CORN AND MAIZE

Corn is the world’s No.1 grain in terms of production but only No.3 as dietary staple after rice and wheat, accounting for 5 percent of the world’s human caloric intake. The reason for this discrepancy is that most corn is raised primarily as livestock feed. There are over 300 different "races" of corn. In most parts of the world corn is called maize. [Source: Robert Rhoades, National Geographic, June 1993, ╖]

Corn kernels are the main source of food. They are wrapped in a tough, fibrous outer hull which makes up about 3 percent of the kernel. The germ makes up 4.5 percent. The remainder is the endosperm. Corn kernels contains about 10 to 25 percent water depending on the conditions it is grown. Of the dry portion about 10 percent is protein, 10 percent is fiber, minerals and fat and 80 percent is carbohydrates. The protein, called gluten, is nutritious and provides a stickiness useful in trapping yeast and making bread. Most of the carbohydrates are in the form of starch.

Corn crops yield canned corn, corn on the cob, corn oil, corn meal, breakfast cereals, corn sugar, corn syrup alcohol for whiskeys, margarine, livestock feed, fibers used in inks and lacquers, and starch used in paper and textile manufacturing and numerous other products. Scientists are now experimenting with other uses for corn such as corn starch packing peanuts and biodegradable corn-based golf tees. Corn can be made into sugar-based ethanol which can be mixed with gasoline.╖

Over half of the world's corn supply is grown in the United States, where surprisingly only 1.4 percent of it ends up on the dinner table eaten as whole kernel or processed corn. Most of it is used as animal feed. In 2006, corn prices were very high. The high prices were attributed to high oil prices and increased demand for corn to make ethanol and increased demand from China. Some worry that demand for ethanol will mean less food and more starving people.

Overall, very little corn is consumed on the cob or even is cans or frozen packets. Much of the corn in the United States is grown for animal feed and corn syrup and corn sugar for processed foods. Most corn that is produced is worldwide is used for livestock feed. In many parts of the world where it is eaten by humans it is ground into flour and consumed as bread, tortillas or porridge.

Websites and Resources: University of Iowa Corn Page agronext.iastate.edu ; National Corn Growers Association ncga.com ; Corn Growers Guidebook agry.purdue.edu ; History of Corn New York Times ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;U.S. Grains Council grains.org/corn ; International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center cimmyt.org ;

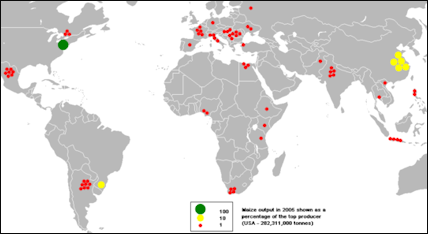

World’s Top Maize (Corn) Producing Countries

World’s Top Producers of Maize (Corn) (2020): 1) United States: 360251560 tonnes; 2) China: 260670000 tonnes; 3) Brazil: 103963620 tonnes; 4) Argentina: 58395811 tonnes; 5) Ukraine: 30290340 tonnes; 6) India: 30160000 tonnes; 7) Mexico: 27424528 tonnes; 8) Indonesia: 22500000 tonnes; 9) South Africa: 15300000 tonnes; 10) Russia: 13879210 tonnes; 11) Canada: 13563400 tonnes; 12) France: 13419140 tonnes; 13) Nigeria: 12000000 tonnes; 14) Romania: 10942350 tonnes; 15) Ethiopia: 10022286 tonnes; 16) Pakistan: 8464885 tonnes; 17) Hungary: 8365430 tonnes; 18) Philippines: 8118546 tonnes; 19) Serbia: 7872607 tonnes; 20) Egypt: 7500000 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org. A tonne (or metric ton) is a metric unit of mass equivalent to 1,000 kilograms (kgs) or 2,204.6 pounds (lbs). A ton is an imperial unit of mass equivalent to 1,016.047 kg or 2,240 lbs.]

