ECONOMICS AND DAILY LIFE IN JAPAN

Osaka drug store Japan is very cash oriented. Coins and banknotes account for 15 percent of national income compared to 6 percent in Germany and 3.5 percent in the United States. Credit cards are not as common in Japan as they are in United States. Japanese walk around with large amounts of cash and pay for most things with cash. Before making a large purchase, they are more likely to run to an ATM machine than use a credit card. ATM machines dispense up to $30,000 in yen.

There are almost no checking accounts or paychecks in Japan. Most people get paid though bank transfers to their bank savings accounts and pay bills by making money transfers at a bank, post office or convenience store that cost as much as $5 each. Instead of waiting in line at a bank, most people give their money or papers to receptionist and then sit and relax on a couch until the transaction is finished and are called to a window.

Consumer spending accounts for about 60 percent of Japan’s GDP. An estimated 5 percent of the economy in Japan is off the books. Some of this is done by tax evaders and members of the yakuza.

As of 2007, Japan had a half dozen electronic payment systems using cards waved over a scanner to pay for goods. Cell phones can also be used to make purchases.

The 20 best places to live (based on life expectancy and per capita income (2002): 1) Norway; 2) Sweden; 3) Canada; 4) Belgium; 5) Australia; 6) United States; 7) Iceland; 8) Netherlands; 9) Japan ; 10) Finland; 11) Switzerland; 12) France; 13; United Kingdom; 14) Denmark; 15) Austria; 16) Luxembourg; 17) Germany; 18) Ireland; 19) New Zealand); 20) Italy. [Source: United Nations, Human Development 2002]

Websites and Resources

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de and japan-photo.de ; Google-E-Book: Japan – Why It Works, and Why It Doesn’t: Economics in Everyday Life books.google.com/books ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Family Budgets and Prices stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp Everyday Scenes jun-gifts.com ; Fixed in Life Blog, with Lots of Photos jeromesadou.com ; Photos funzu.com ;

Sites for Expats Japanable site for Expats japanable.com ; That’s Japan thats-japan.com ; Orient Expat Japan orientexpat.com/japan-expat ;Kimi Information Center kimiwillbe.com ;Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report on Japan fco.gov.uk/en/travel-and-living-abroad ; Student Guide to Japan www2.jasso.go.jp/study ; Japan in Your Palm japaninyourpalm.com Japan Post Bank jp-bank.japanpost.jp ;

Links in this Website: BUSINESS CUSTOMS AND PRACTICES IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE CUSTOMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; EVERYDAY LIFE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;URBAN AND RURAL LIFE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources on Economics: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry meti.go.jp/english ; Ministry of Finance of Japan mof.go.jp/english ; Japan Economy News and Blog japaneconomynews.com ; Japan Economy Watch japanjapan.blogspot.com ; Japan Center for Economic Research jcer.or.jp/eng ; Japan Inc. Economic and Business News japaninc.com ; Google E-Book: Japan in the 21st Century, Environment, Economy and Society (2005) books.google.com/books

Hankos

Instead of signing their name, Japanese stamp their name on forms, bank withdrawal slips and letters with a “hanko” (chop, or signature stamp). Without a hanko one can't open a bank account in Japan or register for a university class. One professor told the Los Angeles Times, "I don't exist in this society without my hanko." [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, November 28, 2001]

Hankos are cylinders about the size of a piece of chalk. They have the person’s name carved at one end in Chinese characters and they leave an imprint after being stamped in ink. Everyone from the Emperor to a homeless man living in a park has a hanko, and they are used for everything from finalizing a multi-million-dollar business deal to signing for packages delivered to one’s house.

The average Japanese has five hankos but only one is registered with the government to certify ownership and it is only used on important documents. Since these seals are considered too valuable to carry around, people have other seals to use for things like bank transactions and taking deliveries. Many government documents have several hanko stamps. According one estimate a typical bureaucrats puts his hanko on 100,000 documents in a 25 year career.

Hankos have a 5,000 year history. Signature seals, which operates according the same concept, were used in ancient Mesopotamia and China. Japan's oldest example of writing is a solid-gold hanko dated to A.D. 57.

In the 8th century, only the Emperor was allowed to use a hanko. Later members of the Imperial court and noblemen started using them. The samurai class gained access to them in the Middle Ages. Ordinary Japanese didn't start using them until the Meiji period in the mid-19th century.

Women, Men and Money in Japan

Japanese housewives have traditionally controlled the family's finances. They are careful shoppers and like things fresh. They look out for bargains like everyone else but don’t go in for buying things in large quantities like Americans, partly because they don’t have room in their relatively small houses for a lot of stuff. Women are also some of Japan's most active investors.

Women are the primary money spenders in Japan in part because they have traditionally controlled household finances and have done the shopping while their husbands worked. These days men are starting to spend more as they become more conscious about the way they look and dress and buy grooming products and fashionable clothes and purchase big ticket items like new cars, flat screen televisions, high-tech chairs and home exercising equipment and expensive gifts for their wives.

Expensive Japan

Armani store in Shibuya Tokyo Japan's consumers pay among the highest prices in the world. Melons famously cost as much as $250 each and cherries can go for as much as $240 a box. A movie ticket is around $20; a haircut often costs more than $50; and a taxi ride from Narita airport to downtown Tokyo can be more than $150. Some toilets and refrigerators sell for between $3,000 and $4,000; some small apartments cost more than $1 million.

Tokyo and Osaka consistently top lists of the world's most expensive cities. Four hundred dollar hotel rooms and $500 dinner for two are not unusual. Gasoline cost about $6 a gallon and milk can go for more than $10 a gallon. Some Japanese fly to Hawaii to play golf because its cheaper than playing in Japan even with the plane ticket factored in.

