GNOSTICISM

Gnostics were Christian mystics who emerged between around A.D. 100 in Egypt and christianized a pagan sun festival around A.D. 120-140. Influenced by Plato and other Greek philosophers, they viewed things in dualistic terms such as between the goodness of the spirit and the evil of the earth and between a real world and false world. Gnosticism may have originally been a Christian adaption of the Greek philosophy. “ Gnosis”is the Greek word for knowledge. Much of what we know about the Gnostics comes from the Nag Hammadi manuscripts.

Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe of Kings College London wrote for the BBC:““Gnosticism is derived from the Greek word gnosis, which means ‘knowledge’, and expresses the fact that adherents of Gnosticism believed that they had privileged access to hidden knowledge about the divine. The Gnostics believed themselves to be chosen ones, with particles of the divinity trapped in the matter of their bodies. These divine sparks could, with special knowledge and practices, be freed to rejoin their celestial home. Gnostic elitism was one of the things which antagonised those Christians who believed their Gospel to have been preached to all, not to a select group. The Gnostic belief that matter and creation was evil was also vigorously combated by Christians who saw this as an affront to the intentions of their good creator God. [Source: Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Carl A. Volz wrote: Gnosticism was a complex religious movement which in its Christian form comes into clear prominence in the 2nd century. It is now generally held that Christian gnosticism had its origins in trends of thought already present in pagan religious circles. In Christianity, the movement appeared at first as a school (or schools) of thought within the Church; it soon established itself in all the principal centers of Christianity; and by the end of the 2nd century the gnostics had mostly become separate sects. In some of the later books of the NT (e.g. I John and Pastorals) forms of false teaching are denounced which appear to be similar to, though less developed than, the gnostic systems of teaching of 2nd C. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

See Separate Article GNOSTIC BELIEFS AND TEXTS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Gnostic Gospels” by Elaine Pagels, Lorna Raver, et al. Amazon.com awarded a National Book Award and was a surprise bestseller;

“The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts” by Marvin W. Meyer, Elaine H. Pagels, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gnostics” by Jacques Lacarriere Amazon.com ;

“Lost Christianities: The Battles of Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew”

by Bart D. Ehrman, Matthew Kugler, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gospel According to Heretics: Discovering Orthodoxy through Early Christological Conflicts” by David E. Wilhite Amazon.com ;

“The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church — and How It Died” by Philip Jenkins, Dick Hill, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian Controversy: The Making of a Saint and of a Heretic” by Susan Wessel Amazon.com ;

“Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity” by Otto F.A. Meinardus Amazon.com ;

“The History of the Coptic Church After Chalcedon (451-1300)” by Bishop Youanis Amazon.com ;

“Coptic Monasteries: Egypt's Monastic Art and Architecture” by Gawdat Gabra and Tim Vivian Amazon.com ;

“Backgrounds of Early Christianity” by Everett Ferguson Amazon.com ;

“After Jesus, Before Christianity: A Historical Exploration of the First Two Centuries of Jesus Movements” by Erin Vearncombe, Brandon Scott, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Gnostics

Candida Moss wrote in the Daily Beast: According to Christian tradition, Gnostics believed that the material world was created by an inferior and malicious deity, that gnosis (‘knowledge’) would help enlighten Christians to escape this world and return to the real transcendent deity, that suffering and martyrdom should be avoided, and that the body was useless and irrelevant. Recent scholarship has questioned the accuracy of this caricature and suggested instead that the Gnostics were philosophically inclined Christians who were in many ways identical to their more orthodox counterparts (others have questioned if Gnostics existed at all as an identifiable group and argue that the term is just a polemical invention). [Source: Candida Moss, Daily Beast, December 10, 2017]

Gnostic Bardesan

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “Many, many Christians, who are not appreciated by many of the leaders of the church, believed that spiritual awakening was demonstrated in one's capacity to speak in either revelation or dream visions.... Such Christians often spoke in poems, in songs, in stories that we would say come out of the creative imagination or the religious imagination. Fathers of the church objected and said, "Well, they're just making up a lot of garbage. It's a ridiculous thing that they are just inventing themselves out of their own feelings." But as they saw it, the sense of an original voice, an original insight, is as we would see it, say, in a creative writing class today, was evidence that that person has discovered his or her genuine voice. [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Did the gnostics see themselves as being outside? “The people who wrote and circulated gospels like the Gospel of Thomas certainly didn't think they were heretics. They thought of themselves as Christians who had received, in addition to the other gospels, secret teaching. For example in the 4th chapter of the Gospel of Mark, Mark says that Jesus taught certain things privately to the disciples. And Paul too says that he had secret teaching. And these claim to give some of the secret teaching of Jesus. Whether he actually did teach secretly or not, we don't know otherwise. But the Gospel of Thomas claims to be this kind of secret teaching.

