BUDDHA'S FAMILY, NAME AND BIRTHPLACE

Buddha's birth The Buddha was born about 563 B.C., though the date is a matter of some dispute, near the foothills of the Himalayas in the town of Lumbini (in present-day Nepal near the Indian border). The son of a local king, he was a Kshatriya, the Hindu caste of nobles and warriors that traced its descent to the sun. Gautama was his family name; Siddhartha, his first name. Siddhartha means "he whose goal will be accomplished". Lumbini today is a vibrant place, welcoming pilgrims and visitors from all over the world.

Siddhartha was born in Kapilavastu, a small kingdom in the Himalayan foothills. He was a prince: the son of a king of the Shakya clan (hence the name Buddha Shakyamuni, which means "sage of the Shakya clan," by which he is often referred). Siddhartha’s father Suddhodhana was the Shakya dynasty King of the kingdom of Tilaurakot. His mother’s name was Mayadevi (Maya Devi). In India, it is said, Maya Devi laid the foundations for the teachings of Buddhism. In China, she is known as Móyé Furén. Tradition holds that she died soon after giving birth to The Buddha, returning to life after seven days.

According to legend, Siddhartha’s birth was asexual. His mother dreamed that the fetus was implanted in her womb by a white elephant. Upon learning of this dream, Siddhartha’s father had the dream interpreted by a group of Brahman priests, who stated that the boy was destined to greatness, either as a great king or a religious leader. Because of the prediction of the priests, Siddhartha's father kept him confined to the palace grounds, making sure that the young boy could only experience sweetness and light and not see suffering. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

After his mother died he was brought up by Mahapajapati. She was the foster-mother, step-mother and maternal aunt (mother's sister) of the Buddha. In Buddhist tradition, she was the first woman to seek ordination in the sangha (monk community) for women, which she did from Gautama Buddha directly, and she became the first bhikkhuni (Buddhist nun). [Source: Wikipedia]

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org

See Separate Article ANCIENT INDIA IN THE TIME OF THE BUDDHA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Life of the Buddha: According to the Pali Canon” by ven Bhikkhu Ñanamoli Amazon.com ;

“Siddhartha” by Herman Hesse. Amazon.com

“Twenty Jataka Tales” (Illustrated) by Noor Inayat Khan H. Willebeek Le Mair Amazon.com ;

“Jataka Tales” (audiobook) narrated by Ellen Burstyn

Amazon.com ;

“Buddha Stories” by Demi (1997) Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Scriptures” by Donald Lopez (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“What the Buddha Taught” by Walpola Rahula Amazon.com ;

“In the Buddha's Words: Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon” with Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching” by Thich Nhat Hanh Amazon.com

Conceptions of the Buddha

According Buddhist legends both The Buddha's conception and birth were miraculous. He was conceived when his mother, Queen Maya, had dreamed that a magnificent white elephant entered her body and her right side. This was interpreted by holy men in her court as sign that she would give birth to a great king or a spiritual leader. She gave birth to him in a standing position while grasping a tree in a roadside garden.

According to a biography of The Buddha in the Jatakas: It is related that at that time the Midsummer Festival had been proclaimed in the city of Kapilavatthu, and the multitude were enjoying the feast. And queen Maha-Maya, abstaining from strong drink, and brilliant with garlands and perfumes, took part in the festivities for the six days previous to the day of full moon....And lying down on the royal couch, she fell asleep and dreamed the following dream: [Source: Translated from the Introduction to the Jataka (i.4721), Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

The four guardian angels came and lifted her up, together with her couch, and took her away to the Himalaya Mountains. There, in the Manosila table-land, which is sixty leagues in extent, they laid her under a prodigious sal-tree, seven leagues in height, and took up their positions respectfully at one side. Then came the wives of these guardian angels, and conducted her to Anotatta Lake, and bathed her, to remove every human stain. And after clothing her with divine garments, they anointed her with perfumes and decked her with divine flowers. Not far off was Silver Hill, and in it a golden mansion. There they spread a divine couch with its head towards the east, and laid her down upon it. Now the Future Buddha had become a superb white elephant, and was wandering about at no great distance, on Gold Hill. Descending thence, he ascended Silver Hill, and approaching from the north, he plucked a white lotus with his silvery trunk, and trumpeting loudly, went into the golden mansion. And three times he walked round his mother's couch, with his right side towards it, and striking her on her right side, he seemed to enter her womb. Thus the conception took place in the Midsummer Festival.

On the next day the queen awoke, and told the dream to the king. And the king caused sixty-four eminent Brahmans to be summoned, and spread costly seats for them on ground festively prepared with green leaves, Dalbergia flowers, and so forth. The Brahmans being seated, he filled gold and silver dishes with the best of milk-porridge compounded with ghee, honey, and treacle; and covering these dishes with others, made likewise of gold and silver, he gave the Brahmans to eat. And not only with food, but with other gifts, such as new garments, tawny cows, and so forth, he satisfied them completely. And when their every desire had been satisfied, he told them the dream and asked them what would come of it?

"Be not anxious, great king!" said the Brahmans; "a child has planted itself in the womb of your queen, and it is a male child and not a female. You will have a son. And he, if he continue to live the household life, will become a Universal Monarch; but if he leave the household life and retire from the world, he will become a Buddha, and roll back the clouds of sin and folly of this world."

