FIRST FARMERS IN AMERICA

Cacao, the source of chocolate, an early domesticated crop in America

In Mesoamerica, wild teosinte was transformed through human selection into the ancestor of modern maize, more than 6,000 years ago. It gradually spread across North America and was the major crop of Native Americans at the time of European exploration. Other Mesoamerican crops include hundreds of varieties of locally domesticated squash and beans, while cocoa, also domesticated in the region, was a major crop. The turkey, one of the most important meat birds, was probably domesticated in Mexico or the U.S. Southwest. [Source: Wikipedia]

The earliest domesticated New World plants date back to around 8,000 B.C., the first corn to around 5,000 B.C. In the Americas, as the climate became drier and large animals disappeared in the millennia that followed the ice age people began domesticating of squash, amaranth, chili peppers and avocados and later corn and beans. Agriculture appears to predates the evidence of villages by a few thousands years, with the exception of villages built by marine animal hunters in Peru which didn't appear to catch on in the rest of the Americas.

"In Mexico, however, we have the reverse situation," University of Michigan archaeologist Kent Flannery told the Washington Post. "The first villages don't show up around 1500 B.C.," about 4,500 to 6,500 years after the first cultivation. "There's a long gap where people are still living like hunters and gatherers. One of the major reasons, it seems, is that the most important plant is corn. It doesn't naturally form huge stands like wheat and barely."

Early Americans didn't become true farmers until around 2,700 B.C., when they raised beans, corn and squash instead of relying on gathered wild plants. The original corn plants contain small cobs with unappetizing spiky seeds. "Imagine how desperate you must be to eat that," Flannery told the Washington Post.

Pumpkins are believed to have originated in Central America. Seeds from related plants have been dated to 5500 B.C. Wild chilies probably originated in Bolivia and were carried into Central America by birds. They were cultivated as early as 5000 to 3500 B.C. The Cora Indians believed that the first peppers were created from the testes of the first man and dropped onto the plates of startled guests at a dinner party. In the Inca creation myth, chilies were also one of the four brothers that begat mankind.

Websites and Resources of Early Agriculture and Domesticated Animals: Britannica britannica.com/; Wikipedia article History of Agriculture Wikipedia ; History of Food and Agriculture museum.agropolis; Wikipedia article Animal Domestication Wikipedia ; Cattle Domestication geochembio.com; Food Timeline, History of Food foodtimeline.org ; Food and History teacheroz.com/food ;

Good Websites Archaeology News Report archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com ; Anthropology.net anthropology.net : archaeologica.org archaeologica.org ; Archaeology in Europe archeurope.com ; Archaeology magazine archaeology.org ; HeritageDaily heritagedaily.com; Live Science livescience.com/ ; Food Timeline, History of Food foodtimeline.org ; Food and History teacheroz.com/food

Earliest Evidence of Agriculture in the Americas: 10,000 Year-Old Squash

A) Cucurbita pepo peduncle from zone B of Guilá Naquitz dated to 7,340 years ago; B) Cucurbita pepo fruit end fragment from zone B of Guilá Naquitz dated to 6,980 years ago; C) A squash seed from zone C of Guilá Naquitz 13.8 mm in length, dated to 8,910 years ago

People began developing agriculture in the New World about 10,000 years ago, about 5,000 years earlier than previously thought, according to a report in May 1997 in the journal Science by Smithsonian scientists Bruce D. Smith. This assessment is based on the discovery of the remains of seeds, rinds and stems of a baseball-size squash in a cave named Guila Naquitz near Oaxaca, Mexico, indicating that squash not corn was the first New World crop and that agriculture developed in the New World around the same time that it did in the Near East and Asia.

The shape of the squash seeds found in the cave is different from the seeds of wild squash plants which suggests they were cultivated. Scientists believe that early Americans cultivated the gourds for their high protein seeds or to make something like cups or fishing floats. The fleshy material of the squash they raised was hard, not very tasty and hard to digest, which has lead archaeologists to believe that squash was raised for something other than eating the flesh of the gourd as food. The finding also suggests that agriculture developed gradually in a hunter and gatherer culture in Americas over a period if 6,000 years unlike the Near East and Mesopotamia, where it was relatively easy to cultivate large fields of barely and wheat that could support many people and this led to the relatively quick development of agriculture and villages around the same time.

