EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING AND GATHERING

During the Ice Age between 30,000 and 15,000 years ago, Europe was covered mostly by open steppe, an ideal habitat for grazing animals like horses, rhinos, deer, mammoth, reindeer and bison. Vast herds of these animals fed on grass, nourished by glacier melt, and roamed across Europe and Asia. As the Ice Ages ended and the climate warmed up, the habitat for the large animals herds declined as the vast grasslands were invaded by birch and evergreen forests.

Analysis of over a thousand animal bones from the 45,000-year-old Ranis site in Germany showed that early Homo sapiens processed the carcasses of deer but also of carnivores, including wolf. The team that excavated the site also found more than a thousand bone fragments belonging to animals that frequented the caves, such as bears and hyaenas, as well as those that may have been a part of the humans’ diet, such as deer and horses. Researcher Geoff Smith said: “Zooarchaeological analysis shows that the Ranis cave was used intermittently by denning hyaenas, hibernating cave bears, and small groups of humans. While these humans only used the cave for short periods of time, they consumed meat from a range of animals, including reindeer, woolly rhinoceros, and horses.” [Source: Nilima Marshall, PA Media, February 1, 2024]

Many scientists believe that early modern humans were more likely hunters and gatherers than macho spear-welding hunters. Basing their conclusions on archaeological evidence and studies of modern hunters and gatherers, the scientists believe that early human women collected edible plants, seeds and roots and men more likely employed relatively safe net hunting than threw spears at mighty beasts. [Source: Discovery, April 1998]

In modern hunter-gatherer societies, most of the calories come from the women's work. Men often come home empty-handed, which means that it falls to the women to provide much of the food. The scientists that have presented this view made these conclusions based on several theories and facts: 1) Hunter gatherers rarely go after big animals like elephants. Before the 5th century B.C. there is no evidence of pre-iron-age tribal hunters in Africa or Asia making a living from killing large animals. 2) Fiber technology was around at least 7,000 years ago, and evidence of mesh have been found at 20,000 year-old European sites, suggesting that nets like those used by pygmies to catch animals could have been used that long ago. 3) Evidence of fibers and plant foods are more likely or deteriorate than large bones, explaining why there isn't much evidence of plant foods and fibers. 4) Pollen samples from European Ice Age sites contains pollen from 70 plants. These plants are almost the same as those eaten by sub-Arctic people today. 5) Large bones found in caves were just as likely to have scavenged as from hunted animals. The bones found at archaeological sites was often weathered at different rates and found near natural salt licks and water holes (were animals often die) which suggests it may have been scavenged.

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

See Separate Articles:

DIET OF OUR HUMAN ANCESTORS europe.factsanddetails.com;

STUDYING PREHISTORIC DIETS factsanddetails.com ;

FOOD OF EARLY MODERN HUMANS (100,000-10,000 YEARS AGO) factsanddetails.com;

MEAT EATING BY MODERN HUMANS 200,000 TO 10,000 YEARS AGO europe.factsanddetails.com

EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING AND MEAT PROCESSING TECHNIQUES europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL FOOD AND DIET europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL MEAT EATING AND FISH AND SEAFOOD CONSUMPTION europe.factsanddetails.com ;

NEANDERTHAL HUNTING: METHODS, PREY AND DANGERS europe.factsanddetails.com ;

LATE STONE AGE AND BRONZE AGE DIET AND FOOD factsanddetails.com;

STONE AGE BREAD AND GRAIN CONSUMPTION factsanddetails.com;

MEAT EATING BY LATE STONE AGE HUMANS factsanddetails.com

AUSTRALOPITHECUS AND EARLY HOMININ FOOD, DIET AND EATING HABITS ; factsanddetails.com ;

HOMO ERECTUS FOOD factsanddetails.com ;

HOMININS, HOMO ERECTUS AND FIRE factsanddetails.com ;

HOMININS, HOMO ERECTUS AND COOKING factsanddetails.com ;

