HOMININS, APES AND MONKEYS

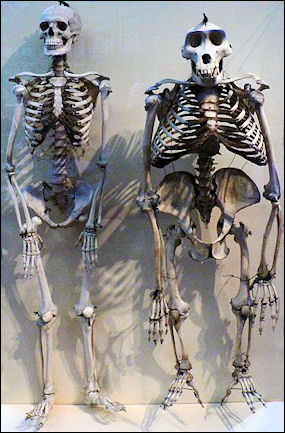

human an gorilla skeletons Hominins are defined as creatures that stand upright and walk and run primarily on two legs, while apes are creatures that hunch over and, although capable of walking on two legs, prefer to use their arms when moving on the ground. Before the mid 2000s, scientists often referred to hominins as hominids. Hominids are all modern and extinct great apes: gorillas, chimps, orangutans and humans, and their immediate ancestors. Not gibbons. Hominins are any species of early human that is more closely related to humans than chimpanzees, including modern humans themselves.

What distinguishes an ape from a monkey is the fact that apes don’t have a tail. Humans are apes. They are just as hairy as other apes, but their hair is shorter and finer. Apes are regarded as more intelligent than monkeys. They have rapid eye movement and may dream. They can recognize themselves in a mirror while monkeys think they are confronted with another monkey. Apes and humans are the only creatures that have spindle cells — large cigar-shaped cells neurons linked with emotion, problem-solving, a moral sense and a feeling of free will — in their brains.

Research by geneticists in the mid 2000s determined that the human genome and chimpanzees are only different by 1.23 percent. The one small percentage difference encompasses 35 million individual chemical changes accumulated over the 5 million to 7 million years during which the species evolved apart. Put another way humans and chimpanzees share 98.77 percent of the same genetic material. Not everyone likes this figure. A study in Japan however that 15 percent of genes of humans and chimpanzees are different.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor” by Colin Tudge with Josh Young Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

Timeline of Monkey, Ape and Hominin Development

Scientists have found fossils of 5,000 individual hominins as far back as 4.4 million years, perhaps 7 million years. The earliest hominins, the genus Australopethecus, possessed long arms, short legs, a large small brain and a large face. These creatures would appear to us today as more ape-like than human-like. So far the earliest hominins species have been discovered only in eastern, northern and south Africa. Scientists describe Africa as the "cradle of mankind" because all of the oldest hominin remains have been found there.

About 25 million years ago the line that would eventually lead to apes split from the old world monkeys. Between 20 million and 14 million years ago orangutans split off from the other “great apes,” chimpanzees, gorillas and humans. Between 14 million and 5 million years ago numerous species of early apes spread across Asia, Europe and Africa

Archicebus achilles

✦395 million years ago: Tetrapods evolve from lobe-finned fish, as animals move on to the land.

✦ 55 million years ago: Archicebus achilles living in what is now China.

✦ 47 million years ago: Darwinius masillae living in Messel pit area of what is now modern Germany.

✦Between 8 million and 4 million years ago: First the gorillas, and then chimpanzees and bonobos split off from the evolutionary lineage that led to humans.

✦ 3.8 million years ago: Australopithecus afarensis, an ape-like hominin living in Africa. Most famous fossil is Lucy.

✦ 300,000 years ago: Homo sapiens evolves in Africa.

✦Between 125,000 and 60,000 years ago: Homo sapiens leaves Africa. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, June 5, 2013]

Early attempts to plot the course of human evolution tried to present nice neat linear models with one species leading directly to another. The more discoveries that were made the less the neat models became. Modern models of human evolution look like groups of trees with lots of entangled branches — some that lead to dead ends and others that continue on and interconnect to other branches. In the old days many thought who studied early man were regarded as “lumpers” because they tended to lump discoveries into group. In recent years they have taken a backseat too “splitters,” who shy away from grouping new discoveries and instead often define them as new, separate species.

New discoveries have also debunked theories that human evolution was marked by a series of nice, neat progressions and advancements. Sometimes new discoveries dated to a certain period seem more primitive than older finds. Some features in one species appear and then disappear and then re-emerged in later species, making the features insignificant as some sort of milestone. Bernard Wood of George Washington University told Newsweek, “Similar traits evolved more than once, which means you can’t use them as gold-plated evidence that one fossil is descended from another or that having an advanced trait means a fossil was a direct ancestor of modern humans.”