Now the instant the Future Buddha was conceived in the womb of his mother, all the ten thousand worlds suddenly quaked, quivered, and shook. And the Thirty-two Prognostics appeared, as follows: an immeasurable light spread through ten thousand worlds: the blind recovered their sight, as if from desire to see this his glory; the deaf received their hearing; the dumb talked; the hunchbacked became straight of body; the lame recovered the power to walk; all those in bonds were freed from their bonds and chains; the fires went out in all the hells; the hunger and thirst of the Manes was stilled; wild animals lost their timidity; diseases ceased among men; all mortals became mild-spoken; horses neighed and elephants trumpeted in a manner sweet to the ear; all musical instruments gave forth their notes without being played upon; bracelets and other ornaments jingled; in all quarters of the heavens the weather became fair; a mild, cool breeze began to blow, very refreshing to men; rain fell out of season; water burst forth from the earth and flowed in streams; the birds ceased flying through the air; the rivers checked their flowing; in the mighty ocean the water became sweet; the ground became everywhere covered with lotuses of the five different colors; all flowers bloomed, both those on land and those that grow in the water; trunk-lotuses bloomed on the trunks of trees, branch-lotuses on the branches, and vine-lotuses on the vines; on the ground, stalk-lotuses, as they are called, burst through the overlying rocks and came up by sevens; in the sky were produced others, called hanging-lotuses; a shower of flowers fell all about; celestial music was heard to play in the sky; and the whole ten thousand worlds became one mass of garlands of the utmost possible magnificence, with waving chowries, and saturated with the incense-like fragrance of flowers, and resembled a bouquet of flowers sent whirling through the air, or a closely woven wreath, or a superbly decorated altar of flowers.

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Buddha's Birth

Little Buddha

According to the biographies of The Buddha, The Buddha was born fully developed in a "delightful grove, with trees of every kind, like the grove of Citraratha in Indira's Paradise" and "he did not enter the world in the usual manner, he appeared like one descending from the sky...He came out of his mother's side, without causing her pain or injury. His birth was as miraculous as that of...heroes of old who were born respectively from the thigh, from the hand, the head, or the armpit." After his birth, "with the bearing of a lion, he surveyed the four quarters, and spoke these words full of meaning for the future: 'For enlightenment I was born, for the good of all that lives. This is the last time that I have been born into this world of becoming.'" In one version the Buddha took seven steps in each cardinal direction, with lotus blossoms springing up after each step.

According to a biography of The Buddha in the Jatakas: Now other women sometimes fall short of and sometimes run over the term of ten lunar months, and then bring forth either sitting or lying down; but not so the mother of a Future Buddha. She carries the Future Buddha in her womb for just ten months, and then brings forth while standing up. This is a characteristic of the mother of a Future Buddha. So also queen Maha-Maya carried the Future Buddha in her womb, as it were oil in a vessel, for ten months; and being then far gone with child, she grew desirous of going home to her relatives, and said to king Suddhodana, [Source: Translated from the Introduction to the Jataka (i.4721), Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

"Sire, I should like to visit my kinsfolk in their city Devadaha." "So be it," said the king; and from Kapilavatthu to the city of Devadaha he had the road made even, and garnished it with plantain-trees set in pots, and with banners and streamers; and, seating the queen in a golden palanquin borne by a thousand of his courtiers, he sent her away in great pomp. Now between the two cities, and belonging to the inhabitants of both, there was a pleasure-grove of sal-trees, called Lumbini Grove. And at this particular time this grove was one mass of flowers from the ground to the topmost branches, while amongst the branches and flowers hummed swarms of bees of the five different colors, and flocks of various kinds of birds flew about warbling sweetly. Throughout the whole of Lumbini Grove the scene resembled the Cittalata Grove in Indra's paradise, or the magnificently decorated banqueting pavilion of some potent king.

When the queen beheld it she became desirous of disporting herself therein, and the courtiers therefore took her into it. And going to the foot of the monarch sal-tree of the grove, she wished to take hold of one of its branches. And the sal-tree branch, like the tip of a well-steamed reed, bent itself down within reach of the queen's hand. Then she reached out her hand, and seized hold of the branch, and immediately her pains came upon her. Thereupon the people hung a curtain about her, and retired. So her delivery took place while she was standing up, and keeping fast hold of the sal-tree branch.

At that very moment came four pure-minded Maha-Brahma angels bearing a golden net, and, receiving the Future Buddha on this golden net, they placed him before his mother and said, "Rejoice, O Queen! A mighty son has been born to you." Now other mortals on issuing from the maternal womb are smeared with disagreeable, impure matter; but not so the Future Buddha. He issued from his mother's womb like a preacher descending from his preaching-seat, or a man coming down a stair, stretching out both hands and both feet, unsmeared by any impurity from his mother's womb, and flashing pure and spotless, like a jewel thrown upon a vesture of Benares cloth. Notwithstanding this, for the sake of honoring the Future Buddha and his mother, there came two streams of water from the sky, and refreshed the Future Buddha and his mother.

See Separate Article: LUMBINI, THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE BUDDHA factsanddetails.com

For the complete article from which the material here is derived see Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

Baby Buddha

According to a biography of The Buddha in the Jatakas: Then the Brahma angels, after receiving him on their golden net, delivered him to the four guardian angels, who received him from their hands on a rug which was made of the skins of black antelopes, and was soft to the touch, being such as is used on state occasions; and the guardian angels delivered him to men who received him on a coil of fine cloth; and the men let him out of their hands on the ground, where he stood and faced the east. There, before him, lay many thousands of worlds, like a great open court; and in them, gods and men, making offerings to him of perfumes, garlands, and so on, were saying, "Great Being! There is none your equal, much less your superior." [Source: Translated from the Introduction to the Jataka (i.4721), Internet Indian History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu

When he had in this manner surveyed the four cardinal points, and the four intermediate ones, and the zenith, and the nadir, in short, all the ten directions in order, and had nowhere discovered his equal, he exclaimed, "This is the best direction," and strode forward seven paces, followed by Maha-Brahma holding over him the white umbrella, Suyama bearing the fan, and other divinities having the other symbols of royalty in their hands. Then, at the seventh stride, he halted, and with a noble voice, he shouted the shout of victory, beginning, "The chief am I in all the world."