MEAT EATING BY HOMININS 500,000 to 80,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Hunting and Fishing in the Neolithic and Eneolithic: Weapons, Techniques and Prey”

by Christoforos Arampatzis and Selena Vitezovic (2024) Amazon.com;

“Competition Between Humans and Large Carnivores: Case studies from the Late Middle and Upper Palaeolithic of the Central Balkans” (BAR International)

by Stefan Milosevic (2020) Amazon.com;

“Projectile Points, Hunting and Identity at Neolithic Çatalhöyük, Turkey”

by Lilian Dogiama (2023) Amazon.com;

“Arrowpoints, Spearheads, and Knives of Prehistoric Times” by Thomas Wilson (2022) Amazon.com

“A View to a Kill: Investigating Middle Palaeolithic Subsistence Using an Optimal Foraging Perspective” (2008) by G. L. Dusseldorp Amazon.com

“Meat-Eating and Human Evolution” by Craig B. Stanford, Henry T. Bunn Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Hominin Diets: Integrating Approaches to the Study of Palaeolithic Subsistence” by Jean-Jacques Hublin, Michael P. Richards, Editors (2009) Amazon.com;

“Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human” by Richard Wrangham Amazon.com;

“Evolution's Bite: A Story of Teeth, Diet, and Human Origins” by Peter Ungar (2017) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Cookery, Recipes and History,” by Jane Renfrew (English Heritage, 2006) Amazon.com

“Evolution of the Human Diet: The Known, the Unknown, and the Unknowable” by Peter S. Ungar Amazon.com;

The Paleo Diet Revised: by Loren Cordain Amazon.com;

“Homo Sapiens Rediscovered: The Scientific Revolution Rewriting Our Origins” by Paul Pettitt Amazon.com;

“Handbook of Paleolithic Typology: Lower and Middle Paleolithic of Europe” by Andre Debenath , André Debénath , et al. Amazon.com

“The Palaeolithic Settlement of Europe (Cambridge World Archaeology)” by Clive Gamble (1986) Amazon.com

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013)

Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

Early Modern Human Weapons

Unlike Neanderthals who attacked their prey directly and relied on thrusting spears for hunting at close quarters, modern humans hunted at a distance with spear throwers that were effective from 30 to 50 feet away. These were tipped by a variety of carefully wrought stone and bone points. The throwing spears used by modern humans made hunting more efficient and less dangerous. At the 20,000-year-old Sungir site in Russia archaeologist unearthed 11 dartlike spears, three daggers and two long spear. One of the spears was 8-feet-long and had a point fashioned from a mammoth tusk.

The earliest weapons on record are spears with stone points dating to 460,000 years and found in southern Africa. Between 400,000 and 380,000 years ago, when the early human relatives Homo heidelbergensis lived in Europe, wooden spears shaped from branches of spruce and pine trees were used in Europe. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: Recent research has shown that later hunters were able to kill their animal prey at a distance with spears: For instance, a study of the wounds on deer bones found at Neanderthal hunting sites show that the spears were thrown at their prey from several feet away, instead of being used in an attack at close quarters. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 24, 2019]

mammoth ivory atlatl (spear-thrower)At some point modern humans also invented primitive bow and arrows which are deadly from distance of around 100 feet. The bow is regarded by some as the first machine since it had moving parts and converted musculature energy to mechanical energy. Hunting weapons like spears and arrows saw big changes from the specialization of tools in the Upper Paleolithic period (50,000 to 10,000 years ago). As the shaping of bones and antlers became common, they were formed into spear points, arrowheads, harpoons and fishhooks — often highly decorated, and with intricate rows of barbs to prevent them from being shaken loose by fleeing prey. Antler spear points dated to between 19,000 and 11,000 years ago have been found in southwest France.

