ANIMAL PLAY AND BEHAVIORS

A number of studies seem to indicate that animals feel pain. On study, for instance showed that rats and chickens prefer bad-tasting feed with pain killers over good-tasting feed without pain killers. Other studies and anecdotal evidence seems to indicate that although animals feel pain it doesn’t bother them as much as it bothers humans.

Seattle biologist Bruce Bagemihl estimates 450 animal species exhibit some form of homosexual behavior, which includes same-sex courtship, displays of affection, sexual activity, long-tern pairing and parenting. Animals used to roaming around and covering large distances on foot such as elephants, antelope and bears are often the ones seem the unhappiest and get the most neurotic in zoos while creatures that spend a lot of time sitting around like wild cats and hanging out like monkeys and apes are relatively okay.

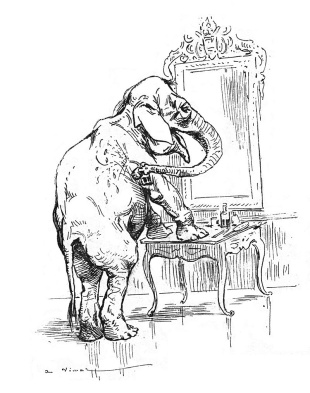

On human-like behaviors displayed by animals, Yudhijit Bhattacharjee wrote in National Geographic: A water buffalo in a zoo enclosure working hard to flip over a turtle that’s flailing on its back, then acknowledging cheers from onlookers with what sure looks like a self-satisfied air. A panda sledding down a snow-covered hill, then trudging up to do it again. A monkey on the edge of a canal peeling a banana and gaping with dismay when it plops into the water. Ravens seem to respond to the emotional states of other ravens. Many primates form strong friendships. In some species, such as elephants and orcas, the elders share knowledge gained from experience with the younger ones. Several others, including rats, are capable of acts of empathy and kindness. [Source: Yudhijit Bhattacharjee, National Geographic, September 15, 2022]

In the wild, dolphins play chase with one another. They’re just one of many species—in addition to dogs and cats, as everyone knows—that engage in play. Baboons have been seen teasing cows by pulling their tails. While studying elephants in Africa, Richard Byrne, who researches the evolution of cognition, often observed young elephants pursue animals that posed no threat, such as wildebeests and egrets. Scientists also have collected evidence of playful behaviors in fish and reptiles, according to Gordon M. Burghardt, an ethologist at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville. He’s observed Vietnamese mossy frog tadpoles repeatedly riding air bubbles released from the bottom of a tank all the way to the top.[Source: Yudhijit Bhattacharjee, National Geographic, September 15, 2022]

Play expends energy and even risks injury, yet it does not always serve an immediate purpose. So why do animals engage in it? Researchers believe play evolved because it helps strengthen bonds between members of social groups. It also helps animals practice skills, such as running and leaping, that improve their chances of survival. That’s the explanation for why play evolved, but what’s the impulse that makes an animal engage in it? A plausible answer—according to Vincent Janik, a biologist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland—is the pursuit of joy. “Why does an animal do something? Well, because it wants to,” he says. In the absence of any other benefit in the moment, it seems likely that play gives animals pleasure, enriching their inner life.

RELATED ARTICLES:

BIODIVERSITY AND THE NUMBER OF SPECIES factsanddetails.com ;

TROPICAL RAINFORESTS: HISTORY, COMPONENTS, STRUCTURE, SOILS, WEATHER factsanddetails.com ;

ANIMALS: TAXONOMY, FEATURES, AND STUDYING THEM factsanddetails.com ;

MAMMALS: HAIR, HIBERNATION AND RUMINANTS factsanddetails.com ;

BIRD BEHAVIOR, SONGS, SOUNDS, FLOCKING AND MIGRATING factsanddetails.com

INSECTS: CHARACTERISTICS, DIVERSITY, USEFULNESS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com ;

LINNAEUS: THE FATHER OF TAXONOMY AND ANIMAL CLASSIFICATIONS factsanddetails.com ;

DARWIN: HIS LIFE, BEAGLE JOURNEY AND EVOLUTION THEORY factsanddetails.com ;

WORLD'S OLDEST LIFE FORMS: STROMATOLITES, ALGAE AND THROMBOLITES ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED ANIMALS: NUMBERS, THREATS, HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Animal Culture

After observing Japanese macaques passing on learned traits, Kinji Imanishi, an ecologist and anthropologist who co-founded the Primate Research Institute in 1967, began viewing things differently than harsh evolutionists. Ben Crair wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “ While Western scientists viewed life as a Darwinian struggle for survival, Imanishi believed harmony undergirded nature, and that culture was one expression of this harmony. He predicted you would find a simple form of culture in any animals that lived in a “perpetual social group” where individuals learned from one another and stayed together over many generations. Anthropologists had never paid attention to animals because most of them assumed “culture” was strictly a human endeavor. Starting in the 1950s, Imanishi’s students at Jigokudani and other sites across Japan discovered that was not the case.

