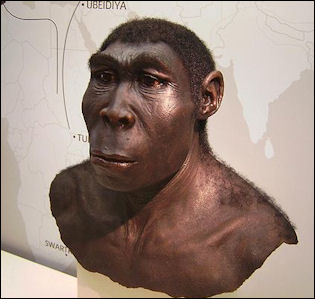

HOMO ERECTUS

Homo erectus “Homo erectus” had a considerably larger brain than “Homo habilis, its predecessor. It fashioned more advanced tools (double-edged, teardrop-shaped "hand axes" and "cleavers" ) and controlled fire (based on the discovery of charcoal with erectus fossils). Better foraging and hunting skills, allowed it to exploit its environment better than “Homo habilis”

Homo erectus survived for as long as 1.9 million years. Paleontologist Alan Walker told National Geographic, “Homo erectus was the velociraptor of its day. If you could look one in the eyes, you wouldn't want to. It might appear to be human, but you wouldn't connect. You'd be prey."

Homo erectus, regarded as a direct ancestor of modern humans, is thought to have left Africa almost 2 million years ago and spread across Asia and probably Europe. It disappeared from Africa around 400,000 years ago but lived on the island of Java. In 2020, a team used new technology on previously excavated remains to confirm that 12 H. erectus skulls from Ngandong. Java were between 117,000 and 108,000 years old, making them the last known members of their species. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March -April 2020]

Homo erectus was the first of our relatives to have body proportions like a modern human. It may have been the first to harness fire and cook food. L.V. Anderson wrote on Slate.com: It’s thought that both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens evolved from H. erectus, with Neanderthals emerging about 600,000 years ago (and going extinct around 30,000 years ago) and modern humans emerging around 200,000 years ago (and still going strong). Neanderthals were shorter and had more complex societies than H. erectus, and they’re thought to have been at least as large-brained as modern humans, but their facial features protruded a little more and their bodies were stouter than ours. It’s thought that Neanderthals died out from competing, fighting, or interbreeding with H. sapiens.” [Source: L.V. Anderson, Slate.com, October 5, 2012 \~/]

Nickname: Peking Man, Java Man. Geologic Age 2 million years to 100,000 years ago. Homo erectus “ lived at the same time as “Homo habilis “ and “Homo rudolfensis” and later at the same time as Neanderthals and modern humans, but not necessarily in the same places. Linkage to Modern Man: Regarded as a direct ancestor of modern man, May have had primitive language skills. Discovery Sites: Africa and Asia. Homo erectus“ fossils have been found in eastern Africa, southern Africa, Georgia, Algeria, Morocco, China and Java.

See Separate Articles: HOMO ERECTUS TOOLS, HUNTING AND VIOLENCE factsanddetails.com ; HOMO ERECTUS LIFE, LANGUAGE, ART AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; HOMININS, HOMO ERECTUS AND FIRE factsanddetails.com ; HOMO ERECTUS FOOD factsanddetails.com ; HOMININS, HOMO ERECTUS AND COOKING factsanddetails.com ; HOMO ERECTUS AND OUT OF AFRICA THEORY factsanddetails.com ; DMANISI HOMININS —1.8-MILLION-YEAR-OLD HOMO ERECTUS IN GEORGIA factsanddetails.com ; HOMO ERECTUS AND THE FIRST HOMININS IN ASIA factsanddetails.com ; HOMO ERECTUS AND THE FIRST HOMININS IN EUROPE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“In search of Homo erectus: a Prehistoric Investigation: The humans who lived two million years before the Neanderthals” by Christopher Seddon (2017) Amazon.com;

“The Evolution of Homo Erectus: Comparative Anatomical Studies of an Extinct Human Species” Amazon.com;

“Peking Man” Amazon.com;

“Java Man : How Two Geologists' Dramatic Discoveries Changed Our Understanding of the Evolutionary Path to Modern Humans” by Roger Lewin , Garniss H. Curtis, et al. Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala, Camilo J. Cela-Conde Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013) Amazon.com;