Earliest Known Primate: A Tiny, Insect-Eating Creature from China

The oldest primate fossils date to around 55 million years ago. There is circumstantial evidence based on mathematics and probability that they lived as far back as 80 million years which would have made them contemporaries of the dinosaurs.

Archicebus achilles, a tiny-insect-eating creature that lived 55 million years ago present-day China, is regarded as the ancestor of all monkeys, apes and humans Alok Jha wrote in The Guardian: “A tiny animal with slender limbs, a long tail and weighing in at no more than 30 grams, has become the earliest known primate in the fossil record. Archicebus achilles lived on a humid, tropical lake shore 55 million years ago in what is now China and is the ancestor of all modern tarsiers, monkeys, apes and humans. Scientists found the fossil, whose name translates as "ancient monkey", in the Hubei province of China about a decade ago but it hasn't received detailed analysis until now. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, June 5, 2013 |=|]

“About seven centimeters long, Archicebus lived in the trees and its small, pointed teeth are evidence that its diet consisted of insects. The fossil's large eye sockets indicate a creature with good vision and, according to scientists, it probably hunted during daytime. Xijun Ni of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who led the study of the fossil, described the animal as having a very long tail, slender limbs, a round face and feet capable of grasping. "Maybe it would also have had colours and it would have preyed on insects," he said. A full description of the fossil is published in the latest edition of Nature. |=|

“The analysis shows that the fossil had a mixture of features found in modern-day tarsiers, an ancient group of primates that is now restricted to the islands of South East Asia, and others found in anthropoids, the lineage through which monkeys, apes and humans later evolved. Whereas Archicebus's foot looks like that of a modern-day marmoset, for example, the heel bone looks more like those seen in the earliest fossil anthropoids. |=|

“Chris Beard of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, a co-author on the Nature paper, added that, because the animal was so small and "active metabolically, it was probably quite a frenetic animal, you could even think anxious. Very agile in the trees, climbing and leaping around in the canopy. The world it inhabited along that lake shore in central China was amazing – hot, humid, very tropical." |=| “Archicebus was alive during a period of intense global warming known as the palaeocene-eocene thermal maximum, a time when palm trees would have been growing as far north as Alaska. Dr Christophe Soligo, a biological anthropologist at University College London, said the discovery of the fossil was a significant contribution to scientific knowledge of early primate evolution. "It does not only contribute new fossil material to a period for which very little is preserved, but it contributes a new specimen that is astonishingly complete for its age." |=|

“To study the delicate skeleton without damaging it, scientists created a high-resolution, digital reconstruction of the fossil using x-rays at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility in Grenoble, France. Dr Jerry Hooker, a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, said: "Most mammal fossils, including those of primates, are fragmentary, usually consisting of isolated teeth or jaws, sometimes also other skeletal elements, and we have learned a lot from these. However, to have a 50 percent complete articulated skeleton of a primitive primate is much more instructive in terms of estimating lifestyle and relationships."” |=|

Ida: the 47-Million-Year-old “Missing Link”

In a review of the book: “The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor” by Colin Tudge with Josh Young, Guy Gugliotta wrote in the Washington Post: “In 2006, paleontologist Jorn Hurum, of the University of Oslo's Natural History Museum, was shown the remains of a small, (22 inches) juvenile female primate from the oil shales of the Messel Pit, near Frankfurt, Germany, one of Europe's most famous fossil beds. The fossil had been discovered in 1983 by a private collector who wanted to sell it. His asking price was $1 million. Hurum was immediately smitten, for the find "represented a once-in-a-lifetime experience for any paleontologist." The museum bought it. [Source: Guy Gugliotta, Washington Post, June 28, 2009 ||=||]

“Hurum assembled a team of experts to analyze and describe the fossil, a process that has thus far taken three years. The team concluded that "Ida," so named in honor of Hurum's daughter, shared characteristics with evolutionary lineages that led both to modern lemurs and to the anthropoids — including humans. "In other words," Tudge writes, "Ida appears to be an in-between species, or one of the long-sought missing links in evolution." ||=||