“Nowadays cultures have been recognized not just in monkeys but in various mammals, birds and even fish. Like people, animals rely on social customs and traditions to preserve important behaviors that individuals do not know by instinct and cannot figure out on their own. The spread of these behaviors is determined by the animals’ social relationships — the ones they spend time with and the ones they avoid — and it varies among groups. Researchers have tallied nearly 40 different behaviors in chimpanzees that they deemed to be cultural, from a group in Guinea that cracks nuts to another in Tanzania that dances in the rain. Sperm whale scientists have identified distinct vocal clans with their own dialects of clicks, creating what one scientist called “multicultural areas” in the sea. [Source: Ben Crair, Smithsonian magazine, January-February 2021]

“Culture is so important to some animals that Andrew Whiten, an evolutionary and developmental psychologist at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, has called it a “second inheritance system” alongside genetics. And when animals disappear, so do the cultures they have evolved over generations. Conservation programs can sometimes reintroduce new animals to a habitat, but these newcomers know none of the cultural behaviors of their predecessors. In 2019, the journal Science published two papers arguing that conservation efforts have traditionally overlooked the impact of human activity on behavioral and cultural diversity in animals. The authors of one paper urged the creation of “cultural heritage sites” for chimpanzees, orangutans and whales.

How Animals Feed

No animal can create its own food like a plant does. All animals must get their food from outside their bodies, with the ultimate source being plants. Animals that eat plants directly are called herbivores. Those that eat other animals are called carnivores. Even carnivores are ultimately dependent on plants because the animals they eat either eat plants or animals that eat plants or animals that eat animals that eat plants. Venoms of snakes, spiders and centipedes contain hundreds of toxins. They are often used more as digestion aids than a means to kill prey.

Carnivores are among the most advanced animals. Meat is muscle and is one of the richest, most-energy-packed of all foods. Many carnivores have large brains, in part because catching prey takes more skill and brain power than eating a plant. Carnivores generally have teeth such as canines that are used to stab the victim and perhaps kill it near the front of their mouth and other teeth (“carnassials in mammals) further back in jaws that cut and grind the meat up make it easier to swallow and digest. Unless an ecosystem has been disturbed wherever you find large numbers of herbivores you can find carnivores that feed on them. Most large animals found on the land are mammals.

Carnivorous mammals — or animals — generally fall into two groups: 1) those that feed on large prey; and 2) those that will feed on small bite size prey, often things like insects or earthworms. As a carnivore get bigger in size the more small creatures fail to meet its nutritional needs, with the tipping point being about 20 kilograms, about the size of a coyote, after which point it make more sene to pursue big game.

How Animals Choose Mates

Among many animals, when it comes to mating, the female chooses while the males compete with each other for the female’s attention, each trying to show they will provide the best sperm for her offspring. Males are often the biggest sex because they have fight each other and the most decorated because he has to attract the female’s attention. William Eberhard, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Costa Rica, told National Geographic, “Basically the male wants access to the female’s eggs. And he’ll do whatever it takes to please her. But it’s her game; she sets the rules. And she makes the choice.”

Virginia Morell wrote in National Geographic: From fruit flies to elephants, females pick the male (or males) with which they want to mate. The males, in turn, compete with each other to get a female's attention, each vying to show her that he will be the best sperm donor for her babies. That is why, evolutionary biologists say, males are most often the ornamented sex. It is why the male peacock unfurls his dazzling train, why male guppies are adorned with bright orange and blue spots, why male frogs call and male canaries sing. It is even why the genitalia of many males, particularly insects, are as fancy as an Aborigine's embellished didgeridoo, with accoutrements far beyond what's required to get the job done. [Source: Virginia Morell, National Geographic, July 2003]

These days scientific journals are packed with papers on sexual selection and mate choice. In their search to understand how and what females choose, scientists have uncovered an entirely new world of the startling and steamy: Fruit flies that (for their tiny body size) produce some of the largest sperm in the animal kingdom; male millipedes with special legs that exist solely to rhythmically massage a female's reproductive tract, apparently a stimulation she needs before allowing him to inseminate her; a protein in a male mouse's saliva that tells a female mouse if he's Mr. Right. And they've discovered that the females of numerous invertebrates are equipped with sperm storage organs, special pockets where they hold the male's fluid, perhaps assessing its quality. Scientists speculate that the females may nurture the sperm if they accept the contribution, or destroy them if not.

