SHEEP

Most wool comes from sheep. They are regarded as one of the most valuable domestic animals. They are raised for milk and meat and other food products as well as wool. In some places people drink sheep's milk and use it to make cheese. Like goats sheep reproduce quickly and survive in harsh conditions.

Sheep are related to goats. Both animals produce hair that can be used to make clothing. The most obvious difference between the two animals is that the tails and horns of goats stand up while the tails of sheep hang down and their horns curl. Male goats have beards while male sheep don't. Sheep have tear bags, or pits beneath their the inner corners of their eyes, Goats do not.

A male sheep is called a ram or buck. A female is called a ewe or dam. Young are called lambs. A group is called a flock and used to be called a hurtle. Ewes usually give birth to one or two lambs in the spring. One day after being born the lambs are strong enough to follow their mothers.

According to the Guinness Book of Records, the largest sheep ever recorded weighed 545 pounds; the oldest one died a week before its 29th birthday; and the largest sheep litter was eight lambs. The world record for fleece is 65 pounds of wool from fleece 25 inches long (grown over 7 years). The highest price every paid for a sheep was $358,750 for Collinsville stud JC&S 43 bought by Willogolech Pty. Ltdin 1989 at the Adelaide Eam Sales.

Cattle, sheep, goats, yaks, buffalo, deer, antelopes, giraffes, and their relatives are ruminants — cud-chewing mammals that have a distinctive digestive system designed to obtain nutrients from large amounts of nutrient-poor grass. Ruminants evolved about 20 million years ago in North America and migrated from there to Europe and Asia and to a lesser extent South America, where they never became widespread. See Ruminants Under MAMMALS: HAIR, HIBERNATION AND RUMINANTS factsanddetails.com

See Separate Article: WILD GOATS AND SHEEP OF CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com

Sheep Characteristics and Diet

Sheep range in weight from 20 to 200 kilograms (44 to 440 pounds) and generally have a head and body length that ranges from 1.2 to 1.8 meters (4 to 6 feet) and have a shoulder height of 0.65 of 1.3 meters (2 to 4.2 feet). Female sheep tend to be three quarters to two thirds the size of males. Wild sheep have tails between 7 and 15 centimeters but in domestic sheep tails may be larger and used as a fat reserve, although these long tails are removed on most commercial farms. [Source: Chris Reavill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The physical characteristics of domestic sheep vary greatly among the 200 or so breeds but there are some commonalities. Sheep have a vertical cleft and narrow snout completely covered with short hair except on the margins of the nostrils and lips. The genus Ovis is characterized by the presence of glands situated in a shallow depression in the lacrimal bone, the groin area, and between the two main toes of the foot. These glands secrete a clear semi-fluid substance that gives domestic sheep their characteristic smell.

The skulls of domesticated sheep differ from those of wild sheep in that the eye socket and brain case are reduced. Selection for economically important traits has produced domestic sheep with or without wool, horns, and external ears. Coloration ranges from milky white to dark brown and black.

Domestic sheep are extremely hardy animals and can survive on a diet consisting of only cellulose, starch or sugars as an energy source and a nitrogen source which need not be protein. In general, sheep feed mainly on grasses while in pastures and can be fed a wide variety of hays and oats. Considerable research has been done on sheep nutritional requirements, and feed substitution tables are present in Ensminger's 1965 "The Stockman's Handbook". Grazing sheep ingest a large amount of food in a short time, then retire to rest and rechew the ingested matter. Sheep spend their day alternating between these periods of grazing and ruminating. Ovis aries has a large and complex stomach which is able to digest highly fibrous foods that can not be digested by many other animals. Its modest nutritional requirements contribute to its economic significance.

Bovids (Antelopes, Cattle, Gazelles, Goats, Sheep)

Gaucho in Patagonia Domesticated sheep are bovids. Bovids (Bovidae) are the largest of 10 extant families within Artiodactyla, consisting of more than 140 extant and 300 extinct species. According to Animal Diversity Web: Designation of subfamilies within Bovidae has been controversial and many experts disagree about whether Bovidae is monophyletic (group of organisms that evolved from a single common ancestor) or not. [Source: Whitney Gomez; Tamatha A. Patterson; Jonathon Swinton; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Wild bovids can be found throughout Africa, much of Europe, Asia, and North America and characteristically inhabit grasslands. Their dentition, unguligrade limb morphology, and gastrointestinal specialization likely evolved as a result of their grazing lifestyle. All bovids have four-chambered, ruminating stomachs and at least one pair of horns, which are generally present on both sexes.

