GLADIATOR CONTESTS

Gladiator contests were the most popular sporting events in ancient Rome. They were not for the faint hearted and from the best we can figure out they were as bloody and violent as they have been made out to be. Based on analysis of the number of gladiators who fought in single events, it has been estimated that each gladiator contest lasted 10 to 15 minutes. Experimental matches staged by scholars seemed to confirm this: long matches were simply too exhausting. Dutch historian Fik Meijer has estimated that most gladiators fought two or three times a year and died between the age of 20 and 30 with 5 to 34 fights to their names.

The scale of some of the government-sponsored shows reached astounding proportions. A fragment of the Fasti Ostienses which covers the period extending from the end of March, 108 A.D., through April, 113 A.D mentions mentions two minor shows, one of 350 pairs of gladiators, the other of 202, while the major event was a government-sponsored show lasting 117 days in which 4,941 pairs of gladiators took part. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

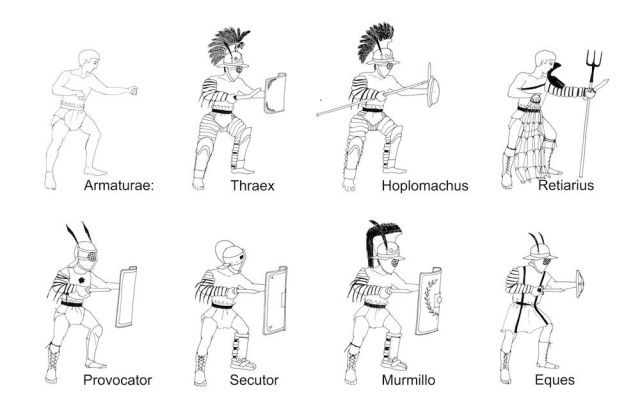

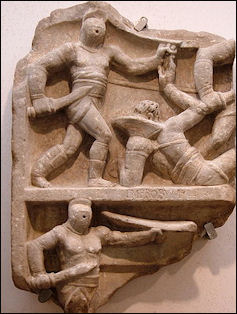

Gladiators generally fought one on one. Soldiers and gladiators wore richly decorated helmets, but the gladiators’ provided more protection for the face, making them heavier and limiting vision and hearing. Armguards made of textiles often were covered with metal plates or scales for added protection. Many gladiators wore greaves to protect their legs. The length varied, depending on the size of their shield. Nets more than six feet tall protected spectators from the action in the arena. [Source: Fernando G. Baptista, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

Jamie Frater wrote for Listverse: “Contrary to popular belief, the emperor did not give a thumbs up or down for a gladiator as a signal to kill his enemy. The emperor (and only the emperor) would give an open or closed hand – if his palm was flat, it meant “spare his life”, if it was closed, it meant “kill him”. If a gladiator killed his opponent before the emperor gave his permission, the gladiator would be put on trial for murder, as only the emperor had the right to condemn a man to death. [Source: Jamie Frater, Listverse, May 5, 2008]

RELATED ARTICLES:

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: THEIR LIVES, DIETS, HOMES AND GLORY europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR SCHOOLS AND TRAINING europe.factsanddetails.com

FAMOUS GLADIATORS europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: LAYOUT, ARCHITECTURE europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007); Meijer is a professor of ancient history at the University of Amsterdam. The book is interesting and is good at anticipating questions readers have and providing satisfactory answers on topics like the events and weapons in the contests and how the gladiators were paid and fed. Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome” by Roger Dunkle Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

Film “Gladiator”, with Russel Crowe, directed by Ridley Scott (2000) DVD Amazon.com;

“The Way of the Gladiator: Inspiration for the Gladiator Films” by Daniel P. Mannix (2024) Amazon.com;

“The Real Gladiator: The True Story of Maximus Decimus Meridius” by Tony Sullivan (2022) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: 100 BC–AD 200" by Stephen Wisdom, Angus McBride (Illustrator) (2001) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators 1st–5th centuries AD” by François Gilbert, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator), (2024) Amazon.com;

“Gladiators: Deadly Arena Sports of Ancient Rome” by Christopher Epplett (2017) Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiator: The Secret History Of Rome's Warrior Slaves” by Alan Baker Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Slavery in the Roman World” by Sandra R. Joshel (2010) Amazon.com;

“Slavery and Society at Rome” by Keith Bradley (1994) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” by Howard Fast (1951) Amazon.com;

“Spartacus” DVD with Kirk Douglas as Spartacus, Laurence Olivier, directed by Stanley Kubrick (1960) Amazon.com;

“The Spartacus War” by Barry S. Strauss (2009) Amazon.com

Types of Gladiator Contests

Kurion A variety of gladiator contests were staged. The combatants fought in specific categories, each with certain rules, weapons and armor. Based on their skill level, specialty and experience, they were paired off arena to match strengths with weaknesses to make contests exciting. Near naked Retiarii carried a net and Neptune-like trident and nimbly danced around the arena. Murmillos were the equivalent of heavyweight boxers. They carried heavy swords and shields and wore over 20 kilograms (45 pounds) of protective gear.. Samnites carried a large oblong shield, a sword or spear, and were protected by visored helmets, greaves on their right leg and a protective sleeve on the right arm.

