PHOENICIAN TRADE

Punic ostrich egg from Villaricos Pliny once wrote, the "Phoenicians invented trade." Phoenicians engaged in three types of trading activities; 1) exporting material, namely cedar, from their traditional homeland in Lebanon; 2) earning transport and middleman fees from shipping goods and materials such as silver using its Mediterranean trade network; and 3) controlling supply markets in the places they colonized. The Phoenicians made huge profits selling high-end luxury items like purple cloth. Cedar from Lebanon, a highly valued building material, was also quite profitable. They also moved large amounts of wine and olive oil. Trading posts eventually grew into colonies.

Little is known about the specifics of Phoenician trade: exactly what route they took, and the amount and types of cargo they carried.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art:“Confined to a narrow coastal strip with limited agricultural resources, maritime trade was a natural development. By the late eighth century B.C., the Phoenicians, alongside the Greeks, had founded trading posts around the entire Mediterranean and excavations of many of these centers have added significantly to our understanding of Phoenician culture.

The main natural resources of the Phoenician cities in the eastern Mediterranean were the prized cedars of Lebanon and murex shells used to make the purple dye. [Source: Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Phoenicians (1500–300 B.C.)", Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004]

The Phoenicians traded with the pharaohs of Egypt and carried King Solomon's gold from Ophir. There are Egyptian records, dating to 3000 B.C., of Lebanese logs being towed from Byblos to Egypt. From 2650 B.C. there is record of 40 ships towing logs. Phoenicia competed with the Greeks and Etruscans and later the Romans. A 2,500-year-old gold plate with Phoenician letters found in Prygu, Italy in 1964 is offered as proof that they traded with the Etruscans by 500 B.C., before the rise of Rome. The majority of the trade between the eastern and western Mediterranean passed through the strategic waterway off Cape Bon, Tunisia, between North Africa and Sicily.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Phoenicians: The Purple Empire of the Ancient World ” by Gerhard Herm (1973) Amazon.com;

“Phoenicians and the Making of the Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians and the West” by María Eugenia Aubet (1993) Amazon.com;

“The Lost Colonies of Ancient America: A Comprehensive Guide to the Pre-Columbian Visitors Who Really Discovered America” by Frank Collin) Amazon.com;

“Out of Arabia: Phoenicians, Arabs, and the Discovery of Europe” by Warwick Ball (2009) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Secrets: Exploring the Ancient Mediterranean” by Sanford Holst (2011) Amazon.com;

“Phoenicians: Lebanon's Epic Heritage” by Sanford Holst (2005) Amazon.com;

“Phoenician Civilization: A History from Beginning to End” by History Hourly (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Phoenicians: Lost Civilizations” by Vadim Jigoulov (2022) Amazon.com;

“In Search of the Phoenicians” by Josephine Quinn (2017) Amazon.com;

"The Phoenicians" by Donald Harden Amazon.com;

"Phoenicians" by Glenn Markoe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000) Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean” by Carolina López-Ruiz, Brian R. Doak (2019) Amazon.com;

“Carthage Must be Destroyed: The Rise and Fall of an Ancient Mediterranean Civilization” by Richard Miles (2010) Amazon.com;

Phoenician Traded Goods

The Phoenicians traded purple cloth, glass trinkets, perfumed ointments, and fish. They were the first to trade glass items at a large scale. Around the 6th century B.C. the “core glass method” of glass making from Mesopotamia and Egypt was revived under the influence of Greek ceramics makers in Phoenicia in the eastern Mediterranean and then was widely traded by Phoenician merchants. During the Hellenistic period, high quality pieces were created using a variety of techniques, including the cast glass and mosaic glass.

The Phoenicians grew rich selling timber from the mountains of Lebanon. The timber was used for making ships and columns for houses and temples. Neither Egypt nor Mesopotamia had good sources of wood and civilizations all over the Middle East looked to Lebanon for timber. The Phoenicians traded timber for papyrus and linen from Egypt, copper ingots from Cyprus, Nubian gold and slaves, jars with grain and wine, silver, monkeys, precious stones, hides, ivory and elephants tusks from Africa.

Cedar was perhaps the most valuable source of income for the Phoenicians. An alabaster relief from the Assyrian King Sargon II, dated to 700 B.C., shows the transportation of logs by ship. The relief shows cedars logs being loaded on small rivercraft called “ hippos” that carried and pulled the logs. Papyrus was the main item from Egypt traded for timber. From Byblos papyrus was distributed to other places.