Now in three of his existences did the Future Buddha utter words immediately on issuing from his mother's womb: namely, in his existence as Mahosadha; in his existence as Vessantara; and in this existence. As respects his existence as Mahosadha, it is related that just as he was issuing from his mother's womb, Sakka, the king of the gods, came and placed in his hand some choice sandal-wood, and departed. And he closed his fist upon it, and issued forth. "My child," said his mother, "what is it you bring with you in your hand?" "Medicine, mother," said he.

Accordingly, as he was born with medicine in his hand, they gave him the name of Osadha-Daraka [Medicine-Child]. Then they took the medicine, and placed it in an earthenware jar; and it was a sovereign remedy to heal all the blind, the deaf, and other afflicted persons who came to it. So the saying sprang up, 'This is a great medicine, this is a great medicine!" And thus he received the name of Mahosadha [Great Medicine-Man].

Birthplace of Buddha and His Predecessors

excavated buildings in Lumbini

Faxian (A.D. 337– 422 ), a Chinese Buddhist monk who traveled on foot to India, wrote in “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms": “Fifty le to the west of the city bring (the traveller) to a town named Too-wei, the birthplace of Kasyapa Buddha. At the place where he and his father met, and at that where he attained to pari-nirvana, stupas were erected. Over the entire relic of the whole body of him, the Kasyapa Tathagata, a great stupa was also erected. Going on south-east from the city of Sravasti for twelve yojanas, (the travellers) came to a town named Na-pei-kea, the birthplace of Krakuchanda Buddha. At the place where he and his father met, and at that where he attained to pari-nirvana, stupas were erected. Going north from here less than a yojana, they came to a town which had been the birthplace of Kanakamuni Buddha. At the place where he and his father met, and where he attained to pari-nirvana, stupas were erected. [Source: “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Fa-Hsien (Faxian) of his Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414), Translated James Legge, 1886, gutenberg.org/ /]

“Less than a yojana to the east from this brought them to the city of Kapilavastu (in Nepal, the places where Buddha lived until age 29); but in it there was neither king nor people. All was mound and desolation. Of inhabitants there were only some monks and a score or two of families of the common people. At the spot where stood the old palace of king Suddhodana there have been made images of the prince (his eldest son) and his mother; and at the places where that son appeared mounted on a white elephant when he entered his mother's womb, and where he turned his carriage round on seeing the sick man after he had gone out of the city by the eastern gate, stupas have been erected. The places (were also pointed out) where (the rishi) A-e inspected the marks (of Buddhaship on the body) of the heir-apparent (when an infant); where, when he was in company with Nanda and others, on the elephant being struck down and drawn to one side, he tossed it away; where he shot an arrow to the south-east, and it went a distance of thirty le, then entering the ground and making a spring to come forth, which men subsequently fashioned into a well from which travellers might drink; where, after he had attained to Wisdom, Buddha returned and saw the king, his father; where five hundred Sakyas quitted their families and did reverence to Upali while the earth shook and moved in six different ways; where Buddha preached his Law to the devas, and the four deva kings and others kept the four doors (of the hall), so that (even) the king, his father, could not enter; where Buddha sat under a nyagrodha tree, which is still standing, with his face to the east, and (his aunt) Maja-prajapati presented him with a Sanghali; and (where) king Vaidurya slew the seed of Sakya, and they all in dying became Srotapannas. A stupa was erected at this last place, which is still existing.

“Several le north-east from the city was the king's field, where the heir-apparent sat under a tree, and looked at the ploughers. Fifty le east from the city was a garden, named Lumbini, where the queen entered the pond and bathed. Having come forth from the pond on the northern bank, after (walking) twenty paces, she lifted up her hand, laid hold of a branch of a tree, and, with her face to the east, gave birth to the heir-apparent. When he fell to the ground, he (immediately) walked seven paces. Two dragon-kings (appeared) and washed his body. At the place where they did so, there was immediately formed a well, and from it, as well as from the above pond, where (the queen) bathed, the monks (even) now constantly take the water, and drink it. /

“There are four places of regular and fixed occurrence (in the history of) all Buddhas:—first, the place where they attained to perfect Wisdom (and became Buddha); second, the place where they turned the wheel of the Law; third, the place where they preached the Law, discoursed of righteousness, and discomfited (the advocates of) erroneous doctrines; and fourth, the place where they came down, after going up to the Trayatrimsas heaven to preach the Law for the benefit of their mothers. Other places in connexion with them became remarkable, according to the manifestations which were made at them at particular times. The country of Kapilavastu is a great scene of empty desolation. The inhabitants are few and far between. On the roads people have to be on their guard against white elephants and lions, and should not travel incautiously.” /

Young Gautama Siddhartha

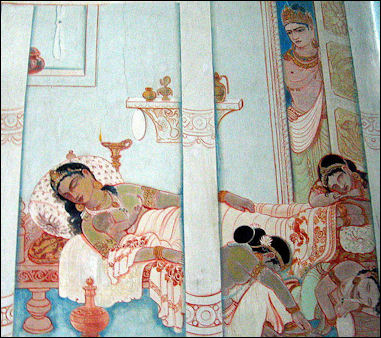

Siddhartha (Buddha) discovering sorrow

Once back in the palace, seven Brahman priests or a soothsayer --- depending on the version of the story --- told Siddhartha's father, that if the young prince stayed at home he would be the ruler of the world, but if he left he home he would become a Buddha. Siddhartha's father preferred he become the latter. To prevent him from becoming a spiritual leader, Siddhartha’s father kept him confined within palaces, providing him with luxuries and pleasures and shielding him from the harsh realities of the world. His father presumably thought that any contact with unpleasantness might prompt Siddhartha to seek a life of an ascetic. As a result Siddhartha grew up knowing nothing about the the ravages of poverty, disease, and even old age.

