GNOSTIC BELIEFS

The Gnostics took an intellectual and esoteric view of Christianity that downplayed the paternal and sexist aspects of Christian doctrine and took the emphasis away from guilt and sin. They saw physical experience as an illusion and believed the world and our bodies were created by an incompetent lesser god, and each individual contains a spark of divinity that Jesus’s teachings can help to develop and exploit.

James F. McGrath wrote: Gnostic religions view the material world as the product of a mistake in the heavenly realm, the creation of one or more inferior divine beings rather than the supreme God. Gnosticism also emphasizes that human beings can become aware of this and prepare their souls to escape from under the influence of the malevolent spiritual forces that created and rule this realm, so that when they die they can ascend to the good realm that lies beyond them. [Source: James F. McGrath, Professor of New Testament Language and Literature, Butler University, The Conversation, June 27, 2022]

Core gnostic beliefs: 1) Dualism - matter is evil, spirit is good; 2) Knowledge vs. Faith. Higher knowledge (revelation) is the channel of salvation; 3) Way of salvation - thru secret tradition, mysteries, asceticism (anti flesh); 4) Emanation theory to explain the existence of the world; 5) Redemption - liberate soul from matter to participate in Light, i.e. Divine Being. Concentrate on Christ's teaching; 6) Docetic- reject Incarnation; 6) Classification of people - spiritual, physical, carnal 7) Use of allegory. Tend to reject Old Testament as an account of the Demiurge. /~\

Websites and Resources: Early Christianity: Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org ; Elaine Pagels website elaine-pagels.com ; Sacred Texts website sacred-texts.com ; PBS Frontline, From Jesus to Christ, The First Christians pbs.org ; Guide to Early Church Documents iclnet.org; Early Christian Writing earlychristianwritings.com ; Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu ; BBC on Christianity bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/christianity ; Candida Moss at the Daily Beast Daily Beast Christian Classics Ethereal Library www.ccel.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Gnostic Gospels” by Elaine Pagels, Lorna Raver, et al. Amazon.com awarded a National Book Award and was a surprise bestseller;

“The Nag Hammadi Scriptures: Translation of Sacred Gnostic Texts” by Marvin W. Meyer, Elaine H. Pagels, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gnostics” by Jacques Lacarriere Amazon.com ;

“Lost Christianities: The Battles of Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew”

by Bart D. Ehrman, Matthew Kugler, et al. Amazon.com ;

“The Gospel According to Heretics: Discovering Orthodoxy through Early Christological Conflicts” by David E. Wilhite Amazon.com ;

“The Lost History of Christianity: The Thousand-Year Golden Age of the Church — and How It Died” by Philip Jenkins, Dick Hill, et al. Amazon.com ;

“Cyril of Alexandria and the Nestorian Controversy: The Making of a Saint and of a Heretic” by Susan Wessel Amazon.com ;

“Two Thousand Years of Coptic Christianity” by Otto F.A. Meinardus Amazon.com ;

“The History of the Coptic Church After Chalcedon (451-1300)” by Bishop Youanis Amazon.com ;

“Coptic Monasteries: Egypt's Monastic Art and Architecture” by Gawdat Gabra and Tim Vivian Amazon.com ;

“Backgrounds of Early Christianity” by Everett Ferguson Amazon.com ;

“After Jesus, Before Christianity: A Historical Exploration of the First Two Centuries of Jesus Movements” by Erin Vearncombe, Brandon Scott, et al. Amazon.com ;

“A History of Christianity” by Paul Johnson, Wanda McCaddon, et al. Amazon.com

Gnostic Cosmology and Divinity

Gnostics conceived of the universe as divided into two realms: the present visible world, of matter, dark and evil, and a spiritual world of light and good. Talk of a holy or divine seed… was common as a way of emphasizing the continuity between God and humanity. Things like the virgin birth, resurrection and other elements of the Jesus story are not seen by Gnostics as literal, historical events but rather are viewed as symbolic “keys” to a “higher” understanding (Tantrism serves a similar purpose in Buddhism). Gnostics, for example, see the resurrection as a symbolic event and argue that Jesus not only appeared to the Apostles but appeared to others who had prepared through the “gnosos” to receive him and his truth. This view that anyone could experience the truth of Jesus’s resurrection negated the need for clerical authority, undermining the very basis of the church, and was thus viewed as heresy.

