BEDOUINS

Bedouins are Arabs and desert nomads who hail from and continue to live primarily in the Arabian peninsula and the Middle East and North Africa. They the have traditionally lived in the arid steppe regions along the margins of rain-fed cultivation. They often occupy areas that receive less than 5 centimeters of rain a year, sometimes relying on pastures nourished by morning dew rather than rain to provide water for their animals.

Bedouins regard themselves as true Arabs and the “heirs of glory.” They are found mostly in Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman and Egypt. Bedouins are objects of romance and associated with the idea of freedom for many Arabs. But there life is not easy. Wilfred Thesinger described the Bedouin’s life as “hard and merciless...always hungry and usually thirsty.”

Bedouin means "desert people." The term Bedouin is an anglicization of the Arabic word “bedu”. It has traditionally been used to differentiate between nomads who made a living by raising livestock (the Bedouins) and those who worked on farms or lived in towns. There is some debate as to whether non-Arab- speaking nomads who live in the Middle East are Bedouins. These groups generally prefer names like the Fedaan tribe or the Rashaayda Arabs to Bedouins.

Arab culture considers the Bedouin people to be "ideal" Arabs due to the purity of their society and lifestyle. Bedouins speak dialects of Arabic and are related ethnically to city Arabs. Their territory stretches from the vast deserts of North Africa to the rocky sands of the Middle East. Most are Sunni Muslims; some are Shia Muslims.

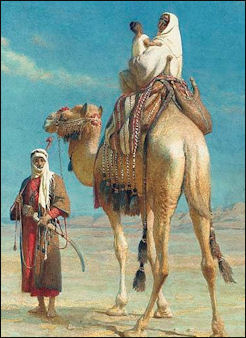

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: “Most Bedouins are animal herders who migrate into the desert during the rainy winter season and move back toward the cultivated land in the dry summer months. Bedouin tribes have traditionally been classified according to the animal species that are the basis of their livelihood. Camel nomads occupy huge territories and are organized into large tribes in the Sahara, Syrian, and Arabian deserts. Sheep and goat nomads have smaller ranges, staying mainly near the cultivated regions of Jordan, Syria, and Iraq. Cattle nomads are found chiefly in South Arabia and in Sudan, where they are called Baqqarah (Baggara). Historically many Bedouin groups also raided trade caravans and villages at the margins of settled areas or extracted payments from settled areas in return for protection. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica]

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: Because Bedouin populations are represented inconsistently—or not at all—in official statistics, the number of nomadic Bedouins living in the Middle East today is difficult to ascertain. But it is generally understood that they constitute only a small fraction of the total population in the countries where they are present. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica]

Total population (21,250,700): Regions with significant populations; 1) Sudan: 10,199,000; 2) Algeria: 230,000-2,257,000; 3) Iraq: 350,000-1,100,000; 4) Jordan: 380,000 (2007); 5) Libya 916,000; 6) Egypt: 902,000 (2007); 7) Syria: 620,000 (2013); 8) Israel: 250,000 (2012); 9) Mauritania: 54,000; 10) Palestine: 30,000; 11) Ethiopia: 2,000 (2004). [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Article BEDOUINS NOMADIC LIFE factsanddetails.com

Book: “Arabian Sands” by Wilfred Thesiger depicts Bedouin culture.

Bedouin Animals and Nomadism

Livestock and herding, principally of goats and dromedary camels comprised the traditional livelihoods of Bedouins. These two animals were used for meat, dairy products and wool. Most of the staple foods that made up the Bedouins' diet were dairy products. Camels, in particular, had numerous cultural and functional uses. Having been regarded as a "gift from God", they were the main food source and method of transportation for many Bedouins. In addition to their extraordinary milking potentials under harsh desert conditions, their meat was occasionally consumed by Bedouins. As a cultural tradition, camel races were organized during celebratory occasions, such as weddings or religious festivals. [Source: Wikipedia]

Some desert people are nomads who move from place to place, tending flocks of goats, sheep and camels. Nomads tend to live in places in which the land is too dry to farm crops and travel to find forage for their animals. Nomads tend to live on the fringes of deserts, where they can find enough fodder for their animals. They pasture their flocks where they can find plants. They eat dates and milk, yoghurt, meat and cheese from animals and trade wool, hides for other goods such as tea and other foods they might want. Some work as smugglers. In lowland areas camel breeding has traditionally been the primary economic activity. In the highland areas, raising sheep and goats is the dominant activity.

Although nomads have traditionally made up smaller numbers than peasants their infleunce on culture has gone far beyond their numbers. It can be argued that Arab culture as well as Turkish culture (the Turks descend from Mongol-like horsemen) is one based in nomadism.

Nomads are far from a homogeneous group. In southeastern Turkey, for example, there are Turkish, Kurdish and Arab nomadic groups. In southwestern Iran, the Khamseh Confederacy includes Persian, Arabic and Turkish tribes. In Morocco, Algeria and Mauritania, Berber and Arab tribes intermix.

There are few nomads anymore. By the end of the 20th century they made up less than 1 percent than of the populations of the nations where they lived. Their numbers have declined steadily in the 20th century. In 1900, nomads made up 35 to 40 percent of the population Iraq. By 1970 they made up only 2.8 percent. In 1900 in Saudi Arabia, nomads made up 40 percent of the population. By 1970 they made up only 11 percent. In 1900 in Libya nomads made up 25 percent of the population. By 1970 they made up only 3.5 percent. Their demise was accelerated by the creation of nation states in the 1950s and the oil wealth.

See Nomadic Life Under Mongols and Horsemen NOMAD LIFE factsanddetails.com ,NOMAD MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com , NOMADS IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com .

