PRE-HOMO TOOLS

Simple Oldowan tool

The earliest tools were choppers and scrappers. For a long time the oldest recognized hominin tool was a 2.6 million-year-old flaked scraping tool found in the Gona region of Ethiopia by a team lead by Sileshi Semaw, an Ethiopian archaeologist now at Indiana University. It is not known who used the tools. Scientists believed it was Australopithecus garhi. See Australopithecus garhi.

The tools were probably used to break open bones and scrape out the marrow and perhaps to cut meat off the bones. Before this no tools had been linked with australopithecines before. Leg bone of other animals found near the tools had cut and chip marks and signs of hammering.

In 2003, Semaw’s team found 2.6 million-year-old tools among bone fragments in the Gona area. Believed to have been used to cut up meat, the tools, scientists say, shed some light on which came first tools or better diets. Semaw told the New York Times, “I believe the stone tools came first and the larger brain came later with a more substantial meat diet.”

An antelope jaw with cut marks, indicating its tongue was sliced out with a sharp stone flake was found on the Bouri Peninsuala in Lake Yardi in Ethiopia. The bones, dated to 2.5 million years ago, suggest the toolmakers used tools to scavenge meat and marrow from large animals. Curiously though no actual tools were found at the site. The discovery nearby of “Australopithecus garhi” bones indicate it again was the most likely the tool maker.

See Separate Articles: EARLY HOMININ TOOLS: WHO MADE THEM AND HOW WERE THEY MADE? factsanddetails.com ; OLDEST STONE TOOLS AND WHO USED THEM factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Flintknapping: Making and Understanding Stone Tools”

by John C. Whittaker (1994) Amazon.com;

“Prehistoric Stone Tools of Eastern Africa: A Guide” by John J. Shea Amazon.com;

“Early Hominid Activities at Olduvai: Foundations of Human Behaviour”

by Richard Potts (1988) Amazon.com;

“Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Oldowan” by Erella Hovers, , David R. Braun Amazon.com;

“The Emergence of the Acheulean in East Africa and Beyond” y Rosalia Gallotti, Margherita Mussi Editors, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

Oldowan Tools

Tools, now called Oldowan tools, were found in 2.6 million-year-old strata in forty-mile long Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. Early Olduvan tools consist of flakes of chipped rock and cores of chipped rock from which the flakes were chipped. The tools are distinguishable from naturally chipped stones because they contain the marks of repeated blows. Ethiopian archaeologist Yonas Beyene told National Geographic, "The hominins picked up one stone and broke it with another. That gave them a sharp cutting edge that could pass through animal hide’something hominin teeth could not do."

Olduvai stone chopping tool The earliest stone tools believed to have been made by the genus Homo are tools from or of the type of found in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, where they were discovered in large quantities. Oldowan tools were characterized by their simple construction, predominantly using core forms. These cores were river pebbles, or rocks similar to them, that had been struck by a spherical hammerstone to cause conchoidal fractures removing flakes from one surface, creating an edge and often a sharp tip. The blunt end is the proximal surface; the sharp, the distal. Oldowan is a percussion technology. Grasping the proximal surface, the hominid brought the distal surface down hard on an object he wished to detach or shatter, such as a bone or tuber. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The earliest known Oldowan tools date from 2.6 million years ago and were in Gona, Ethiopia. After this date, the Oldowan Industry spread throughout much of Africa. Archaeologists are currently unsure which Hominin species first developed them, with some speculating that it was Australopithecus garhi, and others saying it was Homo habilis. Homo habilis used them for a long period. About 1.9-1.8 million years ago Homo erectus inherited them. The Industry flourished in southern and eastern Africa between 2.6 and 1.7 million years ago, but also spread out of Africa and into Eurasia with homo erectus, who took Oldowan tool as far east as Java by 1.8 million years ago and Northern China by 1.6 million years ago. +

The Leakeys, who excavated Olduvai Gorge, defined a "Developed Oldowan" Period in which they believed they saw evidence of an overlap in Oldowan and Acheulean (See Below) tools. They assigned Oldowan tools with to Homo habilis and Acheulean with Homo erectus. Homo erectus was later dated to have lived as early as 2 million years ago and homo habalis lived until 1.3 million years. This meant one could not definitely say which tools belonged to which species unless bone fossils and tools were found together. In any case a wave of Acheulean tools from Africa to Eurasia and then spread across Eurasia, resulting in use of both there. H. erectus may not have been the only hominin to leave Africa; European fossils are sometimes associated with Homo ergaster, a contemporary of H. erectus in Africa. There are hints that maybe homo habalis left too. +

Oldowan Toolmakers Carefully Chose Their Materials and Designs

Scientists using robots, replica tools and stresses have determined that Oldowan tool makers carefully chose their materials and designs 2 million years ago. In the journal Royal Society Interface, a group of three archaeologists based in England and Spain surveyed tools found at Olduvai Gorge site and ran them through engineering tests to try and understand if ancient hominins were iterating better and better materials and designs. [Source: Caroline Delbert, Popular Mechanics, February 6, 2020]

The archaeologists noticed that different types of tools were made with different materials. “For more than 1.8 million years hominins at Olduvai Gorge were faced with a choice: whether to use lavas, quartzite, or chert to produce stone tools,” the researchers said. Lavas include igneous rocks like basalt and granite. Chert is a subgroup of sedimentary rock and includes flint, opal, and jasper.