World’s Top Producers (in terms of value) of Maize (Corn) (2019); 1) United States: Int.$69663519,000 ; 2) China: Int.$52346645,000 ; 3) Brazil: Int.$20301747,000 ; 4) Argentina: Int.$11413757,000 ; 5) Ukraine: Int.$7202271,000 ; 6) Indonesia: Int.$6161136,000 ; 7) India: Int.$5563305,000 ; 8) Mexico: Int.$5465577,000 ; 9) Romania: Int.$3499203,000 ; 10) Russia: Int.$2866924,000 ; 11) Canada: Int.$2690590,000 ; 12) France: Int.$2578405,000 ; 13) South Africa: Int.$2263353,000 ; 14) Nigeria: Int.$2208051,000 ; 15) Ethiopia: Int.$1934199,000 ; 16) Hungary: Int.$1651961,000 ; 17) Philippines: Int.$1601609,000 ; 18) Egypt: Int.$1495453,000 ; 19) Serbia: Int.$1474284,000 ; [An international dollar (Int.$) buys a comparable amount of goods in the cited country that a U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.]

top maize producers Top maize-producing countries in 2008: (first, Production, $1000; second, production in metric tons. FAO): 1) United States of America, 20261250 , 307142010; 2) China, 6959063 , 166032097; 3) Argentina, 2042438 , 22016926; 4) Brazil, 1925338 , 58933347; 5) India, 1442042 , 19730000; 6) Mexico, 1292539 , 24320100; 7) Indonesia, 1286208 , 16323922; 8) South Africa, 1004019 , 12700000; 9) France, 908509 , 15818500; 10) Nigeria, 688353 , 7525000; 11) Hungary, 685763 , 8897138; 12) Canada, 451757 , 10592000; 13) Ethiopia, 424389 , 3776440; 14) United Republic of Tanzania, 392414 , 3659000; 15) Ukraine, 357746 , 11446800; 16) Pakistan, 311997 , 3593000; 17) Philippines, 275573 , 6928220; 18) Kenya, 259502 , 2367237; 19) Malawi, 255983 , 2634701; 20) Romania, 247997 , 7849080;

History of Corn

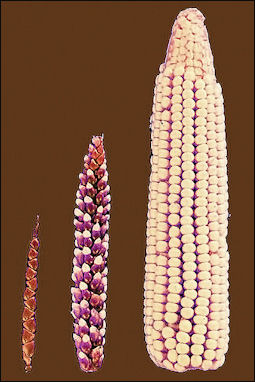

Some scientists believe that the corn from teosinte a weedy wild grass still found in remote areas of Mexico that has inch-long "ears" and look more like wheat than corn. Other believe it comes from criollo, a plant native to a remote region of Sierre Norte de Oaxaca in Mexico, or cornlike plant that has since become extinct. Primitive corncobs from these plants found in a Oaxaca cave were dated to 6,300 B.C.

In 2001, based of DNA studies, scientists concluded that corn did in fact evolve from teosinte. It is believed that ancient people in southern Mexico and Central America began harvesting grains from wild teosinte about 10,000 years. Through selective breeding these plants developed large stalks and seeds and eventually these became the cobs we associate with corn today.

People in the New World ate a variety of corn products. The Mayans drank “atole” , a thick beverage made from fermented corn meal. Popcorn was invented in Peru. In 1493 Columbus carried corn from the New World back to Spain. At first it was treated as a novelty by botanists, but within a hundred years it was widely grown not only in Europe but also in Africa and Asia.

Indian corn came in a variety of colors. Europeans preferred the yellow variety. Over time scientists created hybrids with desirable characteristics that resulted in the corns were are familiar with today. Some were bred for eating. Others were bred to produce large quantities of food. New varieties of corn were one of the cornerstones for the Green Revolution in the 1970s. But unfortunately the drive to create a few high-yield species has caused many other varieties to disappear. Only 20 percent of the corn recorded in Mexico in 1930 can be found today.

First Corn

Most scientists believe that corn (maize) originated from teosinte a weedy wild grass still found in remote areas of Mexico that has inch-long "ears" and look more like wheat than corn. Some scientists believe it comes from criollo, a plant native to a remote region of Sierre Norte de Oaxaca in Mexico, or cornlike plant that has since become extinct. Primitive corncobs from these plants found in a Oaxaca cave were dated to 6,300 B.C. In 2001, based of DNA studies, scientists concluded that corn did in fact evolve from teosinte. It is believed that ancient people in southern Mexico and Central America began harvesting grains from wild teosinte about 10,000 years ago. Through selective breeding these plants developed large stalks and seeds and eventually these became the cobs we associate with corn today.

