BEDOUIN HOMES AND CAMPS

Bedouins have traditionally eschewed permanent homes. preferring portable tents or shelters that give them the flexibility to move around with their animals. Bedouins that return to the same place every year for the winter months often build stone houses. A typical Bedouin house contains a sitting room, kitchen, sleeping quarters, women’s quarters and a courtyard for animals. Around the houses are buildings with ceilings, walls and fences made of bastani, palm fronds. A Bedouin "apartment" is a house size bolder with enough of a overhang to provide shade from the mid day sun.☻

Bedouin houses and tents are typically divided into two, sometimes three sections, with one section for women — also containing a kitchen and storage areas — and another section for men and visitors, where men gather and hospitality is offered to guest, kin and business associates. The third section is for sick or where very young animals are taken care of. These days the winter camps are often at least partially occupied the entire year with the young and old remaining behind to take advantage of government-sponsored education and health care

Bedouins have traditionally migrated in in-law-related domestic units or households in the spring and summer and converged with other near-kin households to live in bigger camps in the winter. The size of camp can vary between three tents or as many as 15. The size of the camp is often dependant on how much pasture is available for animals. The deserts can be quite cold at night. Bedouins build fires at night to keep warm.

Bedouins set up their camps near a water source, usually a well. Only tribes that own the well are allowed to draw water from it. You can still find Bedouins who set up their tents in the desert 40 miles from the nearest water.

See Separate Article BEDOUINS factsanddetails.com

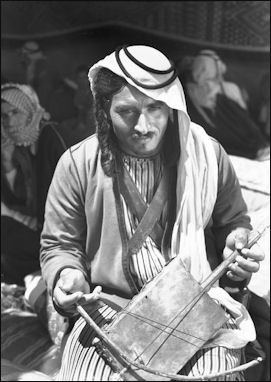

Bedouin Tents and Possessions

Bedouin have traditionally lived in tents known as “buryuut hajar” . (literally “house of hair”). They have traditionally been made black goat-hair and are usually square or rectangular but can be round. They are stretched over a skeleton or supported by a single center pole. There are also canopies used to provide shade at outdoor wedding, funerals and other events. But why are the tents black if black absorbs heat and white reflects it?

The tents are bulky and heavy. Nomads use the tents as a source of shade and a place to store their things. Sometimes they sleep in the tent. Other times they sleep in the open. The tents are easy to move. Many tend to be more like canopies than tents. The top is 20 to 30 feet long. A strip of cloth hangs down the back. On cold nights the front is closed for extra warmth.

Large ones are 40 feet long. The tent of sheik may be a 100 feet long or more and divided into parts by a curtain. One part is for the chief and his guests. Another part is for women children and storage. Patterned draperies, hand-woven from dyed wool and goat’s hair, partitions the harem.

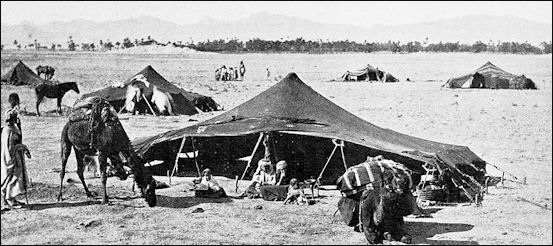

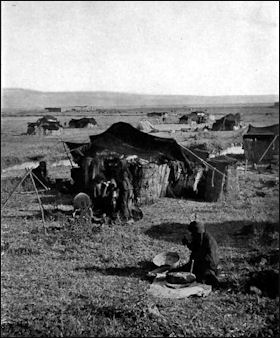

Encampment in the Sahara near the Atlas mountains

A variety of fabrics in bright colors are used for the tent linings. Traditional tents sold in Cairo have a hand-stitched applique designs in Islamic or Pharonic style. A bottom-of-the line unlined 6-by-9-foot tent goes or a little as $80. A made-to-order 8-by-16-foot model with hand-stitched cloth goes for around $250. Tent shops in Cairo are located off Tentmaker's Street. [Source: Douglas Jehl, New York Times]

Typical Bedouin possessions include pillows, carpets, goat hair mats died with henna, and heaps of cushions. People sleep on cotton quilts. Carpets are placed on the sand. Large amounts of possessions are frowned up because that translates to additional weight that is carried when the Bedouins are on the move. A family may keep some pots and pans. China and glassware might break. In some places solar-powered refrigerators are carried on the backs of camels filled with vaccine for remote areas.

