STONE TOOLS

1.7 million years old tools from Ethiopia Toolmaking, which occurred about 3.4 million years ago, is regarded as the second major step in the development of our human ancestors. Bipedalism (moving on two legs) is regarded as first major step. It occurred between three million and seven million years ago. Some animals use and carry tools (See Below), but the act of making — deliberately fashioning — them is thought to be uniquely human.

Stone toolmaking is defined as the deliberate fashioning of a stone into a tool to perform specific tasks as opposed to simply picking up a handy rock and throwing it or bashing something with it. Toolmaking requires some skill. Flaking obsidian, for example, is very difficult. Samir S. Patel wrote in Archaeology magazine: “There are fancy obsidian blades from Mesoamerica and deftly knapped Clovis points, but many stone tools look, to the uninitiated, like … well … rocks. This is especially true of some of the simplest, oldest human-made artifacts. But there are reasons that a paleoanthropologist can pick up a seemingly random rock and say, “This was made by human hands.” There’s more or less no known natural mechanism that breaks certain kinds of rocks in a way that makes sharp edges, or knocks consistent flakes off a larger core. Spot those useful edges or flakes, and you almost certainly have an intentionally made tool. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2017]

Toolmaking, diet and brain size are all believed to have had an influence on each other. Increased brain size may have lead to tool making and better food gathering strategies, which in turn led to a better quality diet that allowed a small digestive system, which in turn freed energy for the development of an even larger brain.

Early man probably made tools with sticks, wood, horn and other perishable materials that rotted not long after they were used and thus escaped fossilization. The early Australopithecus species were believed to have used tools like bits of horn for digging and sticks for fishing out termites and other insects (as chimps and some birds do today). [Source: Michael Lemonick, Time, March 14, 1994]

See Separate Articles: OLDEST STONE TOOLS AND WHO USED THEM factsanddetails.com TOOLS FROM THE EARLY HOMO PERIOD factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone Tools”

by John C. Whittaker (1994) Amazon.com;

“Early Hominid Activities at Olduvai: Foundations of Human Behaviour”

by Richard Potts (1988) Amazon.com;

“Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Oldowan” by Erella Hovers, , David R. Braun Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Stone Tools of Eastern Africa: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“The Emergence of the Acheulean in East Africa and Beyond” y Rosalia Gallotti, Margherita Mussi Editors, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

Types of Stone Tools

Archaeologists recognize four kinds of tools, listed here in ascending order of development: 1) choppers, crude tools made by shearing one or a few pieces off a stone; 2) flake tools, implements made with numerous flakes, or small pieces chiseled off; 3) crude biface tools , ax-like tools or tools with a point made from stone, wood antler or bone that are fashioned by chipping way material from two or more sides; and 4) hand axes, which are similar to biface tools except they are made with more advanced skills. Sophisticated Acheulean hand axes are named after a French site. They were also produced in Africa and the Middle East. [Source: World Almanac]

In the 1960s, as part of an effort to make sense of the evolution of stone tools globally, Grahame Clark devised a system based on five lithic modes, based primarily on European stone tools but applied worldwide. The modes are:

Mode 1 Tools include Pebble cores and flake tools. They date to the Early Lower Paleolithic period (about 2.6 million to 1 million years ago), and embrace Chellean, Clactonian, Tayacian tools found in Western Europe.

Mode 2 Tools include Large bifacial cutting tools made from flakes and cores. They date to the later Lower Paleolithic period (about 1 million to 300,000 years ago) and embrace Abbevillian, Acheulian tools found in Western Europe.

Mode 3 Tools include Flake tools struck from prepared cores. They date to the Middle Paleolithic period (300,000 to 30,000 years ago) and embrace Levalloisian Mousterian tools found in Western Europe.

Mode 4 Tools include Punch-struck prismatic blades retouched into various specialized forms. They date to the Upper Paleolithic period (35,000 to 10,000 years ago) and embrace Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean tools found in Western Europe. The Aurignacian culture is a good example of mode 4 tool production. Long blades (rather than flakes) appeared during this time.