While as many as 10 and as few as five subfamilies have been suggested, the intersection of molecular, morphological, and fossil evidence suggests eight distinct subfamilies: Aepycerotinae (impalas), Alcelaphinae (bonteboks, hartebeest, wildebeest, and relatives), Antilopinae (antelopes, dik-diks, gazelles, and relatives), Bovinae (bison, buffalos, cattle, and relatives), Caprinae (chamois, goats, serows, sheep, and relatives), Cephalophinae (duikers), Hippotraginae (addax, oryxes, roan antelopes, sable antelopes, and relatives), and Reduncinae (reedbucks, waterbucks, and relatives).

See Separate Article: BOVIDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SUBFAMILIES factsanddetails.com

Artiodactyls (Even-Toed Ungulates)

Bovids are artiodactyls. Artiodactyls are the most diverse, large, terrestrial mammals alive today. According to Animal Diversity Web: They are the fifth largest order of mammals, consisting of 10 families, 80 genera, and approximately 210 species. As would be expected in such a diverse group, artiodactyls exhibit exceptional variation in body size and structure. Body mass ranges from 4000 kilograms in hippos to two kilograms in lesser Malay mouse deer. Height ranges from five meters in giraffes to 23 centimeters in lesser Malay mouse deer. [Source: Erika Etnyre; Jenna Lande; Alison Mckenna; John Berini, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Artiodactyls are paraxonic, that is, the plane of symmetry of each foot passes between the third and fourth digits. In all species, the number of digits is reduced by the loss of the first digit (i.e., thumb), and many species have second and fifth digits that are reduced in size. The third and fourth digits, however, remain large and bear weight in all artiodactyls. This pattern has earned them their name, Artiodactyla, which means "even-toed". In contrast, the plane of symmetry in perissodactyls (i.e., odd-toed ungulates) runs down the third toe. The most extreme toe reduction in artiodactyls, living or extinct, can be seen in antelope and deer, which have just two functional (weight-bearing) digits on each foot. In these animals, the third and fourth metapodials fuse, partially or completely, to form a single bone called a cannon bone. In the hind limb of these species, the bones of the ankle are also reduced in number, and the astragalus becomes the main weight-bearing bone. These traits are probably adaptations for running fast and efficiently. /=\

Artiodactyls are divided into three suborders. 1) Suiformes includes the suids, tayassuids and hippos, including a number of extinct families. These animals do not ruminate (chew their cud) and their stomachs may be simple and one-chambered or have up to three chambers. Their feet are usually 4-toed (but at least slightly paraxonic). They have bunodont cheek teeth, and canines are present and tusk-like. 2) The suborder Tylopoda contains a single living family, Camelidae. Modern tylopods have a 3-chambered, ruminating stomach. Their third and fourth metapodials are fused near the body but separate distally, forming a Y-shaped cannon bone. The navicular and cuboid bones of the ankle are not fused, a primitive condition that separates tylopods from the third suborder, Ruminantia. 3) This last suborder includes the families Tragulidae, Giraffidae, Cervidae, Moschidae, Antilocapridae, and Bovidae, as well as a number of extinct groups. In addition to having fused naviculars and cuboids, this suborder is characterized by a series of traits including missing upper incisors, often (but not always) reduced or absent upper canines, selenodont cheek teeth, a three or 4-chambered stomach, and third and fourth metapodials that are often partially or completely fused. /=\

See Separate Article: ARTIODACTYLS (EVEN-TOED UNGULATES): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Taxonomy of Sheep and Goats

The taxonomy of the genus Ovis (sheep) is controversial. Various authorities have lumped domestic sheep (O. aries) with mouflon (O. orientalis) as members of the same species. Others recognize the two as distinct species, but claim that Mouflon is the ancestral species from which domestic sheep were derived. Some consider populations of sheep on the islands of Corsica and Sardinia as subspecies of Mouflon, whereas others separate them as a distinct species. In north India, populations of Argali and urial occur near one another, and some think they represent a single species. There are also those who consider Mouflon and urial (Ovis vignei), usually considered two species, to be a single species. [Source: Andrew Hagen, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Complicating matters further, the genus Ovis has also been considered by some to be synonymous with the genus Capra (goats) because of fertile hybrids produced between domestic goats (C. hircus) and domestic sheep.