Oldowon chopper

Caroline Delbert wrote in Popular Mechanics,“If toolmaking was more of an unstudied crapshoot, scientists would expect tools of all kinds to be made with all three of these families of stone. Instead, the sharpest, finest cutting tools were made of delicate, but fine-textured quartzite. Bulkier, more heavy-duty cutting tools were made from lavas. The archaeologists saw a clear pattern in toolmaking, but was that evidence-based? Were ancient hominins using kind of a scientific method?

To find out, the research team made a bunch of replica tools and found a robot to stress test them. They tested sharp cutting on lengths of PVC pipe and longer-term durable cutting on tree branches. “We quantify the force, work and material deformation required by each stone type when cutting, before using these data to compare edge sharpness and durability,” the scientists write.

“A sharp, fine cutting tool could be used for a ton of different jobs, from gathering wild food to scraping the bark off of sticks. Functionally it’s more like a knife, and while it certainly could be durable, that’s a lot less important than holding a sharp edge. Compare that with a larger cutting implement that’s usually used like an axe. An axe isn’t just sharp—it’s also a tough wedge that you must be able to bury in a log in order to keep forcing the two sides apart.

“The edge still has to be sharp, but the axe itself must be very durable and strong. You wouldn’t use a knife to cut down a tree any more than you’d use a hand axe to cut down fine grasses or peel sticks—at least not if you had a choice. “When combined with artifact data, we demonstrate that Early Stone Age hominins optimized raw material choices based on functional performance characteristics,” the scientists write. This shows that ancient hominins weren’t only making tools. They were considering what happened with past tools and making decisions based on what had worked best. That level of abstraction and logical decision-making is itself an accomplishment for a species that predated humans by more than

Oldowan Tool-Making Site at Lake Victoria, Kenya

Popular Archaeology reported: “At a site in the Homa Peninsula of Lake Victoria, Kenya, scientists are uncovering stone tools and fossils that are shedding new light on their manufacture and use, as well as early human habitat and behavior. Led by co-directors Dr. Thomas Plummer of Queens College, City University of New York and Dr. Rick Potts of the Smithsonian Institution, excavations at the site, called Kanjera South, have revealed a large and diversified assortment of Oldowan stone tools, fossil animal remains and other flora and faunal evidence that is building a picture of hominin, or early human, life and behavior in a grassland environment about 2 million years ago. Oldowan stone tools represent the earliest known human or hominin stone tool industry, named after the Olduvai Gorge, where Louis Leakey first discovered examples in the 1930’s. This early industry was typically composed of simple “pebble tools” such as choppers, scrapers and pounders, a type of technology used from about 2.6 to 1.7 million years ago. [Source: Popular Archaeology, June 12, 2012 /+]

1 million year old Oldowan tool

“According to Plummer, the site “has yielded approximately 3700 fossils and 2900 artifact...This represents one of the largest collections of Oldowan artifacts and fauna found thus far”. But more significant than the numbers is what the analysis of the finds and the site has revealed. Says Plummer, “the 2 million year old sediments at Kanjera South…..provide some of the best early evidence for a grassland dominated ecosystem during the time period of human evolution, and the first clear documentation of human ancestors forming archaeological sites in such a setting”. /+\

“The site thus shows clear evidence that early humans of this time period were inhabiting and utilizing a grassland environment, in addition to other types of environments, a signal of critical adapation that led to evolutionary success. Moreover, analysis of the makeup of the tools and the geography and geology of the area suggested that these hominins were transporting what they must have considered to be the highest quality materials from relatively distant locations to produce the most effective and efficient tools for butchering animals. /+\

“Cut marks made by stone blades on fossil bones, particularly small antelopes, showed signs that the animals may have been hunted, or at least encountered first, by the early humans before other preying animals reached the carcasses. “The overall pattern of hominin access to the complete carcasses of small antelopes may be the signal of hominin hunting”, writes Plummer. “If so, this would be the oldest evidence of hunting to date in the archaeological record”.

“Use of stone tools by these early humans apparently went beyond butchery. “Thus far, the use-wear on the quartz and quartzite subsample of Kanjera artifacts confirms that animal butchery was conducted on-site, but also demonstrates the processing of a variety of plant tissues, including wood (for making wooden tools?) and tubers. This is significant, because the processing of plant materials appears to have been quite important, but would otherwise have been archaeologically invisible”. /+\

Acheulean Tools

More complex Acheulean tools, named after the site of Saint-Acheul in France, developed 1.76 million years ago. Acheulean tools were characterized not by a core, but by a biface, the most notable form of which was the hand axe. The earliest Acheulean ax appeared in the West Turkana area of Kenya and around the same time in southern Africa. They are particularly plentiful at the Tanzanian site of Isimila. Acheulean axes are larger, heavier and have sharp cutting edges that are chipped from opposite sides into a teardrop shape. [Source: The Guardian, Wikipedia +]

Acheulean hand axes are cutting tools. They were made by Homo erectus and other early human species from about 1.76 million to 130,000 years ago, represent humanity’s most enduring technology. In contrast to an Oldowan tool, which is the result of a fortuitous and probably ex tempore operation to obtain one sharp edge on a stone, an Acheulean tool is a planned result of a manufacturing process. The manufacturer begins with a blank, either a larger stone or a slab knocked off a larger rock. From this blank the maker removes large flakes, to be used as cores. Standing a core on edge on an anvil stone, the maker hits the exposed edge with centripetal blows of a hard hammer to roughly shape the implement. Then the piece must be worked over again, or retouched, with a soft hammer of wood or bone to produce a tool finely chipped all over consisting of two convex surfaces intersecting in a sharp edge. Such a tool is used for slicing; using it for pounding would destroy the edge and cut the hand. +

Some Acheulean tools are disk-shaped, others ovoid, others leaf-shaped and pointed, and others elongated and pointed at the distal end, with a blunt surface at the end, obviously used for drilling. These tools are believed to have often been used for butchering. Not being composite (lacking haft) they are not very useful for killing. Killing had to have been done in some other way. Acheulean tools are larger than Oldowan tools. The blank was ported to serve as an ongoing source of flakes until it was finally retouched as a finished tool itself. Edges were often sharpened by further retouching.

