GLOBAL WARMING AND THE SEA

giant jellyfish off Japan

maybe connected to global warming Global warming is causing ocean temperatures as well as air temperatures to rise. The ocean has absorbed about 90 percent of the excess heat from global warming, raising average ocean temperatures by roughly 1.8°F (1°C) over the past century, according to NASA. This warming has driven a 50 percent increase in surface marine heat waves in just the last decade. A 2005 report by a team headed by Tim Barett of Scripps Institution of Oceanography found that between 1955 and 2000, the oceans warmed by 0.7 degrees F. Because the oceans are so vast the energy needed to warm them even smalls amount is huge.

Sea temperature plays a critical role in the life of marine species and warming oceans are causing widespread and severe impacts. Globally, the average air temperature of the Earth’s surface has warmed by over 1 degree Celsius since reliable records began in 1850. Each decade since 1980 has been warmer than the last, with 2010–19 being around 0.2 degrees Celsius warmer than 2000–09. Sea surface temperatures are increasing too, as over 90 percent of the excess heat gained in the atmosphere from enhanced greenhouse warming is going directly into the oceans. [Source: Australian government]

Scientist have been surprised how even water at great depths is warming up. Water surface temperatures in the tropical Northern Hemisphere have increased at ten times the rate of global warming in the air since 1984. Increases of .5 degree to 1 degree F have occurred in the major hurricane and typhoon breeding areas in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans since 1906.

Carbon dioxide moves freely between the air and sea in a process known as molecular diffusion and tend to go where concentrations are the lowest. When carbon dioxide of levels are high in the air it flows into the sea. It is thought that carbon dioxide used moved from the seas to the air but now the situation is reserved and its flowing from the air to the seas. Some people have proposed pumping excess carbon dioxide into the deep sea but these plans were dropped when it was discovered that large doses of carbon dioxide kill marine life immediately

A number of Earth-orbiting satellites routinely provides updates on sea surface temperatures, sea level changes and ocean winds. Some have asked is it possible for heat from inside the Earth to heat up the seas, If that was happening the seas would heat up from the bottom up. There is no indication that that is happening. Most of the warming occurs at the surface.

Related Articles:

CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACT ON THE OCEAN: WARMER SEAS, CHANGING COLORS, FISH, CURRENTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

HUMANS AND THE OCEANS: MYTHS, PRODUCTS, ETIQUETTE AND DRUGS ioa.factsanddetails.com

POLLUTION IN THE SEA ioa.factsanddetails.com

RED TIDES (HARMFUL ALGAL BLOOMS): DEAD ZONES, EUTROPHICATION, CAUSES AND IMPACTS ioa.factsanddetails.com

OCEAN ACIDIFICATION ioa.factsanddetails.com ;

ENDANGERED CORAL REEFS AND THEIR RECOVERY AND REBIRTH ioa.factsanddetails.com

GLOBAL WARMING AND CORAL REEFS ioa.factsanddetails.com

CORAL BLEACHING: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND RECOVERY ioa.factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Climate and the Oceans” (Princeton Primers in Climate) by Geoffrey K. Vallis Amazon.com

“The Encyclopedia of Weather and Climate Change: A Complete Visual Guide”

by Juliane L. Fry, Hans-F Graf, et al. Amazon.com

“Atmosphere, Ocean and Climate Dynamics: An Introductory Text” (International Geophysics by John Marshall, R. Alan Plumb Amazon.com

“Great Ocean Conveyor: Discovering the Trigger for Abrupt Climate Change”

by Wally Broecker Amazon.com

“Beyond Extinction: The Eternal Ocean―Climate Change & the Continuity of Life”

by Wolfgang Grulke Amazon.com

“The Unnatural History of the Sea” by Callum Roberts (Island Press (2009) Amazon.com

“The Ocean of Life: The Fate of Man and the Sea” by Callum Roberts Amazon.com

“Plastic Soup: An Atlas of Ocean Pollution” by Michiel Roscam Abbing Amazon.com

“Blue Hope: Exploring and Caring for Earth's Magnificent Ocean” by Sylvia Earle (2014) Amazon.com