Purple Dye — Worth More Than Gold

Sara Toth Stub wrote in Archaeology magazine: “In the ancient world, textiles colored with purple dye made from murex shells were worth their weight in gold and were often listed along with precious metals in trade and tax records. These textiles bestowed prestige, royal status, and even sacredness on those who wore or were buried in them. The dye is referenced in the Hebrew Bible, in which its purple and blue colors are called argaman and tekhelet, respectively, and instructions are given to hang strings dyed in the tekhelet shade from the corners of garments. Part of what made murex dye so valuable was that its colors remain brilliant. For example, 2,000-year-old pieces of murex-dyed wool found in caves near the Dead Sea are still vibrant today. [Source: Sara Toth Stub, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

In the twelfth century B.C., according to contemporaneous administrative documents, the kingdom of Ugarit in northern Syria paid tribute to the occupying Hittites in the form of purple wool. A ninth-century B.C. inscription attributed to the Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III records that he received purple wool as an incentive to form an alliance with the seafaring traders known as the Phoenicians. Purple wool is also listed among the war spoils taken by Tiglath-Pileser, the Neo-Assyrian king who conquered ancient Syria and Palestine in the eighth century B.C. Much later in history, the dye was responsible for the distinctive purple togas worn by high officials of the Roman Empire. “We are talking about one of the most important industries in the Iron Age and across the ancient world,” says Shalvi. “Now we finally know what would bring people to such a place.”

Snails of the Hexaplex trunculus species are one of three types of snails used to make murex dye.Some aspects of the dye-making process remain unknown, but it involved breaking open sea snail shells, removing the hypobranchial gland, and harvesting the clear fluid inside. In a process taking several days, this liquid was then heated and dissolved in an alkaline solution believed to have been made from urine or certain plants. This eventually produced a yellow fluid, into which yarn was dipped. Hexaplex trunculus provides a greater quantity of dye-making liquid than the other two color-producing species, Bolinus brandaris and Stramonita haemastoma, and is found widely in the Mediterranean. [Source: Sara Toth Stub, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

Upon being exposed to light or oxygen, the yarn turned a rich hue. At least three species of murex sea snails produce the color-changing liquid, and the dye’s final shade depends on the species used, the length of exposure to the elements, and the type of fabric. “It’s more of an art than a science,” says Julie Mendelsohn, a textile expert at the University of Haifa. It takes thousands of snails to produce just a small amount of the dye, and the Talmud, as well as Greek and Roman historians, describe the dye-making process as messy, malodorous, and tedious. “The small fish are crushed alive, together with the shells, upon which they eject this secretion,” Pliny the Elder writes in his first-century A.D. Natural History. “The smell of it is offensive.”

Did Phoenicians Invent Dye Production

For more than 2,000 years, historical sources have credited the discovery of purple-dye production to the Phoenicians. Sara Toth Stub wrote in Archaeology magazine: According to a second-century A.D. account from the Greek historian Julius Pollux, a dog belonging to the Phoenician king Heracles of Tyre accidentally discovered the dye’s source by biting on a seashell. In fact, the word “Phoenician,” a moniker first bestowed by the Greeks, means purple. [Source: Sara Toth Stub, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

Despite the long-standing association between the Phoenicians and murex dye, however, scholars believe they probably were not the first to develop it. Instead, evidence increasingly points to the island of Crete as its origin. There, from about 3000 B.C. until the mid-fifteenth century B.C., the Minoans established extensive maritime trade networks around the Aegean. Ancient tablets from the Minoan palace at Knossos refer to the royal use of purple textiles.

In 2016, chemical analysis of residue in stone vats and vessels from a Minoan-era dye installation on the nearby island of Pefka identified biomarkers of murex snails, along with lanolin, which was used to prepare raw wool for dyeing. This indicates that as far back as 1800 B.C. — at least 300 years before the rise of the Phoenicians — people there colored textiles using murex dye. Andrew Koh, an archaeologist and historian at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who conducted residue analysis of pottery and stone dyeing installations from Pefka, says the rugged shorelines of Crete and nearby islands were especially suitable for murex snails, which thrive along shallow, rocky coastlines. “In terms of pure numbers [of snails] and ecological conditions,” he says, “chances are this industry was invented in Greece.”

“Other cultures, including the Phoenicians, eventually learned of the murex dyeing technique through trade relations, Koh suggests, and he and Gilboa agree that the Phoenicians likely improved on the Minoans’ techniques and expanded the dye’s reach. Says Koh, “It’s clear that by the eighth century, the Phoenicians have the hold on this industry.”

