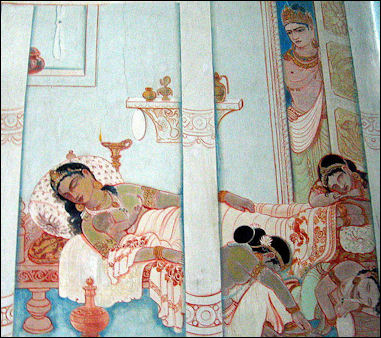

SIDDHARTHA WITNESSES SUFFERING

Siddhartha (Buddha) discovering sorrow

The Buddha — Siddhartha Gautama — was born about 563 B.C., though the date is a matter of some dispute, near the foothills of the Himalayas in the town of Lumbini (in present-day Nepal near the Indian border). The son of a local king, he was a Kshatriya, the Hindu caste of nobles and warriors that traced its descent to the sun. In the early years of his life he never ventured outside the palace where he lived.

One day Siddhartha persuaded his chariot driver to take him outside of the palace, and there he saw four things that would transform his life: 1) a diseased man, 2) a senile old man, 3) a corpse and a funeral ceremony with grieving relatives; and 4) a wandering holy man. These four encounters are known as the Four Signs and Buddhist sources say that the gods orchestrated the events. He witnesses these things on four successive chariot rides outside the palace grounds. [Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

Upon seeing an old man on his first trip outside the place, Siddhartha asked his driver, "Good charioteer, who is this man with white hair, supporting himself on the staff in his hand, with his eyes veiled by the brows, and limbs relaxed and bent? Is this some transformation in him, or his original state, or mere chance?" The driver answered that it was old age, and the prince asked, "Will this evil come upon me also?" The answer was, of course, "Yes." [Source: Jacob Kinnard,Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Siddhartha's experiences with suffering (duhkha; Pali, dukkha) transformed the once happy prince into a brooding young man. As one text puts it, "He was perturbed in his lofty soul at hearing of old age, like a bull on hearing the crash of a thunderbolt nearby." Siddhartha wondered if perhaps this luxurious palace life was not reality but instead was an illusion of some sort, and he thenceforth wandered around in a profound existential crisis. "This is the end," he exclaimed, "which has been fixed for all, and yet the world forgets it fears and takes no heed!...Turn back the chariot! This is no time or place for pleasure excursions. How could an intelligent person pay no heed at a time of disaster, when he knows of his impending destruction."

On the fourth trip, Siddhartha saw a wandering holy man. This encounter provided a potential way out of the realm of suffering. The asceticism pf the holy man inspired Siddhartha to follow a similar path in search of freedom from the suffering caused by the infinite cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. Siddhartha resolved to leave the palace and go out into the world and wander in search of the truth. Afterwards, the gods sent forth a religious mendicant who told Siddhartha that it was his mission to deliver mankind from suffering. "O Bull among men," the mendicant said, "I am a recluse who, terrified by birth and death, have adopted a homeless life to win salvation! Since all that lives is to extinction doomed, salvation from this world is what I wish and so I search for that most blessed state in which extinction is unknown." The mendicant then rose into the sky like a bird.

"Then and there," Buddhist scripture report, "he intuitively perceived the and made plans to leave his palace for the homeless life." He then sneaked out in the middle of the night after first going to his sleeping father to explain that he was not leaving out of lack of respect nor out of selfishness but because he had a profound desire to liberate the world from old age, death, the fear of suffering that comes with old age and death and free the world of suffering.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org

Siddhartha Encounters Old Age

According to to 'Digha-nikaya,' XIV of 'Mahapadana suttanta': “Now the young lord Gotama, when many days had passed by, bade his charioteer make ready the state carriages, saying: 'Get ready the carriages, good charioteer, and let us go through the park to inspect the pleasaunce.' 'Yes, my lord,' replied the charioteer, and harnessed the state carriages and sent word to Gotama: 'The carriages are ready, my lord; do now what you deem fit.' Then Gotama mounted a state carriage and drove out in state into the park. [Source: From Clarence H. Hamilton, Buddhism (New York, 1952), pp. 6-11, quoting translation by E. H. Brewster, in his Life of Gotama the Buddha, pp. 15-19. See also Rhys Davids, Dialogues of the Buddha, part 2 (Oxford, 1910), pp. 18 ff., which follows Brewster's translation closely, Eliade Page website]

“Now the young lord saw, as he was driving to the park, an aged man as bent as a roof gable, decrepit, leaning on a staff, tottering as he walked, afflicted and long past his prime. And seeing him Gotama said: 'That man, good charioteer, what has he done, that his hair is not like that of other men, nor his body?' 'He is what is called an aged man, my lord.' 'But why is he called aged?' 'He is called aged, my lord, because he has not much longer to live.' 'But then, good charioteer, am I too subject to old age, one who has not got past old age?'