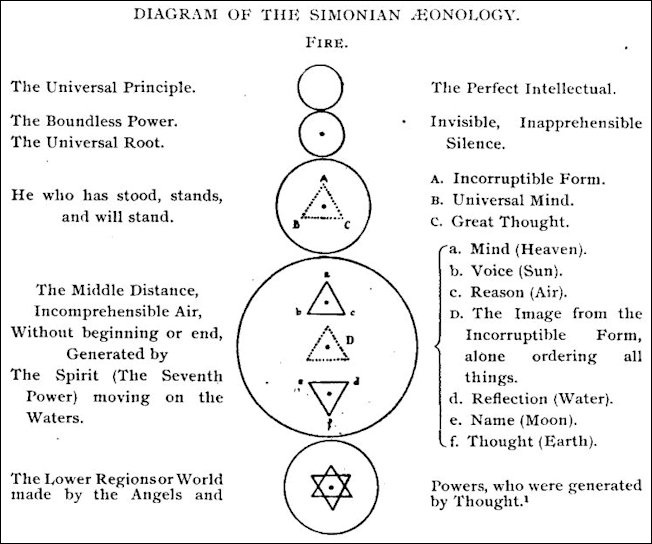

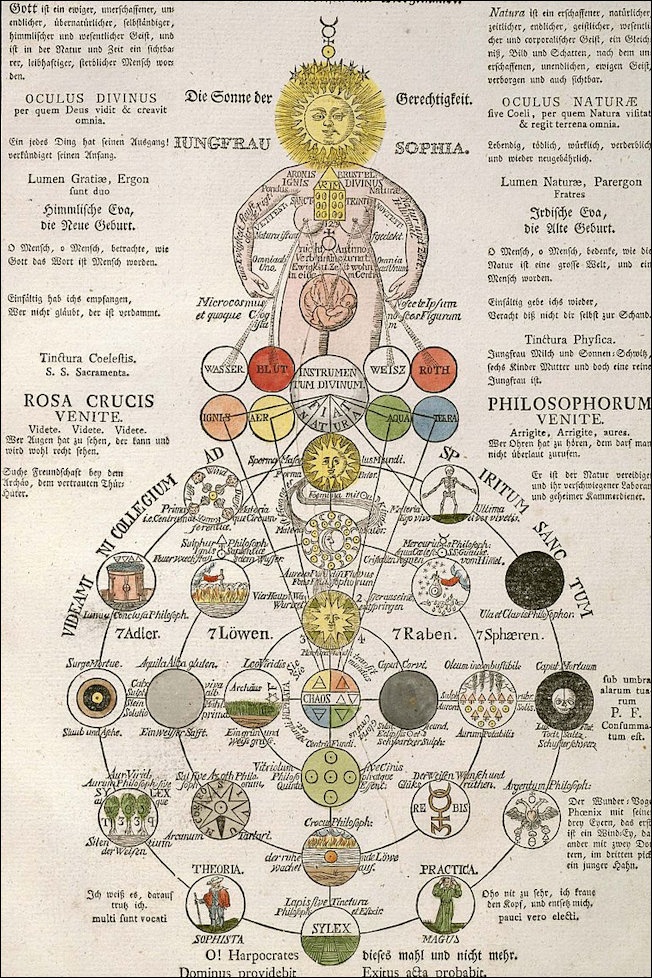

Carl A. Volz wrote: “Characteristic of gnostic teaching was the distinction between the Demiurge or Creator god, and the supreme, remote, and unknowable Divine Being. From the latter the Demiurge was derived by a longer or shorter series of emanations or aeons. He it was, who, through some mischance or fall among the higher aeons, was the immediate source of creation and ruled the world, which was therefore imperfect and antagonistic to what was truly spiritual. But into the constitution of some men there had entered a seed or spark of Divine spiritual substance, and through gnosis and the rites associated with it this spiritual element might be rescued from its evil material environment and assured of a return to its home in the Divine Being.

Such men were designated "the spiritual" (pneumatikoi), while others were merely fleshly or material (sarkikoi or hulikoi), though some gnostics added a third intermediary class, the "psychic" (psuchikoi). The function of Christ was to come as the emissary of the Supreme God, bringing gnosis. As a Divine Being he neither properly assumed a human body nor died, but either temporarily inhabited a human being, Jesus, or assumed a merely phantasmal human appearance. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

Gnostic Views on Jesus and the Resurrection

Jesus was regarded not as the son of the creator god who redeemed humanity through his death and resurrection but rather as a “bloodless spirit”: an avatar or voice of the oversoul sent to teach humans how to ignite the sacred spark within themselves. Critics of gnostic perspective view its emphasis on looking within as self indulgent and argue that one Christian strong points is its social and charitable aspects.

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “Different gnostics believed different things about the death and resurrection of Jesus. But some were people, whom we know as docetists, [who] believed that the death and suffering of Jesus were things that only appeared to happen, or if they happened, didn't really happen to the core of Jesus' spiritual reality. And so they abandoned the insistence upon those two poles of what were coming to be the heart of orthodox belief, the death and resurrection of Jesus. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“There are different texts in the opus of material that we call gnostic that are presentations of the teachings of Jesus or the person of Jesus. Some of those texts, such as the Gospel of Thomas, which is at least a semi-gnosticizing kind of production, presents Jesus simply as a teacher, a teacher of wisdom. Someone who did not suffer an ignominious death on the cross and did not experience a resurrection. So the focus on Jesus as teacher would be characteristic of a strand of Christianity that certainly comes to be gnostic.