“A spokesman for the orthodox church called certain other Christians gnostics. We don't know quite what they mean by that except that they didn't like their viewpoints. The people whom they called gnostics would have called themselves Christian. And they were Christians of very diverse viewpoints. I mean, we think today Christianity looks diverse. If you look from Pentecostal churches to Roman Catholic Churches, to orthodox churches, to every kind of Protestant Church one can imagine, we think that's diversity. But actually most Christians today share a common list of New Testament writings, they share a certain kind of structure of church, and a certain core of beliefs. But back then there was no list of agreed gospels. There was no list of agreed doctrines. And there was no agreed upon structure. So actually the early Christian movement was much more wildly diverse. And perhaps that's why that part of the movement in fact couldn't survive.

Different Gnostic Groups

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “The term gnosticism is often used as a sort of umbrella term to cover the people that the leaders of the church don't like. It covers probably a huge variety of points of view. And yet there is a theme; the way I connect text that we think of as gnostic is the sense that the divine is to be discovered by some kind of interior search, and not simply by a savior who is outside of you. [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe of Kings College London wrote for the BBC:“'Gnosticism' is a vague term which encompasses sects closely associated with Christianity and much larger movements contemporary with, but unrelated to, Christianity. “These different Gnostic groups all had widely divergent views. Much as there were many 'Christianities' in the first few centuries AD, there were many Gnosticisms, including such famous sects as Manicheism. “Different Gnostic groups were influenced by Jewish and Christian doctrine, as well as by Platonic philosophy, but they shared some essential beliefs. [Source: Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, BBC, February 17, 2011 |::|]

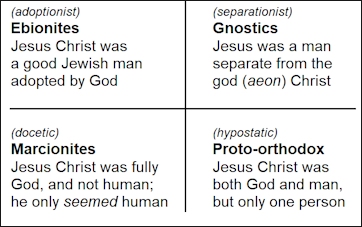

Jean-Pierre Isbouts wrote in National Geographic History: Some sects adhered to the belief that deep meditation and immersion in the divine would ultimately lead to a secret knowledge of God. That idea was popular, for it agreed with the premise in Greek philosophy that each human being carries inside a spark of the divine. For Gnostic Christians, that also explained why Jesus often spoke in parables. True knowledge of God was a precious and potentially dangerous secret that could be revealed only to those who proved themselves wor-thy of that knowledge. Some sects, such as the Docetists, believed Jesus’ physical presence had been an illusion — that he had always been a divine being. Another sect, led by a wealthy individual named Marcion (ca A.D. 85–160), son of the bishop of Sinope (today’s Sinop in Turkey), believed that Christianity should be uncoupled from Jewish influence and be made into a more purely Gentile religion. The Ebionite sect held true to its Jewish roots, in maintaining that Jesus had always been a mere mortal. [Source: Jean-Pierre Isbouts, National Geographic History, December 1, 2022]

Carl A. Volz wrote: “Gnosticism took many different forms, commonly associated with the names of particular teachers, e.g. Valentinus and Basilides. A central importance was attached to gnosist the supposedly revealed knowledge of God and of the origin and destiny of mankind, by means of which the spiritual element in man could receive redemption. The source of this special gnosis was held to be either the Apostles, from whom it was derived by a secret tradition, or a direct revelation given to the founder of the sect. The systems of teaching range from those which embody much genuine philosophical speculation to those which are wild amalgams of mythology and magical rites drawn from all quarters, with the most slender admixture of Christian elements. The Old Testament books were used and expounded, together with many of the New Testament books, and a central place was assigned to the figure of Jesus, but on a number of fundamental points the interpretation of these features differed widely from that of orthodox Christianity.” [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

Impact of the Gnostics on Christianity

Gnostic views were a little too bizarre and mystical for most Christians. As a reaction to them, the Christian majority adopted a more down to earth and flesh and blood conception of Jesus and Christianity. Ultimately Gnostics were condemned as heretics by the early Christian church and later by the Catholics. In A.D. 367, Archbishop Athanasius of Alexandria, provider of the first list of the 27 books that would ultimately become the New Testament, called the Gnostic texts “illegitimate and secret.” The 2nd century heresy hunter, Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons, said these works of “so-called gnosos” were “full of blasphemy.”

