GRAMEEN BANK AND MICROFINANCE

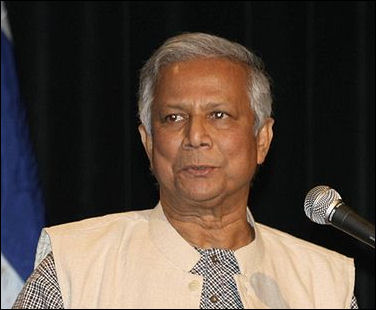

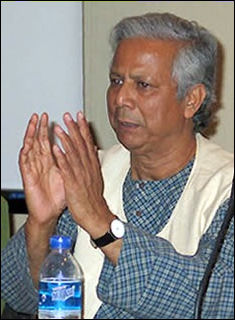

Muhammad Yunus The Grameen Bank in Bangladesh pioneered the idea of giving out micro-loans between $27 and $500 to poor people so they can start or expand small businesses such a street vending operations, cell telephone rentals or small cottage industries to pull themselves out of poverty. If loans are paid back borrowers qualify for larger loans.

The Grameen Bank has received worldwide attention for providing loans to ultra-poor women to start up "micro-enterprises." It’s founder Muhammad Yunus has been praised at home and abroad by politicians and financiers as the "banker to the poor." "Grameen" is the Bangla (Bengali ) word for "Village” or “Rural.” Advocates for microfinance say the concept and system it has achieved much. They say that extending credit to the poor has fostered small businesses, helped promote gender equality, lifted incomes, and improved access to food and education for some of the world's most desperate citizens.

Microfinance has excelled at getting a lot of money to a lot of borrowers quickly, disrupting established networks of power and patronage in the process. In 2009, more than 128 million of the world's poorest families took microloans - up from just 7.6 million in 1997 - and investment funds for microfinance totaled over $11 billion, according to a Microcredit Summit Campaign. [Source: Erika Kinetz, AP, March 7, 2011]

Jacques Attali wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “Grameen Bank is unmatched in the world of traditional banks. Its workers care tremendously about helping the poor, all spending nearly a year living among the population they are going to serve. With the organization being so intimately associated with the precepts of its founder, the leadership transition has to be handled with great care.” [Source: Jacques Attali, Christian Science Monitor, April 11, 2011]

Bangladesh’s government owns 25 percent of Grameen while customers hold the balance. It lends to its 8.35 million clients, of which 97 percent are women and more than 112,000 beggars, using funds from its deposits. The bank employs 26,000 people and has 2,565 branches across the South Asian nation, where the Asian Development Bank estimates almost half the population of 144 million lives on less than $1.25 a day. Grameen has lent $10.3 billion since it began operations in 1976 and had a loan recovery rate of 97 percent as of the end of February, according to the lender’s website. [Source: Arun Devnath, Bloomberg, May 12, 2011]

Book: “The Price of a Dream: The Story of the Grameen Bank and the Idea That is Helping the Poor to Change Their Lives” by David Bornstein (1998, Simon & Schuster).

Mohammed Yunus and Early History of the Grameen Bank

The Grameen Bank was founded by Mohammed Yunus, a Bangladeshi economic professor. Yunas was born in 1940 in Chittagong. He attended Chittagong University in Bangladesh and received a Ph.D. from Vanderbilt University. During his stay in the United States in the 1960s he was influenced and inspired by the idealism, civil rights movement, and student activism he saw and experienced. He embraced Martin Luther King as a hero. Yunus has said that his most powerful memory from his youth was leaving South Asia to attend a Boy Scouts World Jamboree.

Yunus returned to Bangladesh in 1971 after it became independent and took a position at Chittagong University, where he encouraged students to close their books and study village life. After the great flood and famine in Bangladesh in 1975 Yunus began visiting villages near Chittagong.

Yunus reportedly got the for Grameen idea one afternoon in 1976. He took a walk to a village a mile or so away from Chittagong University, where was head of the department by that time, and he ran into an old woman selling bamboo stools who said she made only two cents a day from her business. When Yunus asked her why he made so little. The woman told Yunus she needed loans to buy materials and said the person who lent her money was the same person who bought her final product. The buyer bought her stools at an artificially low price, keeping the woman perpetually in debt, in a kind of village version of indentured servitude. . Yunus gave the woman and 47 other villagers loans of $27. All of them paid him back.