Jessica Boddy wrote in Science: ““The first glimpses of maize domestication came in the 1960s, when esteemed U.S. archaeologist Richard MacNeish excavated at caves in Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley, a center of early Mesoamerican agriculture. In the dry, dark environment there, he found tiny, well-preserved maize cobs dated to roughly 5300 years ago and harboring only 50 kernels each, compared with the 1000 on modern cobs.” [Source: Jessica Boddy, Science, November 21, 2016]

teosinte on the left Most historians believe corn was domesticated in the Tehuacán Valley of Mexico or the the adjacent Balsas River Valley of south-central Mexico An influential 2002 study by Matsuoka et al. demonstrated that, rather than the multiple independent domestications model, all maize arose from a single domestication in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago. The study also demonstrated that the oldest surviving maize types are those of the Mexican highlands. Later, maize spread from this region over the Americas along two major paths. This is consistent with a model based on the archaeological record suggesting that maize diversified in the highlands of Mexico before spreading to the lowlands. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Archaeologist Dolores Piperno said: “A large corpus of data indicates that it [maize] was dispersed into lower Central America by 7600 BP [5600 BC] and had moved into the inter-Andean valleys of Colombia between 7000 and 6000 BP [5000–4000 BC]. [Source: Dolores Piperno, “The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments”]

Since then, even earlier dates have been published.According to a genetic study by Embrapa, corn cultivation was introduced in South America from Mexico, in two great waves: the first, more than 6000 years ago, spread through the Andes. Evidence of cultivation in Peru has been found dating to about 6700 years ago.The second wave, about 2000 years ago, through the lowlands of South America. +

Before domestication, maize plants grew only small, 25 millimetres (1 in) long corn cobs, and only one per plant. In Spielvogel's view, many centuries of artificial selection (rather than the current view that maize was exploited by interplanting with teosinte) by the indigenous people of the Americas resulted in the development of maize plants capable of growing several cobs per plant, which were usually several centimetres/inches long each. The Olmec and Maya cultivated maize in numerous varieties throughout Mesoamerica; they cooked, ground and processed it through nixtamalization. It was believed that beginning about 2500 BC, the crop spread through much of the Americas.

5000-Year-Old Cobs Show Corn Domestication

Jessica Boddy wrote in Science: “It wasn’t easy to make a meal of teosinte, a grass that was the ancient precursor to maize. Each cob was shorter than your little finger and harbored only about 12 kernels encased in rock-hard sheaths. But in a dramatic example of the power of domestication, beginning some 9000 years ago people in Mexico and the U.S. Southwest transformed teosinte into the many-kerneled maize that today feeds hundreds of millions around the world. Researchers had already identified a handful of genes involved in this transformation. Now, studies of ancient DNA by two independent research groups show what was happening to the plant’s genes mid-domestication, about 5000 years ago. The snapshot reveals exactly how the genetics changed over time as generations of people selected plants with their preferred traits. “These results sharpen the focus of what we know at this early period,” says Michael Blake, an anthropologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, who was not involved in the work. “They have implications for understanding later developments in maize domestication and help us to see what people were selecting for at the time.” [Source: Jessica Boddy, Science, November 21, 2016 ++/]

“After the advent of modern sequencing tools, geneticist Jean Philippe Vielle-Calzada at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies of the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity in Irapuato, Mexico, and his colleagues wanted to find out which genes the ancient domesticators had unwittingly been selecting. But he worried that MacNeish’s specimens, now in museums, might have been damaged by handling or improper storage. So he and his team decided to go back to the caves in Tehuacán Valley. Macneish had died, but one of his former students, Angel Garcia Cook, served as guide. “He had all the maps, he knew where to dig,” Vielle-Calzada says. “He went back with us at 73 years old. When he went the first time he was 21.” ++/

“The team discovered several new specimens, dated to about 5000 years ago, from San Marcos cave. They applied shotgun sequencing to three cobs, extracting DNA and breaking it up into short fragments for sequencing. Computer software then reassembled these DNA snippets, eventually reconstructing more than 35% of the ancient maize genome. ++/

teosinte in Oaxaca “Vielle-Calzada’s team identified eight genes influencing key traits, as they wrote in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week. The cobs carried the modern variants of tb1, which simplified the plant’s branching for easier harvest, and bt2, which helped boost the starch content and sweetness of the kernels. But the cobs had the teosinte variant of tga1, which encloses the kernels in those hard sheaths—a sign that domestication was only partial. ++/

