IRON AGE

Iron Age jewelry

The Iron Age began around 1,500 B.C. It followed the Stone Age, Copper Age and Bronze Age. North of the Alps it was from 800 to 50 B.C. Iron was used in 2000 B.C. It may have come meteorites. Iron was made around 1500 B.C. Iron smelting was first developed by the Hittites and, possibly Africans in Termit, Niger, around 1500 B.C. Improved iron working from the Hittites became wide spread by 1200 B.C. See Hittites Below

Because it keeps an edge better than bronze and can more easily be shaped of furnaces are hot enough, iron proved to be an ideal material for improving weapons and armor as well as plows (land with soil previously to hard to cultivate was able to be farmed for the first time). Bronze is stronger and harder than iron because it is an alloy of two other metals, making it denser and difficult to break with less friction. On the other hand, iron is a natural ore and less dense, and can be bent easily. Bronze can be melted easily, whereas iron needs a special furnace.

Although it is found all over the world, iron was developed after bronze because virtually the only source of pure iron is meteorites and iron ore is much more difficult to smelt (extract the metal from rock) than copper or tin. Some scholars speculate the first iron smelts were built on hills where funnels were used to trap and intensify wind, blowing the fire so it was hot enough to melt the iron. Later bellows were introduced and modern iron making was made possible when the Chinese and later Europeans discovered how to make hotter-burning coke from coal. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

According to People World: “In its simple form iron is less hard than bronze, and therefore of less use as a weapon, but it seems to have had an immediate appeal - perhaps as the latest achievement of technology (with the mysterious quality of being changeable, through heating and hammering), or from a certain intrinsic magic (it is the metal in meteorites, which fall from the sky). [Source: historyworld.net]

The technology of iron is believed to have made its way to China via Scythian nomads in Central Asia around 8th century B.C. In May 2003, archeologists announced they found remains of an iron casting workshop along the Yangtze River, dating back to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 - 256 B.C.) and the Qin Dynasty (221 -207 B.C.). See Below

See Separate Article: EARLIEST IRON AND STEEL: METEORITES, HITTTIES, AFRICA, SPAIN AND SRI LANKA factsanddetails.com

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Livescience livescience.com/

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Iron Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024)

Amazon.com;

“The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age” by Colin Haselgrove , Katharina Rebay-Salisbury, et al. (2023) Amazon.com;

“Assyria to Iberia: At the Dawn of the Classical Age” by Joan Aruz, Yelena Rakic, Sarah Graff Amazon.com;

“The Bronze Age: A History from Beginning to End” by Hourly History (2024) Amazon.com;

“Bronze Age Lives” by Anthony Harding (2021) Amazon.com;

“The Aegean from Bronze Age to Iron Age: Continuity and Change Between the Twelfth and Eighth Centuries BC” by Oliver Thomas Pilkington Kirwan Dickinson (2006) Amazon.com;

“After 1177 B.C.: The Survival of Civilizations” by Eric H. Cline (2024) Amazon.com;

“Iron-Age Societies: From Tribe to State in Northern Europe, 500 BC to Ad 700" by Lotte Hedeager and John Hines (1992) Amazon.com;

“The Atlantic Iron Age” by Jon Henderson (2007) Amazon.com;

Copper Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age

Archaeologists usually shy away from assigning fixed dates to the Neolithic, Copper, Bronze and Iron Ages because these ages are based on stages of developments in regard to stone, copper, bronze and iron tools and the technology used to make and the development of these tools and technologies developed at different times in different places. The terms the Stone Age, Bronze Age and Iron Age were coined by the Danish historian Christian Jurgen Thomsen in his Guide to Scandinavian Antiquities (1836) as a way of categorizing prehistoric objects. The Copper Age was added latter. In case you forgot, the Stone Age and Copper Age preceded the Bronze Age and the Iron Age came after it. Gold was first fashioned into ornaments about the same time bronze was.