“The Empty Ocean” by Richard Ellis (2003) Amazon.com

“Oceans: The Threats to Our Seas and What You Can Do to Turn the Tide” by , Jon Bowermaster (2010) Amazon.com

“Dark Side of The Ocean: The Destruction of Our Seas, Why It Maters, and What We Can Do About It” by Albert Bates Amazon.com

“Ocean's End: Travels Through Endangered Seas” (2001)

by Colin Woodard Amazon.com

“The Blue Machine: How the Ocean Works” by Helen Czerski, explains how the ocean influences our world and how it functions. Amazon.com

“The Science of the Ocean: The Secrets of the Seas Revealed” by DK (2020) Amazon.com

“Atmospheric and Oceanic Fluid Dynamics: Fundamentals and Large-Scale Circulation” by Geoffrey K. Vallis (2006) Amazon.com

“Essentials of Oceanography” by Alam Trujillo and Harold Thurman Amazon.com

“Ocean: The World's Last Wilderness Revealed” by Robert Dinwiddie , Philip Eales, et al. (2008) Amazon.com

High Ocean Temperatures

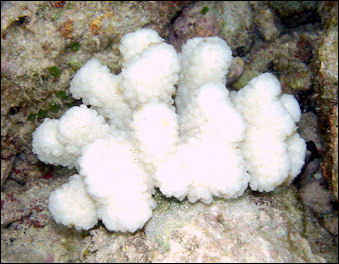

Bleached coral Global ocean temperatures are surging to unprecedented levels, with about 40 percent of the world’s oceans in marine heat waves in 2023, the highest share since satellite records began in 1991. NOAA scientists said temperatures rose up to 50 percent by September 2023, with extreme warming persisting through the end of the year. Sea surface temperatures outside the polar regions broke monthly records since March 2023, with global averages reaching their highest levels since at least 1850. Scientists warn the spike is fueled primarily by human-driven climate change, compounded by natural climate patterns such as a weakened Bermuda/Azores High, reduced Saharan dust, and the onset of El Niño.[Source: Dinah Voyles Pulver, USA TODAY, July 5, 2023; Victor Tangermann, Futurism, May 4, 2023]

Researchers are alarmed: In 2023, heat wave conditions lingered through late 2023 across the tropical Atlantic, Northeast Pacific, and equatorial Pacific. Daily global sea surface temperatures set new all-time highs for over a month and show “no sign of settling.” Studies indicate Earth has absorbed nearly as much heat from 2008 to 2023 years as in the 45 years before that, suggesting the climate system is entering a period of rapid, poorly understood acceleration. Many scientists warn we are only at the beginning of these intensifying trends.

The hottest ocean temperatures in history were recorded in 2021 — the sixth consecutive year that this record has been broken. Despite an La Niña event, which cools cools waters in the Pacific, 2021 set a heat record for the top 2,000 meters of all oceans around the world,. Modern record-keeping for global ocean temperatures began in 1955. The second hottest year for oceans was 2020, while the third hottest was 2019.[Source: Oliver Milman, The Guardian, January 11, 2022]

“The ocean heat content is relentlessly increasing, globally, and this is a primary indicator of human-induced climate change,” said Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Colorado and co-author of the research, published in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. “The heating trend is so pronounced it’s clear to ascertain the fingerprint of human influence in just four years of records, according to John Abraham, another of the study’s co-authors. “Ocean heat content is one of the best indicators of climate change,” added Abraham, an expert in thermal sciences at University of St Thomas.

According to The Guardian: “The amount of heat soaked up by the oceans is enormous. In 2021, the upper 2,000 meters of the ocean, where most of the warming occurs, absorbed 14 more zettajoules (a unit of electrical energy equal to one sextillion joules) than it did in 2020. This amount of extra energy is 145 times greater than the world’s entire electricity generation which, by comparison, is about half of a zettajoule.

Oceans and Carbon Dioxide

Acting as a large sponge, oceans absorb about a third of the carbon dioxide that humans produce. If it wasn’t for the oceans the Earth could be two degrees warmer rather than one degree it is now. A study published in Science in July 2004 that involves analyzing 70,000 samples taken from around the globe in the 1990s reported that 48 percent of carbons dioxide produced by humans from 1800 and 1994 — 467 billion tons of the gas — had been absorbed by seawater. Not only that the oceans have produced much of the oxygen we breath.