Yunus and his students did surveys in other villages and found that villagers had virtually no capital to invest in their business and were thus easily manipulated by moneylenders and middlemen who bought their products. Yunus initially gave out the loans in one village from a tea stall. Over time the system evolved into micro-financing.

History of the Grameen Bank

Grameen headquarters Convinced that large scale development projects favored by the United States and the Soviet Union did little to help ordinary poor people, Yunas began arguing that that development money could better spen than it was giving loans for people to use in the informal economy. Yunas outlined the Grameen Bank scheme in his book “Give Them Credit” (1970s). Yunas pitched his idea to the Bangladesh government. Officials scoffed a his idea of lending money to the poor without collateral. Unable to get support Yunus decided to act as the guarantor for people who took out loans in 100 or so villages. Everyone paid him back.

The Grameen bank was unofficially founded in 1977. In 1978, Yunus and some of his graduate students opened up the first branches of the BANK. The bank expanded by operating from special windows in conventional banks.

In 1983 Yunus formally founded the Grameen bank. In that year the bank became a separate entity, with 86 branches, 58,000 clients and support from the United Nations, the Ford Foundation and the Bangladesh Bank. As time went the bank grew very quickly and received international attention. By 1988, it had 501 branches and 490,000 borrowers.

Describing the Grameen Bank headquarters in Dhaka in the mid 1990s, David Bornstein wrote in Atlantic Monthly, the office has "no receptionist, no carpets, no elevators, and few telephones. The rooms are equipped with ceiling fans, manual typewriters, paperweights and stacks of ledgers. Only the computer room on the fifth floor has air conditioning."

As of 1998, the Grameen Bank had 1,050 branches and had loaned more than $2 billion. It employed 10,000 university and high school graduates scattered throughout the country. By 2000 Grameen had given out loans to 2.4 million borrowers, mostly women, in 39,000 villages. As of 2001, the bank had given out $3 billion worth of loans in Bangladesh.

In 1986, Bill Clinton, then governor of Arkansas, invited Yunus to the United States. Clinton wanted to establish a similar banking system in Arkansas. The two men became friends. Over the years Yunus has won a number of awards including 1993 CARE Humanitarian Award for Development and the 1994 World Food Prize.

Philosophy of the Grameen Bank and Skepticism Of Its Success

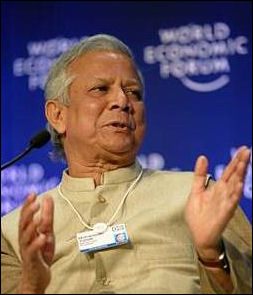

Yunus at the World Economic Forum

2009 Annual Meeting The philosophy of the Grameen Bank is simple: that the widespread availability of credit can solve many problems in undeveloped areas and that individuals in the undeveloped areas often have the best ideas and the most efficient means to develop them.

The objective of Grameen-style programs is to get local people to run businesses and keep them going after the aid agencies have left. Grameen Bank proverb is: "If you give a man a fish you feed him for a day. If you teach him to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.” Another objective of Grameen-style program is to improve the status of women and help them start businesses so they delay having children and don't contribute to overpopulation.

Yunas told Atlantic Monthly, "You look at the tiniest village, and the tiniest person in that village, a very capable person, a very intelligent person. You only have to create the proper environment to support these people so that they can change their lives."

Before the Grameen Bank came along villagers were forced to borrow money from moneylenders who charge such high interest rates (10 to 20 percent a week) that all the profits a villager makes ends up going to the moneylender, This means villagers have no money to get ahead or improve their her businesses. Yunus has called the moneylender trap "a form of bonded labor."

Yunas developed three main criteria for borrowers: 1) the loans had to be repaid on time: 2) only the poorest, landless villagers were eligible ;and 3) most of the money would be lent to women."

Erika Kinetz wrote in AP in 2011, “Evaluations which benchmark results against control groups so far haven't found evidence that microloans alone are enough to solve the complex problems of the deeply poor. Still, many warn that a world without microfinance would be much worse off.” [Source: Erika Kinetz, AP, March 7, 2011]

"Microcredit is a good thing but has been oversold," said Yale professor Dean Karlan, who authored one such study. "It will not raise people out of poverty, certainly not single-handedly. But there are benefits that are important."

