ARCHAEOLOGY

Opening King Tut's tomb Archaeology is the study of historic or prehistoric people and their culture through the study of their artifacts, monuments and other items they left behind. The word archaeology is derived from the Greek words “archeo,” meaning “chief” and “ology” meaning “study of”.

Many archaeological sites are discovered accidently, often during construction projects. Some archaeologists call what they do as “running in front of bulldozers to retrieves objects before construction at a site begins.” Other are uncovered by following clues in historical records or digging where mounds and ruined buildings have been found.

On modern archeologists, the German film director Werner Herzog told Archeology magazine, “It's quite extraordinary what they are doing now. How they have new, almost forensic-like science to collect pollen and understand the vegetation. They do things that are unprecedented, in a way, and it's very beautiful to see that. I'm really intrigued by modern-day archaeology. For example, a square foot in one of the caves in the film — it took five months to remove half a centimeter of sediment. Every single grain of sand was picked up with a pair of pincers and documented with laser measurements. And all of a sudden it makes clear things like the flute, the flute from Hohle Fels Cave [in Germany], which is mammoth ivory, and the tiny fragments that were not understood for decades, but they were preserved. That's a fine thing, yes, until somebody came who had the kind of imagination like the young woman who is in the film, Maria Malina, an archaeological technician who had the insight and started to put the fragments together.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ARCHAEOLOGY DATING METHODS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LOOTING OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES factsanddetails.com ;

HOMININ PALEONTOLOGY (4 MILLION TO 10,0000 YEARS AGO) factsanddetails.com ;

EARLY MAN AND HOMININ DATING TECHNIQUES factsanddetails.com ;

GENETICS, DNA STUDIES AND HOMININS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Archaeology” by Robert Kelly and David Thomas (2016) Amazon.com;

“Written in Bones: How Human Remains Unlock the Secrets of the Dead”

by Paul Bahn PhD (2012) Amazon.com;

“Evolution's Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins” by Peter Ungar (2017) Amazon.com;

“An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Archaeology: The Key Sites, Those who Discovered Them, and How to Become an Archaeologist by Christopher Catling and Paul Bahn (2022) Amazon.com;

“Archaeology: The Essential Guide to Our Human Past”

by Paul Bahn and Brian Fagan (2017) Amazon.com;

“Archaeology Essentials: Theories, Methods, and Practice” by Colin Renfrew , Paul Bahn, et al. (2024) Amazon.com;

“Field Methods in Archaeology” by Thomas R. Hester (2009) Amazon.com;

“Scientific Dating in Archaeology” by Seren Griffiths (2022) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeologist's Laboratory: The Analysis of Archaeological Evidence” by Edward B. Banning (2020) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Kathryn A. Bard) Amazon.com;

“Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt” by Steven Blake Shubert and Kathryn A. Bard (2005) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes” By Svante Pääbo (2014) Amazon.com;

“Unlocking the Past: How Archaeologists Are Rewriting Human History with Ancient DNA” by Martin Jones (2016) Amazon.com;

“Origin: A Genetic History of the Americas” By Jennifer Raff, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas (Twelve, 2022); Amazon.com;

“he Archaeology of Childhood: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on an Archaeological Enigma” by Güner Coşkunsu (2016) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Disease” by Charlotte Roberts, Keith Manchester Amazon.com;

History of Archaeology

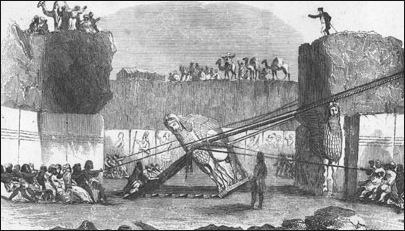

Early work in Mesopotamia Looting ancient sites and digging up graves to find treasures has been around since the beginning of civilization but painstakingly excavated sites and carefully studying what is there — archaeology, in other words — is a relatively new idea.

The modern science of archaeology was invented in the 17th century. Early pioneers included Jacob Spon (1647-1685), a century physician who traveled throughout Greece and Asia Minor, comparing sites with historical texts, and J.J. Winckelmann, who wrote “ History of Art of Antiquity” in 1764. Many objects obtained in the Middle East were obtained through the Ottoman patronage system. See Iraq.