“Meanwhile, archaeologist Nathan Wales of the University of Copenhagen and his colleagues discovered MacNeish’s original samples, stored for 60 years in a museum in Andover, Massachusetts. He and his colleagues shotgun sequenced the genome of a 5300-year-old cob called Tehuacan162. Wales’s team was able to sequence 21% of this cob’s genome. Their results confirmed and complemented those of Vielle-Calzada’s team. The museum cob also had modern variants of td1 and bt2, as reported in Current Biology last week. But Tehuacan162 also had a more modern variant of the gene tga1, which partly released kernels from their rigid shells, making them easier to eat. Wales’s team also found a teosinte gene not seen by the Mexican team: zagl1, which makes kernels fall from the cob very easily. That’s useful for wild plants spreading their seeds, but frustrating for humans trying to harvest them. These differences may reflect the fact that Tehuacan162 came from a different population of maize, and show that domestication was still in progress in the valley, the researchers say. ++/

“Vielle-Calzada was shocked at the teams’ similar results. “I’m really amazed to see how convergent the results are,” he says. “This is unusual in paleogenomics where it’s difficult to get good data from old DNA. This is encouraging.” Robert Hard, an archaeologist at the University of Texas in San Antonio, agrees: “It’s remarkable how these studies support each other,” he says. That’s a good sign that future sequencing can fill in more details, he says. “It’s really important that we recognize the significance of transformations in maize,” Blake says, adding that knowledge of how certain traits helped maize adapt to drought and disease in the past could help save it from disasters in the future.” ++/

Ancient Genomes Show How Maize Adapted to High Altitudes

A study published on August 3, 2017 in Science described how genome sequences from nearly 2,000-year-old cobs of maize (corn) found in a Utah cave provide insights into how the crop was able to adapt to the highlands of the U.S. southwest when its was first grown there thousands of years ago. According to an article in Nature: That maize, researchers found, was small, bushy and — crucially — had developed the genetic traits it needed to survive the short growing seasons of high altitudes. The team’s study is remarkable in how it tackles complex genetic traits governed by the interactions of many different genes, say researchers. It uses that information to create a detailed snapshot of a crop in the middle of domestication. Such insights could help modern plant breeders to buffer crops against global climate change. [Source: Nature, August 3, 2017]

Maize originated in Mexico and rapidly spread into the lowlands of the southwest United States about 4,000 years ago. But communities at higher altitudes did not fully embrace the crop until 2,000 years later — a delay that has long puzzled archaeologists studying the region, says Kelly Swarts, a quantitative geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, Germany. “There was always the question: why wasn’t this catching on? Why weren’t people doing agriculture in the uplands?” she says.

“Swarts and her colleagues turned to a site in a Utah cave called Turkey Pen Shelter, where a farming community lived about 2,000 years ago. Inhabitants of the cave raised turkeys, wove intricate baskets and shoes, and had the resources needed to store and process corn. Maize, which they probably served in soups and stews, comprised about 80 percent of their diet.

“Swarts’s team sequenced the genomes of fifteen 1,900-year-old maize cobs found in the shelter and compared their sequences to those in a database of genomes and physical traits from some 2,600 modern maize lines. The researchers then used that information to extrapolate the physical characteristics of the Turkey Pen maize plants, including complex traits such as flowering time. The analysis revealed a crop that was shorter and more branched than modern varieties. “More like little bushes,” says Swarts, though the role of these traits is unclear. The crop also flowered more quickly than lowland varieties — an important adaptation to life in the highlands, which have a shorter growing season than lower elevations.

“A key finding from the study, says Matthew Hufford, who studies evolutionary genomics in maize at Iowa State University in Ames, was the realization that the genetic variants needed to adapt to highland life were already circulating in maize populations thousands of years ago “The diversity needed for high altitudes was there, but getting it in the right combination took 2,000 years,” he says. And that diversity could be crucial for breeders as they try to adapt modern maize to a rapidly changing climate, says Swarts. “It’s really promising for maize’s future that it has so much standing variation — assuming we can conserve that diversity,” says Swarts. “If we needed to do this, it wouldn’t take 2,000 years. We could do it a lot faster now.”

