TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE IN THE MODERN WORLD

Chinese medicine shop

China has 1.1 million certified doctors of Western medicine, versus 186,947 traditional practitioners. It has 23,095 hospitals, 2,889 of which specialize in Chinese medicine. There is increasing global demand for Chinese Traditional Medicine (TCM) especially as interest in it grows in the United States and Europe. According to AFP: China's highly-fragmented TCM market is led by firms such as Tasly Pharmaceutical Group Co Ltd and China Resources Sanjiu Medical & Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, which each have billion dollar-plus annual sales. [Source: AFP, December 23, 2012; Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 10, 2015]

Although the practice of traditional Chinese medicine was strongly promoted by the Chinese leadership and remained a major component of health care, Western medicine was gaining increasing acceptance in the 1970s and 1980s. The goal of China's medical professionals is to synthesize the best elements of traditional and Western approaches. In practice, however, this combination has not always worked smoothly. In many respects, physicians trained in traditional medicine and those trained in Western medicine constitute separate groups with different interests. For instance, physicians trained in Western medicine have been somewhat reluctant to accept "unscientific" traditional practices, and traditional practitioners have sought to preserve authority in their own sphere. Although Chinese medical schools that provided training in Western medicine also provided some instruction in traditional medicine, relatively few physicians were regarded as competent in both areas in the mid- 1980s. [Source: Library of Congress]

In Asia there are special medical schools to train doctors in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) or the local equivalents. Traditional medicine doctors in Asia are licensed by the government. Universities have acupuncture departments. Doctors and pharmacists practicing Chinese medicine have to attend medical school and pass exams just like doctors who practice Western medicine.

A typical conference on Oriental medicine is attended by over 2,000 doctors from 30 countries. Lectures are given by doctors from China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan on topics like "The Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease with Traditional Chinese Medicine," "Patho-physiological Analysis of Blood Stagnant Syndrome” and the "Evaluation of Efficacy of Bronchial Asthma by Clinical Trials, Laboratory Tests."

Only recently have Western doctors begun to study Asian medicines with carefully controlled studies. In September 2002, 1,500 researchers from 28 countries presented more than 1,000 research on traditional Chinese treatments, most of them using Western research methods. The research found that Chinese medicine is most effective treating chromic ailments such as digestive disorders, recurring migraines, menopausal symptoms. in which Western medicine is the most ineffective. The study of Chinese medicines is difficult because remedies are often blends of several herbs.

TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE: HISTORY, HERBS, PHILOSOPHY AND TEXTS factsanddetails.com; QI, YIN-YANG AND THE FIVE FORCES AND CHINESE BELIEFS ABOUT HARMONY AND COSMOLOGY factsanddetails.com; QI AND QI GONG: HISTORY, POWER, MASTERS, MEDITATION factsanddetails.com; QI GONG AND HEALTH factsanddetails.com; TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE DOCTORS, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT factsanddetails.com; INGREDIENTS IN CHINESE MEDICINE: GINSENG, MA HUANG, GOJI BERRIES AND GINKGO BILOBA factsanddetails.com; TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE, WESTERN DRUGS, SAFETY AND STUDIES factsanddetails.com; ACUPUNCTURE: TREATMENTS, RESEARCH AND FIRST HAND EXPERIENCES MOXIBUSTION AND CUPPING factsanddetails.com ;SEAHORSES, DEER ANTLERS, ANIMAL PARTS, ENDANGERED ANIMALS AND CHINESE MEDICINE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Medicine in China: A History of Ideas” by Paul U. Unschuld Amazon.com; “Chinese Traditional Herbal Medicine Volume I Diagnosis and Treatment by Michael Tierra, Lesley Tierra Amazon.com; “The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Medicine: A New Translation of the Neijing Suwen with Commentary” by Maoshing Ni Amazon.com; “The Foundations of Chinese Medicine: A Comprehensive Text” by Giovanni Maciocia CAc Amazon.com; “Basic Theories of Traditional Chinese Medicine” (International Acupuncture Textbooks) Amazon.com; Practical Therapeutics of Traditional Chinese Medicine by Yan Wu , Warren Fischer, et al. Amazon.com; “Foundations of Theory for Ancient Chinese Medicine: Shang Han Lun and Contemporary Medical Texts” by Guohui Liu and Charles Buck Amazon.com; Qi and Qi Qong “The Way of Qigong: The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing” by Kenneth S. Cohen Amazon.com; “A Brief History of Qi” by Yu Huan Zhang and Ken Rose Amazon.com; “Encounters with Qi: Exploring Chinese Medicine” by David Eisenberg and Thomas Lee Wright Amazon.com; “Qigong Empowerment: A Guide to Medical, Taoist, Buddhist and Wushu Energy Cultivation” by Master Shou-Yu Liang and Mr Wen-Ching Wu Amazon.com