Darwin’s Theory of Sexual Selection

Virginia Morell wrote in National Geographic: Charles Darwin was the first scientist to devise a theory of sexual selection and to recognize that females frequently select mates. He began to develop the notion while writing On the Origin of Species, in which he argued that the related theory of natural selection is the primary force in the evolution of all organisms. Natural selection goes far in explaining why one individual animal survives to pass on its genes to the next generation, while another dies leaving no descendants. It is why female birds are often drably colored (to hide from predators when incubating their eggs), and why gazelles are built for speed (to outrun their enemies). But natural selection does not explain features that would seem to hinder an animal's survival, such as the male peacock's extravagant plumage or a male elk's heavy and unwieldy antlers. How did such unlikely traits — ones that seem to run counter to every Darwinian rule for staying alive — come about? Even Darwin struggled to find a reason, once writing to a friend, "The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail makes me sick!" [Source: Virginia Morell, National Geographic, July 2003]

Eventually Darwin devised a solution, explaining in his 1871 book, The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex, that males' bright colors, baroque ornaments, and elaborate songs are the result of a process he named sexual selection. According to Darwin, sexual selection shapes species in two ways — by giving rise to competition among males for mates, and via females' decisions to mate with particular males.

Darwin's fellow evolutionists readily accepted the part of the sexual selection theory suggesting that male competition plays a role in evolution. Many males are equipped with horns and antlers or other weapons, while females are not, and it's easy to see that a male elk with a large rack would have an advantage over his rivals. He could use his antlers to defeat his competitors and mate with more females. And that would give him the chance to have more sons that would inherit his genes for big antlers and his abilities both to defeat other males and inseminate many females.

But the part of the theory suggesting that females choose mates — thus shaping male physiology and behavior and influencing a species' evolution — was immediately attacked from all sides. Another proponent of the theory of evolution, Alfred Russel Wallace, particularly despised the notion and actively lobbied against it. He argued that males were brightly colored and given to song because of their "superabundant energy" during the mating season. For Wallace, natural selection covered everything, including male competition. And he found the idea that females choose mates because they prefer a particular color or ornament ludicrous because it suggested a faculty for taste and discrimination that he believed to be beyond most animals. Throughout most of the 20th century Wallace's opinion prevailed, and Darwin's theory of sexual selection, with its offshoot of female choice, was largely ignored.

"Right into the 1970s people were still laughing at the idea of female choice," says Michael Ryan, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Texas in Austin. "One writer even said that all you had to do was look at our own species to see that females had no input whatsoever in mating decisions. Now, of course, we have tons of examples that show that Darwin was right: It's most often the females that choose."

The biggest boost to the theory of female choice came from a highly influential paper written by evolutionist Robert Trivers in 1972. Reproduction is not an equal equation, said Trivers. Males and females invest different amounts of energy and resources into producing offspring. Males produce many relatively cheap sperm, but females make a set number of expensive eggs. So it makes sense that males compete for access to females, and that females are choosy about the male, or males, they let fertilize them.

What do Females Want?

Virginia Morell wrote in National Geographic: The big question then becomes: What do the females want? Some researchers have speculated that a male's ornaments and vocal beguilements carry information about the quality of his genes, or his immune system, or his parenting abilities. Others have suggested that there is little information in these secondary sexual traits; they exist solely to attract the female. If she chooses a mate that other females regard as handsome, she'll produce attractive, sexy sons who are more likely themselves to be chosen as mates, and so pass on her genes. [Source: Virginia Morell, National Geographic, July 2003]

Michael Ryan contends that although the male's trait itself — the color he displays or the sound he makes — may be arbitrary, there's definitely a reason for the female's choice. "It's generally something that the male has hit on that stimulates something in the female's neurons," says Ryan, who has subjected a variety of species to mate-choice experiments devised to get a female to tell all.

Ryan leads the way into a lab where a walnut-size female Tungara frog swollen with eggs is about to take such a test. In the wilds of the Tungara frog's native Panama, Ryan explains, the males gather in small pools to belt out two-part calls: one part a deep chuck sound and the other a higher pitched whine. The females hear potential consorts and swim to the ones they choose. A selected male climbs aboard a female's back, and she carries him off to fertilize the eggs she will eject.

"The whine portion of the call identifies the species," says Ryan, in essence telling the female, "I'm a male Physalaemus pustulosus." And the chuck indicates the male's size. "Bigger males make deeper chucks," he says. "Females prefer the males with the deepest chucks." Deepest chuck, biggest male, most sperm: By choosing him, a female has the best chance that all of her eggs will be fertilized.

But that's not the end of the story. A lone male with no competition may not make the chuck call; he may only make the whine and still get a female. Not until other males show up does he add his deep-throated love tone. The reason is that the love song has a mixed blessing: Female frogs aren't the only ones listening for big males. Bats, opossums, and other predators are too. "It's a good example of the dilemma males can face," Ryan says. "If a male has to compete with other males to get a female, he must make the chuck call. But the call puts him at risk of being eaten, and thereby removed from the gene pool altogether."

Despite the dilemma of the love song, it's clear what a female Tungara frog is looking for: the biggest male, who can fertilize the most eggs. But sometimes scientists are less sure of what a male characteristic might be saying to a female. Ryan and graduate student Molly Cummings have studied a Mexican swordtail fish, Xiphophorus multilineatus, and found that females prefer males with shiny tails. "We haven't figured out what that shine tells the female about the male," says Cummings, "but females seem to like the brightest males."