Purple Dye Textile Center in Israel

Not far from Mount Carmel and the industrial port city of Haifa on Israel’s Mediterranean coast is a site called Tel Shikmona in Hebrew, or Tell es Samak, “Hill of the Fish,” in Arabic. Numerous rocks dot the shallow water, which is navigable only by the smallest of boats., curious. Archaeologists for a long time couldn’t understand why, beginning in the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1200 B.C.), and continuing more than 1,000 years into the Byzantine period, people would settle there. [Source: Sara Toth Stub, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

Sara Toth Stub wrote in Archaeology magazine: Among the stored artifacts and original handwritten documents from digs at Tel Shikmona in the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists Golan Shalvi and Ayelet Gilboa, both of the University of Haifa, have found dozens of pottery vessels and sherds covered with purple and blue stains, evidence that people were producing a coveted dye using liquid extracted from the glands of murex sea snails at the site. Until now, such evidence from the Bronze and Iron Ages has been limited to scattered pieces of stained pottery and heaps of murex snail shells found at several sites in modern-day Lebanon and Israel.

“In 2016, Shalvi and Gilboa began to study finds found by Israeli archaeologist Joseph Elgavish, who first excavated the site in the 1960s. They uncovered substantial evidence of a Phoenician presence at Tel Shikmona, including figurines and pottery, and enough purple-stained sherds to determine that it had been a major murex dyeing installation at various times between the tenth and seventh centuries B.C. Naama Sukenik of the Israel Antiquities Authority, together with researchers from Bar-Ilan University, has analyzed residue on the Tel Shikmona sherds and concluded that the stains were made by the Hexaplex trunculus snail. Soot marks have also been identified on the outer layers of the stained sherds discovered at Tel Shikmona, indicating that the thick-walled jars were heated as part of the dye-making process. Sukenik says the vessels likely had narrow openings to control the amount of air the yarn was exposed to during the process.

“The storeroom cache contained an additional surprise: more than 200 loom weights and 60 spindle whorls, disc-shaped stone objects that speed up the process of hand-spinning raw wool. These artifacts indicate that a substantial workforce at the site was making wool into yarn, which was then dyed purple. “This is really a large number of spindle whorls,” Mendelsohn says, adding that the high quality of some of the objects, and the fact they may have been made from stone imported from Cyprus or Greece, suggests that those who used them were skilled professionals possibly connected with or originally from these places, which had long traditions of murex dyeing. “It seems Tel Shikmona wasn’t a residential site at all, at least not at this time,” says Shalvi. “It was a factory.” He adds that the fact that the settlement was surrounded by a defensive wall underscores how valuable the dye industry was.

“Murex dyeing at Tel Shikmona appears to have ceased for a short time toward the end of the eighth century B.C. Archaeological layers from that period uncovered by Elgavish and analyzed by Shalvi contain no purple-stained vessels or sherds. This suggests that the Israelites may have taken Tel Shikmona over as part of their broader northern expansion, Gilboa says, ushering in a period of political instability and economic uncertainty that could have disrupted the dye industry. She adds that it’s quite possible that the Israelites did not use murex for dyeing.

Phoenician Metallurgy and Gold, Silver and Tin Trade

The Phoenicians traded for iron from mined in Ebla, gold from Andulusia and tin from Cornwall. By the 9th century B.C. they established a whole series of communities along the southern coast of Spain to move metals and minerals mined in Iberian mines.

The Phoenicians monopolizes the tin trade. Tin was needed for bronze. It was carried from Britain to Cadiz in Spain and carried overland to Mediterranean ports. Silver that came from Spain may have gone through the Straits of Gibralter. The presence of ivory tusks indicates they probably traded ivory too.

The Phoenician usually landed and stayed in a defensible position until inhabitants brought enough gold or other valuables to trade and then withdrew. The traders would come ashore and examine the gold. If there was enough they would take it and leave their trading goods. If not they would go back to their boats and leave the gold behind and wait for a better offer. Neither side agrees until they are satisfied," wrote Herodotus, "The Carthaginians don't touch the gold until it equals the value of their goods, nor the natives their goods till the ships have taken the gold."

CT scans of ancient bellows unearthed in Carthage reveled sophisticated intake valves that regulated airflow in hearths to raise the temperature in iron-making furnaces. The Carthaginians strengthened their metals with calcium, using a metallurgical technology similar to the Bessemer process, which was not invented until the 19th century. The source of the calcium was the same murex snails that were the source of the valuable purple dye.

