FIRST IRON USED BY PEOPLE CAME FROM METEORITES

King Tut's dagger

Early people used meteorites to make iron weapons and jewelry way before anyone knew how to extract smelt iron and extract it from ore. In most cases, it isn’t known whether these cultures understood where meteorites came from.

Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: Since the early 2010s, studies of artifacts have confirmed that some civilizations used iron from meteorites to craft objects before smelted iron was available. In a cemetery on the Nile called Gerzeh, dated to about 5,200 years ago, archaeologists discovered nine beads made of meteoritic metal. An exquisitely made polished dagger and other meteoritic iron objects were among the treasures sealed in Tutankhamun’s tomb about 3,300 years ago. Ancient jewelry and weapons made from this rare material have also cropped up in other parts of the world: beads in North America, axes in China, and a dagger in Turkey. [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

By the time Tut’s dagger was made in the Late Bronze Age, artisans had learned to grind and polish the meteoritic metal into a fine blade. “It’s very sharp,” says Katja Broschat, a restorer at the Leibniz Center for Archaeology in Mainz, Germany, who has studied the artifact. “I’m sure you can kill an animal, or whatever, maybe even a man.” It would be roughly a thousand years before humans learned to reliably smelt iron.

History of Understanding Meteorites

Meteorites have struck the Earth since its earliest days as a planet. Every year, approximately 17,600 meteorites weighing more than 50 grams reach Earth. Most are primarily stone, but about 4 percent are iron-nickel alloys distinct from terrestrial iron. The Hoba meteorite outside of Grootfontein, Namibia, named after the farm where it was found, is the largest known meteorite. Estimated to weigh more than 67 tons, it sits where it landed less than 80,000 years ago, according to radioactive dating.

Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: The first dated account of a possible meteorite fall appears in the writings of ancient Greeks and Romans. Aristotle, Plutarch, and Pliny the Elder, among others, wrote about a stone landing in 467 or 466 B.C. in what is now Turkey. “It will not be doubted that stones do frequently fall,” Pliny observed. Plutarch also recounts a Roman military engagement in the first century B.C. that may have been interrupted by a meteorite. “As they were on the point of joining battle, with no apparent change of weather, but all on a sudden, the sky burst asunder, and a huge, flamelike body was seen to fall between the two armies,” he wrote. “In shape, it was most like a wine jar and in color, like molten silver.” [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

In 861, near a shrine in Nogata, Japan, according to oral traditions compiled in 1927, “a great detonation occurred,” “a brilliant flash was seen,” and “a black stone was found at the bottom of a newly made hole in the ground.” In 1983 Japanese scientists studied the meteorite, which is kept in an old wooden box inscribed with the year. After carbon-dating the container, they concluded the stone likely fell as described.

In Europe, though, until the beginning of the 19th century, most scientists had been skeptical that meteorites were a real phenomenon. In 1751 a meteorite landed in Hrašćina, Croatia, with witnesses reporting an explosion and a fireball in the sky — claims that were later dismissed as fairy tales. Weighing 88 pounds, the largest chunk of that meteorite is displayed in the Natural History Museum Vienna. In April 1794 German scientist Ernst Chladni published a book that compiled reports of stones and iron dropping from the sky — an endeavor that earned him ridicule. Then the cosmos intervened. In June 1794 a hail of rocks was seen by witnesses outside of Siena, Italy. The next year a 56-pound stone fell in Wold Cottage, England.

The impacts prompted English chemist Edward around Howard and French mineralogist Jacques-Louis de Bournon to collect samples from “fallen bodies.” Their analyses, published in 1802, showed that four stony meteorites had compositions and structures unlike terrestrial rocks. Howard also measured high nickel content in three iron meteorites and one stony-iron meteorite, revealing the metal was distinct from that smelted from ore. But it wasn’t until 1803 that the European scientific community was fully convinced of what Pliny seemed sure of. That year, a meteorite shower pelted L’Aigle, France, with about 3,000 stones.

