CHICKENS

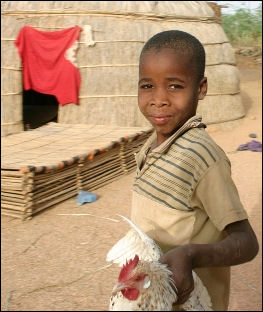

boy with chicken in Niger Chickens have traditionally been valued by villagers because they are an important source of meat and protein and they scavenge for food on their own and cost next to nothing to raise. A male chicken is called a cock or rooster. A female is called a hen. Young are called chicks. A group is called a flock.

Chickens were raised in Egypt and China for meat and eggs by 1400 B.C. Greeks ate them and they were in Britain at the time the Romans arrived. They were brought to New World by explorers and conquistadors.

Poultry are kept for eggs and meat. They require little care and can be sold if necessary for some cash to tide a family over until crops are ready. Egg and chicken meat production has increased over the years. In the 1920 hens laid about 120 eggs a year and it took 16 weeks to raise a two pound meat bird. Today hens lay 300 eggs or more a year a and four pound meat bird can be raised in four weeks.

Chicken is the most commonly eaten meat in America. Globally, it’s second behind pork, but it’s catching up fast. Perhaps soon, humans will eat more chicken than any other meat. Globally, more than 65.8 billion chickens are eaten every year. Modern chickens raised for food typically live between 33 and 81 days, [Sources: Allison Robicelli, Takeout, June 11, 2021; Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019; [Source NPR, 2015]

See Separate Article: CHICKEN INDUSTRY factsanddetails.com

Domestication of Chickens from Jungle Fowl

jungle fowl, Gallus sonneratii Chickens were first domesticated from the red jungle cock, a bird native to Thailand, Burma, Laos, eastern India and Sumatra, about 5,000 years ago, apparently as much for the production of fighting cocks as meat and eggs. Male jungle cocks look just like conventional roosters.

Jungle fowl are ground-dwelling birds. They spend most of their time searching for food by kicking their feet backwards and seeing what fruit, seeds and insects turn up. "Jungle fowl roosters cry “cock-a-doodle-doo” to herald the sunrise. Their cock a doodle do is a high pitched, slightly strangulated version of the crow that modern roosters produce. Jungle fowl chicks sometimes have coloring similar to chipmunks, which is ideal camouflage.

Some have speculated that people may have first kept chickens for this symbolic connection with the dawn. In ancient India priests sacrificed chickens to the god of the sun. Other early Asian societies bred the birds for cockfighting.

The jungle fowl adapted easily to domestication. They became a dual-purpose bird. They produced eggs. When the bird grew to old to lay they could be killed for their meat. And of course they also provided cocks for fighting.

See Separate Article: JUNGLE FOWL (CHICKENS) factsanddetails.com

Chicken Characteristics and Behavior

Chickens belong to the same family of birds as quails, partridges and pheasants. They are the only birds with combs, the fleshy growth on their heads; they generally eat seeds, insects and worms; and can fly several meters to make an escape. An average rooster weighs around 7 pounds, an average hen, 5 pounds.

There are 180 varieties of the 50 standard poultry breeds. White Leghorns are considered the best egg-laying variety. Poultry chickens usually only live for about three weeks before they are slaughtered.

Females usually select males with the largest combs and wattles to mate with. Jungle fowl attacked by round worms usually have smaller combs and wattles that non-infected birds and consequently have a hard time getting a mate. Red combs of roosters contain relatively large amounts of the sugar molecule hylauronan, which some predict will be the next botox-like anti-wrinkle agent.

Females have a defined pecking order, which determines who eats and drinks first. Males control harem-like flocks, which they jealously defend. A rooster show his interests in a hen by spreading his wings and helping her find a nesting site. Chicks break out their shells after 21 days and are up around in a few hours.

When chickens see blood or even red they peck. To keep chickens from pecking each other to death scientists have experimented with outfitting chickens with red contact lenses so they don't see red.

Ancient Avian Bones Found in China: Oldest Example of Chicken Domestication?