Corn Agriculture

Mature corn plants can grow over 40 feet high but most are between six and 20 feet high. At the top of the plant is a spiked tassel. Further down are one of more spikes that develop into ears, which grow from the beneath the leaves. Certain agricultural techniques have been developed for specific varieties of corn. Great care has to be taken though not to injure the shallow grasslike roots.

Corn has many advantages over other grains. It can be harvested every 120 days and grows in a wide variety of habitats: rain forests with poor soils, deserts with 115̊F temperatures, 12,000-foot-high mountain terraces, and glacier scoured land near the Arctic.

Corn needs lots of sun; requires the clearing of land to cultivate; grows best in well drained soils; and often need a lot of water. Because corn requires more nutrients than some other grains it often is rotated in a three-year cycle when a enough fertilizer isn't available. Legume, alfalfa or sweet clover are planted the first year to provide enough nitrogen. The second year corn is grown. The following year a small grain is cultivated. Then the three-year cycle is repeated.

Most corn is harvested with mechanical pickers. The entire corn plant is often harvested and stored in a silo. After it has dried the grain is removed. The stalks and leaves are often used in livestock feed.

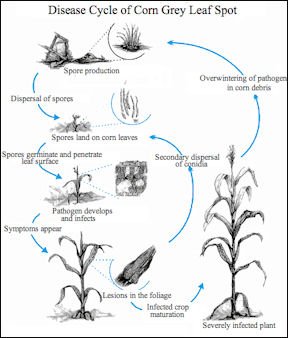

Corn is vulnerable to a number of pests and diseases. The corn crop in the United States the 1970s was devastated by an unusual fungus. the problem was remedied by modifying seeds s they contained a gene from the a type of African maize resistant to disease.

Corn Advances

New plant varieties and advances in technology have boosted corn yields by nearly 80 percent. The National Agricultural Research Organization of Uganda has developed corn varieties that do well in nitrogen-poor soil and are more resistant to disease. Not all the new varieties are perfect. Drought-resistance corns suffer in freak rains.

In Britain, biodegradable bottles made from corn are used in Belu bottled water. Ingeo, fabric made from corn, is biodegradable and has been used in hiking socks by Teko and chic fashions by NatureVsFuture.

Genetically-modified (GM) versions of corn are now widely used. Just two engineered traits are sold: 1) resistance to glyphosate, a herbicide used to kill weeds and crops; 2) use of BT, a microorganism that produces chemicals that are toxic to insects not humans.

There are worries that GM crops could spread unpredictably and that genetic diversity will be compromised. Local varieties of corn in Mexico have already been contaminated by GM varieties even though GM corn are banned in Mexico. Mexico approved the use of GM corn in 2008 on a limited basis but only after a buffer zone was set up to protect native species.

Corn Bioethanol

The main sources for biofuel at this time are palm oil, rapeseed (colza), sunflowers, sugar cane, corn, and jatropha. New processes that can turn woody, weedy plants like switch grass, poplar, wheat straw and corn stalks into cellulosic ethanol.

Biofuel sources (gallons per acre): 1) sugar beets (714); 2) sugar cane (662); 3) cassava (410); 4) sorghum (374); 5) corn (354).

There are two main kinds of ethanol: 1) corn ethanol derived from corn, sugar cane and soy beans; and 2) cellulosic ethanol derived from plants like switchgrass (summer grass) , wood chips, agricultural wastes such as stalks and leaves and husks, forest waste such as bark and sawdust, paper pulp and timber chip. The latter produces more energy than corn ethanol but takes more energy to manufacture.

Corn is made into ethanol by grinding the corn, mixing it with water and heating it. Enzymes are added that convert starch to sugar. Fermentation turns the sugar into alcohol, which is separated from the water by distillation. Waste solids are fed to livestock. Wastewater can be made into fertilizer. The biggest drawback with the process — especially if coal energy is used to provide heat for distillation — is that it produces a lot of carbon dioxide.

In 2007, about 25 percent of the total corn crop of the United States was used for biofuel. The demand for corn for biofuels helped boost corn prices to a record high of $288.10 per ton in June 2008. Corn isn’t the best biofuel crop . It requires large amounts of herbicides and nitrogen fertilizer and can cause soil erosion. Producing it requires about as much energy as is produced by the fuel. Corn-based ethanol produces carbon dioxide but about 15 percent less than gasoline.