“Another text called the Gospel of Truth is not a narrative of the death and resurrection of Jesus at all. It's a symbolic reflection on certain themes that come from scripture and are associated with the life and teachings of Jesus. But that symbolic reflection is a way of getting the the readers or hearers of that text to think about their relationship to God, their essential connection with the divine and the world of spirit....

Gnostic Beliefs about the World and Universe

The Gnostics viewed the world as a place of suffering and ignorance and the goal of individuals was to escape from it and find the true world within oneself with secret knowledge. The pursuit of special knowledge required time and may have required followers to be literate. Jesus was seen as a teacher. Salvation was regarded as something only a few could achieve. No particular importance was attached to his death and resurrection.

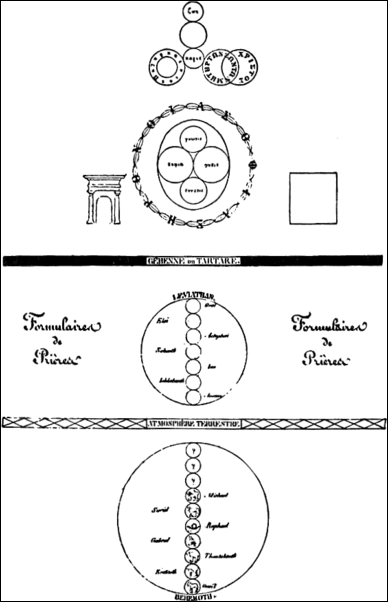

Gnostic universe Gnostics envisioned heaven and earth as "World Egg in the womb of the universe," with a giant serpent that kept the egg warm. Describing this universe, the 7th century English monk Bede wrote: "The Earth is an element placed in the middle of the world as a yolk in the middle of an egg; around it is the water, like the white surrounding the yolk; outside that is the air, like the membrane of an egg; and around all is the fire, which closed it in as the shell does."

They also believe God did not create the earth but rather produced angels that created thousands of other angels. Twelve “acons” and 72 “luminaries” also came into existence, with each luminary producing five firmaments, for a total of 360. In one text Jesus refers to the cosmos as a “corruption,” but apparently one that is better than the earth. The Gnostics viewed divinity as a kind oversoul with female and male aspects. The traditional patriarchal god of the Old Testament was given a lesser role than the creator of the corrupt world.

Gnosticism Viewed as Heresy

According to Time magazine:“"God saw everything that he had made, and behold, it was very good." So Genesis I sums up the creation of the world. But one family of Near Eastern sects had the opposite view: it believed that the Creator and his work were evil, and that men's souls were imprisoned by earthly life. The only escape was salvation through possession of an esoteric gnosis (Greek for knowledge), which led to union with an abstract supreme being. Such was the creed of Gnosticism, a strange amalgam of beliefs that was orthodox Christianity's main rival in the early centuries after Christ. [Source: Time, June 9, 1975 ++]

“The Gnostics believed that a spark of divine light was imprisoned in some men's bodies, and that redemption meant union with the supreme being through possession of the mystical, Zenlike gnosis; a Gnostic could thus achieve gnosis and partial redemption long before corporeal death. The Gnostic creed left no room for the Christian belief in redemption through Christ's atonement on the cross for the sins of mankind. In fact, Nag Hammadi texts depict a Jesus who did not die on the cross at all. In their version, Simon of Cyrene carried the cross to Golgotha and-by ghoulish accident-was crucified in Christ's place while Jesus looked down from above and laughed.

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “By the end of the second century there was considerable debate among Christian teachers, theologians, about how best to articulate Christian belief. Gnostics are charged by their their critics with making a fundamental mistake about the relationship between God as creator and God as redeemer. And they seem to suggest, at least some of them seem to suggest that the divine power that created this world is an inferior being, inferior to the true spiritual God who desires the salvation of all human beings, or at least all of those human beings who are capable of knowledge. That distinction between the belief in creation and belief in redemption was viewed by theologians such as Irenaeus as to be a fundamental mistake which departed radically from the testimony of scripture. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“Another thing that gnostics worried about was the relationship between the divine element and the human element in Jesus, and in some cases they seem to have made a similar sort of distinction between the divine and the human that put those into sharp opposition, an opposition that was viewed as a mistake by their critics. By making that distinction they tended to denigrate the physical humanity of Jesus, and orthodox teachers such as Irenaeus by the end of the second century wanted to insist very strongly on the humanity of Jesus as an example for his followers, so it was very important to insist on Jesus as really suffering and dying on the cross because Christians were being called upon at that time to suffer and die as witnesses, as martyrs to their faith. And if with some gnostics you could denigrate the physical suffering of Jesus, you might call into question that obligation to stand and to bear witness for the faith.