Grameen Bank and Women

Village women of Bangladesh Most of the Grameen loans are given to women (94 percent at one point). There are several reasons for this. Women are better at repaying the loans then men, who often squander their money on risky deals, drink or gambling. Because they are usually responsible for raising the family and keeping track of the family finances women generally put their money into things that benefit the entire family and don't waste it. Before the women receive the loans they are often given lectures on the importance of repayments. Many of the women who receive loans pull their families out of poverty in five years or less.

Yunus told Newsweek, "Initially we tried to find equal numbers of men and women borrowers...Then we realized than many positive things could be achieved by lending to women because when a woman's income increases, the immediate beneficiaries are the children. A woman looks to the future with a planned strategy to improve the family situation. Men don't pay attention to such things. Since women performed better in bringing changes to the family, we decided to give priority to women."

As for the husband of women borrowers Yunas said "At first...men ere angry with their wives for handling money. We tried to show them that it is good if the wife contributes to the family income: that way the family could move out of poverty faster...So that the husband does not feel humiliated that his wife gets the money, we have [counseling] sessions with him and encourage the wife to discuss things with him so he doesn't feel left out.”

Grameen Bank also pursued a social agenda with its women borrowers, After many women receive their money they recite the following pledge: "We shall plan to keep our families small. We shall keep free from the curse of dowry. We shall not practice child marriage." In Bangladesh twice as many Grameen bank women use contraceptives as the national average.

Grameen Bank Loans

Grameen loans vary from $60 to $280 and average about $180. They are typically paid back in one year in fifty equal installments. Despite interest rates as high as 20 percent, the bank claims a 97 percent repayment rate, a rate comparable to Chase Manhattan. They achieve this even though the borrowers have no or little property and can't offer anything as collateral.

One reason for the bank’s success is its system of self-regulation, Everyone who takes out a loan becomes a member of a five-person borrowing group, a 40-member center and attend meetings every week. Groups share responsibility for the loan repayments and defaults.

If one member of the group fails to pay the entire group loses their loan. This means that members are careful to pick new members who, without fail, will pay back their loans. If all five members repay their loan quickly they are guaranteed access to credit for the rest of their lives,

Loan programs run by aid agencies have not been as effective as those run strictly like a bank. While the Grameen bank’s interest rates — often 25 percent or more — may seem high they are infinitely better than rates of up to 1,000 percent charged by local moneylenders and loan sharks.

Microfinancing and Businesses Started with Grameen Bank Loans

Fruit Stand in Egypt Borrowers have used Grameen loan money to start home-based bamboo weaving businesses, repair radios, buy weaver's looms, pay for seeds and fertilizer, process mustard oil, buy dairy cows, cultivate jackfruits, sell cookware door to door, trade brass, sell popsicles, build silkworm sheds, husk rice, starting sewing businesses, sell cosmetics from village to village, sell milk from cows, and sell medicines to neighbors and friends.

Many women bought Nokia cellular phones with their loans. By selling calls at about 10 cents a minute they can make about $2.00 a day ($700 a year) in profit and pay back the loan in three years. Rwanda’s agriculture minister Agnes Kalibata, , who has helped set up micro-financing for female farmers and given them access to markets and co-operatives,

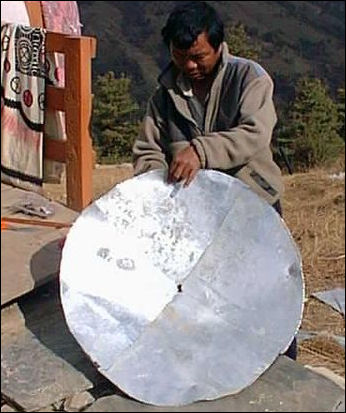

Micro-financing bodies are playing a key role in setting up alternative energy sources in villages. Praddep Dadhich of the energy research institute TERU told Reuters, “They are reaching people who otherwise have limited or no access to electricity and depend on kerosene, diesel or firewood for their energy needs...The applications not only satisfy these needs, they also improve the quality of life and reduce the carbon footprint.”

Grameen Phones

Cell phones were one of the moving forces behind the Nobel-prize-winning Grameen micro-financing system. In Bangladesh, Grameenphone covers 98 percent of the country and serves the majority of the country’s cell phone users. Phones developed for the developing world sell for as little as $20 a piece.