“In their peer-reviewed paperin the online scientific journal PLoS One, Hurum and his team say Ida "could represent a stem group from which later anthropoid primates evolved, but we are not advocating this here." Tudge describes Ida's world, a tropical forest with a volcanic lake that one day belched a gigantic bubble of toxic gas that asphyxiated this small creature and plunged it into the mud for all eternity. ||=||

"The Link" isn't just about a monkey fossil. It's about paleontology and paleontologists, warts and all. As noted, Hurum bought his fossil at an annual fair in Hamburg, Germany, from a collector, and paid big bucks for it. Many scientists regard such transactions as mortal sin, for they can encourage looting and the destruction of fossil sites, damaging ancient contexts that can never be reconstructed. In Tudge's telling, Hurum carefully selects his research team, knowing that it must be not only expert but also beyond professional reproach, because colleagues will relentlessly scrutinize its work. He needs a primate specialist. He needs a tooth expert. He needs somebody who knows the Messel Pit.” ||=||

Books: “The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor” by Colin Tudge with Josh Young (Little, Brown, 2009); “Origins: The Story of the Emergence of Humans and Humanity in Africa” edited by Geoffrey Blundell (Double Storey, 2006)

Development of Early Primates, Lemurs and Monkeys

Alok Jha wrote in The Guardian: ““The Archicebus skeleton is about 7 million years older than the oldest currently known fossil primate skeletons, including Darwinius massilae from Messel in Germany, an extremely well-preserved fossil was that reported by scientists in 2009. Better known as Ida, it was originally thought to be a direct ancestor of the primate lineage leading to monkeys, apes and humans – but further analysis suggests Ida is closer to early lemurs. [Source: Alok Jha, The Guardian, June 5, 2013 |=|]

“The discovery of Archicebus in China lends weight to the idea that the first and most pivotal steps in primate evolution, including the beginnings of anthropoid evolution, almost certainly took place in Asia, rather than Africa. "The evidence that early primate revolution was restricted to Asia is becoming more compelling by the day," said Beard. "It consists of two different types of data – the first is genomic. If we sequence the DNA of living primates and other mammals, we find out that the closest living relatives of primates are animals like tree shrews and flying lemurs and these are animals that only live today in Asia, specifically south-eastern Asia." |=|

“The second strand of evidence comes from the fossil record. There is some evidence of primates living in Africa about 55 million years ago, but the knowledge is patchy and comes only from a few bones and teeth. "Africa at this point in time was an island continent with a very endemic and specialised mammal fauna that in some ways resembles the modern mammal fauna of Australia in the sense that it's strange – it's not like what we see on other continents," said Beard. |=|

“At some point, the descendants of Archicebus split into the lineages that would later evolve into tarsiers and anthropoids. The latter would then have made their journey to Africa and, millions of years later, evolved into humans. "We do know that early anthropoids and early fossil relatives were somehow able to make it to Africa by the end of the Eocene, roughly 38 million years ago is our best estimate," said Beard. "We still don't know how these Asian anthropoids, which had been evolving in Asia for around 20 million years by this time, made it to Africa. But we know it could not have been easy." |=|

“At the time, Africa was an island and had yet to collide with the south western side of the continent of Asia. The early primates somehow had to cross open water in order to colonise Africa. "It couldn't have been easy but they did and, after that, obviously the story changed and Africa became a pivotal centre for anthropoid evolution," said Beard.

Early Ape-Like Primates

One of the earliest primates so far discovered is a 33 million year old arboreal animal nicknamed the "dawn ape" found in the Egypt's Faiyum Depression. This fruit-eating creature weighed about eight pounds (three kilograms) and had a lemur-like nose, monkey-like limbs and the same number of teeth (32) as apes and modern man.

Fossils of 20.6 million-year-old common ancestor of man and apes was unearthed in Uganda in the 1960s. The animals was about 1.2 meters tall and weighed between 40 and 50 kilograms and was described by thought as a "cautious climber."