By some estimates carbon dioxide is entering the ocean at a rate of 1 million tons an hour, ten times the natural rate. There is a large concentration of carbon dioxide in the Atlantic Ocean between North America and Europe and North Africa. The concentrations of carbon dioxide here are around 1.2 kilograms per meter, double or quadruple the amounts in most other seas. The North Atlantic Ocean holds the most because that is where cooled surface water sinks, filling more of the water column with carbon.

Elizabeth Kolbert wrote in National Geographic, “The air and the water constantly exchange gases, so a portion of anything emitted into the atmosphere eventually ends up in the sea. Winds quickly mix it into the top few hundred feet, and over centuries currents spread it through the ocean depths. In the 1990s an international team of scientists undertook a massive research project that involved collecting and analyzing more than 77,000 seawater samples from different depths and locations around the world. The work took 15 years. It showed that the oceans have absorbed 30 percent of the CO2 released by humans over the past two centuries. They continue to absorb roughly a million tons every hour. [Source: Elizabeth Kolbert, National Geographic, April 2011]

Robert Stewart wrote in “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”: Two aspects of the deep circulation are especially important for understanding earth’s climate and its possible response to increased carbon dioxide CO2 in the atmosphere: A) the ability of cold water to store CO2 and heat absorbed from the atmosphere, and B) the ability of deep currents to modulate the heat transported from the tropics to high latitudes. [Source: Robert Stewart, “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”, Texas A&M University, 2008]

The ocean is the primary reservoir of readily available CO2. The ocean contain 40,000 GtC ((gigatonnes of carbon) of dissolved, particulate, and living forms of carbon. The land contains 2,200 GtC, and the atmosphere contains only 750 GtC. Thus the ocean hold 50 times more carbon than the air. Furthermore, the amount of new carbon put into the atmosphere since the industrial revolution, 150 GtC, is less than the amount of carbon cycled through the marine ecosystem in five years. (1 GtC = 1 gigaton of carbon = 1012 kilograms of carbon.) Carbonate rocks such as limestone, the shells of marine animals, and coral are other, much larger, reservoirs. But this carbon is locked up. It cannot be easily exchanged with carbon in other reservoirs.

More CO2 dissolves in cold water than in warm water. Just imagine shaking and opening a hot can of CokeTM. The CO2 from a hot can will spew out far faster than from a cold can. Thus the cold deep water in the ocean is the major reservoir of dissolved CO2 in the ocean. New CO2 is released into the atmosphere when fossil fuels and trees are burned. Very quickly, 48 percent of the CO2 released into the atmosphere dissolves into the ocean (Sabine et al, 2004), much of which ends up deep in the ocean. Forecasts of future climate change depend strongly on how much CO2 is stored in the ocean and for how long. If little is stored, or if it is stored and later released into the atmosphere, the concentration in the atmosphere will change, modulating earth’s long-wave radiation balance.

Role of the Ocean in Ice-Age Climate Change

According to the “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”: “What might happen if the production of deep water in the Atlantic is shut off? Information contained in Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, in north Atlantic sediments, and in lake sediments provide important clues.

Several ice cores through the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets provide a continuous record of atmospheric conditions over Greenland and Antarctica extending back more than 700,000 years before the present in some cores. Annual layers in the core are counted to get age. Deeper in the core, where annual layers are hard to see, age is calculated from depth and from dust layers from well-dated volcanic eruptions. Oxygen-isotope ratios of the ice give air temperature at the glacier surface when the ice was formed. Deuterium concentrations give ocean-surface temperature at the moisture source region. Bubbles in the ice give atmospheric CO2 and methane concentration. Pollen, chemical composition, and particles give information about volcanic eruptions, wind speed, and direction. Thickness of annual layers gives snow accumulation rates. And isotopes of some elements give solar and cosmic ray activity (Alley, 2000). [Source: Robert Stewart, “Introduction to Physical Oceanography”, Texas A&M University, 2008]

Cores through deep-sea sediments in the north Atlantic made by the Ocean Drilling Program give information about i) surface and deep temperatures and salinity at the location of above the core, ii) the production of north Atlantic deep water, iii) ice volume in glaciers, and iv) production of icebergs. Ice-sheet and deep-sea cores have allowed reconstructions of climate for the past few hundred thousand years.