Why were the Gnostics received with such hostility? Princeton Biblical scholar Elaine Page has suggested that it was because they undermined the underlying basis for church structure: the belief that Jesus bestowed ecclesiastical authority only on the male apostles who saw him after his resurrection, thereby establishing the one of succession running from his inner circle of disciples.

Many people with a fascination with mysticism, New Age spiritualism, and eastern philosophy and religion have taken an interest in Gnosticism. One American-born Zen priest jokingly told Time, “Had I know the “Gospel of Thomas”, I wouldn’t have become a Buddhist.” The Gnostic view that world is a place of suffering is similar to the view that Buddhists have.

The premise of the Matrix series of films — that the world we live in an illusion created by an evil power — comes from the Gnostics. At one point in the film Morphepus tells Neo, “The Matrix is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.”

Development of Gnosticism

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “Gnosticism is a term that's etymologically connected with the word "to know." It has the same root in English, "kno" is related to "gno" the Greek word for gnosis. And Gnostics were people who claimed to know something special. This knowledge could be a knowledge of a person, the kind of personal acquaintance that a mystic would have with the divine. Or it could be a kind of propositional knowledge of certain key truths. Gnostics claim both of those kinds of knowledge. The claim to have some sort of special knowledge was not confined to any particular group in the second century. It was widespread, and we have such claims being advanced by fairly orthodox teachers such as Clement of Alexandria, we have similar claims being advanced by all sorts of other teachers during that period. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“It's difficult to know with precision how gnosticism emerged. Because the way we use the term today is as a cover for a variety of phenomena during the course of the second century. One main strand of gnosticism seems to have emerged as a way of reflecting on Jewish scripture and reflecting on Jewish traditions about the descent of the angels to beget children by human beings. Using that old tradition as a way of reflecting on why there's evil in the world. So in one way, gnosticism is a movement that has a philosophical or a theological dimension that's wrestling with the problem of theodicy. And many gnostics solve that problem by saying there's a sharp dichotomy between the world of matter and the world of spirit, and they're very much interested in getting into the world of spirit, removing themselves from the world of matter. They explain that dichotomy with elaborate theories about how spirit got involved with matter and then with practices, usually ascetical practices, to enable spirit to return to its own place.

Myth of Origins, Non-Canon Heretics and Gnostics

Coptic bust

Karen King at Harvard Divinity School is a critic of what she calls the “master story” of Christianity: a narrative that casts the New Testament as divine revelation that passed through Jesus in “an unbroken chain” to the apostles and their successors—church fathers, ministers, priests and bishops who carried its truths into the present day. Owen Jarus wrote in Live Science: According to this “myth of origins,” as she has called it, followers of Jesus who accepted the New Testament canon—chiefly the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, written roughly between A.D. 65 and A.D. 95, or at least 35 years after Jesus’ death—were true Christians. Followers inspired by noncanonical gospels were heretics hornswoggled by the devil. [Source: Owen Jarus, Live Science, October 5, 2015 /~/]

“Until the last century, virtually everything scholars knew about these other gospels came from broadsides against them by early Church leaders. Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyon, France, pilloried them in A.D. 180 as “an abyss of madness and of blasphemy”—a “wicked art” practiced by people bent on “adapting the oracles of the Lord to their opinions.” A challenge to Christianity’s master story surfaced in December 1945, when an Arab farmer digging near the town of Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt, stumbled on a cache of manuscripts. Inside a meter-tall clay jar containing 13 leatherbound papyrus codices were 52 texts that didn’t make it into the canon, including the gospel of Thomas, the gospel of Philip and the Secret Revelation of John. /~/