China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences

Located on a shady street in the Old City of Beijing, the Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACMS), according to the New York Times, “is spread over a city block and welcomes visitors with an incongruous juxtaposition: a six-foot high quotation from Chairman Mao facing bronze statues of gowned doctors from antiquity who devised esoteric theories to heal the human body.[Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 10, 2015]

The Chinese Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CACMS) was established in 1955 and previously named the Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine (CATCM). It is a comprehensive institution for scientific research, clinical medicine and medical education on traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which is directly under the leadership of the State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (SATCM). [Source: Wiki China,org

At present, the CACMS is the largest research organization on Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in China and covers all the disciplines of TCM, advanced equipment and solid scientific research strength. It has under embraces 13 institutes, six hospitals, as well as a graduate school, the Publishing House of Ancient Chinese Medical Books and the Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. The CACMS has a staff of over 4,000, including 3,200 professionals in various fields. In addition, three WHO collaborating centers for traditional medicine have been set up through the cooperation and joint efforts between WHO and CACMS in the fields of clinical medicine and information, acupuncture and Chinese materia medica. Moreover, the World Federation of Acupuncture and Moxibustion Societies (WFAS), the Chinese Association of Integration of Traditional and Western Medicine (CAIM) and the Chinese Association of Acupuncture and Moxibustion (CAAM) are attached to the Academy.

Traditional Chinese Medicine in Republican and Communist-Era China

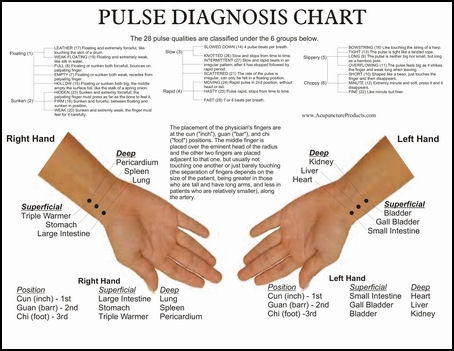

Image source: acupunctureproducts.com Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: “After a series of lost wars and national humiliations Chinese reformers and revolutionaries” in the late 19th and early 20th centuries “began jettisoning almost everything from the country’s long past: its political and religious systems; its architecture and urban planning; its national dress and its lunar calendar. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 10, 2015]

“Traditional medicine came in for especially harsh criticism. Some of the country’s most famous writers, like Lu Xun, Lao She, and Ba Jin, pilloried it as exemplifying everything wrong with the country. Its theories were obscure, its outcomes unproven, and most of all it was “unscientific” in a country that was beginning to worship science as the cure to all ills. “Everyone at that time agreed that Chinese medicine had no future,” said Paul Unschuld, a historian of Chinese medicine at the Charité Hospital in Berlin. “Ideas like yin-yang, the Five Elements — all of that was considered backwards.”

“When the Communists took over China in 1949, however, the country had few Western hospitals. A few years later, Mao Zedong declared that “Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house.” The praise, though, came with a caveat: It must modernize. That meant setting up traditional Chinese hospitals, schools and research facilities like the academy in Beijing.

“But money has flowed overwhelmingly toward Western medicine. In the Mao era, rural health care workers — “barefoot doctors” — were often traditional practitioners, which raised the profile of Chinese medicine. After Mao’s death and with growing prosperity, the government doubled down on Western medicine. Traditional Chinese Medicine is “part of the nation, but the nation of China defines itself as a modern nation, which is tied very much to science,” said Volker Scheid, an anthropologist at the University of Westminster in London. “So this causes a conflict.”

Debate Over Chinese Medicine

There is an ongoing debates over the scientific validity and practical utility of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) and its place in a world dominated by Western medicine. Some Chinese medicines are regarded as little more than snake oil tonics. Yet others are remedies that have been used successfully in Chinese hospitals and clinics for hundreds of years to treat a number of maladies. Many Chinese think TCM should not be respected at all. He Zuoxiu, a member of the prestigious Chinese Academy of Sciences, told the New York Times that the ancient pharmacopoeia should be mined, but the underlying theories that identified these herbs should have been discarded long ago. “I think for the future development of Chinese medicine, people should abandon its medical theory and focus more on researching the value of herbs with a modern scientific approach,” Dr. He said.