"Heretics" Defined in Response to Persecution

Vespers altar in a modern Gnostic church

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “As far as we can tell, the earliest Christian communities had an enormous variety of viewpoints and attitudes and approach, as we've said. But by the end of the second century, you begin to see hierarchies of bishops, priests and deacons emerge in various communities and claim to speak for the majority. And with that development, there's probably an assertion of leadership against viewpoints that those leaders considered dangerous and heretical. One of the issues that polarized those communities, perhaps the most urgent and pressing issue, was persecution. That is, these people, all Christians, belonged to an illegal movement. It was dangerous to belong to this movement. You could be arrested, if you were charged with being a Christian, you could be put on trial, you could be tortured and executed if you refused to recant. And with that pressure, many said, "We want to know when a person joins this movement if that person is going to stand with us or is going to pretend they're not with us. So let's clarify who belongs to us...." [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“The Bishop Irenaeus was about 18 to 20 years old when his little community was absolutely decimated by a devastating persecution. They say that 50 to 70 people in two small towns were tortured and executed. That must have meant hundreds were rounded up and put in prison. But 50 to 70 people in two small towns executed in public is a devastating destruction of that beleaguered community. And Irenaeus was trying to unify those who were left. What frustrating him is that they didn't all believe the same thing. They didn't all gather under one kind of leadership. And he, like others, was deeply aware of the dangers of fragmentation, that one community could be lost. And so it is out of that deep concern, I think, that Irenaeus and others began to try to unify the church, and, and create criteria like, you know, these are the four gospels. These are what we believe, these are the rituals, which you first do. You're baptized and then you're a member of this community. It would be absurd to suggest that the leaders of the church were out to protect their power.

“Because to become bishop in a church in which the 92 year old bishop had just died in prison, which is what Irenaeus did as a very young man, he had the courage to become bishop, is to become a target for the next persecution. This is not a position of power, it's a position of danger and courage. And those people were concerned to try to unify the church. So it would be ridiculous to tell the story of the early Christian movement as though the orthodox were, you know, power mad, and trying to destroy all diversity in the church. It's much more complicated than that. The sociologist Max Weber has shown that a religious movement, if it doesn't develop a certain institutional structure within a generation of its founder's death, will not survive. So it's likely, I think, that we owe the survival of the Christian movement to those forms that Irenaeus and others developed. You know, the list of acceptable books, the list of acceptable teachings, the rituals.”

Gnosticism and Christianity

According to Time magazine: “Christianity and Gnosticism both flourished during the unraveling of the Roman Empire, but dealt with this era of upheaval in different ways. The more optimistic Christians came to terms with the secular world; they embraced the belief that God had become incarnate on earth in the person of Jesus Christ, as well as the Jewish idea of a "good" creation. It was the world-hating Gnostics, says Robinson, who "expressed most clearly the mood of defeatism and despair that swept the ancient world." [Source: Time, June 9, 1975 ++]

“The true God, the Gnostics reasoned, could not have created anything so despicable as the material world. Another supreme being emerges in Gnostic tracts: an abstract figure who embodies absolute truth and light and rules an invisible, heavenly realm. The lowest being in this realm is a woman, Sophia (Greek for wisdom), who offends the supreme being by producing a child without a mate; her offspring, a malevolent false god named Yaldabaoth, created the material world. He is thus an evil parody of the Old Testament creator revered by Jews and Christians. ++

“Other elements of the Bible are similarly warped in the Gnostic scriptures. For example, the Gnostics viewed the serpent of the Garden of Eden as a hero rather than a villain, because he helped reveal the secrets of the Tree of Knowledge that Yaldabaoth had jealously kept from Adam and Eve. Yaldabaoth, working in league with Noah, tried to exterminate the knowledge-seeking Gnostics with a worldwide flood. Later on, he attacked them with brimstone when they sought refuge in the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. ++

Carl A. Volz wrote: “The principal anti-gnostic writers, such as Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Hippolytus, emphasized the pagan features of gnosticism, and appealed to the plain sense of the Scriptures as interpreted by the tradition of the Church, which had been publicly handed down by a chain of teachers reaching back to the Apostles. They insisted on the identity of the Creator and the Supreme God (1st Article ApCreed), on the goodness of the material creation, and on the reality of the earthly life of Jesus, especially of the Crucifixion and Resurrection (2nd Article ApCreed). Man needed redemption from an evil will rather than an evil environment. The sect of the Manichees founded by Mani the Persian in the 3rd Century and widely influential for over a century in the Roman empire, closely resembled the earlier gnostic sects, as do some of the modern forms of Theosophy. [Source: Carl A. Volz, late professor of church history at Luther Seminary, web.archive.org, martin.luthersem.edu]

Two ways to model the effect of Gnosticism on the Church: 1) + Canon + Rule of Faith + Apostolic succession; 2) + Episcopal authority + Mysticism and asceticism in the Church

