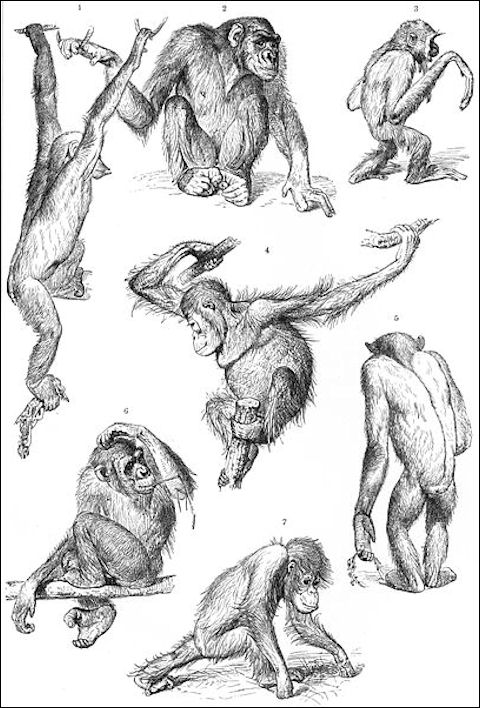

EARLY APE-LIKE PRIMATES

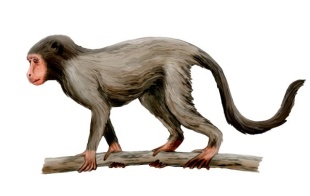

One of the earliest primates so far discovered is a 33 million year old arboreal animal nicknamed the "dawn ape" found in the Egypt's Faiyum Depression. This fruit-eating creature — Aegyptopithecus zeuxis — weighed about eight pounds (three kilograms) and had a lemur-like nose, monkey-like limbs and the same number of teeth (32) as apes and modern man.

Fossils of 20.6 million-year-old common ancestor of man and apes was unearthed in Uganda in the 1960s. The animals was about 1.2 meters tall and weighed between 40 and 50 kilograms and was described by thought as a "cautious climber."

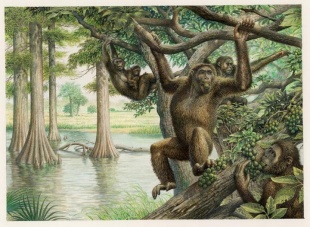

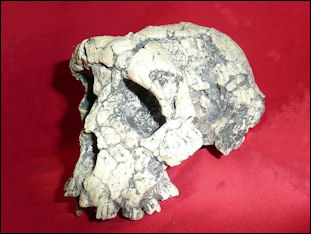

In 2011, Reuters reported: Ugandan and French scientists had discovered a fossil of a skull of a tree-climbing ape from about 20 million years ago in Uganda's Karamoja region. The scientists discovered the remains in July while looking for fossils in the remnants of an extinct volcano in Karamoja, a semi-arid region in Uganda's northeastern corner. "This is the first time that the complete skull of an ape of this age has been found. It is a highly important fossil," Martin Pickford, a paleontologist from the College de France in Paris, said. [Source: Elias Biryabarema, Reuters, August 2, 2011]

Pickford said preliminary studies of the fossil showed that the tree-climbing herbivore, roughly 10-years-old when it died, had a head the size of a chimpanzee's but a brain the size of a baboon's, a bigger ape. Bridgette Senut, a professor at the Musee National d'Histoire Naturelle, said that the remains would be taken to Paris to be x-rayed and documented before being returned to Uganda. Uganda's junior minister for tourism, wildlife and heritage said the skull was a remote cousin of the Homininea Fossil Ape.

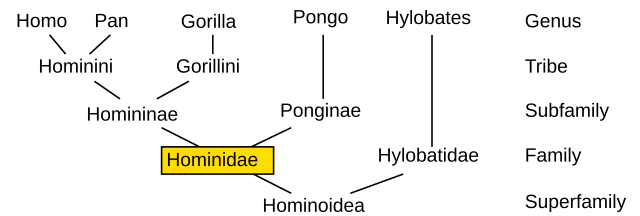

The orangutans are the only surviving species of the subfamily Ponginae, which diverged genetically from the other hominids (gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans) between 19.3 and 15.7 million years ago.

