PHOENICIAN SEAFARERS

The Phoenicians were the greatest seafaring civilization of the ancient world. Hailing from modern-day Lebanon, they were capable of sailing great distances and dominated trade in the Mediterranean for nearly a thousand years. The word “Phoenician” is Greek for "People of the Sea."

According to Archaeology magazine: From a home along the coast of present-day Lebanon, at the outset of the first millennium B.C. ., Phoenician sailors were crisscrossing the Mediterranean, establishing trading outposts as far away as Morocco and Portugal. They made the world smaller by linking the eastern and western Mediterranean shores in a way that no other civilization previously had. By the turn of the first millennium B.C. ., the Phoenicians had developed into the foremost naval and commercial power in the eastern Mediterranean, controlling the major maritime trade routes between ancient Near Eastern cultures. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

"The Phoenicians are not the first ones sailing the sea," says Brown University archaeologist Peter van Dommelen. "People have been going around and trading stuff for a very long time. The Phoenicians, however, are the long-distance traders of the world. They are the ones making long-distance connections."

The Phoenicians were merchant marines. Their ships traveled under many flags. From what can best be ascertained Phoenician ships had crews of about a half dozen sailors and the typical meal was fish stew. Seamen carried images of god to protect them from storms and pirates. Incense offerings to the gods were made at the beginning and end of every voyage. They might also have also been lit on voyages during violent storms.

Websites on Mesopotamia: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; International Association for Assyriology iaassyriology.com ; Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, University of Chicago isac.uchicago.edu ; University of Chicago Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations nelc.uchicago.edu ; University of Pennsylvania Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations (NELC) nelc.sas.upenn.edu; Penn Museum Near East Section penn.museum; Ancient History Encyclopedia ancient.eu.com/Mesopotamia ; British Museum britishmuseum.org ; Louvre louvre.fr/en/explore ; Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah ; Ancient Near Eastern Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org; Iraq Museum theiraqmuseum ABZU etana.org/abzubib; Archaeology Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Phoenicians and the Making of the Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians and the West” by María Eugenia Aubet (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Lost Colonies of Ancient America: A Comprehensive Guide to the Pre-Columbian Visitors Who Really Discovered America” by Frank Collin) Amazon.com;

“Out of Arabia: Phoenicians, Arabs, and the Discovery of Europe” by Warwick Ball (2009) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Secrets: Exploring the Ancient Mediterranean” by Sanford Holst (2011) Amazon.com;

“Phoenicians: Lebanon's Epic Heritage” by Sanford Holst (2005) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Civilization: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: The Purple Empire of the Ancient World ” by Gerhard Herm (1973) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: Lost Civilizations” by Vadim Jigoulov (2022) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Phoenicians” by Josephine Quinn (2017) Amazon.com;

"The Phoenicians" by Donald Harden Amazon.com;

"Phoenicians" by Glenn Markoe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

“Warships of the Ancient World: 3000–500 BC” by Adrian K. Wood, Giuseppe Rava (Illustrator) (2013) Amazon.com;

“Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World” by Lionel Casson (1995) Amazon.com;

“Ancient Boats and Ships” by Sean McGrail (2008) Amazon.com;

“On Ancient Galleys: And Their Mode of Propulsion”

by William Schaw Lindsay (1871) Amazon.com;

“The Ancient Mariners: Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Mediterranean in Ancient Times” by Lionel Casson Amazon.com;

Phoenician Navigation Skills

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Among ancient Mediterranean cultures, the Phoenicians were renowned for both their superb maritime capabilities and their aptitude for trade. The Roman historian Velleius Paterculus characterized them as the "fleet that controlled the sea." In Homer’s Odyssey, they are called the "men famed for their ships." In the Bible, the prophet Ezekiel refers to the Phoenician city of Tyre as "the merchant to the peoples of many coastlands."