GrameenPhone Ltd was started in 1996 in Bangladesh with the help of a Norwegian telephone company after a Bangladeshi expat living in the U.S. named Iqbal Quadir posed a question to Grameen founder Muhammed Yunus: if you can give a micro-loan to a woman to buy a cow why can’t you give her one to invest in a phone. The company focused on two sectors: 1) urban customers and 2) village phone schemes in which people — mostly village women — took out small loans to purchase cell phones and they in turn sold time on cell phones to others.

GrameenPhone Ltd made a pre-tax profit of $27 million after only five years in business and attracted nearly $200 million in investment as of 2002. By the mid 2000s, the system employed 250,000 “phones ladies”, who used microcredit loans to buy specially-designed cell phone kits costing about $150 outfit with special long-lasting batteries. The ladies often operate in villages as phone operators who charge a small commission to make and receive calls. By the late 2000s, GrameemPhone was pulling in annual revenues of $1 billion a year.

Similar systems have been set up in Indonesia, Rwanda, Uganda, Cameroon and other countries. Quadir, who is now at MIT, told the New York Times magazine, “Poor countries are poor because they are wasting their resources. One resource is time, another is opportunity. Lets say you can walk over to five people who live in your immediate vicinity, that’s one thing. But if you’re connected to one million people, your possibilities are endless.”

Profits and Benefits from Grameen Bank Loans

making a satellite dish in Nepal The loans can make the difference between scrounging for a single meal and having three square meals. With their profits, some women have been able to send their daughters to university. Some people have earned enough money to buy land. One bank director told Reuters. “Our main success is that we have been able to bring the women in poor families out of the hot fields, put them in gainful work and infuse some hope in their lives.”

The Grameen Bank also helps villagers to acquire loans to buy medicine, pay for their children's education and build houses, They are also involved in setting up village-based health-care, pension and insurance systems.

The Grameen Bank make a profit but some regarded the profits as not "real" because Grameen receives funding at low rates from international aid groups and the Bank of Bangladesh. Starting in the 1990s Grameen began borrowing money at interest rates paid by normal companies and was issued bonds.

Grameen kept going after the 1991 cyclone-flood. It suffered in 1998 when a long-term flood ruined the businesses of many people and made them unable to pay back their loans. At that time Grameen was forced to borrow $100 millon from the World Bank to stay afloat.

Influence of the Grameen Bank and Growth of Microfinancing

Grameen Bank has launched a revolution in the approach towards development and provided a model for "microcredit" programs all over the Third World. By 2001 the Grameen bank idea had spawned 7,000 similar banks.

Peace Corps workers have set up credit unions which start with one farmer being given crop and fertilizer loans. If the loan is paid back, other villagers get loans. The idea is that peer pressure will help prevent the farmer from squandering his money on something other than seed and fertilizer.

More and more large banks, pension funds and private equity firms are getting into micro financing and are investing billions of dollars in it. People in the development field welcome the money, increased competition and new financial services offered but also worry that the trend will put profits ahead of helping the poor and exploit the poor and put them in debt.

Erika Kinetz wrote in AP in 2011, In India, Government lending programs for the poor in India have been losing ground to microfinance groups. In 2007, state-backed self-help groups, which link local borrowers with banks, sometimes at subsidized interest rates, added 8.5 million clients, while microfinance groups added 3.2 million. Two years later, self-help groups added just 6.7 million clients, while microfinance groups added 8.5 million, according to M-CRIL, an Indian micro-credit rating agency.

Problems for Grameen Bank and Microfinancing

market women in Africa Erika Kinetz wrote in AP in 2011, “Long heralded as a way to lift the downtrodden out of poverty, microfinance is under a cloud. The stories of lives being changed by a $27 microloan and picture perfect scenes of smiling women with colorful handlooms, empowered by affordable credit, have been replaced by headlines about borrowers driven to suicide. At best, microfinance seems to be failing to achieve its most noble goal: poverty alleviation. At worst, some lenders are contributing to a cycle of indebtedness and abuse, just like the loan sharks they sought to replace.” [Source: Erika Kinetz, AP, March 7, 2011]

Officials in Andhra Pradesh are preparing to prosecute 51 cases of suicide allegedly linked to coercive microfinance groups. Meanwhile the central bank is considering new regulations which would, among other things, cap microfinance interest rates. "Irresponsible lending leading to multiple loans without due diligence, unproductive loans for consumption and consumer durables, lack of transparency in operations, usurious interest rates, coercive recovery practices, have all resulted in hyper-profits to microfinance institutions and impoverishment of the poor," R. Subrahmanyam, Principal Secretary of Rural Development in Andhra Pradesh, told AP.