Thraex (Thracians) had a distinctive crested bronze and curved sword, while secutors wore a helmet with just two eyeholes and carried a shield and sword resembling those used by Roman legionary soldiers. The classic gladiator battle pitted a murmillo armed with a sword, a helmet and a round shield against a retiarius armed only with a net and dagger, or a samnite equipped with a visor and a leather sheath protecting his right arm. Many gladiators were slaves who volunteered to fight in hopes that they that they would be freed as a reward for victory, or poor Romans who fought for monetary reward.

In one particularly unfair competition, an unarmed man was pitted against an armed man. The armed man of course usually won, but before he had a chance to savor his victory he was stripped of his weapons, which were given to another gladiator, who usually defeated the former victor. This process continued until every competitor was dead except for the last man.

Gladiator contests were often made the cloak of sordid murders and ruthless executions. Rome and even the municipia retained until the end of the third century the practice of proclaiming government-sponsored shows sine missione, that is to say, gladiatorial combats from which none might escape alive. The gladiatores meridiani, whose account was squared at the noon pause, were recruited exclusively from robbers, murderers, and incendiaries, whose crimes had earned them the death of the amphitheater: noxii ad gladium ludi damnati. Seneca has described this shameful procedure for us. The pitiable contingent of the doomed was driven into the arena. The first pair were brought forth, one man armed and one dressed simply in a tunic. The business of the first was to kill the second, which he never failed to do. After this feat he was disarmed and led out to confront a newcomer armed to the teeth, and so the inexorable butchery continued until the last head had rolled in the dust.massacre was even more hideous. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Did Gladiators Really Fight to the Death?

Secutor vs Retiarius, Foul"Death is the fighters' only exit," wrote the philosopher Seneca." When a victim fell dead or was fatally wounded he was approached by an official disguised as Charon, the ferryman of the Underworld." According to popular myth the gladiators at major events in Rome entered the stadium and faced the emperor and shouted: “We who are about to die salute you." If the loser fell exhausted or slightly wounded an appeal about his fate was made to the emperor, who usually bowed to the wishes of the crowd. If the emperor gave a thumbs up the man survived. If the decision was a thumbs down, Charon finished the gladiator off with a blow to the head with a wooden mallet. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

This it turns out was not completely right. According to Dutch historian Fik Meijer the “about to die” salute was uttered by the 9,000 prisoners who engaged in a mock sea battle organized by the Emperor Claudius, described by Suetonius, but was not necessarily said at other events. The statement didn't make sense for gladiators who hoped to defeat their opponents and live to fight another day. The exact nature of the up-or-down thumbs gestures or even what they looked like is unclear.

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic History: Most gladiators didn’t fight to the death. For every 10 gladiators who entered the ring, scholars estimate nine lived to see another day. However, occasionally death was the inevitable outcome, notably if the sponsor—the rich patron paying for the spectacle—demanded it. If the loser wasn’t to be spared, the winner was expected to deliver the final sword cut, typically a swift stab down through the neck to the heart. [Source Andrew Curry, National Geographic History, June 22, 2022]

If neither figure was capable at the end of a particularly bloody bout, a masked executioner, carrying a heavy hammer, was on hand to deliver the death blows. “Killing gladiators is done quickly and cleanly,” says John Coulston, an archaeologist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland. “It’s a professional courtesy between gladiators—if somebody is going to die, make it as painless as possible, and absolutely deadly.”

Brice Lopez, a gladiator afficionado and former French police officer, told National Geographic: Gladiators weren’t trying to kill each other; they were trying to keep each other alive. They spent years training in order to stage showy fights, most of which did not end in death. “It’s a real competition, but not a real fight,” says Lopez, who now runs a gladiator research and reenactment troupe called ACTA. “There’s no choreography, but there is good intent — you’re not my adversary; you’re my partner. Together we have to make the best show possible.” [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

Although death was uncommon, it was still an ever present risk, either in the ring or as a result of infections afterward. Audiences appreciated and rewarded the extra expense a dead gladiator represented. One Roman writer describes a particularly expensive show thrown by a young noble who recently had inherited a fortune. A staggering 400,000 sesterces bought him “the best steel, no running away, with the butchery done in the middle so the whole amphitheater can see.”