Trade Between the Ancient Greeks and Phoenicians

After the power of the Phoenicians declined, the ancient Greeks became the main traders and economic power in the Mediterranean. On the relationship between the Greeks and Phoenicians, Herodotus wrote in “Histories,” Book I, '1-2 (480 B.C.): “The Phoenicians, who had formerly dwelt on the shores of the Persian Gulf, having migrated to the Mediterranean and settled in the parts which they now inhabit, began at once, they say, to adventure on long voyages, freighting their vessels with the wares of Egypt and Assyria. They landed at many places on the coast, and among the rest at Argos, which was then pre-eminent above all the states included now under the common name of Hellas. [Source: Source: Herodotus, “Histories”, translated by George Rawlinson, New York: Dutton & Co., 1862]

“Here they exposed their merchandise, and traded with the natives for five or six days; at the end of this time, when almost everything was sold, there came down to the beach a number of women, and among them the daughter of the king, who was, they say, agreeing in this with the Hellenes, Io, the child of Inachus. The women were standing by the stern of the ship intent upon their purchases, when the Phoenicians, with a general shout, rushed upon them. The greater part made their escape, but some were seized and carried off. Io herself was among the captives. The Phoenicians put the women on board their vessel, and set sail for Egypt. Thus did Io pass into Egypt, and thus commenced the series of outrages. . . .At a later period, certain Greeks, with whose name they are unacquainted, but who would probably be Cretans, made a landing at Tyre, on the Phoenician coast, and bore off the king's daughter, Europa. In this they only retaliated. The Cretans say that it was not them who did this act, but, rather, Zeus, enamored of the fair Europa, who disguised himself as a bull, gained the maiden's affections, and thence carried her off to Crete, where she bore three sons by Zeus: Sarpedon, Rhadamanthys, and Minos, later king of all Crete.”

In “Histories” Book V, '57-59, Herodotus wrote: “Now the Gephyraean clan, claim to have come at first from Eretria, but my own enquiry shows that they were among the Phoenicians who came with Cadmus to the country now called Boeotia. In that country the lands of Tanagra were allotted to them, and this is where they settled. The Cadmeans had first been expelled from there by the Argives, and these Gephyraeans were forced to go to Athens after being expelled in turn by the Boeotians. The Athenians received them as citizens of their own on set terms. These Phoenicians who came with Cadmus and of whom the Gephyraeans were a part brought with them to Hellas, among many other kinds of learning, the alphabet, which had been unknown before this, I think, to the Greeks. As time went on the sound and the form of the letters were changed. At this time the Greeks who were settled around them were for the most part Ionians, and after being taught the letters by the Phoenicians, they used them with a few changes of form. In so doing, they gave to these characters the name of Phoenician. I have myself seen Cadmean writing in the temple of Ismenian Apollo at Boeotian Thebes engraved on certain tripods and for the most part looking like Ionian letters.

Phoenician cedar trade

Phoenician Colonies

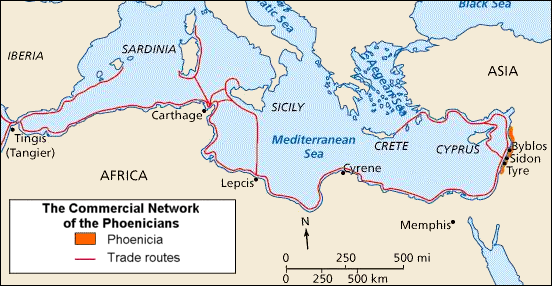

The Phoenicians are credited with creating the first colonies and pioneering the concept of trading consumer products for raw materials on a large scale. The Phoenicians began migrated to the eastern Mediterranean around 1200 B.C. beginning with Cyprus. They expanded when the Minoans, who dominated trade in the Mediterranean, were overthrown by Mycenaeans between 1400 and 1200 B.C. The Phoenicians set up colonies in northern Israel, and spread around the east and west of the Mediterranean, setting up settlements in Tunisia, Sicily and Sardinia, Their trading centers in the eastern Mediterranean were connected to those in the east by a set of ingenious way stations.

