SPORTS IN ANCIENT ROMAN

The Romans transformed the athleticism and ritual of Greek sport into a spectacle. The Romans loved sports, some of which were quite brutal and bloody. Chariot racing and gladiator battles were fixtures of religious festivals. The huge crowds that gathered in stadiums and forums to watch sporting events screamed " panem at Colosseum !" ("bread and circuses"). Events were often sponsored by wealthy citizens as displays of their wealth. Horses and athletes were given-performance-enhancing drugs. Some racetracks were larger than NFL stadiums.

After the games of childhood, the Roman did not, as we do, pass on to an elaborate system of competitive games. Of sport in that sense he knew nothing. He played ball before dinner for the good of the exercise. He practiced riding, fencing, wrestling, hurling the discus, and swimming for the skill in arms and the strength they gave him. In the country there might be hunting and fishing. He played a few games of chance for the excitement the stakes afforded. But there was no national game for the young men, and there were no social amusements in which men and women took part together. The Roman made it hard and expensive, too, for others to amuse him. He cared more for farces (mimes and pantomimes) than for the drama, tragic or comic; but the one thing that really appealed to him was excitement, and this he found in gambling or in such amusements only as involved the risk of injury to life and limb—the sports of the circus and the amphitheater. We may describe first the games in which the Roman himself participated and then those at which he was a mere spectator. In the first class are field sports and games of hazard, in the second the public and private games (ludi publici et privati). [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

RELATED ARTICLES:

RECREATION IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

GAMES AND GAMBLING IN ANCIENT ROME europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN CHARIOT RACING: HISTORY, TEAMS, FANS, HORSES AND FAME europe.factsanddetails.com

CIRCUSES — WHERE ROMAN CHARIOT europe.factsanddetails.com

PUBLIC GAMES AND SHOWS OF THE ROMAN EMPERORS europe.factsanddetails.com

AMPHITHEATERS IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE — WHERE GLADIATOR EVENTS europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM: HISTORY, IMPORTANCE AND ARCHAEOLOGY europe.factsanddetails.com

ROMAN COLOSSEUM SPECTACLES europe.factsanddetails.com

ANIMAL SPECTACLES IN ANCIENT ROME: KILLING AND BEING KILLED BY WILD ANIMALS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATORS: HISTORY, POPULARITY, BUSINESS europe.factsanddetails.com

GLADIATOR CONTESTS: RULES, EVENTS, HOW THEY WERE RUN europe.factsanddetails.com

TYPES OF GLADIATORS: EVENTS, WEAPONS, STYLES OF FIGHTING europe.factsanddetails.com

Websites on Ancient Rome: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history; Perseus Project - Tufts University; perseus.tufts.edu ; Lacus Curtius penelope.uchicago.edu; British Museum ancientgreece.co.uk; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; The Internet Classics Archive classics.mit.edu ; Bryn Mawr Classical Review bmcr.brynmawr.edu; Cambridge Classics External Gateway to Humanities Resources web.archive.org; Ancient Rome resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library web.archive.org ; History of ancient Rome OpenCourseWare from the University of Notre Dame web.archive.org ; United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History unrv.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Ancient Roman Sports, A-Z: Athletes, Venues, Events and Terms” by David Matz Amazon.com;

“Beyond the Coliseum Sporting Culture in Ancient Rome”, Kindle Edition,

by Oriental Publishing Amazon.com;

“The Victor's Crown: A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium”

by David Potter Amazon.com;

“The Roman Games: A Sourcebook (Blackwell) by Alison Futrell Amazon.com;

“Roman Sports and Spectacles: A Sourcebook” by Anne Mahoney Amazon.com;

“Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Donald G. Kyle Amazon.com;

“Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire” by Jason König (2005) Amazon.com;

”Athletics and Philosophy in the Ancient World” by Heather Reid (2012)

Amazon.com;

“Chariot Racing in the Roman Empire” by Fik Meijer, Liz Waters (2010) Amazon.com;

“Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing” by John H. Humphrey Amazon.com;

“Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture” by Michael Poliakoff (1987) Amazon.com;