Andre Lero-Gourhan revolutionized the practice of excavations by recognizing that vertical digs destroy the context of a site. Over 20 years (1964-1984) he and his students painstakingly excavated “scraping away the soil in small horizontal squares and making notes of where everything was located” the 12,000-year-old site of Pincevent, offering of the most detailed picture up to that point of life in the Paleolithic period.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Archeological Park of Pompeii told the The New Yorker: Archeology “is a field that is very much evolving, thanks to new discoveries and methodologies, but also thanks to new questions...Today, we have a much broader view of ancient society. Archeology started as a field dominated by male, upper-class, European, white scholars, and noblemen and connoisseurs, and this very much conditioned archeological research, and what people were interested in. Now, thanks to new perspectives — post-colonial studies, and gender studies, and feminism — we have a really different perspective on antiquity.” [Source: Rebecca Mead, The New Yorker, November 22, 2021]

See Pompeii, Troy, Mycenae.

Drawing Clues from Archaeology

Archaeologists attempting to piece together the past from poetry shards and piles of stones. They dig into the earth — a process known as excavating’searching for artifacts (objects) from an ancient people and try to date and figure the significance of these artifacts. Context is critical to understanding the significance of artifacts. This determined by the position of excavated objects compared to other objects and the remains of buildings and other structures. Archaeologists seek out trash dumps, which often contain vital clues to unmasking everyday life. The fact that archaeologists are much more skilled at gleaning large amounts of information from ancients scraps that previously would have been discarded has meant that process of excavating take much longer. Ancient people rarely threw out what was valuable to them. Things like jewelry and crafts are often found in graves but they have often already been taken by graverobbers and looters.

Most of things that we know about everyday life in ancient times has been determined by looking at scenes depicted on vases, examining tools, remains and artifacts left at archaeological sites and drawing clues from literary and historical texts. The age of an individual died can be determined by looking at the knitting of the suture on the cranium, which closes as people age, and by noting how worn the teeth are. Children can be aged by which teeth have emerged from the jaw. Pitted tooth enamel is an indicator or starvation and malnutrition. The easiest way to determine sex is by examining the pelvic bones. Females have large round openings, large enough to accommodate the head of a baby. Males have a heart-shaped opening.

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: The Daily Beast spoke to archaeologist and ancient historian Dr. Mark Letteney, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT, about how archaeologists approach strange artifacts and what we might make of this burial. The first thing you do when you uncover something, said Letteney, “is stop. Archaeology is a destructive endeavor — the real data of archaeology is not the artifacts, but the specific properties of their deposition: how they appear in the ground, in what shape, orientation, and in what relation to the other material in the ground?” It’s not just about the objects, it’s about “how they got to be where they are when we come across them. ” Letteney said that you could unearth the Holy Grail, but it would be archaeologically meaningless unless you recorded exactly where you found it in relation to everything around it. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 29, 2023]

Recording the data associated with a new discovery can take many forms: older archaeologists relied upon a brief sketch and notes, but today people are more likely to use photographs. The locational data of points of interest are logged, soil samples might be taken for laboratory testing, and 3D models of the first evidence might be built. Multiple iterative stages of logging of evidence are undertaken. The goal of all of this, said Letteney, “is that another archaeologist could read through your notes, look at the data that you collected, and correct your inevitable mistakes. ”

Nature of Archaeological Evidence

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “What kinds of questions does archaeological evidence answer? It tells us certain things definitively: where people lived; what kinds of houses they lived in; how many of their houses were clustered together (in other words, the size of their villages) and how close or far apart from one another they lived; what they ate (based upon the analysis of animal and fish bones in their garbage heaps); how they disposed of dead people; and what kinds of implements they used, especially pottery, stone objects, and weapons. There are some other kinds of questions about which archaeology gives us clues but no definitive answers. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“The laws of physics determine what sort of objects survive in the ground through centuries of time. Dry climates and sandy soils preserve delicate materials better than wet climates and muddy soils; this is why the vast majority of preserved papyrus fragments from classical antiquity come from the dry sands of Egypt. The possibility of preservation also depends on the material. Wooden objects and wooden structures in most circumstances do not survive very long (although wood does survive better in wet conditions than dry, and the wooden hulls of ships are sometimes preserved for thousands of years under the sea floor). ^*^