David Silverman of Reed College wrote: “It is important to understand that terms such as Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age translate into hard dates only with reference to a particular region or peoples. In other words, it makes sense to say that the Greek Bronze Age begins before the Italian Bronze Age. Classifying people according to the stage which they have reached in working with and making tools from hard substances such as stone or metal turns out to be a convenient rubric for antiquity. Of course it is not always the case that every Iron Age people is more than advanced in respects other than metalworking (such as letters or governmental structures) than the Bronze Age folk who preceded them. [Source: David Silverman, Reed College, Classics 373 ~ History 393 Class ^*^]

“If you read in the literature on Italian prehistory, you find that there is a profusion of terms to designate chronological phases: Middle Bronze Age, Late Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age I, Middle Bronze Age II, and so forth. It can be bewildering, and it is damnably difficult to pin these phases to absolute dates. The reason is not hard to discover: when you are dealing with prehistory, all dates are relative rather than absolute. Pottery does not come out of the ground stamped 1400 B.C. The chart on the screen, synthesized from various sources, represents a consensus of sorts and can serve us as a working model.

Iron and the Hitittes

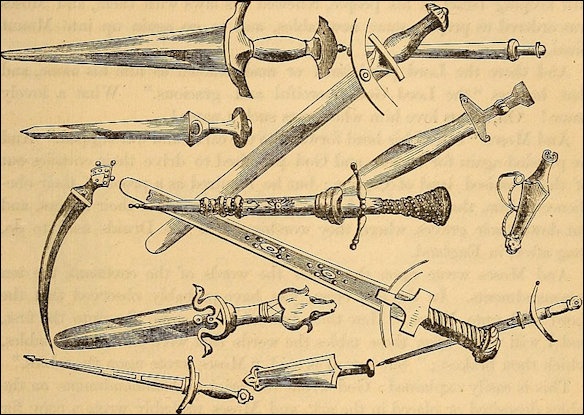

7th century BC iron swords from Italy

The Hittites are regarded as the first people to produce iron and thus are the civilization that ushered in the Iron Age. About 1200 B.C., scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs. Lethal Celtic iron swords dating back to 950 BC have been found in Austria and its is believed the Greeks learned to make iron weapons from them.

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows.

The Hittites mined iron in the Black Sea region. Hittite Iron mines supplied the region with metal. Metal making secrets were carefully guarded by the Hittites and the civilizations in Turkey, Iran and Mesopotamia. Iron could not be shaped by cold hammering (like bronze), it had to be constantly reheated and hammered. The best iron has traces of nickel mixed in with it.

See Separate Article: HITTITES AND IRON africame.factsanddetails.com

Iron-Making First Achieved in Africa?

The generally accepted view is that Iron smelting was first developed by the Hittites, an ancient people that lived in what is now Turkey, around 1500 B.C.. Some scholars argue that iron-making was developed around the same time by Africans in Termit, Niger around 1500 B.C. and perhaps even earlier at other places in Africa, notably Central African Republic.

A 2002 UNESCO published study suggested that iron smelting at Termit, in eastern Niger may have begun as early as 1500 B.C.. This finding, which would be of great importance to both the history of Niger and the history of the diffusion of Iron Age metalworking technology in all of sub-Saharan Africa, is as yet contentious. Older accepted studies place the spread of both copper and Iron technology to date from the early first Millennium CE: 1500 years later than the Termit Massif finds