Mode 5 Tools include Retouched microliths and other retouched components of composite tools. They date to the Later Upper Paleolithic and Mesolithic period 15,000 to 10,000 years ago. and embrace Azilian, Magdalenian, Maglemosian, Sauveterrian, Tardenoisian tools found in Western Europe.

Stone Tool Terminology

Homo Erectus tool from China

Stone tools are the oldest surviving type of tool made by hominin, our early human ancestors. It is likely that bone and wooden tools were used quite early, but organic materials deteriorates with time and doesn’t survive like stone. Archaeologists sometimes use the term 'lithics' to refer to all artifacts made of stone. [Source: K. Kris Hirst, Thought.com, March 8, 2017]

Artifact: An artifact (also spelled artefact) is an object or remainder of an object, which was created, adapted, or used by humans. The word artifact can refer to almost anything found at an archaeological site, including everything from landscape patterns to the tiniest of trace elements clinging to a potsherd: all stone tools are artifacts.[Source: K. Kris Hirst, Thought.com, March 8, 2017]

A geofact is a piece of stone with seemingly human-made edges have been naturally broken or eroded, as opposed being shaped, modified or broken on purpose by humans or hominins. If artifacts are products of human behaviors, geofacts are products of natural forces. Distinguishing between artifacts and geofacts can be difficult. It can also be difficult distinguishing between marks made artifacts and those made geofactsm animals or natural occurrances.

An assemblage or haul refers to the entire collection of artifacts recovered from a single site. Material culture is used in archaeology and other anthropology-related fields to refer to all the corporeal, tangible objects that are created, used, kept and left behind by past and present cultures.

Stone Tool Technology

Chipped stone tools are made by knapping — which means shaping a piece of stone such as flint by striking it. Chert, flint, obsidian, silcrete or similar stone are typically knapped by flaking off pieces with a hammerstone, often made of a similar or harder material. A hammerstone is the name for an object used like a hammer knap off or make fractures on another object. Debitage [pronounced DEB-ih-tahzhs] is the collective term used archaeologists to refer to the sharp-edged waste material left over when someone makes a stone tool. It is usually knaps of flint. [Source: K. Kris Hirst, Thought.com, March 8, 2017]

1.8-million-year-old tool from Dmanisi, Georgia

Archaeologists classify stone tools into industries (also known as complexes or technocomplexes) that share distinctive technological or morphological characteristics. In 1969 in the 2nd edition of World Prehistory, Grahame Clark proposed an evolutionary progression of flint-knapping in which the "dominant lithic technologies" occurred in a fixed sequence from Mode 1 through Mode 5. He assigned to them relative dates: Modes 1 and 2 to the Lower Palaeolithic (300,000 to 70,000 years ago), 3 to the Middle Palaeolithic (70,000 to 35,000 years ago), 4 to the Upper Palaeolithic (35,000 years ago to 12,000 B.C.) and 5 to the Mesolithic (12,000 to 10,000 B.C.) . They were not to be conceived, however, as either universal—that is, they did not account for all lithic technology; or as synchronous—they were not in effect in different regions simultaneously. Mode 1, for example, was in use in Europe long after it had been replaced by Mode 2 in Africa. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Clark's scheme was adopted enthusiastically by the archaeological community. One of its advantages was the simplicity of terminology; for example, the Mode 1 / Mode 2 Transition. The transitions are currently of greatest interest. Consequently, in the literature the stone tools used in the period of the Palaeolithic are divided into four "modes", each of which designate a different form of complexity, and which in most cases followed a rough chronological order. Pre-Mode I

Chipped Stone Tool Types

Scrapers are chipped stone artifact that has been purposefully shaped with one or more sharp edges. Scrapers come in a variety of shapes and sizes, and may be carefully shaped and prepared, or simply a stone with a knapped off sharp edge. Scrapers are often used to do things like clean animals hides, butcher animal flesh, or process plant materials.

