WAR AND EARLY MODERN HUMANS

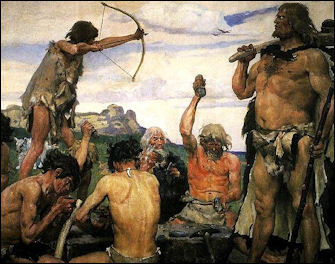

Saharan art Warfare — defined as organized group combat as opposed to acts of individual violence — is thought to have evolved around the time agriculture and villages developed, with idea that it became necessary when there was turf to defend, covet and fight over. Dr. Steven A LeBlanc of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard and author of a book called “Constant Battles,” told the New York Times, “War is universal and goes back deep into human history” and it is a myth that once people were “sublimely peaceful."

E. O. Wilson wrote: “Tribal aggressiveness goes back well beyond Neolithic times, but no one as yet can say exactly how far. It could have begun at the time of Homo habilis, the earliest known species of the genus Homo, which arose between 3 million and 2 million years ago in Africa. Along with a larger brain, those first members of our genus developed a heavy dependence on scavenging or hunting for meat. And there is a good chance that it could be a much older heritage, dating beyond the split 6 million years ago between the lines leading to modern chimpanzees and to humans. [Source: E. O. Wilson, Discover, June 12, 2012 /*/]

“Archaeologists have determined that after populations of Homo sapiens began to spread out of Africa approximately 60,000 years ago, the first wave reached as far as New Guinea and Australia. The descendants of the pioneers remained as hunter-gatherers or at most primitive agriculturalists, until reached by Europeans. Living populations of similar early provenance and archaic cultures are the aboriginals of Little Andaman Island off the east coast of India, the Mbuti Pygmies of Central Africa, and the !Kung Bushmen of southern Africa. All today, or at least within historical memory, have exhibited aggressive territorial behavior. *\

“History is a bath of blood,” wrote William James, whose 1906 antiwar essay is arguably the best ever written on the subject. “Modern man inherits all the innate pugnacity and all the love of glory of his ancestors. Showing war’s irrationality and horror is of no effect on him. The horrors make the fascination. War is the strong life; it is life in extremis; war taxes are the only ones men never hesitate to pay, as the budgets of all nations show us.” *\

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Constant Battles: The Myth of the Peaceful, Noble Savage” by Steven Le Blanc and Katherine E. Register (2003) Amazon.com;

“Warless Societies and the Origin of War” by Raymond C. Kelly (2000) Amazon.com;

“The Archaeology of Warfare: Prehistories of Raiding and Conquest

by Elizabeth N. Arkush and Mark W. Allen (2006) Amazon.com;

“Massacres: Bioarchaeology and Forensic Anthropology Approaches” by Cheryl P. Anderson and Debra L. Martin (2018) Amazon.com;

“War Before Civilization: The Myth of the Peaceful Savage” by Lawrence H. Keeley (1997) Amazon.com;

“Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times” by Thomas Wilson (2022) Amazon.com

“A View to a Kill: Investigating Middle Palaeolithic Subsistence Using an Optimal Foraging Perspective” (2008) by G. L. Dusseldorp Amazon.com

“Meat-Eating and Human Evolution” by Craig B. Stanford, Henry T. Bunn Amazon.com;

“The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“The Social Conquest of Earth” by Edward O. Wilson (2013) Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

Early Evidence of Warfare

The earliest evidence of war comes from a grave in the Nile Valley in Sudan. Discovered in the mid-1960s and dated to be between 12,000 and 14,000 years old, the grave contains 58 skeletons, 24 of which were found near projectiles regarded as weapons. The victims died at a time the Nile was flooding, causing a severe ecological crisis. The site, known as Site 117, is located at Jebel Sahaba in Sudan. The victims included men, women and children who died violently. Some were found with spear points in near the head and chest that strongly suggest they were not offering but weapons used to kill the victims. There is also evidence of clubbing — crushed bones an the like. Since there were so many bodies, one archaeologist surmised, "It looks like organized, systematic warfare." [Source: History of Warfare by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Nataruk, a 10,000-year-old site in Kenya, contains the earliest known evidence of inter-group conflict. Sarah Kaplan wrote in the Washington Post: “The skeletons told an alarming tale: One belonged to a woman who died with her hands and feet bound. The hands, chest and knees of another were fragmented and fractured — likely evidence of having been beaten to death. Stone projectiles protruded ominously from skulls; razor-sharp obsidian blades glittered in the dirt. [Source: Sarah Kaplan, Washington Post, April 1, 2016 \=]