In 2011, Reuters reported: Ugandan and French scientists had discovered a fossil of a skull of a tree-climbing ape from about 20 million years ago in Uganda's Karamoja region. The scientists discovered the remains in July while looking for fossils in the remnants of an extinct volcano in Karamoja, a semi-arid region in Uganda's northeastern corner. "This is the first time that the complete skull of an ape of this age has been found. It is a highly important fossil," Martin Pickford, a paleontologist from the College de France in Paris, said. [Source: Elias Biryabarema, Reuters, August 2, 2011]

Pickford said preliminary studies of the fossil showed that the tree-climbing herbivore, roughly 10-years-old when it died, had a head the size of a chimpanzee's but a brain the size of a baboon's, a bigger ape. Bridgette Senut, a professor at the Musee National d'Histoire Naturelle, said that the remains would be taken to Paris to be x-rayed and documented before being returned to Uganda. Uganda's junior minister for tourism, wildlife and heritage said the skull was a remote cousin of the Homininea Fossil Ape.

See Gigantopithecus Under PRIMATES — MONKEYS, MACAQUES, GIBBONS, AND LORISES—IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Human Ancestors Hunted by Raptors and Wolf-Size Creodonts

creodant

Early humans may have evolved as prey to animals such a s large birds and carnivorous mammals, rather than as predators, remains of primates that lived before our human ancestors suggest. Jennifer Viegas wrote in discoverynews: “The discovery of multiple de-fleshed, chomped and gnawed bones from the extinct primates, which lived 16 to 20 million years ago on Rusinga Island, Kenya, was announced today at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology’s 70th Anniversary Meeting in Pittsburgh. [Source: by Jennifer Viegas, discoverynews, October 12, 2010 ^||^]

“At least one of the devoured primates, an early ape called Proconsul, is thought to have been an ancestor to both modern humans and chimpanzees. It, and other primates on the island, were also apparently good eats for numerous predators. “I have observed multiple tooth pits and probable beak marks on these fossil primates, which are direct evidence for creodonts and raptors consuming these primates,” researcher Kirsten Jenkins told Discovery News. ^||^

“Creodonts were ancient carnivorous mammals that filled a niche similar to that of modern carnivores, but are unrelated to today’s meat eaters, she explained. The Rusinga Island creodonts that fed on our primate ancestors were likely wolf-sized. “There is one site on Rusinga Island with multiple Proconsul individuals all together and these are covered in tooth pits,” added Jenkins, a University of Minnesota anthropologist. “This kind of site was likely a creodont den or location where prey could be easily acquired.” ^||^

“Analysis of tooth pits, de-fleshing marks, bone breakage patterns, gnawing and other damage to the primate bones indicate that raptors were also hunting down these distant relatives of humans. “Primatologists have observed large raptors taking monkeys from trees,” Jenkins said. “When a raptor approaches a group of monkeys, those monkeys will make alarm calls to warn their group and attempt to retreat to lower branches. The primates on Rusinga had monkey-like postcrania and likely had very similar locomotor behavior.” Jenkins is not certain what selective pressures predators placed on these very early primate ancestors to humans, but she said they “can affect behavior, group structure, body size and ontogeny (the life cycle of a single organism).”^||^

“Robert Sussman, professor of physical anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis, has long argued that primates, including early humans, evolved not as hunters but as prey of many predators, including wild dogs and cats, hyenas, eagles and crocodiles. “Despite popular theories posed in research papers and popular literature, early man was not an aggressive killer,” said Sussman, author of the book “Man the Hunted: Primates, Predators and Human Evolution.” “Our intelligence, cooperation and many other features we have as modern humans developed from our attempts to out-smart the predator. He added that the idea of man as hunter “developed from a basic Judeo-Christian ideology of man being inherently evil, aggressive and a natural killer.” “In fact, when you really examine the fossil and living non-human primate evidence, that is just not the case,” he explained. ^||^

Did Ancestors of Humans and Apes Originate in Europe, Not in Africa?

In 2023,Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: An ape fossil found in Turkey may controversially suggest that the ancestors of African apes and humans first evolved in Europe before migrating to Africa, a research team says in a new study. The proposal breaks with the conventional view that hominines — the group that includes humans, the African apes (chimps, bonobos and gorillas) and their fossil ancestors — originated exclusively in Africa. However, the discovery of several hominine fossils in Europe and Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) has already led some researchers to argue that hominines first evolved in Europe. This view suggests that hominines later dispersed into Africa between 7 million and 9 million years ago. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, August 31, 2023]

Study co-senior author David Begun, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Toronto, clarified that they are talking about the common ancestor of hominines, and not about the human lineage after it diverged from the ancestors of chimpanzees and bonobos, our closest living relatives. "Since that divergence, most of human evolutionary history has occurred in Africa," Begun told Live Science. "It is also most likely that the chimpanzee and human lineages diverged from each other in Africa." The scientists detailed their findings Aug. 23, 2023 in the journal Communications Biology.