All wild species of sheep are allopatric, however, hybridization can, and does, occur.Urial sheep represent a chromosomal, geographic and morphological extreme amongst the wild sheep of Iran. Urial sheep (2N=58) hybridize with Ovis orientalis (2N=54), producing a 150 kilometer zone of hybridization. Hybrids in the hybridization zone display variable fur and chromosome number (54-58).

Domestication and Early History of Sheep

ancient goat-like sheepPeople have worn wool for at least 12,000 years. Early wool was taken from wild sheep and goats and was likely worn with the skin attached it and as primitive felt by mashing the fibers together long before it was made into anything resembling fabric.

Sheep were first domesticated in Western Asia (Turkey, Syria and Iran) from Asiatic moufflon Ancient sheep roamed pastures and grassland with people for at least 11,000 years and are thought to have been domesticated at least 9,000 ago. Sheep bones, dated to 9000 B.C., found at a site called Zawi Chemi Shandidir in the foothills of the Zagros mountains in what is now Iran, suggests that sheep were being kept in herds at that time.

There is still a lively debate over when and from where and what wild species the first domestic sheep descended. Current chromosomal and archeological evidence indicates that the divergence occurred about 9,000 to 11000 years ago and that the first sheep domesticated were mounflon (Ovis musimon) from flocks in Sardinia and Corsica.[Source: Chris Reavill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Varieties of wild goat and sheep are found in mountain regions in Asia, Europe and North America. Prehistoric sheep had dark hairy coats, horns and their wool could be pulled off by hand. Their closest relatives today are the sheep that are kept off the Shetland Islands off Scotland and the wild Soay, sheep on the uninhabited island of St. Kilda off the west coast of Scotland.

Sheep, some argue, have been as important to civilization as agriculture. One of the first domesticated animals, they provided man with food, clothing and shelter, and man providing the sheep with protection from predators. Over centuries, sheep were bred by men to have long white wool that was first cut off with Iron Age shears. Most domesticated varieties don't have horns.

Mouflon

Moufflon are a kind of wild sheep still found in remote parts of Europe and Western Asia. They are small and have long legs. Both the ram and ewe have heavy ringed horns and develop a wooly undercoat in the winter and shed it in the summer. Wild moufloun still live in the mountains of Corsica and Sardinia. In the 1970s, an Asian mouflon was born to a domestic wool sheep.

Mouflon (Ovis gmelini) are the smallest wild sheep. Regarded as the ancestors of domesticated and resembling goats more than sheep, they are 1.1 to 1.3 meters (3.6 to 4.3 feet) in length, with a seven to 12 centimeter tail (2.7 to 4.7 inch) and weigh 25 to 55 kilograms (55 to 122 pounds). They have relatively long legs. Their coat is red-brown with a dark central back stripes, flanked by a paler “saddle” patch. Males are horned; some females have horns, while others are polled. The curved horns of males reaches 85 centimeters (2.7 feet) in length.

Mouflon are native to Cyprus, and the Caspian region, including eastern Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Iran and also found in a few parts of Europe. They live in uplands and shrubby, grassy plains. Their normal habitats are steep mountainous woods near tree lines. In winter, they migrate to lower altitudes.