History of Gladiator Contests

Some say the first record of a gladiator contest was in 264 B.C.. Others say gladiator battles date back to 247 B.C., when two brothers decided to celebrate their father’s legacy by hosting a fight between their slaves. Many scholars believe that More likely they evolved out of Etruscan funerary rites. At first they were solemn affairs held at funerals as a blood offering for deceased heroes inspired perhaps by the Etruscans who it is said sometimes sacrificed slaves and prisoners during the burials of kings. The first Roman gladiator contests were hand-to-hand combats performed at funerals for prominent Romans to, according to Meijer. celebrate “the virtues that had made Rome great, virtues demonstrated by the deceased during his lifetime: strength, courage and termination." Over time these relatively solemn rituals evolved into gruesome competitions oriented towards satisfying the bloodthirsty appetite of mobs and boosting the prestige of emperors. One fan wrote a friend: “Let us go back to Rome. It might be rather nice, too, to see somebody killed." [Source: “Greek and Roman Life” by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum]

Gladiatorial combats seem to have been known in Italy from very early times. We hear of them first in Campania and Etruria. In Campania the wealthy and dissolute nobles, we are told, made slaves fight to the death at their banquets and revels for the entertainment of their guests. In Etruria the combats go back in all probability to the offering of human sacrifices at the burial of distinguished men, in accordance with ancient belief that blood is acceptable to the dead. The victims were captives taken in war, and it became the custom gradually to give them a chance for their lives by supplying them with weapons and allowing them to fight one another at the grave, the victor being spared, at least for the time. The Romans were slow to adopt the custom; the first exhibition was given in the year 264 B.C., almost five centuries after the assumed date of the founding of the city. That they derived it from Etruria rather than from Campania is shown by the fact that the exhibitions were at funeral games, the earliest at those of Brutus Pera in 264 B.C., Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in 216 B.C., Marcus Valerius Laevinus in 200 B.C., and Publius Licinius in 183 B.C. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

For the first one hundred years after their introduction the exhibitions were infrequent, as the dates just given show; those mentioned are all of which we have any knowledge during the period. But after that time they were given more and more frequently, with increasing elaboration. During the Republic, however, they remained in theory at least private games (munera), not public games (ludi), that is, they were not celebrated on fixed days recurring annually, and the givers of the exhibitions had to find a pretext for them in the deaths of relatives or friends, and to defray the expenses from their own pockets. In fact we know of but one instance in which actual magistrates (the consuls P. Rutilius Rufus and C. Manlius, 105 B.C.) gave such exhibitions, and we know too little of the attendant circumstances to warrant us in assuming that they acted in their official capacity. Even under the Empire the gladiators did not fight on the days of the regular public games. Augustus, however, provided the funds for “extraordinary shows” under the direction of the praetors. Under Domitian the aediles-elect were put in charge of the exhibitions which were given regularly in December, the only instance known of fixed dates for the munera gladiatoria. All others of which we read are to be considered the freewill offerings to the people of emperors, magistrates, or private citizens. |+|

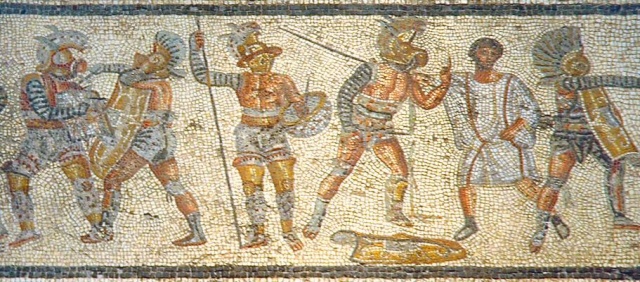

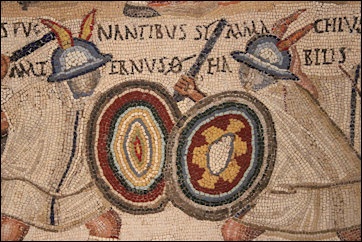

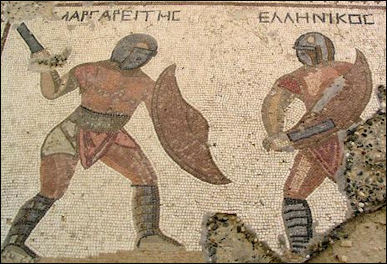

Gladiator contests were staged at the Colosseum and hundreds of smaller amphitheaters throughout the Roman Empire and had their heyday in the A.D. 1st and 2nd centuries. Some events were so brutal that fountains — scented with lavender to hide the stench of the blood — were set up. The wooden floor of the Colosseum was covered with sand so the combatants wouldn't slip on the blood. People enjoyed the sport so much they filled their homes with floor mosaics and wall frescoes of bloody gladiator scenes. Emperor Augustus boasted that in the eight gladiatorial contests that were staged during his rule 10,000 men fought to their death.

There are few eyewitness accounts of gladiator contests or detailed information about gladiator training and lifestyle. Historians have pieced together what the know about them today from pieces of verse, some historical accounts, mosaics, sculptures, funeral inscriptions and snatches of graffiti written on the walls of buildings and added little bit of conjecture to how battles might have unfolded between combatants with different weapons.