Spencer P.M. Harrington wrote in Archaeology.org: Originally excavated in 1966 by University of Michigan archaeologist Kent Flannery, then at the Smithsonian, the Guilá Naquitz (White Cliff) Cave revealed evidence of human occupation dating back 10,000 years; finds included squash seeds, rind fragments, and peduncles, or stems. Some of the larger seeds were identified as belonging to a domesticated squash species, Cucurbita pepo, which includes modern pumpkins. Based on radiocarbon dates of charcoal found with the seeds, and on the size and thickness of the rinds, Flannery estimated the squash were nearly 10,000 years old. This date drew fire from some archaeologists who believed the seeds came from later occupation layers and did not offer clear signs of domestication. These scholars have held that the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture occurred between 5,000 and 3,500 years ago. [Source: Spencer P.M. Harrington, Archaeology.org, July/August 1997]

Flannery could not, however, date the specimens directly because radiocarbon-dating techniques then available would have required destroying the samples. Smith used accelerator mass spectrometer radiocarbon dating, which can be used on very small samples, to establish the seeds’ age. “Bruce has vindicated us,” says Flannery. “He’s shown that our excavations didn’t have any mixing of occupation layers.”

So far there is no evidence to suggest that New World people were cultivating anything but squash before 5,000 years ago. While Chinese and Near Eastern peoples appear to have shifted to a diversified agricultural economy within 1,000 years of the cultivation of their first crops, in the Americas the transition to an agricultural life-style appears to have taken much longer. Though Smith hesitates to predict when evidence for other early New World crops will emerge, he does admit that it “would seem unusual to have 5,000 years pass before corn and beans become domesticated.”

Crops Domesticated in Southwest Amazonia 10,850 Years Ago?

Mayan image of chocolate drink

Ancient people in Amazonia began cultivating plants and altering forests earlier than previously thought. In 2022, Archaeology magazine reported: New research within the Llanos de Moxos has revealed that people living in Amazonia some 10,850 years ago were also among the earliest in the world to domesticate and cultivate crops. Sediment analysis showed that the region’s inhabitants created thousands of forest islands within the otherwise treeless savannah by dumping food waste, creating fertile patches on which they were able to grow manioc, squash, maize, and other edible plants. [Source: Archaeology magazine, July-August 2020]

Popular Archaeology reported: The remains of domesticated crop plants at an archaeological site in southwest Amazonia supports the idea that this was an important region in the early history of crop cultivation, according to a study published July 25, 2018 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Jennifer Watling from the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at the University of São Paulo, Brazil and colleagues. [Source: Popular Archaeology, July 25, 2018]

Genetic analysis of plant species has long pointed to the lowlands of southwest Amazonia as a key region in the early history of plant domestication in the Americas, but systematic archaeological evidence to support this has been rare. The new evidence comes from recently-exposed layers of the Teotonio archaeological site, which has been described by researchers as a “microcosm of human occupation of the Upper Madeira [River]” because it preserves a nearly continuous record of human cultures going back approximately 9,000 years.

See Separate Article: FIRST HUMANS AND SETTLEMENTS IN THE AMAZON factsanddetails.com

Early Development and the Late Arrival of Villages in the Americas

Maya nobleman offering cocoa pasteThe first known permanent Americans houses (in the Tehuacán Valley in Mexico) date back to around 3,400 B.C. In contrast, villages developed in Turkey and Jordan around 7,500 B.C. By 1500 B.C. villages were widely scattered throughout the Americas. At this time pottery was widely used and villagers possessed small clay idols, which suggested organized religious beliefs. The New World's earliest civilizations developed when early farming communities became established and socially organized.