“Many buildings in antiquity had stone foundations (which do survive) and wooden superstructures (which do not). Neither do paints last; the temples and other public buildings which we are used to thinking of as being the color of marble were in fact brightly painted, as were marble statues. Metal objects have a better chance of surviving; a relatively small number of bronze and iron objects have survived from antiquity, often in a state of advanced corrosion. In particular circumstances (such as if the ground is frozen, or the item is sealed in an airtight container) cloth or leather items may survive.” 8^*

Drawing Inferences from Archaeological Data

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: Deciding exactly what you have found is especially challenging. The process involves experience, expertise, and scholarly curation. Identifications “are made on the basis of comparison” you take your new discovery and compare it “with similar sites, artifacts, or depositions that have been securely identified. ” People who have a lot of experience excavating and analyzing artifacts from a particular region and period can notice the similarities between new discoveries and those that have already been documented. [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, January 29, 2023]

Once you know the “when” of the context, you can then turn to the significance of the deposit (the thing you discovered in the ground). What does it represent? What does it mean? How was it used? Or even just, what is it? Dr. Mark Letteney, a postdoctoral fellow at MIT said that this is where the hard work really starts. It’s basically an exercise in comparison: you compare your archaeological context to other contexts from similar places and similar periods. This takes an enormous amount of time. Letteney said that this is one of the reasons that tHere’s such a delay in archaeological publishing. You might see a press announcement about an amazing discovery, but the formal site report will not come out for years or possibly even decades. This is because archaeologists are spending hundreds of hours gathering data, and comparing their discoveries to other forms of evidence.

There are some instances where there is no data with which to make sense of a discovery. When that happens, Letteney told me, archaeologists turn to other ways of making sense of things — primarily, anthropological data and theories of human interaction and motivations. THere’s a joke among archaeologists, he told me, that when they are truly at a loss, they label something “ritual” and call it a day. Ikram’s study (and by extension Belova and Savinetsky’s) is on much firmer ground as religion is a plausible explanation for any kind of burial practice. In this case, the identification seems particularly secure. After all, no parent of a dog-walking-averse pre-teen would believe that a child looked after 142 dogs without a very good reason.

Archaeology Techniques

Archaeologists crawl, kneel and laboriously brush away dirt with a brush from objects they unearth. Soil, sand and excavated material are sifted through screen to retrieve small artifacts. Archaeologists often dig a series of trial trenches to figure out the best places to excavate. Photographs are taken of each phase of the work for future reference. Soil is sifted so that small objects are not overlooked. When something is found it is often swept with a brush and removed with a trowel so it doesn’t break.

Artifacts are brought into workshops are catalogued. Delicate objects are restored in situ. Other objects are restored in the work room or laboratory. Bronzes and other objects are often restored with distilled water, which does not remove the patina (the thin coating that forms on stone, ceramic or metal over centuries). The patina us often checked to determine whether an object is real or fake. Pots are restored by removing old varnished made from glues made from animal hooves and applying sealants that do not become discolored.

Construction projects often lead to new archaeological discoveries. For example, in the early 2010s, during expansions of Highway 1, the main road connecting Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, excavators discovered 9,500-year-old animal figurines, a carving of a phallus from the Stone Age and a ritual building from the First Temple era. [Source: Live Science, November 25, 2013]

Chemical analysis and imaging techniques are sometimes employed. In the early 2020s, X-rays of a sword that had been sitting in museum storage revealed that was from the Bronze Age. According to Live Science, while preparing for an exhibition, Hungarian archaeologists asked museum curators to show them the sword for themselves. With the help of field scientists, including a chemist, the archaeologists used X-rays to scan the weapon and compared its "chemical makeup to other known Bronze Age swords in Europe." The researchers discovered that the swords’ "content of bronze, copper and tin were nearly identical," according to the statement. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, January 25, 2023]

Book: “ Written in Bones: How Human remains Unlock the Secrets of the Dead” by Paul Bahn

Archaeology Layers and Positions

It is very important to record the position of all the objects that are found. The vertical position of an object, as defined by the layer in the earth, or strata, where it is found reveals its date or at least it relations to what came before and after it. Archaeologists carefully remove earth layer by layer when they are excavating so they can determine the date or period of objects and not mix them up with objects from other periods.