See Gigantopithecus Under PRIMATES — MONKEYS, MACAQUES, GIBBONS, AND LORISES—IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“The Link: Uncovering Our Earliest Ancestor” by Colin Tudge with Josh Young Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Fossil Men: The Quest for the Oldest Skeleton and the Origins of Humankind” By Kermit Pattison (2021) Amazon.com

“The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the Past” by Meave Leakey with Samira Leakey (2020) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

“Masters of the Planet, The Search for Our Human Origins” by Ian Tattersall (Pargrave Macmillan, 2012) Amazon.com;

Apes Become More Human-Like

Baboon-size apes that lived in East Africa about 15 million years ago may have spent most of their time on the ground. This finding is based on the hand, finger arm and shoulder bones from a ape called Equatorious found in 1993 in the Tugen Hills of north central Kenya. A fossil of an ape that lived 13 million years ago in Spain has been described as a common ancestor to all apes and hominins and led some to theorize that the ancestral ape that spawned gorillas, chimpanzees and human came to Africa from Eurasia.

Between 11 million and 8 million years ago gorillas split off from chimpanzees and humans. In 2007 an Ethiopian and Japanese team of scientists announced in a Nature article that they had found a 10-million-year-old ape 170 kilometers south of Addis Ababa in Ethiopia that was very similar to a gorilla that provided some grounds for pushing back the date of the split between humans and apes. The discovery also supported the theory that the apes that spawn humans originated in Africa.

Rudapithecus was the name given to a 10-million-year-old great ape unearthed in Hungary. Some have called the ape the closest fossil hunters gave come to finding a common ancestor of humans and African apes. Named after the village of Hungarian Rudabanya, near where it was found, it had a body and brain about the size of a chimpanzee. Its long arms and curved fingers indicate it spent a lot of time hanging from the branches of trees. Modest-size molars and thin tooth enamel suggested it ate soft fruits.

Human Ancestors Evolved Elbows and Shoulders 'Brakes' for Climbing Down Trees?

Jennifer Nalewicki wrote in Live Science: Humans have ape ancestors to thank for their flexible shoulders and elbows, which may have evolved as a natural braking mechanism for tree-scaling. Scientists made the discovery while watching numerous videos of chimpanzees and sooty mangabey monkeys, which are much more distantly related to both chimps and humans, climb up and down trees in the wild. In the new study, the researchers noticed that although both animals ascended trees similarly with their shoulders and elbows closely bent toward their bodies as they swiftly reached from one branch to the next, they differed in their techniques for descending. [Source: Jennifer Nalewicki, Live Science, September 14, 2023]

The findings suggest that chimps and humans may have flexible shoulder and elbow joints as a way to "counteract" the effects of gravity on their heavier lower bodies. The result was a finely calibrated braking system that decreased their risk of falling while they descended downward high in the treetops, according to the study, published Sept. 6 in the journal Royal Society Open Science. While mangabeys were less flexible, the chimps extended their arms above their heads while descending — similar to the way a person goes down a ladder. This maneuver was a way for the primates to slow their descents as gravity pulled them downward, the team said in a statement. "[We] noticed that while both chimpanzees and mangabeys climbed trees in a clipped motion where they didn't fully extend their joints, in downclimbing the mangabeys continued this clipped motion, while the chimps did not," co-author Mary Joy, a biological anthropology major who graduated from Dartmouth University in 2021 and made this her undergraduate thesis, told Live Science. "The two had very different ranges of motions."

Human and chimpanzee ancestors diverged approximately 6 million to 7 million years ago, while the mangabey's monkey ancestor diverged from apes around 30 million years ago.But the study suggests that flexible appendages had evolved by the time of the last common ancestor between chimps and humans, but after apes and monkeys diverged. This flexibility would have proven beneficial for things that involved specific movements like gathering food, hunting and defending themselves, according to the study.

This marks the first time researchers have extensively studied how great apes descended trees; previously, most studies were focused on them climbing. "We knew generally that chimps had an increased range of motion in their shoulders and elbows, while mangabeys did not," Joy said. This is because mangabeys and other monkeys are built similarly to quadrupedal mammals like cats and dogs, which walk on all fours and have "deep, pear-shaped shoulder sockets," the team said in the statement. The inner crook of their elbows also protrudes, making the joint resemble the letter "L," according to the statement. These joints may offer stability, but they lack a good range of motion.

Upon analyzing the joints in existing chimp skeletons that were part of museum collections, researchers noticed that the angle of the apes' shoulders was 14 degrees greater when they were descending versus when they were climbing. Their arms also extended outward at the elbow 34 degrees more when the chimps were going down trees, according to the study.This change in motion not only helped the chimps slow the pull of gravity but also allowed them to decelerate safely."Chimps can get out of trees and climb downward without having to keep their shoulder and elbow muscles under tension, which results in the exertion of a lot of energy," Joy said. "As humans, the introduction of this increased range of motion had a lot of benefits, like letting us raise our arms above our heads or throwing a ball. This motion is a legacy of evolutionary pressure on our ancestors, which gave us the ability to do a lot of things."