With that, scientific interest in meteorites grew. English naturalist James Sowerby amassed a collection in his personal museum, including the Wold Cottage meteorite. He was so infatuated with them that he used a piece of an iron one found in South Africa to have a sword forged for Tsar Alexander I of Russia to commemorate the defeat of Napoleon in 1814. The inscription he had engraved on the blade begins: “This Iron, having fallen from the Heavens …”

Oldest Iron Found in Jewelry

Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: Whether or not they knew it came from the sky, ancient peoples valued meteoritic iron. Copper, silver, and gold exist in metallic form, available to be mined and worked, but on Earth, iron is almost always bound up with other elements, such as oxygen, in minerals called ores.

Iron Age jewelry

The oldest known objects fashioned from space metal were ornaments, such as the Gerzeh beads, some of which were strung along with gold and gemstones, including lapis lazuli, carnelian, and agate. “In the beginning it was used for precious things, beads and representative stuff, because it was so exotic,” says Broschat. “It took a while until the manufacturing technique … was good enough to produce a weapon or tool material.” [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

“When you start making smelted iron, it’s a big business, where you can be able to make weapons which are not expensive to produce,” says geochemist Albert Jambon, a professor emeritus at Sorbonne University in Paris. “There is a switch from one economy to a new economy.” Jambon has spent the past dozen years tracking down iron objects from the Bronze Age and analyzing them. His research brought him to Aleppo, Syria, where he examined a spherical iron pendant found in the ancient city of Umm el Marra, in a tomb dated to 2300 B.C. It was among a woman’s grave goods, which included beads of gold and stone and a piece of lapis lazuli carved into the figure of a goat, all of which may have dangled from a necklace. The museum in Aleppo also had a copper ax-head with an iron blade, dated to about 1400 B.C., discovered in the ruins of Ugarit, a port city. Jambon measured the chemical composition of these objects with a handheld x-ray fluorescence machine, which looks a bit like a ray gun. His analysis led him to conclude that both artifacts are meteoritic.

Difficulty of Working Out the First Iron

Jay Bennett wrote in National Geographic: How often people used sky metal has proved difficult to puzzle out. Hundreds of iron objects from Bronze Age sites are listed in archaeological records, but most have not been analyzed, and many are no more than small bits of rusted metal that may have been things like pins or rings. “If you look at what has already been excavated and how little of that even has been studied, that is a scandal,” says Thilo Rehren, an archaeological scientist at the Cyprus Institute. Like many archaeologists, Rehren is interested in distinguishing between meteoritic and smelted iron, not necessarily to discover celestial metal but to figure out how and where the Iron Age began. [Source: Jay Bennett, National Geographic, May 9, 2023]

Civilizations in West Asia and the Caucasus Mountains began making bronze as early as the fourth millennium B.C. But most experts believe humans would not learn to reliably extract iron from ore until the end of the second millennium B.C. Smelting iron requires temperatures of roughly 2,200 degrees Fahrenheit. “When you start making smelted iron, it’s a big business, where you can be able to make weapons which are not expensive to produce,” says geochemist Albert Jambon, a professor emeritus at Sorbonne University in Paris. “There is a switch from one economy to a new economy.”

Jambon has been in Nicosia, Cyprus, where he has been studying the island’s extensive collection of early iron artifacts, which date to about 1200 B.C. This presents something of a mystery, considering the island does not have any typical iron ores, such as magnetite and hematite. In a dusty storeroom of the Cyprus Museum, Jambon used his x-ray gun and a small magnifying glass to examine dozens of iron artifacts. “Ooh là là,” he murmured as he saw the first one, the end of a sickle. “C’est vraiment bien.” Despite his excitement, these artifacts weren’t likely to be displayed. Iron rusts when exposed to oxygen, unlike bronze, which develops a green patina, or gold, which does not oxidize at all. Next to well-preserved treasures, corroding metal does not appear so striking. And none, it seemed, were made of meteoritic metal. Most were knives, but a spiral ring and a brooch served as a reminder that even after iron smelting began, the metal was considered precious.