Acheulean tool

On million-year-old hand axes excavated at Olorgesailie, Kenya, Rhitu Chatterjee of NPR wrote: The oldest innovations were axes designed to be held in the palm of the hand. They were shaped like a tear drop, with a rounded end and a pointed eye. The edges were wavy and sharp. And they look as if they were great at chopping down branches — or chopping up the carcass of a large animal.” "I think of the hand axes as the Swiss army knife of the Stone Age," Smithsonian paleoanthropologist Rick Potts told NPR. The scientists reported their findings in three studies published in the journal Science.[Source: Rhitu Chatterjee, NPR.org, March 15, 2018]

“In addition to branch- and carcass-chopping, the axes were likely used to dig for water to drink or tubers to eat. The carcasses probably belonged to large animals like the giant (now extinct) ancestors of hippos, elephants and wild pigs that roamed the grasslands back then. Potts says the ancient humans of that time likely scavenged dead animals, as their heavy, clunky hand axes wouldn't have served well for hunting big game. "These are very large tools," he says. "They might have been thrown but not very accurately." Nevertheless, these hand axes served the ancient humans well for several hundred thousand years — from 1.2 million years ago to 500,000 years ago — and the technology remained largely unchanged during the time. “

In July 2021, archaeologists revealed the discovery of North Africa's oldest Stone Age hand-axe manufacturing site, dating back 1.3 million years. The find pushed back by hundreds of thousands of years the start date in North Africa of the Acheulian stone tool industry associated with a key human ancestor, Homo erectus, researchers on the team told journalists in Rabat. [Source: AFP, September 24, 2021]

1.76-Million-Year-Old Hand Axes from Kenya: Oldest Advanced Stone Tools

In 2011, archaeologists announced that they had excavated what they believe are the oldest "advanced" stone tools yet discovered — from the banks of Lake Turkana. According to Archaeology magazine: At 1.76 million years old, the handaxes are the oldest known examples of Acheulean tools.Compared with older, cruder stone tools, the handaxes are heavier and have sharp edges for butchering, scraping, and smashing. The find raises interesting questions about which early humans first left Africa and what tool technologies they took with them. [Source: Archaeology magazine, January-February 2012]

The 1.76-million-year-old hand axes shows that early humans — with Homo erectus being the most likely candidate — were using such tools at least 300,000 years earlier than thought to perform tasks such as butchering animal carcasses. Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: “A rare haul of picks, flakes and hand axes recovered from ancient sediments in Kenya are the oldest remains of advanced stone tools yet discovered. Archaeologists unearthed the implements while excavating mudstone banks on the shores of Lake Turkana in the remote north-west of the country.[Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian August 31, 2011 |=|]

“The largest of the tools are around 20 centimeters long and have been chipped into shape on two sides, a hallmark of more sophisticated stone toolmaking techniques probably developed by Homo erectus, an ancestor of modern humans. Trenches dug at the same site revealed remains of long-gone species that shared the land with those who left the tools behind. Among them were primitive versions of hippopotamuses, rhinos, horses, antelopes, and dangerous predators such as big cats and hyenas. The stone tools, made for crushing, cutting and scraping, gave early humans a means to butcher animal carcasses, strip them of meat and crack open their bones to expose the nutritious marrow. |=|

“Researchers dated the sediments where the tools were found to 1.76 million years old. Until now, the earliest stone tools of this kind were estimated to be 1.4 million years old and came from a haul in Konso, Ethiopia. Others found in India are dated more vaguely, between 1 million and 1.5 million years old. Older, cruder stone tools have been found. The most ancient evidence of toolmaking by early humans and their relatives dates to 2.6 million years ago and includes simple pebble-choppers for hacking and crushing. These Oldowan tools, named after the Olduvai gorge in Tanzania, were wielded by our predecessors for around a million years. |=|

Who Used the 1.76-Million-Year-Old Hand Axes from Kenya

1.76 million year old tool from Kenya

Ian Sample wrote in The Guardian: ““Most Acheulian stone tools have been recovered from sites alongside fossilised bones of Homo erectus, leading many archaeologists to believe our ancestors developed the technology as an improvement on the Oldowan toolmaking skills they inherited. "The Acheulian tools represent a great technological leap," said Dennis Kent, a geologist involved in the study at Rutgers University in New Jersey and Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in New York.[Source: Ian Sample, The Guardian August 31, 2011 |=|]

“Writing in the journal Nature, a team of researchers led by Kent's colleague Christopher Lepre describe finding the stone tools in a region called Kokiselei in the Rift Valley. The site is close to where several spectacular human fossils have been found, including Turkana Boy, an early human teenager who lived 1.5 million years ago. |=|

“Unearthing the tools has raised fresh questions about the skills possessed by different groups of H. erectus as they spread across the globe. Lepre's team found both Oldowan and Acheulian stone tools at Kokiselei, but no evidence for advanced stone tools has been found at a site occupied by H. erectus 1.8 million years ago in Dmanisi in Georgia. This, Kent said, presents a problem if H. erectus originated in Africa and migrated to Asia, as many archaeologists believe. "Why didn't Homo erectus take these tools with them to Asia?" |=|