Split Between Apes and Hominins

Based on DNA evidence in blood proteins, molecular biologists guess that the hominin line split off from the ape line between 5 and 8 million years ago, a period of time in which little is known about apes or hominins and there is little data in the fossil record.

The generally accepted assumption is that gorillas and ancestors of chimpanzees and humans split around 6 million to 8 million years ago. Some DNA evidence seems to indicate that hominins and chimpanzees split between 5.5 million and 6.5 million years ago.

Calculations made by geneticists based on the differences between genomes indicates that the chimpanzees and hominins diverged no later than 6.3 million years ago and probably earlier than 5.4 million years ago. This finding raises questions about fossils that are more than five million years old — namely “Sahelanthropus tchadensis” and “Orrorin tugenensis" — that are claimed to belong to hominin species.

A team led by David Reich of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts has suggested that one explanations for the discrepancy between the fossil record (that says the oldest hominin are 7 million years old) and genetic evidence (which dates hominin and chimpanzee divergence at around 5.3 million years ago) is that chimpanzees and early hominin might have had sex with each other and interbred. That could also explain why some early hominins have strange mixture of human and chimpanzee traits. One should not jump to too many conclusions though as there is still a lot of uncertainty over dating and inferences made from small quantities of fossils.

Last Common Ancestor of Humans and Chimpanzees

The last common ancestor of humans and apes such as chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans and gibbons lived during the Miocene epoch (23 million to 5 million years ago). At this point it is a theoretical construct as no fossils of it have been found. Scientists believe the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees had shoulders similar to those of modern African apes, a finding supports the theory that early humans moved away from life in trees gradually. Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: “The human lineage diverged from that of chimpanzees, humanity's closest living relative, about 6 million or 7 million years ago. Knowing the characteristics of the last common ancestor of humans and chimps would shed light on how the anatomy and behavior of both lineages evolved over time, "but fossils from that time are rare," said lead author of the new study Nathan Young, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, San Francisco. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, September 8, 2015 +]

“There are currently at least two competing scenarios for what the last common ancestor might have looked like. One suggests that similarities seen in modern African apes, such as in chimps and gorillas, were inherited from the last common ancestor, meaning that modern African apes may reflect what the last common ancestor was like. "A lot of people use chimpanzees as a model for the last common ancestor," Young told Live Science. The other scenario suggests these similarities instead evolved independently in modern African apes, and that the last common ancestor may have possessed more-primitive traits than those seen in modern African apes. For instance, instead of knuckle-walking on the ground like chimps and gorillas do, the last common ancestor may have swung and hung from tree branches like orangutans, which are Asian apes. Humans aren't the only species that have evolved and changed over time — chimpanzees and gorillas have evolved and changed over time, too, so looking at their modern forms for insights into what the last common ancestor was like could be misleading in a lot of ways," Young said. +\

“The ancestral state of the shoulder is key to understanding human evolution, because the shoulder is linked to many important shifts in behavior in the human lineage. Shoulder evolution could help show when early human ancestors began using tools more, spent reduced time in trees and learned to throw weapons. However, the human shoulder possesses a unique combination of features that makes it difficult to reconstruct the body part's history. For instance, while humans are most closely related to knuckle-walking chimps, in some respects the human shoulder is more similar in shape to that of tree-dwelling orangutans. +\

“To see what the shoulder of the last common ancestor might have looked like, researchers generated 3D shoulder models from museum specimens of modern humans, chimps, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, gibbons and monkeys. The scientists compared these data with 3D models that other scientists previously generated of ancient, extinct relatives of modern humans, such as Australopithecus afarensis, Australopithecus sediba, Homo ergaster and Neanderthals. +\ Australopithecines such as Australopithecus afarensis and Australopithecus sediba are the leading candidates for direct ancestors of humans. "Recent data from the australopithecines helped us now test different models of human evolution," Young said. +\

“The scientists found the strongest model showed the human shoulder gradually evolving from an African apelike form to its modern state. "We found australopithecines were perfect intermediate forms between African apes and modern humans," Young said. This finding suggests the human lineage experienced a long, gradual shift out of the trees and increased reliance on tools as it became more terrestrial, he said. "These results pretty much confirm that the simplest explanation for how the human shoulder evolved is the most likely one," Young said. The scientists detailed their findings online Sept. 7, 2015 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.” +\