“The grotesque tableau, discovered in Nataruk, Kenya, is the oldest known evidence of prehistoric warfare, scientists said in the journal Nature earlier this year. The scattered, scrambled remains of 27 men, women and children seemed to illustrate that conflict is not simply a symptom of our modern sedentary societies and expansionist ambitions. Even when we existed in isolated bands roaming across vast, unsettled continents, we showed capacity for hostility, violence and barbarism. One of the members of the “Nataruk Group” was a pregnant woman; inside her skeleton, scientists found her fetus’s fragile bones.” \=\

“The deaths at Nataruk are testimony to the antiquity of inter-group violence and war,” lead author Marta Mirazon Lahr, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. She told Smithsonian, “What we see at the prehistoric site of Nataruk is no different from the fights, wars and conquests that shaped so much of our history, and indeed sadly continue to shape our lives.”“\=\

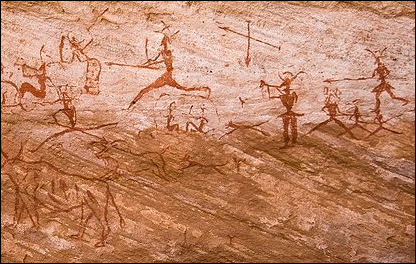

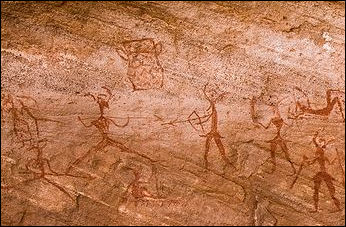

A site in northern Iraq, dated to 10,000 years ago, contains maces and arrowheads found with skeletons and defensive walls — thought to evidence of early warfare. Forts, dated to 5000 B.C., have been found in southern Anatolia. Other early evidence of war includes: 1) a battle scene, dated to between 4300 and 2500 B.C., with groups of men firing bows and arrow at each other in a rock painting in Tassili n’Ajjer, a Saharan plateau in southeastern Algeria; 2) a pile of decapitated human skeletons, dated to 2400 B.C., found at the bottom of a well near Handan, China, 250 miles southwest of Beijing; 3) paintings, dated to 5000 B.C., of an execution, found in a cave in Remigia cave, and a clash between archers from Morella la Vella in eastern Spain.

Murder and Bravery and Early Modern Humans

Saharan art One of the first pieces of evidence of man killing man is from a site in the Nile Valley north of Aswan called Wadi Kubbaniya. There a 20,000-year-old male skeleton was found with two broken arms, two spear points imbedded in the pelvic bone and a spear point embedded in the upper arm surrounded by partly healed bone. The bones date back to a period when the flow the Nile was less than what it is today, an event that may have resulted in widespread famine.

According to Archaeology magazine: In 1941, when a 33,000-year-old human skull was discovered in southern Transylvania’s Cioclovina Cave, it was recognized as the remains of one of the earliest modern humans in Europe. New research suggests it is also evidence of a Paleolithic murder. Forensic investigation and experimental simulation concluded that two fractures on the skull were inflicted premortem, and not postmortem as originally thought. The individual appears to have been killed by bluntforce trauma to the head with a club-like object wielded by a left-handed suspect. [Source: Archaeology magazine, September-October 2019]

Some scholars have asked why early modern humans were willing to show courage and bravery in war and risk their lives when it goes against the desire to stay alive and reproduce. Research on the subject by Laurent Lehmann and Marcy Feldman of Stanford University suggests that great bravery can have evolutionary benefits under certain circumstances and courage make its more likely that small bands of tribesmen will win clashes over their rivals, with the understanding that some individual may die but survivors may father more offspring and claim more land to help their community grow by winning more battles and raping and pillaging.