“One radical explanation offered by researchers is that H. erectus originated in Asia instead of Africa. Another possibility is that groups migrating from Africa into Asia lost the skills to make Acheulian tools along the way. Chris Stringer, head of human origins at the Natural History Museum in London and author of a new book The Origin of Our Species, said the latest haul of Acheulian tools were "very crude by the standards of later examples". "In terms of the Out of Africa event, new dating of the Dmanisi site in Georgia places some of the material from there older than 1.8 million years ago, so it is evident that human emergence from Africa preceded even this new date for bifacial tools. In fact some researchers believe the first exodus from Africa could have been even earlier than the date for Dmanisi, by a pre-erectus population making Oldowan tools," he said. |=|

"In the deep past, with small populations that were prone to local or wider extinctions, innovations did not always take hold and spread. Novelties like blade tools and bows and arrows may have been invented and reinvented many times over, due to the loss of individuals and populations, and the knowledge they carried. "So we cannot be sure that the tools found at Kokiselei were really the beginning of the establishment of the Acheulian. Populations could have experimented with bifacial working many times before it took hold more widely around 1.6 million years ago." |=|

Improved Stone Axes: A Sign of Mental Advances by Early Humans?

According to Los Alamos National Laboratory: “Stone Age man’s gradual improvement in tool development, particularly in crafting stone handaxes, is providing insight into the likely mental advances these early humans made a million years ago. Better tools make for better hunting, and better tools come from more sophisticated thought processes. Close analysis of bits of chipped and flaked stone from across Ethiopia is helping scientists crack the code of how these early humans thought over time. [Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Phys.org, March 14, 2013]

Acheulean tool from Spain

“Los Alamos National Laboratory Fellow Giday WoldeGabriel and a team of Ethiopian, Japanese, American and German researchers recently examined the world’s oldest handaxes and other stone tools from southern Ethiopia. Their observation of improved workmanship over time indicates a distinct advance in mental capabilities of the residents in the entire region, with potential impacts in tool-development skills, and in overall spatial and navigational capabilities, all of which improved their hunting adaptation. “Even though fossil remains of the tool makers are not commonly preserved, the handaxes clearly archive the evolution of innovation in craftsmanship, acquired intelligence and social behavior in a pre-human community over a million-year interval,” said WoldeGabriel.

“The scientists determined the age of the tools based on the interlayered volcanic ashes with the handaxe-bearing sedimentary deposits in Konso, Ethiopia. Handaxes and other double-sided or bifacial tools are known as the first purposely-shaped tools made by humanity and are closely associated with Homo erectus, an ancestor of modern humans. A paper in a special series of inaugural articles in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, “The characteristics and chronology of the earliest Acheulean at Konso, Ethiopia,” described their work.

“Some experts suggest that manufacturing three-dimensional symmetric tools is possible only with advanced mental-imaging capacities. Such tools might have emerged in association with advanced spatial and navigational cognition, perhaps related to an enhanced mode of hunting adaptation. Purposeful thinning of large bifacial tools is technologically difficult, the researchers note. In modern humans, acquisition and transmission of such skills occur within a complex social context that enables sustained motivation during long-term practice and learning over a possible five-year period.

Researchers observed that the handaxes’ structure evolved from thick, roughly-manufactured stone tools in the earliest period of Acheulean tool making, approximately 1.75 million years ago to thinner and more symmetric tools around 850,000 years ago. The chronological framework for this handaxe assemblage, based on the ages of volcanic ashes and sediments, suggests that this type of tool making was being established on a regional scale at that time, paralleling the emergence of Homo erectus-like hominin morphology. The appearance of the Ethiopian Acheulean handaxes at approximately 1.75 million years ago is chronologically indistinguishable from similar tools recently found west of Lake Turkana in northern Kenya, more than 125 miles to the south. “To me, the most intriguing story of the discovery is that a pre-human community lived in a locality known as Konso at the southern end of the Ethiopian Rift System for at least a million years and how the land sustained the livelihood of the occupants for that long period of time. In contrast, look at what our species has done to Earth in less than 100,000 years – the time it took for modern humans to disperse out of Africa and impose our voracious appetite for resources, threatening our planet and our existence,” WoldeGabriel said.”

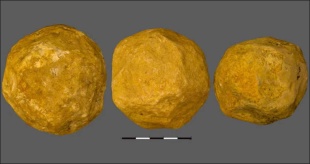

Early Humans Deliberately Made Mysterious Stone 'Spheroids' 2 Million Years Ago

In September 2023, scientists announced that early hominins deliberately made stones into spheres 1.4 million years ago in Israel, though what prehistoric people used the balls for remains a mystery. AFP reported: Archaeologists have long debated exactly how the tennis ball-sized "spheroids" were created. Did early hominins intentionally chip away at them with the aim of crafting a perfect sphere, or were they merely the accidental by-product of repeatedly smashing the stones like ancient hammers? New research led by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem suggests that our ancestors knew what they were doing.