Iron and the Hitittes

The Hittites are regarded as the first people to produce iron and thus are the civilization that ushered in the Iron Age. About 1200 B.C., scholars suggest, cultures other than the Hittites began to possess iron. The Assyrians began using iron weapons and armor in Mesopotamia around that time with deadly results, but the Egyptians did not utilize the metal until the later pharaohs. Lethal Celtic iron swords dating back to 950 BC have been found in Austria and its is believed the Greeks learned to make iron weapons from them.

Iron was made around 1500 B.C. by the Hitittes. About 1400 B.C., the Chalbyes, a subject tribe of the Hitittes invented the cementation process to make iron stronger. The iron was hammered and heated in contact with charcoal. The carbon absorbed from the charcoal made the iron harder and stronger. The smelting temperature was increased by using more sophisticated bellows.

The Hittites mined iron in the Black Sea region. Hittite Iron mines supplied the region with metal. Metal making secrets were carefully guarded by the Hittites and the civilizations in Turkey, Iran and Mesopotamia. Iron could not be shaped by cold hammering (like bronze), it had to be constantly reheated and hammered. The best iron has traces of nickel mixed in with it.

See Separate Article: HITTITES AND IRON africame.factsanddetails.com

Iron-Making First Achieved in Africa?

The generally accepted view is that Iron smelting was first developed by the Hittites, an ancient people that lived in what is now Turkey, around 1500 B.C.. Some scholars argue that iron-making was developed around the same time by Africans in Termit, Niger around 1500 B.C. and perhaps even earlier at other places in Africa, notably Central African Republic.

A 2002 UNESCO published study suggested that iron smelting at Termit, in eastern Niger may have begun as early as 1500 B.C.. This finding, which would be of great importance to both the history of Niger and the history of the diffusion of Iron Age metalworking technology in all of sub-Saharan Africa, is as yet contentious. Older accepted studies place the spread of both copper and Iron technology to date from the early first Millennium CE: 1500 years later than the Termit Massif finds

7th century BC iron swords from Italy

According to the 2002 UNESCO report: “Africa developed its own iron industry some 5,000 years ago, according to a formidable new scientific work from UNESCO Publishing that challenges a lot of conventional thinking on the subject.iIron technology did not come to Africa from western Asia via Carthage or Merowe as was long thought, concludes "Aux origines de la métallurgie du fer en Afrique, Une ancienneté méconnue: Afrique de l'Ouest et Afrique centrale". The theory that it was imported from somewhere else, which - the book points out - nicely fitted colonial prejudices, does not stand up in the face of new scientific discoveries, including the probable existence of one or more centres of iron-working in west and central Africa andthe Great Lakes area. [Source: Jasmina Sopova, Bureau of Public Information, The Iron Roads Project. Launched by UNESCO in 1991 as part of the World Decade for Cultural Development (1988-97)]

Heather Pringle wrote in Science ““Some of the most important sites in Africa supporting very early evidence for the invention of iron in Africa include Termit in East Niger, yielding dates as early as 1500 B.C.; The Air Mountains also in Niger yield very early dates for copper metallurgy as early as 3000--2500 B.C.. And in Nigeria there is also the Nok Culture yielding dates as early as 900 B.C. ( and according to Cheik Anta Diop and others, even later) for iron. In the great Lakes region associated with Urewe Ceramic culture the dates are estimated to be as early as 1450–500 B.C. for iron technology. [Source: Heather Pringle, "Seeking Africa's First Iron Men", Science January 9, 2009: Vol. 323 no. 5911 pp. 200-202]

Iron-Making First Achieved in Central Africa, 4000 Years Ago?