Places Gladiator Battles Took Place

During the Republic the combats of gladiators took place sometimes at a grave or in the circus, but regularly in the Forum. None of these places was well adapted to the purpose, the grave least of all. The circus had seats enough, but the spina was in the way and the arena too vast to give all the spectators a satisfactory view of a struggle that was confined practically to a single spot. In the Forum, on the other hand, the seats could be arranged very conveniently; they would run parallel with the sides, could be curved around the comers, and would leave free only sufficient space to afford room for the combatants. The inconvenience here was due to the fact that the seats had to be erected before each performance and removed after it, a delay to business if they were constructed carefully and a menace to life if they were put up hastily. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

These considerations finally led the Romans, as they had led the Campanians half a century before, to provide permanent seats for the munera, arranged as they had been in the Forum, but in a place where they would not interfere with public or private business. To these places for shows of gladiators came in the course of time to be exclusively applied amphitheatrum, a word which had been previously given in its general sense to any place, the circus for example, in which the seats ran all the way around, as opposed to the theater, in which the rows of seats were broken by the stage.

“Just when the first amphitheaters, in the special sense of the word, were erected at Rome cannot be determined with certainty. We are told that Caesar erected a wooden amphitheater in 46 B.C., but we have no detailed description of it, and no reason to think that it was anything more than a temporary structure. In the year 29 B.C., however, an amphitheater was built by Statilius Taurus, partly at least of stone, that lasted until the great conflagration in the reign of Nero (64 A.D.). Nero himself erected one of wood in the Campus.

Finally, by 80 A.D., was complete the structure known at first as the amphitheatrum Flavium, later as the Colosseum or Coliseum, which was large enough and durable enough to make forever unnecessary the erection of similar structures in the city. Remains of amphitheaters have been found in many cities throughout the Roman world. Those at Nîmes (Nemausus), and at Arles (Arelas), France, for instance, have been cleared and partly restored in modern times and are still in use, though bullfights have taken the place of the gladiatorial combats. The amphitheater at Verona, too, in northern Italy, has been partly restored. “Buffalo Bill” gave exhibitions there. “|+|

Pomp and Ceremony of Gladiator Fights

Government-sponsored shows usually lasted from dawn to dusk, although sometimes, as under Domitian, they were prolonged into the night. It was, therefore, all important to vary the fighting. were not, however, pitted against wild animals; such contests were reserved for the bestiarii. The day before the exhibition a banquet (cena libera) was given to the gladiators, and they received visits from their friends and admirers. The games took place in the afternoon. There was published program and a series of sham combats, the prolusio, with blunt weapons, were held before the real fighting began. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

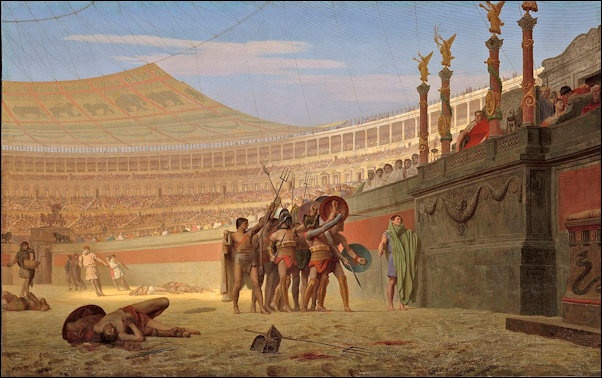

The government-sponsored show began with a parade. The gladiators, driven in. carriages from the Indus magnus to the Colosseum, alighted in front of the amphitheater and marched round the arena in military array, dressed in chlamys dyed purple and embroidered in gold. They walked nonchalantly, their hands swinging freely, followed by valets carrying their arms; and when they arrived opposite the imperial pulvinar they turned toward the emporer, their right hands extended in sign of homage, and addressed to him the justifiably melancholy saluation: "Hail, Emperor, those who are about to die salute thee! Ave, Imperator, morituri te salutantf" When the parade was over, the arms were examined (probatio armorum) and blunt swords weeded out, so that the fatal business might be expedited. Then the weapons were distributed, and the duellists paired off by lot. [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Professor Kathleen Coleman of Harvard University wrote for the BBC: “Gladiatorial displays were red-letter days in communities throughout the empire. The whole spectrum of local society was represented, seated strictly according to status. The combatants paraded beforehand, fully armed. Exotic animals might be displayed and hunted in the early part of the programme, and prisoners might be executed, by exposure to the beasts. As the combat between each pair of gladiators reached its climax, the band played to a frenzied crescendo. [Source: Professor Kathleen Coleman, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

Rules and Aims of a Gladiator Fight

Professor Kathleen Coleman of Harvard University wrote for the BBC: ““The combatants (as we know from mosaics, and from surviving skeletons) aimed at the major arteries under the arm and behind the knee, and tried to batter their opponent's skull. The thirst for thrills even resulted in a particular rarity, female gladiators. Above all, gladiatorial combat was a display of nerve and skill. The gladiator, worthless in terms of civic status, was paradoxically capable of heroism. Under the Roman empire, his job was one of the threads that bound together the entire social and economic fabric of the Roman world. [Source: Professor Kathleen Coleman, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