Gnosticism Today

According to Time magazine: As of 1975, “Gnosticism survives as a living religion only among the Mandaean marsh dwellers of Iraq. But Robinson believes that the Gnostic world view has had a kind of underground existence throughout Western civilization, surfacing in such classics of existential despair as Albert Camus' The Stranger as well as among today's alienated youths. Says Robinson: "The Gnostics were colossal dropouts who opted for an otherworldly escape." [Source: Time, June 9, 1975 ++]

Mandaeans are an ethnoreligious group indigenous to the alluvial plain of southern Mesopotamia and are followers of Mandaeism, a Gnostic religion. The Mandaeans were originally native speakers of Mandaic, a Semitic language that evolved from Eastern Middle Aramaic, before many switched to colloquial Iraqi Arabic and Modern Persian. Mandaic is mainly preserved as a liturgical language. In the aftermath of the Iraq War of 2003, the indigenous Mandaic community of Iraq, which used to number 60–70,000 persons, collapsed; most of the community relocated to nearby Iran, Syria and Jordan, or formed diaspora communities beyond the Middle East. The other indigenous community of Iranian Mandaeans has also been dwindling as a result of religious persecution over that decade.” [Source: Wikipedia +]

Mystical Sophia

Mandaeans are a closed ethno-religious community, practicing Mandaeism, which is a Gnostic religion. Its adherents revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enosh, Noah, Shem, Aram and especially John the Baptist, but reject Abraham, Moses and Jesus of Nazareth. The Mandaeans group existence into two main categories: light and dark. They have a dualistic view of life, which encompasses both good and evil; all good is thought to have come from the World of Light (i.e. lightworld) and all evil is considered to be a product of the World of Darkness. In relation to the body–mind dualism coined by Descartes, Mandaeans consider the body, and all material, worldly things, to have come from the Dark, while the soul (sometimes referred to as the mind) is a product of the lightworld. Mandaeans believe the World of Light is ruled by a heavenly being, known by many names, such as “Life,” “Lord of Greatness,” “Great Mind,” or “King of Light” (Rudolph 1983). +

The Lord of Darkness is the ruler of the World of Darkness and was formed from dark waters representing chaos (1983). A main defender of the darkworld is a giant monster, or dragon, with the name “Ur;” an evil, female ruler also inhabits the darkworld, known as “Ruha” (1983). The Mandaeans believe these malevolent rulers created demonic offspring who consider themselves the owners of the Seven (planets) and Twelve (Zodiac signs) (1983). +

According to Mandaean beliefs, the world (i.e. Earth) is a mixture of light and dark created by the demiurge (Ptahil) with help from dark powers, such as Ruha, the Seven, and the Twelve (1983). Adam’s body (i.e. believed to be the first human created by God in Christian tradition) was fashioned by these dark beings; however, his “soul” (or mind) was a direct creation from the Light. Therefore, many Mandaeans believe the human soul is capable of salvation because it originates from the lightworld. The soul, sometimes referred to as the “inner Adam” or “hidden Adam,” is in dire need of being rescued from the Dark, so it may ascend into the heavenly realm of the lightworld (1983). +

Baptisms are a central theme in Mandaeanism, believed to be necessary for the redemption of the soul. Mandaeans do not perform a single baptism, as in religions such as Christianity; rather, they view baptisms as a ritualistic act capable of bringing the soul closer to salvation (McGrath 2015). Therefore, Mandaeans get baptized numerous times during their lives. John the Baptist is a key figure for the Mandaeans; they even consider him to have been a Mandaean himself (2015). John is referred to as a “disciple” or “priest,” most known for the countless number of baptisms he performed, which helped close the immense gap between the soul and salvation (Rudolf 1983).

Today, many Mandaeans are refugees and are not willing to accept converts into their religion (McGrath 2015). Sunday, as in other religious traditions, is their holy day, centered largely on mythical beliefs. Some Mandaeans consider Jesus an “apostate Mandaean” (McGrath 2015), and today they tell a story of how a Mandaean messenger went to Jerusalem and claimed Jesus Christ as a liar and false prophet (Rudolf 1983).

Holy Wisdom

Gnostic Texts

Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe wrote for the BBC: “Until the 20th century, most information about the Gnostics was to be found in Christian texts attacking Gnosticism and its variants. But in 1945, a collection of over 40 Coptic texts, ranging in likely date, was found at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt. “These texts included books purporting to preserve Jesus’s secret teachings, as well as gospels supposedly written by his disciples, by his twin brother Thomas and by his brother James. These texts, in addition to other related texts found elsewhere, are collectively called the 'Gnostic Gospels'. The Gnostic Gospels were theologically problematic, mentioning multiple gods and the creation of an evil world. |::| “It is no surprise that these ancient Christian texts did not make it into the Bible. The process of establishing which books should be part of the Christian canon had begun early. Marcion was the first to propose a particular canon in the mid-second century, and from then on different Christian groups disputed hotly which combinations of writings should be included or excluded. [Source: Dr Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe, BBC, February 17, 2011]