Twelve-thousand-year-old cave art in Altira Spain shows men with bows, perform outflanking movement. By 10,000 years ago modern humans were using maces (derived from club) and slings (derived from bolas, which wrapped around legs of animals). These tools and bows and arrows marked difference between old stone age (Paleolithic period) and new stone age (Neolithic period). [Source: History of Warfare by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

For Information on Spears See HUNTING BY HOMININS 500,000 TO 100,000 YEARS AGO europe.factsanddetails.com

Atlatls (Spear-Throwers)

Modern humans devised spear-throwers called atlatls The atlatl is a two-piece weapon consisting of a lever arm fitted on the end of a light spear. The lever helps thrust the spear with greater velocity than a hand-thrown spear. Used in Europe, the Americas and Australia, it was a common weapon before bows and arrows were widely used and is believed to have been effective enough to bring down wooly mammoths, The weapon has made a come back in recent years. There atlatl competitions and clubs. In the United States, hunters have asked to be allowed to use the weapons in during a atlatl hunting season.

Most atlatls consists of a wooden shaft with a hook or spur at the end that attaches to a dart. Extra leverage enables users to throw heavy darts several feet (1 to 3 meters) long with precision and at high velocities. Bone spurs from atlatls have been found at several Paleolithic sites, indicating that the weapon was widely used by hunters from about 20,000 years ago. "It is easier to make darts for hunting big game than to make a reliable bow with comparable power, and you can carry more darts than spears or javelins," Justin Garnett, a doctoral student in archaeology at the University of Kansas, told Live Science. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 3, 2023]

Atlatls allowed early hunters to hunt game from farther away. They may have given modern humans an advantage over Neanderthals. A number of stone points discovered at the Gault site, in central Texas, were most likely hafted onto wooden shafts and hurled with atlatls at targets such as bison and mammoths, Tom Williams of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin, told Archaeology magazine. The points have been dated to between 20,000 and 16,000 years ago, making them the oldest projectile points unearthed in the Americas. [Source: Daniel Weiss, Archaeology magazine, May-June 2020]

Are Mysterious C-Shaped Carvings Atlatl Finger Loops?

This image shows a hand clenching around the end of a wooden spear, with the forefinger in the "open ring" finger loop; Image from Justin Garnett

It turns out that enigmatic,C-shaped antler carvings from France's Stone Age that puzzled scientists for over 150 years are likely atlatl finger loops according to the study, published March 22, 2023 in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology by Justin Garnett and Sellet, at the University of Kansas. The discovery was made by using similar crescent-shaped devices to throw dart-like projectiles at archery targets. The success of these trials suggests that the objects — made of deer antler and called "open rings" — were once attached to now-rotted-away wooden atlatls that were used to throw large darts at high speeds. "The rings come from the kinds of sites where gear maintenance would have been performed, and they look like finger loops and work well as finger loops," Garnett told Live Science."That said, we should always be cautious when assigning functions to prehistoric artifacts — there's always the chance that we may be mistaken." [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, June 3, 2023]

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: The first open ring was discovered among Upper Paleolithic artifacts at Le Placard Cave in southwestern France in the 1870s. Since then, 10 more have been found, all in France, as well as one "preform" — an open ring that was in the process of being carved but still attached to the rest of the antler. Only the preform has been directly dated, showing it was made about 21,000 years ago, by early modern humans of the Magdalenian culture or the Badegoulian culture that preceded it.

Each open ring is an arc a bit more than 1 inch (3 centimeters) high and about 2 inches (5 cm) long; each of the two ends has a horizontal tab, giving it the shape of the Greek letter omega. Some archaeologists suggested that the rings may have been ornaments or fasteners for clothing. Garnett did experiments with replicas of the open rings — made from cattle bones, elk antler and 3D-printed plastic — that he attached to replica spear-throwers. These experiments suggested that open rings welled as finger loops, this matched the patterns of wear on them.