Imaging What the Last Common Ancestor Between Humans and Apes Looked Like

We don’t know what our last common ancestor (LCA) looked liked. Determining its size and what its skull, brain, legs, arms and fingers looked like is all educated guesswork, mainly based on looking at the closest equivalents alive — gorillas, chimpanzees and gibbons. Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: One big unknown is the LCA's size, said Christopher Gilbert, a paleoanthropologist at Hunter College of City University of New York, told Live Science. That's because ape fossils from the period during which the LCA lived are scarce, a 2017 study in the journal Nature noted. Early or "stem" apes span a large range of body sizes, from small gibbon-size species to larger primates approaching gorilla-size, making it difficult to pin down the heft of the LCA without a better understanding of the evolutionary relationships and history of these species, said Gilbert, who co-authored the Nature study. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, July 4, 2023]

SahelanthropusThe LCA was likely a four-legged animal, current evidence suggests. Fossils indicate that stem apes were capable of climbing vertically and of having suspensory behavior, just as modern humans can use their arms to hang from tree branches. However, unlike all living apes, which prefer to live hanging below or among tree branches, at least some stem apes were not specialized for suspensory behavior, lacking adaptations such as long, highly curved fingers and toes, and highly mobile wrists, shoulder and hip joints. This implies the LCA may not have been specialized for suspension either, Gilbert said. Some researchers have occasionally speculated "that maybe the LCA was a biped," moving on two legs like a human,Thomas Cody Prang, a paleoanthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told Live Science. However, because "the LCA was a quadruped, like other primates, "it's likely that it didn't walk on two legs but rather used all fours.

Stem apes displayed a range of head shapes. Some had skulls like gibbons with short faces while others had longer faces resembling primitive apes and Old World monkeys, such as baboons (genus Papio) and macaques (genus Macaca), Gilbert said. Still, "we know with near-certainty that the brain size of the LCA was smaller than a human's brain size," Prang said. Because it was a quadruped, the head wouldn't have sat on top of the body like a biped's does, but positioned more forward like a gorilla or chimp.

The arms and legs of early apes often are not well-preserved in the fossil record. Still, "the upper limbs of early hominins [humans and our close relatives and ancestors] appear to be large and heavily built, which is associated with forelimb-dominated locomotion — that is, climbing and suspension," Prang said. As for the legs, early hominins appear to have had short hind limbs, more like great apes — gorillas (Gorilla gorilla and Gorilla beringei) , chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), orangutans (genus Pongo) and bonobos (Pan paniscus) — than humans, he noted. In essence, early hominins appear to be built for tree canopies, not the open savanna.

In terms of the hand, in a 2021 study in the journal Science Advances, Prang and his colleagues analyzed Ardipithecus, a 4.4 million-year-old early fossil hominin, and found its hand "was most similar to chimpanzees and bonobos among all living humans, apes, and monkeys." This in turn, may suggest the LCA had long, curved finger bones.

Humans, chimps, gorillas and bonobos all walk with their heels touching the ground, suggesting the LCA did the same, Prang said. This form of movement is also often linked with other traits seen in living African apes — gorillas, chimps and bonobos — such as using knuckles to help in walking, and evolutionary adaptations to climb vertically. "All of the traits that we can reasonably study suggest that the earliest hominins, and therefore probably the LCA, were characterized by these same components of this adaptive package," Prang said. "The LCA was neither a gorilla nor a chimpanzee, but it was likely most similar to gorillas and chimpanzees among all known primates." In all, the appearance of the LCA "is still all quite contentious," Gilbert said. Filling in the picture will require new fossil discoveries.

Earliest Hominins

Sahelanthropus tchadensisThe first human-like traits to appear in the hominin fossil record are bipedal walking and smaller, blunt canines. The brains sizes of the earliest hominins was not all that different from apes such as orangutans, chimpanzees and gorillas.

Changes from an ape-like anatomy to a hominoid one become apparent in fossils from the late Miocene Period (10.4 million to 5 million years ago) in Africa. Some hominoid species from this period have traits that typical of humans but are not seen in the other living apes, leading paleoanthropologists to infer that these fossils represent early members of the hominin lineage. [Source: Nature]

The oldest fossils that have been widely accepted at least of possibly belonging to hominin species are 7-million-year-old Sahelanthropus tchadensis and 6-million-year-old Orrorin tugenensis. Many though think these fossils belong to ape species not hominin ones. (See Early Hominins)

See Separate Article: EARLIEST HOMININS AND OLDEST HUMAN ANCESTORS: ARDIPITHECUS (ARDI), SAHELANTHROPUS AND ORRORIN factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024