Phoenician seafarer usually hugged the coast and set up their colonies and camps on easily defended islands or peninsulas. They determined their direction by looking at the sun and the stars. For many years the North Star was known as the Phoenician Star.

The Phoenician sailed mostly during the day and only in good weather between March and October. They headed to shore the first sign of a storm or some other problem. They traveled around five knot an hour. They could make 100 miles in 24 hours but usually traveled around 25 to 30 miles.

Phoenician Trade

Pliny once wrote, the "Phoenicians invented trade." Phoenicians engaged in three types of trading activities; 1) exporting material, namely cedar, from their traditional homeland in Lebanon; 2) earning transport and middleman fees from shipping goods and materials such as silver using its Mediterranean trade network; and 3) controlling supply markets in the places they colonized. The Phoenicians made huge profits selling high-end luxury items like purple cloth. Cedar from Lebanon, a highly valued building material, was also quite profitable. They also moved large amounts of wine and olive oil. Trading posts eventually grew into colonies. Little is known about the specifics of Phoenician trade: exactly what route they took, and the amount and types of cargo they carried.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art:“Confined to a narrow coastal strip with limited agricultural resources, maritime trade was a natural development. By the late eighth century B.C., the Phoenicians, alongside the Greeks, had founded trading posts around the entire Mediterranean and excavations of many of these centers have added significantly to our understanding of Phoenician culture.

The main natural resources of the Phoenician cities in the eastern Mediterranean were the prized cedars of Lebanon and murex shells used to make the purple dye. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Phoenicians (1500–300 B.C.)", Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004]

The Phoenicians traded with the pharaohs of Egypt and carried King Solomon's gold from Ophir. There are Egyptian records, dating to 3000 B.C., of Lebanese logs being towed from Byblos to Egypt. From 2650 B.C. there is record of 40 ships towing logs. Phoenicia competed with the Greeks and Etruscans and later the Romans. A 2,500-year-old gold plate with Phoenician letters found in Prygu, Italy in 1964 is offered as proof that they traded with the Etruscans by 500 B.C., before the rise of Rome. The majority of the trade between the eastern and western Mediterranean passed through the strategic waterway off Cape Bon, Tunisia, between North Africa and Sicily.

See Separate Article: PHOENICIAN TRADE: COLONIES, PURPLE DYE AND MINING africame.factsanddetails.com

Phoenician Explorers

The Phoenicians were the greatest explorers of the ancient world. They discovered the Atlantic and ventured as far away as Britain and Africa. Punic coins were reportedly found in the Azores. The Phoenicians are said to have sailed around Africa in 610 B.C. Some believe they may have made it to India and even America. The Greek historian Diodorus said they traveled to west to a “an island of considerable size...fruitful, much of it mountainous. Through it flow navigable rivers.”

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Sea traders from Phoenicia and Carthage (a Phoenician colony traditionally founded in 814 B.C.) even ventured beyond the Strait of Gibraltar as far as Britain in search of tin. However, much of our knowledge about the Phoenicians during the Iron Age (1200–500 B.C.) and later is dependent on the Hebrew Bible, Assyrian records, and Greek and Latin authors. For example, according to the Greek historian Herodotus, Phoenician sailors, at the request of the pharaoh Necho II (r. ca. 610–595 B.C.), circumnavigated Africa. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004]

Herodotus wrote around 600 B.C. that Phoenician ships circled Africa to pay homage to the Egyptian Pharaoh Necho II. "The Phoenicians...sailed the southern seas,” he wrote, "whenever autumn came they would put in and sow the land....then, having gathered in the crop, they sailed on, so that after two years had passed, it was in the third that they rounded the Pillars of Hercules and came to Egypt. There they said (what some may believe, though I do not) that in sailing round Libya they had the sun on their right hand [an indication they were in the southern hemisphere].

Classical texts suggest a colony may have been established beyond the Strait of Gibraltar on Cadiz in present-day Spain by 1100 B.C. The oldest archeology remains linked to the Phoenicians however date only to the 8th century B.C. Some archeologist believe a rock painting dated to the 2nd millennium B.C., of stick figures surrounding a ship is of Phoenicians.