“When the people had had enough of this, the trumpets gave the signal for the real exhibition to begin. Those reluctant to fight were driven into the arena with whips or hot iron bars. If one of the combatants was clearly overpowered without being actually killed, he might appeal for mercy by holding up his finger to the editor. It was customary to refer the plea to the people, who signaled in some fashion not known to us to show that they wished it to be granted, or gesticulated pollice verso, apparently with the arm out and thumb down, as a signal for death. The gladiator to whom release (missio) was refused received without resistance the death blow from his opponent. Combats where all must fight to the death were said to be sine missione, but these were forbidden by Augustus. The body of the dead man was dragged away through the porta Libitinensis, sand was sprinkled or raked over the blood, and the contests were continued until all had fought. |+|

Sometimes defeated gladiators who were still alive but suffering were put to death like wounded animals. In the Pompeii amphitheater the was a special room where losers were put to death and relieved of their armor. Professor Kathleen Coleman of Harvard University wrote for the BBC: ““It was the prerogative of the sponsor, acting upon the wishes of the spectators, to decide whether to reprieve the defeated gladiator or consign him to the victor to be polished off. Mosaics from around the Roman empire depict the critical moment when the victor is standing over his floored opponent, poised to inflict the fatal blow, his hand stayed (at least temporarily) by the umpire.The figure of the umpire is frequently depicted in the background of an engagement, sometimes accompanied by an assistant. The minutiae of the rules governing gladiatorial combat are lost to modern historians, but the presence of these arbiters suggests that the regulations were complex, and their enforcement potentially contentious.” [Source: Professor Kathleen Coleman, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Referees and Fair Gladiator Fights

Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: Key figures were the referees, who were responsible for enforcing a strict sense of fair play. In one depiction, captured on a small pot found in the Netherlands, a referee holds up his staff to halt a fight as an assistant runs in with a replacement sword. “You don’t lose the fight because you lose your weapon,” Alain Genot, an archaeologist at the museum of antiquity in Arles, says. “When you imagine gladiator fights as a sporting event, you cannot imagine there are no rules.” Most important, inscriptions promising “fights without reprieve” — in other words, to the death — and “fights with sharp weapons” suggest life-threatening clashes were unusual enough to be worthy of special mention. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

To ensure exciting contests, fighting styles were carefully balanced. A nimble, near-naked fighter armed with only a net, trident, and small knife might face off against a lumbering warrior wearing 45 pounds of protective gear. Experienced gladiators were matched against other veterans, leaving new recruits to fight each other. The longer your career, the better your chances of survival, as each experienced gladiator represented years of investment. “There are hours and man-years going through all the fencing moves, building up the musculature, training for speed, strength, and endurance,” says Jon Coulston, an archaeologist at the University of St. Andrews. “Like modern football, it becomes a hugely capital-intensive enterprise.”

The marble Tombstone for the gladiator Diodorus dated to A.D. 2nd to 3rd century shows evidence of referees and a blown call made by them. Samsun in northern Turkey (ancient Amisus), it measures 46 by 30.5 centimeters (18 by 12 inches) and has the epitaph: “Here I lie victorious, Diodorus the wretched. After breaking my opponent Demetrius, I did not kill him immediately. But murderous Fate and the cunning treachery of the summa rudis killed me..." . According to Archaeology magazine: “Although Diodorus had, in fact, beaten his opponent Demetrius and taken his sword — the moment depicted on this marble tombstone — the referee intervened, allowing Demetrius to get up and keep fighting, a decision that led to Diordorus' demise. But was the referee, an official in the arena with the gladiators known as the summa rudis ("chief stick"), within his rights to make this call? Despite their great popularity in the Roman world, surprisingly little is known about the rules of gladiatorial contests. By focusing on the scene and the epitaph together, [Source: Archaeology magazine, Volume 64 Number 5, September-October 2011]

Roman historian Michael Carter of Brock University thinks he has found rare evidence that there were, in fact, rules that governed the combatants, including the right of the gladiator to submit before he was seriously harmed. The epitaph also makes it clear that the summa rudis was able to intervene in order to interpret the rules. Carter believes that understanding how the contests actually operated is key to understanding how spectators experienced this central social activity. "If this were simply murder on display," says Carter, "that's one thing. But since it seems to have been a spectacle of professional gladiators fighting according to established rules and procedures, then that is something quite different."