Bedouin History

Agricultural and pastoral people have inhabited the southern edge of the arid Syrian steppe since 6000 B.C. By about 850 B.C. a people known as the “A’raab” — ancestors of modern Arabs — had established a network of oasis settlements and pastoralist camps. They were one of many stock-breeding societies that lived in the region during that period and were distinguished from their Assyrian neighbors to the north by their Arabic language and the use of domesticated camels for trade and warfare.

Bedouins were once the primary inhabitants of the Holy Land. Abraham, Isaac and Jacob were probably Bedouins. Many elements of Bedouin culture have not changed much since Biblical times. Bedouins were referred to Qedarites in the Old Testament and Arabaa by the Assyrians (a name still used for Bedouins today). They are referred to as the ‘A’rab in the Quran.

By the first century B.C., Bedouin moved westward into Jordan and the Sinai Peninsula and southwestward along the coast of the Red Sea. In the 7th century Bedouin were among the first converts to Islam. Mohammed was not a Bedouin. He was a townsperson from a family of traders. During the Muslim conquests thousands of Muslims — many of them Bedouins — left the Arabian peninsula and settled in newly conquered land nearby and later spread across of much of the Middle East and North Africa.

Bedouins have traditionally raised livestock for sedentary Arabs. They raised camels, horses, and donkeys as beasts of burden, and sheep and goats for food, clothing and manure. They acquired the camel around 1,100 B.C. Bedouins carried out caravan trade with camels between Arabia and the large city states of Syria. Damascus depended on Bedouins to guide its merchant caravans through the desert.

As traders Bedouins helped moved goods between villages and towns by providing raw materials to the towns and manufactured good to the villages. Their relations with settled people was based on reciprocality and was conducted according to carefully defined rules.

After the Mongol conquests, when irrigations systems in the Middle East were seriously damaged. Sedentary Arabs became more reliant on livestock and forged closer ties with Bedouins, and in some cases joined their tribes.

Bedouins in the Modern World

The number of true nomadic Bedouins is shrinking. Many are now settled. Most Bedouins no longer rely on animals. Centralized authority, borders and the monetary system have undermined their traditional way of life. Roads have decreased their isolation and increased contacts with outsiders. Radios and television have brought new ideas and exposure to the outside world. The oil industry has changed the lives of many Bedouins, who have to deal with oil fields, trucks and other vehicles and machines in areas that were once was only desert. Bedouins still identify themselves as Bedouins if the maintain ties with their nomadic kin and retain the language and other cultural markers that identify them as Bedouins.

Bedouins who have adapted to the modern world retain their tribal loyalties and code of honor. Today, many Bedouins in Oman commute between their desert camps and their jobs in the oil fields in pick-up trucks and SUVs; water is brought to their camps in trucks; and children go to boarding school. While Bedouins continued to move their herds of camels and goats several times a year to new pastures they no longer depend on their animals for survival.

Bedouins in the desert watch television powered by batteries or car batteries. Affluent ones have car phones and satellite television, and goatherds who use ATM machines. One Bedouin in Oman told National Geographic, "Before, life was very difficult. We didn't have enough food. We ate only animals we caught in the desert. We had no water. We drank only camel's or goat's milk. Now we have cars, water, rice — we have everything!"

Bedouins, Nations and Pressures to Abandon Nomadism

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: The growth of modern states in the Middle East and the extension of their authority into previous ungovernable regions greatly impinged upon Bedouins’ traditional ways of life. Following World War I, Bedouin tribes had to submit to the control of the governments of the countries in which their wandering areas lay. This also meant that the Bedouins’ internal feuding and the raiding of outlying villages had to be given up, to be replaced by more peaceful commercial relations. In several instances Bedouins were incorporated into military and police forces, taking advantage of their mobility and habituation to austere environments, while others found employment in construction and the petroleum industry. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica]

In the second half of the 20th century, Bedouins faced new pressures to abandon nomadism. Middle Eastern governments nationalized Bedouin rangelands, imposing new limits on Bedouins’ movements and grazing, and many also implemented settlement programs that compelled Bedouin communities to adopt sedentary or semisedentary lifestyles. Some other Bedouin groups settled voluntarily in response to changing political and economic conditions. Advancing technology also left its mark as many of the remaining nomadic groups exchanged their traditional modes of animal transportation for motor vehicles.

While many Bedouins have abandoned their nomadic and tribal traditions for modern urban lifestyle, they retain traditional Bedouin culture with concepts of belonging to ?aša?ir, traditional music, poetry, dances (like Saas), and many other cultural practices. Urbanised Bedouins also organize cultural festivals, usually held several times a year, in which they gather with other Bedouins to partake in, and learn about, various Bedouin traditions—from poetry recitation and traditional sword dances, to classes teaching traditional tent knitting and playing traditional Bedouin musical instruments. Traditions like camel riding and camping in the deserts are also popular leisure activities for urbanised Bedouins who live within close proximity to deserts or other wilderness areas. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bedouin Language and Religion

Pre-Islamic Arab god Like other Arabs, Bedouins speak different dialects of Arabic such as Bedawi, Hejazi, Najdi and Hassaniyya. A man’s name generally consists of a personal first name, the father’s name and at least the agnatic grandfather’s name. Women keep their father’s family name even after marriage.

Most Bedouins are Sunni Muslims and generally observe Muslim holidays and traditional Muslim customs. Arrangements are usually made with religious specialists in sedentary communities to provide religious services and education for Bedouin communities. Sufism is strong among some Bedouin communities in the southern Sinai and Libya. A few Bedouin groups in Jordan have remained Christian since early Islamic times.