“The team of scientists examined 150 limestone spheroids dating from 1.4 million years ago which were found at the 'Ubeidiya archaeological site, in the north of modern-day Israel. Using 3D analysis to reconstruct the geometry of the stones, the researchers determined that their sphericalness was "likely to have been produced intentionally". The early hominins — exactly which human lineage they belonged to remains unknown — had "attempted to achieve the Platonic ideal of a sphere", they said. While the spheroids were being made, the stones did not become smoother, but did become "markedly more spherical," said the study in the journal Royal Society Open Science. This is important because while nature can make pebbles smoother, such as those in a river or stream, "they almost never approach a truly spherical shape," the study said. [Source: AFP, September 6, 2023]

Julia Cabanas, an archaeologist at France's Natural History Museum told AFP that this means the hominins had a "mentally preconceived" idea of what they were doing. That in turn indicates that our ancient relatives had the cognitive capacity to plan and carry out such work. Cabanas said the same technique could be used on other spheroids. For example, it could shed light on the oldest known spheroids, which date back two million years and were found in the Olduvai Gorge of modern-day Tanzania. But exactly why our ancestors went to the effort of crafting spheres remains a mystery. Possible theories include that the hominins were trying to make a tool that could extract marrow from bones, or grind up plants. Some scientists have suggested that the spheroids could have been used as projectiles, or that they may have had a symbolic or artistic purpose. "All hypotheses are possible," Cabanes said. "We will probably never know the answer."

In 2016, Archaeology magazine reported: No animal besides humans can throw a five-ounce spheroid object more than 170 kilometers per hour (105 miles an hour). Recent experiments indicate that our facility with throwing may have been an evolutionary advantage. According to simulations, spheroids, or ball-shaped stones, found at African archaeological sites as old as 1.8 million years, appear to have been the ideal weight and size to inflict worthwhile damage to medium-sized prey animals at distances up to 25 meters (82 feet). [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, November-December 2016]

In 2024, Live Science reported: Baseball-size "spheroids" made from soft rock have been found at toolmaking sites in Africa, Asia and Europe. The earliest are up to 2 million years old, but it's not known what their purpose was. A recent study analyzed the stone spheroids mathematically and suggested they were attempts to impose spherical "symmetry" on roughly round balls of rock. The researchers didn't call these "art," but they noted that some ancient hand axes also show symmetry. [Source: Tom Metcalfe, Live Science, February 3, 2024]

With Animal Bone Tools — Was the Animal From Which They Came Important

The use of animal bone as raw material for tools dates back at least 1.8 million years but why were some animals selected for tools and other not. Justin Bradfield wrote: Animals played an important role in prehistoric societies. They were a source of food, raw material, and, sometimes, reverence. Their bones were also used to create tools — for instance, arrowheads. In several parts of the world certain animals and the tools made from their bones were held by their makers to be symbolically important. For instance, in South Africa the frequent depiction of certain animals such as eland and rhinoceros in rock art illustrates their cultural importance.

But it wasn’t clear whether and to what extent certain animals’ symbolic importance translated into other aspects of society, such as technology and tool manufacture. That’s because most bone tools recovered from archaeological excavations are so pervasively modified that it is impossible to identify the type of animal from which they were made based on anatomical markers. Archaeologists could only assume that people made tools from the same animals they preyed on for food. [Source: Justin Bradfield, University of Johannesburg, The Conversation, September 9, 2018]

Bradford was part of a 2018 study by scientists in South Africa and the U.K. that identified the animals used by people in the past to make bone arrowheads. He said: Our findings suggest that only certain animals were used for tool manufacture. Others appear to have been deliberately avoided. For example, carnivores and bush pigs appear not to have been selected for tool manufacture despite their remains being found in archaeological sites. Their apparent avoidance may have to do with cultural taboos. This is the first time a species-level identification of bone tools has been undertaken in southern Africa.

We used an analytical technique called Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry (ZooMS). This uses unique collagen peptide markers (which are the amino acids that make up the organic component of bone) to distinguish between different groups of animals. It can sometimes identify bone to the level of species. The results indicate that Bantu farmers used fewer species for tool manufacture than they hunted for food. We also found that certain animal species were used for tools that didn’t appear to have been hunted for food.

We identified a narrow range of antelope from the bone tools from nine archaeological sites from Gauteng and Limpopo. Of particular interest is the presence of sable, roan, zebra and rhino. Until now, we didn’t know that these species’ bones were used to make tools in southern Africa. Sable and roan were important sources of supernatural potency among the Bushmen. But their symbolic importance to early farmers is unknown. Rhinos, on the other hand, were an important symbol among both hunter-gatherers and farmers. Rock engravings of rhinoceros (as well as of raon, sable, sheep, wildebeest and giraffe) are common in our study area. Rhinos were likely associated with shamanism and rain making by the Bushmen, and leadership by the farmers.

Despite the symbolic importance attached to the rhinoceros, they were still actively hunted and consumed by farmers. This indicates that their symbolic significance didn’t spare them from becoming food. We also identified cattle bones at several farming sites, supporting the long-held notion that farmers used livestock bones to manufacture tools. If we accept that rock art and the animals it depicted were believed to be imbued with supernatural powers, then it is conceivable that the tools made from their bones were viewed in a similar way.

It’s worthwhile noting which species don’t appear to have been targeted for tool manufacture. There are many different animals in the study region whose bones are the correct size from which to make arrowheads. Yet, despite a wide range of animal remains found at the sites, only a fraction were used to make bone arrowheads. Most of the bone tools come from bovids. The two exceptions are zebra and rhinoceros. Why might this be?

Carnivores’ long bones, for instance, are mechanically ill-suited for impact-related tasks like arrows. That may explain why we didn’t find any bones belonging to species like jackal, leopard or lion. But we’re not sure how to explain the absence of other species, such as pigs, whose bones share the same broad mechanical properties as cows and antelopes and which are present at all the archaeological sites.

