CONSUMER AND BUSINESS CUSTOMS IN THE DEVELOPING WORLD

market in Africa Developing world economies are very cash oriented. Cash is used for most transactions. Credit cards are not widely used. Most people don’t even have bank accounts. Money is often stashed away in a closet or under blanket or some such place. ATM machines are found only in the cities.

There are no paychecks. People get paid in cash or though a transfer to a bank, and pay their bills at banks or post offices. Outside the cities, some people are so cash poor they barter many items.

Women have traditionally controlled the family's finances. They are careful shoppers and good at finding bargains and bargaining with merchants. It is estimated that women make up 80 percent of the transactions performed in the informal economy.

Transactions at banks often involve waiting in line, filing out some papers and getting a number. After waiting for a period of time your number is called and you hand over your money and submit your papers and then wait again until your number is called again and the transaction is completed.

Most people don’t use banks because they are too poor or they don’t trust them. Personal lending is has traditionally been done informally among friends, family members and business associates. Some villagers are in debt to moneylenders. If their crops fail, they often have little choice but to borrow money but in doing so they risk losing their land.

Villagers usually have no savings and live day to day. They have little money and their purchases are often in small quantities: a bar of soap, individual cigarettes and 2-cent packets of shampoo. An ill-advised loan or medial treatment can put a family in a kind of dept that can take years or lifetime or even several lifetimes of different generation of family members to pay off.

Self-Sufficiency and Resourcefulness

Villagers have traditionally been very self sufficient, getting most of what the need from their land and animals. Things they were unable to produce themselves such as kettles, mousetraps, tools, ropes, and housing materials they purchased during occasional trips to town markets with money made from selling agriculture surpluses or animals.

Resourceful is not simply a virtue but a key to survival. A family gets ahead by taking advantage of any opportunities that comes their way. They often don't want to throw anything away and lose the opportunity to sell it or make it into something. Villagers can do a lot with a little. They can jam five people on a motorbike and get 65 people on a minibus made for 20. But for services such as building a new room on their house or digging a well help is needed and a personal contact is necessary to seek that help. If a villager can't find someone with a service he needs he has to find someone who does. Often services are battered and no money changing hands.

The economist Eduardo Lora found that in countries with similar levels of per capita income, respondents experiencing higher economic growth rates on average, said they were less happy than those with less growth. One explanation is that rapid economic growth typically brings greater instability and inequality and that makes people unhappy.

Wealth, Honor and Hedges Against Inflation

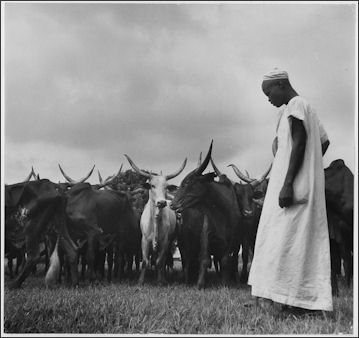

cattle has traditionally been

a sign of wealth in Africa Wealth is measured in different ways depending on the culture and living style: by the amount of land one owns, by the numbers of animals in one’s possessions, the number of people one employs, the amount of cash, gold, silver or jewelry in one’s possession, the number of carpets one owns.

Valuables such as gold, jewelry, carpets or animals are given at important life events such as births and marriages and as settlements for disputes. The valuables are give to cement social relationships and economic transactions like the transfer of a title.

Wealth is often measured in terms of money and property possessed by a clan not an individual. The greatest honor for an individual is to accept money for the clan. The sale of land is considered shameful because the clan loses influence, power and prestige if their land falls into the hands of someone outside the clan. It is particularly disgraceful to sell clan land to a foreigner.

Inflation often shapes consumer behavior. People don’t want to hang on to their cash because it quickly loses its value. They protect themselves against inflation by buying gold, foreign currency or property immediately after they get paid, which inevitably makes the inflation worse.

Underground Economy

Most people live and work outside the law in what is variously described as the informal or underground economy or the black market. They pay no or few taxes but at the same time get few benefits from the government.

The underground economy includes market sellers, moneychangers, traveling merchants, a variety of wheeler-dealers and causal worker and itinerant vendors who deal in cash. Much of the underground economy consists of service sector jobs such as plumbing, furniture sales, and home repair done on a barter basis in return for goods, other service or cash. The government doesn't like these practice because it can't collects taxes.

Government and company jobs are often low paying but are viewed as a way to gain access to benefits such as cheap housing and decent health care. Many of the material goods owned by families, such as cars, appliances and attractive clothes, are earned by working in the underground economy.

Developing the informal economy is seen by some economists as a key to providing jobs and services.