One thing the shine does do is sidestep the predator problem faced by male Tungara frogs. "This is what you and I see," Cummings explains, setting a photograph of a gray-black fish on a table. "And this is pretty close to what a female X. multilineatus sees," she says, setting a second photograph, taken under UV light, next to the first. The tail shines with silvery discs and streaks. It turns out that swordtails can see in the UV light range, but, like us, their predators cannot. So the male swordtails seem to have evolved a less risky way of saying to their females: "Look at me. I'm the best." In other cases, researchers have a clearer idea of what male coloring tells a female. In a species of guppies named Poeecilia reticulate, successful males generally have richly colored red-orange spots and stripes along their sides, says Greg Grether, an evolutionary biologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. "They can't make that color without eating a particular orange fruit that's desirable but fairly rare in their native streams in Trinidad," he explains. "So the orange may indicate which males are best at finding the fruit or at outcompeting other males to get to it first."

Scientists have even succeeded in deciphering the message a female reads in a male peacock's train. In a study that surely would have cured Darwin of his loathing for peacock feathers, biologist Marion Petrie showed that the best dads were indeed the fanciest ones. Their chicks weighed more at birth than did the others, and those same chicks were better at evading predators. Darwin postulated that female choice not only could change the characteristics of a given species, but also lead to the creation of new species entirely. Studies of such species as the giant-sperm fruit fly, Drosophila mojavensis, may explain how this can happen.

Such simple preferences on the part of females — for a male of a certain color or shape, or from a particular population — are now thought to be the primary cause for the diversity of wildly decorated jumping spiders found in the Sky Island mountains near Tucson, Arizona, and for the even greater variety of cichlid fishes in Africa's Lake Malawi. "There's no question that Darwin was right about the power of female choice," says Markow. "It can shape males and it can make new species."

Cheating and Fraud in the Animal World

In his book, “The Liars of Nature and the Nature of Liars”, Lixing Sun, a professor of animal behavior and biology at Central Washington University, addresses fraud and cheating in the animal — and human — world. Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in The New Yorker: “It can be found, he says, at all levels of “the biological hierarchy, from the most complex organisms to the least sophisticated.” And this is all for the best. Cheating is a driving force in the history of life—“a powerful catalyst for the creation of diversity, complexity, and even beauty.” [Source Elizabeth Kolbert, The New Yorker, March 27, 2023]

Sun devotes the first half of his book to a sort of biological “FBI: Most Wanted.” One of the slyest, or at least most studied, of nature’s scam artists is the Alcon blue, a lovely, silvery butterfly native to Europe and Central Asia. Female Alcon blues lay their eggs on gentians. The caterpillars that emerge feed on the plants until they have completed three molts. Then, as what is known as fourth instars, they drop to the ground and wait for a passing ant.

To identify their kin, ants rely on chemicals called cuticular hydrocarbons. Alcon-blue caterpillars secrete chemicals that are similar enough that ants are tricked into carrying them home. Once inside the nest, the butterfly larvae are nurtured by their formic friends, who feed them as if they were their own. Research by British and Italian scientists shows that the caterpillars employ an additional ruse. They vibrate to produce a sound that ants normally associate with their queen. Alcon-blue butterflies can be such convincing cons that ants will neglect their own larvae to care for them.

Many species employ similar tactics, a practice known as brood parasitism or, depending on the details, kleptoparasitism. In the insect world, these include cuckoo bees, cuckoo bumblebees, and cuckoo wasps. Among birds, several species of cuckoo, several species of cowbird, some finches, and even some ducks slip their eggs into other birds’ nests. Not infrequently, the interlopers go so far as to kill off their adoptive siblings. The chicks of the greater honeyguide, a brood parasite native to Africa, have special barbs at the end of their beaks just so they can murder their nest mates. As parenting strategies go, brood parasitism is ugly. Clearly, it is also effective: it has evolved independently many times, in several different orders. Sun, for his part, refuses to cast aspersions. “Evolution is not a Socratic philosopher,” he writes.

Another grift common in nature is aggressive mimicry, which is pretty much Batesian mimicry in reverse. Instead of masquerading as a dangerous creature, an aggressive mimic poses as one that’s benign. The Australian death adder spends most of its days hidden in leaf litter, often with only the tip of its tail exposed. It wiggles the tip in a movement that looks just like the writhing of a worm. When an unsuspecting lizard takes the bait, the death adder strikes. (As its name suggests, the death adder is one of the world’s most venomous reptiles.)

Sun is given to punchy pronouncements. There are, he claims, two “laws” of cheating in the animal kingdom, by which he appears to mean two basic methods of deception. In one, an animal exploits another animal’s cognitive weaknesses. Batesian mimicry falls into this category: the strategy works because potential predators either can’t see well enough or lack the wherewithal to distinguish a poisonous butterfly from its double. Brood parasites, too, take advantage of their victims’ cognitive limitations. Birds, it turns out, have poor egg-recognition skills—in some cases, almost comically poor. In one of a series of famous experiments, the Dutch animal-behavior expert Niko Tinbergen showed that a greylag goose, when faced with a choice between rescuing its own egg and rescuing a volleyball, would pick the ball. “To exploit the cognitive loopholes of another species, you only need a good enough disguise to fool your target,” Sun observes. “Often a very crude mimic will suffice.”