"The earliest villages in Europe and Asia were built 1,000 to 2,000 years before the development of the farming economy," Columbia anthropologist Marvin Harris wrote in Cannibals and Kings . “Whereas, the domestication of plants in the New World took place thousands of years after people settled in villages."

People in the Americas didn't settle in permanent villages because they found it more advantageous to remain hunters and gatherers. It appears that crops were domesticated at sites near different hunting grounds so that people could move around and not deplete the huntable animals — such as woodland deer, rabbits, turtles, other small animals, and birds — in one place. The roving hunting methods are believed to be linked with the overhunting and extinction of large animals across the Americas.

Hunting is more inefficient in the forests and mountains that cover most of the Americas. In areas where there were large grasslands, namely the Great Plains of the United States — which are somewhat similar to the grasslands in Anatolia and the Middle East where grains were first cultivated — people chose follow herds of buffalo and hunt them and get what they needed from them rather than develop agriculture.

Lack of Wheel and Domesticated Animals in the Americas

The Maya originated a complex system of writing and pioneered the mathematical concept of zero. Yet they never built the wheel and the only animal they domesticated for food was the turkey. In addition to not having the wheel it doesn't seem the Maya used metal either. Most of their tools were made from stone. Good goods were transported overland on the backs of human beings rather by pack animals or carts. When you consider that they built the incredible cities they did without animals and metal their achievements seem all that much more remarkable.

In New World, the wheel was invented by Indians as a children's toy and used in pottery, but was not used more extensively arguably because of a lack of a good beasts of burden. Failure to develop the wheel left the New World technologically behind the Old World.

Anthologists believe that Old World people developed more quickly and became more technologically advanced than people in the New World because they domesticated animals earlier which in turn made it easier for them to get around easier and perform labor that required beasts of burden.

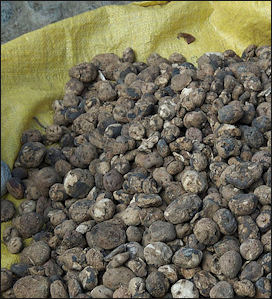

First Potatoes

Andes potatoes Potatoes are one of the worlds’ oldest foods. The have been grown in their place of origin, South America, as long as the first cultivated in the Fertile Crescent. The first wild potatoes were harvested as high as 14,000 feet in Andes perhaps as long as 13,000 years. Of the seven cultivated species of potato six are still grown only in the upper elevations of the Peruvian Andes. The seventh, S. tuberosum, grows in the Andes too, where it is known as “unproved potato” but also grows well at lower elevations and is grown all over the world as dozens of different vanities of potatoes that we know and love.

The wild potato-like plants come in wide variety and range over an area in the Andes that extends from Venezuela to northern Argentina. There is so much diversity among these plants that scientists have long thought that early potatoes were cultivated at different times in different places, perhaps from different species. A study in the mid 2000s by scientist from the University of Wisconsin of 365 specimens of potato as well as primitive species and wild plants seems to indicate that all modern potatoes come from a single species, the wild plant Solanum bukasovi , native to southern Peru.

Evidence of potato domestication has been found at a 12,500-year-old archeological site in Chile. Potatoes are thought to have been first widely cultivated around 7000 year ago. Before 6000 B.C. nomadic Indians are believed to have collected wild potatoes on the central Andean plateau, 12,000 feet high. Over the millennia they developed potato agriculture.

See Separate Article POTATOES: HISTORY, FOOD AND AGRICULTURE factsanddetails.com

First Corn

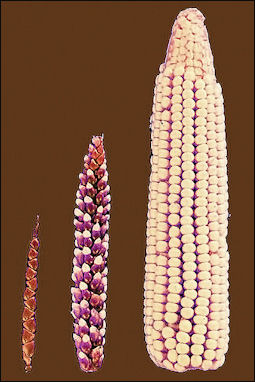

Most scientists believe that corn (maize) originated from teosinte a weedy wild grass still found in remote areas of Mexico that has inch-long "ears" and look more like wheat than corn. Some scientists believe it comes from criollo, a plant native to a remote region of Sierre Norte de Oaxaca in Mexico, or cornlike plant that has since become extinct. Primitive corncobs from these plants found in a Oaxaca cave were dated to 6,300 B.C. In 2001, based of DNA studies, scientists concluded that corn did in fact evolve from teosinte. It is believed that ancient people in southern Mexico and Central America began harvesting grains from wild teosinte about 10,000 years ago. Through selective breeding these plants developed large stalks and seeds and eventually these became the cobs we associate with corn today.