In the 5th century B.C. boat launched from Carthage traveled beyond Gibraltar. The Phoenician voyager Himilco who set out looking for tin and an ocean passage to avoid overland routes may have reached Britain. The Carthaginian navigator Hanno may have carried colonists to the Gulf of Guinea, where his logbook described crocodiles, hippopotamuses and "women with shaggy bodies...called Gorillas."

Some modern scientist say the Phoenicians may have reached America based on similarities between Phoenician cultures and cultures in the Americas.

Phoenician Ships

The Phoenicians sailed the most advanced ship in the world during their time. The Greek historian Polybius wrote in the 2nd century B.C. they " were far superior, both in the speed of their ships and the way they built them, and also in the experience and skill of their seamen.” Romans based their boat designs on Phoenician ships that were captured and copied exactly

The Phoenicians traveled in deep-laden "round ships" with horse head bows, a single square sail and ballast stones balanced on green branches. Hulls were lined with brush, which absorbed shocks, and kept the cargo from shifting in the hold. Food such as olive oil and garum fish sauce as well as wine was stored in amphorae. Some ships were outfit with wooden anchors filled with lead. Large cargo-carrying ships were over a 100 feet long. The discover of small 25-foot-longboats indicates they may have used small craft to ferry supplies from large cargo ships to shore.

A 7th-century B.C. relief from the palace of Sennacherib in Nineveh depicts Phoenician ships at sea. Large sea-worthy, Greco-Roman-era war ships such as the 50-oar galleys known as “penteconter” were sheathed in bronze and built to ram other ships. They had two banks of oars and a swan neck poop.

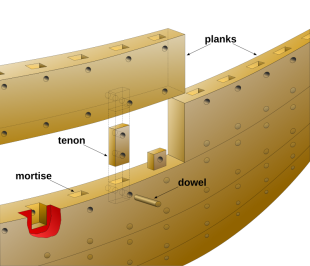

After the discovery of a Phoenician shipwreck off Spain, Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: "For maritime archaeologists, the discovery of a Phoenician wreck offered a rare opportunity to analyze the structure and engineering of a Phoenician ship and discover details about the origin and evolution of ancient ship construction. Polzer says, "My initial interest in finding and excavating a Phoenician shipwreck was very much tied to questions of construction practices, technological changes, and technology transfer between cultures." However, the team found only a one-and-a-half-foot-long wooden plank from the ship's hull. That small surviving fragment did preserve half of a mortise and corresponding tenon peg hole, from which the team could conclude only that the Phoenician ship was constructed using mortise-and-tenon joinery. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

Phoenician Ship Construction

Phoenician ships used mortise-and tenon technology as did the ships of the ancient Greeks and Romans. On ancient Greek and Roman ships the hulls were built first and then strengthened with an internal frame. The practice of building ribs onto the keel and then attaching hull planks to the skeletons did not become commonplace until the Middle Ages. Instead planks in the hull were held together with mortises and tenons (slots and wooden pieces) that were fit together with great skill.

The mortises (slots) were drilled into the planks and spaced from five to 10 inches apart. Adjoining planks had mortise in the same places. Tenons (wooden pieces) were placed in the slots to hold the planks together. Wooden pegs or copper nails were then hammered into the tenons to hold them in place. The fit was so tight that caulking wasn’t needed. The hull was tarred and sheathed in lead primarily as protection from shipworms. The thickness of the planks varied from one inch to four inches. Hulls with thin planks had two layers of planks around the keel.

Phoenician Shipwrecks

For a long time no one was sure what Phoenician boats looked like. One had never been found. Details were gleaned from ships used by cultures that lived at the same times as the Phoenicians.