Types of scrapers 1) A burin is a scraper with a steeply notched cutting edge. 2) A denticulate is a scraper with small notched edges that protrude out like teeth. 3) A turtle backed scraper looks like a turtle when viewed from the side. One side is humped like a turtle's shell, while the other is flat. Often associated with animal hideworking. 4) A spokeshave is a scraper with a concave scraping edge

Arrowheads- Projectile Points: Archaeologists prefer the term projectile point to arrowhead to describe a stone tool fixed to the end of a shaft and shot as an arrow or any object affixed to a pole or stick of some kind, which has been fashioned for use as a weapon. Made from stone, metal, bone, or other material, projectile points have typically been used to hunt animals for food but has also been used by humans to attack or defend from attacks by other humans.

Handaxes, often referred to as Acheulean or Achuelian handaxes, are the oldest recognized stone tools. They were used between 1.7 million and 100,000 years ago. An adze (sometimes spelled adz) is a wood-working tool, similar to an axe or hachet. The shape of the adze is broadly rectangular like an axe, but the blade is attached at a right-angle to the handle rather than straight across.

Blades are chipped stone tools which are always at least twice as long as they are wide with sharp edges on the long edges.

chopping too

Other Types of Stone Tools

Drills with pointed ends and gimlets (small screw-tipped tools) are blades or flakes which have been modified for boring holes They can be identified by wear and tear on the working end and are often associated with bead making. [Source: K. Kris Hirst, Thought.com, March 8, 2017]

Tools made from ground stone, such as basalt, granite and other heavy, coarse stones, were ground, pecked, and/or polished into desired shapes. A grinding stone is a stone with a carved or pecked or ground indentation in which domesticated plants such as wheat or barley or wild ones such as nuts and were ground into flour.

The atlatl is a sophisticated combination hunting tool or weapon, formed out of a short dart with a point socketed into a longer shaft. A leather strap hooked at the far end allowed the hunter to fling the atlatl over her shoulder, the pointed dart flying off in a deadly and accurate manner, from a safe distance.

Early Hominins, Termite Munching Tools and Killer Females

2-million-year-old Oldowan

stone chopping tool Paleoanthropologist Lee Berger believes early hominins licked long blades of grass and then stuck them into the hole of a termite colony and then pulled out with full of termites. Termites are very nutritious. They have more calories for their weight than beef. After munching on a few termites, Berger told National Geographic, "Mmmm, like herbs. They're good when you're really hot. They have all this acid in them, and it makes your mouth water...They're pretty high in protein." Gore tried one, saying: "A crunch between the front teeth, a squirt, and an aftertaste I find more astringent than mmmm ."

The earliest known bone tools were used to fish out termites. Thousands of such tools have been found at the Swartkans and Sterkfontein sites in South Africa. Dated to between 1.8 millions years ago, they are believed to have been used by Australopithecus robustus. The bones are similar in size and shape and have distinctive markings made from poking them into termite mounds.

Based on observations of female chimpanzees, Jill Pruetz and Paco Bertolani of Iowa State University, theorized in a February 2007 article in the journal Current Biology that early women may have played a central role in early weapon making, perhaps to compensate for being smaller size than males. Female chimpanzees in Senegal have been seen gnawing at the end of sticks, making primitive spears which they use to hunt bush babies, small primates.

Bertolani saw a female chimp use a spear to stab a bush baby as it slept in a hollow tree and pull it out and eat it (another 21 attempts at similar kill were unsuccessful). Males were never seen using the technique. Pruetz told the Times of London, “Females have to come up with creative ways at getting at a problem, whereas males have brawn. The observation that individuals hunting with tools includes females and immature chimpanzees suggests that we should rethink traditional explanations for the evolution of such behavior in our own lineage.”

Toolmakers and Users in the Animal Kingdom

There are many examples of tool-using animals. Egyptian vultures drop stones on ostrich eggs to crack them open; elephants use sticks to rub their backs; chimpanzees and monkeys use rocks to open nuts; sea otters sometimes break open shells with rocks; and gorillas and orangutans use branches to pull down limbs with fruit.