The apparent avoidance of certain animals in bone tool manufacture may be understood in terms of their bones’ fitness for purpose: that is, could it perform the desired task? Yet, it is clear that this was not their only consideration and that culturally-mediated technological strategies were likely a factor too.

1.2 Million-Year-Old Obsidian-Tool Factory in Ethiopia — Clever and the Oldest Ever Found

In 2023, scientists announced they had found the oldest obsidian-tool workshop ever found — dating back to 1.2 million years ago — on a cliff extending on one side of a valley in Ethiopia about 45 kilometers (30 miles) southwest of Addis Ababa. Aspen Pflughoeft wrote in the Miami Herald: Archaeologists noticed a large deposit of obsidian stones while studying the Melka Kunture archaeological site, according to a study published January 19, 2023 in the journal Nature. Looking closer, they noticed the obsidian pieces had been shaped into handaxes. [Source: Aspen Pflughoeft, Miami Herald, February 1, 2023]

Researchers uncovered nearly 600 stone tools, almost exclusively made of obsidian, in one section of the cliff side. The artifacts were over 1.2 million years old, the study said. Based on the weathering patterns, the tools were likely found near where they were initially buried. Analyzing the handaxes, archaeologists found a “remarkable” amount of “standardization,” the study said. Notably, the handaxes were made of obsidian, a fragile black volcanic rock that is difficult to carve. “This was a focused activity” for the hominin crafters, researchers said. “The sheer amount of handaxes and debris that had accumulated … suggest that this was an often repeated activity and even a routine one.” The tools provided evidence of “the repetitive use of fully mastered skills” by hominins, the early family of modern humans. Archaeologists concluded they uncovered a “stone-tool workshop” — the oldest ever known, according to the study.

Although tool-crafting dates back 3.3 million years, researchers believed “the use of dedicated ‘workshops’ for tool-crafting” came millennia-later, Vice reported. The finds at Melka Kunture have challenged that timeline. At Melka Kunture, “hominins were doing much more than simply reacting to environmental changes;” the study authors wrote. “They were taking advantage of new opportunities, and developing new techniques and new skills.” Excavations at the archaeological site are ongoing and led by a team of Italian and Spanish researchers.

The obsidian artifacts included more than 30 hand axes, or teardrop-shaped stone tools, averaging about 11.5 centimeters (4.5 inches) long and weighing 0.3 kilograms (0.7 pounds). Their makers may have used them for chopping, scraping, butchering and digging. But it was quite a surprise to see them made in a workshop. "This is very new in human evolution," study first author Margherita Mussi, an archaeologist at the Sapienza University of Rome and director of the Italo-Spanish archeological mission at Melka Kunture and Balchit, a World Heritage site in Ethiopia, told Live Science. Ancient hominins "are very often depicted as barely surviving, struggling with a hostile and changing environment."Here we prove instead that they were clever individuals, who did not miss the opportunity of testing any resource they discovered." [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, February 8, 2023]

900,000-Year-Old Hand Axes from Spain

Hominins living in what is now Spain fashioned double-edged stone cutting tools as early as 900,000 years ago, almost twice as long ago as previously thought. Bruce Bower wrote in Science News: “ If confirmed, the new dates support the idea that the manufacture and use of teardrop-shaped stone implements, known as hand axes, spread rapidly from Africa into Europe and Asia beginning roughly 1 million years ago, say geologist Gary Scott and paleontologist Luis Gibert, both of the Berkeley Geochronology Center in California. [Source: Bruce Bower, Science News, September 3, 2009 ~|~]

“Evidence of ancient reversals of Earth's magnetic field in soil at two archaeological sites indicates that hand axes date to 900,000 years ago in one location and to 760,000 years ago in the other, Scott and Gibert report in the Sept. 3 Nature. Until now, most researchers thought that hand axes unearthed at these sites were made between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago. ~|~

900,000-year-old hand ax from Spain

“Other European hand ax sites date to no more than 500,000 years ago. In contrast, hand axes date to roughly 1.7 million years ago in eastern Africa. And age estimates of 1.2 million years and 800,000 years for hand axes from two Israeli sites indicate that this tool-making style spread out of Africa long before the origin of Homo sapiens around 200,000 years ago. Excavations in southern China have also yielded 800,000-year-old hand axes (SN: 3/4/00, p. 148). Fossils from ancient human ancestors have not been found with the Israeli and Chinese artifacts.~|~

“Earlier analyses of magnetic reversals in soil at other sites in southern Spain indicate that single-edged stone tools appeared there around 1.3 million years ago, Gibert says (SN: 1/4/97, p. 12). Population movements back and forth between Africa and Europe must have occurred at that time, possibly via vessels across the Strait of Gibraltar, he hypothesizes. "Then at 900,000 years ago, we now have the oldest evidence of hand axes in Europe, which represents a second migration from Africa that brought a new stone-tool culture," Gibert says. ~|~

“Scott and Gibert's "surprisingly old ages" for the Spanish hand axes bring the chronology of ancient Europe's settlement in line with that of Asia, remarks archaeologist Wil Roebroeks of Leiden University in the Netherlands. Europe contains relatively few stone-tool sites from around 1 million years ago, making it difficult to reconstruct the timing of ancient population pulses into the continent, Roebroeks says. ~|~

“Although new estimated ages for soil layers at the Spanish sites appear credible, the suggestion that hand axes there are by far the oldest in Europe "is extremely daring, to put it mildly," comments archaeologist Robin Dennell of the University of Sheffield in England. In his view, the precise depth of the hand axes when they were unearthed several decades ago remains unclear. It's possible that these finds actually came from soil layers that Scott and Gibert place at no more than 600,000 years old, Dennell says. ~|~