Many Bedouins believe in malevolent spirits called “jinn” and evil ogresses and monsters called “ahl al-ard” (“people of the earth”), who sometimes target people traveling alone in the desert. Following a custom also practiced by Tibetans, Bedouins mark sacred trees and sites with small strips of prayer cloths.

The “envious eye” is taken very seriously by Bedouins. It is believed to target children, who don’t wear amulets for protection.

Bedouins generally follow Muslim practices in regard to funerals and burials. Graves tend to be unmarked. Sometimes an effort is made to bury family members in one place but this often can not be realized within the 24 hour time of Muslim law.

Bedouin Holidays and a Feast for a King

Bedouins in the Lebanon-Syrian area have traditionally gathered in the Bekaa Valley in the spring, arriving with huge flocks of Awassi sheep.

A “mansaf” is a traditional Muslim feast often held to mark the end morning period of a prominent person. A great tent is opened and spread with carpets. Pure white camels are marched within an ocher circle and two dots are marked for a sacrifice. At large feasts 250 sheep might be slaughtered. Meat, rice, spices and bread are placed in a large bowl that is so large it sometimes takes two or more men to carry. Guests sit around on carpets and eat communally out of the bowl. At the end of the meal coffee is served from a shiny, brass coffee pot. The host traditionally does not eat until all of his guests are finished.

Making bread Describing a feast in honor of Jordan's King Hussein, National Geographic reporter Luis Marden wrote: "Opposite the tents and facing them, 200 camelmen, resplendent in bright robes and saddle hangings, awaited the arrival of the king, and far down the track stood two bands of horsemen with rifles to the ready. As the royal car drew abreast, horsemen galloped wildly on each side of the King's car, firing "joy shots" into the air; the camels wheeled behind the horsemen and shouts rose from 4,000 throats."

"Behind the main line of tents, from the women's quarters, sounded the ululation of the “zaghruut”, the peculiar cry with which Arab women greet their leaders or send their men off to war. The chiefs rose t greet His Majesty at the entrance to the big tent, and the instant the King set foot to the ground, men with right armed bared to the elbow plunged curved daggers into jugulars of the white camels."

"Rival bands of horsemen staged mock fights, charging across the sand and firing volleys of shots with their carbines and pistols. Finally the mansaf was served on great dishes, each bearing a roasted whole sheep nestled in a mound of rice and pine nuts, all drenched in rich white sauce made of yoghurt and butter.

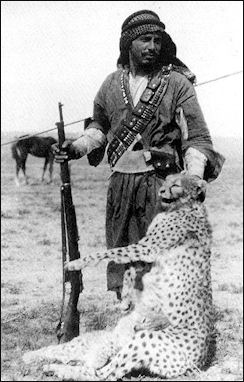

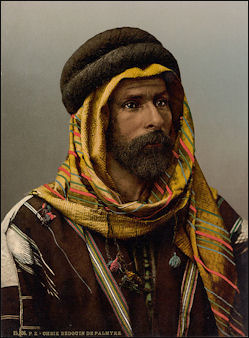

Bedouin Appearance, Customs and Character

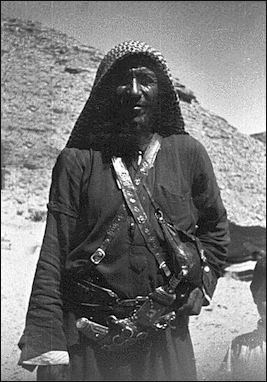

Bedouin Chief of Palmyra Bedouins tend to be small and thin. One reason for this is that food is scarce in the desert. Being thin helps get rid of body heat. Layers of fat keep heat in the body and are more useful in cold weather.

Describing a Bedouin, Don Belt, wrote in National Geographic, he was "short, slim, dark — and had face as fierce as a shrike, with a pointed beak and sharp little beard thrust forward like a dagger." The stereotypical Bedouin male has a masculine, hawk noses, olive skin, and eyes wrinkled by years of squinting in the sun. Some men use a cosmetic made from black antimony to protect their eyes from the sun's glare.

Bedouin have a love of freedom and not being tied down. Explaining the appeal of the nomadic life, one Bedouin nomad told National Geographic: “You are free. You have a relationship only with your animals. The only relationship more important is with Allah.” Calmness and patience are valued traits in the desert. Bedouin submission to fate has been a cornerstone of the Muslim faith. The Bedouin term "green hearted" describes the act of being lighthearted and unconcerned about mundane matters and preferring adventure and danger.

Bedouins have complex customs of revenge, loyalty and hospitality. They are famous for their hospitality. There are stories of Bedouins slaughtering their best camel for a guest only to find out that guest was willing to buy the camel at any price. National Geographic photographer Reza said, “I have been shooting pictures for 35 years and have traveled in 107 different countries, but nowhere have I enjoyed greater warmth that I experience among the Bedouin. Exhausted after a long day driving...you’d approach a tent, and suddenly someone would appear with a coffee and a beautiful carpet to sit on — yet they’d never ask you who you were or where you’re from. I sometimes wonder if the rest of us have forgotten such values.”

Bedouins are expected boil their last rice and kill their last sheep for feed a stranger. Whenever an animal is slaughtered for a guest it is ritually sacrificed in accordance with Islamic law. It is customary in some Bedouin tribes for a host to smear blood from a slaughtered animal onto of the mounth of his guest in a show of hospitality.

Hospitality is regarded as an honor and a scared duty. Visitors who happen by are usually invited to sit and share a cup of thick, gritty coffee. Guest are ritually absorbed into the household by the host. If a conflict occurs the host is expected to defend the guest as if he were a member of his family. One Bedouin told National Geographic, "Even if my enemy appears at this tent, I am bound to feast him and protect him with my life."