In the new study, the researchers analyzed a newly identified ape fossil from the 8.7 million-year-old site of Çorakyerler in central Anatolia. They dubbed the species Anadoluvius turkae. "Anadolu" is the modern Turkish word for Anatolia, and "turk" refers to Turkey. The fossil suggests that A. turkae likely weighed about 110 to 130 pounds (50 to 60 kilograms), or about the weight of a large male chimpanzee.

Based on the fossils of other animals found alongside it — such as giraffes, warthogs, rhinos, antelope, zebras, elephants, porcupines and hyenas — as well as other geological evidence, the researchers suggest that the newfound ape lived in a dry forest, more like where the early humans in Africa may have dwelled, rather than in the forest settings of modern great apes. A. turkae's powerful jaws and large, thickly enameled teeth suggest that it may have dined on hard or tough foods such as roots, so A. turkae likely spent a great deal of time on the ground.

In the new study, the scientists focused on a well-preserved partial skull uncovered at the site in 2015. This fossil includes most of the facial structure and the front part of the braincase, the area where the brain sat — features that helped the team calculate evolutionary relationships. "I was able to reconstruct and see for the first time the face of an ancestor of ours no one had ever seen before," Begun said.

The researchers suggest that A. turkae and other fossil apes from nearby areas, such as Ouranopithecus in Greece and Turkey and Graecopithecus in Bulgaria, formed a group of early hominines. This may, in turn, suggest that the earliest hominines arose in Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. Specifically, the team contends that ancient Balkan and Anatolian apes evolved from ancestors in Western and Central Europe. One question these findings raise is why, if hominines arose in Europe, they are no longer there, except for recently arrived humans, and why ancient hominines did not also disperse into Asia, Begun said. "Evolution is not very predictable," Begun said. "It happens as a series of unrelated and random events interact. We can assume that the conditions were not right for apes to move into Asia from the eastern Mediterranean in the late Miocene, but they were right for a dispersal into Africa." As for why "we do not find African apes in Europe today, species go extinct all the time," Begun said.

Caveats and Criticism of the Claim Human and Ape Ancestors Originated in Europe

In 2023,Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science:Begun also cautioned that he did not want this research misinterpreted or misused to suggest that Eurasia was somehow of primary importance in human evolution. Instead, "we need to know where the common ancestor of African apes and humans evolved so that we can begin to understand the circumstances of this evolution," he said. "Between 14 million and 7 million years ago, the areas in which apes were found in Europe, Asia and Africa were different ecologically, just as many regions in these continents differ today. Knowing the ecological conditions in which our ancestors evolved is critical to understanding our origins." [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, August 31, 2023]

This new discovery "expands our understanding of a group that appears closely related to living African apes and humans," Christopher Gilbert, a paleoanthropologist at Hunter College of City University of New York who did not participate in this study, told Live Science. However, Gilbert noted that recent comprehensive analyses of fossil great apes and early hominins — the group that includes humans and the extinct species more closely related to humans than any other animal — do not support the argument that hominines originated in Europe."Many other experts investigating the evolutionary relationships of fossil and living great apes using more modern methods and including more [groups] find that many of the European apes branched off before orangutans, making them likely distant relatives of living African great apes and humans," Gilbert said. "Furthermore, these more comprehensive analyses suggest that apes like Anadoluvius are just as likely or more likely to be recent immigrants to the Mediterranean from Africa rather than migrating back into Africa," Gilbert added.

Fossil hominines like A. turkae aren't found in Africa largely because "we have a poor African fossil record in general during this time," Gilbert said. "I am reminded of the old paleontological axiom — 'absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.'" However, Begun argued that an absence of hominine fossils in Africa was telling and supported the idea that hominines originated elsewhere.

Image Sources: Wikimedia commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024