Siddhartha Siddhartha was a prince of Sakya, a kingdom in the fertile plains and foothills below the great Himalayas. He was brought up in luxury. During his youth he lived in three different palaces---one for winter, one for summer and one for the rainy season---where his father kept him entertained with beautiful dancing girls and musicians so that he would not be tempted to venture out into the world. Siddhartha enjoyed good health and was good at manly sports. He lived a life of luxury and didn’t leave his sumptuous palaces until he was 29.

In an early sermon, described in the the Anguttara Nikaya, the Buddha said of his childhood this way: "Bhikkhus [monks], I was delicately nurtured, exceedingly delicately nurtured, delicately nurtured beyond measure. In my father's residence lotus-ponds were made: one of blue lotuses, one of red and another of white lotuses, just for my sake.… My turban was made of Kashi cloth [silk from modern Varanasi], as was my jacket, my tunic, and my cloak.… I had three palaces: one for winter, one for summer and one for the rainy season.… In the rainy season palace, during the four months of the rains, I was entertained only by female musicians, and I did not come down from the palace". [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Siddhartha lived a typical Brahmanical life within the confines of the palace. In Hindu terms, he progressed from the student stage to the early householder stage, all while being prepared to become the future king. Siddhartha was married at the age of 16 to his cousin Yashodhara who was known as "chaste and outstanding for her beauty, modesty, and good breeding, a true Goddess of Fortune in the shape of a woman...It must be remembered that all Bodhisattvas, those beings of quite incomparable spirit, must first of all know the taste of the pleasures which the senses can give. Only then, after a son has been born to them, do they depart to the forest." His son was named Rahula.

Siddhartha Witnesses Suffering

When Siddhartha finally did venture out to see the world, with his charioteer, he came upon: 1) a diseased man, 2) a senile old man, 3) a corpse and a funeral ceremony with grieving relatives; and 4) a wandering holy man. These four encounters are known as the Four Signs and Buddhist sources say that the gods orchestrated the events. He witnesses these things on four successive chariot rides outside the palace grounds. On the fourth trip, he saw a wandering holy man whose asceticism inspired him to follow a similar path in search of freedom from the suffering caused by the infinite cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Upon witnessing death, poverty and old age for the first time, Siddhartha was shocked that such suffering could exist in the world. "This is the end," he exclaimed, "which has been fixed for all, and yet the world forgets it fears and takes no heed!...Turn back the chariot! This is no time or place for pleasure excursions. How could an intelligent person pay no heed at a time of disaster, when he knows of his impending destruction."

Afterwards, the gods sent forth a religious mendicant who told Siddhartha that it was his mission to deliver mankind from suffering. "O Bull among men," the mendicant said, "I am a recluse who, terrified by birth and death, have adopted a homeless life to win salvation! Since all that lives is to extinction doomed, salvation from this world is what I wish and so I search for that most blessed state in which extinction is unknown." The mendicant then rose into the sky like a bird. "Then and there," Buddhist scripture report, "he intuitively perceived the and made plans to leave his palace for the homeless life."

See Separate Article: BUDDHA AND THE FOUR SIGNS: HIS ENCOUNTERS WITH SUFFERING, DEATH AND OLD AGE factsanddetails.com

Siddhartha Leaves His Family

Buddha leaving his familyRealizing that pleasures are transitory and cannot prevent suffering, he put aside all his jewelry and fine clothing, Siddhartha renounced his rich upbringing and decided to become a monk. Leaving his wife and son at the palace, he embarked on a journey to seek the meaning of life and the ways in which humans can attain peace.

Because he knew his father would try to stop him, he secretly left in the middle of the night and sent all his belongings back with his servant and horse. Before setting off on his quest "to win the deathless state" he looked in on his sleeping wife and child but failed to awaken them out of fear they would try to dissuade him.

The 29-year-old Siddhartha left loved ones and life of luxury behind, accompanied only his charioteer and horse. The choice to leave his family is known as the Great Renunciation or the Great Going Forth. It represented both his break from his family and his break from the world of pleasure and desire for a quest characterizes as "baffling episodes of mysticism” that were "interrupted by blinding flashes of common sense."

Siddhartha's Wandering and Search for Enlightenment

For six years, Siddhartha pursued the teachings of the Brahmans, the Hindu priesthood. He lived as a monk, sleeping on the ground and practicing meditation to seek spiritual truth within himself. Despite fasting for extended periods of time, none of these practices helped him overcome his sorrow. Finally, the individual decided that extreme self-denial and discomfort may not lead to enlightenment, just as a life of luxury had not. Instead, they developed the 'middle way' by avoiding extremes. By rejecting both extreme pleasure and extreme pain, they believed they could find true enlightenment.[Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Siddhartha tried Hinduism, the predominant religion at that time, and the Jain faith. He studied under the erudite teachers Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputra who were reputed to have psychic powers. But their teachings did not satisfy him. He abandoned these beliefs because their followers practiced sacrifices and rituals beyond the understanding of common people. He then became an ascetic.

Siddhartha looked inward in his quest for knowledge. He went into the forest to seek the advice of holy men and to meditate. He spent six years as an ascetic, attempting to conquer the innate appetites for food, sex, and comfort by engaging in various yogic disciplines. In Siddhartha’s time, yoga was already an ancient way to seek inner knowledge and under- standing of universal truths.

Great Going Forth

Siddhartha learned from sages how to escape selfhood and enter the "sphere of neither-perception-nor-non-perception." He lived like a recluse and tried many forms of traditional asceticism. Once he meditated for so long without food that his eyes sunk so deeply into their sockets they looked like water "shining at the bottom of a deep well." During his period of asceticism, The Buddha said, "Because of so little nourishment, all my bones became like some withered creepers with knotted joints; my buttocks like a buffalo's hoof; my backbone protruding like a string of balls."