'You, my lord, and we too, we all are of a kind to grow old; we have not got past old age.' 'Why then, good charioteer., enough of the park for today. Drive me back hence to my rooms.' 'Yea, my lord,' answered the charioteer, and drove him back. And he, going to his rooms, sat brooding sorrowful and depressed, thinking, 'Shame then verily be upon this thing called birth, since to one born old age shows itself like that !'

Thereupon the raja sent for the charioteer and asked him: 'Well, good charioteer, did the boy take pleasure in the park? Was he pleased with it?' 'No, my lord, he was not.' 'What then did he see on his drive?' (And the charioteer told the raja all.) Then the raja thought thus: We must not have Gotama declining to rule. We must not have him going forth from the house into the homeless state. We must not let what the brahman soothsayers spoke of come true. So, that these things might not come to pass, he let the youth be still more surrounded by sensuous pleasures. And thus Gotama continued to live amidst the pleasures of sense.”

Siddhartha Encounters Sickness

According to to 'Digha-nikaya,' XIV of 'Mahapadana suttanta': “Now after many days had passed by, the young lord again bade his charioteer make ready and drove forth as once before...And Gotama saw, as he was driving to the park, a sick man, suffering and very ill, fallen and weltering in his own water, by some being lifted up, by others being dressed. Seeing this, Gotama asked: 'That man, good charioteer, what has he done that his eyes are not like others' eyes, nor his voice like the voice of other men?' 'He is what is called ill, my lord.' [Source: From Clarence H. Hamilton, Buddhism (New York, 1952), pp. 6-11, Eliade Page website]

'But what is meant by ill?' 'It means, my lord, that he will hardly recover from his illness.' 'But I am too, then, good charioteer, subject to fall ill; have I not got out of reach of illness?' 'you, my lord, and we too, we are all subject to fall ill; we have not got beyond the reach of illness.' 'Why then, good charioteer, enough of the park for today. Drive me back hence to my rooms. 'Yea, my lord,' answered the charioteer, and drove him back. And he, going to his rooms, sat brooding sorrowful and depressed, thinking: Shame then verily be upon this thing called birth, since to one born decay shows itself like that, disease shows itself like that.

Thereupon the raja sent for the charioteer and asked him: 'Well, good charioteer, did the young lord take pleasure in the park and was he pleased with it?' 'No, my lord, he was not.' 'What did he see then on his drive?' (And the charioteer told the raja all.) Then the raja thought thus: We must not have Gotama declining to rule; we must not have him going forth from the house to the homeless state; we must not let what the brahman soothsayers spoke of come true. So, that these things might not come to pass, he let the young man be still more abundantly surrounded by sensuous pleasures. And thus Gotama continued to live amidst the pleasures of sense.”

Siddhartha Encounters Death

According to to 'Digha-nikaya,' XIV of 'Mahapadana suttanta': “Now once again, after many days the young lord Gotama . . . drove forth. And he saw, as he was driving to the park, a great concourse of people clad in garments of different colours constructing a funeral pyre. And seeing this he asked his charioteer: 'Why now are all those people come together in garments of different colours, and making that pile?' 'It is because someone, my lord, has ended his days.' 'Then drive the carriage close to him who has ended his days.' 'Yea, my lord,' answered the charioteer, and did so. And Gotama saw the corpse of him who had ended his days and asked: 'What, good charioteer, is ending one's days?' [Source: From Clarence H. Hamilton, Buddhism (New York, 1952), pp. 6-11, Eliade Page website]

'It means, my lord, that neither mother, nor father, nor other kinsfolk will now see him, nor will he see them.' 'But am I too then subject to death, have I not got beyond reach of death? Will neither the raja, nor the ranee, nor any other of my kin see me more, or shall I again see them?' 'You, my lord, and we too, we are all subject to death; we have not passed beyond the reach of death. Neither the raja, nor the ranee, nor any other of your kin will see you any more, nor will you see them.' 'Why then, good charioteer, enough of the park for today. Drive me back hence to my rooms.' 'Yea, my lord,' replied the charioteer, and drove him back.