Going along with this is the idea that women prefer brave warriors. But anthropologists say that is not always the case, Until missionaries arrived in 1958, the Waorani tribe of Ecuador had the highest murder rates ever known in science: 39 percent of the women and 54 percent of the men were killed by Waorani, often in blood feuds that lasted for generations. Stephen Beckerman, an anthropologist at Pennsylvania State University and author of a study on the subject told Newsweek, “The conventional wisdom has been that the more raids a man participates in, the more wives he would have and the more descendants he would leave." At least with Waorani that turns out not to true. “The badass guys make terrible husband material. Women don't prefer them as husbands and they became targets of couterraids, which often kill the wives and children too."

Maba Man: Evidence of Foul Play and Caring Among Ancient Man?

A cracked skull found in China may be the oldest known evidence of interpersonal aggression among modern humans, Archaeology magazine reported. A CT scan of the skull, which is around 130,000 years old and known as Maba Man, revealed evidence of severe blunt force trauma, possibly from a clubbing. Remodeling of the bone around the injury, however, shows that he survived the blow and possibly was well cared for after his injury — for months or even years. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March-April 2012, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Science]

Jennifer Welsh wrote in LiveScience: “The Maba Man skull pieces were found in June 1958 in a cave in Lion Rock, near the town of Maba, in Guangdong province, China. They consist of some face bones and parts of the brain case. From those fragments, researchers were able to determine that this was a pre-modern human, perhaps an archaic human. He (or she, since researchers can't tell the sex from the skull bones) would have lived about 200,000 years ago, according to researcher Erik Trinkaus, of Washington University in St. Louis. [Source: Jennifer Welsh, LiveScience, November 21, 2011, based on study published November 21, 2011 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences]

Decades after the skull bones were discovered, researcher Xiu-Jie Wu at the Chinese Academy of Sciences took a close look at the strange formations on the left side of the forehead, using computed tomography (CT) scans and high-resolution photography. The skull has a small depression, about half an inch long and circular in nature. On the other side of the bone from this indentation, the skull bulges inward into the brain cavity. After deciding against any other possible cause of the bump, including genetic abnormalities, diseases and infections, they were left with the idea that Maba somehow hit his head. The certainties stop there, though. The researchers suggest that all they really know is the ancient human suffered a blow to the head.

"What becomes much more speculative is what ultimately caused it," Trinkaus said. "Did they get in an argument with someone else, and they picked something up and hit them over the head?" Based on the size of the indentation and the force needed to cause such a wound, it's possible it was another hominid, Trinkaus said. "This wound is very similar to what is observed today when someone is struck forcibly with a heavy blunt object," said study researcher Lynne Schepartz, from the school of anatomical sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand, adding that it "could possibly be the oldest example of interhuman aggression and human-induced trauma documented." Another possibility: Maba might have had a run-in with an animal. A deer antler would be about the right size to make the forehead mark, though the researchers don't know if it would be forceful enough to crack Maba's skull.

After the whack on the head, Maba shows considerable healing, suggesting he survived the hit. It could have been months or even years later that he would have died, of some other cause. These hominids lived in groups and Maba would have been taken care of by his group mates. Though nonlethal, the injury likely would have given Maba some memory loss, the researchers said. "This individual, which was an older adult, received a very localized, hard whack on the head," Trinkaus said. "It could have caused short-term amnesia, and certainly a serious headache."

"Our conclusion is that most likely, and this is a probabilistic statement, [the injury] was caused by another person," Trinkaus told LiveScience. “People are social mammals, we do these kinds of things to each other. Ultimately all social animals have arguments and occasionally whack another and cause injury...It's another case of long-term survival of a pretty serious injury."

Human Murder of a Neanderthal?

Saharan art There is some circumstantial evidence that Neanderthals were murdered by modern humans. A skull and bones from El Sidron cave in Spain are marked by jagged edges, which Antonio Rosas of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid believes were made blows from stone tools of modern humans.

The skeleton of Neanderthal male found at Shanidar, who lived sometime between 50,000 and 75,000 years, had a broken rib that indicated he had been struck in rib and died of a collapsed lung one to three weeks later. Some researchers argued that this was evidence of a man being stabbed to death or being badly beaten up by another Neanderthal, but others say the wounds could just as easily been caused by an accident.

