EARLY HOMOS

Homo ergaster Members of the genus homo have larger brains and a smaller, ape-like faces. What distinguished them from their predecessors was is ability to make stone tools. “Homo erectus” was the first species to expand into Asia and Europe. “Homo” is Latin for "human." [Sources: Homo erectus, National Geographic, May, 1997; Homo erectus, Rick Gore, National Geographic, July 1997]

Claims to the oldest “Homo” fossils include a 2.4-million-year- old mandible from Uraha, Malawi, a 2.4-million-year-old skull fragment from Lake Baringo, Kenya and a 2.3-million-year-old upper jawbone from Hadar, Ethiopia. For the most part though the period between two million and three million years ago there is little data and few fossils.

A fossilized mandible reported in 2015 may be the earliest-known member of the genus Homo. Archaeology magazine reported: It dates to around 2.8 million years ago, or 500,000 years earlier than the next oldest known examples. This period in human evolution — the transition from Australopithecus to Homo — is still not well understood. The bone and teeth have traits that appear to bridge the earlier (rounded chin) and later (slimmer molars) species. It may be a key finding for understanding the origins of our genus. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2015]

“Homo” species had longer bodies than the short and stocky “Australopithecus “ species. Since about 1.8 years hominins have been within the size range of modern humans. Male and females size differences characteristic of Australopithecus species decreased. The brain volume of Australopithecus species ranged between 400 and 500 cubic centimeters while the brain volume of early “ Homo” species was between 600 and 750 cubic centimeters.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“In search of Homo erectus: a Prehistoric Investigation: The humans who lived two million years before the Neanderthals” by Christopher Seddon (2017) Amazon.com;

“Peking Man” Amazon.com;

“Java Man : How Two Geologists' Dramatic Discoveries Changed Our Understanding of the Evolutionary Path to Modern Humans” by Roger Lewin , Garniss H. Curtis, et al. Amazon.com;

“Processes in Human Evolution: The journey from early hominins to Neanderthals and modern humans” by Francisco J. Ayala, Camilo J. Cela-Conde Amazon.com;

“Evolution: The Human Story” by Alice Roberts (2018) Amazon.com;

“Perspectives on Our Evolution from World Experts” edited by Sergio Almécija (2023) Amazon.com;

“Discovering Us: Fifty Great Discoveries in Human Origins” By Evan Hadingham (2021) Amazon.com;

“Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past” by David Reich (2019) Amazon.com;

“Stone Tools in Human Evolution”

by John J. Shea (2016) Amazon.com;

“Our Human Story: Where We Come From and How We Evolved” By Louise Humphrey and Chris Stringer, (2018) Amazon.com;

“Lone Survivors: How We Came to Be the Only Humans on Earth” by Chris Stringer (2013) Amazon.com;

“Almost Human: The Astonishing Tale of Homo Naledi and the Discovery That Changed Our Human Story” by Lee Berger, John Hawks, et al. Amazon.com;

“An Introduction to Human Evolutionary Anatomy” by Leslie Aiello and Christopher Dean (1990) Amazon.com;

“Basics in Human Evolution” by Michael P Muehlenbein (Editor) (2015) Amazon.com;

“Ancestral DNA, Human Origins, and Migrations” by Rene J. Herrera (2018) Amazon.com;

“Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind” by Yuval Noah Harari (2011) Amazon.com;

Websites and Resources on Hominins and Human Origins: Smithsonian Human Origins Program humanorigins.si.edu ; Institute of Human Origins iho.asu.edu ; Becoming Human University of Arizona site becominghuman.org ; Hall of Human Origins American Museum of Natural History amnh.org/exhibitions ; The Bradshaw Foundation bradshawfoundation.com ; Britannica Human Evolution britannica.com ; Human Evolution handprint.com ; University of California Museum of Anthropology ucmp.berkeley.edu; John Hawks' Anthropology Weblog johnhawks.net/ ; New Scientist: Human Evolution newscientist.com/article-topic/human-evolution