Heather Pringle wrote in Science “ “Controversial findings from a French team working at the site of boui in the Central African Republic challenge the diffusion model. Artifacts there suggest that sub-Saharan Africans were making iron by at least 2000 B.C.E. and possibly much earlier — well before Middle Easterners, says team member Philippe Fluzin, an archaeometallurgist at the University of Technology of Belfort-Montbliard in Belfort, France. The team unearthed a blacksmith's forge and copious iron artifacts, including pieces of iron bloom and two needles, as they describe in a recent monograph, Les Ateliers d'boui, published in Paris. "Effectively, the oldest known sites for iron metallurgy are in Africa," Fluzin says. Some researchers are impressed, particularly by a cluster of consistent radiocarbon dates. Others, however, raise serious questions about the new claims. [Source: Heather Pringle, "Seeking Africa's First Iron Men", Science January 9, 2009: Vol. 323 no. 5911 pp. 200-202]

“The authors of this joint work, which is part of the "Iron Roads in Africa" project, are distinguished archaeologists, engineers, historians, anthropologists and sociologists. As they trace the history of iron in Africa, including many technical details and discussion of the social, economic and cultural effects of the industry, they restore to the continent "this important yardstick of civilisation that it has been denied up to now," writes Doudou Diène, former head of UNESCO's Division of Intercultural Dialogue, who wrote the book's preface.

“But the facts speak for themselves. Tests on material excavated since the 1980s show that iron was worked at least as long ago as 1500 BC at Termit, in eastern Niger, while iron did not appear in Tunisia or Nubia before the 6th century BC. At Egaro, west of Termit, material has been dated earlier than 2500 BC, which makes African metalworking contemporary with that of the Middle East.

“The roots of metallurgy in Africa go very deep. However, French archaeologist Gérard Quéchon cautions that "having roots does not mean they are deeper than those of others," that "it is not important whether African metallurgy is the newest or the oldest" and that if new discoveries "show iron came from somewhere else, this would not make Africa less or more virtuous." "In fact, only in Africa do you find such a range of practices in the process of direct reduction [a method in which metal is obtained in a single operation without smelting],and metal workers who were so inventive that they could extract iron in furnaces made out of the trunks of banana trees," says Hamady Bocoum, one of the authors.

Iron Working in Ancient Egypt Developed from Meteorites

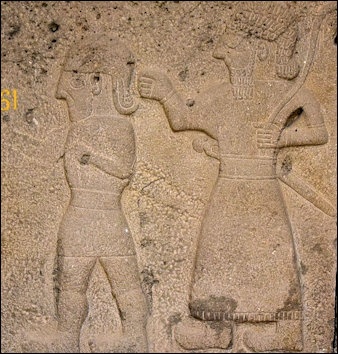

9th century BC depiction of men with swords from the Hittite city of Sam'al

It appears that iron working in ancient Egypt developed from meteorites. The Guardian reported: “Although people have worked with copper, bronze and gold since 4,000 B.C., ironwork came much later, and was rare in ancient Egypt. In 2013, nine blackened iron beads, excavated from a cemetery near the Nile in northern Egypt, were found to have been beaten out of meteorite fragments, and also a nickel-iron alloy. The beads are far older than the young pharaoh, dating to 3,200 B.C. “As the only two valuable iron artifacts from ancient Egypt so far accurately analysed are of meteoritic origin,” Italian and Egyptian researchers wrote in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science, “we suggest that ancient Egyptians attributed great value to meteoritic iron for the production of fine ornamental or ceremonial objects”. [Source: The Guardian, June 2, 2016]

“The researchers also stood with a hypothesis that ancient Egyptians placed great importance on rocks falling from the sky. They suggested that the finding of a meteorite-made dagger adds meaning to the use of the term “iron” in ancient texts, and noted around the 13th century B.C., a term “literally translated as ‘iron of the sky’ came into use … to describe all types of iron”. “Finally, somebody has managed to confirm what we always reasonably assumed,”Rehren, an archaeologist with University College London, told the Guardian. “Yes, the Egyptians referred to this stuff as metal from the heaven, which is purely descriptive,” he said. “What I find impressive is that they were capable of creating such delicate and well manufactured objects in a metal of which they didn’t have much experience.”