Shops and Small Business in the Developing World

shop in an Angolan village Shops have traditionally been sources of community cohesion as well as a places where people bought and sold goods. Shopkeepers chatted with customers and passed on gossip, organized festivals and were heavily involved in school and community activities.

Small shops and businesses account for a large portion of the employment and a significant portion of GNP. Many shops are two story building with the shop on the first floor and a home for the owners on the second floor.

Shoppers generally go to markets or trudge from shop to shop to buy things they need rather than go to a large supermarket. In many places, shops and street hawkers sell single cigarettes rather than packs because that is all their poor customers can afford.

Businesses that rely on door-to-door sales such as Amway, Avon, Tupperware and Mary Kay often do very well in the developing world.

Third World Markets

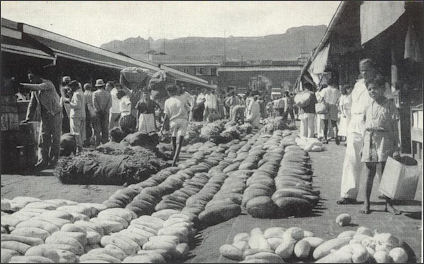

Economic life centers around markets and market day, which is usually once or twice a week. Villagers (usually women) walk or take a bus or truck to the market town with whatever they can sell — some bananas, potatoes, beans or other crop. Items are sold or bartered.

Some markets have a pretty limited selection: potatoes, corn, cassava laid out on top of blankets on the ground. Others have a wide variety of goods and are quite lively. People dress in their best clothes and show up even if they don't want to buy or sell anything. Old friends meet and catch up on the latest gossip. Crowds of people, some with bound chickens in their hands, gather around modern-day snake oil salesmen shouting into microphones plugged into small amplifiers.

On market day the road swell with people coming and going to the market. Some women walk barefoot for several hours to get to the market, even though they have shoes because they are afraid of wearing them out and want to look good when they arrive. Many buses to markets depart at two or three in the morning so that the passengers can be at the market at the crack of dawn when most of the serious buying and selling is done. By the time late-rising tourists get to the market, most villagers have long since finished shopping and they spend the rest of the day socializing.

Choosy shoppers prefers honest, straightforward sellers. Fresh food is important and animals are bought live or freshly killed. The best selection is usually in the morning and the best prices are in the afternoon when people want to get rid of what they have. Everyone knows what a fair price is but there is usually some god natured haggling before a sale is made.

Market Women, Families and Work

Markets are dominated by market women. In Africa women dominate the informal economy. According to some economists small scale trading carried out by women accounts for 30 to 50 percent of the GDP in some countries. In Kenya in the 1990s women produced 80 percent of the corn and did nearly 100 percent of the marketing for it.

Family members and neighbors often pool their resources for large purchases. Six or seven farmer often get together to buy a tractor which they then will hire out to help pay off their loan. Family members and relatives often share the cost of a car and all hell break loose if someone wrecks it.

Many men live and work in the cities and send money home to their families in their village. People who work overseas or as shopkeepers and laborers in their cities are often treated like big shots back in their home village.

See Labor

Property Rights in the Developing World

Throughout most of the developing world there is no formal system of property rights. In many cases, people who lived in a house and occupied land for decades have no legal title to the land. According to one estimate 80 percent of the people in the developed world live in places where it is impossible to identify who owns what or figure out the rules that give owners ownership.

When there are defined property rights the property is usually owned by an elite group of landowners, who have often cheated peasants out of land that should be theirs.

Many people have been forced off their land because they have no official title to it. Many people don't now how to get land titles and those that do don't have the money to bribe bureaucrats to get the job done properly.

Titling the Assets of the Poor

Titling the assets of the poor is a radical idea proposed by Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto and detailed in his book “The Mystery of Capital” to end the cycle of debt and impoverishment in the developing world.

De Soto’s main idea, which has received endorsements by people as diverse as Margaret Thatcher, Bill Bradley and Milton Friedman, is to give poor people title to the property and the land they live and work and this in turn would give them access to credit because they could put their property and land up as collateral.

Clear property rights and a legal system to back them up make it easier to attract credit, capital and investment. De Soto wrote in the New York Times: “Legally created titles and stock certificates generate investment clear property records guarantee credit; documents allow people to be identified and helped; companies can pool resources...mortgages raise money; contacts solidify commitments.”

Remittances

Remittances (the wiring of money from one place to another) has become the principal source of foreign capital in the developing world. More money is wired from people in developing countries, working overseas, to family members in their home countries than these countries receive in foreign aid or foreign investment. [Source: Foreign Policy magazine]

Most of the remittance money arrives as a few hundred dollars wired every month, enough to boost a family from abject poverty to having enough to eat, buy things they need and possibly start a business. The money is particularly important in very poor countries and is generally spent on food and clothing, education, medicines and housing. Remittances are good on a personal and development level because the money goes directly to people who need it without inference from foreign governments, aid agencies and corrupt officials.