“As scholars translated the texts from Coptic, early Christians whose views had fallen out of favor—or were silenced—began speaking again, across the ages, in their own voices. A picture began to take shape of long-ago Christians, scattered across the Eastern Mediterranean, who derived sometimes contradictory teachings from the life of Jesus Christ. Was it possible that Judas was not a turncoat but a favored disciple? Did Christ’s body really rise, or just his soul? Was the crucifixion—and human suffering, more broadly—a prerequisite for salvation? /~/

“Only later did an organized Church sort the answers to those questions into the categories of orthodoxy and heresy. (Some scholars prefer the term “Gnostic” to heretical; King rejects both, arguing in a 2003 book that “Gnosticism” is a construct “invented in the early modern period to aid in defining the boundaries of normative Christianity.”)” /~/

"Heretics" Defined in Response to Persecution

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “As far as we can tell, the earliest Christian communities had an enormous variety of viewpoints and attitudes and approach, as we've said. But by the end of the second century, you begin to see hierarchies of bishops, priests and deacons emerge in various communities and claim to speak for the majority. And with that development, there's probably an assertion of leadership against viewpoints that those leaders considered dangerous and heretical. One of the issues that polarized those communities, perhaps the most urgent and pressing issue, was persecution. That is, these people, all Christians, belonged to an illegal movement. It was dangerous to belong to this movement. You could be arrested, if you were charged with being a Christian, you could be put on trial, you could be tortured and executed if you refused to recant. And with that pressure, many said, "We want to know when a person joins this movement if that person is going to stand with us or is going to pretend they're not with us. So let's clarify who belongs to us...." [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998]

Lion-faced diety from a Gnostic text

“The Bishop Irenaeus was about 18 to 20 years old when his little community was absolutely decimated by a devastating persecution. They say that 50 to 70 people in two small towns were tortured and executed. That must have meant hundreds were rounded up and put in prison. But 50 to 70 people in two small towns executed in public is a devastating destruction of that beleaguered community. And Irenaeus was trying to unify those who were left. What frustrating him is that they didn't all believe the same thing. They didn't all gather under one kind of leadership. And he, like others, was deeply aware of the dangers of fragmentation, that one community could be lost. And so it is out of that deep concern, I think, that Irenaeus and others began to try to unify the church, and, and create criteria like, you know, these are the four gospels. These are what we believe, these are the rituals, which you first do. You're baptized and then you're a member of this community. It would be absurd to suggest that the leaders of the church were out to protect their power.

“Because to become bishop in a church in which the 92 year old bishop had just died in prison, which is what Irenaeus did as a very young man, he had the courage to become bishop, is to become a target for the next persecution. This is not a position of power, it's a position of danger and courage. And those people were concerned to try to unify the church. So it would be ridiculous to tell the story of the early Christian movement as though the orthodox were, you know, power mad, and trying to destroy all diversity in the church. It's much more complicated than that. The sociologist Max Weber has shown that a religious movement, if it doesn't develop a certain institutional structure within a generation of its founder's death, will not survive. So it's likely, I think, that we owe the survival of the Christian movement to those forms that Irenaeus and others developed. You know, the list of acceptable books, the list of acceptable teachings, the rituals.”

Irenaeus on Gnostic Heretical Views of Jesus

St.Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130-202) is considered the father of heresy. In Irenaeus Against Heresies Worship in Spirit and in Truth he discusses the Gnostic Version of Jesus' "In Spirit and in Truth Concept.". Adversus haereses (inter A.D. 180/199), Book I, Chapter 1 goes: Absurd ideas of the disciples of Valentinus as to the origin, name, order, and conjugal productions of their fancied aeons, with the passages of Scripture which they adapt to their opinions. [Source: Translated by the Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson. Excerpted from Volume I of The Ante-Nicene Fathers (Rev. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, editors); American Edition copyright 1885]

1) They maintain, then, that in the invisible and ineffable heights above there exists a certain perfect, pre-existent Aeon, whom they call Proarche, Propator, and Bythus, and describe as being invisible and incomprehensible. Eternal and unbegotten, he remained throughout innumerable cycles of ages in profound serenity and quiescence. There existed along with him Ennoea, whom they also call Charis and Sige. At last this Bythus determined to send forth from himself the beginning of all things, and deposited this production (which he had resolved to bring forth) in his contemporary Sige, even as seed is deposited in the womb. She then, having received this seed, and becoming pregnant, gave birth to Nous, who was both similar and equal to him who had produced him, and was alone capable of comprehending his father's greatness.