“Gladiator: The Complete Guide To Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters”, Illustrated,

by Konstantin Nossov (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport”, Illustrated, by Fik Meijer (2007) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World” by Alison Futrell, Thomas F. Scanlon (2021) Amazon.com;

“Spectacle in the Roman World” by Hazel Dodge (2011) Amazon.com;

“The Day Commodus Killed a Rhino: Understanding the Roman Games” (Witness to Ancient History) by Jerry Toner (2015) Amazon.com;

“Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power” by Alison Futrell (1997) Amazon.com;

“Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome” by Donald G. Kyle (2012) Amazon.com;

“Life and Leisure in Ancient Rome” by J.P.V.D. Balsdon (1969) Amazon.com;

“Roman Life: 100 B.C. to A.D. 200" by John R. Clarke (2007) Amazon.com;

“Daily Life in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook” by Brian K. Harvey Amazon.com;

“Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome” by Lesley Adkins and Roy A. Adkins (1998) Amazon.com

Spectator Sports in Ancient Rome

Romans appear to have been more interested in gladiator battles, chariot races and large spectacles and less interested in drama and Olympic-style sports as was the case with ancient Greeks. The Olympics, however, continued through the Roman era as a pagan festival, with Nero among those that attended, until they were shut down by the Christian Roman emperor Theodosius I, who ordered the closure of all pagan events in 393.

Children games

Sporting events in ancient Rome often got out of hand. The incidents usually began with spectators hurling insults at one another, then escalated into stone throwing melees and often ended in carnage when the combatants picked up weapons. After one such incident in Pompeii, Emperor Nero forbade all such gatherings for ten years. An even worse episode occurred at the Constantinople Hippodrome under the Byzantines when over 30,000 people were killed when a chariot race turned into riot against Emperor Justinian."*

Arenas and amphitheaters that hosted sporting events were found throughout the Roman empire. A massive oak amphitheater excavated in London had chambers for wild animals and shrines used by gladiators who prayed before their battles and possible deaths. The arena had a seating capacity of 6,000, quite large when considering that London at the time only had 20,000 residents.

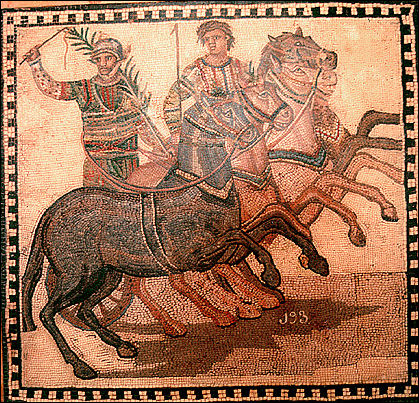

The circus was mainly used for chariot races. But other sports were held there. Of these may be mentioned the performances of the desultores, men who rode two horses and leaped from one to the other while they were going at full speed, and of trained horses that performed various tricks while standing on a sort of wheeled platform which gave a very unstable footing. There were also exhibitions of horsemanship by citizens of good standing, riding under leaders in squadrons, to show the evolutions of the cavalry. The ludus Troiae was also performed by young men of the nobility; this game is described in the Aeneid, Book V. More to the taste of the crowd were the hunts (venationes); wild beasts were turned loose in the circus to slaughter one another or be slaughtered by men trained for the purpose. We read of panthers, bears, bulls, lions, elephants, hippopotamuses, and even crocodiles (in artificial lakes made in the arena) exhibited during the Republic. In the circus, too, combats of gladiators sometimes took place, but these were more frequently held in the amphitheater. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

Olympics and Sports Festivals in Ancient Rome

The Ancient Olympic Games were held throughout the Roman era. They ended in A.D. 393 when Roman Emperor Theodosius I banned them to promote Christianity. Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast The Romans were Hellenophiles and sports fans and, after conquering the Peloponnese, they sponsored building projects to house athletes and wealthy spectators. In 67 CE, the emperor Nero ordered that the games be held two years early so that he could compete. According to his gossipy biography Suetonius, Nero was somewhat horse-mad and rode his chariot at Olympia (24.2). When he was thrown from the chariot and was unable to finish the race he still received a victor’s crown and, upon returning to Italy, demanded that a wall of the city of Naples be demolished in his honor. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, July 25, 2021]