The oxygen-isotope and deuterium records in the ice cores show abrupt climate variability many times over the past 700,000 years. Many times during the last ice age temperatures near Greenland warmed rapidly over periods of 1–100 years, followed by gradual cooling over longer periods. For example, around 11, 500 years ago, temperatures over Greenland warmed by ≈ 8 degrees C in 40 years in three steps, each spanning 5 years. Such abrupt warming is called a Dansgaard/Oeschger event. Other studies have shown that much of the northern hemisphere warmed and cooled in phase with temperatures calculated from the ice core.

The climate of the past 8,000 years was constant with very little variability. Our perception of climate change is thus based on highly unusual circumstances. All of recorded history has been during a period of warm and stable climate. Hartmut Heinrich and colleagues (Bond et al. 1992), studying the sediments in the north Atlantic found periods when coarse material was deposited on the bottom in mid ocean. Only icebergs can carry such material out to sea, and the find indicated times when large numbers of icebergs were released into the north Atlantic. These are now called Heinrich events.

The correlation of Greenland temperature with iceberg production is related to the deep circulation. When icebergs melted, the surge of fresh water increased the stability of the water column shutting off the production of north Atlantic Deep Water. The shut-off of deep-water formation greatly reduced the northward transport of warm water into the north Atlantic, producing very cold northern hemisphere climate. The melting of the ice pushed the polar front, the boundary between cold and warm water in the north Atlantic further south than its present position. The location of the front, and the time it was at different positions can be determined from analysis of bottom sediments.

When the meridional overturning circulation shuts down, heat normally carried from the south Atlantic to the north Atlantic becomes available to warm the southern hemisphere. This explains the Antarctic warming. The switching on and off of the meridional overturning circulation” can have a large impact. “The circulation has two stable states. The first is the present circulation. In the second, deep water is produced mostly near Antarctica, and upwelling occurs in the far north Pacific (as it does today) and in the far north Atlantic. Once the circulation is shut off, th system switches to the second stable state. The return to normal salinity does not cause the circulation to turn on. Surface waters must become saltier than average for the first state to return. A weakened version of this process with a period of about 1000 years may be modulating present-day climate in the north Atlantic, and it may have been responsible for the Little Ice Age from 1100 to 1800.

Ocean Sponges Suggest the Earth Has Warmed Earlier and Longer than Thought

A study published in Nature Climate Change in February 2024 suggests that human-driven climate change may have begun earlier—and warmed the planet more—than previously believed. By analyzing growth records from six long-lived Caribbean sponges, researchers reconstructed ocean temperatures, acidity, and atmospheric CO levels dating back to the 1800s. Their findings, indicate that the pre-industrial world was about 0.5°C cooler than current estimates and that warming began around the mid-1800s, not the early 1900s. This would mean global warming had already reached about 1.7°C by 2020—surpassing the 1.5°C threshold that countries aim to avoid. [Source: Seth Borenstein, Associated Press February 6, 2024]

If correct, scientists warn, the world has a decade less time to cut emissions than previously thought. The results could also help explain why recent extreme weather has exceeded expectations for current warming levels.

However, many climate scientists are skeptical, arguing that the findings rely on a small sample of sponges from one region and conflict with global instrumental records. Skeptics say the study may overstate warming or underestimate uncertainties, though they acknowledge sponges can provide valuable environmental records.

The researchers defend their methods, noting that sponge-based reconstructions match other climate proxies—such as coral and ice cores—outside the 1800s. They say sponges may be more accurate than early ship-based temperature measurements, which were prone to error.

Even with debate over its conclusions, the team stresses that warming is accelerating, with 2023 pushing global temperature rise to about 1.8°C since pre-industrial times. Lead author Malcolm McCulloch warns that the findings highlight an urgent need to cut emissions: “We are heading into very dangerous high-risk scenarios for the future.”