Describing the inside of Bedouin tent Abercrombie wrote: "Tattered carpets covered the earth floor around the hearth; a gunnysack partition separated us from the women's quarters. A crude wooden chest held cups and a kerosene lamp. Through an open flap I saw Khalaf's herd, a hundred or more camels, grazing along the southern horizon."

Bedouin Nomadic Life

Nomadic life revolves around reaching for food for their animals. Bedouins have traditionally followed more or less regular movement throughout the year with migration patterns determined by seasonal conditions, amounts of pasture and access to water. Pastures are generally distributed in a regular fashion in accordance with the seasons. When rain is plentiful (i.e. a few inches a year) grass and sedge sprout between dunes.

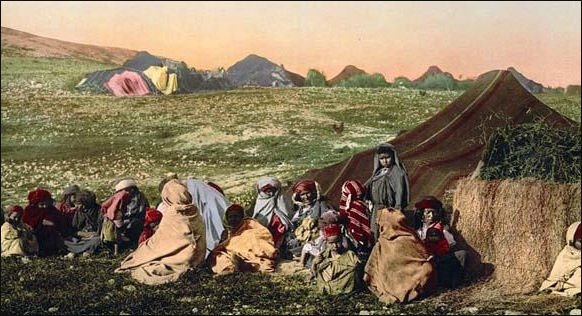

Bedouins in Tunisia 1899

Bedouins have traditionally eked out a meager living on the perimeters of the desert, the margins of cultivated areas, coastal plains and highland pastures, grazing their animals. During the spring and winter they venture into the desert when seasonal rains briefly bring make the desert bloom. Nomads set up their tents and stay in a certain areas as long as there is food for their animals. If there are no rains there is no gazing land for the animals and thus no milk for food.

Explaining the appeal of the nomadic life, one Bedouin nomad told National Geographic: “You are free. You have a relationship only with your animals. The only relationship more important is with Allah.” Otherwise it is a tough life. T.E. Lawrence once wrote that nomadism was “the most deeply biting of all social disciplines...a life too hard for all but the strongest and most determined.”

Bedouins often travel at night because it easier navigate under the stars People looking for Bedouins sometimes have to spend several weeks to locate them wandering in the desert. "For us the desert is neither fearsome nor mysterious," a Bedouin desert policeman told Abercrombie. "It is home. We know the barren hills, each bitter stretch between wells. We understand its signs and its people.

Bedouins have traditionally wandered the desert in search of water. Now many Bedouin settle in one place and drill for water. In many places trucks have replaced camels as the beast of burden. These days truck are often used to bring feed and water for herds in the desert.

Nomad, Herder and Livestock Migrations

Herders have traditionally moved their animals between the high summer pastures of the mountains and their villages camps on steppes where they spend the winter. They pick up and move two or three times a year, typically in May and October, usually remaining within a 25-square mile area, and relocate from November to April in a winter camp with some stone shelters for the animals.

Herders will stay in an area as long as the there is enough grass. Where grazing land is more scarce nomads roam across large swaths of empty plains, mountains and grassland, having to travel longer distances and pack up and move maybe ten or so times a year or as often as twice a week. Moving the animals around also allows the grass to grow back.

There are no fences, except around cities, Herders have traditionally takes their animals to where the pastures were best. In the dusty steppes and sandy deserts they find places where wild grasses grow tall and find places in the mountains were the pastures are sweet.

In some cultures men ride on horses and women and ride on horseback or on the pack animals. Camels have traditionally been used to move possessions, with everything loaded on their backs: tent parts, carpets, pots and pans, shelves, stoves. These days trucks often fulfill this duty.

It takes a nomad around two weeks to slowly move his animals, which graze along the way, 100 kilometers. The nomads don’t need maps and GPS devices; they use the sun, stars, the shape of hills and mountains and landmarks to find their way.

Seasonal Migrations

Bedouin tents 1912 The pastures are divided according to season’summer, spring/fall, and winter based on the amount of grass and when the grass is sufficient to eat, which is often determined by geography, climate conditions and season. The summer pastures are usually located in the north in the steppe areas or in the mountains. These areas have abundant, lush grass but heavy snows made it impossible for the animals to graze. In the winter the animals are taken to the south to the desert and semidesert zones, where autumn rains are imperative for producing grass for animals to eat.