The amount of remittances sent to developing countries rose from $17.7 billion in 1980 to $30.6 billion in 1990 to $59 billion in 1995, roughly equal to foreign aid that year, to $80 billion in 2002 to $160 billion in 2004, double the foreign aid that year. The rise is attributable to the increase in the number of migrant workers working abroad, particularly in the United States, Europe and oil-exporting Persian Gulf states.

Some of the money is wired. Some is sent using Informal Value Transfer System set up by people in home countries and where the immigrants are working. Remittances are a manifestation of the global migration of labor and the relaxing of restrictions on the international movement of money encouraged by the IMF. Some forms of remittances have come under review because some money is believed to end up in the hands of terrorist networks such Al-Qaida.

Immigrant Networks, A Spark in the World Economy

The Economist reported: “Diaspora networks — of Huguenots, Scots, Jews and many others — have always been a potent economic force, but the cheapness and ease of modern travel has made them larger and more numerous than ever before. There are now 215 million first-generation migrants around the world: that’s 3 percent of the world’s population. If they were a nation, it would be a little larger than Brazil. There are more Chinese people living outside China than there are French people in France. Some 22m Indians are scattered all over the globe. Small concentrations of ethnic and linguistic groups have always been found in surprising places — Lebanese in west Africa, Japanese in Brazil and Welsh in Patagonia, for instance — but they have been joined by newer ones, such as west Africans in southern China. [Source: The Economist, November 19, 2011]

These networks of kinship and language make it easier to do business across borders (see article). They speed the flow of information: a Chinese trader in Indonesia who spots a gap in the market for cheap umbrellas will alert his cousin in Shenzhen who knows someone who runs an umbrella factory. Kinship ties foster trust, so they can seal the deal and get the umbrellas to Jakarta before the rainy season ends. Trust matters, especially in emerging markets where the rule of law is weak. So does a knowledge of the local culture. That is why so much foreign direct investment in China still passes through the Chinese diaspora. And modern communications make these networks an even more powerful tool of business.

Diasporas also help spread ideas. Many of the emerging world’s brightest minds are educated at Western universities. An increasing number go home, taking with them both knowledge and contacts. Indian computer scientists in Bangalore bounce ideas constantly off their Indian friends in Silicon Valley. China’s technology industry is dominated by “sea turtles” (Chinese who have lived abroad and returned).

Diasporas spread money, too. Migrants into rich countries not only send cash to their families; they also help companies in their host country operate in their home country. A Harvard Business School study shows that American companies that employ lots of ethnic Chinese people find it much easier to set up in China without a joint venture with a local firm.

Rich countries are thus likely to benefit from looser immigration policy; and fears that poor countries will suffer as a result of a “brain drain” are overblown. The prospect of working abroad spurs more people to acquire valuable skills, and not all subsequently emigrate. Skilled migrants send money home, and they often return to set up new businesses. One study found that unless they lose more than 20 percent of their university graduates, the brain drain makes poor countries richer.

Government as well as business gains from the spread of ideas through diasporas. Foreign-educated Indians, including the prime minister, Manmohan Singh (Oxford and Cambridge) and his sidekick Montek Ahluwalia (Oxford), played a big role in bringing economic reform to India in the early 1990s. Some 500,000 Chinese people have studied abroad and returned, mostly in the past decade; they dominate the think-tanks that advise the government, and are moving up the ranks of the Communist Party. Cheng Li of the Brookings Institution, an American think-tank, predicts that they will be 15-17 percent of its Central Committee next year, up from 6 percent in 2002. Few sea turtles call openly for democracy. But they have seen how it works in practice, and they know that many countries that practise it are richer, cleaner and more stable than China.

As for the old world, its desire to close its borders is understandable but dangerous. Migration brings youth to ageing countries, and allows ideas to circulate in millions of mobile minds. That is good both for those who arrive with suitcases and dreams and for those who should welcome them.

Credit Cards

Credit cards are becoming more common place in developing countries likes China, India, Turkey and Brazil. In Asia, Latin America and central Europe credit card transaction volume is rising by 20 to 30 percent a year

Credit card companies make their money by collecting a fee on each card and small percentages from sellers on purchases. Banks are the ones that make their money by charging interest for loans and late fees.

In middle-income developing countries credit cards are often given out with a minimum of fuss in shopping malls, factories and university campuses, The people that acquire them are sometimes relatively unsophisticated shoppers. Sometimes they go on shopping sprees and quickly build up crunching debt that they find difficult to pay off.