Greenhouse Gases Hidden in the Oceans That Could Make Climate Change Worse

Scientists are uncovering vast, hidden reservoirs of carbon dioxide and methane sealed beneath the seafloor—stores of potent greenhouse gases locked in place by icy caps called hydrates. As the oceans warm, those hydrates are edging dangerously close to melting, raising alarms about a potential climate “time bomb.” These frozen caps trap CO and methane in a strange, ice-like state. But seawater temperatures in some regions are now within a few degrees of destabilizing them. If the caps fail, the ocean—currently Earth’s largest carbon sink—could flip into a massive carbon emitter. CO persists in the atmosphere for millennia, and methane, though shorter-lived, is more than 80 times stronger than CO over 20 years. [Source: Todd Woody, National Geographic, December 17, 2019]

“The oceans absorb a third of our carbon dioxide emissions and most of the excess heat. If these hydrates melt, the consequences could be profound,” paleoceanographer Lowell Stott of USC told National Geographic. The discovery of these reservoirs comes just as scientists warn that several global climate tipping points may already be underway, with ocean temperatures at record highs.

So far, CO hydrates have been detected around deep-sea hydrothermal vent fields, but their global extent is unknown. Stott believes the world’s carbon budget may be significantly underestimated. Other scientists, like Woods Hole geochemist Jeffrey Seewald, caution that large CO accumulations may be relatively rare—though they emphasize that deep-sea vents remain poorly surveyed.

Closer to shore, however, lies a more immediate danger: methane hydrates scattered widely along continental margins. These shallower deposits are far more vulnerable to warming. Between 2016 and 2018, NOAA and Oregon State University researchers identified more than 1,000 methane seeps off the Pacific Northwest—ten times the number known only a few years earlier. And less than half the region’s seafloor has been mapped.

“Because so much methane is stored in shallow sediments, warming will reach it sooner,” says NOAA scientist Dave Butterfield. Destabilization could release methane to the atmosphere, accelerating global warming. These reservoirs are believed to represent a much larger greenhouse gas store than the deep-ocean CO pools.

Evidence from the geologic past heightens concern. Stott and colleagues recently showed that bursts of CO from seafloor reservoirs helped end the last ice age, and similar patterns appear in sediments near New Zealand. The rapid warming seen during those transitions mirrors today’s temperature spike.

One reservoir of liquid CO discovered by Butterfield’s team on a Pacific volcano was releasing carbon at a rate equal to 0.1 percent of emissions along the entire Mid-Ocean Ridge—an enormous figure for a single small site. Scientists think such reservoirs form when carbon-rich hydrothermal fluids rise and cool, forming hydrate caps that trap the gases in underlying sediments. Their risk depends on depth and water circulation. A known liquid CO lake in Japan’s Okinawa Trough, for example, could be exposed if its hydrate layer melts. While the gas might acidify local waters, it would take a long time to reach the atmosphere due to the lack of upwelling currents.

Finding these reservoirs remains “a needle in a haystack” challenge, Stott says. But new seismic imaging techniques are beginning to reveal more of them. In August, researchers from Japan and Indonesia reported five previously unknown CO or methane reservoirs beneath the Okinawa Trough, identified by how seismic waves slowed as they passed through gas. “Our survey area is small,” says Kyushu University geophysicist Takeshi Tsuji. “There could be more reservoirs beyond it.” And because gases in this hydrothermal zone are unstable, he warns, leakage to the seafloor—and potentially the atmosphere—is a real possibility.

Global Warming and Sea Life

Marine life absorbs about 2 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere a year. Much of the world’s carbon stocks are held in plankton, mangroves, salt marshes and other marine life. Algae in the sea absorbs some of the excessive carbon dioxide but most of it never reach the seabed to become a permanent store. Mangrove forest, salt marshes and sea grass bed cover less than 1 percent of the world’s seabed but they lock away well over half of all carbon absorbed by marine life.