“Almost Human: The Astonishing Tale of Homo Naledi and the Discovery That Changed Our Human Story” by Lee Berger, John Hawks, et al. Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

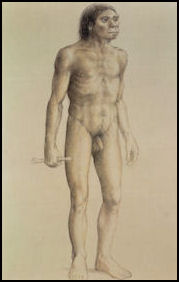

Homo Erectus Size

Homo erectus Size: The tallest hominin species until modern man. The body looked almost like a modern human. males: 1.78 meters (5 feet 10 inches) tall, 139 pounds (63 kilograms) females: 1.6 meters (5 feet 3 inches) tall, 53 kilograms (117 pounds). “Homo erectus” was considerably larger than its forebears. Scientists speculate that the reason for this is that they ate more meat.

Brain Size: 800 to 1000 cubic centimeters. Enlarged over the years from the size of a one -year-old infant to that of a 14-year-old boy (about three-fourths the size of a modern adult human brain). A 1.2-million-year-old skull from Olduvai Gorge had a cranial capacity of 1,000 cubic centimeters, compared to 1,350 cubic centimeters for a modern human and 390 cubic centimeters for a chimp.

In an August 2007 article in Nature, Maeve Leakey of the Koobi Fora Research Project announced her team had found a well-preserved, 1.55-million-year-old skull of a young adult “Homo erectus “ east of Lake Turkana in Kenya. The skull was the smallest ever found of the species which indicated that “Homo erectus” may not have been as advanced as had been previously thought. The finding does not challenge the theory that “Homo erectus” are the direct ancestors of modern humans. But does make one step back and wonder could such an advanced creature such a modern man evolved from such a diminutive, small-brained creature such as “Homo erectus”.

The finding shows that if nothing else there is great degree of variation in the size of “Homo erectus” specimens. The fossils were found several years before but extra care was taken identifying the species and dating the fossils, which was done from volcanic ash deposits.

Susan Anton, an anthropologist at New York University and one of the authors of the discovery, said that the variation in sizes is particularly noticeable between males and females and the finding seems to suggest that sexual dimorphism was present among “Homo erectus”. Daniel Leiberman, a Harvard anthropology professor, told the New York Times, “the small skull has got to be female, and my guess is all the previous erectus we have found turn out to be male.” If this turns out to be true then it could turn out that “Homo erectus” had a gorilla-like sex life like that of “Australopithecus robustus” (See Australopithecus robustus).

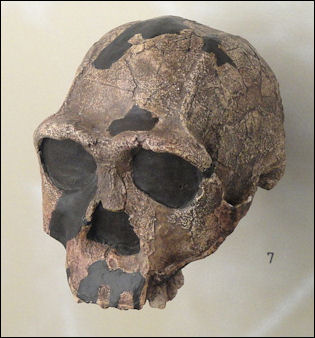

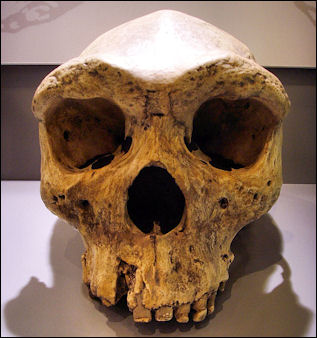

Homo Erectus Skull and Body Features

Skull Features: Thickest skull of all homonids: long and low and resembling a "partially deflated football." More similar to predecessors than modern man, no chin, protruding jaw, low and heavy braincase, thick browridges, and backward sloping forehead. Compared to its predecessors there was a reduced size and projection of the face, including much smaller teeth and jaws than those of Paranthropus and loss of the skull crest. A bony nasal bridge suggests a nose that projected like ours. “Homo erectus” was the first hominin to have asymmetrical brains like modern humans. The frontal lobe, where complex thinking takes place in modern humans, was relatively underdeveloped. The small hole in vertebrae probably meant that not enough information was transferred from the brain to the lungs, neck and mouth to make speech possible.