In many ways credit cards hasten development, They provide a means for people to buy motorbikes, refrigerators and stereos. By keeping a tally of transactions they also help shrink the size of the black market and allow governments to collect taxes they might otherwise miss.

Western Products

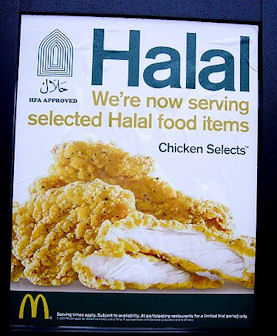

Halal McDonald's Nike, MTV, Disney and McDonald’s, are as well-known in the developing world as they are in the developed world. Shops in remote villages that often don't have milk, cheese, or butter always seem to have plenty of Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Orange Crush plus calenders and posters produced by these companies. Coke or Pepsi truck are sometimes among the few vehicles you see on the roads in remote areas. In some mountainous areas you see people carry basketfuls of Coke and Pepsi bottles on their backs on footpaths and trails.

McDonald’s, Kentucky Fried Chicken and Pizza Hut are franchises that are locally owned. Coke, Fanta and Pepsi are made by local bottlers. They provide badly needed jobs for the people and taxes for the government.

Unilever has been very successful marketing products like shampoo in small packets in the developing world. Nestle sells instant milk and baby formula.

General Electric is aiming to become a one-stop general store for developing world infrastructure, offering a wide range of things including jet engines, health care equipment, turbines, rail products, water oil and gas equipment, and even financial services. G.E. is taking this route in part because it sees more growth potential in the developing world than it does in the developed world and aims to create good relations with the countries it does business with by employing local people by doing things like shipping parts for locomotives and having them assembled locally.

Shoe manufacturers and textiles makers that rely on cheap labor are among the first industries to arrive. They mainly produce goods to be exported back to the country where the company is from or for the world market. These companies raise wages and living standards. While they have been accused of exploiting labor and damaging the environment in the United States and Europe they are welcome in emerging economies as engines for growth.

A study of Oxfam found that multinational retailers and grocery chains in their quest for ever lower prices for customers are driving down wages and lengthening work hours for millions of workers, the vast majority of them women.

Business in the Developing World

Pineapple vendors For the average person, a market economy has meant that people could sell anything they wanted on the streets and families could pool their money together to buy a minibus and start their own transportation service. Talented managers in local companies often can not attain high positions because they are held by family members of the owners.

Shops have traditionally been sources of community cohesion as well as a places where people bought and sold goods. Shopkeepers chatted with customers and passed on gossip, organized festivals and were heavily involved in school and community activities.

Small shops and businesses account for a large portion of the employment and a significant portion of GNP. Many shops are two story building with the shop on the first floor and a home for the owners on the second floor.

Shoppers generally go to markets or trudge from shop to shop to buy things they need rather than go to a large supermarket. In many places, shops and street hawkers sell single cigarettes rather than packs because that is all their poor customers can afford.

Businesses that rely on door-to-door sales such as Amway, Avon, Tupperware and Mary Kay often do very well in the developing world.

Advertising on television and radio often doesn't reach small villages, companies like Colgate-Palmolive rely on giving out free samples from vans with their logo painted all over it that travel from village to village.

An increasing number of large international corporations are making products geared for the developing world. They include 1) Unilever, which sells small packets of detergent and shampoo; 2) Royal Philips Electronics, which sells cooking stoves at very low prices; 3) Vodafone, which offers remittance services via cell phones for migrant workers; 4) Sumitomo Chemical, which locally produces and sells mosquito nets; and5) Yamaha Motor, which sells water purifiers to rural villages.

See Separate Article GRAMEEN BANK AND MICROFINANCE factsanddetails.com

Tourism in the Developing World

.jpg)

train in Peru Tourism is a huge labor intensive industry that generates lots of jobs and has a large multiplier effect. Not only does it create jobs for people working in the tourist industry itself but it also produces jobs in construction, transportation, agriculture, craft production, fishing and livestock raising.

Tourism is a fickle industry affected by local, regional and world economic and political conditions. In 2003, tourism around the globe was affected by the Iraq war and the SARS scare. Many places that nothing to do these problems and were in different continents were hurt.

Villagers rarely see foreigners. If they do see one, they are a source of endless fascination and villagers will stare and stare and stare. It is not uncommon for crowds of a hundred people to gather around strangers and tourists.

Children often come up to tourists, clamoring for candy, money or pens. Sometimes a mob scene develops when a tourist actually gives out something and everyone kid want one. Sometimes the children get hostile and throw stones.

Some criticize tourism as a destabilizing force. Journalist Chris Stager wrote, "A begging child might bring home in one day what a parent makes in a month. Incentive to work fades. And so does parental authority."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012