here, but you’d have little clue how it was grown or where. Sure enough, I easily find all four ingredients for PHY906 — but all are sold by resellers who know little of the herbs’ origins. Before I leave the market, one ingredient catches my eye. In a section near deer antler velvet, I see a glass case with a row of bottles containing yellowish liquid. I ask the vendor what it is, and he gets his neighbor to translate. “Take from bear,” the man says. “Very good.”

Market for Chinese Medicinal Herbs

In 2017 China's medicinal herb-growing industry generated about $25 billion. The cost of herbal medicines has risen significantly as a result of higher labor prices, increased demand in China where incomes are higher and more people can afford them and shortages of some ingredients. As Chinese have become affluent the demand for certain herbs, roots and animal products has risen, causing heir prices to soar. A small box of rare root, for example, that is boiled in a soup and eaten to strengthen the lungs, sold for $600 in 2006, four times the price in 2004.

Many people sell herbal remedies in the streets of China. Describing a Tibetan medicine man at a market in Guizhou Province of southern China, Patrick Tyler wrote in the New York Times, he "displayed his wares on a red cloth laid on the ground before him. On porcelain saucers lay his herbal delights: red angel hair from a Tibetan flower, yellow sawdust from a medicinal tree...While wrapping up a bundle of herbs and animals parts, which sold for the equivalent of 75 cents, the medicine man said, “Now you should put this in liquor and drink it every day. It is very good for your rheumatism.”

Dried notoginseng flowers are a key and lucrative ingredient used in many herbal formulas. Because of the potential for profit, large companies have acquired much of the farmland in Wenshan where the flowers are produced and now employ organic methods to grow them. [Source: National Geographic, January 2019]

Growing Medicinal Herbs in China

Reporting from northern Anhui Province, near Bozhou where many Chinese herbal medicines are grown in farms, Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “I can say this part of China looks like a version of Kansas — tabletop flat with neatly furrowed fields as far as I can see. But among the wheat, rice, and rapeseed are plots of herbs tended by thousands of farmers. As the global appetite for herbal remedies has grown, Chinese farmers have devoted increasing amounts of acreage to hundreds of medicinal plant species. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, January 2019]

“When we finally get to one of the fields that yielded PHY906, I’m frankly a little disappointed. Except for the fact that the farmer, Chen, is speaking Mandarin, he might as well have been from Kansas. Wearing muddy boots, a heavy parka, and a baseball cap, he pulls out his iPhone and asks Siri to translate the Chinese name of his crop into English. “Peony,” she answers.

“As we tour his fields of peony and skullcap bushes, he explains his crop rotations, soil and water analyses, planting and harvesting protocols. Before shipping the herbs, he says, technicians from Sun Ten perform multiple tests to reconfirm the species; screen for microorganisms, toxins, and heavy metals; and complete other quality checks. “You’ve heard of farm to table,” Peikwen says. “The idea here is farm to bedside.” I tell him that sounds like a marketing slogan. But it’s true, says Chen. “Most companies making herbal remedies don’t get them from farms like this. They get them from Bozhou.”

Image Sources: Tqnyc; All Posters com; ; Wikipedia; Compassionate Dragon Healing; Accupuncture Products; Iron Palm Arts; WWF; Ciao Su Nature Products; South Aquaculture

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022