The woodpecker finch uses a twig as a tool with extraordinary skill. First it searches around for a twig that is the right size and strength. Once it finds one it likes it jabs the twig into a hole like a lance and maneuvers it around to pry out grubs deep inside the tree, far beyond reach of its beak. Some finches, once they've found a twig they like, carry it around from tree to tree. According to researchers only about one out of five woodpecker finches have mastered the technique.♦

In 2001, Betty, a New Caledonian crow kept in the aviary at Oxford University, was the subject of an experiment to find if she would take a straight tool or a hooked one to fetch as tiny bucket with meat inside. When the hooked tool was accidently knocked away Betty took the straight tool and methodically bent it to make a hook which she used to retrieve the bucket.

In December 2009, scientists at Melbourne’s Victoria Museum released a photograph of an octopus with its legs wrapped around a coconut shell, which it used to protect itself on the sea floor. The scientists said the octopus carries the shell with it and uses it as armor in what the scientists said was the first known example of an invertebrate using tools.

See Separate Article: TOOL USE BY ANIMALS factsanddetails.com

Monkeys in Brazil Make Hominin-Like Stone Tools

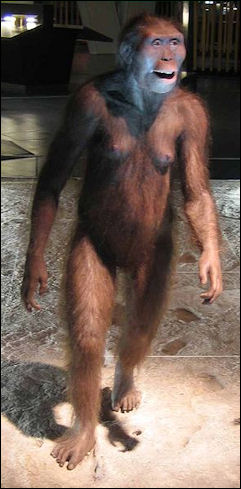

A.afarensis At a national park in Brazil scientists watched Capuchin monkeys smash stones against each other, splitting off sharp-edged flakes that resembled cutting tools early hominins. Associated Press reported: “The monkeys ignored the flakes, focusing on the damaged stones instead. So they clearly weren’t deliberately making them as tools. But if ancient monkeys did the same thing, their unintentional handiwork could be mistaken for deliberate tool-making by human ancestors, researchers said. [Source: Associated Press, October 19, 2016 -]

“The scientists are not suggesting that any stone tools attributed so far to human forerunners were instead made by monkeys, said Tomos Proffitt of Oxford University in England. Those tools, which date back as far as 3.3 million years ago, are more complex than what the Brazilian monkeys make, he said. But as scientists look for earlier and earlier tools, their findings may begin to resemble the monkey flakes more strongly, said Proffitt, lead author of a study released by the journal Nature. -

“The work shows that such flakes are not exclusively the calling card of our ancient ancestors, called hominins, he said. If somebody finds very old simple flakes, “you can’t assume it is hominin. You have to say it might be produced by an extinct monkey or ape,” Proffitt said. Our African ancestors used sharp-edged stone flakes for butchering and skinning animal carcasses, as well as cutting up tough plant material. To show such flakes were human-made tools, scientists seek evidence like wear marks on the edges or nearby animal bones with marks from butchering. -

Who Made the First Hominin Tools?

Who made the first hominin tools? Some scientists believe that “ Australopithecus “ species may have used tools. Other scientists argue that their brains were not developed enough for toolmaking, Since many of the tools were not found near any particular set of bones it is difficult to say unequivocally which species of hominin used the tools.

Scientists long thought tool-making was confined to our branch of the evolutionary family tree, the Homo group. But in 2015, scientists reported finding 3.3-millon-year-old tools much older than any known member of Homo. Maybe they were made by some smaller-brained forerunner hominin, such as Australopithecines like “Lucy.”

Australopithecus tools are thought to have been pebble tools, roughly chipped into sharp edge. Flint has been identified as the stone that gives best results. The 2.6 million-year-old flaked scraping tools and bone fragments found in the Gona region have been linked to “Australopithecus garhi” because Australopithecus garhi remains have been found relatively nearby and the remains have been dated to around the same time as tools.

It is not clear who made the Olduvai tools. “Homo habilis” remains were found nearby but were thought to have emerged 2.5 million years ago, 100,000 years after the tools. Tools resembling those found at Olduvai Gorge have been found on the western side of the Great Rift Valley in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formally Zaire) near the shores of Lake Edward. No hominin bones have been found yet however. See Homo habilis.