The other way that animals cheat, in Sun’s schema, is by issuing false information, or, more plainly, by lying. Many animals (and even plants) communicate with one another; this is often a critical survival skill. But the possibility of communication inevitably opens up the possibility of miscommunication. Crows, for example, issue alarm calls to alert other crows to potential danger. Conniving corvids, according to Sun, “cry wolf” to scare their neighbors from food. Formosan squirrels also issue alarm calls: during mating season, sneaky males squeak out alarms to distract competitors.

Animals, Feeling and Pain

Natasha Daly wrote in National Geographic: ““Humans identify suffering in other humans by universal signs: People sob, wince, cry out, put voice to their hurt. Animals have no universal language for pain. Many animals don’t have tear ducts. More creatures still — prey animals, for example — instinctively mask symptoms of pain, lest they appear weak to predators. Recognizing that a nonhuman animal is in pain is difficult, often impossible. [Source: Natasha Daly, National Geographic, June 2019]

“But we know that animals feel pain. All mammals have a similar neuroanatomy. Birds, reptiles, and amphibians all have pain receptors. As recently as a decade ago, scientists had collected more evidence that fish feel pain than they had for neonatal infants. A four-year-old human child with spikes pressing into his flesh would express pain by screaming. A four-year-old elephant just stands there in the rain, her leg jerking in the air.

Evan Bush of NBC News wrote: There is not a standard definition for animal sentience or consciousness, but generally the terms denote an ability to have subjective experiences: to sense and map the outside world, to have capacity for feelings like joy or pain. In some cases, it can mean that animals possess a level of self-awareness. In that sense, the new declaration bucks years of historical science orthodoxy. In the 17th century, the French philosopher René Descartes argued that animals were merely “material automata” — lacking souls or consciousness. Descartes believed that animals “can’t feel or can’t suffer,” said Rajesh Reddy, an assistant professor and director of the animal law program at Lewis & Clark College. “To feel compassion for them, or empathy for them, was somewhat silly or anthropomorphizing.” [Source: Evan Bush, NBC News, April 20, 2024]

In studies, researchers found that zebrafish showed signs of curiosity when new objects were introduced into their tanks and that cuttlefish could remember things they saw or smelled. One experiment created stress for crayfish by electrically shocking them, then gave them anti-anxiety drugs used in humans. The drugs appeared to restore their usual behavior.

Scientists Say Even Insects May Have Feeling

Evan Bush of NBC News wrote: Bees play by rolling wooden balls — apparently for fun. The cleaner wrasse fish appears to recognize its own visage in an underwater mirror. Octopuses seem to react to anesthetic drugs and will avoid settings where they likely experienced past pain. All three of these discoveries serve as indications that the more scientists test animals, the more they find that many species may have inner lives and be sentient (able to perceive or feel things). A surprising range of creatures have shown evidence of conscious thought or experience, including insects, fish and some crustaceans. [Source: Evan Bush, NBC News, April 20, 2024]

That has prompted a group of top researchers on animal cognition to publish a new pronouncement that they hope will transform how scientists and society view — and care — for animals. Nearly 40 researchers signed “The New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness,” which was first presented at a conference at New York University in April 2024.

The declaration says there is “strong scientific support” that birds and mammals have conscious experience, and a “realistic possibility” of consciousness for all vertebrates — including reptiles, amphibians and fish. That possibility extends to many creatures without backbones, it adds, such as insects, decapod crustaceans (including crabs and lobsters) and cephalopod mollusks, like squid, octopus and cuttlefish.

“When there is a realistic possibility of conscious experience in an animal, it is irresponsible to ignore that possibility in decisions affecting that animal,” the declaration says. “We should consider welfare risks and use the evidence to inform our responses to these risks.”

Jonathan Birch, a professor of philosophy at the London School of Economics and a principal investigator on the Foundations of Animal Sentience project, is among the declaration’s signatories. Whereas many scientists in the past assumed that questions about animal consciousness were unanswerable, he said, the declaration shows his field is moving in a new direction. “This has been a very exciting 10 years for the study of animal minds,” Birch said. “People are daring to go there in a way they didn’t before and to entertain the possibility that animals like bees and octopuses and cuttlefish might have some form of conscious experience.”