Bedouin sometimes touch noses as a greeting. Bedouin men sometimes express their friendship to another man by embracing him and giving him a big wet kiss on the lips.☼

See Bedouin Society

Bedouin Marriage, Weddings and Dating

Traditionally, marriages have been between the closest relatives permitted by Muslim law. Cousin marriages are common, ideally between a man and his father’s brother’s daughter. Traditionally, a father’s brother’s son has first dibs on his female cousin, who has the right of refusal but needs permission of that son to marry anyone else. Although marriages to first cousins are desired, most marriages are between second and third cousins.

Marriages outside the extended family have traditionally been rare, unless a tribal alliances was established; and women were expected to be virgins when they were married. In a marriage it is important for the families to be of the same status. Having lots of children is considered a duty because the more members a tribe has the stronger it is. Polygamy is allowed but only rarely practiced. Generally, only older, wealth men with enough money to support multiple household can afford it.

Traditionally, women family members have acted as matchmakers; old brothers worked out the brideprice paid by the groom’s family and the details of the marriage contract; the bride and groom had to offer their consent; and escape routes had be worked out to save face if one of either the bride or groom backs out. If the marriage is between cousins the brideprice has traditionally been relatively small.

At weddings, Bedouins prepare a feast of goat meat and rice and other foods. The featured dish is often a cooked camel, stuffed with a whole roasted sheep, which in turn is stuffed with a chicken stuffed with fish filled with eggs.

In a traditional Bedouin wedding a camel is sacrificed and a marital tent is set up to signify that a couple can live with each other. At sunset the bride is escorted by female relatives of the groom. After the groom arrives the relatives depart. No presents are exchanged. The following morning the couple is congratulated. The bride then joins the groom’s family in their tents while the grooms does various chores to earn enough money to pay for the bride price.

Among some tribes boys and girls are encouraged o explore their romantic feeling for one another at an early age, even 12. When other family members are working they can be alone in a tent. When it is cold the can hang out by a campfire. If a couple decides they want to marry the young man tells a friend and the friend asked the girl’s father for permission to marry. If approval is given, a tribal elder negotiated the bride price.

Divorce is fairly common and can be initiated by the man or women according to Muslim traditions. When it occurs the woman generally returns to live with her parents

Bedouin Families and Children

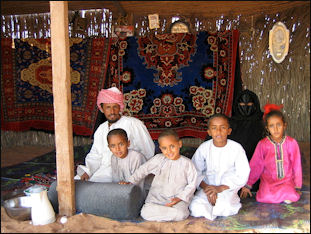

Bedouin family, Wahiba_Sands The three-generation extended household is regarded as the ideal domestic unit and generally consists of nine to eleven members. Although members may sleep in different tents they generally share their meals together. Husband and wife teams tend to remain in larger groups until they have enough offspring to form a group of their own. Some households are created by the unions of brothers or patrilineal cousins.

Bedouins are not respected unless the get married and have children. There are distinct terms for relatives on the mother’s side and relatives on the father’s side. The smallest household unit is generally named after the senior male resident. An extended family household ceases to exist when the elderly husband or wife dies. When a mother is divorced, widowed or remarried her older sons form their own households. Inheritance is divided in accordance with Muslim law. The division of livestock is sometimes complicated by the fact that women are not allowed to own larger animals.

Some Bedouins families are quite large. "We have many children," a Bedouin told journalist Harvey Ardent, "I myself have 17 by my two wives. What else can you do in the desert?"☼

Children and infants are raised by the extended family. Siblings, grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins often are as much engaged in rearing children as the parents. Elaborate ceremonies are held for the naming of newborn children. Children are purified and ritually initiated into the family through rites of seclusion and purification performed by the mother between seven and 40 days after the birth. At age 6 or 7 children are held responsible for taking care of simple household duties and soon after that they are regarded as full working members of the group. Adolescence generally does not get much attention. From late childhood onward Bedouins are treated as working members of the group.

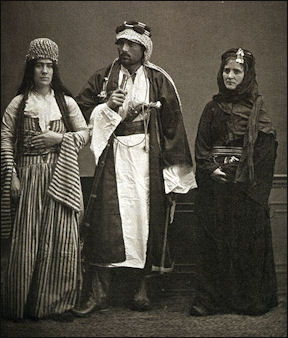

Bedouin Men and Women

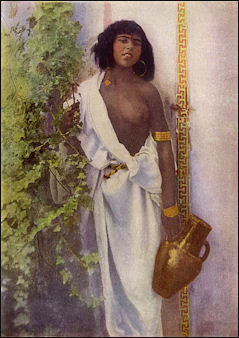

.jpg)

Bedouin woman

early 20th century Men in Bedouin societies are admired if they have a gentle way with camels and an eye for pretty women. Bedouin men have traditionally been taught to secretive about their plans and movements especially where their wives are concerned,

Traditional division of labor has been largely defined by which animals are raised, with men typically caring for the large animals, particularly camels, and women being responsible for the smaller animals such as goats and sheep. Women are often prohibited from having close contact with camels and other large animals. They and older girls spend much of their time herding, feeding and milking When only sheep and goats are kept, men tend to do the herding and women do the feeding and milking.

Bedouin women manage the household and tent and general handle market chores and the buying and selling of goats while only men are allowed to buy and sell camels. Women often spend their days doing chores while the mean relax and drink coffee. Bedouin girls take care of the animals while their brothers go to school.

A woman’s value used to be equated with her worth in camels. A beautiful fair-skinned wife was said to be worth around 50 camels. Girls are sometimes circumcised. Many Bedouin are veiled but in many respects they enjoy more freedoms than urban Arab women.