Jungle fowl In November 2014, a team of researchers in China studying ancient avian bones found in the northern part of that country, said there were indication they may be that of the oldest known example of chicken domestication. The scientists described their analysis and findings in a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers [Source: Bob Yirka, phys.org, November 25, 2014 ^^^]

Bob Yirka wrote in phys.org: “Identifying the first culture to domesticate chickens has been hotly debated for over a century, without any clear winner, and it may remain that way as evidence is piling up suggesting that chickens were likely domesticated in a variety of places across the globe and have since undergone comingling, creating a mish-mash of genetic evidence. In this new effort, the researchers sought to find out if ancient bone samples found in four different archeological sites in northern China were chicken ancestors and if so, if they were domesticated. The bones were found alongside charcoal and other animal remains, such as dogs and pigs, both of which are believed to have been domesticated by that time in history, suggesting that the bird bones were from a species that had been domesticated as well. The excavation sites have also given up other findings which suggest the people who’d been barbecuing the animals were farmers, not hunters, which also adds credence to the idea that the birds they were eating were domesticated. ^^^

“The bones in question (39 in all) had been previously carbon dated to various ages, ranging from 2,300 to 10,500 years ago. The new research focused on gathering genetic evidence and using mitochondrial DNA sequencing to determine if the birds were chicken ancestors, or not. The team compared the DNA of the ancient birds with modern birds of the Galliformes order, which include rock partridges, pheasants and of course chickens and also to samples of ancient bones found in other places, such as Spain, Hawaii, Easter Island and Chile. Their analyses revealed that the birds were members of the genus Gallus, which includes modern chickens. But it’s still not enough to prove that they were actually the first example of domesticated chickens because there is still no conclusive proof that the birds were actually domesticated.”

See Separate Article FIRST CROPS AND EARLY AGRICULTURE AND DOMESTICATED ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Were Chickens First Domesticated as a Food Source in Israel?

Some of the earliest evidence of chickens being consumed as food in the West comes from Maresha, an ancient, abandoned city in Israel that flourished in the Hellenistic period from 400 to 200 B.C.. “The site is located on a trade route between Jerusalem and Egypt,” says Lee Perry-Gal, a doctoral student in the department of archaeology at the University of Haifa. As a result, it was a meeting place of cultures, “like New York City,” she says. [Source: Daniel Charles, NPR, July 20, 2015]

According to Archaeology magazine: The Hellenistic site of Maresha, might be where chickens became chicken. Jungle fowl had been domesticated millennia earlier in Asia and had already spread across Europe, but in small numbers, usually as fighting cocks or for ritual purposes. But at Maresha there are thousands of chicken bones, which tells researchers that the site is key to understanding how the birds came to be regarded as food and bred in large numbers a hundred years before the chicken-chomping craze swept across Europe. [Source: Samir S. Patel Archaeology magazine, November-December 2015]

Daniel Charles of NPR wrote: “The surprising thing was not that chickens lived here. There’s evidence that humans have kept chickens around for thousands of years, starting in Southeast Asia and China. But those older sites contained just a few scattered chicken bones. People were raising those chickens for cockfighting, or for special ceremonies. The birds apparently weren’t considered much of a food. In Maresha, though, something changed. The site contained more than a thousand chicken bones. “They were very, very well-preserved,” says Perry-Gal, whose findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Perry-Gal could see knife marks on them from butchering. There were twice as many bones from female birds as male. These chickens apparently were being raised for their meat, not for cockfighting.

Perry-Gal says there could be a couple of reasons why the people of Maresha decided to eat chickens. Maybe, in the dry Mediterranean climate, people learned better how to raise large numbers of chickens in captivity. Maybe the chickens evolved, physically, and became more attractive as food. But Perry-Gal thinks that part of it must have been a shift in the way people thought about food. “This is a matter of culture,” she says. “You have to decide that you are eating chicken from now on.”

In the history of human cuisine, Maresha may mark a turning point. Barely a century later, the Romans starting spreading the chicken-eating habit across their empire. “From this point on, we see chicken everywhere in Europe,” Perry-Gal says. “We see a bigger and bigger percent of chicken. It’s like a new cellphone. We see it everywhere.”