According to Archaeology magazine: In the opening centuries of the first millennium B.C., The Phoenicians established such commercial centers and colonies all over the Mediterranean: Cerro de Villar, Los Toscanos, and La Fonteta in Spain, Sa Caleta in Ibiza, Sulcis in Sardinia, Utica and Carthage in Tunisia, Motya in Sicily, Malta, and Kition in cyprus. From Gadir in the Atlantic to Tyre in the Levant, these sites and many others formed the commercial links that provided the essential infrastructure enabling the Phoenicians to construct their unparalleled Mediterranean-wide trade network. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

About 1.6 kilometers (a mile) off Gozo Island in Malta, in 400 feet of water, researchers have found and examined what might be the oldest shipwreck in the central Mediterranean — a 50-foot-long trading vessel packed with 50 diverse amphoras and 20 grinding stones. The cargo dates to around 700 B.C., when Phoenicians traded across the Mediterranean, and Malta represented an important stop on long sea voyages. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2014]

Riotinto Mines in Spain

For 5,000 years what today are known as the Riotinto Mines in southwestern Spain produced wealth that sustained civilizations, riches that created cash economies and pollution that spread around the globe. Barry Yeoman wrote in Archaeology Magazine, “Riotinto is part of the Iberian Pyrite Belt, a mineral deposit that stretches from Spain into Portugal. It is one of the largest known mining complexes in the ancient world. Starting as a surface operation focused on copper minerals, it eventually became an industrial-scale enterprise until it finally closed in 2001 amid falling copper prices. [Source: Barry Yeoman, Archaeology Magazine, September-October 2010]

"The name Riotinto has something of a magical connotation," wrote University of Sevilla archaeologists Antonio Blanco Freijeiro and José María Luzón Nogué in 1969. "It has been called the geologist's paradise because at almost no other place on the earth has nature exposed in one spot such richness and variety of minerals." Visiting in the late 1980s, archaeologist Lynn Willies of England's Peak District Mining Museum described it as a landscape turned upside-down: "The hills have literally been turned into valleys, and the valleys made into hills." Even more striking than the topography is the landscape's color palette: crimsons, blue-grays, and ochres, which give the place an otherworldly feel. Naturally dissolving iron, a process believed to predate the mines, has dyed the acidic river "tinto," or wine-colored. So otherworldly is Riotinto that NASA has used robots to drill its soil-practice for the search for underground life on Mars.

Local folklore places King Solomon's mines at Riotinto, though a more factual history has been more difficult to write. "Its birth is shrouded in the mists of antiquity," wrote William Giles Nash, a Rio Tinto Company employee, in 1904. Archaeologists now know that the area's Copper Age inhabitants were extracting malachite and azurite, two copper-rich minerals, during the third millennium B.C. Inside Riotinto's museum is a 5,000-year-old stone hammer found in one of the mines during the 1980s. These hammers were used to cut trenches in the slate outcroppings-the earliest form of mining at the site.

Phoenician trade

Riotinto Mines Under the Phoenicians

Barry Yeoman wrote in Archaeology Magazine, “The Phoenicians arrived in Spain around 1100 B.C.-their ships filled with ceramics, jewelry, and textiles for trading-and moved inland during the 9th century B.C.” "They didn't bring weapons," says Thomas Schattner, a professor of classical archaeology at Germany's University of Giessen. "They walked in, they exchanged goods with the indigenous people, and they were received." There is no archeological evidence of hostile attacks, Schattner says, which lends credence to the written accounts of peaceful trading. [Source: Barry Yeoman, Archaeology Magazine, September-October 2010]

At Riotinto, the Phoenicians found the silver and copper mines run by an indigenous people called the Tartessians. Even after the foreigners' arrival, the mining operations remained in local hands-though the amount of Phoenician influence remains a point of contention. "None," says Delgado, dismissing those who believe, in his words, that "without the arrival of foreigners, the indigenous people would still be like Adam and Eve." He argues that that only a few Phoenicians lived in the area, where they served as commercial agents. Schattner calls that answer "one-dimensional," noting that both written evidence and the size of the slag heaps show that silver production spiked at mines like Riotinto after the Phoenicians' arrival. Delgado contends this is solely because of higher demand; Schattner disagrees. Among the finds at Riotinto, Schattner says, are rectangular clay nozzles that had been attached to leather bellows, which pumped air into smelting furnaces. "The introduction of bellows is one of the most important contributions of Phoenician technology," he says. "It permits bigger ovens, higher temperatures, more successful melting, and much bigger amounts of metal. It's the beginning of industrial production. You would not obtain this amount of silver by using the old-fashioned technology."

Beyond mining, the Phoenician arrival sparked "a kind of globalization," says Schattner. In the seventh century B.C., the eastern Mediterranean was shifting toward a coin-based economy, and the Phoenicians needed silver to decorate their temples and pay their debts to the Assyrian empire. Silver-which was shipped off the Iberian Peninsula in bars or ingots, according to shipwreck evidence-was the perfect currency, he says: rare enough for coins to have value but common enough for many people to participate in the economy. "Without the silver mines of southern Spain, the development of money would have been quite different-based on a medium that was less ideal," Schattner says.