Oldest Evidence of Arrows — 72,000 and 64,000 Years Ago from South Africa

According to Archaeology magazine: An analysis of bone arrowheads from Blombos Cave indicates that this technology may date back 72,000 years. The shape and small size of the points found there suggests that they were likely coated in toxins; otherwise their diminutive nature would have rendered them virtually ineffective. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2020]

In August 2010, researchers in South Africa announced in a study in the journal Antiquity they had found the earliest evidence of human-made arrows — 64,000 year-old "stone points" that contained remnants of blood, bone and gluethat was offered they were used as arrows for hunting. The arrow heads were unearthed in Sibudu Cave in South Africa during an excavation led by Professor Lyn Wadley from the University of the Witwatersrand. The discovery pushed back the development of "bow and arrow technology" by at least 20,000 years.[Source: Victoria Gill, BBC News, August 26, 2010]

Marlize Lombard, also from the University of the Witwatersrand, which is Johannesburg led the examination of the findings. She described her study as "stone age forensics" and told the BBC: "We took the [points] directly from the site, in little [plastic] baggies, to the lab. "Then I started the tedious work of analysing them [under the microscope], looking at the distribution patterns of blood and bone residues." The BBC reported: Because of the shape of these "little geometric pieces", Dr Lombard was able to see exactly where they had been impacted and damaged. This showed that they were very likely to have been the tips of projectiles — rather than sharp points on the end of hand-held spears.

The arrow heads also contained traces of glue — plant-based resin that the scientists think was used to fasten them on to a wooden shaft. "The presence of glue implies that people were able to produce composite tools — tools where different elements produced from different materials are glued together to make a single artefact," said Dr Lombard. "This is an indicator of a cognitively demanding behaviour."

Researchers are interested in early evidence of bows and arrows, as this type of weapons engineering shows the cognitive abilities of humans living at that time. They wrote in their paper: "Hunting with a bow and arrow requires intricate multi-staged planning, material collection and tool preparation and implies a range of innovative social and communication skills." Dr Lombard explained that her ultimate aim was to answer the "big question": When did we start to think in the same way that we do now? "We can now start being more and more confident that 60-70,000 years ago, in Southern Africa, people were behaving, on a cognitive level, very similarly to us," she told BBC News.

Professor Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London said the work added to the view that modern humans in Africa 60,000 years ago had begun to hunt in a "new way". Neanderthals and other early humans, he explained, were likely to have been "ambush predators", who needed to get close to their prey in order to dispatch them. Professor Stringer said: "This work further extends the advanced behaviours inferred for early modern people in Africa." "But the long gaps in the subsequent record of bows and arrows may mean that regular use of these weapons did not come until much later. "Indeed, the concept of bows and arrows may even have had to be reinvented many millennia [later]."

Currently, the earliest evidence of bow hunting technology outside Africa comes from southern Europe, and dates to around 54,000 years ago (See Below).

Also See First Use of Poison Arrows — 72,000 Years Ago in South Africa? Under EARLY MODERN HUMAN HUNTING AND MEAT PROCESSING TECHNIQUES europe.factsanddetails.com

Bow and Arrow Technology — an Indicator of Cognitive Ability?

The four scientists listed below wrote in The Conversation Bow and arrow technology gives hunters a unique advantage over their prey. It allows them to hunt from a distance, and from a concealed position. This, in turn, increases individual hunters’ success, as well as providing an aspect of safety when stalking dangerous prey such as buffalo, bushpig, or carnivores. [Source: 1) Justin Bradfield, University of Johannesburg; 2) Jerome ReynardUniversity of the Witwatersrand; 3) Marlize Lombard Palaeo-Research Institute, University of Johannesburg; 4) Sarah Wurz Professor, University of the Witwatersrand, May 17, 2020]

The bow and arrow consists of multiple parts, each with a particular function and operating together to make hunting possible. This kind of “symbiotic” technology requires a high degree of cognitive flexibility: the mental ability to switch between thinking about different concepts, and to think about multiple concepts simultaneously.