St.Irenaeus of Lyons

This Nous they call also Monogenes, and Father, and the Beginning of all Things. Along with him was also produced Aletheia; and these four constituted the first and first-begotten Pythagorean Tetrad, which they also denominate the root of all things. For there are first Bythus and Sige, and then Nous and Aletheia. And Monogenes, perceiving for what purpose he had been produced, also himself sent forth Logos and Zoe, being the father of all those who were to come after him, and the beginning and fashioning of the entire Pleroma. By the conjunction of Logos and Zoo were brought forth Anthropos and Ecclesia; and thus was formed the first-begotten Ogdoad, the root and substance of all things, called among them by four names, viz., Bythus, and Nous, and Logos, and Anthropos. For each of these is masculo-feminine, as follows: Propator was united by a conjunction with his Ennoea; then Monogenes, that is Nous, with Aletheia; Logos with Zoe, and Anthropos with Ecclesia.

2) These Aeons having been produced for the glory of the Father, and wishing, by their own efforts, to effect this object, sent forth emanations by means of conjunction. Logos and Zoe, after producing Anthropos and Ecclesia, sent forth other ten Aeons, whose names are the following: Bythius and Mixis, Ageratos and Henosis, Autophyes and Hedone, Acinetos and Syncrasis, Monogenes and Macaria. These are the ten Aeons whom they declare to have been produced by Logos and Zoe. They then add that Anthropos himself, along with Ecclesia, produced twelve Aeons, to whom they give the following names: Paracletus and Pistis, Patricos and Elpis, Metricos and Agape, Ainos and Synesis, Ecclesiasticus and Macariotes, Theletos and Sophia.

3) Such are the thirty Aeons in the erroneous system of these men; and they are described as being wrapped up, so to speak, in silence, and known to none [except these professing teachers]. Moreover, they declare that this invisible and spiritual Pleroma of theirs is tripartite, being divided into an Ogdoad, a Decad, and a Duodecad. And for this reason they affirm it was that the "Saviour" -- for they do not please to call Him "Lord" -- did no work in public during the space of thirty years, thus setting forth the mystery of these Aeons. They maintain also, that these thirty Aeons are most plainly indicated in the parable of the labourers sent into the vineyard. For some are sent about the first hour, others about the third hour, others about the sixth hour, others about the ninth hour, and others about the eleventh hour. Now, if we add up the numbers of the hours here mentioned, the sum total will be thirty: for one, three, six, nine, and eleven, when added together, form thirty. And by the hours, they hold that the Aeons were pointed out; while they maintain that these are great, and wonderful, and hitherto unspeakable mysteries which it is their special function to develop; and so they proceed when they find anything in the multitude of things contained in the Scriptures which they can adopt and accommodate to their baseless speculations.

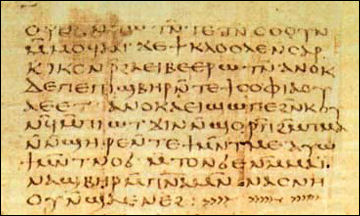

Nag Hammadi and Gnosticism

Much of what we know about gnosticism comes from the Nag Hammadi library, writings found near the Nile River in central Egypt in 1945 that illustrate the great diversity in the religious speculation and communal piety of early Christian groups. Along with the Dead Sea Scrolls, they helped historians understand the religious context out of which the earliest Christian traditions emerged.

According to Time magazine: “Gnosticism is the object of renewed interest among scholars, owing largely to the publication of a remarkable library of Gnostic scriptures. Known as the Nag Hammadi Codices, for the town in southern Egypt near the site of their discovery, the Library consists of twelve 4th century papyrus books containing 52 texts that are thought to have been translated from the original Greek into Egypt's ancient Coptic language. Many scholars believe that it will become as important to understanding the early Christian era as the Dead Sea Scrolls, the library of a Jewish Essene community that was discovered in 1947. [Source: Time, June 9, 1975 ++]

Gnostic text Apocalypse of Peter

“The Nag Hammadi texts are already adding new fuel to a longstanding debate over the relationship between Gnosticism and early Christianity. Scholars have long believed that some New Testament passages attack incipient forms of Gnosticism. The traditional explanation is that Gnosticism matured after the birth of Christianity and became its archenemy, not only as a separate religion but also as a heretical wing within the early church. Yet some experts, among them Germany's New Testament Critic Rudolf Bultmann, are persuaded that Gnosticism was a full-fledged, working religion even before the arrival of Christ. ++