The researchers wrote in the new study: “The introduction of the new composite term suggests that the ancient Egyptians were aware that these rare chunks of iron fell from the sky already in the 13th [century] B.C., anticipating Western culture by more than two millennia.” Egyptologist Joyce Tyldesley, of the University of Manchester, has similarly argued that ancient Egyptians would have revered celestial objects that had plunged to earth. “The sky was very important to the ancient Egyptians,” she told Nature, apropos of her work on the meteoritic beads. “Something that falls from the sky is going to be considered as a gift from the gods.”

“It would be very interesting to analyse more pre-Iron Age artifacts, such as other iron objects found in King Tut’s tomb,” Daniela Comelli, of the physics department at Milan Polytechnic, told Discovery News. “We could gain precious insights into metal working technologies in ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean.”

Did Africans Invent Steel 1,900 Years before Europeans?

The Haya people on the western shore of Lake Victoria in Tanzania made medium-carbon steel in preheated, forced-draft furnaces between 1,500 and 2,000 years ago. The person usually given credit with inventing steel is German-born metallurgist Karl Wilhelm who used an open hearth furnace in the 19th century to make high grade steel. The Haya made their own steel until the middle of the middle 20th century when they found it was easier to make money from raising cash crops like coffee and buy steel tools from the Europeans than it was to make their own. [Source: Time magazine, September 25, 1978]

The discovery was made by anthropologist Peter Schmidt and metallurgy professor Donald Avery, both of Brown University. Very few of the Haya remember how to make steel but the two scholars were able to locate one man who made a traditional ten-foot-high cone shaped furnace from slag and mud. It was built over a pit with partially burned wood that supplied the carbon which was mixed with molten iron to produce steel. Goat skin bellows attached to eight ceramic tubs that entered the base of the charcoal-fueled furnace pumped in enough oxygen to achieve temperatures high enough to make carbon steel (3275 degrees F).

While doing excavations on the western shore of Lake Victoria Avery found 13 furnace nearly identical to the one described above. Using radio carbon dating he was astonished to find that the charcoal in the furnaces was between 1,550 and 2,000 years old.

John H. Lienhard at the University of Houston wrote: “The Hayas made their steel in a kiln shaped like a truncated upside-down cone about five feet high. They made both the cone and the bed below it from the clay of termite mounds. Termite clay makes a fine refractory material. The Hayas filled the bed of the kiln with charred swamp reeds. They packed a mixture of charcoal and iron ore above the charred reeds. Before they loaded iron ore into the kiln, they roasted it to raise its carbon content. The key to the Haya iron process was a high operating temperature. Eight men, seated around the base of the kiln, pumped air in with hand bellows. The air flowed through the fire in clay conduits. Then the heated air blasted into the charcoal fire itself. The result was a far hotter process than anything known in Europe before modern times.

“Schmidt wanted to see a working kiln, but he had a problem. Cheap European steel products reached Africa early in this century and put the Hayas out of business. When they could no longer compete, they'd quit making steel. Schmidt asked the old men of the tribe to recreate the high tech of their childhood. They agreed, but it took five tries to put all the details of the complex old process back together. What came out of the fifth try was a fine, tough steel. It was the same steel that'd served the subsaharan peoples for two millinea before it was almost forgotten.