Self-punishment became a sort of pleasure in reverse, a kind of addiction that he needed to move beyond. Eventually near death from extreme fasting, he accepted a bowl of rice from a young girl. Once he had eaten, he had a realization that physical austerities were not the means to achieve spiritual liberation. Having recognized that extreme deprivation was not the way, he once again took food and followed the Middle Path (Majjhima Patipada'). He said: "This is not the Dharma which leads to dispassion, to enlightenment, to emancipation...Inward calm can not be maintained unless physical strength is constantly and intelligently replenished." When he returned to his normal diet "he gained the strength to win enlightenment."

The Buddha’s First Masters

The Buddha said: “Yes, I myself too, in the days before my full enlightenment, when I was but a bodhisattva, and not yet fully enlightened, - I too, being subject in myself to rebirth, decay and the rest of it, pursued what was no less subject thereto. But the thought came to me: -Why do I pursue what, like myself, is subject to rebirth and rest? Why, being myself subject thereto, should I not, with my eyes open to the perils which these things entail, pursue instead the consummate peace of Nirvana,-which knows neither rebirth nor decay, neither disease nor death, neither sorrow nor impurity? [Source: Translation by Lord Chalmers, Further Dialogues of the Buddha, I (London, 1926), pp. 115-18, Eliade Page +/]

“There came a time when I, being young, with a wealth of coal-black hair untouched by grey and in all the beauty of my early prime despite the wishes of my parents, who wept and lamented-cut off my hair and beard, donned the yellow robes and went forth from home to homelessness on Pilgrimage. A pilgrim now, in search of the right, and in quest of the excellent road to peace beyond compare, I came to A1ara Kalama and said — It is my wish, reverend Kalama, to lead the higher life in this your Doctrine and Rule. Stay with us, venerable sir, was his answer; my Doctrine is such that ere long an intelligent man can for himself discern, realize, enter on, and abide in, the full scope of his master's teaching. Before long, indeed very soon, I had his Doctrine by heart. So far as regards mere lip-recital and oral repetition, I could say off the (founder's) original message and the elders' exposition of it, and could profess, with others, that I knew and saw it to the full. Then it struck me that it was no Doctrine merely accepted by him on trust that Alara Ka1ama, preached, but one which he professed to have entered on and to abide in after having discerned and realized it for himself; and assuredly he had real knowledge and vision thereof. So I went to him and asked him up to what point he had for himself discerned and realized the Doctrine he had entered on and now abode in. +/

Siddhartha with the Group of Five

“Up to the plane of Naught, answered he. Hereupon, I reflected that Alara Kalama was not alone in possessing faith, perseverance, mindfulness, rapt concentration, and intellectual insight; for, all these were mine too. Why, I asked myself, should not I strive to realize the Doctrine which he claims to have entered on and to abide in after discerning and realizing it for himself? Before long, indeed very soon, I had discerned and realized his Doctrine for myself and had entered on it and abode therein. Then I went to him and asked him whether this was the point up to which he had discerned and realized for himself the Doctrine which he professed. He said yes; and I said that I had reached the same point for myself. It is a great thing, said he, a very great thing for us, that in you, reverend sir, we find such a fellow in the higher life. That same Doctrine which I for myself have discerned, realized, entered on, and profess,-that have you for yourself discerned, realized, entered on and abide in; and that same Doctrine which you have for yourself discerned, realized, entered on and profess,-that have I for myself discerned, realized, entered on, and profess. The Doctrine which I know, you too know; and the Doctrine which you know, I too know. As I am, so are you; and as you are, so am 1. Pray, sir, let us be joint wardens of this company! In such wise did Alara Kalama, being my master, set me, his pupil, on precisely the same footing as himself and show me great worship. But, as I bethought me that his Doctrine merely led to attaining the plane of Naught and not to Renunciation, passionlessness, cessation, peace, discernment, enlightenment and Nirvana,-I was not taken with his Doctrine but turned away from it to go my way. +/

“Still in search of the right, and in quest of the excellent road to peace beyond compare, I came to Uddaka Ramaputta and said;-It is my wish, reverend sir, to lead the higher life in this your Doctrine and Rule. Stay with us . . . vision thereof. So I went to Uddaka Ramaputta and asked him up to what point he had for himself discerned and realized the Doctrine he had entered on and now abode in. Up to the plane of neither perception or non-perception, answered he. +/

“Hereupon, I reflected that Uddaka Ramaputta was not alone in possessing faith . . . show me great worship. But, as I bethought me that his Doctrine merely led to attaining the plane of neither perception nor non-perception, and not to Renunciation, passionlessness, cessation, peace, discernment, enlightenment and Nirvana,-I was not taken with his Doctrine but turned away from it to go my way. +/

“Still in search of the right, and in quest of the excellent road to peace beyond compare, I came, in the course of an alms-pilgrimage through Magadha, to the Camp township at Uruveld and there took up my abode. Said I to myself on surveying the place:-Truly a delightful spot, with its goodly groves and clear flowing river with ghats and amenities, hard by a village for sustenance. What more for his striving can a young man need whose heart is set on striving? So there I sat me down, needing nothing further for my striving. +/

“Subject in myself to rebirth-decay-disease-death-sorrow-and impurity, and seeing peril in what is subject thereto, I sought after the consummate peace of Nirvana, which knows neither sorrow nor decay, neither disease nor death, neither sorrow nor impurity;-this I pursued, and this I won; and there arose within me the conviction, the insight, that now my Deliverance was assured, that this was my last birth, nor should I ever be reborn again.” +/

Buddha ans the Five Ascetics

Buddha Talks of his Ascetic Practices

'Majjhima-nikaya,'XII from the 'Maha-sihanada-sutra' reads: “Gotama Buddha is speaking to Sariputta, one of his favourite disciples. Aye, Sariputta, I have lived the fourfold higher life; I have been an ascetic of ascetics; loathly have I been, foremost in loathliness, scrupulous have I been, foremost in scrupulosity; solitary have I been, foremost in solitude. [Source: Translation by Lord Chalmers, “Further Dialogues of the Buddha,” I (London, 1926), pp. 53-7, Eliade Page website]