Body Features: Body similar to modern humans. It had long-limbed proportions common in tropical people. Tall, lean and slim hipped, it had a rib cage virtually identical to that of modern humans and strong bones able to withstand the wear and tear of a hard life on the savannah.

“Homo erectus was about five to six feet tall. Its narrow pelvis, changes in the hips and arched foot meant that it could move more efficiently and quickly on two legs than even modern humans. The legs grew longer relative to the arms, indicating more efficient walking and perhaps running,It almost certainly could run like modern humans. It's large size meant it had a large surface area able to dissipate tropical heat through sweating.

Homo erectus's teeth and jaws were smaller and less powerful than its predecessors because meat, its main food source, is easier to chew than coarse vegetation and nuts eaten by its predecessors. It was most likely a hunter well adapted for the open grasslands of savannah Africa.

Thick Homo Erectus Skulls

Homo erectus skull Homo erectus's skull was surprisingly thick — so thick in fact that some fossil hunters have mistaken it for a turtle shell. The top and sides of the cranium had thick, bony walls and a low, a wide profile, and in many ways resembled a bicycle helmet. Noel T. Boaz and Russell L. Ciochon wrote in in Natural History magazine, Many differences in hominid skulls can be accounted for by the evolution of the brain and the chewing apparatus. Large skulls are needed to contain large brains, and large jaws and teeth for processing tough foods need heavy-duty skull bones to anchor massive chewing muscles. Unfortunately, neither of these tried-and-true explanations can entirely account for the unique attributes of the H. erectus skull. What seems more likely is that the species badly needed some protective headgear. [Source: Noel T. Boaz and Russell L. Ciochon, Natural History magazine, February 2004]

The H. erectus skullcap is described technically as pachyostotic (“thick-boned”): thick, solid layers of bone make up both its inner and outer surfaces. Sandwiched between them is a less strong, latticelike layer of bone, whose intervening spaces, in life, would have been filled with marrow and blood. The H. erectus skull also has a number of unique bony structures. Three of them, namely a beetling brow ridge and bony thickenings on the sides and rear of the cranium, form a bony ring starting above the eyes, extending back around the head above the ears, and meeting on the back of the head. The top of the skull resembles the inverted bottom of a boat, with a thickened bony mound that looks like the boat’s keel extending along the midline of the skull.

When a person is injured in the head today, whether or not the skull is fractured often makes the difference between life and death. What might seem like a relatively minor break in the skull can tear blood vessels that adhere tightly to its inside surface. The buildup of blood under the skull, known as a hematoma, pushes on the brain. Coma and, eventually, death can result.

Are Thick Homo Erectus Skulls Adaptions to Battles Between Males

Scientists have long wondered why the skull was so helmet-like and it didn’t offer much protection against predators that killed mostly by bites to the neck. Recently it has been suggested that a thick skull offered protection against other homo erectus, namely males who battled each other, perhaps by bashing each other with stone tools aimed at the head. On some erectus skulls there is evidence that suggests the head may have been struck with repeated heavy blows.

Noel T. Boaz and Russell L. Ciochon wrote in in Natural History magazine, But what special sources of traumatic injury did hominids face that might have encouraged the evolution of such a robust skull? We don’t think it was exposure to predators (which can readily attack other, more vulnerable parts of the body), or a habit of venturing into slippery or precarious territory where the hazards of falling were increased. In examining the protection afforded by the H. erectus skull, we think the evidence points to some kind of violence perpetrated within the species itself.[Source: Noel T. Boaz and Russell L. Ciochon, Natural History magazine, February 2004]

Broken Hill skull from Zambia

In modern skulls one of the commonest kinds of fracture is the so-called eggshell. The concussion caused by a fall or by a blow from a blunt object can crack and push a section of cranial vault inward without disjointing the bone. The bone may remain depressed, but in an eggshell fracture, the bone—pulled by skin, muscle, and other tissues attached to the scalp—springs back to nearly its original shape. In either case, though, the damage is done. Branches of the blood vessels serving the meninges, or fibrous coverings of the brain, begin to bleed. As the hematoma expands and begins to compress the brain, sometimes hours after the injury, neurological symptoms become progressively severe.