The strata are often look like the layers of a layer cake, with the oldest layers being the ones that are the deepest in the earth. Each layer and the locations of artifacts are carefully measured, often with surveying equipment. The layers can be dated by using the dating methods listed below.

Many ancient buildings were constructed of mud brick or stone. Over time, walls of these structures tended to weaken and collapse, often due to rain or an attack, and the ruins were leveled off before a new structure was raised. Each time a building collapsed and a new one was built on top of it and a new layer of strata was created. Over centuries many layers are piled on top of one another and a mound is created.

The horizontal position of an object and it locations in relation to other objects often give clues to what the object is used for. The locations of each significant object found are recorded using a grid system that usually can be overlaid on the excavation site. These days measurements can be done with lasers and excavation records and survey data can quickly be transferred to computer to create a three-dimensional model of excavated objects and their positions.

Stratification and Commerce

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “The distribution of pottery types into particular layers of an excavation is not always perfect. Sometimes a single layer contains pottery from two different periods. Come back for a second to the hypothetical example of the Bell-bottom people versus the Saggers. Suppose you found a few pairs of bell-bottoms among the baggy shorts. Since they are relatively rare compared to the shorts, we can posit that a few people in the 1990's liked to wear clothes from the 1960's. The bell-bottoms might actually date back to the 1960's; the analogous pottery item in this case would be called an heirloom. Or, the bell-bottoms might have been made in the 1990's in a deliberate effort to achieve that 1960's look; the pot in this case would be called archaizing. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“What if, on a level which had primarily bell-bottoms, some baggy shorts showed up? Or, in pottery terms, what if you find traces of a late style in a layer which the majority of the evidence suggests is early? This situation is much more rare than the previous one. There would be only two possible explanations. One, that the stratification of the site, the levels, had been disturbed at some time between the inhabitation of the area and the excavation. This happens when someone has dug through the levels and jumbled up their contents. If it is established that the levels were undisturbed, that means that the previously existing ruling chronological scheme, which maintained that no one was wearing baggy shorts in the 1960's, was wrong and has to be revised. Archaeologists tend to have a hostile reaction when someone claims that a particular pottery chronology needs revision.^*^

“In addition to knowing the date of manufacture of a particular piece of pottery, it is often also possible to tell where it was made. This in turn allows us to deduce with what other peoples a particular people might have had contact, especially commerce. Goods commonly traded in antiquity, such as wine and oil, were routinely transported in large earthen vessels, called storage amphoras. Sometimes, too, the vessel itself is the import product; this is true in the case of some elaborately decorated pottery (called fine ware, as opposed to coarse ware such as storage amphoras).” ^*^

Stone Tool Terminology

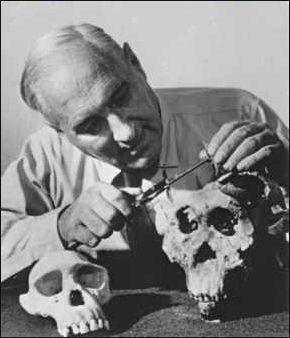

Louis Leakey Stone tools are the oldest surviving type of tool made by hominins, our early human ancestors. It is likely that bone and wooden tools were used quite early, but organic materials deteriorates with time and doesn’t survive like stone. Archaeologists sometimes use the term 'lithics' to refer to all artifacts made of stone. [Source: K. Kris Hirst, Thoughtco.com, March 8, 2017 ==]

Artifacts (also spelled artefacts) are objects or remainders of objects, which were created, adapted, or used by humans. The word artifact can refer to almost anything found at an archaeological site, including andscape patterns, trace elements attached to potsherds. All stone tools and pieces of stone tools are artifacts. ==

Geofacts are pieces of stone that looks as if they can be used as tools, with seemingly human-made edges, that have been created naturally by erosion or being broken and have not been shaped, modified or purposely broken by humans or hominins. Objects that are products of human behaviors are artifacts. Geofacts are produced by natural forces. Telling the different between artifacts and geofacts can often be difficult. ==

An assemblage or haul refers to the entire collection of artifacts recovered from a single site. Material culture is used in archaeology and other anthropology-related fields to refer to all the corporeal, tangible objects that are created, used, kept and left behind by past and present cultures. ==

Working on an Archaeological Dig

Describing his experience, working as a volunteer at an Early Bronze Age site in Mitrou, a small island in southern Greece, Stefan Beck wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “It was before six on my first morning...I found myself hauling potsherds, pickaxes, shovels and computers from a gecko-infested “apotheke” (warehouse) to a big orange truck parked outside. When the truck was full, we headed off, a police escort alongside to protect us from hijackers — that is to say, from antiquities smugglers eager for our loot. We then unloaded it at a new, more spacious apotheke.”