“(I) To such a pitch of asceticism have I gone that naked was I, flouting life's decencies, licking my hands after meals, never heeding when folk called to me to come or to stop, never accepting food brought to me before my rounds or cooked expressly for me, never accepting an invitation, never receiving food direct from pot or pan or within the threshold or among the faggots or pestles, never from (one only of) two people messing together, never from a pregnant woman or a nursing mother or a woman in coitu, never from gleanings (in time of famine) nor from where a dog is ready at hand or where (hungry) flies congregate, never touching flesh or spirits or strong drink or brews of grain. I have visited only one house a day and there taken only one morsel; or I have visited but two or (up to not more than) seven houses a day and taken at each only two or (up to not more than) seven morsels; I have lived on a single saucer of food a day, or on two, or (up to) seven saucers; I have had but one meal a day, or one every two days, or (so on, up to) every seven days, or only once a fortnight, on a rigid scale of rationing. My sole diet has been herbs gathered green, or the grain of wild millets and paddy, or snippets of hide, or water-plants, or the red powder round rice-grains within the husk, or the discarded scum of rice on the boil, or the flour of oil-seeds, or grass, or cow-dung.

“I have lived on wild roots and fruit, or on windfalls only. My raiment has been of hemp or of hempen mixture, of cerements, of rags from the dust-heap, of bark, of the black antelope's pelt either whole or split down the middle, of grass, of strips of bark or wood, of hair of men or animals woven into a blanket or of owl's wings. in fulfilment of my vows, I have plucked out the hair of my head and the hair of my beard, have never quitted the upright for the sitting posture, have squatted and never risen up, moving only a-squat, have couched on thorns, have gone down to the water punctually thrice before nightfall to wash (away the evil within). After this wise, in divers fashions, have I lived to torment and to torture my body-to such a length in asceticism have I gone.

“(ii) To such a length have I gone in loathliness that on my body I have accumulated the dirt and filth of years till it dropped off of itself-even as the rank growths of years fall away from the stump of a tinduka-tree. But never once came the thought to me to clean it off with my own.hands or to get others to clean it off for me;-to such a length in loathliness have I gone. (iii) To such a length in scrupulosity have I gone that my footsteps out and in were always attended by a mindfulness so vigilant as to awake compassion within me over even a drop of water lest I might harm tiny creatures in crevices;-to such a length have I gone in scrupulosity. (iv) To such a length have I gone as a solitary that when my abode was in the depths of the forest, the mere glimpse of a cowherd or neatherd or grasscutter, or of a man gathering firewood or edible roots in the forest, was enough to make me dart from wood to wood, from thicket to thicket, from dale to dale, and from hill to hill,-in order that they might not see me or I them. As a deer at the sight of man darts away over hill and dale, even so did I dart away at the mere glimpse of cowherd, neatherd, or what not, in order that they might not see me or I them;-to such a length have I gone as a solitary.

ascetics Sumedha and Dipankara (former incarnations of the Buddha)

“When the cowherds had driven their herds forth from the byres, up I came on all fours to find a subsistence on the droppings of the young milch-cows. So long as my own dung and urine held out, on that I have subsisted. So foul a filth-eater was I. I took up my abode in the awesome depths of the forest, depths so awesome that it was reputed that none but the passion-less could venture in without his hair standing on end. When the coil season brought chill wintry nights, then it was that, in the dark half of the months when snow was falling, I dwelt by night in the open air and in the dank thicket by day. But when there came the last broiling month of summer before the rains, I made my dwelling under the baking sun by day and in the stifling thicket by night. Then there flashed on me these verses, never till then uttered by any: Now scorched, now froze, in forest dread, alone, / naked and fireless, set upon his quest,/ the hermit battles purity to win. / In a charnel ground I lay me down with charred bones for pillow. When the cowherds' boys came along, they spat and staled upon me, pelted me with dirt and stuck bits of wood into my ears. Yet I declare that never did I let an evil mood against them arise within me.-So poised in equanimity was I.

“Some recluses and Brahmins there are who say and hold that purity cometh by way of food, and accordingly proclaim that they live exclusively on jujube-fruits, which, in one form or other, constitute their sole meat and drink. Now I can claim to have lived on a single jujube-fruit a day. If this leads you to think that this fruit was larger in those days, you would err; for, it was precisely the same size then that it is today. When I was living on a single fruit a day, my body grew emaciated in the extreme; because I ate so little, my members, great and small, grew like the knotted joints of withered creepers; like a buffalo's hoof were my shrunken buttocks; like the twists in a rope were my spinal vertebrae; like the crazy rafters of a tumble-down roof, that start askew and aslant, were my gaunt ribs; like the starry gleams on water deep down and afar in the depths of a well, shone my gleaming eyes deep down and afar in the depths of their sockets; and as the rind of a cut gourd shrinks and shrivels in the heat, so shrank and shriveled the scalp of my head,-and all because I ate so little. If I sought to feel my belly, it was my backbone which I found in my grasp; if I sought to feel my backbone, I found myself grasping my belly, so closely did my belly cleave to my backbone;-and all because I ate so little. If for ease of body I chafed my limbs, the hairs of my body fell away under my hand, rotted at their roots;-and all because I ate so little. Other recluses and Brahmins there are who, saying and holding that purity cometh by way of food, proclaim that they live exclusively on beans or sesamum rice-as their sole meat and drink. Now I can claim to have lived on a single bean a day- on a single sesamum seed a day-or a single grain of rice a day; and [the result was still the same]. Never did this practice or these courses or these dire austerities bring me to the ennobling gifts of super-human knowledge and insight. And why?-Because none of them lead to that noble understanding which, when won, leads on to Deliverance and guides him who lives up to it onward to the utter extinction of all ill.”