Mountain-dwelling Bedouins in Morocco practice transhumance, migrating between winter camping areas in the valleys, where they sometimes plant grain, and moving their livestock to highland pastures in the summer. Groups that live near mountains migrate between the high pastures in the summer and the river valleys in the winter. The distance between pastures and the river valleys is often less than 50 miles. When the conditions are favorable large groups sometimes set up their tents together in the open pastures and gather for circumcision ceremonies, weddings, funerals, festivals and family reunions that often feature dancers and animal races.

During the hottest months of summer Bedouin's have traditionally made their way to oases, towns or cities and camp on the outskirts of these places where they sell some of their animals and use what little money they earn to buy rice, wheat, tea, coffee and other things.

The main migrations are between summer and winter pastures. Between them nomads stay briefly at fall and spring pastures. Nomads that move overland between the northern steppes and the southern semideserts are known as “meridanal” nomads while those that migrate up and own the mountains were called “vertical” nomads. The nature of the migration, the type of grass available and the market price for animals and family and clan needs determine which animals are raised.

In areas where rainfall is relatively reliable, such as Badia and Nejd in Arabia and Sudan, Egypt, southern Tunisia and Libya, Bedouins move their animals to place where pasture is regularly found. Often these groups plant grain along the migration routes, which they harvest when they return to their winter camping areas.

Nomadic Bedouins on the Move

When the grass and shrubs in a certain are have been consumed or when they area ready to head from towns and oases to the desert Bedouins break down and roll up their tents and load up their possessions on their camels and move on to place with food for their animals. Water is carried for people and the smaller animals. Camels are taken to a trough and encouraged to drink as much as possible before the trek begins.

Nomads on the move often sleep in the open unless there is severe weather because setting up and breaking down the tents is too consuming. In the old days heavily armed advance groups went ahead on fast camels to offer protection against attacks from bandits. They were followed by pack animals and sometimes camels with litters (wooden platforms with loop holes projecting from each side) that carried women and children.

Bedouin animals need pasture and water. They are rarely in the same places. Life revolves around going between the wells and the pastures. Sometimes it is a several day journey between the two. When Bedouins see a dark cloud in the distance they often move their animals there because they know there is chance the cloud will bring rain, grass and water.

Semi-Nomadic and Settled Bedouins

Most Bedouins now live a settled life, although they keep the customs of their nomadic ancestors. In some places Bedouins have been forced by their government to give up their nomadic ways and moved into concrete house villages. Sometimes they have chosen to live a settled life to get jobs and earn money.

Many Middle Eastern countries governments have encouraged the Bedouins to settle down and outlawed raiding. They have offered Bedouins free seed, housing and cash bonuses if they settle down. Wells have been drilled in wadis and small farms have been set up. During droughts water is brought in on huge Mercedes tanker trucks that plow a wide track through the sand. When the truck pulls up all the camels gather around and drink from a makeshift trough made from oil drums. Bedouins are grateful for secure food and water supplies but missed the nomadic life.

Many Bedouins spend part of the year migrating with their goats, and some time harvesting dates, cultivating grain, or growing vegetables. Bedouins in villages say they like access to clinics and schools but don't like the concrete houses. Some use their houses for storage and sleep in the open. Many live in them only part of the year and head out to the desert with their flocks when the weather is right.

These days when weather is good they can wander where they want. When the weather is bad they stay near cities and towns. In the old days when rains and food gave out Bedouins raided farms. In some places Bedouins have caused severe overgrazing.

Bedouin Economics and Agriculture

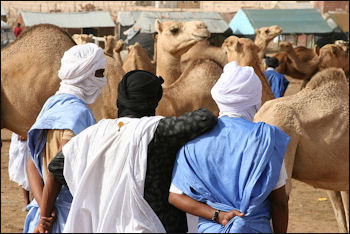

Nouakchott camel market Bedouin have traditionally been mostly self sufficient, getting most of what the need from their animals. But they also need food like wheat, other cereals and dates to survive and traditionally have traded meat, milk products, hides and animals with sedentary people for grain and dates and things they could no produce themselves. Bedouins have traditionally acquired things like kettles, saddlebags, swords, raw wool, mousetraps, tambourines, coffee, ropes, and black tents with occasional trips into town souks.

Sometimes trade is conducted in the desert. Occasionally traders enter Bedouin camps and brand the animals they want to buy and pick them up at the end of the season. In some regions, traveling Gypsy tinkers and traders provided Bedouins with services and goods they need.

In the old days, many Bedouins made a living raiding villages and exacted protection money. An extortion-raid agreement was typically worked out like a business deal with villagers providing the Bedouins with grain. These days many Bdouins are involved in smuggling. Sinai Bedouins are known for smuggling drugs into Israel.