The globalization was cultural, too, Schattner argues. He has been excavating at Castro Cerquillo, a Phoenician-era village outside the Tharsis mines, 40 miles west of Riotinto. There, he says, "we made the astonishing observation that the new settlements of the indigenous people are being built in an Eastern manner, with orthogonal streets like New York, at right angles, making blocks-a very modern manner for that time." While the Phoenicians were extractors of wealth, Schattner says, they were also "distributors of ideas-for cities, for material culture, for houses, for living."

Demand for Silver Spurs Phoenician Trade with Spain — and Growth in the Roman Empire

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: During this period, there was widespread demand for precious metals, especially silver, which was the preferred currency of the day. In addition, Phoenicians owed their neighboring Assyrians large quantities of silver in annual tribute. This demand for silver would prove pivotal to Phoenician expansion. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

The best source of silver, as yet untapped, was located thousands of miles away, in southern Iberia. Although in antiquity this meant a three-month-long journey, the pursuit of metals compelled Phoenicians (especially those representing Tyre) to sail westward. "The conventional explanation, which by and large still stands, is that they were looking for minerals—silver in the first place—and mining resources in the south of Spain," says van Dommelen. Iberia, especially the Rio Tinto region of southwestern Spain, turned out to be one of the ancient world's richest sources of metals.

By the end of the tenth century B.C., Phoenician merchants were frequenting this area and establishing commercial relationships with the indigenous Tartessian culture that controlled the Iberian metal trade. In doing so, they created a vast long-distance trade circuit that eventually spanned not only the entire Mediterranean Sea, but extended into the Atlantic as well. Van Dommelen says, "The east-west connection in the tenth century B.C. ., from Tyre and Sidon to Iberia and past the Pillars of Hercules, is something that had never been done before." As Phoenician traders continued to sail westward more and more frequently, they began to establish permanent colonies throughout the central and western Mediterranean.

According to Archaeology magazine: After defeating Hannibal and Carthage in the Second Punic War (218–201 B.C.), Rome found itself the dominant power in the western Mediterranean. While it may seem obvious that Rome’s prospects would rise, having vanquished its chief military, economic, and political rival, a new study led by Katrin Westner of Goethe University suggests that it was the massive influx of Iberian-mined silver into the Roman economy that fueled its unprecedented expansion. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2017]

Researchers analyzed the elemental composition and lead isotope signature of 70 Roman coins issued between 310 and 101 B.C. in order to determine the source of the silver ore. The results show that in the decades before the Second Punic War, Roman silver originated mostly from Aegean sources and Greek colonies in Magna Graecia. However, coins issued after the war had a different isotope signature, one that closely matched known metal sources from the Iberian Peninsula. The silver mines of southern Spain were an enormous economic resource once exclusively controlled by Carthage, but which Rome appropriated following its victory. This newly acquired reserve, combined with Carthaginian silver acquired as war booty and indemnities paid by Carthage, brought an extraordinary amount of capital into Rome’s coffers.

Phoenician Colonies in Spain

The Phoenicians sailed into Atlantic and set up a colony in present-day Cadiz, Spain on the Atlantic Ocean. In the 1st century B.C., Diodorus of Sicily wrote: “They planted many colonies throughout Libya...amassed great wealth and essayed to voyage beyond the Pillars of Hercules into the sea men call the ocean.” Phoenician statues have been found all over Spain.The Phoenicians set up outposts on Sardinia and Ibiza in Spain. This led some scholars to the conclusion they frequently engaged in open sea travel and didn’t just hug the shores. Carthage expanded into Spain between 237 and 218 B.C. in part to prepare for an invasion of Rome.

The most important Phoenician settlement in Iberia was Gadir (modern-day Cádiz), located west of the Strait of Gibraltar in southwestern Spain. Archaeological excavations have revealed that a community of Phoenicians was living there from at least the late ninth century B.C.