Bedouin women have traditionally ground wheat into flour on a circular stone called a quern. They have traditionally worked wool into yarn on hand spindles with big pill of coarse wool by their side. Among the items they make are hand-knit camel-udder covers to prevent baby camels from nursing whenever they feel like it.

Bedouin Society

Bedouin in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia As is true with all Arabs, Bedouins live in patrilineal societies. Most are members of large patrilineal descent groups, which are linked by agnation to larger lineage groups, tribes and even confederations of tribes. “Bedouins frequently name more than five generations of patrilineal ancestors and conceptualize relations among descent groups in terms of a segmentary genealogical model, with each group nested in a larger patrilineal group. Within this structure is a framework for forging marriage alliances, and settling disputes and administering justice.

According to Encyclopædia Britannica: Bedouin society is tribal and patriarchal, typically composed of extended families that are patrilineal, endogamous, and polygynous. The head of the family, as well as of each successively larger social unit making up the tribal structure, is called sheikh; the sheikh is assisted by an informal tribal council of male elders. [Source: Encyclopædia Britannica]

In addition to the “noble” tribes who trace their ancestry to either Qaysi (northern Arabian) or Yamani (southern Arabian) origin, traditional Bedouin society comprises scattered “ancestor-less” groups who shelter under the protection of the large noble tribes and make a living by serving them as blacksmiths, tinkers, artisans, entertainers, and other workers.

Social control is exercised through honor and shame which not only defines an individual but also defines his family and even clan. Honor is inherited and has to asserted from time to time to remain relevant. The honor of a man is defined by his individual behavior and those of his male kin. Female honor is something that male relatives are responsible for upholding. It is often defined in terms of chastity and is regarded as something that can not be regained after it has been lost. It is considered a serious, shameful matter if female honor is taken or somehow compromised. Serious breaches of honor can result in execution of expulsion from the tribe.

A widely quoted Bedouin saying is "I am against my brother, my brother and I are against my cousin, my cousin and I are against the stranger" sometimes quoted as "I and my brother are against my cousin, I and my cousin are against the stranger." This saying signifies a hierarchy of loyalties based on proximity of kinship that runs from the nuclear family through the lineage, the tribe, and, in principle at least, to an entire genetic or linguistic group (which is perceived to have a kinship basis). Disputes are settled, interests are pursued, and justice and order are maintained by means of this frame, according to an ethic of self-help and collective responsibility (Andersen 14). The individual family unit (known as a tent or gio[clarification needed] bayt) typically consisted of three or four adults (a married couple plus siblings or parents) and any number of children. [Source: Wikipedia]

When resources were plentiful, several tents would travel together as a goum. These groups were sometimes linked by patriarchal lineage, but were just as likely linked by marriage (new wives were especially likely to have close male relatives join them), acquaintance, or no clearly defined relation but a simple shared membership in the tribe.

Bedouin traditionally had strong honor codes, and traditional systems of justice dispensation in Bedouin society typically revolved around such codes. The bisha'a, or ordeal by fire, is a well-known Bedouin practice of lie detection. See also: Honor codes of the Bedouin, Bedouin systems of justice.

Bedouin Tribes and Sheiks

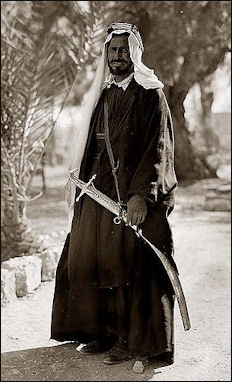

Bedouin Sheikh Most Bedouins belong to small tribes that traditionally lived together in tent camps in the desert. The Al Sawaada tribe, a typical tribe, had 400 members. The largest tribes have 3,000 tents and 75,000 camels. Large tribes are hardly ever together. There simply is not food in a given place in the desert to support them all. Groups that move through the desert usually have 20 to 70 members. ☼

Each Bedouin tribe member wears slightly clothes to indicate locality, social position and marital status, with these things usually being indicated by embroidery on their cloak, headdresses, jewelry and hairstyle worn on special occasions.

Different tribes have different reputations. The Beni Skar Bedouins have a reputation for being particularly fierce. The Duru, the Harasi, the Yal Wahiba are tough Bedouin tribes that live in southern Oman. Residing near their gravel flats of the Empty Quarter, they survive by finding meager feed for their camels and wander from one bitter water hole t another.

Entire tribes are held responsible for a murder or another crime committed by one member of the tribe. In the case of a murder a tribe must wander endlessly to keep one step ahead of the their pursuer until blood money can be raised.

A sheik is the head of a tribe. He is often the wealthiest member of the tribe and may posses more than a thousand camels. Among the important criteria in choosing a leader are age, religious piety, personal qualities, generosity and hospitality.

Sheik generally wield their authority through a chain of command through subtribes, fakhadhs, and buyuut. They have traditionally been in charge of distributing grazing rights and settling disputes. A sheik often has no muscle to back him up and wields power through moral authority and judging the desires of tribe members.

Bedouin Tribal Organization

Bedouins are fiercely loyal to clan and tribe and their society is organized around a series of real and fictional kin groups. The smallest household units are called “bayt” (plural buyuut). They in turn are organized into groups called “fakhadhs”, which in turn are united into tribes. Large tribes are sometimes divided into subtribes. The leaders of buyuut and fakhadhs are often organized into a Council of Elders, often directed by tribal leader or sheik.

Bedouins have traditionally been organized into “nations,” or tribal groups of families united by common ancestor and shared territorial claims. These nations are led by leaders selected according to a universal selection process and operating in an environment that was constantly changing ecologically and politically. Only in the 20th century has their system been undermined by more powerful authoritarianism namely national governments.