“The second day was spent removing backfill at the site. At the end of each season of exploration, the archaeologists put a tarp over the site and then covered it with soil to protect artifacts from the ravages of weather...here I began to grasp how little of archaeology is strictly “digging.” As the dirt came out these scientists paid careful attention to the profile of the tarp beneath it; even a after a year, the trench supervisor knew what lay under every contour — a cist tomb, a fragment of wall...The site operated as methodically as an ant arm and with every bit as much purpose.”

“As the days wore on — and my back wore out — I became more impressed by the range of knowledge that mere “digging” required. Archaeology cuts across the shallow trench that divided the hard sciences from the humanities. To get the full value...requires some knowledge of technology, history, language (both ancient and modern), classical literature, zoology , botany, geology and art...And how can I forget the charming field of mortuary analysis.”

Pottery Analysis

Almost every archaeological site yields thousands of pieces of broken pottery known as pottery shards, or potsherds. Because pottery was cheap and easy to make, ancient people thought nothing of throwing it away. Archaeologists are adept at deciphering pottery shards. They can often date a site, gauge its level of sophistication and establish trading patterns solely by examining pottery shards.

There are tables and guides that archaeologists can refer to identify potsherds. Different kinds of pottery can be differentiated by the designs, pottery making process and the composition of clay, glazes and pigments used to make it. Large data bases of over 7,000 kinds of pottery from different ages and different sites around the Mediterranean alone can be used to identify the date and origin of the objects. The analysis is based on the type of clay used, pottery type and ornamentation.

Pottery can be dated measuring the effects of radiation via thermolumiscence, by carbon dating food remains or dating the sediments of the layers in which the pottery was found. A “clay atlas” has been created for “fingerprinting” pottery for 35 trace elements. This atlas is especially useful with small pottery shards.

Importance of Pottery

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “One material which totally defies the corrosive effects of long periods of burial is baked clay. At almost every single place where humans have lived, from the Neolithic age on, remains of their pottery can be discovered. Pottery is enormously important to archaeologist, no only because of its omnipresence, but also because it permits them to answer another question with near certain exactitude: when did these people live? Pottery answers this question because people of different time periods and different cultures made different kinds of cups, pots, jars and so forth. Pottery varies according to the shape of the vessel, the type of clay, the nature of the decoration outside or inside the pot, and the technique employed for shaping and firing. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“Imagine that an archaeologist from far in the future was digging a late 20th century site, and that clothing served for him the function that pottery does for archaeologists of ancient sites. He finds two layers, each representing the occupancy of a space by a different group of people at a different time. In settlement "A" everyone wore bell-bottom jeans; in settlement "B" (which is closer to the surface than settlement "A") everyone wore big baggy shorts which reached to mid-calf. The archaeologist would then refer to an already established chronology based upon the preference for pants styles at other late 20th century American sites, and he would then be able to date settlements "A" and "B" within a margin of error of around five to ten years. And in fact a margin of error of ten to fifteen years is typical for dates based solely or primarily upon pottery evidence.^*^

“Pottery dating is not perfect. First of all, one might think when finding out for the first time about how important pottery is for archaeological dating, it is so low-tech. What about the analysis of the breakdown of radioactive isotopes, carbon 14 dating? Actually, carbon 14 dating tends not to be very helpful to archaeologists (more so to geologists and the like). Carbon-14 dating only works on items which contain carbon, such as wood or coal. And in some cases C-14 dating can tell you only when an object's raw material first came into existence, as opposed to what you really want to know, which is when the material was shaped into its current form.” ^*^