The ludi were games that focused on chariot racing. According to the Encyclopedia of Religion: They went back to an old tradition represented by the Equirria. The new ludi replaced the bigae, teams of two horses, with the quadrigae, teams of four, for the races in the Circus Maximus and included various performances: riders leaping from one horse to another, fights with wrestlers and boxers. (The gladiator fights, which were Etruscan in origin, appeared in 264 B.C. for private funeral feasts, but they did not become part of the public games until the end of the second century B.C.) These competitions were soon complemented by other spectacles: pantomimes and dances accompanied by the flute. [Source: Robert Schilling (1987), Jörg Rüpke (2005),Encyclopedia of Religion, Encyclopedia.com]

The principal ones were the Ludi Magni or Ludi Romani, celebrated from the fifteenth through the eighteenth of September after the ides that coincided with the anniversary of the temple of Jupiter Capitoline. Considered to have been instituted by Tarquin the Elder (Livy, 1.35.9), they became annual events starting in 367 B.C., which is the date that saw the creation of the curule magistracy (aediles curules). The Ludi Plebei, a kind of plebeian reply to preceding games, were instituted later: they are mentioned for the first time in 216 B.C. (Livy, 23.30.17). They took place in the Circus Flaminius, involved the same kind of games as the Ludi Romani, and were celebrated around the ides of November. It is also noteworthy that the Ludi Romani and the Ludi Plebei were both held around the ides (of September or November) and dedicated to Jupiter, to whom a sacrificial meal, the Epulum Iovis, was offered.

One of the most brilliant spectacles must have been the procession (pompa circensis) which formally opened some of the public games. It started from the Capitol and wound its way down to the Circus Maximus, entering by the porta pompae (named from it), and passed entirely around the arena. At the head in a car rode the presiding magistrate, wearing the garb of a triumphant general and attended by a slave who held a wreath of gold over his head. Next came a crowd of notables on horseback and on foot, then the chariots and horsemen who were to take part in the games. Then followed priests, arranged by their colleges, and bearers of incense and of the instruments used in sacrifices, and statues of deities on low cars drawn by mules, horses, or elephants, or else carried on litters (fercula) on the shoulders of men. Bands of musicians headed each division of the procession. A feeble reminiscence of all this is seen in the parade through the streets that for many years has preceded the performance of the modern circus. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932)]

Types of Sports in Ancient Rome

entertainment at the Satyricon

Sports enjoyed in Roman times included boxing, acrobatics, tightrope walking, animal chases, animal bating and cockfighting. Boxing was popular. Some boxers were known for their skill; others were known for simply being able take punishment. Bullfights were held in the Roman theater in Arles, France. Virgil makes a reference to rowing as a sport competition around 25 B.C. in the Aeneid . Cockfighting predates Christ by at least 500 years. Believed to have originated in China or India, it was practiced by the ancient Greeks, Persians and Romans, who identified it with Eros, the God of Love and passed it on to medieval Europe.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Public games were a major part of Roman culture, playing an important role in the social and political life of the city and its empire. Although the games had their roots in funeral or religious rites, by the late Republican period (ca. 70–31 B.C.), they had become a hugely popular form of public entertainment. They took several forms but all were essentially either races or fights. Known as ludi and munera, games could be staged in purpose-made arenas, most notably the Colosseum and Circus Maximus in Rome, either separately or combined in lengthy festivals. [Source: Jacob Coley, Department of Greek and Roman Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 2010, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The oldest games in Rome were the chariot races. Typical chariots used for the races were drawn by a team of four horses (quadriga). The races required two long tracks and two 180-degree turns. Like gladiatorial shows and boxing, races were extremely dangerous, since chariots often collided or went out of control. If a driver fell out of his chariot, he could easily be dragged along or trampled to death by the horses. Nevertheless, there was no shortage of drivers, as eager young charioteers risked their lives for reward and recognition. \^/

“Roman boxing, far different than the boxing developed by the Greeks, was considered more of a gladiatorial show than an athletic contest. While the crowds were smaller than at the amphitheater and circus, boxing was an important part of public entertainment. Unlike Greek boxers, who wore leather thongs around their knuckles for protection and performed for prizes at the prestigious Panhellenic games, Romans used gloves with pieces of metal placed around the knuckles (caestus) to inflict the most damage possible. Moreover, there was no time limit or weight classification. Proclaiming a winner resulted from either a knockout or the conceding of defeat by one of the boxers. \^/