Critics say the industry has grown too quickly for its own good, with too much rapaciousness and too little regulation. That has fostered a breakdown in lending discipline, with multiple loans to overextended borrowers, and allowed some unscrupulous players to thrive.The controversy has hit the heartland of microfinance in South Asia hard. As India prepares charges in 51 cases of suicide allegedly linked to coercive microfinance institutions, microfinance's founding father, Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, is fighting to hold onto his position as head of Grameen Bank in a Bangladeshi court.

Crackdowns on Microfinance

Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, In November 2010 “Andhra Pradesh, one of India’s most populous states, cracked down heavily on private microfinance institutions (PMFIs), banning many of their activities and telling borrowers they did not need to repay their loans. State authorities said they were prompted to take decisive action by a spate of suicides by borrowers who were unable to pay their debts. Roughly 80 clients were reported to have taken their own lives last year — an alarming figure, though tiny relative to the 26.7 million active borrowers from PMFIs in India. [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, March 7, 2011, Shashi Tharoor, a former Indian Minister of State for External Affairs and UN Under- Secretary General, is a member of India’s parliament]

Salt farmers in Africa Andhra Pradesh officials charged that PMFIs, which had lent around 80 billion rupees (nearly $2 billion) in the state, levy “usurious” interest rates (24-30 percent per year) to sustain their promoters’ extravagant salaries and profits. In addition, too many borrowers had taken multiple loans from different sources and were unable to repay them. Aggressive agents were marketing the loans with no heed to borrowers’ capacity to repay. It was alleged, too, that coercion was being used to exact repayment, leaving victims with no way out but to end their own lives.

One institution that received unwelcome attention was SKS Microfinance, once a poster child for the PMFIs, which had done so well and grown so large that its initial public offering last year was oversubscribed 13-fold and raised $350 million. The salaries paid to its top executives — as a reward, essentially, for lending successfully to the poorest of the poor — were excoriated by leaders across India’s political spectrum. SKS’ Chairman, Vikram Akula, reportedly made $13 million by selling some of his shares last year. Is it moral, critics asked, to profit so much from providing services that alleviate poverty?

Defenders of Microfinancing Blame a Few Bad Apples and Vested Political Interests

Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “But the counter-argument is that professionally-run private microcredit is better than no credit at all — the situation most of the poor confront. State banks are supposed to lend generously to India’s rural poor, but their operations are mired in inefficiency and corruption. Loans often require bribes, and the banks’ procedures are bewildering to the unlettered. Traditional moneylenders are the only alternative, and they extort far more than 30 percent a year — often at the point of a knife, or worse.” [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, March 7, 2011]

"To stifle an entire industry is wrong," said Vikram Akula, chief executive of SKS Microfinance, whose listing on India's stock market last year sparked fierce debate about how much profit is justifiable when helping the poor. "It is the poor who will ultimately suffer the most if they have to return to village loan sharks for financial services." [Source: Erika Kinetz, AP, March 7, 2011]

Some say that the remarkable growth and success of microfinancing prompted a backlash from vested political interests. "The poor is a constituency politicians see as their own turf," said Alok Prasad, chief executive of India's Microfinance Institutions Network, whose 46 members represent about 85 percent of the lending in the sector in India. "Anything which leads to greater empowerment of the poor makes them insecure."

Erika Kinetz wrote in AP in 2011, “In India, some say pandering for voters, corruption and competition with a state-backed lending program helped spark a crackdown that has essentially frozen microlending in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh, India's most important microfinance market. The central bank had to step in to try and prevent microfinance institutions from going bankrupt.