Bedouin groups have traditionally sought to control or at least have access to land, water and other resources they need to sustain themselves. Each group has access to particular zones and limits and rights to these zone are worked out among the groups that occupy a given region. Only during emergencies will a group use land and resources that are not theirs and this generally only occurs after long negotiations with the group that controls the land or resources. This system has been undermined by the creation of nation-sates and governments that do not recognize Bedouin traditional land rights. Most Bedouins today live on “state-owned” land.

Bedouin have traditionally regarded it as beneath to practice farming. In the old days they sometimes got slaves to do their farming for them. Today some Bedouins raise their own crops. Others have access to small date gardens for short periods of time. Typically these Bedouins rent oasis or agricultural land under an agreement that allows them to harvest food produced on that land. Camels skulls sometimes used as scarecrows.

Bedouin Labor

Traditional division of labor has been largely defined by which animals are raised, with men typically caring for the large animals, particularly camels, and women being responsible for the smaller animals such as goats and sheep. Women are often prohibited from having close contact with camels and other large animals. They and older girls spend much of their time herding, feeding and milking When only sheep and goats are kept, men tend to do the herding and women do the feeding and milking.

Bedouins works as oil drillers, truck drivers, shopkeepers and farmers. These days many Bedouins do odd jobs and return to their nomadic ways when jobs are scarce. In Saudi Arabia, once proud “noble” camel herding Bedouins now serve in the Saudi National Guard or work as laborers. In Syria, Egypt and Iran land reform measures and new patterns of land use have forced nomads to become integrated into they money economy. Syria offers free farmland to Bedouin tribal chiefs to encourage the nomads to settle down.

Bedouins are often hired as trackers to track down smugglers or find tourist who got lost in the desert. Trackers can see a track in a region that otherwise looks like untouched sand dunes. When asked how they do it they say it’s a sixth sense. Sometimes they find their way on a trail marked by dead camels.

Before GPS, professional Bedouin trackers were hired by oil companies to help geologist navigate through featureless desert expanses. Describing a one such tracker Thomas Abercrombie wrote in National Geographic: “Jabr was lean but tough as leather. He brought with him all his worldly goods: a turban, short white gown, cartridge belt, and rifle. He kept his fair in long ringlets and his black beard trimmed short, and he looked the world straight in the eye.”

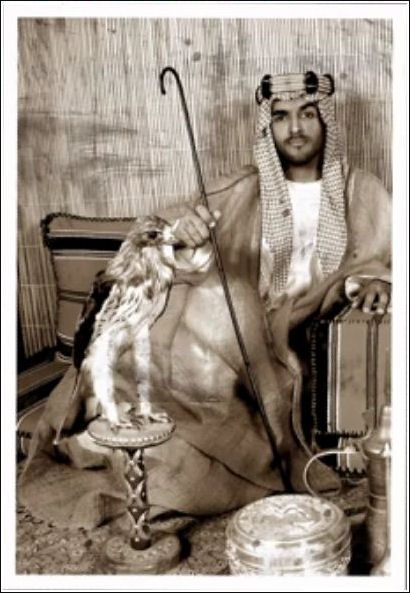

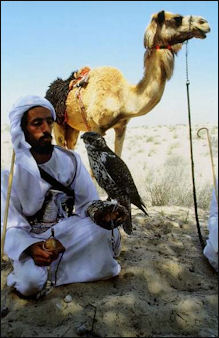

Bedouin Livestock

Syrian Bedouin shepherd Livestock raising had traditionally been the primary economic activity of Bedouins. Among Bedouins livestock has traditionally been a measure a wealth and a means os survival. A Bedouin’s riches are measured in his goats, sheep and camels that produce dividends of milk, wool and meat.

Camels and horses are the most valuable animals, followed by donkeys, sheep and goats. A chief may posses more than a thousand camels. An ordinary herder may only own two or three camels. Grazing land and water have traditionally been regarded as the common property of all those who used them.

Camels supply food transport and clothing. Flocks of sheep and goats are also kept. Nomad animals provide milk, meat, hides and or wool for cloth. The hides of dead animals are used to make sandals, water bags and other items.

Bedouins have more than 160 words for camels, "depending on age, sex, color, bloodline." Bedouins brand their camels and often put graffiti with triangular camels with a the tribal mark inside the hump.

See Nomads and Migrations

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, The Louvre, The British Museum

Text Sources:”History of Arab People” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong (Modern Library, 2000); National Geographic articles about the Middle East; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2012