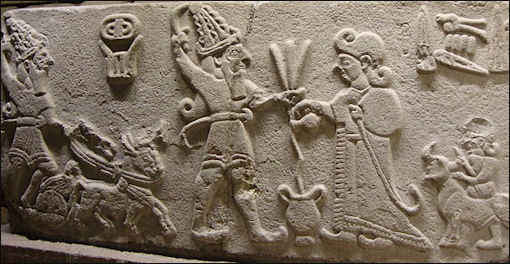

9th century BC depiction of men with swords from the Hittite city of Sam'al

According to the 2002 UNESCO report: “Africa developed its own iron industry some 5,000 years ago, according to a formidable new scientific work from UNESCO Publishing that challenges a lot of conventional thinking on the subject.iIron technology did not come to Africa from western Asia via Carthage or Merowe as was long thought, concludes "Aux origines de la métallurgie du fer en Afrique, Une ancienneté méconnue: Afrique de l'Ouest et Afrique centrale". The theory that it was imported from somewhere else, which - the book points out - nicely fitted colonial prejudices, does not stand up in the face of new scientific discoveries, including the probable existence of one or more centres of iron-working in west and central Africa andthe Great Lakes area. [Source: Jasmina Sopova, Bureau of Public Information, The Iron Roads Project. Launched by UNESCO in 1991 as part of the World Decade for Cultural Development (1988-97)]

Heather Pringle wrote in Science ““Some of the most important sites in Africa supporting very early evidence for the invention of iron in Africa include Termit in East Niger, yielding dates as early as 1500 B.C.; The Air Mountains also in Niger yield very early dates for copper metallurgy as early as 3000--2500 B.C.. And in Nigeria there is also the Nok Culture yielding dates as early as 900 B.C. ( and according to Cheik Anta Diop and others, even later) for iron. In the great Lakes region associated with Urewe Ceramic culture the dates are estimated to be as early as 1450–500 B.C. for iron technology. [Source: Heather Pringle, "Seeking Africa's First Iron Men", Science January 9, 2009: Vol. 323 no. 5911 pp. 200-202]

Iron Age Palestine (1200 - 550 B.C.)

Abercrombie wrote: “The Iron Age is divided into two subsections, the early Iron Age and The Late Iron Age. the early Iron Age (1200-1000) illustrates both continuity and discontinuity with the previous Late Bronze Age. There is no definitive cultural break between the thirteenth and twelfth century throughout the entire region, although certain new features in the hill country, Transjordan and coastal region may suggest the appearance of the Aramaean and Sea People groups. There is evidence, however, that shows strong continuity with Bronze Age culture, although as one moves later into the early Iron Age the culture begins to diverge more significantly from that of the late second millennium. [Sources: John R. Abercrombie, University of Pennsylvania, James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts (ANET), Princeton, Boston University, bu.edu/anep/MB.html |*|]

“The Late Iron Age (1000-550) witnessed the rise of the states of Judah and Israel in the tenth-ninth century. These small principalities exercise considerable control over their particular regions due in part to the decline of the great powers, Assyria and Egypt, from about 1200 to 900. Beginning in the eighth century and certainly in the seventh century, Assyria reestablishes its authority over the eastern Mediterranean area and exercises almost complete control. The northern state of Israel is obliterated in 722/721 by King Sargon and its inhabitants taken into exile. Judah, left alone, gradually accommodates to Assyrian control, but towards the end of the seventh century it does revolt as the Assyrian empire disintegrated. Judah's freedom was short-lived, however, and eventually snuffed out by the Chaldean kings who conquered Jerusalem and took some of the ruling class into exile to Babylon. During the period of exile in Babylon, the area, particularly from Jerusalem south, shows a mark decline. Other areas just north of Jerusalem are almost unaffected by the catastrophe that befell Judah. |*|

Hittite bas relief

“The University of Pennsylvania Museum possesses a rich collection in Iron Age material from almost all its excavated sites. The Beth Shan strata are particularly helpful in illustrating the continuity with the Bronze Age in Iron I. The same probably can be said for the Sa'idiyeh cemetery. Beth Shemesh, however, shows the discontinuity with the Late Bronze Age given its somewhat intrusive Aegean evidence usually associated with the Philistines. In The Late Iron Age, the following sites adequately cover the culture: Gibeon, Beth Shemesh, Tell es-Sa'idiyeh, Sarepta and to a lesser extent Beth Shan. Many of the small finds photographed below come from Gibeon, Sa'idiyeh and Beth Shemesh. Models and simulations are taken from publications of Sa'idiyeh and Sarepta. |*|

Iron Tools in Ancient Egypt

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows. About 1200 B.C., scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs.