Studying Animal Consciousness

Yudhijit Bhattacharjee wrote in National Geographic: Frans de Waal, an Emory University ethologist who has spent a lifetime studying primate behavior, Waal was one of the earliest voices advocating for the recognition of animal consciousness. Starting a couple of decades ago, he says, scientists began to concede that certain species were sentient but argued that their experiences were not comparable to ours, and thus not significant. [Source: Yudhijit Bhattacharjee, National Geographic, September 15, 2022]

Now some behaviorists are becoming convinced that “the inner processes of many animals are as complex as those of humans,” de Waal says. “The difference is that we can express them in language; we can talk about our feelings.” This new understanding, if it becomes widely accepted, could spark a complete rethinking of how humans relate to and treat other species. “If you recognize emotions in animals, including the sentience of insects, then they become morally relevant,” de Waal says. “They are not the same as rocks. They are sentient beings.”

The scientific quest to understand the inner lives of animals, however, is still a relatively nascent enterprise. It’s also controversial. In the view of some scientists, knowing the mind of another species is next to impossible. “Attributing subjective feelings to an animal by looking at its behavior is not science—it’s just guessing,” says David J. Anderson, a neurobiologist at the California Institute of Technology who studies emotion-linked behaviors in mice, fruit flies, and jellyfish. Researchers investigating emotions such as grief and empathy in nonhumans must fend off the charge that they could be anthropomorphizing their subjects.

The way to get closer to the truth is to test inferences made from animal behavior, says David Scheel, a marine biologist at Alaska Pacific University who studies octopuses. “If you look anecdotally through the ages, the notion that dogs are tightly bonded to specific individuals is very clear. But they are domesticated. Can a fox do the same thing? Does a wolf have that emotional range? Does an orca feel that level of attachment to the members of its own pod? Can a dolphin become friends with a group of fish or a scuba diver? Our intuitions lead us astray here all the time. You will get people whose intuition is, That’s fake. Whatever it is, that’s not friendship, and other people who think, Well, that’s just silly. You are denying animals their inner lives.”

Animal Drunkenness

Rachel Nuwer wrote in the New York Times: Humans and other species have a gene mutation that lets them digest alcohol. In other species, it’s missing. Humans are not the only animals that get drunk. Birds that gorge on fermented berries and sap are known to fall out of trees and crash into windows. Elk that overdo it with rotting apples get stuck in trees. Moose wasted on overripe crab apples get tangled in swing sets, hammocks and even Christmas lights. Elephants are the animal kingdom’s most well-known boozers. One scientific paper describes elephant trainers rewarding animals with beer and other alcoholic beverages, with one elephant in the 18th century said to have drunk 30 bottles of port a day. In 1974, a herd of 150 elephants in West Bengal, India, became intoxicated after breaking into a brewery, then went on a rampage that destroyed buildings and killed five people [Source:Rachel Nuwer, New York Times, May 20, 2020]

Humans, chimpanzees, bonobos and gorillas have an unusually high tolerance for alcohol because of a shared genetic mutation that allows them to metabolize ethanol 40 times faster than other primates. The mutation occurred around 10 million years ago, coinciding with an ancestral shift from arboreal to terrestrial living and, most likely, a diet richer in fallen, fermenting fruit on the forest floor.

“To test whether other species independently evolved the same adaptation, Dr. Janiak and her colleagues searched the genomes of 85 mammals that eat a variety of foods and located the ethanol-metabolizing gene in 79 species. But they identified the same or similar mutation as humans in just six species — mostly those with a diet high in fruit and nectar, including flying foxes and aye-aye lemurs. But most other mammals did not possess the mutation, and in some species, including elephants, dogs and cows, the ethanol-metabolizing gene had lost all function. “It was far more likely for animals that eat the leafy part of plants or for carnivores to lose the gene,” said Amanda Melin, a molecular ecologist at the University of Calgary and a co-author of the study. “The takeaway is that diet is important in what we see happening in molecular evolution.”

“Some results were unexpected. Tree shrews, for example, drink “copious amounts” of fermented nectar with ethanol content equivalent to weak beer, Dr. Melin said, but they never show signs of inebriation. Yet tree shews do not share the same enzyme-producing mutation as humans. This implies that “there’s multiple, different ways to solve this problem,” she said.

Animal Navigation

Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker: Many animals navigators are “humble and unsung, and learning about them is one of the pleasures of “Supernavigators: Exploring the Wonders of How Animals Find Their Way,” by David Barrie, and “Nature’s Compass: The Mystery of Animal Navigation,” by the science writer Carol Grant Gould and her husband, the evolutionary biologist James L. Gould. [Source: Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, March 29, 2021]

“More generally, the astonishment is that any physiology can contain a navigational system capable of such journeys. A bird that migrates over long distances must maintain its trajectory by day and by night, in every kind of weather, often with no landmarks in sight. If its travels take more than a few days, it must compensate for the fact that virtually everything it could use to stay oriented will change, from the elevation of the sun to the length of the day and the constellations overhead at night. Most bewildering of all, it must know where it is going — even the first time, when it has never been there before — and it must know where that destination lies compared with its current position. Other species making other journeys face additional difficulties: how to navigate entirely underground, or how to navigate beneath the waters of a vast and seemingly undifferentiated ocean.