Written Sources and the Limitations of Archaeology

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “What kinds of question can archaeology not answer? Perhaps this would be better phrased as, what kinds of questions can archaeology not answer as well as written sources? Archaeological evidence is less useful than written sources for figuring out what a group of people thought, what they believed, as well as for informing us about their political structures, about how societies organized themselves. Even so there are some peoples and some periods from antiquity, for which there are either no textual sources or only textual sources filled with guesses and false information. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“This is essentially true for all of the non-Greek inhabitants of Italy down to the establishment of the Roman Republic in 510 B.C. In such cases archaeological evidence is pressed into service. For example, figurines presumed to represent deities spark inferences about the religious beliefs and practices of a people. Female figures with oversized breasts and hips, or large pregnant looking bellies, become fertility goddesses. This is useful up to a point but it can go too far, as when far-reaching theories about matriarchal societies are spun on the basis of statues of this sort. Likewise, if a settlement has one very large house or palace and a number of other smaller dwellings clustered around it, it becomes tempting to posit that the large house housed not only a king and queen, but also served as a center for worship and for the decision of judicial questions.

“So there is a delicate balancing act involved with interpreting archaeological evidence, just as there is with written texts; the methods, however, are dissimilar. In the first case the rule is, not to try to go beyond the conclusions which the evidence will reasonably allow. In the second case, the rule is to distinguish fact from fiction (fiction not being consciously presented as such by ancient historians) and to show how or why distortion has come in to the historical record. In the best case scenario, you are dealing with a period for which there is both archaeological and historical evidence, and the former acts a check on the latter. ^*^

“The Romans believed that King Servius Tullius ruled the city of the seven hills during the years 578-535, and that one of his greatest achievements was the construction of a massive fortification wall. But the archaeological record belies that claim. It proves that the wall which the Romans believed to be the work of Servius Tullius, which they called the Servian Wall, was in fact no older than the sack of the city by the Gauls in 390. This is only one of many such cases involving buildings and monuments falsely attributed to the kings. Does this mean, then, that we cease to believe in all of the other acts, many of them not verifiable by the use of archaeological evidence, which were attributed to Servius Tullius?” ^*^

Genetics and Linguistics

Genetic studies of ancestry are based on observations of mitochondrial DNA. Unlike chromosomal DNA, which changes when sperm and an egg fuse, mitochondrial DNA is passed on only by the mother, unchanged and unaltered, except for occasional mutations, which occur every several thousand years or so and provide distinctive markers from which common ancestry can be traced. The more differences there are between samples, the longer ago they diverged. In this way mitochondrial DNA not only indicates how similar or dissimilar two people are but also indicates how far one must go back to find a common ancestor.

Geneticists studying the DNA of different groups focus on the Y chromosome, which is passed on along the male line with no input from mothers and thus offers clues of the ancestry of the group being studied. To study the DNA of an individual, DNA is taken from blood (if available) or available tissues, hair or even bone. Enzymes are added to isolate specific regions of the Y-chromosome DNA that are to be analyzed and studied.

Human-Neandertal mtDNA

Geneticists have a strong interest in microsatellites, short section of junk DNA that mutate more rapidly than long section and do so at a constant rate, providing a kind of clock allowing scientists date the age of certain chromosomes and use that information to figure when certain populations emerged.

Most western Europeans carry a Y-chromosome-type marker called M173. Studies of microsatellites indicate that the individual who originated M173 lived 30,000 years ago. Most Middle Eastern men carry the M89 Y-chromosome marker, which is dated to 45,000 years ago, and M172 marker, which dates back to 12,000 years ago.

By studying commonalities between languages, linguists can go back in time and figure out which people are related to each other and when. Sometimes they identify key words and work look for similarities and work their way backwards in a way that is not unlike that of geneticists.

These days physical scientists often outnumber archaeologists at archaeological sites. There are botanist, zoologists, chemists, and scientists

Book: “ Lost Languages; the Enigma of the World’s Undeciphered Scripts “ by Andrew Robinson

RELATED ARTICLES: GENETICS, DNA STUDIES AND HOMININS factsanddetails.com

Modern Archaeological Techniques

Sites are located with ariel surveys and satellite imagery. Satellite images sometimes reveals the outlines of temples, towns and trade routes obscured by sands or vegetation cover or sites that are otherwise missed on the ground. Multi-spectral light-imaging technology, designed for NASA for the study on planet surfaces, has made it possible to read papyrus scrolls badly burned in the eruption of Pompeii. Using extremely sensitive filters, scientists are able to see black ink written on the burnt black papyrus.