Yunus at Davos

M-CRIL director Alok Misra said the gains by the private microfinance groups have shamed the government and unsettled politicians who believe the self-help groups are an important means of securing votes. "It is showing the government its own inadequacy," Misra said. "That's a big challenge for the politicians. Politicians feel poverty-lending should be in the government's name." R. Subrahmanyam,Principal Secretary of Rural Development in Andhra Pradesh dismisses charges of politicking as "a figment of the imagination of disgruntled elements." "How can microfinance institutions step on political interests?" he said. "If poor are getting exploited and commit suicides by dozens, should government be a mute spectator?"

Many within the industry would agree with that assessment and welcome better regulation. The Microfinance Institutions Network has launched a microcredit bureau in India, which should help reduce the problem of borrowers taking on too many loans.The Microcredit Summit Campaign announced a new initiative to reward groups that do more to fight poverty - a goal that has proven maddeningly elusive.

Jacques Attali wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “I personally know Muhammad very well...What has most impressed me about him is that he has never said he knows the answers. He has always experimented and adapted his organization to the needs and opportunities on the ground. Though he might have sometimes overestimated the direct impact of microfinance, he never closed his eyes to the concerns that were raised on the path he followed, particularly that some in his own organization might start to think more about profitability than poverty. For that reason, he has been one of the primary advocates of intelligent microfinance regulation, which is essential in order to permit this industry to fulfill all its promises.

Larger Questions About Microfinancing and How It Compares with Banks in the Developing World

Yunus with Barack Obama Jacques Attali wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “After a golden age of expansion, the field of microfinance has become a mature sector of the global economy. To be sure, it still has to face some very legitimate questions about profitability, interest rates, over-indebtedness and the ability to generate real economic activity beyond subsistence.” [Source: Jacques Attali, Christian Science Monitor, April 11, 2011]

Shashi Tharoor wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, The problems with microcredit raise a larger question: should the poor be served by modern financial institutions that raise their funds in capital markets, or must they rely exclusively on non-profit sources of support? The late Indian management guru C.K. Prahalad suggested in his bestselling book The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid that businesses could make healthy profits by serving the poor — and so satisfy their shareholders while promoting social development. [Source: Shashi Tharoor, Project Syndicate, March 7, 2011]

Selling five-rupee sachets of shampoo to poor consumers is considered clever marketing, but lending 5,000 rupees to a starving peasant at high interest rates is viewed as exploitative. Both activities, after all, are financed by investors looking for returns on their capital and motivated more by profit than compassion. But one is clearly less socially acceptable than the other. A high salary earned by a cosmetics or soft-drink manufacturer attracts no attention; one paid to the CEO of a company that thrives on lending to the poor appears unseemly, if not immoral.

Yet PMFIs had succeeded by meeting a genuine need. Only 50 of India’s roughly 1,000 microfinance institutions are private (as opposed to NGOs), but the top four PMFIs account for 80 percent of the market. Many of them doubled their revenues in the 2009-2010 fiscal year, reaching more than 100 million borrowers, whereas rural co-operatives, which also make small loans, grew by 3 percent, to 45 million borrowers. State banks are farther behind.

PMFIs are lending in a market vitiated by a populist political culture. Whereas microcredit institutions’ business model depends on a very high repayment rate (often exceeding 98 percent), government-run banks and state-supported co-operatives tend eventually to write off their loans when elections come around, with state and national governments waiving poor farmers’ debts for political reasons. Private institutions obviously cannot afford to do that.

There are other complications. The village moneylender, though often a shark, at least belongs to the community and knows his clients. A PMFI, as a faceless institution, relies on good faith and peer pressure to recover its money. The moneylender is happy to lend for any purpose, including non-productive expenditures like weddings and dowries, whereas a PMFI, if it is to succeed, can finance only income-generating, economically sustainable activities. But PMFIs seeking to attract private-equity capital emphasized growth over sustainability, lent indiscriminately to people who couldn’t pay them back — and attracted public opprobrium in the process.

Indian regulators are sorting out the tangle of issues that have plunged India’s microfinance industry into crisis. Ironically, none of these problems seems to have befallen Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank, which survives largely on donor grants and sustainable repayments. Yunus’s ouster, it is suggested, has much more to do with his having once expressed political ambitions. But association with a suddenly tarnished industry cannot have helped.