The largest scale of tribal interactions is the tribe as a whole, led by a Sheikh (Arabic: ? šay?, literally, "old man"). The tribe often claims descent from one common ancestor—as mentioned above. The tribal level is the level that mediated between the Bedouin and the outside governments and organizations. Distinct structure of the Bedouin society leads to long lasting rivalries between different clans.

The next scale of interaction within groups was the ibn ?amm (cousin, or literally "son of an uncle") or descent group, commonly of three to five generations. These were often linked to goums, but where a goum would generally consist of people all with the same herd type, descent groups were frequently split up over several economic activities, thus allowing a degree of 'risk management'; should one group of members of a descent group suffer economically, the other members of the descent group would be able to support them. Whilst the phrase "descent group" suggests purely a lineage-based arrangement, in reality these groups were fluid and adapted their genealogies to take in new members. [Source: Wikipedia]

Major Bedouin Tribes

Major Bedouin Tribes in Arabia: 1) Harb, large tribe residing on the Arabian peninsula. They live primarily in Saudi Arabia, with their reach extending to Kuwait, Iraq, Egypt and UAE. 2) Anizzah, some tribes of this confederation are Bedouin, they live in Northern Saudi Arabia, Western Iraq, the Persian Gulf states, and the Syrian steppe. 3) al-Duwasir, south of Riyadh. 4) Ghamid, large tribe from Al-Bahah Province, Saudi Arabia, mostly settled, but with a small Bedouin section known as Badiyat Ghamid. 5) Shahran (al-Ariydhah), a very large tribe residing in the area between Bisha, Khamis Mushait and Abha. Al-Arydhah 'wide' is a famous name for Shahran because it has a very large area, in Saudi Arabia. 6) Shammar, a very large and influential tribe in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Jordan. Descended from the ancient tribe of Tayy from Najd. 7) al-Jaloudi (al-Jaludi) of al-Harb ("Goliath's Tribe" of "War Tribe"), one of the largest tribes in the Arabian Peninsula, mostly settled in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Syria and Iraq. The tribe has deep roots in the Umayyad and Abbassid dynasties. 8) Subay', central Nejd. 9) Banu Yam centered in Najran Province, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bedouin Tribes in North Africa: 1) Banu Hilal, some tribes of this confederation are Bedouin, they live in western Morocco, central Algeria, southern Tunisia and Eastern Desert and others steppe of the region. 2) Banu Sulaym, Big tribes, the Sulaym in the east (Libya and southern Tunisia), present in Libya, Tunisia, Algeria and Syria.

Major Bedouin Tribes in the Middle East: 1) al-Hadid, large Bedouin tribe found in Iraq, Syria and Jordan. Now mostly are settled in cities such as Haditha in Iraq, Homs & Hama in Syria, and Amman in Jordan. 2) al-Howeitat, one of the largest tribes in Jordan (al-Hesa). 3) Bani Khalid one of the Bedouin tripes in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Jordan, Egypt and Syria. 4) al-Khassawneh, one of the largest tribes in Northern Irbid Jordan and well known for the long history dominating the North. 5) Dulaim, a very large and powerful tribe in Al Anbar, Western Iraq. 6) al-Majali South Jordan Majalis have long dominated Karak Bedouin society, Strongest tribe in Karak, one of the largest political power in Jordan. 7) Beni Hamida, east of Dead Sea, Jordan. 7) Bani Tameem in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Qatar, Jordan, and Palestinian Territories. 8) Beni Sakhr in Egypt Iraq, Syria and Jordan.

Major Bedouin Tribes in Israel and Egypt: 1) Muzziena tribe in Dahab and South Sinai (Egypt). 2) Tarabin—one of the largest tribes in Egypt (Sinai) and Israel (Negev). 3) Tuba-Zangariyye, Israel near the Jordan river cliff in the Eastern Galilee. 4) 'Azazme, Negev desert and Egypt. 5) al-Mawasi, a group living on the central Gaza Strip coast.

Bedouin Conflicts, Raids and Revenge Killings

Bedouins have traditionally gone out on “ghazwas” ("raids") to settle scores and rustle livestock. An early Arabic poem goes: "With the sword I will wash my shame away,/ Let God's doom bring on me what it may!" In the old days, tribal conflicts often revolved around the rights to water and pastures. Brutal battles and the loss of many lives was often the result of such conflicts. Modern laws and law enforcement officers have largely been able exert control over Bedouins and pacify them.

Bedouin raid in a TV drama

Bedouins have nasty blood feuds that sometimes end in murder. Describing a revenge killing in southern Arabia in 1946, Wilfred Thesiger wrote: "Bin Mautlauq spoke of the raid in which young Sahail was killed. He and fourteen companions had surprised a small herd of Saar camels. The herdsmen had fired two shots at them before escaping, on the fastest of his camels, and one of these shots hit Sihail in the chest. Bakhit held his dying son in his arms as they rode across the plain with the seven captured camels. It was late in the morning when Sahail was wounded, and he lived till nearly sunset, begging for water which they had no t got." " [Source: “Eyewitness to History”, edited by John Carey, Avon, 1987]

"They rode all night to a small Saar encampment under a tree in a shallow valley. A woman was churning butter in a skin, and a boy and girl were milking the goats. Some small children sat under a tree. The boy saw them first and tried to escape but they corned him against a low cliff. He was about fourteen years old, a little younger than Sahail, and unarmed. When they surrounded him he put his thumbs in his mouth as a sign of surrender, and asked for mercy. No one answered him."

Bakhit slipped own off his camel, drew his dagger, and drove it into the boy's ribs. The boy collapsed at his feet, moaning, 'Oh, my father! Oh, my father!' and Bakhit stood over him till he died. He then climbed back into his saddle, his grief a little soothed by the murder...The small, long-haired figure, in white loincloth, crumpled on the ground, the spreading pool of blood, the avid clustering flies, the frantic wailing of the dark-clad women, the terrified children, the shrill incessant screaming of a small baby."