Some underwater creatures such as mussels and freshwater snails emit nitrous oxide, better known as laughing gas — a powerful greenhouse gas that is 310 times more potent than carbon dioxide in trapping heat in the atmosphere.

sea surface temperatures

Carbon dioxide in the air and the seas and warmer sea temperatures result in less oxygen near the surface of the sea and produce oxygen poor zones that extend vertically. The massive dead zones like the on off the west coast of the United States are believed to be caused by global warming and warming sea temperatures and changes between the wind and sea that deprive the water of oxygen. The lack of oxygen will be especially tough on large sea creatures that need lots of oxygen to move around and hunt.

High temperatures have already resulted in the bleaching of coral and disappearance of Arctic ice cover. In the Americas global warming has caused an oyster-infecting bacterium that causes food poisoning in humans to spread from the Gulf of Mexico to waters off Alaska. The high temperatures also stunt growth, reduce food supplies and can force fish to breed in or move to cooler water for which they are not adapted.

Climate change affects turtles, sea snakes and crocodiles because the environmental temperature controls the reptiles’ body temperatures (except for the leatherback turtle). Of all the marine reptiles on the Reef, turtles are the most vulnerable to climate change. The temperature of the sand, where eggs are laid, determines the sex of turtles. Air temperature and sea temperature increases will alter turtle breeding seasons and patterns, egg hatching success and the sex ratio of the populations.

Seabirds are considered to be some of the most vulnerable species to climate change impacts. During frequent or intense El Niño/La Niña-Southern Oscillation events in tropical waters, seabirds have fewer breeding cycles, slowed chick development and reduced nesting success. This is because higher sea temperatures during such events affect the availability of food for seabirds.

Water temperature partly determines the photosynthesis rates for seagrass — an important food source for dugongs and marine turtles. Temperature increases can reduce the efficiency of photosynthesis; however, the extent of this impact may depend on the species' reliance on the light. Temperature also plays a role in seagrass flowering (and thus reproductive) patterns.

Ways to Reduce Climate Change Involving the Sea

There are several ways to reduce climate change involving the sea and human activity there. Christine Todd Whitman and Leon Panetta wrote in Politico: Among these are: “Boost Offshore Renewables: Offshore renewables, like wind and wave energy, can help power the nation while cutting emissions. These sources of clean energy can serve as part of a just and equitable transition by providing economic benefits and abundant electricity to the communities that have suffered the most under climate change [Source: Christine Todd Whitman and Leon Panetta, Politico, January 29, 2022, 3:30 AM.

“Reduce Emissions from Shipping: We also need to look to the ocean to significantly reduce contributors of greenhouse gas emissions, such as maritime shipping, which generates more emissions than airlines. The administration, working with ports and the shipping industry, can implement strategies that will move us to zero-carbon shipping by 2050 to drastically reduce the climate contributions of cargo ships and freighters at sea. Infrastructure improvements at ports, fleet upgrades and alternative fuels can all be part of the effort.

“Rebuild Coastal Ecosystems: By protecting the ocean, we also enable the ocean to protect us through natural climate mitigation. Carbon-rich coastal environments like salt marshes, seagrass meadows and mangrove forests all naturally absorb carbon up to four times more effectively than trees on land. And when we conserve these habitats for their climate benefits, we are also protecting natural coastal infrastructure that will safeguard communities against storms and rising sea levels. This is particularly crucial for supporting marginalized communities, including low-income neighborhoods that were built in flood zones and are on the front lines of the climate crisis.

Another idea that is being considered is collecting large amounts of sea water, electronically separating the salt into positive-charged sodium and negatively-charged chloride. The chloride is removed and the water is placed into the ocean, altering its chemistry . To regain its balance the dissolved carbon dioxide changes into carbonates, creating more rooms for carbon dioxide to be sucked from the air. There are a lot of problems with the chemical: cost, a lack of technology to change sea water and risks to marine life.

Combating Global Warming — By Dumping Iron in the Sea?