“Some animals plainly do have such a map, or, as scientists call it, a “map sense” — an awareness, mysterious in origin, of where they are compared with where they’re going. For some of those animals, certain geographic coördinates are simply part of their evolutionary inheritance. Sand hoppers, those tiny, excitable crustaceans that leap out of the way when you stroll along a beach, are born knowing how to find the ocean. When threatened, those from the Atlantic coast of Spain flee west, while those from its Mediterranean coast flee south — even if their mothers were previously translocated and they hatched somewhere else entirely. Likewise, all those birds that embark on their first migrations alone must somehow know instinctively where they are going.

How Animals Navigate

Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker: “How might an animal accomplish such things? The Goulds, in “Nature’s Compass,” outline several common strategies for staying on course. These include taxis (instinctively moving directly toward or directly away from a given cue, such as light, in the case of phototaxis, or sound, in the case of phonotaxis); piloting (heading toward landmarks); compass orientation (maintaining a constant bearing in one direction); vector navigation (stringing together a sequence of compass orientations — say, heading south and then south-southwest and then due west, each for a specified distance); and dead reckoning (calculating a location based on bearing, speed, and how much time has elapsed since leaving a prior location). Each of these strategies requires one or more biological mechanisms, which is where the science of animal navigation gets interesting — because, to have a sense of direction, a given species might also need to have, among other faculties, something like a compass, something like a map, a decent memory, the ability to keep track of time, and an information-rich awareness of its environment. [Source: Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, March 29, 2021]

“The easiest of these mechanisms to understand are those that most closely resemble our own. Most humans, for instance, routinely navigate based on a combination of vision and memory, and we are not alone. One scientist, puzzled to find that his well-trained rats no longer knew their way around a maze after he moved it across his lab, eventually determined that they had been navigating via landmarks on the ceiling. (That was a blow to the notion, much beloved by behaviorists, that such rats were just learning motor sequences: ten steps forward, turn right, three steps forward, there’s the food.) Other animals use senses that we possess but aren’t very adept at deploying. Some rely on smell; those migrating salmon can detect a single drop of water from their natal stream in two hundred and fifty gallons of seawater. Others use sound — not in the simple, toward-or-away mode of phonotaxis but as something like an auditory landmark, useful for maintaining any bearing. Thus, a bird in flight might focus on a chorus of frogs in a pond far below in order to orient itself and correct for drift.

“Many animals, however, navigate using senses alien to us. Pigeons, whales, and giraffes, among others, can detect infrasound — low-frequency sound waves that travel hundreds of miles in air and even farther in water. Eels and sharks can sense electric fields and find their way around underwater via electric signatures. And many animals, from mayflies and mantis shrimp to lizards and bats, can perceive the polarization of light, a helpful navigation cue that, among other things, can be used to determine the position of the sun on overcast days.

“Other navigational tools are simultaneously more prosaic and more astounding. If you trap Cataglyphis ants at a food source, build little stilts for some of them, give others partial amputations, and set them all loose again, they will each head back to their nest — but the longer-legged ones will overshoot it, while the stubby-legged ones will fall short. That’s because they navigate by counting their steps, as if their pin-size brains contained a tiny Fitbit. (On the next journey, they’ll all get it right, because they recalibrate each time.) Similarly, honeybees adjust their airspeed in response to headwinds and tailwinds in order to maintain a constant ground speed of fifteen miles per hour — which means, the Goulds suggest, that by tracking their wing beats the bees can determine how far they have travelled.

Magnetism and Animal Navigation

Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker: “How do they do it? At present, the most compelling theory is that they make use of the earth’s magnetic field. We know about this ability because it is easy to interfere with it: if you release homing pigeons on top of an iron mine, they will be terribly disoriented until they fly clear of it. When scientists went looking for an explanation for this and similar findings, they found small deposits of magnetite, the most magnetic of earth’s naturally occurring minerals, in the beaks of many birds, as well as in dolphins, turtles, bacteria, and other creatures. This was a thrilling discovery, quickly popularized as the notion that some animals have built-in compass needles. [Source: Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, March 29, 2021]

The ability to detect and orient using the magnetic field is fairly common in the animal kingdom overall, according to Bryan Keller of Florida State University. Aylin Woodward wrote in Business Insider: Scientists have observed that type of behavior in bacteria, algae, mud snails, lobsters, eels, stingrays, honey bees, mole rats, newts, birds, fish like tuna and salmon, dolphins, and whales. Sea turtles, too, rely on magnetic cues when they migrate thousands of miles to lay eggs on the same beaches where they hatched. Dogs, meanwhile, can find their way home both using their impressive sense of smell and by orienting themselves using the magnetic field, according to one study. "The magnetic field may provide dogs with a 'universal' reference frame, which is essential for long-distance navigation," that study said. See Sharks, Dogs, Sea Turtles[Source: Aylin Woodward, Business Insider, May 7, 2021]

Schulz writes: “As with many thrilling and popular scientific ideas, however, this one started to look a little strange on closer inquiry. For one thing, it turned out that birds with magnetite in their beaks weren’t navigating based on north-south alignment, as we humans do when using a compass. Instead, they were relying on the inclination of the earth’s magnetic field — the changing angle at which it intersects the planet’s surface as you move from the poles to the equator. But inclination provides no clues about polarity; if you could sense it, you would know where you were relative to the nearest pole, but you wouldn’t know which pole was nearest. Whatever the magnetite in birds is doing, then, it does not seem to function like the needle in a compass. Even more curiously, experiments showed that birds with magnetite grew temporarily disoriented when exposed to red light, even though light has no known effect on the workings of magnets.