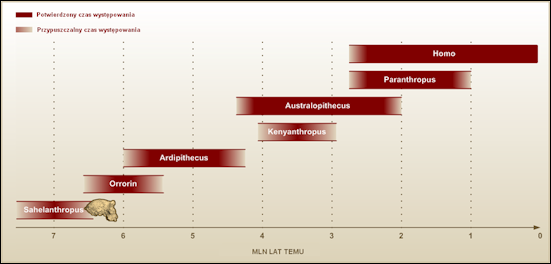

Development of Australopithecus Into Homo

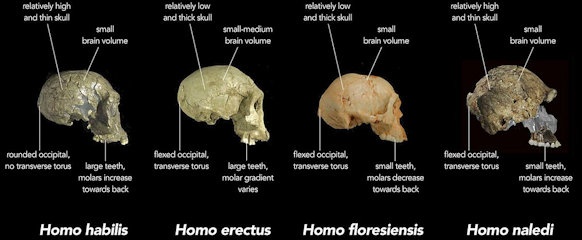

Homo Habilis skulls scientists have different theories about which hominins evolved into more developed species and which lead to evolutionary dead ends. Some scientists believed that the “Homo” genus evolved from “Australopithecus afarensis” . Others believe it developed from “Australopithecus afarensis” . “Bosei” and “robustus” are believed to be evolutionary dead ends because they lived at the same time as “Homo” species. The various theories are difficult to prove.

There is some debate as to whether the Homo genus evolved in East Africa or evolved in southern Africa and migrated north. Proponents of the southern Africa theory believe that the earliest “Homo” species evolved from “A. africanus “ (Taung Child) and base their argument on the facts that arrangement of her teeth and brain size are similar to that of “Homo habilis “ (the earliest “Homo” species), their fingers are humanlike and their brains were of similar size to “ Homo habilis” .

In southern Africa, the oldest-known hominin species is Australopithecus africanus. The four-foot-tall hominid with long arms for tree climbing lived in the region 3.3 million to 2.1 million years ago, when the area was partly forested. As the climate became drier, the forests gave way to more open grasslands, and new hominids evolved. Paranthropus robustus— famous for its massive jaw and giant molars, which allowed the species to chew tough plants—inhabited the area 1.8 million to 1.2 million years ago. It lived alongside the taller, more modern-looking Homo erectus, which also came onto the scene about 1.8 million years ago before disappearing from Africa 500,000 years ago. [Source: Erin Wayman, Smithsonian Magazine, January 2012]

One of the primary outstanding mysteries of human evolution is the origin of our genus, Homo, between two million and three million years ago. Jamie Shreeve wrote in National Geographic: “On the far side of that divide are the apelike australopithecines, epitomized by Australopithecus afarensis and its most famous representative, Lucy, a skeleton discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. On the near side is Homo erectus, a tool-wielding, fire-making, globe-trotting species with a big brain and body proportions much like ours. Within that murky million-year gap, a bipedal animal was transformed into a nascent human being, a creature not just adapted to its environment but able to apply its mind to master it. How did that revolution happen?/+\ [Source: Jamie Shreeve, National Geographic, September 2015 /+]

“The fossil record is frustratingly ambiguous. Slightly older than H. erectus is a species called Homo habilis, or “handy man”—so named by Louis Leakey and his colleagues in 1964 because they believed it responsible for the stone tools they were finding at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. In the 1970s teams led by Louis’s son Richard found more H. habilis specimens in Kenya, and ever since, the species has provided a shaky base for the human family tree, keeping it rooted in East Africa. Before H. habilis the human story goes dark, with just a few fossil fragments of Homo too sketchy to warrant a species name. As one scientist put it, they would easily fit in a shoe box, and you’d still have room for the shoes.” /+\

Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand, “has long argued that H. habilis was too primitive to deserve its privileged position at the root of our genus. Some other scientists agree that it really should be called Australopithecus. But Berger has been nearly alone in arguing that South Africa was the place to look for the true earliest Homo. And for years the unchecked exuberance with which he promoted his relatively minor finds tended only to alienate some of his professional colleagues. Berger had the ambition and personality to become a famous player in his field, like Richard Leakey or Donald Johanson, who found the Lucy skeleton. Berger is a tireless fund-raiser and a master at enthralling a public audience. But he didn’t have the bones.” /+\

Several Homo Species Lived at the Same Time

Although modern humans are the only members of the Homo genus alive today, other human species that belonged to the genus lived in the past. The earliest Homo specimen found so far lived about 2.8 million years ago. About a dozen Homo species have been identified although there is still intense debate as to how they all fit on the evolutionary tree or even whether they are unique species. Some of them, including Neanderthals, lived at the same as modern humans around 50,000 years. Others lived when modern humans were emerging around 300,000 years ago. And others still lived at the same time as Australopithecines more than 2 million years ago.