Main Events at a Gladiator Show

Sometimes it was decided to pit against each other only gladiators of the same category, while at other times gladiators were to oppose each other with different arms: a Samnite against a Thracian; a murmillo against a retiarius; or, to add spice to the spectacle, such freak combinations as African against African, as in the government-sponsored show with which Nero honored Tiridates, king of Armenia; or dwarf against woman, as in Domitian's government-sponsored show in A.D. 90.[Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

Then at the order of the president the series of duels opened, to the cacophonies of an orchestra, or rather a band, which combined flutes with strident trumpets, and horns with a hydraulic organ. The first pair of gladiators had scarcely come to grips before a fever, like that which reigned at the races, seized the amphitheater. As at the Circus Maximus the spectators panted with anxiety or hope, some for the Blues, others for the Greens, the spectators of the government-sponsored show divided their prayers between the parmularii (men armed with small shields) whom Titus preferred, or the scutarii (men armed with large shields) whom Domitian favored. Bets or sponsioncs were exchanged as at the ludi; and lest the result be somehow prearranged between the fighters, an instructor stood beside them ready to order his lorarii to excite their homicidal passion by crying "Strike! (verbera)" "Slay! (fejiifa)"; "Burn him! (ure)"-, and, if necessary, to stimulate them by thrashing them with leather straps (lora) till the blood flowed..At every wound which the gladiators inflicted on each other, the public trembling for its stakes reacted with increasing excitement. If the opponent of their champion happened to totter, the gamblers could not restrain their delight and savagely counted the blows "That's got him! (habet)"; "Now he's got it! (hoc habet)"\ and they thrilled with barbaric joy when he crumpled under a mortal thrust.

At once the attendants, disguised either as Charon or as Hermes Psychopompos, approached the prostrate form, assured themselves that he was dead by striking his forehead with a mallet, and waved to their assistants, the libitinarii, to carry him out of the arena on a stretcher, while they themselves hastily turned over the blood-stained sand. Sometimes it happened that the combatants were so well matched that there was no decisive result; either the two duellists, equally skilful, equally robust, fell simultaneously or both remained standing (st antes). The match was then declared a draw and the next pair was called. More often the loser, stunned or wounded, had not been mortally hit, but feeling unequal to continuing the struggle, laid down his arms, stretched himself on his back and raised his left arm in a mute appeal for quarter. In principle the right of granting this rested with the victor, and we can read the epitaph of a gladiator slain by an adversary whose life he had once spared in an earlier encounter. It professes to convey from the other world this fiercely practical advice to his successors: "Take warning by my fate. No quarter for the fallen, be he who he may! Moneo ut quis quern vicerit, occidat!" But the victor renounced his claim in the presence of the emperor, who often consulted the crowd before exercising the right thus ceded to him. When the conquered man was thought to have defended himself bravely, the spectators waved their handkerchiefs, raised their thumbs, and cried: "Mitte! Let him go!" If the emperor sympathised with their wishes and like them lifted his thumb, the loser was pardoned and sent living from the arena (missus). If, on the other hand, the witnesses decided that the victim had by his weakness deserved defeat, they turned their thumbs down, crying: "lugulat Slay him!" And the emperor calmly passed the death sentence with inverted thumb (pollice verso).'

The victor had, this time, escaped and he was rewarded on the spot. He received silver dishes laden with gold pieces and costly gifts, and taking these presents in his hands he ran across the arena amid the acclamations of the crowd. Of a sudden he tasted both wealth and glory. In popularity and riches this slave, this decadent citizen, this convicted criminal, now equalled the fashionable pantomimes and charioteers. At Rome as at Pompeii, where the graffiti retail his conquests, the butcher of the arena became the breaker of hearts : "decus fiuellarum, suspirium puellarum". But neither his wealth nor his luck could save him.

In the morning before the main gladiator clashes there were often animal events. In the animal against animal competitions staged in the arenas giraffes battled lions and zebras fought elephants in small pits that forced them to go after one another. Many animals were imported from Africa. During the inauguration of the Colosseum in Rome it was estimated that 5,000 wild animal were slaughtered in a single day. Decapitating ostriches with crescent-headed arrows was a favorite trick at gladiator battles. The crowds cheered and roared with laughter as the ostrich continued to run around after its head was cut off. Bears usually defeated bulls. Packs of hounds easily dispatched deers. Lions usually defeated tigers. Not even a rhino could penetrate the hide of an elephant. Gladiators were especially afraid of the battles against wild animals. Unarmed men battled starved lions. The odds were tipped in favor of the lions, which were more difficult to replace than the gladiators. Sometimes lawbreakers were fed to animals as a deterrent to keep others from breaking the law. There are accounts of women being fed to the animals.

Announcements and Activities at Gladiator Shows

Musicians played during the opening procession, as well as during the games. Andrew Curry wrote in National Geographic: Artwork from around the Roman world suggests that a colorful cast of helpers and hangers-on waited in the wings, or even shared the arena floor. Musicians warmed up the crowd as the gladiators took their places, and perhaps added dramatic flourishes during the fights. Helmets and weapons were carried into the ring during a prefight parade led by the editor, or sponsor of the games. And like any good sporting event, there were stats aplenty for fans to obsess over. Across the Roman world, gladiator wins, losses, and draws are scratched on walls and chiseled onto tombstones. The results of many matchups will never be known. But imagine the knot in the stomach of Valerius — who a scratched graffito at Pompeii reports survived 25 combats — as he faced off against Viriotas, a veteran of 150. [Source: Andrew Curry, National Geographic, July 20, 2021]

The games were advertised in advance by means of notices painted on the walls of public and private houses, and even on the tombstones that lined the approaches to the towns and cities. Some are worded in very general terms, announcing merely the name of the giver of the games with the date, [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

Others promise, in addition to the awnings, that the dust will be kept down in the arena by sprinkling. Sometimes when the troop was particularly good the names of the gladiators were announced in pairs as they would be matched together, with details as to their equipment, the school in which each had been trained, the number of his previous battles, etc. To such a notice on one of the walls in Pompeii someone added after the show the result of each combat.