That is until Duke anthropologist Steven Churchill published a study in July 2009 that used modern forensic science and determined that the victim, known to scientists as Shanidar 3 after the Iraq site, was most likely killed by a thrown spear. What is perhaps even more remarkable about the finding is that at that time only humans had throwing spears, a technology that makes sense in open grassland of Africa, while Neanderthals used only thrusting spears.

In an experiment Churchill's team aimed to re-create the conditions of Shanidar 3's death using a crossbow, Stone Age projectiles and a pig carcass (pig skin and bones are thought to have the same toughness as Neanderthal skin and bones). When the projectiles were fired at a velocity consistent with that of a thrown spear the punctures left on the pig's ribs resembled those found on the Shanidar 3's ribs. By contrast when the ribs were stabbed with a thrusting spear Churchill found the ribs “were busted al to hell. The high kinetic energy cased a lot of damage on the area." In addition, the angle of entry of Shanidar 3's wound is “consistent with the ballistic trajectory of a thrown weapon."

This isn't the only evidence of the murder of Neanderthals by humans. A skull and bones from El Sidron cave in Spain were found with jagged edges, which Antonio Rosas of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid believes were made by blows from stone tools of modern humans. A Neanderthal jawbone found by French anthropologist Fernando Rozzi bore butchering marks like those found on deer carcasses butchered by humans. He says that humans probably removed and ate the Neanderthal tongue and used the teeth for decorative ornaments.

Early Modern Human Weapons

Unlike Neanderthals who attacked their prey directly and relied on thrusting spears for hunting at close quarters, modern humans hunted at a distance with spear throwers that were effective from 30 to 50 feet away. These were tipped by a variety of carefully wrought stone and bone points. The throwing spears used by modern humans made hunting more efficient and less dangerous. At the 20,000-year-old Sungir site in Russia archaeologist unearthed 11 dartlike spears, three daggers and two long spear. One of the spears was 8-feet-long and had a point fashioned from a mammoth tusk.

The earliest weapons on record are spears with stone points dating to 460,000 years and found in southern Africa. Between 400,000 and 380,000 years ago, when the early human relatives Homo heidelbergensis lived in Europe, wooden spears shaped from branches of spruce and pine trees were used in Europe. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Recent research has shown that later hunters were able to kill their animal prey at a distance with spears: For instance, a study of the wounds on deer bones found at Neanderthal hunting sites show that the spears were thrown at their prey from several feet away, instead of being used in an attack at close quarters. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]

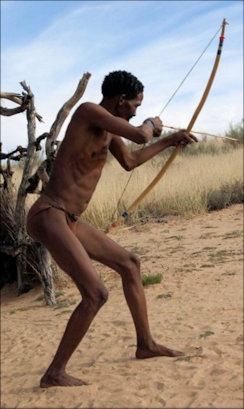

At some point modern humans also invented primitive bow and arrows which are deadly from distance of around 100 feet. The bow is regarded by some as the first machine since it had moving parts and converted musculature energy to mechanical energy. Hunting weapons like spears and arrows saw big changes from the specialization of tools in the Upper Paleolithic period (50,000 to 10,000 years ago). As the shaping of bones and antlers became common, they were formed into spear points, arrowheads, harpoons and fishhooks — often highly decorated, and with intricate rows of barbs to prevent them from being shaken loose by fleeing prey. Antler spear points dated to between 19,000 and 11,000 years ago have been found in southwest France.

Twelve-thousand-year-old cave art in Altira Spain shows men with bows, perform outflanking movement. By 10,000 years ago modern humans were using maces (derived from club) and slings (derived from bolas, which wrapped around legs of animals). These tools and bows and arrows marked difference between old stone age (Paleolithic period) and new stone age (Neolithic period). [Source: History of Warfare by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

See Separate Article: EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING: WITH BOWS, ARROWS AND ATLATLS europe.factsanddetails.com

Did Advanced Weaponry Give Early Humans Edge over Neanderthals?