“One possible explanation for this strange phenomenon lies in a protein called cryptochrome, which is found in the retina of certain animals. Some scientists theorize that, when a molecule of cryptochrome is struck by a photon of light (as from the sun or stars), an electron within it is jolted out of position, generating what is known as a radical pair: two parts of the same molecule, one containing the electron that moved and the other containing an electron left unpaired by the shift. The subsequent spin state of those two electrons depends on the orientation of the molecule relative to the earth’s magnetic field. For the animal, the theory goes, a series of such reactions somehow translates into a constant awareness of how that field is shifting around it.

“If you did not quite grasp all that, take heart: even researchers who study the relationship between cryptochrome and navigation do not yet know exactly how it works — and some of their colleagues question whether it works at all. We do know, though, that the earth’s magnetic field is almost certainly crucial to the navigational aptitude of countless species — so crucial that evolution may well have produced many different mechanisms for sensing the field’s polarity, intensity, and inclination. Taken together, those mechanisms would constitute the beginnings of a solution to the problem of true navigation. And it would be an elegant one, capable of explaining the phenomenon across a range of creatures and conditions, because the magnetic field is omnipresent on this planet. Given some means of detecting it, you could rely on it by day and by night, in clear weather and in foul, in the air and over land and underground and underwater.

How Humans Mess Up Animal Navigation

The ways humans mess up animal navigation “takes countless forms.” Kathryn Schulz wrote in The New Yorker: “ Illegal logging is destroying the mountain ecosystems of western Mexico, where monarch butterflies overwinter. Glyphosate, one of the world’s most commonly used herbicides, is interfering with the navigational abilities of honeybees. Our cities stay lit all night, confusing and imperilling both those animals that are drawn to light and those that rely on stars to plot their course. And as we appropriate more and more land for those cities and for timber and agriculture, the portion available for other species grows correspondingly smaller. The Yellow Sea, for instance, was once lined with nearly three million acres of wetlands that served as a vital stopover for millions of migrating shorebirds. In the past fifty years, two-thirds of those wetlands have vanished, lost to reclamation — a word that suggests, Weidensaul writes, bitterly but accurately, “humanity taking back something that had been stolen, when in fact the opposite is true.” Species that rely on those wetlands are dwindling at rates of up to twenty-five per cent per year. [Source: Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker, March 29, 2021]

“And then there is climate change, which poses by far the greatest threat to the customary movement of animals around the earth. No species is unaffected by it, but long-distance navigators are particularly at risk, partly because they are reliant on more than one ecosystem and partly because the cues they use to get ready for their journeys — typically, the ratio of daylight and darkness — are increasingly decoupled from the conditions at their destinations. That is bad for the migrant, which even under optimal circumstances arrives desperately depleted from its travels, and terrible for its offspring, which may be born too late to take advantage of peak food availability. In no small measure, this pattern is to blame for the plummeting numbers of countless bird species.

“Problems like these aren’t caused by higher temperatures, per se. The Goulds point out that, throughout the two-hundred-million-year evolutionary history of birds and the six-hundred-million-year evolutionary history of vertebrates, “average global temperatures have ranged from below freezing to above one hundred degrees Fahrenheit.” During that time, the ocean has been both hundreds of feet higher and hundreds of feet lower than it is today. Not every species survived those fluctuations, but most animals can adapt to even drastic environmental change, if it happens gradually. Ornithologists suspect that those bar-headed geese fly over Mt. Everest because they have been doing so since before it existed. When it began rising up from the land, some sixty million years ago, they simply moved upward with it.

“The first problem with our current climate crisis, then, is not its nature but its pace: in evolutionary terms, it is a Mt. Everest that has arisen overnight. In the next sixty years, the range of one songbird, the scarlet tanager, will likely move north almost a thousand miles, into central Canada. All on its own, the bird could make that adjustment fairly swiftly — but there is no such thing in nature as a species all on its own. The tanager thrives in mature hardwood forests, and those cannot simply pick up their roots and walk to cooler climates. Compounding this problem of pace is a problem of space. Over the past few centuries, we have confined wild animals to ever-smaller remnants of wilderness, surrounded by farmland or suburbs or cities. When those remnants cease to provide what the animals need, they will have nowhere left to go.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Mostly National Geographic articles. David Attenborough books, Live Science, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2025