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “Few subjects ignite more heated debate in health circles than traditional Chinese medicine. It’s further complicated by the work of researchers like Paul Iaizzo and many others who are looking at traditional cures through the lens of cutting-edge science and finding some interesting surprises — surprises that could have profound impacts on modern medicine. Cultures from the Arctic to the Amazon and Siberia to the South Pacific have developed their own medicine chests of traditional cures. But China, with one of the oldest continuous accumulations of documented medical observations, offers the biggest trove for scientists to sift through. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, January 2019]

“You’ll also find doctors who denounce traditional Chinese medicine as pseudoscience and quackery, pointing to some of its most outlandish claims, like the ancient practice of prescribing firecrackers to chase away demons, or mysterious concepts still embraced, such as a nebulous life force called qi (a term translated literally as “the steam that rises from the rice”). Others rail against its use of animal parts and warn against the potential dangers of its herbal formulas. “Rarely do you find anyone who looks at it objectively,” says medical historian Paul Unschuld. A leading authority on the history of Chinese medicine — and often an unsparing critic of the way it’s interpreted — he has collected and translated hundreds of ancient medical texts and is working with a Chinese-German startup to study them for ideas about treating a variety of illnesses, including epilepsy. “People generally see only what they want to see,” he says, “and fail to fully examine its merits and its faults.”

“I encountered this hornet’s nest firsthand when I wrote a story about rhinos being poached for their horns. According to ancient Chinese formulas, rhino horn can be used to treat fever and headaches. In Vietnam I found patients using it to treat hangovers and the side effects of chemotherapy. Multiple scientific studies have determined that rhino horn, which is made of keratin (the same substance as human fingernails), induces little to no discernible pharmacological effects when ingested. But some patients using rhino horn may find relief because of the placebo effect. After the story was published, I got letters from readers angrily denouncing Chinese medicine as “ignorant,” “cruel,” and akin to “witchcraft.”

“Such criticisms aren’t without merit. Rhino horn sales in Asia are a primary factor pushing rhino populations toward extinction. In addition to bears, many other animals — including several threatened species such as tigers, leopards, and elephants — are poached in the wild or farmed for their parts. But modern medicine has its own controversial practices. The effectiveness of many popular antidepressant drugs remains hotly debated, with some studies showing they are barely more effective than placebos. Yet these drugs are extensively marketed and widely prescribed by physicians, generating billions of dollars in revenue. (This isn’t to say depression drugs don’t work. If a patient’s symptoms are relieved, then one can argue they work. But the chemicals in the pills themselves may not always be the source of the relief, just like the chemicals in rhino horn aren’t necessarily the source of relief for patients who take it.) When considered alongside other notable examples — the overprescription of opioids, doctor-endorsed fad diets, and questionable surgeries — Western indignation over traditional Chinese medicine can seem more hypocritical than Hippocratic.

Chinese Reaction to Tu Youyou Winning the Nobel Prize

ginseng In 2015 when China basked in its first Nobel Prize in science, Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times:“few places seem as elated, or bewildered, by the honor” given to Tu Youyou, for extracting the malaria-fighting compound Artemisinin from the plant Artemisia annua “as the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences. Traditionalists say the award, in the “physiology or medicine” category, shows the value of Chinese medicine, even if it is based on a very narrow part of this tradition. “I feel happiness and sorrow,” said Liu Changhua, a professor of history at the academy. “I’m happy that the drug has saved lives, but if this is the path that Chinese medicine has to take in the future, I am sad.”[Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 10, 2015]

“The reason, he said, is that Dr. Tu’s methods were little different from those used by Western drug companies that examine traditional pharmacopoeia around the world looking for new drugs. In fact, in its award, the Nobel committee specifically said it was not honoring Chinese medicine, even though Artemisia has been in continuous use for centuries to fight malaria and other fevers, and even though Dr. Tu said she figured out the extraction techniques by reading classical works. Instead, it said it was rewarding Dr. Tu for the specific scientific procedures she used to extract the active ingredient and create a chemical drug.