The letters in italics before the names of the gladiators were added after the exhibition by some interested spectator, and stand for vicit, periit, and missus (“beaten, but spared”). To such particulars as those given above, other announcements added the statement that pairs other than those men would fight each day; these were meant to excite the curiosity and interest of the people. |+|

Fans at Gladiator Events

Franz Lidz wrote in Smithsonian magazine“The gladiator era was a time of strict law and order, when a family outing consisted of scrambling for a seat in the bleachers to watch people be sliced apart. “The circuses were a brutal, disgusting activity,” says LBI ArchPro senior researcher Christian Gugl. “But I suppose spectators enjoyed the blood, cruelty and violence for a lot of the same reasons we now tune in to ‘Game of Thrones.’ Rome’s throne games gave the public a chance, regularly taken, to vent its anonymous derision when crops failed or emperors fell out of favor. Inside the ring, civilization confronted intractable nature. In Marcus Aurelius: A Life, biographer Frank McLynn proposed that the beastly spectacles “symbolized the triumph of order over chaos, culture over biology....Ultimately, gladiatorial games played the key consolatory role of all religion, since Rome triumphing over the barbarians could be read as an allegory of the triumph of immortality over death.” [Source: Franz Lidz, Smithsonian magazine, July-August 2016]

Tolga İldun wrote in Archaeology magazine: Along with the private memorials to gladiators’ lives carved on grave stelas, public inscriptions and artwork provide additional information about both the fighters and the families that sponsored them. For example, a marble inscription erected in the agora of Ephesus in the third century A.D. names one of the Ephesian families who displayed a keen interest in sponsoring gladiatorial games. The inscription is dedicated to Marcus Aurelius Daphnos, who is described as an asiarch, a civil or priestly official who oversaw both religious rites and public games. His affiliation with a gladiator fan club called the Philoploi Philovedioi, or weapon-loving supporters of the Vedii family, is also mentioned. [Source Tolga İldun, Archaeology magazine, November-December, 2024]

The Vedii family were the wealthiest citizens of Ephesus in the second and third centuries A.D.—and may have sponsored the games in which Palumbos performed. The inscription reads: He was thrice asiarch of the temples in Ephesus, who held a munus (“games”) in his fatherland with thirty-nine pairs [of gladiators] fighting sharply for thirteen days, and who killed Libyan beasts, and who was favored by the emperors and wore at the front of the procession the golden crown as well as the purple robe. Those in this place who follow the Vedii, who love arms, honor him as their own euergetes (“benefactor”).

Associations of fans similar to the Philoploi Philovedioi are also known to have existed in the city of Miletus on the western coast of Anatolia, as well as in Hierapolis, where archaeologists have uncovered inscriptions relating to gladiatorial contests, including one that mentions a gladiator fan club known as the Friends of Arms.

Large Gladiator Events

The government staged gladiator battles three or four times a year. Spectators were often let into the stadiums and coliseums for free to win their support and keep them pacified. The last one was recorded in A.D. 404. There a monk ran into an arena and stopped a gladiator fight in mid battle. The monk was stoned to death but he left an impression on Emperor Honorius who banned the sport.

Crowds 45,000-strong showed up to watch gladiator battles at the Coliseum. An event hosted by Caesar contained 320 separate contests. Some bloody spectacles lasted for months.One bloody circus during Titus's rule lasted for 123 straight days and between 5,000 people and 11,000 were killed. Under Augustus eight large gladiator events were held, each with around 1,250 gladiators.

On large shows at the Colosseum: “Tom Mueller wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Following the executions came the main event: the gladiators. While attendants prepared the ritual whips, fire and rods to punish poor or unwilling fighters, the combatants warmed up until the editor gave the signal for the actual battle to begin. Some gladiators belonged to specific classes, each with its own equipment, fighting style and traditional opponents. For example, the retiarius (or “net man”) with his heavy net, trident and dagger often fought against a secutor (“follower”) wielding a sword and wearing a helmet with a face mask that left only his eyes exposed.