“In any case, it was largely the threat posed by the Gnostics that forced the early Christian church to codify its beliefs and fix the list of authoritative Bible books. As orthodoxy won out, Gnostic scriptures were destroyed, and for centuries the religion was known chiefly from church attacks against it. The Nag Hammadi texts, says New Testament Scholar James M. Robinson, who led the team that has compiled them, offer the first comprehensive view of Gnosticism as "a religion in its own right." That view is startling indeed. The Gnostics were imaginative religious scavengers who borrowed freely from various sources to furnish their own scriptures. But they evidently felt a particular need to co-opt and corrupt elements of their rival, Christianity. Typically, two of the best-known tracts from the Nag Hammadi library, the previously published Gospel of Thomas and Gospel of Philip, contain sayings of Jesus purportedly collected by two of his Apostles but often twisted by the Gnostics to fit their own radically ascetic, relentlessly spiritual outlook. ++

See Separate Article: APOCRYPHA FROM THE NEW TESTAMENT africame.factsanddetails.com

Mandaeans — Practitioners of the Last Gnostic Religion

Mandaeans — also called Sabians — are followers of the last Gnostic religion to survive continuously from ancient times down to the present day. James F. McGrath wrote: The Mandaeans’ central ritual is baptism: immersion in flowing water, which is referred to in Mandaic as “living water,” a phrase that appears in the Bible’s New Testament as well. Baptism in Mandaean faith is not a one-time action denoting conversion as in Christianity. Instead it is a repeated rite of seeking forgiveness and cleansing from wrongdoing, in preparation for the afterlife. [Source: James F. McGrath, Professor of New Testament Language and Literature, Butler University, The Conversation, June 27, 2022]

“Baptist” today usually denotes a form of Christianity, but Mandaeans aren’t Christians. They have a special place, however, for the individual who is said to have baptized Jesus, namely John the Baptist. The Mandaean Book of John, which I was involved in translating, tells stories about John the Baptist and attributes speeches to him containing various ethical teachings. In the first half of the 20th century, the Mandaeans received significant attention from New Testament scholars who thought that their high view of John the Baptist might mean they were the descendants of his disciples. Many historians think that Jesus of Nazareth was a disciple of John the Baptist before breaking away to form his own movement, and I am inclined to agree.

Estimates vary as to how many Mandaeans there are today. Some can still be found in their historic homelands in Iraq and Iran. However, persecution in those places has led to the creation of small but significant Mandaean diaspora communities in such places as Australia, Sweden and the U.S., particularly the San Diego and San Antonio areas. This scattering, combined with Mandaeans’ dwindling numbers, has made it much harder for them to preserve their identity and pass their traditions along to the next generation. Mandaeans do not accept converts or consider children of marriages with non-Mandaeans to be part of their religious community, which has also contributed to their dwindling population.

Mandaem Literature and Art

James F. McGrath wrote: Mandaeism, like other forms of Gnosticism, is an esoteric religion whose literature remains mostly in the hands of priestly families. Their sacred texts are written in a distinctive alphabet used only for that purpose. The contents and meaning of these works are largely unknown even to most Mandaeans, never mind others. [Source: James F. McGrath, Professor of New Testament Language and Literature, Butler University, The Conversation, June 27, 2022]

But the Mandeans’ alternative view has periodically attracted popular interest. In the 19th century, their most important sacred text, the Great Treasure or Ginza Rba, was translated into Latin. That is believed to have contributed to the heightened interest in esoteric mysticism and spirituality in that era. However, this was largely among people who had no contact with or real awareness of the Mandaeans in the present day.

A number of Mandaean scrolls contain fascinating artwork and illustrations depicting varied images including the celestial figures mentioned in their texts, scenes from the afterlife, trees and animals. All are drawn in a style that isn’t quite like what one finds in the artwork or illustrated manuscripts of other religions. One of my favorite scenes in the scroll known as Diwan Abatur depicts people being tormented with trumpets and cymbals in purgatories through which souls are liable to pass. The point is most likely the loud noise such instruments can make, and not a negative statement about music in general.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024