“The most famous games were the gladiatorial shows, where armed men fought each other in violent, often mortal, combat for fame, fortune, and even freedom. The gladiators would first train at a ludus, a professional fighting school, to prepare for their debut in the arena. Originally these schools drew their recruits from among the lowest ranks of society—slaves, convicts, and prisoners of war—but by the first century A.D., contracted free men, retired soldiers , and even, on rare occasions, women participated in the fights. \^/

“The games could also be used as a form of public execution for condemned criminals, who were brought to the arena to be crucified (crucifixio), burned alive (crematio or A.D. flammas), put to the sword (ad gladium), or killed by wild animals (ad bestias). Each penalty was differentiated according to one's station and social class. The games involved animals on a massive scale. In addition to horses used in the circus and amphitheater, exotic wild animals were paraded before the public not just for the sheer spectacle but also to play an active role in the games as either the hunted or the hunter.” \^/

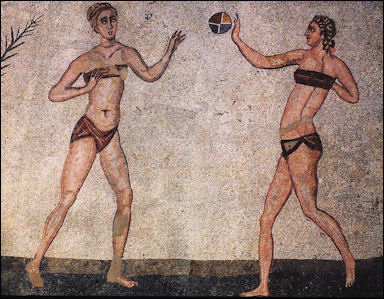

Ball Games in Ancient Rome

The Egyptians, Greeks and Romans played ball games. The Romans played a ball game called trugon with three players on each team. It was similar to netball and was mentioned by Martial and Horace. Haroastum was another ball game that required footwork and ball-handling skills. A 1,600-year-old fresco found at a villa in Sicily showed a pair of bikini-clad women tossing a ball.

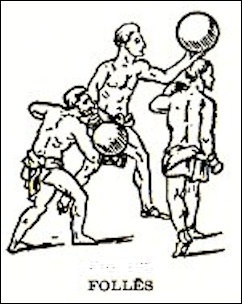

Balls of different sizes, variously filled with hair, feathers, and air (folles), are known to have been used in the different games. Throwing and catching formed the basis of all the games; the bat was practically unknown. In the simplest game the player threw the ball as high as he could and tried to catch it before it struck the ground. Variations of this were what we should call juggling: the player kept two or more balls in the air, throwing and catching by turns with another player. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Another game must have resembled our handball; it required a wall and smooth ground at its foot. The ball was struck with the open hand against the wall, allowed to fall back upon the ground and to bound, and then struck back against the wall in the same manner. The aim of the player was to keep the ball going in this way longer than his opponent could. Private houses and the public baths often had courts especially prepared for this amusement. |+|

“A third game was called trigon, and was played by three persons stationed at the angles of an equilateral triangle. Two balls were used and the aim of the player was to throw the ball in his possession at the one of his opponents who would be the less likely to catch it. As two might throw at the third at the same moment, or as the thrower of one ball might have to receive the second ball at the very moment of throwing, both hands had to be used, and a good degree of skill with each hand was necessary. Other games, all of throwing and catching, are mentioned here and there, but none is described with sufficient detail to be clearly understood.” |+|

Games Played at Ancient Roman Baths

In the 1st-century AD Roman work of fiction Satyricon by Petronius, we main character Trimalchio meets with his friends before a grand banquet at bath time in the thermae where many people have gathered. Suddenly they spy "a bald old man in a reddish shirt playing at ball with some long-haired boys.... The old gentleman, who was in his house shoes, was busily engaged with a green ball. He never picked it up if it touched the ground. A slave stood by with a bagful and supplied them to the players." [Source: “Daily Life in Ancient Rome: the People and the City at the Height the Empire” by Jerome Carcopino, Director of the Ecole Franchise De Rome Member of the Institute of France, Routledge 1936]