People in Bulgaria’s Ate Domesticated Chickens 8,000 Years Ago

Ivan Dikov wrote in Archaeologyinbulgaria: “The prehistoric people inhabiting the Early Neolithic settlement near today’s town of Yabalkovo in southern Bulgaria, had domesticated hens some 8,000 years ago, meaning that chickens were raised in Europe much earlier than previously thought, Bulgarian archaeologist Assoc. Prof. Krasimir Leshtakov revealed. Leshtakov, who is a professor of archaeology and prehistory in Sofia University excavated the Neolithic proto-city, which dates back to the 7th millennium B.C., between 2000 and 2012. The settlement near Yabalkovo was first discovered by Bulgarian paleo-ornithologist Prof. Zlatozar Boev from the National Museum of Natural History in Sofia who found bones from domesticated birds there, and was then excavated by archaeologists. [Source: Ivan Dikov, Archaeologyinbulgaria =||=]

“Until recently it had been thought that domesticated chickens became widespread in Europe only after the Arab invasions in the Early Middle Ages (even though there is evidence that domesticated chickens were also known but not widespread in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome). However, some 8,000 years ago, the prehistoric people at Yabalkovo produced a breed of larger broody hens which could not fly, as indicated by the bones of four broody hens found there Leshtakov has also explained that the Early Neolithic proto-city near Bulgaria’s Yabalkovo is the largest one of its kind in the Balkan Peninsula. Its civilization first came from Anatolia in today’s Turkey, settled the plain around today’s city of Haskovo as well as the Eastern Rhodope Mountains, and probably numbered several tens of thousands which is a fairly large number for that time period. =||=

“Based on his findings, the Bulgarian archaeologist says that in addition to chickens the prehistoric people of Yabalkovo also had domestic pigs, alcohol, white and yellow cheese (called kashkaval in Bulgaria), and raised large herds of goats, sheep, and cattle. These Early Neolithic people also smelted copper which is the earliest case of metallurgy in Europe. Another interesting topic explored in Leshtakov‘s book is connected with the fact that the DNA of the Neolithic inhabitants of the region of Haskovo loosely matches the DNA of today’s residents of the same region, which is taken to mean that the genetic heritage of the prehistoric people who lived there 8,000 years ago is greater than previously imagined. =||=

“The Early Neolithic proto-city near Yabalkovo was first found by Bulgarian paleo-ornithologist Zlatozar Boev after he discovered there bones from 5 domesticated bird species: mute swan (Cygnus olor), two undetermined species resembling geese from the Anser genus, Eurasian coot (Fulica atra), and the bones of four domesticated hens (Gallus gallus f. domestica) which were selected by the prehistoric people to produce a breed of larger broody hens that could not fly. Thus, the Early Neolithic settlement near Bulgaria’s Yabalkovo is the earliest known case of the raising of domestic chickens in Europe. The excavations have also revealed a lot of bones from domesticated livestock such as pigs, goats, sheep, and cattle, and few bones of wild herbivores meaning the Early Neolithic people from Yabalkovo were agriculturalists who did little hunting. Only 3% of their meat is estimated to have come from hunting. They were picky about their rich diet as 75% of the discovered animal bones are from young animals. As indicated by the fish bones and snail shells, they also fished for 10-kilogram carps in the nearby Maritsa River, ate snails (a total of 900 snail shells have been found in a pit on the site). They also grew pistachios, made their bread of spelt (dinkel wheat or hulled wheat, Triticum spelta), and had wine. They also had beer made of sour apples (interestingly, the name of today’s town of Yabalkovo comes from “yabalka”, the Bulgarian word for apple), and probably used formic acid for the beer’s fermentation.” =||=

Evolution of Chickens as a Food Source

Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: A group of scholars from the United Kingdom and South Africa have compared the size of chickens over time from Roman Britain to the present day. The results show that chickens gradually increased in size for almost 2,000 years until about 1950, when broiler chickens — those raised to provide meat rather than eggs — started to get huge. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, March-April 2019]

Compared with the Asian red jungle fowl, from which they have evolved, modern broilers are positively gargantuan. At the time of slaughter, they can be twice the weight of their Asian forebears. The researchers attribute this rapid size expansion to a breeding program called “Chicken of Tomorrow” that was launched in the midtwentieth century by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in partnership with private business. The program’s goal was to increase meat production. Today, billions of chickens are eaten each year by the world’s growing human population. All these chickens’ skeletons end up in landfills, a prime location to wait out the millennia for future excavators.

Were Ancient Chickens Were Too Sacred to Eat?