World’s Top Maize (Corn) Exporting Countries

corn field World’s Top Exporters of Maize (Corn) (2020): 1) United States: 51838933 tonnes; 2) Argentina: 36881996 tonnes; 3) Brazil: 34431936 tonnes; 4) Ukraine: 27952483 tonnes; 5) Romania: 5651064 tonnes; 6) France: 4558720 tonnes; 7) Hungary: 4040502 tonnes; 8) Serbia: 3608208 tonnes; 9) South Africa: 2584946 tonnes; 10) Bulgaria: 2559570 tonnes; 11) Russia: 2289269 tonnes; 12) Paraguay: 2106920 tonnes; 13) India: 1766876 tonnes; 14) Poland: 1490378 tonnes; 15) Croatia: 1213051 tonnes; 16) Myanmar: 1191119 tonnes; 17) Canada: 1132480 tonnes; 18) Netherlands: 849256 tonnes; 19) Slovenia: 841207 tonnes; 20) Slovakia: 619203 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Maize (Corn) (2020): 1) United States: US$9575254,000; 2) Argentina: US$6046745,000; 3) Brazil: US$5853003,000; 4) Ukraine: US$4885125,000; 5) France: US$1711436,000; 6) Romania: US$1234562,000; 7) Hungary: US$997546,000; 8) Serbia: US$665307,000; 9) South Africa: US$566234,000; 10) Bulgaria: US$497072,000; 11) Russia: US$395244,000; 12) India: US$389280,000; 13) Myanmar: US$382695,000; 14) Paraguay: US$322343,000; 15) Poland: US$321528,000; 16) Austria: US$284794,000; 17) Canada: US$250141,000; 18) Netherlands: US$235694,000; 19) Croatia: US$226688,000; 20) Germany: US$155549,000

World’s Top Exporters of Maize (Corn), Green (2020): 1) United States: 62914 tonnes; 2) Spain: 59043 tonnes; 3) Mozambique: 22672 tonnes; 4) Morocco: 16923 tonnes; 5) France: 15662 tonnes; 6) Poland: 13357 tonnes; 7) Slovakia: 10877 tonnes; 8) United Kingdom: 4163 tonnes; 9) Honduras: 3400 tonnes; 10) Bulgaria: 2798 tonnes; 11) Hungary: 2745 tonnes; 12) Portugal: 2661 tonnes; 13) Netherlands: 2563 tonnes; 14) Bangladesh: 529 tonnes; 15) Romania: 528 tonnes; 16) Austria: 503 tonnes; 17) Ghana: 316 tonnes; 18) Greece: 296 tonnes; 19) Iran: 250 tonnes; 20) Belgium: 203 tonnes

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Maize (Corn), Green (2020): 1) United States: US$54307,000; 2) Spain: US$50710,000; 3) Morocco: US$14824,000; 4) United Kingdom: US$12003,000; 5) France: US$8836,000; 6) Honduras: US$8404,000; 7) Netherlands: US$4031,000; 8) Poland: US$3788,000; 9) Slovakia: US$3117,000; 10) Bangladesh: US$1739,000; 11) Hungary: US$1692,000; 12) Portugal: US$994,000; 13) Ghana: US$966,000; 14) Austria: US$852,000; 15) Belgium: US$752,000; 16) Bulgaria: US$671,000; 17) Romania: US$664,000; 18) Ethiopia: US$515,000; 19) Germany: US$395,000; 20) Iran: US$248,000

World’s Top Maize (Corn) Importing Countries

World’s Top Importers of Maize (Corn) (2019): 1) Mexico: 16524045 tonnes; 2) Japan: 15986093 tonnes; 3) Vietnam: 11447667 tonnes; 4) South Korea: 11366877 tonnes; 5) Spain: 10012619 tonnes; 6) Egypt: 8078446 tonnes; 7) Iran: 7388742 tonnes; 8) Italy: 6394217 tonnes; 9) Netherlands: 6383336 tonnes; 10) Colombia: 5992611 tonnes; 11) Taiwan: 4806245 tonnes; 12) China: 4791058 tonnes; 13) Germany: 4562511 tonnes; 14) Algeria: 4356206 tonnes; 15) Turkey: 4347475 tonnes; 16) Peru: 4009801 tonnes; 17) Malaysia: 3755359 tonnes; 18) Saudi Arabia: 3260945 tonnes; 19) United Kingdom: 2781577 tonnes; 20) Morocco: 2731200 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Maize (Corn) (2019): 1) Japan: US$3524630,000; 2) Mexico: US$3190075,000; 3) South Korea: US$2352948,000; 4) Vietnam: US$2312953,000; 5) Egypt: US$1929765,000; 6) Spain: US$1928324,000; 7) Iran: US$1592255,000; 8) Netherlands: US$1361583,000; 9) Italy: US$1244456,000; 10) Colombia: US$1190541,000; 11) Germany: US$1111419,000; 12) China: US$1061586,000; 13) Taiwan: US$979563,000; 14) Turkey: US$847519,000; 15) Peru: US$796540,000; 16) Algeria: US$794654,000; 17) Malaysia: US$787326,000; 18) Saudi Arabia: US$715322,000; 19) Venezuela: US$618394,000; 20) United Kingdom: US$595127,000