“Scott and Gibert first identified the geological position of specific magnetic reversals in sediment at an ancient lakeshore near the Spanish sites. Dates for these reversals have already been established in previous studies. The researchers compared these magnetic shifts to those at the hand ax sites to date the tools. These data provide minimum ages for the Spanish finds. "Older ages are possible but would be odd," Gibert says.” ~|~

Changing Tool Technologies and Mass Production

According to Cambridge University: The primitive technologies that our early ancestors left behind change over time, and comparing finds dated to different times can advance understanding of our evolutionary trajectory. “We think the evolution to modern humans is associated with changes in behaviour and in technology, for example in their tool use,” said Mirazón Lahr. “We’ve already found evidence that they started using animal bones to make tools, which was rare in earlier populations.”

“The people who lived around this lake 10,000 years ago used microliths — a form of miniaturised stone tool technology,” said R.A. Foley. “Instead of producing one or two big flakes like the earliest modern humans, they produced lots of very small flakes to make composite tools. This is a sign of the flexibility of the way modern humans adapted to different conditions. We’ve also found a beach in the Turkana Basin from about 200,000 years ago and that has its own very different fossilised fauna, and very different stone tools. The technology and the people changed a lot over the past 200,000 years.”

Archaeology magazine reported: The plateau atop a sandstone outcrop called Messak Settafet in Libya in the central Sahara could be the earliest example of an entire landscape created and modified by humans. Archaeologists found an average of 75 lithics per square meter — a carpet of stone tools and man-made fragments spanning hundreds of thousands of years and perhaps thousands of square miles. The finds demonstrate just how important tool technologies were for early hominins, and that the area was likely a magnet for stone-hungry populations across the region. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2015]

Smaller More Diverse Tools Become Common Place Around 320,000 Years Ago

Rhitu Chatterjee of NPR wrote: “around 320,000 years ago, the ancient humans seem to have switched to an entirely new technology. The scientists found numerous smaller, flatter, sharper stone tools. "We see a smaller technology, a more diverse series of stone tools," says Potts. These tools were designed for specific purposes — some were used as blades, some as scrapers or spear heads. Scientists reported their findings in three studies published in Science.[Source: Rhitu Chatterjee, NPR.org, March 15, 2018 +++]

“The new studies also show that by 320,000 years ago this technology was well established in the region, suggesting that human ancestors likely started developing it even earlier. It is the full-blown Middle Stone Age," Lahr says. "They have stone tools that are small, that are prepared and retouched, that are made with technique thought to come hundreds of thousands of years later." +++

“The diversity of stone tools from the Middle Stone Age suggests advanced thinking and planning. "The flakes are being much more carefully prepared for a particular purpose," says Alison Brooks, an anthropologist at George Washington University and an author of the three studies. "They are fairly small in size, compared to the technology of earlier people. And in addition, they are made with much finer grained material," which allowed them to better control shapes and sizes of the stone tools."We see the ability to produce small triangular points, that look like they were projectile points," says Potts. "They were tapered at the end, so that could have been put on the shaft of something that flew through the air." In other words, a potentially lethal spear. +++

Lower Paleolithic tools

“So our ancestors likely shifted from scavenging to hunting. An analysis of the fossilized animal bones found in the sediments show that people in that period were eating a range of mammals — which were by now much smaller, and closer in size to the animals of today — including hares, rabbits and springbok and even a couple of species of birds and fishes, says Brooks. And they weren't just picking up nearby stones to create their weapons. Earlier hand axes were made primarily from volcanic basalt, sourced within 2 to 2.5 miles of where these humans lived. The latter weapons were made of stones like obsidian, which originated far from Olorgesailie. A small stone point made of non-local obsidian. The chemical composition of the artifact matches obsidian sources as far as 55 miles away. "That black obsidian, that rare rock was being transported, brought in in chunks, from 15 to 30 miles away," says Potts. "We have a couple of rocks that were brought from up to 55 miles away." +++

“These distances are far greater than what modern-day hunter gatherers travel over the course of a year, he says. "They weren't just traveling long distances and chipping rocks as they go," he adds. "If they did that, then there would have just been small chips of obsidian left at the archaeological sites where we dig. Instead we see large pieces of raw material coming in. The rocks were shaped at Olorgesaile itself." That kind of exchange of raw materials is a tell-tale sign of exchange between different groups of people, the scientists say. "In the Middle Stone Age, we begin to see the early stages of social networks, of being aware of another group and exchanging rocks over longer distances." Potts and his colleagues also find evidence of exchange of brightly colored red and black rocks that were then drilled into, possibly to extract pigment. This is the earliest evidence of the extraction of pigments, says Lahr. It's also evidence of a complex culture, where the ancient humans probably used pigments symbolically — perhaps to paint themselves, or their hides, or weapons. And where different groups exchanged raw materials (and possibly food). +++

“There's that same kind of exchange today, says Brooks, referring to hunter gatherer groups like the Hadza people of northern Tanzania. "They deliberately maintain distant contacts with people in these other groups," she says. They have strategies to maintain these contacts — either by encouraging their children to marry into these other groups, or they take trips to visit the groups, to maintain ties by giving gifts. "It's a way of building up these distant contacts, which are extremely important for their survival." During times of stress, when food or water is scarce, people from one group can disperse and take shelter with other groups that they've cultivated a relationship with. "So the networks are like money in the bank, or wheat in your silo or cows in your barn," says Brooks. "They don't have any other way of saving for a rainy day." +++