André Dollinger wrote in his Pharaonic Egypt site: “Rare meteoritic iron has been found in tombs since the Old Kingdom, but Egypt was late to accept iron on a large scale. It did not exploit any ores of its own and the metal was imported, in which activity the Greeks were heavily involved. Naukratis, an Ionian town in the Delta, became a centre of iron working in the 7th century B.C., as did Dennefeh. [Source: André Dollinger, Pharaonic Egypt site, reshafim.org.]

“Iron could not be completely melted in antiquity, as the necessary temperature of more than 1500°C could not be achieved. The porous mass of brittle iron, which was the result of the smelting in the charcoal furnaces, had to be worked by hammering in order to remove the impurities. Carburizing and quenching turned the soft wrought iron into steel.

“Iron implements are generally less well preserved than those made of copper or bronze. But the range of preserved iron tools covers most human activities. The metal parts of the tools were fastened to wooden handles either by fitting them with a tang or a hollow socket. While iron replaced bronze tools completely, bronze continued to be used for statues, cases, boxes, vases and other vessels.”

Iron Working in Ancient Egypt Developed from Meteorites

Ancient Hebrew swords

It appears that iron working in ancient Egypt developed from meteorites. The Guardian reported: “Although people have worked with copper, bronze and gold since 4,000 B.C., ironwork came much later, and was rare in ancient Egypt. In 2013, nine blackened iron beads, excavated from a cemetery near the Nile in northern Egypt, were found to have been beaten out of meteorite fragments, and also a nickel-iron alloy. The beads are far older than the young pharaoh, dating to 3,200 B.C. “As the only two valuable iron artifacts from ancient Egypt so far accurately analysed are of meteoritic origin,” Italian and Egyptian researchers wrote in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, “we suggest that ancient Egyptians attributed great value to meteoritic iron for the production of fine ornamental or ceremonial objects”. [Source: The Guardian, June 2, 2016]

“The researchers also stood with a hypothesis that ancient Egyptians placed great importance on rocks falling from the sky. They suggested that the finding of a meteorite-made dagger adds meaning to the use of the term “iron” in ancient texts, and noted around the 13th century B.C., a term “literally translated as ‘iron of the sky’ came into use … to describe all types of iron”. “Finally, somebody has managed to confirm what we always reasonably assumed,”Rehren, an archaeologist with University College London, told the Guardian. “Yes, the Egyptians referred to this stuff as metal from the heaven, which is purely descriptive,” he said. “What I find impressive is that they were capable of creating such delicate and well manufactured objects in a metal of which they didn’t have much experience.” The researchers wrote in the new study: “The introduction of the new composite term suggests that the ancient Egyptians were aware that these rare chunks of iron fell from the sky already in the 13th [century] B.C., anticipating Western culture by more than two millennia.” Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley, of the University of Manchester, has similarly argued that ancient Egyptians would have revered celestial objects that had plunged to earth. “The sky was very important to the ancient Egyptians,” she told Nature, apropos of her work on the meteoritic beads. “Something that falls from the sky is going to be considered as a gift from the gods.”

“It would be very interesting to analyse more pre-Iron Age artifacts, such as other iron objects found in King Tut’s tomb,” Daniela Comelli, of the physics department at Milan Polytechnic, told Discovery News. “We could gain precious insights into metal working technologies in ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean.”