World’s Top Corn Flour Exporting Countries

roadside maize vendor World’s Top Exporters of Maize (Corn) Flour (2020): 1) South Africa: 549485 tonnes; 2) United States: 244347 tonnes; 3) Mexico: 232666 tonnes; 4) Brazil: 185268 tonnes; 5) Turkey: 135205 tonnes; 6) Pakistan: 89170 tonnes; 7) Italy: 86738 tonnes; 8) France: 80751 tonnes; 9) El Salvador: 74068 tonnes; 10) Spain: 72918 tonnes; 11) India: 64040 tonnes; 12) Poland: 63852 tonnes; 13) Uganda: 63036 tonnes; 14) Zambia: 53567 tonnes; 15) Germany: 50607 tonnes; 16) Canada: 49963 tonnes; 17) Hungary: 48058 tonnes; 18) Dominican Republic: 46181 tonnes; 19) Colombia: 41819 tonnes; 20) Belgium: 41529 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Maize (Corn) Flour (2020): 1) South Africa: US$167224,000; 2) Mexico: US$131517,000; 3) United States: US$123401,000; 4) Brazil: US$67062,000; 5) Italy: US$58755,000; 6) France: US$41226,000; 7) Turkey: US$37849,000; 8) El Salvador: US$35336,000; 9) Colombia: US$34856,000; 10) Spain: US$27568,000; 11) Uganda: US$26166,000; 12) Germany: US$25507,000; 13) Poland: US$22644,000; 14) India: US$21857,000; 15) Dominican Republic: US$19098,000; 16) Zambia: US$16295,000; 17) Canada: US$15831,000; 18) Belgium: US$15608,000; 19) Hungary: US$13802,000; 20) Honduras: US$11208,000

World’s Top Maize (Corn) Oil Producing and Exporting Countries

World’s Top Producers of Maize (Corn) Oil (2019): 1) United States: 1774200 tonnes; 2) China: 514000 tonnes; 3) Brazil: 168177 tonnes; 4) South Africa: 84800 tonnes; 5) Japan: 80731 tonnes; 6) Italy: 71700 tonnes; 7) France: 69500 tonnes; 8) Belgium: 65600 tonnes; 9) Canada: 63100 tonnes; 10) Turkey: 56800 tonnes; 11) South Korea: 51730 tonnes; 12) Argentina: 48300 tonnes; 13) Venezuela: 41373 tonnes; 14) Hungary: 40200 tonnes; 15) Mozambique: 36580 tonnes; 16) Mexico: 33468 tonnes; 17) Spain: 32500 tonnes; 18) United Kingdom: 30900 tonnes; 19) North Korea: 30245 tonnes; 20) Tanzania: 25402 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters of Maize (Corn) Oil (2020): 1) United States: 214321 tonnes; 2) Turkey: 61395 tonnes; 3) Hungary: 32185 tonnes; 4) Brazil: 31938 tonnes; 5) Belgium: 26242 tonnes; 6) Saudi Arabia: 24268 tonnes; 7) Canada: 20630 tonnes; 8) Argentina: 16623 tonnes; 9) South Korea: 15944 tonnes; 10) Italy: 14815 tonnes; 11) Paraguay: 14255 tonnes; 12) France: 13894 tonnes; 13) United Arab Emirates: 12833 tonnes; 14) Egypt: 11322 tonnes; 15) Germany: 10357 tonnes; 16) Ukraine: 9772 tonnes; 17) China: 9467 tonnes; 18) Malaysia: 9256 tonnes; 19) Austria: 9252 tonnes; 20) Spain: 8812 tonnes