In addition to the skullcap, other features of the H. erectus skull and jaws seem well adapted for defense against trauma. René Le Fort, a French surgeon working at the turn of the twentieth century, studied and classified the pattern of facial fractures in modern people. A Le Fort type I fracture is one that results from a blow to the upper face that breaks the bone forming an eye socket. H. erectus not only had a heavy brow ridge but also a remarkably flat and horizontal roof to the eye socket. That eye-socket covering would have been particularly hard to break because any impact there would have been transmitted straight back to the base of the skull.

Franz Weidenreich was trained as a medical doctor, and worked most of his career in medical institutions in Germany. He even served briefly as a medic in the German army during the First World War. Doubtless, then, he had more than a passing familiarity with the devastating effects of head trauma—a familiarity that became invaluable when he began to analyze the skulls of Peking man. In those fossil specimens he identified a number of depressed fractures that had subsequently healed. In other words, half a million years or so after these hominids had sustained massive blows to the head, Weidenreich had suddenly stumbled on evidence that could still reveal not only the kind of trauma that resulted, but also, because the trauma victims had survived, the protective value of their skulls

Some of the damage Weidenreich first attributed to hominids he later ascribed to carnivores. Other damage was clearly geological: some bones have been crushed by overlying sediment, others bear the impressions of rocks pushed into them as they themselves turned to stone. But in the end, Weidenreich classified some ten depressions or defects in the skulls as having been caused by blows from other hominids. We agree. The damage closely matches in size, form, and even location the healed depressed fractures seen in human skulls today.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Headstrong Hominids Natural History magazine

Homo Erectus Tools

tools found at

Konso-Gardula, Ethiopia Hand axes are usually associated with “Homo erectus”. Ones found at Konso-Gardula, Ethiopia are believed to be between 1.37 and 1.7 million year old. Describing a primitive 1.5- to 1.7-million-year-old ax, Ethiopian archaeologist Yonas Beyene told National Geographic, "You don't see much refinement here. They've only been knapped away a few flakes to make the edge sharp." After displaying a beautifully-crafted ax from a perhaps a 100,000 year later he said, "See how refined and straight the cutting edge has become. It was an artform for them. It wasn't just for cutting. Making these is time-consuming working."

Thousands of primitive hand 1.5-million- to 1.4-million-year-old hand axes have been Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania and Ubeidya, Israel. Carefully-crafted, sophisticated 780,000-year-old hand axes have been unearthed in Olorgesaile, near the Kenya and Tanzania border. Scientists believe they were used to butcher, dismember and deflesh large animals like elephants.

Sophisticated “ Homo erectus “ teardrop-shaped stone axes that fit snugly in the hand and had a sharp edged created by careful shearing of the rock on both sides. The tool could be used to cut, smash and beat.

Big symmetrical hand axes, known as Acheulan tools, endured for more than 1 million years little changed from the earliest versions found. Since few advances were made one anthropologists described the period in which “Homo erectus” lived as a time of “almost unimaginable monotony.” Acheulan tools are named after 300,000-year-old hand axes and other tools found in St. Acheul, France.