Buddha Becomes a Yoga Master by Practicing the Most Severe Form of Asceticism

emacited Buddha

The Buddha says in 'Majjhima-nikaya,' XXXVI in the 'Maha-saccaka-sutra': “Thought I then to myself:-Come, let me, with teeth clenched and with tongue pressed against my palate, by sheer force of mind restrain, coerce, and dominate my heart. And this I did, till the sweat streamed from my armpits. just as a strong man, taking a weaker man by the head or shoulders, restrains and coerces and dominates him, even so did 1, with teeth clenched and with tongue pressed against my palate, by sheer force of mind restrain, coerce, and dominate my heart, till the sweat streamed from my armpits. Resolute grew my perseverance which never quailed; there was established in me a mindfulness which knew no distraction,-though my body was sore distressed and afflicted, because I was harassed by these struggles as I painfully struggled on.Yet even such unpleasant feelings as then arose did not take possession of my mind. [Source: Translation by Lord ChaImers, Further Dialogues of the, Buddha, I (London, 1926), pp. 17.4-7, Eliade Page website]

“Thought I to myself: Come, let me pursue the Ecstasy that comes from not breathing. So I stopped breathing, in or out, through mouth and nose; and then great was the noise of the air as it passed through my ear-holes, like the blast from a smith's bellows. Resolute grew my perseverance . . . did not take possession of my mind. Thought I to myself: -Come, let me pursue further the Ecstasy that comes from not breathing. So I stopped breathing, in or out, through mouth and nose and ears; and then violent winds wracked my head, as though a strong man were boring into my skull with the point of a sword. Resolute grew my perseverance . . . did not take possession of my mind.

“Thought I to myself: -Come, let me pursue still further the Ecstasy that comes from not breathing. So I kept on stopping all breathing, in or out, through mouth and nose and ears; and then violent pains attacked my head, as though a strong man had twisted a leather thong round my head. Resolute grew my perseverance . . . did not take possession of my mind. Thought I to myself: -Come, let me go on pursuing the Ecstasy that comes from not breathing. So I kept on stopping breathing, in or out, through mouth and nose and ears; and then violent winds pierced my inwards through and through,-as though an expert butcher or his man were hacking my inwards with sharp cleavers. Resolute grew my perseverance . . . did not take possession of my mind.

“Thought I to myself: — Come, let me still go on pursuing the Ecstasy that comes from not breathing. So I kept on stopping all breathing, in or out, through mouth and nose and cars; and then there was a violent burning within me,-as though two strong men, taking a weaker man by both arms, were to roast and burn him up in a fiery furnace. Resolute grew my perseverance . . . did not take possession of my mind. At the sight of me, some gods said I was dead; others said I was not dead but dying; while others again said that I was an Arahat and that Arahats lived like that ! Thought I to myself: Come, let me proceed to cut off food altogether. Hereupon, gods came to me begging me not so to do, or else they would feed me through the pores with heavenly essences which would keep me alive. If, thought I to myself, while I profess to be dispensing with all food whatsoever, these gods should feed me all the time through the pores with heavenly essences which keep me alive, that would be imposture on my part. So I rejected their offers, peremptorily.

Buddha's renunciation

“Thought I to myself:-Come, let me restrict myself to little tiny morsels of food at a time, namely the liquor in which beans or vetches, peas or pulse, have been boiled. I rationed myself accordingly, and my body grew emaciated in the extreme. My members, great and small, grew like the knotted joints of withered creepers . . . (etc., as in Sutra XIII) . . . rotted at their roots; and all because I ate so little. Thought I to myself:-Of all the spasms of acute and severe pain that have been undergone through the ages past or will be undergone through the ages to come-or are now being undergone-by recluses or brahmins, mine are pre-eminent; nor is there aught worse beyond. Yet, with all these severe austerities, I fail to transcend ordinary human limits and to rise to the heights of noblest understanding and vision. Could there be another path to Enlightenment?

“A memory came to me of how once, seated in the cool shade of a rose-apple tree on the lands of my father the Shakyan, I, divested of pleasures of sense and of wrong states of mind, entered upon, and abode in, the First Ecstasy, with all its zest and satisfactions state bred of inward aloofness but not divorced from observation and reflection. Could this be the path to Enlightenment? In prompt response to this memory, my consciousness told me that here lay the true path to Enlightenment. Thought I to myself:-Am I afraid of a bliss which eschews pleasures of sense and wrong states of mind?-And my heart told me I was not afraid. Thought I to myself: -It is no easy matter to attain that bliss with a body so emaciated. Come, let me take some solid food, rice and junket; and this I ate accordingly. With me at the time there were the Five Almsmen, looking for me to announce to them what truth I attained; but when I took the rice and junket-, they left me in disgust, saying that luxuriousness had claimed me and that, abandoning the struggle, I had reverted to luxuriousness. Having thus eaten solid food and regained strength, I entered on, and abode in, the First Ecstasy.-Yet, such pleasant feelings as then arose in me did not take possession of my mind; nor did they as I successively entered on, and abode in, the Second, Third, and Fourth Ecstasies.

Faxian on Places Where Buddha Walked

Faxian (A.D. 337– 422 ), a Chinese Buddhist monk who traveled on foot to India, wrote in “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms": “From this place they travelled south-east, passing by a succession of very many monasteries, with a multitude of monks, who might be counted by myriads. After passing all these places, they came to a country named Muttra. They still followed the course of the P'oo na river, on the banks of which, left and right, there were twenty monasteries, which might contain three thousand monks; and (here) the Law of Buddha was still more flourishing. Everywhere, from the Sandy Desert, in all the countries of India, the kings had been firm believers in that Law. When they make their offerings to a community of monks they take off their royal caps, and along with their relatives and ministers, supply them with food with their own hands. That done, (the king) has a carpet spread for himself on the ground, and sits down on it in front of the chairman — they dare not presume to sit on couches in front of the community. The laws and ways according to which the kings presented their offerings when Buddha was in the world, have been handed down to the present day.