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Maize (Corn) Oil (2020): 1) United States: US$198434,000; 2) Turkey: US$75701,000; 3) Saudi Arabia: US$50405,000; 4) Belgium: US$29324,000; 5) Hungary: US$26535,000; 6) Brazil: US$25809,000; 7) United Arab Emirates: US$19379,000; 8) Italy: US$18178,000; 9) Austria: US$17335,000; 10) South Korea: US$16225,000; 11) France: US$15277,000; 12) Canada: US$15069,000; 13) Malaysia: US$15059,000; 14) Argentina: US$13743,000; 15) China: US$12423,000; 16) Egypt: US$11613,000; 17) Spain: US$10540,000; 18) Germany: US$9325,000; 19) Ukraine: US$8848,000; 20) Tunisia: US$8600,000

World’s Top Sweet Corn Exporting Countries

World’s Top Exporters of Frozen Sweet Corn (2020): 1) United States: 73099 tonnes; 2) Hungary: 53477 tonnes; 3) China: 40353 tonnes; 4) France: 34472 tonnes; 5) Spain: 32921 tonnes; 6) Belgium: 21064 tonnes; 7) Thailand: 20956 tonnes; 8) India: 17912 tonnes; 9) Canada: 17609 tonnes; 10) Poland: 15753 tonnes; 11) Vietnam: 11246 tonnes; 12) New Zealand: 10337 tonnes; 13) Serbia: 8877 tonnes; 14) Slovakia: 7364 tonnes; 15) Netherlands: 4770 tonnes; 16) Peru: 4260 tonnes; 17) Malaysia: 3157 tonnes; 18) Turkey: 3106 tonnes; 19) Austria: 2774 tonnes; 20) Belarus: 1883 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Frozen Sweet Corn (2020): 1) United States: US$95331,000; 2) Hungary: US$55224,000; 3) Spain: US$33324,000; 4) France: US$32029,000; 5) China: US$31249,000; 6) Belgium: US$27241,000; 7) Thailand: US$20939,000; 8) Canada: US$17241,000; 9) Poland: US$15694,000; 10) Vietnam: US$13892,000; 11) New Zealand: US$13612,000; 12) India: US$12833,000; 13) Peru: US$8825,000; 14) Serbia: US$7749,000; 15) Netherlands: US$7559,000; 16) Austria: US$3530,000; 17) Slovakia: US$3185,000; 18) Malaysia: US$2988,000; 19) Turkey: US$2924,000; 20) Germany: US$2687,000

corn harvestingWorld’s Top Exporters of Prepared or Preserved Sweet Corn (2020): 1) Thailand: 213455 tonnes; 2) Hungary: 192761 tonnes; 3) France: 130096 tonnes; 4) China: 77955 tonnes; 5) United States: 70470 tonnes; 6) Belgium: 21861 tonnes; 7) Brazil: 18349 tonnes; 8) Russia: 17975 tonnes; 9) Spain: 16292 tonnes; 10) Netherlands: 9559 tonnes; 11) Germany: 9475 tonnes; 12) Vietnam: 7142 tonnes; 13) Italy: 5395 tonnes; 14) Poland: 4661 tonnes; 15) Uzbekistan: 2619 tonnes; 16) Republic of Moldova: 2481 tonnes; 17) Canada: 2323 tonnes; 18) Peru: 1685 tonnes; 19) United Kingdom: 1630 tonnes; 20) New Zealand: 1619 tonnes

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Prepared or Preserved Sweet Corn (2020): 1) Hungary: US$227809,000; 2) Thailand: US$216275,000; 3) France: US$191850,000; 4) China: US$126305,000; 5) United States: US$86011,000; 6) Spain: US$38247,000; 7) Belgium: US$36248,000; 8) Russia: US$19378,000; 9) Netherlands: US$18935,000; 10) Brazil: US$15819,000; 11) Germany: US$14919,000; 12) Italy: US$9079,000; 13) Vietnam: US$7906,000; 14) Poland: US$5085,000; 15) Uzbekistan: US$3939,000; 16) United Kingdom: US$3638,000; 17) New Zealand: US$2750,000; 18) Republic of Moldova: US$2679,000; 19) Canada: US$2663,000; 20) Mexico: US$2020,000

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2024