See Separate Articles: HOMO ERECTUS TOOLS. LANGUAGE, ART AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com ; EARLY HOMININ TOOLS: WHO MADE THEM AND HOW WERE THEY MADE? factsanddetails.com ; OLDEST STONE TOOLS AND WHO USED THEM factsanddetails.com

Homo Erectus Footprints Reveal They Walked Like Modern Humans

In the mid 2010s, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig discovered multiple assemblages of 1.5-million-year-old Homo erectus footprints in northern Kenya that provide unique opportunities to understand locomotor patterns and group structure through a form of data that directly records these dynamic behaviours. Novel analytical techniques used by the Max Planck Institute and an international team of collaborators, have demonstrated that these H. erectus footprints preserve evidence of a modern human style of walking and a group structure that is consistent with human-like social behaviours. [Source:Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Science Daily,July 12, 2016]

Max-Planck-Gesellschaft reported: “Fossil bones and stone tools can tell us a lot about human evolution, but certain dynamic behaviours of our fossil ancestors — things like how they moved and how individuals interacted with one another — are incredibly difficult to deduce from these traditional forms of paleoanthropological data. Habitual bipedal locomotion is a defining feature of modern humans compared with other primates, and the evolution of this behaviour in our clade would have had profound effects on the biologies of our fossil ancestors and relatives. However, there has been much debate over when and how a human-like bipedal gait first emerged in the hominin clade, largely because of disagreements over how to indirectly infer biomechanics from skeletal morphologies. Likewise, certain aspects of group structure and social behaviour distinguish humans from other primates and almost certainly emerged through major evolutionary events, yet there has been no consensus on how to detect aspects of group behaviour in the fossil or archaeological records.

Homo georgicus?

“In 2009, a set of 1.5-million-year-old hominin footprints was discovered at a site near the town of Ileret, Kenya. Continued work in this region by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and an international team of collaborators, has revealed a hominin trace fossil discovery of unprecedented scale for this time period — five distinct sites that preserve a total of 97 tracks created by at least 20 different presumed Homo erectus individuals. Using an experimental approach, the researchers have found that the shapes of these footprints are indistinguishable from those of modern habitually barefoot people, most likely reflecting similar foot anatomies and similar foot mechanics. "Our analyses of these footprints provide some of the only direct evidence to support the common assumption that at least one of our fossil relatives at 1.5 million years ago walked in much the same way as we do today," says Kevin Hatala, of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and The George Washington University.

Based on experimentally derived estimates of body mass from the Ileret hominin tracks, the researchers have also inferred the sexes of the multiple individuals who walked across footprint surfaces and, for the two most expansive excavated surfaces, developed hypotheses regarding the structure of these H. erectus groups. At each of these sites there is evidence of several adult males, implying some level of tolerance and possibly cooperation between them. Cooperation between males underlies many of the social behaviours that distinguish modern humans from other primates. "It isn't shocking that we find evidence of mutual tolerance and perhaps cooperation between males in a hominin that lived 1.5 million years ago, especially Homo erectus, but this is our first chance to see what appears to be a direct glimpse of this behavioural dynamic in deep time," says Hatala.

Endurance Running Key Part of Human Evolution

Many scientists believe large brains developed relatively rapidly hand in hand with scavenging and endurance runners. Our upright posture, relatively hairless skin with sweat glands allow us to keep cool in hot conditions. Our large buttocks muscles and elastic tendons allow us to run long distance more efficiently than other animals. [Source: Abraham Rinquist, Listverse, September 16, 2016]

According to the “endurance running hypothesis,” first proposed in the early 2000s, long-distance running played a critical role in the development of our current upright body form. Researchers have suggested that our early ancestors were good endurance runners — presumably using the skill to efficiently cover large distances in search of food, water and cover and maybe methodically chase down prey and — and this characteristic left an evolutionary mark on many parts of our bodies, including our leg joints and feet and even our heads and buttocks. [Source: Michael Hopkin, Nature, November 17, 2004 ||*||]

Michael Hopkin wrote in Nature: “Early humans may have taken up running around 2 million years ago, after our ancestors began standing upright on the African savannah, suggest Dennis Bramble of the University of Utah and Daniel Lieberman of Harvard University. As a result, evolution would have favoured certain body characteristics, such as wide, sturdy knee-joints. The theory may explain why, thousands of years later, so many people are able to cover the full 42 kilometres of a marathon, the researchers add. And it may provide an answer to the question of why other primates do not share this ability. ||*||