Dumping iron in the seas can help transfer carbon from the atmosphere and bury it on the ocean floor for centuries, helping to fight climate change, study released in 2012 suggested. Reuters reported: The report, by an international team of experts, provided a boost for the disputed use of such ocean fertilization for combating global warming. But it failed to answer questions over possible damage to marine life. When dumped into the ocean, the iron can spur growth of tiny plants that carry heat-trapping carbon to the ocean floor when they die, the study said. [Source: Alister Doyle, Reuters, July 19, 2012]

Scientists dumped seven metric tonnes (7.7 tons) of iron sulphate, a vital nutrient for marine plants, into the Southern Ocean in 2004. At least half of the heat-trapping carbon in the resulting bloom of diatoms, a type of algae, sank below 1,000 meters (3,300 feet). “Iron-fertilized diatom blooms may sequester carbon for timescales of centuries in ocean bottom water and for longer in the sediments,” the team from more than a dozen nations wrote in the journal Nature.

Burying carbon in the oceans would help the fight against climate change. The study was the first convincing evidence that carbon, absorbed by algae, can sink to the ocean bed. One doubt about ocean fertilization has been whether the carbon stays in the upper ocean layers, where it can mix back into the air.A dozen previous studies have shown that iron dust can help provoke blooms of algae but were inconclusive about whether it sank.

Using Plankton and Mangroves to Combat Global Warming

One idea is to spread vast amounts of iron compounds in the ocean to promote the growth of phytoplankton, which in turn would feed millions of fish that would die in a boom and bust cycle and sink to bottom and lock up the carbon their tissues. Tests of this theory shows the fish quickly decay releasing any carbon dioxide they might otherwise locked up. Russ George, CEO of Planktos, is investigating how much carbon dioxide plankton soaks up and has suggested growing huge floating fields of plankton to soak up the gas. Planktos has released tons of iron over a 10,000'square area of ocean to see how well plankton grows there. Environmental groups such as Greenpeace and the WWF have opposed the experiment over concerns for the welfare of marine life.

Mangrove roots, like those of other plants, need oxygen. Since estuarine mud contains virtually no oxygen and is highly acidic, they have to extract oxygen from the air. Mangrove roots extract oxygen with above-ground, flange-like pores called lenticels, which are covered with loose waxy cells that allow air in but not water. Some species of mangrove have the lenticels on their prop roots. Others have them on their trunks or have pneumatophores (fingerlike projection that grow up from the organic ooze). A single large tree such as “Sonneratia alba” can produce thousands of rootlike snorels that radiate out in all direction.

Mangroves sit like platforms on the mud. Their roots are imbedded in the mud just deep enough so plants don't wash away. The areal roots also spread out in such a way that act like buttresses. Scientists have determined carbon inputs and outputs of mangrove ecosystems by measuring photosynthesis, sap flow and other process in the leaves of mangrove plants. They have found that mangroves are excellent carbon sinks, or absorbers of carbon dioxide. Research by Jin Eong On, a retired professor of marine and coastal studied in Penang, Malaysia, believes that mangroves may have the highest net productivity of carbon of any natural ecosystem. (About a 100 kilograms per hectare per day) and that as much as a third of this may be exported in the form of organic compounds to mudflats. On’s research has show that much of the carbon ends up in sediments, locked away for thousands of years and that transforming mangroves into shrimp farms can release this carbon dioxide back into the atmosphere 50 times faster than if the mangrove was left undisturbed.

A United Nations task force on mangroves and the environment recommending: 1) setting up a blue carbon fund to help developing countries to protect mangroves as well as rain forests; 2) place a value on mangroves that takes into consideration their value as carbon sinks; and 3) allow coastal and ocean carbon sinks to be traded in same fashion as those for terrestrial forests. Christian Nellemann, an author a United Nations report on the issue, told the Times of London, “There is an urgency to act now to maintain and enhance these carbon sinks. We are losing these crucial ecosystem much faster than rainforests and at the very time we need them. If current trends continue they [mangrove and coastal ecosystems] may be largely lost within a couple of decades.”

See Creating Desert Wetlands Under DESERT AGRICULTURE AND IRRIGATION factsanddetails.com

Image Source: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noaa.gov/ocean and Wikimedia Commons, except giant jellyfish from Hector Garcia blog

Text Sources: Mostly NOAA, National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Natural History magazine, Discover magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2025