teosinte on the left Jessica Boddy wrote in Science: ““The first glimpses of maize domestication came in the 1960s, when esteemed U.S. archaeologist Richard MacNeish excavated at caves in Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley, a center of early Mesoamerican agriculture. In the dry, dark environment there, he found tiny, well-preserved maize cobs dated to roughly 5300 years ago and harboring only 50 kernels each, compared with the 1000 on modern cobs.” [Source: Jessica Boddy, Science, November 21, 2016]

Most historians believe corn was domesticated in the Tehuacán Valley of Mexico or the the adjacent Balsas River Valley of south-central Mexico An influential 2002 study by Matsuoka et al. demonstrated that, rather than the multiple independent domestications model, all maize arose from a single domestication in southern Mexico about 9,000 years ago. The study also demonstrated that the oldest surviving maize types are those of the Mexican highlands. Later, maize spread from this region over the Americas along two major paths. This is consistent with a model based on the archaeological record suggesting that maize diversified in the highlands of Mexico before spreading to the lowlands. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Archaeologist Dolores Piperno said: “A large corpus of data indicates that it [maize] was dispersed into lower Central America by 7600 BP [5600 BC] and had moved into the inter-Andean valleys of Colombia between 7000 and 6000 BP [5000–4000 BC]. [Source: Dolores Piperno, “The Origins of Plant Cultivation and Domestication in the New World Tropics: Patterns, Process, and New Developments”]

See Separate Article: CORN (MAIZE): HISTORY, AGRICULTURE AND PRODUCERS factsanddetails.com

Origin of Chocolate

Cacao beans come from a rain forest plant that hails from the lower Amazon basin, where Indians know the plants mostly as a source of a pulpy fruit with a lemony taste and has a pearlike texture. Genetic research indicates some these South American plants made their way to what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize where they were cultivated by native people living there. It is not known why people started consuming the beans because they have a very bitter flavor.

Early Americans began consuming early forms of chocolate at least as early as the 12th century B.C. In 2007, residue from fermented cacao pulp was found in a chocolate pot dated to 1150 B.C. that was unearthed in Honduras. The residue appears to have come from an alcoholic drink that archeologists involved with the discovery have theorized may have been used to celebrate new births and weddings. The discovery was made by team led by John Henderson, a professor of anthropology at Cornell. The team found traces of theobromine, a chemical found only in the cacao plant, on elegant pottery, thought to be used in ceremonial occasions, unearthed at the Puerto Escondido site in the Ulua Valley of Honduras.

Henderson reported his finding in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. He has theorized that chocolate was discovered by early Americans trying to brew a kind of beer later called “chicha” by the Spanish. Theobromine was found in 11 of 13 vessels examined, the vessels were designed for pouring and drinking and resemble vessels used later in Mesoamerica for marriage and birth ceremonies. Henderson told the New York Times, “Cacao was the social grease of Mesoamerica.”

Early History of Chocolate

Seated Male with Trophy Heads

and Cup (perhaps for cacao drink)

from Colima The Olmec, who established a civilization in the Gulf Coast of Mexico around 1300 B.C., drank cacao. They called their drink “kakawa”. Semi-wild trees can still be found in the humid lowlands they inhabited.

The Mayas drank concoctions made of sweetened chocolate and water and had a glyph for cacao. They had a god of chocolate and used cacao as a currency. Studies of pots used to make chocolate by the Mayans indicate that liquid chocolate was brewed into a froth to produce foam, which the Mayans considered the most delicious part of the drink. The foam was created by using spouts, through which a chief would blow air as the drink was poured from one vessel to another.