Documents — generally classed by scholars as Gnostic — were known prior to the Nag Hammadi Library discovery. These include “The Gospel of Mary” (Magdalene). Modern understanding of Gnosticism was grounded upon these documents (many of which became available only in the last half of the nineteenth century) and upon the comments of the early Christian "patristic heresiologists" until the discovery of the Gnostic library at Nag Hammadi in 1945. The Nag Hammadi Library texts have helped put all of these previously know documents into a more complete context. [Gnostic Society ^]

Classical Gnostic Scriptures and Fragments: Texts from the Askew Codex. The Askew codex was bought by the British Museum in 1795, having been previously acquired by a Dr. Askew from an unknown source. It is more commonly known by the name inscribed upon it's binding, "Piste Sophiea Coptice". G.R.S. Mead suggests a more appropriate name might be "Books of the Savior". ^

“ Texts from the Bruce Codex. This codex of Coptic, Arabic and Ethiopic manuscripts was found in upper Egypt by a Scottish traveler, James Bruce in about 1769. The first translations of the text began to be made in the mid-1800's. ^

“Texts from the Berlin Gnostic Codex (Akhmim Codex, Papyrus Berolinensis 8502) - including The Gospel of Mary. This Coptic codex was acquired in Cairo in 1896. It contains portions of three Gnostic texts now known as the Apocryphon of John, the Sophia of Jesus Christ, and the Gospel of Mary. Despite the importance of the find, several misfortunes including two wars delayed its publication until 1955. By then the Nag Hammadi texts had also appeared, and it was found that portions of two texts in this codex were also present in the Nag Hammadi library: the Apocryphon of John, and the Sophia of Jesus Christ. Both of these texts from the Berlin Gnostic Codex were used to augment the translations of the Apocryphon of John and the Sophia of Jesus Christ which appear in the Nag Hammadi collection. Also include in the codex is the only surviving copy of the Gospel of Mary (Magdalene): ^

“Gospel of Thomas fragments in the Papyrus Oxyrhynchus: In 1897 and 1903 three ancient fragments from a Greek version of the Gospel of Thomas were discovered during archeological excavations at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt. It was initially unclear what document might have originally preserved these sayings of Jesus -- the Gospel of Thomas had been lost to history. But the discover in 1945 of a complete and well-preserved version of Thomas in Coptic made it possible to identify the Oxyrhynchus texts as belonging to a lost Greek edition of the Thomas Gospel. The three Oxyrhynchus fragments preserve several logion found in the complete Coptic version of the Gospel of Thomas -- OxyP 1 (which stands for "Oxyrhynchus papyrus fragment 1") contains sayings 26 to 30, 77, and 30 to 31; OxyP 654 contains sayings 1 to 7; OxyP 655 preserves sayings 36 to 40. This allows comparison of the Coptic texts with the original Greek version (the Gospel was originally written in Greek) and helps validate the surviving version of Thomas. ^

“Gnostic Acts and Other Classical Texts. Despite efforts of the evolving orthodoxy to destroy all Gnostic scriptures and documents, a few texts did survive which contained extensive sections of clearly Gnostic character and provenance. The primary examples of these are the sections known as the "Hymn of Jesus" within the Acts of John and the "Hymn of the Pearl" in the Acts of Thomas. ^

Gnostic Documents

Documents labeled as Gnostic include

“The Hymn of Jesus and The Mystery of the Cross” From The Acts of John

“The Acts of John”

“Hymn of the Pearl,” from the Acts of Thomas. This is a beautiful, classic Gnostic myth.

“The Acts of Thomas”

“The Odes of Solomon” (“Song of Songs” from the Old Testament)

“The Secret Gospel of Mark”, discovered by Prof. Morton Smith in 1958.

“Gnostic Fragments in Patristic Sources”: In the polemical writings of the Church Fathers against the Gnostics, several fragments of their (soon to be destroyed) works were preserved. Many of these are collected here, with the source noted.

“The Naassene Psalm”, an excerpt quoted by Hippolytus in Refutations.

“Basilides: Fragments from his Writings”, collected from works by Hippolytus, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen. [At Gnostic Society ^]

“Ptolemy: Commentary on the Gospel of John Prologue”, Found in Irenaeus, Against Heresies. “Ptolemy: Letter to Flora”, Found in Epiphanius, Against Heresies. “Epiphanes: On Righteousness”, aound in Clement of Alexandria, Stromaties. “Theodotus: The Excerpta Ex Theodoto,” found in Clement of Alexandria, Stromaties “Heracleon: Fragments from his Commentary on the Gospel of John”, Found in Origen, Commentary on the Gospel of John “The Ophite Diagrams”, Celsus' and Origen's descriptions of a Gnostic diagram used by the Ophites