And he, going to his rooms, sat brooding sorrowful and depressed, thinking: Shame verily be upon this thing called birth, since to one born the decay of life, since disease, since death shows itself like that I Thereupon the raja Questioned the charioteer as before and as before let Gotama be still more surrounded by sensuous enjoyment. And thus he continued to live amidst the_ pleasures of sense.

Siddhartha Encounters a Holy Man

According to to 'Digha-nikaya,' XIV of 'Mahapadana suttanta': Now once again, after many days . . . the lord Gotama . . . drove forth. And he saw, as he was driving to the park, a shaven-headed man, a recluse, wearing the yellow robe. And seeing him he asked the charioteer, 'That man, good charioteer, what has he done that his head is unlike other men's heads and his clothes too are unlike those of others?' 'That is what they call a recluse, because, my lord, he is one who has gone forth.' [Source: From Clarence H. Hamilton, Buddhism (New York, 1952), pp. 6-11, Eliade Page website]

'What is that, "to have gone forth"?' 'To have gone forth, my lord, means being thorough in the religious life, thorough in the peaceful life, thorough in good action, thorough in meritorious conduct, thorough in harmlessness, thorough in kindness to all creatures.' 'Excellent indeed, friend charioteer, is what they call a recluse, since so thorough in his conduct in all those respects, wherefore drive me up to that forthgone man.' 'Yea, my lord,' replied the charioteer and drove up to the recluse. Then Gotama addressed him, saying, 'You master, what have you done that your head is not as other men's heads, nor your clothes as those of other men?'

'I, my lord, am one whose has gone forth.' 'What, master, does that mean?' 'It means, my lord, being thorough in the religious life, thorough in the peaceful life, thorough in good actions, thorough in meritorious conduct, thorough in harmlessness, thorough in kindness to all creatures.' 'Excellently indeed, master, are you said to have gone forth since so thorough is your conduct in all those respects.' Then the lord Gotama bade his charioteer, saying: 'Come then, good charioteer, do you take the carriage and drive it back hence to my rooms. But I will even here cut off my hair, and don the yellow robe, and go forth from the house into the homeless state.' 'Yea, my lord,' replied the charioteer, and drove back. But the prince Gotama,. there and then cutting off his hair and donning the yellow robe, went forth from the house into the homeless state.

Now at Kapilavatthu, the raja's seat, a great number of persons, some eighty-four thousand souls, heard of what prince Gotama had done and thought: Surely this is no ordinary religious rule, this is no common going forth, in that prince Gotama himself has had his head shaved and has donned the yellow robe and has gone forth from the house into the homeless state. If prince Gotama has done this, why then should not we also? And they all had their heads shaved and donned the yellow robes, and in imitation of the Bodhisat they went forth from the house into the homeless state. So the Bodhisat went up on his rounds through the villages, towns and cities accompanied by that multitude.

Now there arose in the mind of Gotama the Bodhisat, when he was meditating in seclusion, this thought: That indeed is not suitable for me that I should live beset. 'Twere better were I to dwell alone, far from the crowd. So after a time he dwelt alone, away from the crowd. Those eightyfour thousand recluses went one way, and the Bodhisat went another way. Now there arose in the mind of Gotama the Bodhisat, when he had gone to his place and was meditating in seclusion, this thought: Verily, this world has fallen upon trouble-one is born, and grows old, and dies, and falls from one state, and springs up in another. And from the suffering, moreover, no one knows of any way of escape, even from decay and death. 0, when shall a way of escape from this suffering be made known-from decay and from death?'

Siddhartha Leaves His Family

Buddha leaving his familyRealizing that pleasures are transitory and cannot prevent suffering, he put aside all his jewelry and fine clothing, Siddhartha renounced his rich upbringing and decided to become a monk. Leaving his wife and son at the palace, he embarked on a journey to seek the meaning of life and the ways in which humans can attain peace.

Because he knew his father would try to stop him, he secretly left in the middle of the night and sent all his belongings back with his servant and horse. Before setting off on his quest "to win the deathless state" he looked in on his sleeping wife and child but failed to awaken them out of fear they would try to dissuade him.

The 29-year-old Siddhartha left loved ones and life of luxury behind, accompanied only his charioteer and horse. The choice to leave his family is known as the Great Renunciation or the Great Going Forth. It represented both his break from his family and his break from the world of pleasure and desire for a quest characterizes as "baffling episodes of mysticism” that were "interrupted by blinding flashes of common sense."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024