“Contestants adhered to rules enforced by a referee; if a warrior conceded defeat, typically by raising his left index finger, his fate was decided by the editor, with the vociferous help of the crowd, who shouted “Missus!” (“Dismissal!”) at those who had fought bravely, and “Iugula, verbera, ure!” (“Slit his throat, beat, burn!”) at those they thought deserved death. Gladiators who received a literal thumbs down were expected to take a finishing blow from their opponents unflinchingly. The winning gladiator collected prizes that might include a palm of victory, cash and a crown for special valor. Because the emperor himself was often the host of the games, everything had to run smoothly. The Roman historian and biographer Suetonius wrote that if technicians botched a spectacle, the emperor Claudius might send them into the arena: “[He] would for trivial and hasty reasons match others, even of the carpenters, the assistants and men of that class, if any automatic device or pageant, or anything else of the kind, had not worked well." Or, as Beste puts it, “The emperor threw this big party, and wanted the catering to go smoothly. If it did not, the caterers sometimes had to pay the price." [Source: Tom Mueller, Smithsonian magazine, January 2011]

“To spectators, the stadium was a microcosm of the empire, and its games a re-enactment of their foundation myths. The killed wild animals symbolized how Rome had conquered wild, far-flung lands and subjugated Nature itself. The executions dramatized the remorseless force of justice that annihilated enemies of the state. The gladiator embodied the cardinal Roman quality of virtus, or manliness, whether as victor or as vanquished awaiting the deathblow with Stoic dignity. “We know that it was horrible," says Mary Beard, a classical historian at University of Cambridge, “but at the same time people were watching myth re-enacted in a way that was vivid, in your face and terribly affecting. This was theater, cinema, illusion and reality, all bound into one."”

Roman Gladiator Arena Concession Stands

In March 2017, archaeologists in Austria announced they found the remains of the bakeries, fast-food stands and shops that could have been the equivalent of concessions stands for a 13,000-seat amphitheater in the ancient Roman city of Carnuntum, on the southern bank of the Danube, which at its height was the fourth-largest city in the Roman Empire, and home to maybe 50,000 people, including, for a time, A.D. second century A.D. philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius. [Source: Megan Gannon Livescience.com April 4, 2017 |~|]

Pompeii market stalls

In 2011, a team led by Wolfgang Neubauer, director of the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology (LBI ArchPro), identified a gladiator school at Carnuntum. In a later survey, using noninvasive methods, such as aerial photography, ground-penetrating radar systems and magnetometers, they found Carnuntum’s “entertainment district,” separate from the rest of the city and just outside the amphitheater. |~|

Megan Gannon wrote in Livescience.com: “They identified a wide, shop-lined boulevard leading to the amphitheater. By comparing the structures to buildings found at other well-preserved Roman cities, such as Pompeii, Neubauer and his colleagues identified several types of ancient businesses along the street. “Oil lamps with depictions of gladiators were sold all around this area,” Neubauer said, so some of the shops likely sold souvenirs. The researchers found a series of taverns and “thermopolia” where people could buy food at a counter. “It was like a fast-food stand,”Neubauer told Live Science. “You can imagine a bar, where the cauldrons with the food were kept warm.” |~|

“They also discovered a granary with a massive oven, which was likely used for baking bread. Material that has been exposed to high temperatures has a distinct geophysical signature, so when Neubauer’s team found a big, rectangular structure with that signature, they thought, “This must be an oven for baking.” “It gives us now a very clear story of a day at the amphitheater,” Neubauer said. The survey also revealed that there was once another, older wooden amphitheater, just 1,300 feet from the main amphitheater, buried under the later city wall of the civilian city.” |~|

Drawings Show Children Watched Gladiator Fights ‘To the Death’

Nick Squires wrote in The Telegraph: Children watched gladiators fighting to the death, newly discovered drawings in Pompeii suggest. Archaeologists in the Roman city discovered children’s drawings of the duels, suggesting youngsters were present at the events. The charcoal drawings were found on the wall of a courtyard and would have been made by children aged between five and seven, scholars said. [Source: Nick Squires, The Telegraph, May 29, 2024]

The stick figures depict a pair of gladiators confronting each other, each armed with a shield and a sword. In the background, two “bestiarii”, professional hunters who put on shows for baying crowds of Romans, use lances to prod two hairy creatures, most likely wild boars. On the right-hand side of the tableau is the head of a bird of prey, perhaps an eagle.In another room, archaeologists came across a drawing of a boxing match, with one fighter apparently having just delivered a knockout blow to his opponent. They also found the outline of three small hands, traced with charcoal.

Witnessing such brutal scenes must have had an impact on the psychological health of small children living in Pompeii, archaeologists said. The drawings are being studied by experts in child psychology from the University of Naples Federico II. Gabriel Zuchtriegel, the director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, said: “In all likelihood, the drawings of the gladiators and the hunters were based on direct experience rather than pictures. “One or more of the children who once played in the courtyard, between the kitchens, latrines and the vegetable gardens, would have seen fights in the amphitheater, coming into contact with an extreme form of violence which may have also included the execution of criminals and slaves. The drawings show us the impact of these images on a child of a tender age.” The stick figures are remarkably similar to the drawings of people that a child might produce today, he said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024