Ancient Hebrew swords

Bronze Age People Made Tempered Steel 2,900 Years Ago

Steel is considered by many to be one of the great Industrial Age inventions, but it turns out some inhabitants of Iberia were capable of forging tempered steel tools 2,900 years ago. Metallographic analysis of a chisel from Rocha do Vigio, Portugal determined that it is made of carbon-rich steel. This durable material was used to carve stone stelas featuring complex anthropomorphic and geometric motifs. The local silicated quartz sandstone was too hard for stone, bronze, or iron chisels.[Source: Archaeology magazine, May 2023]

Sascha Pare wrote in Live Science: An intricate 2,900-year-old engravings on stone monuments from what is now Portugal could only have been made using steel instruments, archaeologists have found. The discovery hints at small-scale steel production during the Final Bronze Age, a century before the practice became widespread in ancient Rome.

The 5-foot-tall (1.5 meters) rock pillars, or stelae, are made of silicate quartz sandstone and feature carvings of human and animal figures, weapons, ornaments and chariots. "This is an extremely hard rock that cannot be worked with bronze or stone tools," Ralph Araque Gonzalez, an archaeologist at the University of Freiburg in Germany and lead author of a new study describing the findings, said in a statement. "The people of the Final Bronze Age in Iberia were capable of tempering steel. Otherwise they would not have been able to work the pillars." Tempering is the process of heat-treating steel to make it harder and more resistant to fracturing. [Source: Sascha Pare, Live Science, March 9, 2023]

The team also analyzed an "astoundingly well preserved" iron chisel that dates to around 900 B.C. and was unearthed in the early 2000s from Rocha do Vigio, the researchers wrote in the study, published online February 10, 2023 in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Not only did the chisel contain enough carbon to be considered steel (more than 0.30 percent), but the researchers also found iron mineralization within the settlement site, suggesting that craftspeople may have sourced the material locally. "The chisel from Rocha do Vigio and the context where it was found show that iron metallurgy, including the production and tempering of steel, were probably indigenous developments of decentralized small communities in Iberia, and not due to the influence of later colonization processes," Araque Gonzalez said.

The researchers worked with a professional stonemason to imitate the ancient engravings with tools made from different materials, including bronze, stone and a tempered steel replica of the 2,900-year-old chisel. The steel instrument was the only one able to carve the rock, according to the study. A blacksmith had to sharpen it every five minutes, however, which suggests craftspeople from the Final Bronze Age knew how to make carbon-rich, hardened steel. The team also noted that the experimental carvings were remarkably similar to the original ones if they accounted for rock weathering.

Up until now, the earliest record of hardened steel in Iberia was from the Early Iron Age (800 to 600 B.C.). Widespread steel production for weapons and tools probably only began during Roman times, around the second century A.D., although the low carbon content of excavated objects points to their mediocre quality. It wasn't until the late medieval period that blacksmiths across Europe learned how to achieve high enough temperatures to make good quality steel.

3,000-Year-Old Swiss Arrowhead Made from a Meteorite 1,000 Kilometers Away

A three-centimeter-long, 3,000-year-old arrowhead found Mörigen, Switzerland was made of meteoritic iron. Perhpas just as unusual as the arrowhead itself is the fact the meteor did not fall to earth in the same area of Switzerland. Scientists believe it may instead have come from meteor site nearly 1,000 kilometers (600 miles) away. [Source: Mia Jankowicz, Business Insider, August 9, 2023]

According to Business Insider: The 1.5-inch arrowhead was found during a 19th-century excavation of a Bronze Age settlement near Mörigen in eastern Switzerland, according to the Natural History Museum of Bern. The site is two miles away from the debris field of a meteorite known as the Twannberg meteorite — prompting scientists to ask whether it was made of the same space metal. However, after extensive testing, scientists announced this month that the metal is indeed meteoritic — but that it's not from Twannberg. According to their findings, the nickel content of the arrowhead is about twice as high as metal from the local meteorite debris.

Instead, they wrote, the most likely origin is a lake formed by a meteor nearly 600 miles away in Estonia — a theory they said needs to be studied further. "This large craterforming fall event happened at [roughly] 1500 years B.C. during the Bronze Age and produced many small fragments," the study said.