This was a ball game for three, called a trigon, in which the players, each posted at the corner of a triangle, flung the balls to and fro without warning, catching with one hand and throwing with the other. The Romans had many other kinds of ball games, including "tennis" played with the palm of the hand for a racquet (as in the Basque game of pelote) ; harpastum, in which the players had to seize the ball, or harpastum, in the middle of the opponents, despite the shoving, bursts of speed, and feints a game which was very exhausting and raised clouds of dust; and many others such as "hop-ball," "ball against the wall," etc. The harpastum was stuffed with sand, the paganica with feathers; the folks was blown full of air and the players fought for it as in basket ball, but with more elegance. Sometimes the ball was enormous and filled with earth or flour, and the players pommelled it with their fists like a punching bag, in much the same way that they sometimes lunged with their rapiers against a fencing post. These were some of the games which formed a prelude to the bath. Martial alludes to them in an epigram addressed to a philosopher friend who professed to disdain them: "No hand-ball, no bladder-ball, no feather-stuffed ball makes you ready for the warm bath, nor the blunted stroke upon the unarmed stump; nor do you stretch forth squared arms besmeared with sticky ointment, nor, darting to and fro, snatch the dusty scrimmage-ball."

This enumeration is far from complete and we must add simple running, or rolling a metal hoop (trochus), Steering the capricious hoop with a little hooked stick which they called a "key" was a favorite sport of women; and so was swinging what Martial called "the silly dumb-bell" (haltera), though they tired at this more quickly than the men. When playing these games both men and women wore either a tunic like Trimalchio's, or tights like those of the manly Philaenis when she played with the harpastum or a plain warm cloak of sports cut like the endromis which Martial sent to one of his friends with the gracious message : "We send you as a gift the shaggy nursling of a weaver on the Seine, a barbarian garb that has a Spartan name, a thing uncouth but not to be despised in cold December,.. whether you catch the warming hand-ball, or snatch the scrimmage-ball amid the dust, or bandy to and fro the featherweight of the flaccid bladder-ball."

For the wrestling match, on the other hand, the wrestlers had to strip completely, smear themselves with ceroma (an unguent of oil and wax which made the skin more supple), and cover this with a layer of dust to prevent their slipping from the opponent's hands. Wrestling took place in the palaestrae of the central building near some rooms which in the baths of Caracalla archaeologists have identified with the oleoteria and the conisteria. Here not only wrestler but wrestleress whose perverse complaisance under the masseur's attentions roused the wrath of Juvenal came to submit to the prescribed anointings and massage.

Working Out at the Campus Martius

athlete

The Campus Martius, often called simply the Campus included all the level ground between the Tiber and the Capitoline and Quirinal Hills. The northwestern portion of this plain, bounded on two sides by the Tiber, which here sweeps abruptly to the west, was kept clear of public and private buildings and was for centuries the playground of Rome. [Source: “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932) |+|]

“Here the young men gathered to practice the athletic games mentioned above, naturally in the cooler parts of the day. Even men of graver years did not disdain a visit to the Campus after the meridiatio, in preparation for the bath before dinner, instead of which the younger men preferred to take a cool plunge in the convenient river. The sports themselves were those that we are accustomed to group together as track and field athletics. |+|

“The men ran foot races, jumped, threw the discus, practiced archery, and had wrestling and boxing matches. These sports were carried on then much as they are now if we may judge by Vergil’s description in Book V of the Aeneid, but an exception must be made of the games of ball. These seem to have been very dull as compared with ours. It must be remembered, however, that they were played more for the healthful exercise they furnished than for the joy of the playing, and by men of high position, too—Caesar, Maecenas, and even the Emperor Augustus.” |+|

Boxing in Ancient Rome

A pair of Roman leather boxing gloves — dated A.D. 117–119 and measuring 13.5 x 8.3 centimeters (5.3 by 3.3 inches) and 15.5 x 13 centimeters (6.1 by 5.1 inches) — was found at Vindolanda, a military complex in Northumberland, England. [Source: Jarrett A. Lobell, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2018]

Jarrett A. Lobell wrote in Archaeology magazine: Boxing is mentioned in Homer’s Iliad and was practiced at the Olympics beginning in the seventh century B.C. There are life-size Hellenistic bronze sculptures of boxers, and depictions of boxers from the classical world decorate Minoan wall paintings, Athenian vases, and Roman mosaics.