From at least 100 000 years ago people in southern Africa were combining multiple ingredients to form coloured pastes, possibly for decoration or skin protection. By 70 000 years ago they were making glues and other compound adhesives using a range of ingredients, combined in a series of complex steps. These glues may have then been used, among other things, to haft small stone pieces in varying arrangements, probably as insets for arrows or other weapons.

The presence of these technical elements in the southern African Middle Stone Age (roughly equivalent to the Eurasian Middle Palaeolithic) signals an advanced cognitive ability. That includes notions of abstract thought, analogical reasoning, multitasking and cognitive fluidity or the ability to ‘think outside the box’.

60,000-Year-Old Bone Arrowheads from South Africa

Bone arrowheads were used in southern Africa at least as early as 60,000 years ago, 20,000 years before they were used in any other part of the world. Because bows and arrows were made predominantly from organic materials, very little evidence of these weapons survives archaeologically. Evidence for bow hunting technology using bone and dating back more than 60 000 years has been reported from South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal region and Eastern Cape province. The earliest non-African evidence of bone points used as arrow tips is at 35 000 years ago from Timor Island.[Source: 1) Justin Bradfield, University of Johannesburg; 2) Jerome ReynardUniversity of the Witwatersrand; 3) Marlize Lombard Palaeo-Research Institute, University of Johannesburg; 4) Sarah Wurz Professor, University of the Witwatersrand, May 17, 2020]

The four scientists listed above wrote in The Conversation: Our study, published in Quaternary Science Reviews, focused on a long, thin, delicately made, pointed bone artefact. It was found at the Klasies River Main site, along the Eastern Cape coast of South Africa. This is an extremely important archaeological site. It has the most prolific assemblage of H. sapiens remains in sub-Saharan Africa, spanning the last 120,000 years. The artefact we studied, which comes from deposits dated to more than 60,000 years ago, closely resembles thousands of bone arrowheads used by the indigenous San hunter-gatherers from the 18th to the 20th centuries.

Our study followed a combined approach, incorporating microscopic analysis of the bone surface, high-resolution computed tomography (CT), and non-destructive chemical analysis. The study found trace amounts of a black, organic residue distributed over the surface of the bone point in a manner suggestive of 20th century poisoned arrows. The chemistry of the black substance indicates it consists of many ingredients. Again, this is suggestive of known San poison and glue recipes. Microscopic analysis of the bone artefact indicates that it was hafted (or attached) to another arrow section – probably into a reed shaft. This was done after the black residue was applied. The micro-CT scan allowed us to look inside the bone, to see structural damage at a microscopic scale. These results showed that the bone artefact had experienced the same mechanical stresses as high-velocity projectiles, like arrows.

The study demonstrates that the pointed bone artefact from Klasies River was certainly hafted, maybe dipped in poison, and used in a manner similar to identical bone points from more recent contexts. The artefact also fits in with what we know of ancient people’s cognition and abilities in southern Africa.