In ancient times chickens often lived past two years of age — compared to one or two months for modern, industrially-raised chickens, in part because they were regarded as sacred, some scholars have argued. Researchers at the University of Exeter developed a way to examine 3,000-year-old bones that reveal the age at which ancient chickens died. They examined poultry bones from Britain’s Iron Age and Roman and Saxon period and found these chickens lived between two and four years. The researchers believe the chickens they analyzed were used for ritual sacrifices or cockfighting. [Source: Allison Robicelli, Takeout, June 11, 2021]

According to The Takeout: “This discovery is exciting for archaeologists and chicken-history buffs, because most existing bone dating techniques — such as analyzing fusion and tooth wear — cannot be used on birds’ delicate skeletons. To crack the chicken code, the Exeter researchers had to develop a brand new bone dating method based on size of the tarsometatarsal spur, a leg joint that male chickens develop once they reach adulthood. The researchers analyzed 123 ancient chicken bones and were able to determine that 50 percent belonged to chickens that had lived past the age of two, and 25 percent made it past three.

“According to Dr. Sean Doherty, the archaeologist who led the study, the findings imply that these chickens were revered by the native tribes of prehistoric Britain. ”Most chicken bones show no evidence for butchery and were buried as complete skeletons rather than with other food waste,” said Doherty in an article published on the University of Exeter’s website. ”The study confirms the special status of these rare and highly prized birds, showing that from the Iron Age to Saxon period they were surviving well past sexual maturity. Most lived beyond a year, with many reaching the age of two, three and four years old. The age of which cockerels then started to die at becomes younger after this period.”

Did Medieval Christianity Play a Role in Chicken Domestication?

Religious beliefs in the Middle Ages helped create the modern domestic chicken, researchers say. Scientists found traits such as reduced aggression, faster egg-laying and an ability to live in close proximity to other birds emerged in chickens in about A.D. 1000 and this occurred because what people ate was strongly influenced by Christian beliefs. [Source: news.com.au, May 17, 2017]

AAP reported: During the Middle Ages, religious edicts enforced fasting and the exclusion of four-legged animals from menus. However, the consumption of chickens and eggs was permitted during fasts. Increasing urbanisation might have helped drive the evolution of modern domesticated chickens, the study, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, said. “Ancient DNA allows us to observe how genes have changed in the past, but the problem has always been to get high enough time resolution to link genetic evolution to potential causes,” Oxford University lead researcher Dr Liisa Loog said. “But with enough data and a novel statistical framework, we now have timings that are precise enough to correlate them with ecological and cultural shifts.”

Chickens were domesticated from Asian jungle fowl around 6000 years ago. But the new study, which combined DNA data from archaeological chicken bones with statistical modelling, showed some of the most important features of the present-day chicken arose in the high Middle Ages during a time of soaring demand for poultry. They traced the evolutionary history of more than 70 chickens, looking for changes in the THSR gene that determines levels of aggression. Natural selection favoured chickens with THSR variants that helped them cope with living close to one another, the study found. THSR variants also led to faster egg laying and a reduced fear of humans.

A thousand years ago, just 40 per cent of the chickens studied had this gene, which is present in all modern domesticated chickens. “We tend to think that there were wild animals and then there were domestic animals rather than thinking about the selection pressures on domestic plants and animals that varied through time,” Dr Loog said. “This study shows how easy it is to turn a trait into something that becomes fixed in an animal in an evolutionary blink of an eye.”

Chicken Industry

chicken in Malaysia Industrially-raised broiler chickens live for eight weeks and have their beaks cut of with a hot knife so they don’t peck and cannibalize one other. Chicken feed in the United States often contains fish meal from Asia. The use of antibiotics is high in the chicken industry.

Chickens are often slaughtered before their chest muscles are fully developed. The result is less tasty “PSE”—“pale, soft, exudative” — meat. Scientists have developed a breed of featherless chickens, known as naked chicken, that save producers the cost of removing the feathers and have less fat the other chickens.

Industrially-raised egg-laying chickens are packed together indoors with about a half dozen other birds in cages so small the chickens cannot extend their wings and the floor is only large enough for a page of a magazine to cover. Some try to cannibalize one another. Others rub they themselves against their cages until their feathers fall out and their skin bleeds. About 10 percent die. Those that survive are deprived of food and water to get them to lay larger eggs and starved before they die to induce one last bout of stress-induced egg-laying.

In the late 2000s, cage-free chickens and cage-free hens became all the rage in the United States. Sometimes the term “free-range” is used instead of “cage-free.” The term “free range” can be misleading though. Many free range chickens never see the light of day as the sheds they live are often too crowded for them to make their way to opening to get outside.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024