“The conundrum” over the award “was on display at a hastily called news conference hosted by the academy’s Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, where Dr. Tu worked. Chinese reporters had been badgering the institute for days for information on Dr. Tu. Finally, officials announced the briefing. For an hour, Chinese journalists asked two officials from the institute for any sort of information on Dr. Tu: what was she like (blunt and hard-working), how many were on her team (50), why was she asked to head the project (no one could say). Mostly, they asked what she had done in the 40 years since her discovery. After a bit of shuffling and grimacing, the answer: She had tried to find other herbs but had not succeeded.

See Separate Article ARTEMISININ AND MALARIA MEDICINES, TREATMENTS AND DRUGS factsanddetails.com

Chinese Medicine Versus Western Medicine

Western medicine was introduced to China in the 16th century by missionaries but for centuries was merely a curiosity. In the 19th century missionary hospitals became more widespread as Europeans increased their presence in China. Many Chinese refused to use them in part because of rumors that were spread about Western doctors harvesting organs from patients and storing them in churches and using children’s hearts in black magic rituals. Western medicine won some respect in 1894 during an outbreak of the bubonic plague, a disease that Chinese herbal medicine was powerless in combating.

The extent to which traditional and Western treatment methods were combined and integrated in the major hospitals varied greatly. Some hospitals and medical schools of purely traditional medicine were established. In most urban hospitals, the pattern seemed to be to establish separate departments for traditional and Western treatment. In the county hospitals, however, traditional medicine received greater emphasis. On its down side, Huh Jong, a professor at Seoul National University, wrote: "Western medicine is designed to fight diseases which have already invaded the body and to use string medication to eliminate the harmful microorganisms. However, the side effects of strong treatments can result in further deterioration to the patient’s well-being and viruses often grow immune to intensifying medication.”

Dr. Haruki Yamada of the Oriental Medicine Center of the Kitasato Institute in Tokyo said, "Western medicine is very important and efficient for the treatment of many diseases but it is not perfect. Oriental medicine can cure diseases that cannot be covered by Western medicine. Using both types can be very useful depending on the disease." The World Health Organization is currently researching Asia medical system.

Many doctors in Asia try to use the "three roads" approach to medicine: Western medicine, Oriental medicine and a combination of the two. If a Chinese man or woman becomes ill often he or she will seek out a doctor who practices Western medicine and one who practices Chinese medicine. According to one doctor, "traditional Chinese therapies are applied for better treatment and recuperation results." Still there is little evidence that Chinese medicines can be used to cure serious diseases like cancer and heart disease. Some hospitals, like 304 Military hospital in Beijing, have an east wing for Chinese medicine and a west wing for Western medicine. People with chronic ailments like arthritis and back pain are directed to the east wing. Those with acute problems like a heart attack or a broken leg told to go to the west wing.

Chinese Medicine in the West

Oriental medicines are becoming increasingly popular in the West. A third of all adult American males have seen a doctor who practices oriental medicine. Oriental medical doctors have been sent to Ethiopia, Gabon and Kazakstan to help ailing poor people.

Herbs that have been scientifically tested using Western methods and shown to fight infection, reduce inflammation or reduce fever include: 1) Licorice root, 2) Reed rhizome, 3) Burdock fruit, 4) Forsythia fruit, 5) Bamboo leaf, 6) Fermented soybean, 7) Balloon flower, 8) Honeysuckle flower, 9) Schizonepeta spike and 10) Mint leaf [Source: National Geographic, January 2019]

Peter Gwin wrote in National Geographic: “But the practice of melding the modern with the traditional is also spreading among health care consumers. When they don’t find relief from Western medicine, Americans increasingly are turning to traditional treatments, notably acupuncture, which is now covered by some health insurance plans, and cupping, a muscle therapy that involves suction and is endorsed by many professional athletes. The internet has fostered the growth in herbal remedies, which are often cheaper than doctor-prescribed pharmaceuticals. A patient can read about a traditional remedy online, order the herbs on Amazon, and watch YouTube videos on how to prepare them at home. The result is a growing alternative health sector, which in 2017 saw U.S. herbal supplement sales top eight billion dollars, a 68 percent increase since 2008. [Source: Peter Gwin, National Geographic, January 2019]

For many years the Lester Institute in Shanghai studied Chinese medical practices. Decades ago a leading drug-making firms in the United States employed a Chinese scientist for the express purpose of studying possible applications of Chinese drugs to modern pharmacy.[Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University]

Image Sources: Tqnyc; All Posters com; ; Wikipedia; Compassionate Dragon Healing; Accupuncture Products; Iron Palm Arts; WWF; Ciao Su Nature Products; South Aquaculture

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022