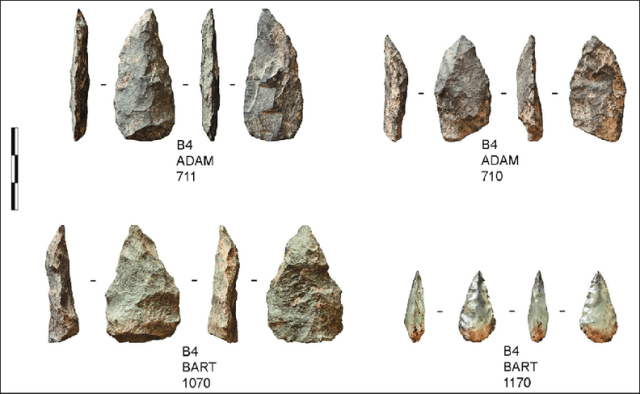

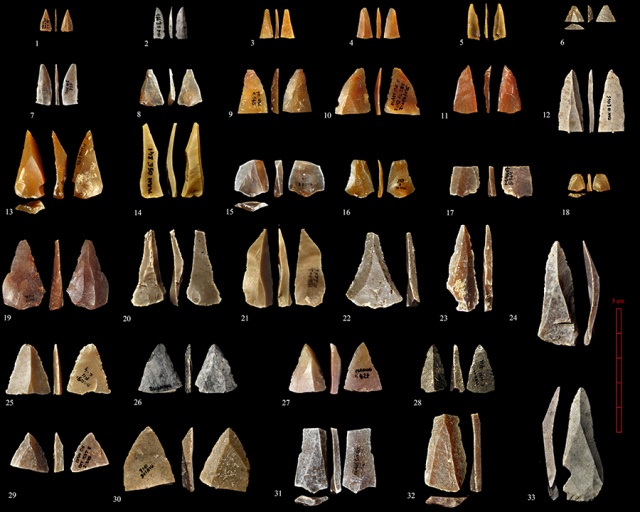

Oldest Arrows in Europe — 54,000-Year-Old Stone Points from France

In February 2023, scientists published a study in the journal Science Advances, saying that they had found evidence of bows and arrows being used by early modern humans in Europe 54,000 years ago. The study describes dozens of stone points, some of them very small, found in the Grotte Mandrin rock shelter in the Rhône River valley in southern France. The points varied vary in size and researchers think the largest were used on spears and smaller ones were used as arrowheads. Among other things the discovery supports the idea that projectile technology such as bows and arrows might have given early modern humans an edge over Neanderthals and helped them spread through Europe.

Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science, Researchers found the telltale stone points in a rock shelter that was inhabited by early modern humans about 54,000 years ago. Until now, 12,000-year-old wooden artifacts in Northern Europe were the earliest concrete evidence of bow-and-arrow technology on the continent. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, March 2, 2023]

In a study published in the journal Science Advances in 2022, many of the same researchers reported finding teeth and stone artifacts that showed early modern humans occupied the site between 56,700 and 51,700 years ago — pushing back the earliest known date of the arrival of early modern humans in Europe by about 10,000 years. The new study examined hundreds of stone artifacts from the same site and around the same age, many of which showed telltale signs of use as projectile weaponry, including more than 100 points that appear to be parts of arrowheads. Many were similar to arrowheads made by later Homo sapiens, and some had fractures and other damage at their tips that could have been created by an impact.

Study author Laure Metz, an archaeologist and anthropologist from Aix-Marseille Universite in France and the University of Connecticut, and his team also made replica points from stone found near the rock shelter and fashioned them into arrows, darts for atlatls (spear-throwers), and spears, which they then used to shoot at or stab dead goats to simulate hunting prey. They found that some of the larger points could have been effective with spears but that the smallest points wouldn't have been damaging enough without the force from a bow and arrow.

48,000-Year-Old Evidence of Bow-and-Arrow Found in Sri Lanka

In a paper published in June 2020 in Science Advances, scientists announced that they had had discovered the what at the time was believed to be the earliest evidence of a bow-and-arrow outside of Africa — a 48,000-year-old bow- and-arrow kit found at the Fa-Hien Lena cave in southwestern Sri Lanka — along with other advanced hunting tools and weapons carved from animal bones and teeth. [Source:Daisy Hernandez, Popular Mechanics, June 17, 2020]

“According to the paper, Sri Lanka has become “a particularly important region for understanding how our species managed to successfully colonize a wide variety of environments among a backdrop of changing climates.” The researchers, who called their discovery a “diverse toolkit,” add that the items they found may also represent “some of the earliest clothing or nets in a tropical setting.” After analyzing faunal remains, the researchers concluded that the tools made of bone were created on site at Fa-Hien Lena.

Daisy Hernandez wrote in Popular Mechanics: “They also found unfinished tools and byproduct left behind from forged weapons that indicated the site saw a lot of activity. In fact, the paper describes “four distinct phases of occupation” spanning the late Pleistocene to the early and middle Holocene periods. The paper additionally cites a short period “outside these phases,” which could represent “a short-lived episode of human presence within the cave.” The detail-rich site features artifacts with cut marks on them “consistent with those produced during retooling activities,” which the researchers say indicated tool and weapon maintenance.