According to Archaeology magazine: When they settled in Iberia, they appear to have been wary of their new neighbors. To take precautions, they dug an enormous moat around their colony at Cabezo Pequeño del Estaño, which they established in the 8th or 9th century B.C. Reaching a depth of almost 10 feet and 26 feet across, this defensive feature would have been daunting to potential attackers. [Source: Archaeology Magazine, April 2021]

Shipwreck Found in Spain Yields Clues About Phoenician Trade

Between 2007 and 2011, a Phoenician shipwreck was excavated at Bajo de la Campana, 30 kilometers northeast of Cartagena in southeast Spain by the Institute of Nautical Archaeology (INA). The first Phoenician shipwreck to be excavated by archaeologists, the wreck at Bajo de la Campana, a submerged rock reef off Spain’s coast near Cartagena, dates to some 2,700 years ago. The ship ran aground and spilled its cargo onto the seabed, where a number of finds ended up clustered in a sea cave. [Source: James P. Delgado, Archaeology magazine]

James P. Delgado wrote in Archaeology magazine:“Under the direction of Mark Polzer and Juan Piñedo Reyes, archaeologists recovered fragments of the hull along with a large number of ceramic and bronze artifacts, as well as pine nuts, amber, elephant tusks, and lead ore. The tusks include examples engraved with the Punic names of their owners. The Bajo de la Campana ship was likely a trader from the Eastern Mediterranean that journeyed west, at least as far as today’s Cadiz, in its quest for goods. Most were raw commodities, such as the ivory and lead ore, which the ship’s crew had acquired through trade with the indigenous people of this part of Spain. [Source: James P. Delgado, Archaeology magazine]

“The wreck at Bajo de la Campana underwent analysis by Polzer and Piñedo at Cartagena’s Museum of Underwater Archaeology and yielded evidence of a wide maritime trade network. The Bajo de la Campana ship demonstrates, like the earlier Cape Gelidonya and Uluburun ships, that commerce by sea linked cultures and helped build trading empires—in this case, that of the Phoenicians. In time, they dominated the Western Mediterranean, established port cities and colonies such as Cartago Nuovo (today’s Cartagena), and ultimately clashed with the growing power of Rome.”

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: While not finding more of the ship itself was somewhat of a disappointment, archaeologists soon realized that buried beneath the boulders and thick sea grass, much of the ship’s cargo still remained. In their initial survey of the site, the team recovered an assortment of fascinating material that suggested that the Bajo de la Campana site had the potential to be the most significant Phoenician maritime wreck to date. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

"A shipwreck site, as opposed to other archaeological contexts, represents a unique study opportunity," says Polzer. "It preserves an assemblage of material from one specific moment in time."Terrestrial sites, he says, often fall short of being able to provide the same level of detail. Amazingly, there was a lot left to study despite the fact that the ship’s contents were strewn across 4,300 square feet of seafloor, having been buffeted by currents and storms for the last 26 centuries. Hundreds of artifacts were salvaged over five seasons, comprising the most substantial cache of evidence ever retrieved from an ancient Phoenician merchant ship.

"While I was surprised by how much material remained," says Polzer, "I was even more surprised by the variety that we found and the number of unique items we recovered."The Bajo de la Campana ship’s artifacts are allowing researchers to distinguish between types and scopes of trade and to identify spheres of procurement, production, and exchange. In the largest sense, Polzer says, the discovery and analysis of this wreck can reveal the nature of Phoenician trade, colonization, and settlement development, all of which have been only partially understood.

Phoenician Trading Ship Activity

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: The Bajo de la Campana ship, before it met its and, had been sailing off the most densely settled Phoenician territory in the western Mediterranean. From Gadir in the southwest to La Fonteta in the east, the Iberian coast, especially the modern regions of Málaga and Granada, was dotted with Phoenician sites. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

According to Polzer, the Bajo de la Campana ship likely stopped at various ports along this coast during its final journey, specifically Cero de Villar and Abdera, where the crew off-loaded goods and acquired new cargo. Its wreckage provides the best insight archaeologists have so far into what a Phoenician merchant ship was actually transporting during a critical period in Mediterranean history. Polzer says, "It sank at the height of Phoenician colonial and commercial activity in the region, just prior to the fall of Tyre [to the Babylonians back east, and the subsequent collapse of the socioeconomic system in Iberia."

What excavations have revealed is that the Bajo de la Campana ship's extensive and diverse cargo was destined for different markets. Some products were intended for trade and exchange with local Iberians, while others were headed to Phoenician workshops along the coast and communities farther east. These goods made their way on board from a variety of distant places. Phoenician traders are believed to have routinely exchanged products such as wine and olive oil, as well as more luxurious items such as perfume jars, decorated ivories, and ornate bronze vessels for the much-sought-after Iberian metal ore.