Sometimes small camera are inserted into tombs. First a hole is drilled and a tube is inserted and the camera is inserted through the tube. An effort is made to make sure the interface is airtight so that no air or contaminants enter the burial chamber.

Magnometers and metal detectors are used to search for metal objects under the surface. Archaeologists can also send electric currents through the ground at depths of a few foots. By observing differences in the resistance to current they can record differences in subsurface densities and determines what is below: foundations, pavement or just dirt. This helps locate buildings and determines the lay out of settlements.

Ultrasound and seismic generating machines are now being used by Egyptologists to locate temples and ruins covered by sand. Scientists are also using theodolites, electric distance measurers and the technique of photogrammetry. They shoot seismic waves through the sand and the through the monuments. Magnetometers are used to detect tombs. The underground radar does not work well when water is present.

CT scan for the Iceman Mummies are being scanned with CT (computerized tomography) technology to determine their age, sex and cause of death and whatever else can be gleaned from them. With this technique the mummy is X-rayed at different angles to produce a 3-D composite image of the entire body. One advantages of such scans is the mummy does not have to be unwrapped. The details are better than those of X-rays. Using this technique archaeologists and specialists check for evidence of trauma, vitamin deficiencies, degenerative diseases.

Underwater archaeologists use sonar and multibeam bathymetric technology to scan the sea floor and send down remote control camera. Doing excavations of shipwrecks and ruins below about 50 meters is very difficult and expensive because those depths are beyond the reach of divers who can work any great length of time. See Bronze Age Ship, Romans, Greeks

Pollen, Food and Protein Analysis

Foods and drinks from ancient times can be determined by analyzing samples in a spectrometer and looking for organic compounds, especially long-chain lipids, triglycerides and fatty acids that characterize many foods. The presence of beer can be determined by the presence of calcium oxalate (“beerstone”). Wine can be determined by tartaric acid and its salts. Samples can be extracted from pottery and jars with solvents. Specific fatty acids can be markers for meat such goat, mutton and pork. Anisic acid is an indicator of anise, or fennel.

Protein analysis of archaeological ceramics has yielded important and interesting results. Molecular techniques applied to ancient pottery can reveal broad classes of food — such as evidence of dairy or animal fat — but an analysis of proteins allows a much more detailed information. Protein analyses can identify foodstuffs in situ down to the species level, in samples as old as 8000 years. If residues on the insides of ceramics were are well-preserved they can contain a wealth of information. The removal of these residues can be a common practice among archaeologists as part of the preservation and cleaning process. "These results highlight how valuable these deposits can be, and we encourage colleagues to retain them during post-excavation processing and cleaning," Eva Rosenstock of the Freie Universität Berlin said.

Pollen grains of specific species have vary distinctive shapes and surface patterns. They can be easily identified under a microscope and scientists can use them to date objects and describe the habitats of objects that contain them. By identifying ancient seeds and pollen archaeologists can figure what people ate and drink and get some insight into weather patterns in ancient times. Archaeologists can also figure out trade patterns by analyzing the chemicals in paint and vegetable dyes found in scraps of clothes.

Dating Methods

Historical records only go back to around 2000 B.C. Dating of ancient Egypt, and Sumer was done by examining written records of the durations of reins of kings. By working backwards archaeologists came up with the date of 3000 B.C. when those civilizations first evolved.^^

Ancient icons are indispensable archaeological tools. Minted to record a major historical event or the deification of an emperor of major figure, they can help scholar date objects and layers with some precision and provide important information on trade and political ties. Coins are used in a similar fashion. The oldest coins with dates to around 700 B.C.

Sometimes geologists can help date objects by measuring the amount of rain wear in cracks, alluvial deposits by streams and glaciers and layers of silt in lakes. Lichenometry is useful in measuring lichens from 100 and 9,000 years old.

Alexander Marshak identified the Ishango Bone. Afterwards he investigated scratched pebbles and other materials from the last Ice Age in EUROPE and discovered inconclusive evidence of time-keeping [time factoring] as far back as about 45000 years.

See Separate Article: ARCHAEOLOGY DATING METHODS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024