“The researchers hope that more attention is given to sites “beyond the traditional heartlands of paleoanthropological and Paleolithic archaeological research” so that we can better understand the technological advancements that were made when early man roamed the Earth.

Did Archery Help Modern Humans Gain an Advantage over Neanderthals

The discovery of the use of bow and arrows by modern humans 54,000 years ago France, not so long before modern humans began to take over territory occupied b Neanderthals, suggests the weapons gave humans an advantage over Neanderthals. Tom Metcalfe wrote in Live Science: there is no evidence that Neanderthals ever used bows and arrows (although they seem to have been adept at throwing spears). And that could be one of the reasons early modern humans ultimately supplanted the Neanderthals across Europe about 40,000 years ago, according to research led by scientists in France, including Laure Metz, an archaeologist at Aix-Marseille University, and Ludovic Slimak, a cultural anthropologist at the University of Toulouse-Jean. "These technologies may have given modern humans a competitive advantage over local Neanderthal societies," the researchers wrote. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, March 2, 2023]

The evidence from Grotte Mandrin indicates that early modern humans were proficient with bows and arrows at the very earliest stage of their incursion into Europe, contrary to the proposal by some archaeologists that they mastered this technology only after they had supplanted the Neanderthals. For instance, some archaeologists have argued that the small points found at the earliest South African sites were created during the process of making spears and may not be evidence of early arrows.

The rock shelter at Grotte Mandrin was occupied by several different groups at different times. The earliest phase of Neanderthal occupation was about 120,000 years ago. The new study suggests that the use of bows, arrows and atlatls might have been a critical advantage for modern humans as they expanded across Europe and eventually replaced the Neanderthals. "The use of these advanced technologies may be of crucial importance in the understanding of the remarkable expansion of the modern populations," they wrote. According to a report in Nature magazine, Grotte Mandrin also contains the bones of horses, and the researchers think early modern humans may have hunted these and bison migrating through the Rhône River valley.

“Bows are used in all environments, open or closed, and are effective for all prey sizes,” Metz told Popular Science. “Arrows can be shot quickly, with more precision, and many arrows can be carried in a quiver during a hunting foray. These technologies then allowed an uncomparable efficiency in all hunting activities when Neanderthals had to hunt in close or direct contact with their prey, a process that may have been much more complex, more hazardous and even much more dangerous when hunting large game like bison.” [Source: Laura Baisas, Popular Science, February 22, 2023]

Mastodons Not Hunted to Extinction by Humans: They Froze to Death, Study Says

mastadon

It has long been held that mastodons were wiped out by spear-carrying human hunters but a Canadian-led study published in 2014 said they more likely froze to death. “To think of scattered populations of Ice Age people with primitive technology driving huge animals to extinction, to me is almost silly,” said Grant Zazula, chief paleontologist for the Yukon Territory and the study’s lead author. “It’s not human nature just to see everything in your path and want to kill it.” [Source: Tristin Hopper, Associated Press, December 1, 2014 /=]

Tristin Hopper of Associated Press wrote: “The paper, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, carbon dated 36 mastodon bones from across Canada and the United States. What the research found was that mastodons died out in the Yukon and Alaska long before humans were even on the scene. Not only that, but northern mastodons died out a full 65,000 years before their cousins in warmer climes to the south. /=\

“For decades, paleontology has held that many North American Ice Age giants, from mammoths to giant sloths to mastodons, were wiped out by the spears of “Paleo-Indians” migrating into North America soon after crossing the Bering land bridge. The rather unexciting implication of the study is that mastodons were most likely done in by shifting environmental conditions — rather than by a killing frenzy by the predecessors of modern-day First Nations. “You can’t just hold up a flag and say it was one thing that led to the extinction of all these species,” said Mr. Zazula. “It wasn’t like they all collapsed in one instant across the continent.” /=\