Valerie Ross wrote in Discover: “The big-brained, upright primates of the genus Homo—the group to which we modern-day humans belong—evolved in East Africa around 2.4 million years ago. By half a million years later, Homo erectus, from whom we’re directly descended, was walking the plains near Lake Turkana in what is now Kenya. But anthropologists have increasingly come to believe that Homo erectus wasn’t the only hominin around. Three newly discovered fossils, detailed in Nature in August 2012, confirm that at least two other Homo species lived nearby—providing the strongest evidence yet that several evolutionary lineages split off in the genus’s early days. [Source: Valerie Ross, Discover, August 9, 2012 )=(]

“These new discoveries bolster the idea that the human family tree wasn’t, as scientists once thought, a steady climb upward; even within our own genus, life was branching out in several directions. As anthropologist Ian Tattersall told the New York Times, “it supports the view that the early history of Homo involved vigorous experimentation with the biological and behavioral potential of the new genus, instead of a slow process of refinement in a central lineage.”“ )=(

Complexity of the Hominin Scene 3 Million Years Ago

Pete Spotts wrote in Christian Science Monitor: “New fossils from Ethiopia are providing fresh evidence that some 3 million to 4 million years ago, ancestors to modern humans may have been more diverse than previously thought. That diversity would have led to an inadvertent test to see which species was best able to weather changes in climate and habitat during that period, some researchers suggest. So far, that would appear to be Australopithecus afarensis, represented by its most famous example, Lucy, discovered in 1974 by Donald Johanson and Tom Gray. [Source: Pete Spotts, Christian Science Monitor, May 27, 2015]

range of homo habilis

“But Lucy and her species were not the only Australopithecines on the block. Over the years, researchers have reported uncovering two additional species from this period. If this latest discovery holds up, it would bring to four the number of known Australopithecus species living within this million-year span. These species range from Ethiopia to Chad. The research team that found the new fossils – upper and lower jaws that included teeth – have classified the find as belonging to a new species of hominin, a subset of hominins that includes modern humans and our direct ancestors. The researchers suggest that the new species, which they have dubbed Australopithecus deyiremeda, was a close relative to A. afarensis. The team's analysis appeared the journal Nature.

“A. deyiremeda's remains were found at a site in Ethiopia's Afar region known as Woranso-Mille, about 22 miles north of another site rich in A. afarensis fossils – pointing to the possibility that the two species roamed the same general region at about the same time. With several Australopithecus species living in eastern and central Africa in the same general period, "we're looking at hominins who are potential candidates as human ancestors," says Henry Bunn, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. During this period, known as the middle Pliocene, the climate was getting cooler and drier. Vegetation and food resources were changing.

“Looking at these Australopithecines, "you could almost think of them as ecological experiments as populations try to exploit new habitats and new resources successfully," says Dr. Bunn, who was not a member of the research team. "Most of those species went extinct."

In the past, researchers had broken the last 5 million years of hominin evolution into blocks of 1 million to 2 million years, he explains. Based on the fossil evidence available at the time, "you only had one species per block of time," he says. At about 2 million years ago, with the emergence of the genus Homo, hominins became more diverse.

With Lucy and subsequent discoveries, it now appears that the middle Pliocene also hosted a diverse array of hominins that included at least one additional group beyond Australopithecines – a group represented by Kenyanthropus platyops. The newly discovered jawbones and teeth – dated to between 3.5 and 3.3 million years ago – shared some characteristics with A. afarensis and others with K. platyops. This period also coincides with the appearance of the earliest stone tools yet found, a discovery announced last week in another paper in Nature.

“The new species is yet another confirmation that Lucy’s species, Australopithecus afarensis, was not the only potential human ancestor species," according to Yohannes Haile-Selassie, curator of physical anthropology at The Cleveland Museum of Natural History who headed the team making the discovery. “Current fossil evidence from the Woranso-Mille study area clearly shows that there were at least two, if not three, early human species living at the same time and in close geographic proximity,” he said in a prepared statement.