Discovery of sharpened stone blades up to 71,000 years old suggests humans leaving Africa were armed with advanced weapons and this may have played a role in the demise of the Neanderthals. The stone blades would have allowed early humans ancestors to attack Neanderthals — and other humans — from a greater distance and with more devastating effect, researchers say. [Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian, November 7, 2012 |=|]

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “Early humans wandered out of Africa armed with darts and arrows that made them formidable hunters and deadly competitors for any Neanderthals that stood in their way. The revised version of the human story follows the discovery in South Africa of a haul of small stone blades or "bladelets" that formed lethal weapon tips, either for arrows fired from bows, or spears propelled from wooden throwers called atlatls. Researchers uncovered more than 70 sharp stone tips measuring no more than 5 centimeters long while excavating an eroded cliff face that overlooks the ocean at a site called Pinnacle Point on the south coast. |=|

“The development of the technology allowed early humans to attack wild animals or human foes from a greater distance and with more devastating effect. "People who possess light armaments that can be thrown long distances have immediate advantages in hunting prey and killing competitors," Curtis Marean, project director at Arizona State University, told the Guardian.

“The blades were made from a rock called silcrete that must be heated in fire to transform it into a material that can be flaked into a sharp edge. Long, thin flakes of stone were notched and snapped to make smaller tips, and then blunted on one side so they could be fixed into lengths of wood or bone to make a spear or dart. Tests on the stone tools found at Pinnacle Point revealed they were made throughout a period lasting from 71,000 to 60,000 years ago, suggesting that one of the earliest arms industries was sustained by knowledge and expertise handed down from generation to generation. Details of the haul are reported in the journal Nature. To manufacture the projectile tips, early humans must have collected raw rock materials, gathered wood for burning, known how to heat-treat the silcrete, prepare and trim the blades, and finally attach them to arrows and spears. The ability to master these tasks and pass them down to others draws on brain functions that are essential to the modern mind. |=|

“Scientists have unearthed similar stone bladelets at other sites in South Africa and Kenya, but none so old or as enduring as those discovered at Pinnacle Point. The technology spread to other parts of Africa and Eurasia around 20,000 years later. Kyle Brown, a co-author on the paper from the University of Cape Town said the team spotted the minute but carefully made tools among the smallest material collected in sieves used at the excavation site. |=|

“Marean believes the combination of more advanced weapons and greater cooperative behaviour among the early humans was a "knockout punch" for the Neanderthals. "Combine them, as modern humans did, and still do, and no prey or competitor is safe," he said. "This probably laid the foundation for the expansion out of Africa of modern humans and the extinction of many prey as well as our sister species such as the Neanderthals." In an accompanying article, Sally McBrearty, an anthropologist at the University of Connecticut, notes that the preparation of the stone weapon tips must have taken "days, weeks or months" and been interrupted from time to time by more urgent tasks. This suggests the early human weapons-makers had the brain power to hold tasks and future plans in their memories. |=| “The invention of stone bladelets in south Africa may have defined the success of humans as they moved north to occupy the rest of the world. In the journal, Prof McBrearty writes: "Human populations are thought to have started migrating from Africa shortly after 100,000 years ago. If they were armed with the bow and arrow, they would have been more than a match for anything or anyone they met." |=|

Neolithic Bowhunting May Have Fostered Social Cohesion

Bushman with a bow and arrow

Bowhunting during the Neolithic period may have been one of the pillars of unity as a group of primitive human societies. This is one of the main conclusions reached by a team of Spanish archaeologists that has analyzed the Neolithic bows found in the site of La Draga (Girona, Spain). The study has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science. [Source: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, February 2, 2015]

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona reported: "Comparing the scarce remains of wild animals and the abundant hunting gear found in the site, we conclude that nutrition was not the main aim of developing hunting objects. Neolithic archery could have had a significant community and social role, as well as providing social prestige to physical activity and individuals involved in it," explains the researcher Xavier Terradas, from the Milá i Fontanals Institution (IMF-CSIC). “According to the study, in some cases, prestige was linked to the type of hunted animal and, at other times, had more to do with the distribution of the prey than with the capture of the animal itself. Raquel Piqué, UAB's researcher, adds: "As a collective resource, larger preys may have played an important role, even in those cases when they constituted a punctual or sporadic resource."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024