“No actual boxing gloves, however, had been found until recently, when, at the Roman fort of Vindolanda near Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, these two examples were discovered on the floor of a cavalryman’s barrack alongside a pile of horse gear, shoes, wooden bath clogs, gaming counters, and a nearly complete sword. “There are references to boxing in the Roman army,” says site director Andrew Birley. It must have been seen as a good form of training, exercise, and entertainment.

“What is so interesting about the gloves, though, is that, while similar, they are also different from each other. The smaller of the two is soft and has layers of interwoven leather in the glove’s main padding. You can still see the imprint of the boxer’s knuckles in the leather.” Birley thinks this is a sparring glove, “offering good protection to the wearer and moderate protection to the person being punched.” The other, larger glove was filled with straw and offered ample protection for the knuckles, but also had an additional feature — a heat-hardened leather strip wound around an edge that would easily draw blood if used in a slashing motion. “One glove is for practice,” says Birley, “and one is for fighting.”

Roman Wrestling Was Fixed

A papyrus dating from A.D. 267 found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, when it was part of the Roman Empire, “ is the first known bribery contract for sports. In it a wrestler agreed to throw a match for around 3,800 drachmas—enough to buy a donkey. It is presumed that because the amount was relatively small and wrestling competitions were popular, other wrestlers made similar deals. [Source: Gordon Gora. Listverse, September 16, 2016]

Elizabeth Quill wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “The smackdown was set for a day in the 14th year of the Roman emperor Gallienus in the city of Antinoopolis, on the Nile: A final bout in the sacred games honoring a deified youth named Antinous featured teenage wrestlers named Nicantinous and Demetrius. It promised to be a noble spectacle—except the fix was in. This papyrus, found in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt, and dating to A.D. 267, is apparently the first known bribery contract in ancient sports. In the text, recently deciphered, translated and interpreted by Dominic Rathbone of King’s College London, Demetrius agrees to throw the match for 3,800 drachmas, about enough to buy one donkey. That “seems rather little,” says Rathbone. Winning athletes would typically be greeted home with a triumphant entry and would receive a sizable cash pension. [Source: Elizabeth Quill, Smithsonian Magazine, July 2014]

“Other written accounts suggest bribery was fairly common during ancient sporting events. Fines imposed on athletes who violated the integrity of their games helped fund the construction of bronze statues of Zeus at Olympia, for example. In his writings, the Greek sophist Philostratus complains of the degeneration of athletics, blaming trainers who “have no regard for the reputation of the athletes, but become their advisers on buying and selling with a view to their own profits.”

“Found in the winter of 1903-04 during an excavation at Oxyrhynchus, among Egypt’s most important archaeological sites, the contract is nearly complete, except for the right side where the second half of several lines are missing. Currently owned by the Egypt Exploration Society, it is held at the Sackler Library at Oxford University.”

Greco-Roman Chariot Races

The Olympics games often kicked off with a race involving 40 chariots flying through a course at one time with spectacular spills and frequent deaths. Often only a handful of the chariots that started made it to the finish line.

The chariots started in a staggered fashion so that those on the outside were not at a disadvantage. Competitions were held for two, three and four horse chariots, usually driven by hired professional, essentially slaves, owned by the sponsors. They lived in stables and were breed like horses from the offspring of famous charioteers. Despite their lowly background successful charioteers were celebrated heros and the best ones earned enough money to buy their freedom. [Source: “Greek and Roman Life? by Ian Jenkins from the British Museum [||]

Winner of a Roman chariot race Competitors were often killed. Describing an accident Sophocles wrote: “As the crowd saw the driver somersault, there rose a wail of pity for the youth as he was bounced onto the ground , then flung head over heels into the sky. When his companions caught the runaway team and freed the bloodstained corpse from his reigns he was disfigured and marred past the recognition of his best friend."