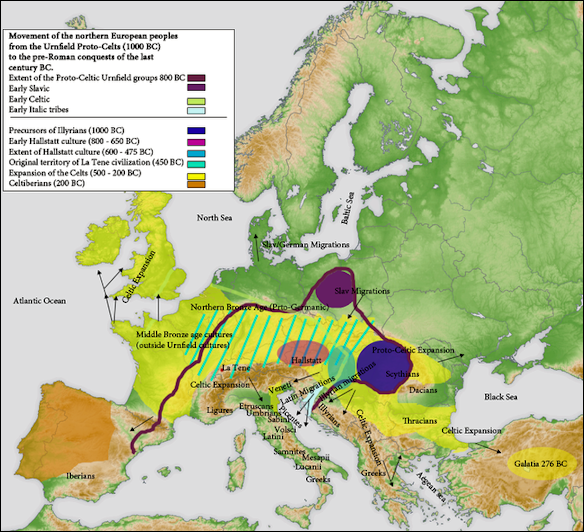

European migrations around 1000 BC

Iron Age Magnetism

Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: The Earth’s magnetic field helps protect the planet’s surface from the solar wind and cosmic rays. It’s not a static barrier, but rather a complex system generated by iron flowing in the Earth’s outer core. Every few hundred thousand years, the north and south magnetic poles “flip” position, and for the last 160 years, the magnetic field has been weakening. The causes of the reversals and weakening are unknown, but scientists are finding clues in the charred remains of Iron Age houses in southern Africa. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

“During the Iron Age, people there would, perhaps because of a bad harvest, ritually “cleanse” their villages by burning them down. The fires burned hot enough to melt magnetic materials in the clay. When those materials cooled and solidified, they were remagnetized by the magnetic field, recording its intensity and direction at that moment.

“Southern Africa lies within the South Atlantic Anomaly, a particularly weak patch in the magnetic field, larger than the United States. If it grows large enough, according to University of Rochester geophysicist John Tarduno, it could trigger a reversal of the poles. Understanding how the magnetic field, especially in southern Africa, has changed over time might help scientists better comprehend these processes, since there has not been much good historical data on the southern magnetic field. Because of Iron Age superstition, Tarduno and his colleagues now have a record of the anomaly for between 1,600 and 1,000 years ago.

“The findings show that during the Iron Age, the magnetic field was as it is today: weakening, with a big southern dent. The field has recovered to a degree since then, but is now weakening again. This suggests that there is some recurring disruption in the flow of the outer core that, like an eddy in a stream, comes and goes. If that eddy grows large enough, Tarduno says, a reversal might be imminent. Such a reversal could take thousands of years to be completed, and while the Earth would have some magnetic protection during this time, satellite communications, the ozone layer, and our power infrastructure would all be at some risk.

European Iron Age dwellings

Earliest Iron in China and India

The first iron in China dates to the Zhou period. The earliest iron foundry yet discovered in China was found in the Yangtze area. In May 2003, archeologists announced they found remains of an iron casting workshop along the Yangtze River, dating back to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 B.C.-256 B.C.) and the Qin Dynasty (221 -207 B.C.). Iron smelting technology is believed to have made its way to China via Scythian nomads in Central Asia around 8th century B.C.

In May 2003, the People’s Daily reported: “Archeologists in central China’s Hubei province have found remains of an iron casting workshop along the Yangtze River, dating back to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 B.C.-256 B.C.) and the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.-207 B.C.). The foundry remains, the first known from the Yangtze River, were unearthed at a highway construction site in Yaojiawan in Qiantang village of Xishui county. [Source: People’s Daily, May 27, 2003 -]

S. U. Deraniyagala Director-General of Archaeology, Sri Lanka wrote: The protohistoric Early Iron Age appears to have established itself in South India by at least as early as 1,200 B.C., if not earlier. The earliest manifestation of this in Sri Lanka is radiocarbon dated to ca. 1000-800 B.C. at Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya (Deraniyagala 1992:709-29; Karunaratne and Adikari 1994:58; Mogren 1994:39; the Anuradhapura dating is now corroborated by Coningham 1999). It is very likely that further investigations will push back the Sri Lankan lower boundary to match that of South India.

See Separate Article: ZHOU (CHOU) DYNASTY (1046 B.C. to 256 B.C.) factsanddetails.com ; FIRST HUMANS AND PREHISTORY OF SRI LANKA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024