“And as she and her colleagues show, the beginning of the Middle Stone Age in Kenya was preceded by a long and tumultuous phase in the region. "Things were going haywire, in terms of the development of geological faults, earthquake activity that moved the low places high and the high places low," says Potts. "It changed the shape of the landscape." This was accompanied by repeated cycles of droughts and high rainfall. "And it is precisely during those time periods that we expect to see hunting and gathering people to move further distances," says Potts, "and to begin to nurture relationships with groups beyond their own group." It is no different than what humans all over the world do today, he adds. When times are tough, we look for greener pastures. The archaeological records from the Middle Stone Age at Olorgesailie reveal "the roots of that kind of migration," he says.” +++

Change from Acheulean to Middle Stone Age Tool Technology 500,000 to 300,000 Years Ago

Richard Potts of the Smithsonian wrote: At Olorgesailie, a well-known hominin site in Kenya “our scientific team has found evidence that’s potentially related to the origin of Homo sapiens in the form of a critical transition from one technology to another. The older technology is typified by large, oval cutting implements called handaxes. Typical of what’s called Acheulean stone technology, nearly two dozen layers of these handaxes and other Acheulean tools have been unearthed at Olorgesailie. They span an immense period of about 700,000 years, covering a time when fossil remains show that the hominin species Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis inhabited eastern Africa. The last Acheulean archeological sites at Olorgesailie are 500,000 years old, at which point there is a frustrating 180,000-year gap in these sediments caused by erosion. The archaeological record starts up again around 320,000 years ago, as sediments began to fill in the landscape. [Source: Richard Potts, Director of the Human Origins Program, Smithsonian Institution, The Conversation, October 21, 2020]

But the Acheulean was gone. In its place was Middle Stone Age technology, consisting typically of smaller, more easily carried implements than the clunky Acheulean handaxes. In other areas of Africa, the Middle Stone Age technology is associated with the earliest African Homo sapiens. These toolmakers often used sharp-edged black obsidian as a raw material. Archaeologists Alison Brooks, John Yellen and others chemically traced the obsidian to distant outcrops in several different directions, up to 95 kilometers away from Olorgesailie. They concluded that the far-off obsidian sources provide evidence of resource exchange among groups, a phenomenon unknown in Acheulean times. Our Middle Stone Age excavations also contained black and red coloring materials. Archaeologists view pigments like these as signs of increasingly complex symbolic communication. Think of all the ways people use color – in flags, clothing and the many other ways people visually claim their identity as part of a group.

So here we had the extinction of the Acheulean way of life as well as its replacement by dramatically new behaviors including technological innovations, intergroup exchange of obsidian and the use of pigments. But we had no way to examine what happened in the 180,000-year gap when this transition took place.

Were Tool Technology Changes Influenced by Geological Activity?

Richard Potts of the Smithsonian wrote: Different types of sediment are laid down in lakes, streams and soils, and the sediment layers tell the story of changing environments over time. Geologists Kay Behrensmeyer and Alan Deino joined me in the field in southern Kenya to figure out where we might drill for sediments that could fill in the Olorgesailie time gap. The drill team extracted a cylinder of earth, just four centimeters in diameter, that turned out to represent 1 million years of environmental history. Human Origins Program, Smithsonian The result was a core 139 meters deep containing a sequence of ancient lake and lake margin habitats and soils, all riddled with volcanic layers we could date to yield the most precisely dated East African environmental record for the past 1 million years. [Source: Richard Potts, Director of the Human Origins Program, Smithsonian Institution, The Conversation, October 21, 2020]

The sediment record showed that during the era 1 million to 500,000 years ago, when Acheulean toolmakers were busy in the Olorgesailie basin, ecological resources were relatively stable. Fresh water was reliably available. Grazing zebra, rhinoceros, baboons, elephants and pigs altered the regional vegetation of wooded grassland to create short, nutritious grassy plains. We determined that right around 400,000 years ago, a critical environmental transition took place. From a relatively stable setting, we started to see repeated fluctuation in the vegetation, available water and other ecological resources on which our ancestors and other mammals depend.

According to the anthropological literature, hunter-gatherers today and in recent history respond to periods of uncertain resources by investing time and energy to refine their technology. They connect with distant groups to sustain networks of resource and information exchange. And they develop symbolic markers that strengthen these social connections and group identity. Sound familiar? These behaviors resemble how the ancient Middle Stone Age lifestyle at Olorgesailie differed from the Acheulean way of life.

Equally notable, the large grazing species typical of Acheulean times became extinct after 500,000 years ago. Between 360,000 and 300,000 years ago, ecologically flexible herbivore species smaller in size, less water-dependent and reliant on both short and tall grass and tree leaves, had replaced the specialized grazers such as now-extinct species of zebras and the huge baboon. These changes in the animal community reflect the advantage of adaptable diets, a parallel to how our Middle Stone Age ancestors adjusted to environmental uncertainty.

For the past two decades, many human origins researchers have thought of climate as the primary, if not sole, driver of hominin adaptive evolution. Our new study draws attention, though, to several factors in the Acheulean-Middle Stone Age transition in southern Kenya. Yes, rainfall varied strongly after the environmental transition 400,000 years ago. But the terrain across the region also became fractured by tectonic activity and blanketed with volcanic ash. And big herbivores exerted different influences on the vegetation before and after this transition.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except 1.76 million year old ax, Columbia University, and stone spheroids from the Royal Society Open Science

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024