In 1999, two Phoenicians vessels were located by deep sea robots. Dated at 750 B.C. the vessels were found in 1,000- to 3,000-foot-deep waters off the off the coast of Israel and Egypt near the Mediterranean port of Ashkelon. Each vessel was carrying around 10 tons of wine stored in ceramic jugs called amphorae. One vessel was 58 feet long and the other was 48 feet long. They appeared to have sunk in a storm and landed on the sea floor about a kilometers and half apart. The large one carried about 400 amphorae that held 20 liters each.

The site was located in 1997 by a U.S. Navy research submarine that noticed hundreds of large amphorae, arrayed roughly in the shape of a ship on the sea floor. The site was investigated by the ROV Jason submersible by a research team lead by Bob Ballard. They were the first Iron Age ships found in the Mediterranean The vessels were dated by the distinctive mushroomed-shaped lids of the amphorae which were common between 750 and 700 B.C. The amphorae were in excellent condition. The robots also found stone anchors, crockery for food preparation, a wine decanter and an incense sand.

Two 7th century B.C. Phoenician shipwrecks have been found in the Bay of Mazaron near Cartagena in Spain. Excavations revealed mortise-and -tendon joints, lead from wooden anchors, intact Phoenician knots, amphorae, and millstones use to grind wheat. Another Phoenician ship was pulled from the sea near Kyrenia, Cyprus. It went down in the 4th century B.C. and carried mostly wine jars.

In 2023, Spanish archeologists said they planned to recover a 2,500-year-old Phoenician shipwreck off Mazarron, Spain before a storm destroyed it forever. Reuters reported: The 26-foot-long Mazarron II lies off Playa de la Isla beach under 5.6 feet of crystal-clear Mediterranean water. Carlos de Juan, Archeologist and project leader said: “It is an archeological jewel, which means it is unique. We do not have in our latitudes wreckages of the Phoenician culture that preserve their naval structure. Therefore, we have just this one. It is a piece that deserves special treatment. It has been declared an asset of 'cultural interest.'” [Source: Reuters Videos July 1, 2023]

Nine technicians underwent 560 hours of scuba diving over more than two weeks to record all the cracks and fissures in the ship The boat had to be extracted piece by piece and reassembled onshore “The photographs show us a puzzle that is already assembled, we see the fusiform shape of a not very large coastal vessel, about eight meters long and it gives the impression that we have only one piece. But this is not the reality of archeology. Archeological wood, after spending so much time underwater, in this case over 2,500 years, loses its physical and chemical properties and begins to crack.

Phoenician Shipwreck Off Of Spain

Phoenician boat Between 2007 and 2011, a Phoenician shipwreck was excavated at Bajo de la Campana, 30 kilometers northeast of Cartagena in southeast Spain by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA). The first Phoenician shipwreck to be excavated by archaeologists, the wreck at Bajo de la Campana, a submerged rock reef off Spain’s coast near Cartagena, dates to some 2,700 years ago. The ship ran aground and spilled its cargo onto the seabed, where a number of finds ended up clustered in a sea cave. [Source: James P. Delgado, Archaeology magazine]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Toward the end of the seventh century B.C. ., a Phoenician ship laden with cargo encountered catastrophe off the Iberian coast. The vessel had been sailing a few miles offshore when rough weather drove it onto a shallow reef. Although their homeland lay nearly2,500miles to the east, the crew was in familiar waters, as Phoenician sailors had been trading and living along the Iberian coauthor almost four centuries. The treacherous rock outcropping, known today as Bajo de la Campana,was nonetheless unavoidable and punched a hole in the ship's hull, sending the vessel and at least for tons of cargo to the seafloor.[Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

The Bajo de la Campana reef is a cruel bit of nature that is responsible for a veritable graveyard of wrecks, both modern and ancient. Located two-and-a-half miles offshore, around20miles northeast of Cartagena, Spain, today the Bajo de la Campana rock formation rises up suddenly from a depth of50feet to within three feet of the surface, although in antiquity it protruded above the water.