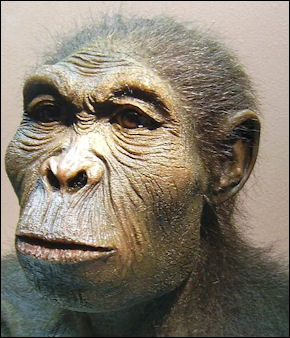

What Were the First Hominin Tools

Homo habilis There has been some debate over what actually were the first tools: the cores that had flakes chipped off them or the flakes themselves. The sharp edge seems to be the most desired trait of early stone tools and flakes often had sharper edges than the cores and were easier to make. Berkeley anthropologist Dr. Nicholas Toth told the New York Times, "the easy but now erroneous inference was that because of their different shapes, the cores were the tools." He reasoned that the sharp flakes were the tools because a rock blade becomes dull after about five minutes of cutting an animal hide. When a new blade is needed it is much easier to hammer off a flake than carve an elaborate tool. When people think of stone," he said, "they think primitive, not functional, but you can’t get anything sharper than a flake." [Source: Brenda Fowler, New York Times, December 20, 1994]

Toth told the New York Times tool used caused physiological changes in the tool users. He said that as homonids started using tools and becoming carnivores, they began to "produce simulated biological organs’slashing, crushing organs...You see a reduction in the size of the teeth and jaws because we're replacing biology through technology."

By observing how the flakes were chipped off the core Toth figures that 56 percent of them had right-handed features and 44 percent had left features. Modern humans, which are about 90 percent right-handed, are the only known animals to have such a strong preference for one hand. Toth believes that early man had brains dominated by either the right or left hemisphere.

Early Hominin Tools and Scavenging for Food

Early tools were probably used to cut meat and hides, dig up roots and tubers and smash bones in order to extract the fat-rich marrow. Some scientists believe that early tool users survived off the marrow and brains extracted from the smashed bones and skulls of scavenged animals.

These scientists believe that early toolmaker was not able to hunt and large game such as antelopes like lions and leopard. Perhaps they suggest early tool users were scavengers that used their intelligence to outwit other scavengers like hyenas and jackals. Perhaps they used tools to quickly butcher, haul off and stash carcasses before competitors could get to them.

The reasoning goes early toolmaker feed on the bone marrow of scavenged animals such as wildebeest killed by lions. These hominins were able to break open the bones with their tools, something competing scavengers were not able to do. The fatty marrow from two wildebeest legs would have provided enough calories to keep the early toolmakers going for an entire day.

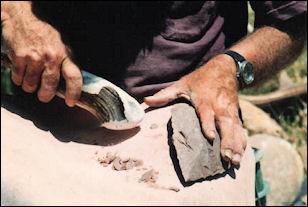

Recreating Early Tools

Recreating early toolsToth has made stone tools similar to those used by early man and used them to butcher an elephant that had died of natural causes. The flaked flint ax easily cut through the centimeter thick hide. Two men were able to butcher 100 pounds in an hour but after that the time the tools were so dull they needed resharpening. [Source: Kenneth Weaver, National Geographic, November 1985 [┹]

A team led by Helene Roche, an archaeologist from the University of Paris, pieced together 2,000 flakes from a 2.3 million-year-old site in the Rift Valley in Kenya into 60 reconstructions of original stones. Roche told AP, "It's not like they were just randomly whacking and knocking off whatever happened to come off." Roche stuck rocks to see what kinds of flakes were produced. If they weren't any good they were discarded. Her research shows that early man knew where to begin striking and how best to chip off pieces to achieve a sharp edge.

Scientists have been able to figure what tools were used for by examining wear on recreated tools produced by different materials under microscopes and comparing the wear marks to similar marks found on fossil tools. Tools used to cut meat, for example, show different wear patterns than those to work wood. Tools used to scrape hides show war patterns caused by repeated rubbing along skins.

In a groundbreaking experiment to investigate early tool use a pygmy chimpanzee, named Kanzi, made small flakes which he used to cut a rope on a box to get a banana inside. Within a month he learned how to strike the round core with a round hammer to produce a flake and later devised his own method in which he threw the cores on a hard tile floor. After a couple of tries usually a flake good enough to use as a blade broke off. One skill mastered by early homonids that Kanzi couldn't learn was that flakes chipped off at angles produced better blades.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except 1.76 million year old ax, Columbia University

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024