"A two-wheeled chariot," wrote journalist Lionel Cassonin Smithsonian magazine, "was light, like a modern trotters' gig, but pulled by a team of four horses that would be driven at the fastest gallop they could generate. They made 12 laps around the course — about nine kilometers — with 180 degree turns at each end. As at our Indianapolis 500 viewers enjoyed not only the excitement of the race but the titillation that comes from the constant presence of danger: as the teams thundered around the turns, or one chariot tried to cut over from the outside to the inside, crashes and collisions were common and doubtless often fatal. In one celebrated race in the Pythian games, the competition was so lethal that only one competitor managed to finish!" [Lionel Casson, Smithsonian, February 1990]

Hippodromes were where horse races and chariot races were held. Built in 330 B.C. the Hippodrome in what is now Istanbul was the largest stadium in the ancient world. Horse races and gladiator vs. animal battles were held here in front crowds so rowdy they make British soccer hooligans look like saints. During one event in A.D 532 that turned into an angry political rally against Emperor Justinian, the Byzantine army massacred 30,000 people. All sporting events were cancelled for a few years after that but when they resumed, chariot races continued for another 500 years.

See Separate Article: ANCIENT ROMAN CHARIOT RACING europe.factsanddetails.com

Nero at the Olympics

Suetonius wrote: “He introduced a musical competition at Olympia also, contrary to custom. To avoid being distracted or hindered in any way while busy with these contests, he replied to his freedman Helius, who reminded him that the affairs of the city required his presence, in these words: "However much it may be your advice and your wish that I should return speedily, yet you ought rather to counsel me and to hope that I may return worthy of Nero." While he was singing no one was allowed to leave the theater even for the most urgent reasons. And so it is said that some women gave birth to children there, while many who were worn out with listening and applauding, secretly leaped from the wall, since the gates at the entrance were closed, or feigned death and were carried out as if for burial. [Source: Suetonius (c.69-after 122 A.D.) : “De Vita Caesarum: Nero: ” (“The Lives of the Caesars: Nero”), written in A.D. 110, 2 Vols., translated by J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library (London: William Heinemann, and New York: The MacMillan Co., 1914), II.87-187, modernized by J. S. Arkenberg, Dept. of History, Cal. State Fullerton]

The trepidation and anxiety with which he took part in the contests, his keen rivalry of his opponents and his awe of the judges, can hardly be credited. As if his rivals were of quite the same station as himself, he used to show respect to them and try to gain their favor, while he slandered them behind their backs, sometimes assailed them with abuse when he met them, and even bribed those who were especially proficient. Before beginning, he would address the judges in the most deferential terms, saying that he had done all that could be done, but the issue was in the hand of Fortuna; they however, being men of wisdom and experience, ought to exclude what was fortuitous. When they bade him take heart, he withdrew with greater confidence, but not even then without anxiety, interpreting the silence and modesty of some as sullenness and ill-nature, and declaring that he had his suspicions of them.

“In competition he observed the rules most scrupulously, never daring to clear his throat and even wiping the sweat from his brow with his arm [the use of a handkerchief was not allowed; see also Tac. Ann. 16.4]. Once, indeed, during the performance of a tragedy, when he had dropped his scepter but quickly recovered it, he was terribly afraid that he might be excluded from the competition because of his slip, and his confidence was restored only when his accompanist [the "hypocrites" made the gestures and accompanied the tragic actor on the flute, as he spoke his lines] swore that it had passed unnoticed amid the delight and applause of the people. When the victory was won, he made the announcement himself; and for that reason he always took part in the contests of the heralds. To obliterate the memory of all other victors in the games and leave no trace of them, their statues and busts were all thrown down by his order, dragged off with hooks, and cast into privies. He also drove a chariot in many places, at Olympia even a ten-horse team, although in one of his own poems he had criticized Mithridates for just that thing. But after he had been thrown from the car and put back in it, he was unable to hold out and gave up before the end of the course; but he received the crown just the same. On his departure he presented the entire province with freedom [That is, with local self-government, not with actual independence], and at the same time gave the judges Roman citizenship and a large sum of money. These favors he announced in person on the day of the Isthmian Games, standing in the middle of the stadium.

Nero

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Rome sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Late Antiquity sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; “Outlines of Roman History” by William C. Morey, Ph.D., D.C.L. New York, American Book Company (1901) ; “The Private Life of the Romans” by Harold Whetstone Johnston, Revised by Mary Johnston, Scott, Foresman and Company (1903, 1932); BBC Ancient Rome bbc.co.uk/history/ ; Project Gutenberg gutenberg.org ; Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Live Science, Discover magazine, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopedia.com and various other books, websites and publications.

Last updated November 2024