For researchers ,this single ship stands as a microcosm of everything that was described in historical accounts of the Phoenician talent for maritime trade and their inspired seamanship. Archaeological evidence now shows that this single vessel was transporting cargo that originated from more than a dozen far-flung places: elephant tusks from North Africa, tin from northwest Iberia, copper from throughout the Mediterranean, amber from the Baltic, and ceramics from local Phoenician workshops in southern Iberia, North Africa, and the Near East. It is no wonder that the ancient cultures the Phoenicians encountered often referred to them as the "princes of the sea."

Phoenician Shipwreck Archaeology

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: But while the accolades heaped upon them in ancient written sources have helped inform an understanding of Phoenician culture, tangible archaeological details about their voyages, ships, and cargoes have long remained sparse. "Phoenician archaeology in general lags [behind] that of the ancient Greeks and Romans," says maritime archaeologist Mark Polzer of Flinders university in Australia. "What is missing is evidence from their ships and sea voyages—in other words, shipwrecks. No attempt to truly understand the Phoenicians and their reach will be complete without them." Now,2,600yearslater, extensive excavations of the Bajo de la Campana wreck site are helping archaeologists retrace the ship's fateful last voyage—and study of its enormous and varied cargo is providing important insights into the most sophisticated trade network of its time. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

Polzer says, "Before our excavation at Bajo de la Campana, no wreck of a seagoing Phoenician ship had been found and explored."Polzer served as co-director of the Bajo de la Campana project, led by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology and the Spanish Ministry of culture, which, between 2007 and 2011, conducted more than 4,000 dives at the wreck. The site, he believes, has enormous potential to provide an unparalleled glimpse of Phoenician commercial activity in the west—specifically colonial trade along the coast of Iberia—carried out on an impressive scale. The preservation of the Bajo de la Campana shipwreck is itself astonishing, as the site had been exploited by both recreational and commercial divers for more than50years.

In the1950s, salvage divers seeking scrap metal from modern shipwrecks began to explore the site. They exposed the first ancient artifacts, and, over the next few decades, the site was frequently looted by sport divers. At one point, it was even used by the Spanish navy for underwater demolition training. However, modern interventions may have inadvertently preserved the wreck site. In the early twentieth century, the Spanish government decided to blow the top off the rocks to reduce the risks for passing ships. "The rock debris from these explosions fell mostly onto the wreck site below, damaging most of the archaeological material lying exposed on the surface," says Polzer, "but likely also protecting the site from looting and further damage.

Shipwreck Found in Spain Yields Clues About Phoenician Trade

James P. Delgado wrote in Archaeology magazine:“Under the direction of Mark Polzer and Juan Piñedo Reyes, archaeologists recovered fragments of the hull along with a large number of ceramic and bronze artifacts, as well as pine nuts, amber, elephant tusks, and lead ore. The tusks include examples engraved with the Punic names of their owners. The Bajo de la Campana ship was likely a trader from the Eastern Mediterranean that journeyed west, at least as far as today’s Cadiz, in its quest for goods. Most were raw commodities, such as the ivory and lead ore, which the ship’s crew had acquired through trade with the indigenous people of this part of Spain. [Source: James P. Delgado, Archaeology magazine]

“The wreck at Bajo de la Campana underwent analysis by Polzer and Piñedo at Cartagena’s Museum of Underwater Archaeology and yielded evidence of a wide maritime trade network. The Bajo de la Campana ship demonstrates, like the earlier Cape Gelidonya and Uluburun ships, that commerce by sea linked cultures and helped build trading empires—in this case, that of the Phoenicians. In time, they dominated the Western Mediterranean, established port cities and colonies such as Cartago Nuovo (today’s Cartagena), and ultimately clashed with the growing power of Rome.”

See Separate Article: PHOENICIAN TRADE: COLONIES, PURPLE DYE AND MINING africame.factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024