Body Structure of Early Homo Species Very Diverse

Research in the mid 2010s has revealed that not only did early Homo species Homo rudolfensis, Homo habilis and Homo erectus have significant differences in facial features, they also differed throughout other parts of their skeletons and had distinct body forms. According to the University of Missouri-Columbia, a research team found 1.9 million-year-old pelvis and femur fossils of an early human ancestor in Kenya, revealing greater diversity in the human family tree than scientists previously thought. "What these new fossils are telling us is that the early species of our genus, Homo, were more distinctive than we thought. They differed not only in their faces and jaws, but in the rest of their bodies too," said Carol Ward, a professor of pathology and anatomical sciences in the MU School of Medicine. "The old depiction of linear evolution from ape to human with single steps in between is proving to be inaccurate. We are finding that evolution seemed to be experimenting with different human physical traits in different species before ending up with Homo sapiens." [Source: University of Missouri-Columbia, Science Daily, March 9, 2015 /~/]

Oldowan chopper

“Three early species belonging to the genus Homo have been identified prior to modern humans, or Homo sapiens.Homo rudolfensis and Homo habilis were the earliest versions, followed by Homo erectus and then Homo sapiens. Because the oldest erectus fossils that have been found are only 1.8 million years old, and have different bone structure than the new fossil, Ward and her research team conclude that the fossils they have discovered are either rudolfensis or habilis. /~/

Ward says these fossils show a diversity in the physical structures of human ancestors that has not been seen before."This new specimen has a hip joint like all other Homo species, but it also has a thinner pelvis and thighbone compared to Homo erectus," Ward said. "This doesn't necessarily mean that these early human ancestors moved or lived differently, but it does suggest that they were a distinct species that could have been identified not just from looking at their faces and jaws, but by seeing their body shapes as well. Our new fossils, along with the other new specimens reported over the past few weeks, tell us that the evolution of our genus goes back much earlier than we thought, and that many species and types of early humans coexisted for about a million years before our ancestors became the only Homo species left." /~/

“A small piece of the fossil femur was first discovered in 1980 at the Koobi Fora site in Kenya. Project co-investigator Meave Leakey returned to the site with her team in 2009 and uncovered the rest of the same femur and matching pelvis, proving that both fossils belonged to the same individual 1.9 million years ago. /~/

Journal Reference: Carol V. Ward, Craig S. Feibel, Ashley S. Hammond, Louise N. Leakey, Elizabeth A. Moffett, J. Michael Plavcan, Matthew M. Skinner, Fred Spoor, Meave G. Leakey. Associated ilium and femur from Koobi Fora, Kenya, and postcranial diversity in early Homo. Journal of Human Evolution, 2015; DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.01.005

Oldowan Tools

The earliest stone tools believed to have been made by the genus Homo are tools from or of the type of found in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, where they were discovered in large quantities. Oldowan tools were characterized by their simple construction, predominantly using core forms. These cores were river pebbles, or rocks similar to them, that had been struck by a spherical hammerstone to cause conchoidal fractures removing flakes from one surface, creating an edge and often a sharp tip. The blunt end is the proximal surface; the sharp, the distal. Oldowan is a percussion technology. Grasping the proximal surface, the hominid brought the distal surface down hard on an object he wished to detach or shatter, such as a bone or tuber. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The earliest known Oldowan tools date from 2.6 million years ago and were in Gona, Ethiopia. After this date, the Oldowan Industry spread throughout much of Africa. Archaeologists are currently unsure which Hominin species first developed them, with some speculating that it was Australopithecus garhi, and others saying it was Homo habilis. Homo habilis used them for a long period. About 1.9-1.8 million years ago Homo erectus inherited them. The Industry flourished in southern and eastern Africa between 2.6 and 1.7 million years ago, but also spread out of Africa and into Eurasia with homo erectus, who took Oldowan tool as far east as Java by 1.8 million years ago and Northern China by 1.6 million years ago. +

See Oldowon Tools Under TOOLS FROM THE EARLY HOMO PERIOD factsanddetails.com

hominin skull comparison

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2024