The scientific classification of the mouflon is disputed. The mouflon group (Ovis orientalis orientalis) is a subspecies group of the wild sheep (Ovis orientalis). Populations of O. orientalis can be divided into the mouflons (orientalis group) and the urials (vignei group). Mouflon have short-haired coats. The horns of mature rams are curved in almost one full revolution. Mouflon have shoulder heights of about 0.9 meters and body weights of 50 kilograms (males) and 35 kilograms (females). [Source: Wikipedia +]

See Separate Article: MOUFLON: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com ; WILD GOATS AND SHEEP OF CENTRAL ASIA factsanddetails.com

14,500-Year-Old Wild Sheep Remains Found in Jordan

moufflon, regarded as the wild ancestor of sheepIn 2017 paper published in Royal Society's journal Open Science and titled “Expansion of the known distribution of Asiatic mouflon (Ovis orientalis) in the Late Pleistocene of the Southern Levant”, the University of Copenhagen reported in the the Royal Society journal Open Science: Excavations of architecture and associated deposits left by hunter-gatherers in the Black Desert in eastern Jordan have revealed bones from wild sheep — a species previously not identified in this area in the Late Pleistocene. The discovery is further evidence that the region often seen as a 'marginal zone' was capable of supporting a variety of resources, including a population of wild sheep, 14,500 years ago. [Source: University of Copenhagen, Faculty of Humanities, August 22, 2017]

"On the basis of morphological and metrical analysis of the faunal remains from Natufian and Pre-Pottery Neolithic A hunter-gatherer deposits, we can document that wild sheep would have inhabited the local environment year-round and formed an important resource for the human population to target for food. Most significantly, however, the presence of the substantial number of bones identified as mouflon extends the known range of wild sheep. This means that we cannot rely on broad scale maps showing ancient wild animal distributions as neat lines," said zooarchaeologist and first-author of the study Lisa Yeomans of the University of Copenhagen.

The team have been investigating human occupation in the Late Pleistocene of eastern Jordan. The Levant (i.e. modern-day Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and Syria) has long been recognised as an important region associated with changes in social complexity and shifts in subsistence economy that pre-empted the shift to agriculture and farming. Hitherto investigations have generally focused on the Natufian occupation in the Levantine corridor while eastern Jordan was considered a more marginal environment.

Sheep Behavior

Sheep are motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). They sense using touch and chemicals usually detected with smell. [Source: Chris Reavill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

In contrast to unpredictable, frisky and "capricious" goats, sheep have a reputation of being docile, timid and vulnerable. They are easily taken by wild animals such as wolves and thus need the protection of man. Sheep live in flocks, sometimes following a leader, usually an old ram. They feed on grass, need pastures within distances that they can travel but are capable of ranging over a large area. They live in both very hot and very cold places and thrive in high and dry climates because they evolved from animals that live in high and dry climates.

Sheep have highly developed flocking or herding instinct. Large groups of sheep (up to 1000 or more) move over an area in groups, rather than as individuals. Often No "leaders" in the flock initiate grazing or other forms of behavior, including flight. This flocking instinct contributes to their economic significance as a single shepherd can control a large flock of animals. Sheep become considerably stressed when separated from others, often calling and pawing at the ground. /=\

Sheep are known for being dumb. They have been observed going into a panic by the sound of rustling paper, and often freeze to death in storms and drown while crossing streams. Entire flocks have been burned to death in farm houses because they too afraid to leave the burning building But maybe they are not as dumb as people think. Studies have shown that sheep recognize individual faces (50 sheep faces and 10 human ones) and still know them two years later. Studies also show familiar faces calm sheep and sheep can distinguish both happy and angry expressions, preferring the latter.

Sheep are social animals. One of the easiest ways to calm down agitated sheep is to show them photographs of other sheep. To prove the latter point sheep where placed in a dark place while things such as their heart rate, blood count and rate of bleating were measured to gage the levels of stress they felt. Those that were shown photographs of other sheep displayed lower levels of stress than those who were shown images of goats or triangles.