“Our poor sprinting prowess has given rise to the idea that our bodies are adapted for walking, not running, says Lieberman. Even the fastest sprinters reach speeds of only about 10 metres per second, compared with the 30 metres per second of a cheetah. But over longer distances our performance is much more respectable: horses galloping long distances average about 6 metres per second, which is slower than a top-class human runner. "Everyone says humans are bad runners, because when you think of running you tend to think of sprinting," he adds. "There's no question we're appalling sprinters, but we're quite good at endurance running."||*||

See Separate Article: FIRST HOMININS AND BIPEDALISM: COSTS, BENEFITS AND RUNNING factsanddetails.com

Last Homo Erectus

Skull from Sangiran

Research appears to indicate that the last place homo erectus survived was on of Java. Archaeology magazine reported: A team used new technology on previously excavated remains to confirm that 12 H. erectus skulls from Ngandong were between 117,000 and 108,000 years old, making them the last known members of their species. [Source: Archaeology magazine, March -April 2020]

At first the Homo erectus fossils found at Ngandong were thought to be between 100,000 and 300,000 years old. Then it was reported the fossils were found strata dated between 27,000 and 57,000 years old. This implied that “Homo erectus” lived much. much longer than anyone thought and “Homo erectus” and “Homo sapiens” existed at the same time on Java. Many scientists were skeptical about the 27,000-to-57,000-years-old Ngandong dates and they were ultimately tossed.

See Solo Man, Ngandong and the Last Homo Erectus Under JAVA MAN AND HOMO ERECTUS IN INDONESIA factsanddetails.com

Homo Erectus Subspecies or Related Species

There are a number of homo erectus subspecies and many paleontologists believe that a number of hominins classified as separate species that during or near the time of homo erectus are in fact homo erectus. Noel T. Boaz and Russell L. Ciochon wrote in Natural History magazine, “The skullcaps discovered in eastern Asia tend to be more robust than the ones in Africa. Hence some paleoanthropologists have regarded the African fossils as a distinct species, which they call H. ergaster. But one African skullcap just as robust as any Asian specimen was discovered by Louis Leakey in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania. It dates from about 1.4 million years ago. And even the strapping youth known as Turkana boy, the most complete H. erectus skeleton discovered so far, probably would have had a thick skull when fully grown. In any case, there is little doubt that H. erectus was on the line that ultimately led to the first modern humans. Whether that further evolution took place in Africa or was a more widespread phenomenon is a matter of debate, but one way or another we got bigger brains and thinner skulls.[Source: Noel T. Boaz and Russell L. Ciochon, Natural History magazine, February 2004]

Homo erectus subspecies or possibly closely related species include: 1) homo erectus erectus (Dubois 1891), the Javanese specimens labeled Java Man that were classified as a distinct subspecies in the 1970s; 2) homo erectus e. georgicus (Gabounia 1991, a hypothetical subspecific designation based on Dmanisi fossils from Georgia; 3) homo erectus pekinensis (Black and Zdansky 1927), originally assigned the type of Sinanthropus based on a single molar and popularly known as Peking Man; 4) homo erectus hexianensis (Huang 1982), based on the Hexian cranium found in Hexian, China; 5) homo erectus mauritanicus (Arambourg 1954), a subspecies that has received limited use as a descriptor for the cranial and mandibular material discovered at Tighenif, Algeria; 6) H. e. narmadensis (Sonakia 1984), the name given to the Narmada cranium found in India. [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article: HOMO ERECTUS SUBSPECIES, RELATED SPECIES AND FAMOUS FOSSILS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: All Posters com 2) Peking Man skull, Wesleyan University ; 3) Peking Man cave, World Heritage Site website; 4) Peking Man bust, World Heritage Site website ; Others Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024