One such fragment may have traveled all the way to Mörigen, lead study author Beda Hofmann told CNN. "Trade across Europe during the Bronze Age is a well-established fact: Amber from the Baltic (like the arrowhead, presumably), tin from Cornwall, glass beads from Egypt and Mesopotamia," he said by email.

Before humans knew how to smelt iron from oxide ores, they were making use of iron from meteorites, according to the study about the arrowhead. However, "evidence of such early use of meteoritic iron is extremely rare," the Bern museum said in a statement. Only 55 ancient meteoritic objects have been discovered across Eurasia and Africa. Nineteen of these were found in King Tutankhamun's tomb, according to the museum.

European Iron Age dwellings

Earliest Iron in China

The first iron in China dates to the Zhou period. The earliest iron foundry yet discovered in China was found in the Yangtze area. In May 2003, archeologists announced they found remains of an iron casting workshop along the Yangtze River, dating back to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 B.C.-256 B.C.) and the Qin Dynasty (221 -207 B.C.). Iron smelting technology is believed to have made its way to China via Scythian nomads in Central Asia around 8th century B.C.

In May 2003, the People’s Daily reported: “Archeologists in central China’s Hubei province have found remains of an iron casting workshop along the Yangtze River, dating back to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 B.C.-256 B.C.) and the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.-207 B.C.). The foundry remains, the first known from the Yangtze River, were unearthed at a highway construction site in Yaojiawan in Qiantang village of Xishui county. [Source: People’s Daily, May 27, 2003 -]

“An excavation layer 150-250 centimeters thick contained numerous red pottery sherds and fragments of molds, red soil furnace walls, cinders, slag, and various forms of casting tools, according to Wu Xiaosong, curator of the Huanggang Municipal Museum. He noted that iron was first widely used in central China in making farming instruments and weaponry. Researchers from Beijing University of Science and Technology and the Chinese University of Science and Technology found that the molds were used in making everyday iron appliances such as kettles. Archaeologists are exploring residential and burial sites around the iron casting workshops, seeking further information on ancient iron casting process and crafts. -

See Separate Article: ZHOU (CHOU) DYNASTY (1046 B.C. to 256 B.C.) factsanddetails.com

Early Iron Age in India and 2300-Year-Old Advanced Steel from Sri Lanka

S. U. Deraniyagala Director-General of Archaeology, Sri Lanka wrote: The protohistoric Early Iron Age appears to have established itself in South India by at least as early as 1,200 B.C., if not earlier. The earliest manifestation of this in Sri Lanka is radiocarbon dated to ca. 1000-800 B.C. at Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya (Deraniyagala 1992:709-29; Karunaratne and Adikari 1994:58; Mogren 1994:39; the Anuradhapura dating is now corroborated by Coningham 1999). It is very likely that further investigations will push back the Sri Lankan lower boundary to match that of South India.

Some of the earliest evidence of steel making in the ancient world, dating back to 300 B.C., has been found in the Samanalawewa reservoir area. John Noble Wilford wrote in the New York Times: “Every year from June to September, powerful monsoon winds blow steadily off the Indian Ocean, lashing the slopes of the hills and ridges of Sri Lanka facing the southwest. The winds dump torrents of rain on parts of the country, while leaving the rest blow-dried. In the dry region of Samanalawewa, archeologists have found surprising evidence that the monsoon was a driving force stoking South Asia's pre-eminence in steel production in the first millennium A.D. [Source: John Noble Wilford, New York Times, February 6, 1996]

“British and Sri Lankan archeologists have identified there the ruins of 41 iron-smelting furnaces that appeared to take advantage of the prevailing wind to produce high-carbon steel through a previously unknown technology. Tests with replicas of those furnaces revealed the principle underlying the technology — using natural wind-pressure to create a dependable draft for keeping charcoal fires smelting hot — and demonstrated its ability to produce substantial amounts of quality steel.

See Separate Article: FIRST HUMANS AND PREHISTORY OF SRI LANKA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024