Sheep Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

The mating of sheep usually occurs in the early morning or in the evening. Rams search for ewes and if a ram suspects the ewe is in estrus, he will nudge the ewe in the perineum. The ewe then assumes a mating stance if interested in the ram or walk away if not. If the ewe is interested the ram will conduct a short "foreplay" session, mount and copulate. If not then he will move on to another ewe. Source: Chris Reavill, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The number of offspring ranges from one to two, with the average number of offspring being 1.3, The average gestation period is 5.03 months. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at one a half years. On average males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two and half years. /=\

Sheep breeds on a seasonal basis, determined by day length, with females (ewes) first becoming fertile in the early fall and remaining fertile through midwinter. Estrus cycles range between 14 and 20 days with 17 as the average. Females are in heat on average for 30 hours. Males (rams) are fertile year round and most domestic sheep breeders use one ram to 25 to 35 ewes. Most lambs born in mid spring. One or two lambs, which are able to stand and suckle within a few minutes of birth, are born to each ewe.

Male sheep sometimes show homosexual behavior. Studies show that about 8 percent of domestic rams prefer males as sexual partners. Other studies have show that the brains of homosexual sheep and their heterosexual counterpart were different. One study showed that groups of brain cells that controlled sexual behavior were smaller among ewes and males that preferred males than among males that preferred females

Dolly, the First Cloned Sheep

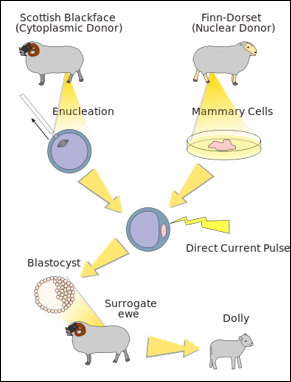

Dolly cloning A scientific advancement that caught everyone by surprise and happened much earlier than anyone anticipated was the cloning of a sheep named Dolly by the Scottish embryologist Ian Wilmut of Scotland's Roslin Institute. Other animals like frogs and pigs had been cloned before. What made Wilmut's advancement so revolutionary was that Dolly was produced from cells taken from an adult sheep (previous clones of advanced animals were made from fetal cells which are far easier to work with).

Dolly was an exact copy of her mother. Wilmut named her after the country singer Dolly Parton because she was produced cells taken from her pregnant mother's mammary gland (breasts). Explaining why he chose the name, Wilmut said, "No one could think of a more impressive set of mammary glands than Dolly Parton's.”

The cloning of Dolly was announced in February, 1997. Wilmut said he developed the process as a tool in animal husbandry not as a way to clone Bill Gates or Michael Jordans. In May 1997, the Roslin Institute applied for a patent on the Dolly cloning process. A sweater made from some of Dolly's wool was displayed at London Science Museum. Dolly died in 2003 at the age of six after being given a lethal injection when it was discovered that she had a progressive lung disease.

Dolly Cloning Procedure

The cloning of Dolly was achieved by reprogramming one cell (i.e. a bone, nerve or tissue cell) to perform the role of another kind of cell (a developing embryo cell) — a process thought to be impossible or so unlikely that most scientist who had tied it gave up on the idea. In the case of Dolly a donor cell was used with an egg that has been striped of its nucleus and stimulated with an electric pulse. Wilmut was able to fuse the adult DNA with the egg cell making the egg cell "quiescent" or inactive thus making the DNA more likely to be "read" and accepted.

It was previously though it would be impossible for he DNA of adult cells to act like the DNA in sperm and ovum cells. Wilmut took the cells from the mammary gland and prepared them so they would be accepted by an egg from another sheep, then replaced the egg DNA egg with the mammary gland DNA, which was fused with the egg cell. The fused cells to Wilmut's astonishment began to divided and replicate as if they were normal fetal cells to produce an embryo, which was then implanted in another ewe.

A year after Wilmut's great achievement scientists had not been able to duplicate the results. It took Wilmut's team 400 tries to create Dolly and even they were unable to create another sheep cloned from adult cells. Wilmut said there was a one in a million chance that his mammary gland cells could have been contaminated with fetal cells and suggests that they simply got lucky with Dolly and process is more difficult that previously thought.

In 1999, reports came out that Dolly had genetic aberrations that seemed to indicated that her cells were older than the cells of a normal sheep her age. Her cells contain slightly-stunted telomeres, appendages on chromosomes that indicate how many times a cell can divide before it dies. Older animals usually have shorter telomeres than younger animals.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Mostly National Geographic articles. Also Time, Newsweek, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Wikipedia, The Independent, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025