“All south from this is named the Middle Kingdom. In it the cold and heat are finely tempered, and there is neither hoarfrost nor snow. The people are numerous and happy; they have not to register their households, or attend to any magistrates and their rules; only those who cultivate the royal land have to pay (a portion of) the gain from it. If they want to go, they go; if they want to stay on, they stay. The king governs with out decapitation or (other) corporal punishments. Criminals are simply fined, lightly or heavily, according to the circumstances (of each case). Even in the cases or repeated attempts at wicked rebellion, they only have their right hands cut off. The king's body-guards and attendants all have salaries. Throughout the whole country the people do not kill any living creature, nor drink intoxicating liquor, nor eat onions or garlic. The only exception is that of the Chandalas. That is the name for those who are (held to be) wicked men, and live apart from others. When they enter the gate of a city or a market-place, they strike a piece of wood to make themselves known, so that men know and avoid them, and do not come into contact with them. In that country they do not keep pigs and fowls, and do not sell live cattle; in the markets there are no butchers' shops and no dealers in intoxicating drink....Only the Chandalas a fishermen and hunters, and sell flesh meat.

At the places where Buddha, when he was in the world, cut his hair and nails, topes are erected and where the three Buddhas that preceded Sakyamuni Buddha and he himself sat; where they walked, and where images of their persons were made. At all these places topes were made, and are still existing. At the place where Sakra, Ruler of the Devas, and the king of the Brahmaloka followed Buddha down (from the Trayastrimsas heaven) they have also raised a tope. At this place the monks and nuns may be a thousand, who all receive their food from the common store, and pursue their studies, some of the mahayana and some of the hinayana. Where they live, there is a white-eared dragon, which acts the part of patron to the community of these monks, causing abundant harvests in the counry, and the enriching rains to come in season, without the occurrence of any calamities, so that the monks enjoy their repose and ease. In gratitude for its kindness, they have made for it a dragon-house, with a carpet for it to sit on, and appointed for it a diet of blessing, which they present for its nourishment. Every day they set apart three of their number to go to its house, and eat there. Whenever the summer retreat is ended, the dragon straightway changes its form, and appears as a small snake, with white spots at the side of its ears. As soon as thee monks recognise it, they fill a copper vessel with cream, into which they put the creature, and then carry it around from the one who has the highest seat (at their tables) to him who has the lowest, when it appears as if saluting them. When it has been taken round, immediately it disappears; and every year it thus comes forth once. The country is very productive, and the people are prosperous and happy beyond comparison. When people of other countries come to it, they are exceedingly attentive to them all, and supply them with what they need.

baby Buddha Taking a Bath, Gandhara, AD 2ndCentury

Places Associated with Buddha's Daily Life

Faxian wrote: “At the places where Buddha, when he was in the world, cut his hair and nails, stupas are erected; and where the three Buddhas that preceded Sakyamuni Buddha and he himself sat; where they walked, and where images of their persons were made. At all these places stupas were made, and are still existing. At the place where Sakra, Ruler of the Devas, and the king of the Brahma-loka followed Buddha down (from the Trayastrimsas heaven) they have also raised a stupa. [Source: “A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms” by Fa-Hsien (Faxian) of his Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414), Translated James Legge, 1886, gutenberg.org/ /]

“At this place the monks and nuns may be a thousand, who all receive their food from the common store, and pursue their studies, some of the mahayana and some of the hinayana. Where they live, there is a white-eared dragon, which acts the part of danapati to the community of these monks, causing abundant harvests in the country, and the enriching rains to come in season, without the occurrence of any calamities, so that the monks enjoy their repose and ease. In gratitude for its kindness, they have made for it a dragon-house, with a carpet for it to sit on, and appointed for it a diet of blessing, which they present for its nourishment. Every day they set apart three of their number to go to its house, and eat there. Whenever the summer retreat is ended, the dragon straightway changes its form, and appears as a small snake, with white spots at the side of its ears. As soon as the monks recognise it, they fill a copper vessel with cream, into which they put the creature, and then carry it round from the one who has the highest seat (at their tables) to him who has the lowest, when it appears as if saluting them. When it has been taken round, immediately it disappeared; and every year it thus comes forth once. The country is very productive, and the people are prosperous, and happy beyond comparison. When people of other countries come to it, they are exceedingly attentive to them all, and supply them with what they need. /

“Fifty yojanas north-west from the monastery there is another, called "The Great Heap." Great Heap was the name of a wicked demon, who was converted by Buddha, and men subsequently at this place reared a vihara. When it was being made over to an Arhat by pouring water on his hands, some drops fell on the ground. They are still on the spot, and however they may be brushed away and removed, they continue to be visible, and cannot be made to disappear. /

“At this place there is also a stupa to Buddha, where a good spirit constantly keeps (all about it) swept and watered, without any labour of man being required. A king of corrupt views once said, "Since you are able to do this, I will lead a multitude of troops and reside there till the dirt and filth has increased and accumulated, and (see) whether you can cleanse it away or not." The spirit thereupon raised a great wind, which blew (the filth away), and made the place pure. /

“At this place there are a hundred small stupas, at which a man may keep counting a whole day without being able to know (their exact number). If he be firmly bent on knowing it, he will place a man by the side of each stupa. When this is done, proceeding to count the number of men, whether they be many or few, he will not get to know (the number). There is a monastery, containing perhaps 600 or 700 monks, in which there is a place where a Pratyeka Buddha used to take his food. The nirvana ground (where he was burned after death) is as large as a carriage wheel; and while grass grows all around, on this spot there is none. The ground also where he dried his clothes produces no grass, but the impression of them, where they lay on it, continues to the present day.” /

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024