“Mastodons, furry elephantine creatures that once ranged from Florida to Alaska, disappeared from the North American continent about 10,500 years ago. Their time in what is now the Canadian North appears to have been brief, and occurred during a short-lived interglacial period when temperature and conditions would have been similar to today. “They migrated northward: ‘Let’s come up to Alaska and the Yukon on a vacation to see what it’s like,’ but then when conditions got cold again they were immediately wiped out,” said Mr. Zazula. /=\

“Although the study is hesitant to say it definitively, the Yukon die-off could well have been a preview of coming attractions for North America’s beleaguered mastodons. As colder temperatures crept south, southerly mastodon herds joined their Northern Canadian brethren in being pushed off the map. Ross MacPhee, a researcher at the American Museum of Natural History and a co-author of the Yukon study, said in a statement that human may well have dealt the death blow to mastodons, but only after they had shrunk to a small population clinging to life around what is now the Great Lakes. “That’s a very different scenario from saying the human depredations caused universal loss of mastodons across their entire range within the space of a few hundred years, which is the conventional view,” he said. /=\

“Fringe theories, meanwhile, hold that, just like the dinosaurs, North America’s megafauna was simply struck down in their prime by a wayward asteroid — or by cross-continental disease pandemics. In 2006, for instance, a study published in a German scientific journal claimed to have found evidence of a devastating tuberculosis outbreak among mastodons./=\

“Due to their brief northern residency, mastodon bones are rare in the fossil-rich Yukon. Much of the territory was unaffected by the glaciers of the last Ice Age, leaving its frozen soil packed with the bones, skin and even footprints of long-extinct prehistoric creatures. Mammoths, by contrast to snow-shy mastodons, were much more successful at eking out a living in the frozen North — and held on until 10,000 years ago. As a result, hardly a week goes by during the summer months when mammoth parts aren’t turning up in Yukon gold mines.” /=\

How Humans Changed the Siberian Ecosystem

big fauna consumed at Blombos Cave in South Africa

According to AP: "Northeastern Siberia, today one of the coldest and most formidable spots on the globe, was dry and free of glaciers. The ground grew thick with fine layers of dust and decaying plant life, generating rich pastures during the brief summers. When humans arrived they hunted not only for food, but for the fat that kept the northern animals insulated against the subzero cold, which the hunters burned for fuel, say the scientists. They may also have killed for prestige or for sport, in the same way buffalo were heedlessly felled in the American Old West, sometimes from the window of passing trains. [Source: AP, November 29, 2010 ^^^]

"The wholesale slaughter allowed the summer fodder to dry up and destroy the winter supply, they say. "We don't look at animals just as animals. We look at them as a system, with vegetation and the whole ecosystem," said the younger Zimov. "You don't need to kill all the animals to kill an ecosystem." During the transition from the Ice Age to the modern climate, global temperatures rose 5 degrees Celsius, or 9 Fahrenheit. But in Siberia's northeast the temperature soared 7 degrees, or nearly 13F, in just three years, the elder Zimov said. ^^^

"The theory of human overkill is much disputed. Advocates of climate theory say the warm wet weather that accompanied the rapid melting of glaciers spawned birch forests that overwhelmed the habitats of the bulky grass eaters. Adrian Lister, of the paleontology department of London's Natural History Museum, said humans may have delivered the final blow, but rapid global warming was primarily responsible for the mammoth's extinction. It brought an abrupt change in vegetation that squeezed a dwindling number of mammoths into isolated pockets, where hunters could pick off the last herds, he said. ^^^

People "couldn't have done the whole job," he told the Associated Press Television News. Mammoths once ranged from Russia and northern China to Europe and most of North America, but their numbers began to shrink about 30,000 years ago. By the time the Pleistocene era ended they remained only in northern Siberia, Lister said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024