Bedouin Food

Typical Bedouin food includes bread, rice dates, seasoned rice, yoghurt and milk and meat from their animals. Bedouins like to eat goat-and-rice dishes cooked over an open fire. A typical Bedouin breakfast consists of yoghurt, bread and coffee. Nomads have traditionally sold their animals and used the money to buy bags of wheat, rice, barely, salt, coffee and tea, which are carried by their animals.

Bedouin bread is made by women who flatten balls of dough into flat sheets and places them in a rounded stove for baking. Bread can also be baked in the sand or cooked over a campfire in a metal dome.

Dates are the staple of the Bedouin diet. They are harvested from palm trees and dried out in the sun and stored for the wintertime when they supply food for a family and sometimes for camels, goats and sheep. Bedouin can go for months, subsisting on nothing but dates, animal milk and water. Sometimes when swarms of locusts arrive they are collected, roasted and eaten. Some are dried and crushed into powder and stored. Animals are usually only slaughtered for feasts and celebrations.☼

Bedouins have traditionally eaten rice and meat with their fingers while sitting on the ground or floor. When meat is eaten often a large chunk is passed around and everyone cuts of a piece with their dagger. Cooking has traditionally been done outside on camel dung campfires by women. The fire is made in a pit with three stones used as a support for the cooking pot.

Describing a Bedouin feast, Thomas Ambercrombie wrote in National Geographic, "Hardly a word was spoken...We ate busily, thrusting our right hands into the pilaf, squeezing the rice into bite size lumps and popping then into our mouths. The choicer tidbits — lungs, kidneys, an brain — the sheik tore out and laid before his guests. A young boy brought a dish of dates and bowls of fresh camel milk.” Bedouins often signal that a feast is over by licking their fingers and then leave to wash and return for fruit or desert.

Bedouin Drink and Hashish

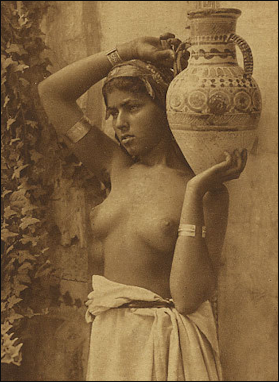

Western idea of a Bedouin beauty Bedouins like to drink thick, gritty coffee traditionally made from green beans crushed in a brass mortar and spiced with cardamom, and sometimes ginger root. Out in the desert the coffee is brewed with water boiled over a brush wood fire and poured from a long-beaked brass pot into porcelain thimble-size cups or small cups that look like egg cups.

Coffee breaks are relished. They are the primary social activities. They are usually exclusively male affairs and sometimes last all day. If a stranger is spotted on the horizon a pot of coffee is brewed to offer with dates as hospitality when they arrive. A guest customarily accepts three servings. Bedouins signal they have had enough to drink by twisting the cup back and forth with their wrist. Coffee has traditionally been one of the most popular backsheesh gifts.

Bedouin “kahwa” is a strong aromatic coffee made with cardamon powder, saffron and rosewater. The coffee beans are roasted over a camel dung fire then ground. After a pinch of cardamon is added the coffee is brewed in a long neck brass pot. Some Bedouin slike Arabic coffee spiced with ginger and filtered with a layer of dried grass.

Bedouin also drink tea. Describing a Bedouin tea ceremony Abercrombie wrote: "Ahmad cracked a tall cone of hard sugar and popped a fist-size chunk into the hot tea along with handfuls of mint leaves, He poured himself a sip, sampling it with all the concern of a french wine taster. Another chink of sugar and it was perfect. He filled our glasses with the brew thick and sweet as syrup. “Bismillah," the sheik intoned before we drank. "In Allah's name."

Bedouins often consume frothy camel milk communally from an aluminum basin. Explaining the attraction of the warm and sweet camel milk straight from the animal, one Omani Bedouin told National Geographic, "This is fresh as it gets. Makes everything digest. We drink it all the time.”

Some Bedouins smoke hashish. Mickey Hart, the drummer in the Grateful Dead, who spent some time with Bedouins in the Sinai, said he had to smoke the “heroic” amounts of hashish to get in good enough graces with his host to record some of their music.

Bedouin Beauty and Hygiene

Men, women, children and infants in Bedouin tribes decorate their eyes with kohl as the ancient Egyptians did. Some Bedouin women have geometric facial tattoos and henna-stained patterns on their calloused hands. Young Bedouin girls begin tying coins in their hair before their front teeth have grown in.

With water in short supply, Bedouins don't take many baths. Before prayers they often wash with sand rather than scarce water. Bedouins wash their hair with powdered leaves of the sidr tree, a thorny fruit tree also know as Christ’s thorn because it believed to have been used to make Christ’s crown of thorns. The leaves are dried and pounded and mixed with water to make a lather.

Bedouin Clothes

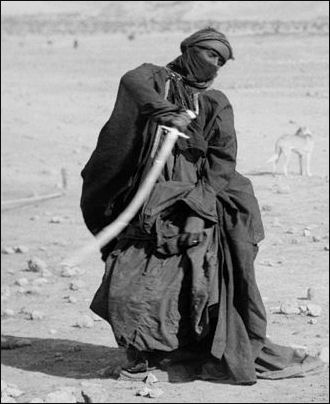

Bedouin sword dance Sun and sand protection is the primary objective with Bedouin clothes. Bedouin garments can be wrap around the wearer to keep the sand and sun out. Loose clothing tends to shield the skin from sun and provide enough open space that heat absorbed by the cloth is not directly transferred to the skin.