Cacao was believed to have been brought to earth by the great god Quetzalcoatl, who promised mankind an endless supply of the stuff in the afterlife. Only nobleman and trusted soldiers were allowed to drink it. The Toltecs staged rituals for “ xocoatl” (meaning "bitter water" or "chocolate") in which chocolate-colored dogs were sacrificed. Itza human sacrifice victims were sometimes give a cup of chocolate before their execution.

Book:” True History of Chocolate” by Sophie and Michael Coe is said to have the best account of chocolate in New World.

Avocados

In the past avocados have been associated with religion, healing, love, mortality, status and beauty. Ancient Aztecs, Mayans and Incas ate them and believed that they nourished the body externally as well as internally. Mayan folklore tells how the famous Indian, Seriokai, was able to trace his unfaithful wife to the end of the world. The lovers adored avocados and ate them wherever they went. Seriokai followed the young trees, which sprang from the discarded seeds. [Source: Ancientfoods, April 19, 2010]

In Mexico, the avocado has long been considered an aphrodisiac. An old Aztec legend describes how young and beautiful maidens were kept in their rooms for protection during the height of the avocado season.

Nutritionally, avocados are good sources of protein, Vitamins A, C and E, and the B Vitamins thiamin, riboflavin and niacin and the mineral magnesium and other trace minerals. It is also high in potassium. (One cup of avocado cubes has about 900 mg.) Avocados are low in calories, contain no cholesterol and are low in sodium.

Domestication of Turkeys by the Mayas and Aztecs

According to York University: “An international team of researchers from the University of York, the Institute of Anthropology and History in Mexico, Washington State University and Simon Fraser University have been studying the earliest indication of domestic turkeys in ancient Mexico. The team studied the spatial remains of 55 turkeys, dating from between 300 B.C.-A.D. 1500 in various parts of pre-Columbian Meso-America. They discovered that Turkeys weren’t just a prized food source, but was also culturally significant for sacrifices and ritual practices. [Source: Heritage Daily, York University , January 17, 2018]

Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow in the Department of Archaeology at the University of York, Dr Aurélie Manin, said: “Turkey bones are rarely found in domestic refuse in Mesoamerica and most of the turkeys we studied had not been eaten — some were found buried in temples and human graves, perhaps as companions for the afterlife. This fits with what we know about the iconography of the period, where we see turkeys depicted as gods and appearing as symbols in the calendar.

“The archaeological evidence suggests that meat from deer and rabbit was a more popular meal choice for people in pre-Columbian societies; turkeys are likely to have also been kept for their increasingly important symbolic and cultural role., “ Dr Camilla Speller of the University of York said: “Even though humans in this part of the word had been practicing agriculture for around 10,000 years, the turkey was the first animal, other than the dog, people in Mesoamerica started to take under their control. Turkeys would have made a good choice for domestication as there were not many other animals of suitable temperament available and turkeys would have been drawn to human settlements searching for scraps”

Some of the remains the researchers analysed were from a cousin of the common turkey — the brightly plumed Ocellated turkey. In a strange twist the researchers found that the diets of these more ornate birds remained largely composed of wild plants and insects, suggesting that they were left to roam free and never domesticated.

The team also measured the carbon isotope ratios in the turkey bones to reconstruct their diets. They found that the turkeys were gobbling crops cultivated by humans such as corn in increasing amounts, particularly in the centuries leading up to Spanish exploration, implying more intensive farming of the birds. Interestingly, the gradual intensification of turkey farming does not directly correlate to an increase in human population size, a link you would expect to see if turkeys were reared simply as a source of nutrition. By analysing the DNA of the birds, the researches were also able to confirm that modern European turkeys descend from Mexican ancestors.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Nature, Scientific American. Live Science, Discover magazine, Discovery News, Ancient Foods ancientfoods.wordpress.com ; Times of London, Natural History magazine, Archaeology magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, BBC, The Guardian, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “History of Warfare” by John Keegan (Vintage Books); “History of Art” by H.W. Janson (Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.), Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated June 2024