Gnostic Scriptures and Fragments Marcion: Gospel of the Lord and Other Writings. Marcion the Apostle John, to whom he "brought scriptures from the Pontic brethren..." The Gospel of the Lord has been reconstructed from extant sources. The text is divided into 6 sections, each referenced to parallel chapters in the Gospel of Luke. 1) Section I (Luke 3:1-7:50); 2) Section II (Luke 8:1-10:24); 3) Section III (Luke 10:25-13:17); 4) Section IV (Luke 13:18-17:37); 5) Section V(Luke 18:1-21:38); 6) Section VI (Luke 22:1-24:47) ^

Other Writings by Marcion “Marcion: To the Galatians: Patristic Writings Against Marcion Tertullian: Against Marcion, Booka 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. Book 4 is the principal book dealing with Marcion's Gospel “St. Ephraim: Third Discourse to Hypatius Against Mani, Marcion, and Bardaisan ^

Books About Marcion An Overview of Marcion — From G.R.S. Mead, Fragments of a Faith Forgotten Marcion — From Adolf von Harnack, History of Dogma (1901). Sinope: Some Thoughts Concerning Marcion's Geographical World — An essay by David Anderson. Antithesis or "Contradictions" between the Old Testament Deity and the New Testament God — an essay by Daniel Mahar. Daniel Mahar and the The Center for Marcionite Research who have collected, edited and contributed to the Archive the fine collection of materials found in this section.

Valentinus was one of the most influential Gnostic Christian teachers of the second century A.D. He founded a movement which spread throughout Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. Despite persecution by the Catholic Church, the Valentinian school endured for over 600 years. Valentinus' influence persists even today. This site is dedicated to the Valentinian Gnostic tradition and features scriptures as well as articles on the teachings of the school.

An excellent introduction to Valentinus and his tradition is also given by Dr. Stephan Hoeller in Valentinus: A Gnostic for All Seasons, available in the Archives. “Contents of the Valentinian Tradition Section”: 1) Who was Valentinus?; 2) The Valentinian School; 3) Teachings in Brief; 4) Teachings in Detail; 5) Virtual Library; 6) Valentinians and the Bible; 7) Detailed Articles (18 Essays on Specific Themes)

For information on these texts and texts themselves See the Gnostic Society Library gnosis.org

Nag Hammadi Texts

The Nag Hammadi Library, a collection of thirteen ancient books (called "codices") containing over fifty texts, was discovered in upper Egypt in 1945. This immensely important discovery includes a large number of primary "Gnostic Gospels" – texts once thought to have been entirely destroyed during the early Christian struggle to define "orthodoxy" – scriptures such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of Truth. Many scriptures in the Nag Hammadi collection were influenced by Valentinus (c. 100–160 AD) and his tradition of Gnosis. The discovery and translation of the Nag Hammadi library, initially completed in the 1970's, has provided impetus to a major re-evaluation of early Christian history and the nature of Gnosticism. [Source: Gnostic Society]

According to the Gnostic Society: “ When analyzed according to subject matter, there are roughly six separate major categories of writings collected in the Nag Hammadi codices: 1) Writings of creative and redemptive mythology, including Gnostic alternative versions of creation and salvation: The Apocryphon of John; The Hypostasis of the Archons; On the Origin of the World; The Apocalypse of Adam; The Paraphrase of Shem. (For an in-depth discussion of these, see the Archive commentary on Genesis and Gnosis.) [Source: Gnostic Society]

2) “Observations and commentaries on diverse Gnostic themes, such as the nature of reality, the nature of the soul, the relationship of the soul to the world: The Gospel of Truth; The Treatise on the Resurrection; The Tripartite Tractate; Eugnostos the Blessed; The Second Treatise of the Great Seth; The Teachings of Silvanus; The Testimony of Truth. 3) “Liturgical and initiatory texts: The Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth; The Prayer of Thanksgiving; A Valentinian Exposition; The Three Steles of Seth; The Prayer of the Apostle Paul. (The Gospel of Philip, listed under the sixth category below, has great relevance here also, for it is in effect a treatise on Gnostic sacramental theology). ^

4) “Writings dealing primarily with the feminine deific and spiritual principle, particularly with the Divine Sophia: The Thunder, Perfect Mind; The Thought of Norea; The Sophia of Jesus Christ; The Exegesis on the Soul. 5) Writings pertaining to the lives and experiences of some of the apostles: The Apocalypse of Peter; The Letter of Peter to Philip; The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles; The (First) Apocalypse of James; The (Second) Apocalypse of James, The Apocalypse of Paul. 6) Scriptures which contain sayings of Jesus as well as descriptions of incidents in His life: The Dialogue of the Saviour; The Book of Thomas the Contender; The Apocryphon of James; The Gospel of Philip; The Gospel of Thomas. ^