Each Bedouin tribe member wears slightly clothes to indicate locality, social position and marital status, with these things usually being indicated by embroidery on their cloak, headdresses, jewelry and hairstyle worn on special occasions. Each tribe has is own designs that are worn on their clothes, Tents and camels bags also carry these designs so that caravans can be identified from a distance.

A typical Bedouin man wear a white cotton foot-length, long-sleeve shirt, an “aba” (a long khaki ankle-length sleeveless robe), and red tasseled sash. Sometimes they wear a dagger in their belt. At night the aba is used a blanket. In many places Bedouin men wear a “thobe” (a long white gown). Sometimes they wear a long sleeve coat called a “gumbaz” or kibber” over the thobe.

Bedouin men tend to wear camel hide sandals, ankle boots or Western-style shoes. Some go barefoot in the hot sand. To make standing in the hot sand bearable sometimes they stand on one and then alternate back and forth with the other foot. If they step on a thorn they use another thorn to dig it out.

On their head Bedouin men wear a Yasser-Arafat-style “keffiyeh” , which can be draped under the chin, lifted across the face for protection against sandstorms, or crossed under the chin and fixed on top of the head for warmth. The cloth headdress held in place by a thick wool cord of made of black goat hair. When it is cold he may wear a round wool cap under the a “keffiyeh” .

Women wear dark clothes and a kerchief held in place with a band of folded cloth. Red is usually worn by married women while blue is worn by unmarried women. Loose cloaks, or “thobe” , are worn for special events. These often feature embroidery around the neckline, sleeves and hems. Veils are often connected to a turban and are decorated with silver coins. Everyday clothes are much plainer. Bedouin women usually wear sandals.

Some Bedouin women wear a “niqab , a mask-like veil that reveals only the eyes and neck and has a narrow ridge that runs down the middle of the face. The veil goes across the face. The small connecting piece near the bridge of the nose is useful for Bedouin women, when riding camels or doing other activities as it prevents their garb from falling down or off. For a woman wearing such a garment only immediate relatives are allowed to see her face. Bedouin women in Saudi Arabia wear a black tent-like cloak over their clothes and a mask that covers the entire faces except for small eyes slits. In the desert most Bedouin women don’t wear veils because they are is simply too hot. They don them when strangers appear.

Bedouin Music, Entertainment and Culture

At night Bedouin like lay a carpet o the sand and set up and campfire and drink tea and camel milk late into the night. When travelers are around they are invited to share a coffee. Travelers show they have had enough coffee by shaking their cups.

Traditionally Bedouin culture includes traditional music, poetry, dances (like Saas), Festivals feature various Bedouin traditions such as poetry recitation, traditional sword dances, traditional tent knitting and performances of traditional Bedouin musical instruments. Camel riding and camping in the deserts are also popular leisure activities among urbanised Bedouins who live near the desert. [Source: Wikipedia]

Bedouin music features a prominent clarinet, distinctive Bedouin rhythms and chanting. Around a campfire Bedouins may chant songs well into the night. “Al-Huda” is caravan chants were devised to help camels take their minds off their heavy loads. According to one story the songs were so effective that the camels would arrive a the destinations lively and full of strength but when the singing and drumming stopped the dropped dead from fatigue.

Bedouin instruments include drums, single string instruments and recorder-like wind instrument. A Bedouin instrument which dates Biblical times is the “kinnor” .☼

Sheep wool and goat hair is woven into tents, carpets and blankets by women. Important artistic expressions of design, color and patterns is incorporated into these handicrafts.

Bedouin Literature and Poetry

Oral poetry was the most popular art form among Bedouins. Having a poet in one's tribe was highly regarded in society. In addition to serving as a form of art, poetry was used as a means of conveying information and social control.

Bedouins produce poetry and value oral skills among both men and women. Bedouin poems include advice to children, messages to lovers and enemies, self-deprecating dances, accounts of battles, and accounts of historical events. These poems have traditionally been recited around campfires at night along with folk tales and stories from Koran that sometimes give Mohammed supernatural powers,

Bedouin poems are often unique to the tribe, with tribes only a few kilometers away not knowing the verses of their neighbors. Since Bedouins were illiterate until relatively recently, their poetry, literature, history and traditions were passed on orally from one generation to the next.

Book: “Bedouin Poetry of the Sinai and the Negev” by Clinton Bailey (Clarendon Press, Oxford University)

Bedouin Education and Health

Some Bedouins can not read or write and have never spent a day in a school. However, Shamika A. Mitchell, Ph.D. of Rockland Community College, State University of New York, said: “It is widely known that Muslims are required to learn the Qur'an" and since "the majority of Bedouins are Muslim there is a likelihood that literacy (at least for men & boys) is somewhat normal.” It is possible that “they don't learn to read the Qur'an, and that they learn through oral memorization.”

Bedouins that are 35 to 40 often look 50 or 60, a result of a hard life and exposure to the sun and dry air. Illness is attributed to imbalances of elements, the presence of evil spirits and germs.

A doctor who worked with Bedouins told National Geographic, "The most common problem is respiratory infection, because they live outside without proper housing in the winter. And their diet is mostly milk, meat, rice, some bread, and dates — no fresh fruit or vegetables."

Treatments include modern medicine, herbal remedies, branding and the wearing of amulets, often with Koranic scriptures inside. Bedouins with heart trouble are sometimes treated with cigarette burns to the chests, a common folk remedy. Some Bedouins receive medical care from doctors that visit remote regions by plane. ☼

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources:”History of Arab People” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong (Modern Library, 2000); National Geographic articles about the Middle East; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2019