Trade Goods Found on Phoenician-Spanish Shipwreck

More than 50 elephant tusks were been found at the site, including 11 that bear Phoenician religious inscriptions. Other items found included ceramic amphora,, a limestone altar, bronze and lead balance weights, wine dipper, copper ingots, alabaster jar fragments, a wooden comb and an amber-bronze incense burner stand Amphora served as the ship's ceramic storage containers, The variety of kinds and sizes are evidence of the enormous variety of goods traded by the Phoenicians. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

Jason Urbanus wrote in Archaeology magazine: Phoenician-made products from the east were in great demand among native Iberian communities, especially the upper classes, and exotic goods were often given to high-ranking Iberian officials to maintain good relations and secure ongoing economic partnerships. The project was able to recover from the wreck a combination of luxury and common goods, as well as both unprocessed commodities and manufactured items. The archaeologists, observing stylistic nuances and using technology, have been able to trace many of the objects to specific locations around the Mediterranean and Atlantic. Large quantities of metal—mainly lead, tin, and copper—were apparently on board.

Archaeologists collected over a ton of raw galena (lead ore) nuggets in addition to more than170 tin and copper ingots. Isotopic analysis of these minerals indicates that the ship's cargo of metals was mined from many geological sources. The lead came from mines in southeastern Spain and the tin from the far northwest. The copper in the ingots was mined from at least eight different regions, ranging from southern Iberia to Sardinia and Cyprus. Polzer believes that these raw minerals may have been destined for La Fonteta, a site 25 miles to the north of the wreck site, where archaeological excavations have revealed an active Phoenician metalworking industry. Every category of artifact found amid the wreckage points to a different aspect of the Phoenician trade network.

The enormous quantities of ceramics discovered attest to the broad range of containers the ship carried, from large storage vessels to elegant cosmetic jars. The ship's distinctive typesof transport amphoras were manufactured both in local Phoenician workshops in Iberia and in colonial centers in the central Mediterranean. The amphoras likely contained Phoenician agricultural products to be traded to local Iberians. Hundreds of other ceramic vessels, both fragmentary and intact, included Phoenician tripod mortars, plates, bowls, perfume bottles, jugs, urns, and pitchers.

An assortment of mundane items that may have been used by the crew, such as balance weights, whetstones, oil lamps, resin for flavoring wine, and even pitch for waterproofing the ship, were also found. These are all helping researchers reconstruct everyday aspects of a Phoenician merchant ship. Polzer says, "The benefit, from an archaeological standpoint, of shipwrecking events, as with other catastrophic occurrences, is that they preserve indicators of normal, daily life."

Were Many of the Goods on the Spanish Shipwreck Gifts and Offerings

The Bajo de la Campana ship also sank with a cargo of valuable items likely intended for Iberia's own native elite clientele: carved ivory artifacts, lumps of amber, alabaster jars, decorated combs, a bronze incense burner, ostrich shells, a limestone pedestal altar, and even what might be either a fan or a flyswatter. The bronze remains of chair legs and a couch frame suggest that the ship was carrying a set of ornate furniture. According to Polzer, all of these objects may have been destined for the household of an important native Iberian. "They see to form a single, complete set of feasting equipment—couchand side table, accompanying incense burners, tableware, wine preparation dishes, and a fan or fly whisk," he says. [Source: Jason Urbanus, Archaeology magazine, May/June 2016]

He believes it is an indication of gift exchange, possibly with a specific individual. Also found aboard was the raw material, in the form of elephant tusks, for the manufacture of luxury items. They were likely headed for carving workshops along the Iberian coast. Elephant ivory would have been common and available to Phoenician merchants through their colonies in North Africa. While a collection of more than 50 tusks was discovered, at least 11of those have proved perplexing to archaeologists. They have been found to bear Phoenician religious inscriptions, which made their inclusion in a cargo of unprocessed ivory odd.

All of the inscriptions are votive in nature, containing a personal name and a declaration of piety to a god or a request for a blessing. One asks the Phoenician goddess Ashtart for protection, another entreats the god Eshmun to deliver the dedicatee from harm. These objects would have been intended to be deposited in a Phoenician shrine or sanctuary and remain there in perpetuity. "They really should not be on board this or any other ship," Polzer says. "I believe that their presence on this ship indicates that temple priests were selling objects on the sly, presumably for personal gain." With everything that was discovered at the Bajo de la Campana wreck site, all of the varied human enterprise and activity represented there, it is perhaps no surprise that evidence of nefarious ancient cargo came to light as well.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Mesopotamia sourcebooks.fordham.edu , National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, especially Merle Severy, National Geographic, May 1991 and Marion Steinmann, Smithsonian, December 1988, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Discover magazine, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, BBC, Encyclopædia Britannica, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Time, Newsweek, Wikipedia, Reuters, Associated Press, The Guardian, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024