See Separate Article: NAG HAMMADI TEXTS factsanddetails.com

Thunder Perfect Mind

Apocalypse of Peter

Professor Harold W. Attridge told PBS: “The hymn "Thunder, the Perfect Mind" is a series of riddles which make contradictory statements about some sort of mysterious figure. Riddles such as, "I am the mother, and I am the daughter. I am the wife and I am the whore." Well, that kind of text evokes the question, who is the I that's speaking? And so this text probably was a text used to stimulate meditation upon some spiritual principle, whatever that spiritual principle was. The revealer figure, for instance, the divine wisdom that many gnostics saw as an important figure in the history of salvation. [Source: Harold W. Attridge, The Lillian Claus Professor of New Testament Yale Divinity School, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

Professor Elaine H. Pagels told PBS: “'Thunder Perfect Mind' is a marvelous, strange poem. It speaks in the voice of a feminine divine power, but one that unites all opposites. One that is not only speaking in women, but also in all people. One that speaks not only in citizens, but aliens, it says, in the poor and in the rich. It's a poem which sees the radiance of the divine in all aspects of human life, from the sordidness of the slums of Cairo or Alexandria, as they would have been, to the people of great wealth, from men to women to slaves. In that poem, the divine appears in every, and the most unexpected, forms.... [Source: Elaine H. Pagels, The Harrington Spear Paine Foundation Professor of Religion Princeton University, Frontline, PBS, April 1998 ]

“'Thunder Perfect Mind' may have been written in Egypt. It's probably written by somebody who knows the traditions of Isis, knows the traditions of the Jews. It shows that this movement grew up in a world in which Jewish, Egyptian, Greek, Roman traditions are mingled and mixing and well-known to many sophisticated people. All you had to do is travel around a city, like Carnac, and you saw all these images, and these various religions and these various cultures mixing.'

Beginning of “Thunder, Perfect Mind”

“Thunder, Perfect Mind” begins:

“I was sent forth from the power,

and I have come to those who reflect upon me,

and I have been found among those who seek after me.

Look upon me, you who reflect upon me,

and you hearers, hear me.

You who are waiting for me, take me to yourselves.

And do not banish me from your sight.

And do not make your voice hate me, nor your hearing.

Do not be ignorant of me anywhere or any time. Be on your guard!

Do not be ignorant of me.

For I am the first and the last.

[Source: Translated by George W. MacRae, James M. Robinson, ed., “The Nag Hammadi Library,” HarperCollins, San Francisco, 1990]

Wisdom

I am the honored one and the scorned one.

I am the whore and the holy one.

I am the wife and the virgin.

I am

I am the members of my mother.

I am the barren one

and many are her sons.

I am she whose wedding is great,

and I have not taken a husband.

I am the midwife and she who does not bear.

I am the solace of my labor pains.

I am the bride and the bridegroom,

and it is my husband who begot me.

I am the mother of my father

and the sister of my husband

and he is my offspring.

“I am the slave of him who prepared me.

I am the ruler of my offspring.

But he is the one who begot me before the time on a birthday.

And he is my offspring in (due) time,

and my power is from him.

I am the staff of his power in his youth,

and he is the rod of my old age.

And whatever he wills happens to me.

I am the silence that is incomprehensible

and the idea whose remembrance is frequent.

I am the voice whose sound is manifold

and the word whose appearance is multiple.

I am the utterance of my name.

“Why, you who hate me, do you love me,

and hate those who love me?

You who deny me, confess me,

and you who confess me, deny me.

You who tell the truth about me, lie about me,

and you who have lied about me, tell the truth about me.

You who know me, be ignorant of me,

and those who have not known me, let them know me.

For I am knowledge and ignorance.

I am shame and boldness.

I am shameless; I am ashamed.

I am strength and I am fear.

I am war and peace.

Colegium

Give heed to me.

I am the one who is disgraced and the great one.

Give heed to my poverty and my wealth.

Do not be arrogant to me when I am cast out upon the earth,

and you will find me in those that are to come.

And do not look upon me on the dung-heap

nor go and leave me cast out,

and you will find me in the kingdoms.

And do not look upon me when I am cast out among those who

are disgraced and in the least places,

nor laugh at me.

“And do not cast me out among those who are slain in violence.

But I, I am compassionate and I am cruel.

Be on your guard!

Do not hate my obedience

and do not love my self-control.

In my weakness, do not forsake me,

and do not be afraid of my power.

For why do you despise my fear

and curse my pride?

But I am she who exists in all fears

and strength in trembling.

I am she who is weak,

and I am well in a pleasant place.

I am senseless and I am wise.

Why have you hated me in your counsels?

For I shall be silent among those who are silent,

and I shall appear and speak,

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Christian Origins sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File); “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); King James Version of the Bible, gutenberg.org; New International Version (NIV) of The Bible, biblegateway.com; Christian Classics Ethereal Library (CCEL) ccel.org , Frontline, PBS, Wikipedia, BBC, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Live Science, Encyclopedia.com, Archaeology magazine, Reuters, Associated Press, Business Insider, AFP, Library of Congress, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024