Problems for Mohammed Yunus

In May 2011, Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus resigned as managing director of Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank after the nation’s Supreme Court dismissed his appeal to remain as head of the microlender he founded. The government of Bangladesh, which had tried to retire Yunus on grounds of age (he was 70 in 2011 and the official retirement age in Bangladesh is 60) finally fired him from his own board. Yunus took the matter to court and eventually lost. [Source: Arun Devnath, Bloomberg, May 12, 2011]

Yunus’s exit is largely seen as a manifestation of Bangladesh’s complicated politics. In Bangladesh, the government order dismissing Yunus is widely seen as retribution for his 2007 attempt to form his own political party. Yunus has himself been frequently critical of the commercialization of microfinance.

Jacques Attali wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “For years the government of Bangladesh has argued against high interest rates — which are part and parcel of the microfinance system because they permit it to cover intense administrative costs and to develop sustainably — as a way to bring down Professor Yunus. Recently, an excuse was served on a silver platter to government officials. [Source: Jacques Attali, Christian Science Monitor, April 11, 2011]

Tensions between Yunus and the Bangladesh government grew to a critical level in December 2010 when a Norwegian television documentary accused Yunus of improperly diverting $96 million in funds in 1996 that had been donated by the country’s aid agency. Grameen denied any wrongdoing but Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina used the opportunity of the documentary to assert that Yunus treated the Grameen Bank as his “personal property” and was “spent years sucking blood from the poor.” Later the Norwegian government said there was no indication Grameen ever engaged in corruption or embezzlement.

Deputy Managing Director Nurjahan Begum took over from Yunus until Grameen’s board named a new a chief. Analysts said Grameen Bank could probably withstand the departure of Muhammad Yunus. The 25,000-employee institution is strong and well managed.

Defender of Muhammad of Yunus

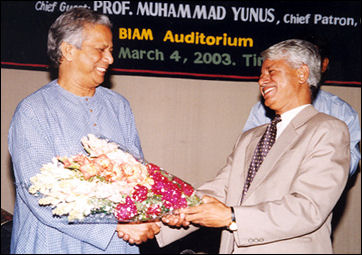

M Shahjahan, acting head of Gameen Jacques Attali wrote in the Christian Science Monitor, “Rarely does a man in the mold of Muhammad Yunus come along who has devoted his life to the least fortunate among us. Instead of living the peaceful and comfortable life he could have had, he chose to engage in a crusade against poverty through the use of micocredit that has succeeded far beyond any expectations... Political decisions should never be motivated by personal conflicts, especially when dealing with global poverty. The Bangladeshi government’s treatment of Muhammad Yunus is shameful. It does nothing to help so many who are so desperately poor in his own country. [Source: Jacques Attali, Christian Science Monitor, April 11, 2011]

The Nobel Peace Prize he received in 2006 -- along with the organization he founded back in 1983 -- symbolizes for millions of people today the best chance to create “a world without poverty.” Starting from an experiment led in the village of Jobra, Yunus worked day and night, helped by a team of dedicated associates, to patiently and progressively build up the Grameen Bank. Today it is the largest and most famous organization dedicated to microfinance in the world. Its 8.4 million active borrowers -- of which 96 percent are women villagers -- received more than $1 billion in loans during the year 2010.

Grameen Bank has become the flagship enterprise of an industry that in 2009 enabled 190 million poor families all around the world to access financial services. Even as he tirelessly pushed forward this remarkable revolution on behalf of the world’s poor, Yunus has encountered difficulties in dealing with his own government, which eventually fired him.

The fact that the Norwegian government has said there was no indication Grameen ever engaged in corruption or embezzlement apparently was not taken into account in the Bangladeshi government’s action. Nor did it take into account the fact that before the Nobel Committee decided to award the Peace Prize to Professor Yunus and Grameen Bank in 2006, it had thoroughly vetted them and found nothing to question their integrity. (A later study by David Bergman showed the allegations in the documentary were untrue).

Professor Yunus himself had expressed his intent to retire on many occasions and hand over his responsibility to a competent person who can maintain the confidence of the millions of members who own the bank. But he has more than the right to say a word in this matter. The notion that he could be simply replaced is irresponsible, since such a sudden break risks undermining confidence among employees, savers and borrowers alike, perhaps even triggering a run on savings and loan defaults. If the impression is left that political manipulations are taking over, the repercussions would be irreversible and could jeopardize the bank’s future.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012