Although they are not as high as they once were, land prices in Tokyo are still among the highest in the world. One office building in downtown can be worth a billion dollars. A simple wood frame house, not much bigger than a shed, or modest apartment can go for $1.5 million. Prime real estate in the Ginza district can go for as much as $18,000 a square foot.

Why prices are so high? One reason is that there are lots middlemen (See Macroeconomics). Another reason is that Japan has many more shops than it needs. More shops mean lower volume which translates to higher prices. In the 1990s about 10 percent of Japanese food was sold in supermarkets compared to 65 percent in the United States. The owner of a small drug store told the New York Times that the wholesale prices at big stores are cheaper than the prices she pays her supplier.

Another reason Japanese products are so expensive is because of the high level of service in Japanese stores. Department stores are filled with service girls and sales people. Purchases are nicely gift wrapped instead of thrown of in a plastic bag. Sometimes Japanese tend to think “expensive is good."

Japan is not as expensive as it used to be. A survey in 2006 found that prices of 29 key food items were lower in Tokyo than they were in New York and London. Many Japanese now do the bulk of their shopping at supermarkets and discount stores and Mom and Pop enterprises are going business and specialty stores are used mainly to buy gifts. For foreigners, Japan is not really expensive once you figure out the cheap places tp buy stuff.

Most expensive cities for expatriates according to the 2008 Mercer Cost of Living survey: 1) Moscow; 2) Tokyo; 3) London; 4) Oslo; 5) Seoul.

Consumer Habits in Japan

Louis Vuitton in Roppongi Tokyo Japanese consumers are notoriously fickle and demanding. Expectations for quality and freshness are arguably the highest in the world. Consumer spending accounts for about 60 percent of Japan’s GDP.

Japanese often chose quality over price. Nice supermarkets that have good quality stuff often do better than ones with everyday low price places. Ken Belson wrote in the New York Times: “Japanese consumers are considered the world’s most discriminating, particularly those who have traveled overseas. Product cycles are short; preferences swing wildly, especially among younger women; and Japanese consumers tend to be fanatical when it comes to quality.”

Japanese prefer smaller, lighter products and are willing to pay high prices for them. They are also willing to spend money for the latest and coolest stuff. By contrast Americans often seem interested most in the lowest price. One young Japanese woman told the New York Times, “It’s much better to buy one good thing and use it carefully than spend money on many cheap things. As I become busier, I don’t have as much time to shop, so I only go to places where I can get good things.”

Japanese can also be fanatical shoppers. They wait in long lines and rush through the doors at opening time to get hard-to-get products or special discounts. Lines of people waiting to get special New Years bags (bags with unseen products marked down by more than 50 percent) can reach a kilometer in length.

Consumer spending makes up nearly 60 percent of Japan’s gross domestic product. Even during bad times first class air line seats and hotels are full and sales are brisk at stores that sell luxury goods.

In one survey most of they Japanese asked said they wanted to spend their money on “hobbies,” “education” and “travel.” In recent years consumers have begun spending more money and a larger share of their income on electronic and communication items like video games, cells phones, MP3 players and flat screen televisions. Buying a car is much lower priority than it once was.

A number of businesses such as health cubs, bars, e-book stores and restaurants charge customers by how long they stay rather than by a membership fee or per item cost. Izakaya pubs charge about $4 per 15 minutes, e-book stores about $1 per 30 minutes and health clubs $5 for 10 on a treadmill.

Consumers are increasingly becoming satisfied with old models they have and are no longer rushing out to buy the newest thing with latest gadgets like they used to. New but out-of-date and no-longer-manufactured models can often be purchased over the Internet for much lower prices than new models bought at appliance stores.

Gift cards that look like crosses between coupons and cash, used in department stores and other retail outlets, are a popular gift items. In the past they had no expiration dates and could be used years after they were given out. Since 2011 that no longer has been the case. A new law that went into effect then allows firms to set time limits on their validity. Under the law cards that were given with no expiration date can becme worthless after a certain amount of time.

Women Shoppers and Young Consumers in Japan

Akemi Natsuyama, an analyst at Hakuhodo Research, told the Los Angeles Times, “female shoppers tend to be careful on how they spend...They also look at quality and shy away from reckless spending.”

These days women in Japan have more buying power than ever. More have jobs with decent pay and they seem more willing to spend what they earn. With them lies some hope that the economy will pick up. Hiroyuki Nitta, an analyst at Nomura research told the Los Angeles Times, “With the rise in female employment women are not earning their own money and spending more on themselves, a key difference from the past.” Perhaps more importantly they are not just out there shopping for clothes and luxury items they also purchasing real estate and stocks and they spend even when the economy is slow.

After decades of economic stagnation and limited job opportunities for the young, older Japanese consumers tend to possess more disposable income. Hisakazu Matsuda, president of Japan Consumer Marketing Research Institute, who has written several books on Japanese consumers, told the New York Times he has a different name for Japanese in their 20s; he calls them the consumption-haters. He estimates that by the time this generation hits their 60s, their habits of frugality will have cost the Japanese economy $420 billion in lost consumption.”There is no other generation like this in the world,” Mr. Matsuda said. “These guys think it’s stupid to spend.” [Source: Martin Fackler, New York Times, October 16, 2010]

Vending Machines in Japan

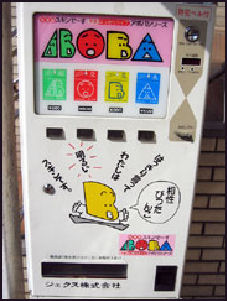

blood type condom

vending machine Vending machines are everywhere in Japan. Not only can you buy candy, juice, cigarettes and soda pop you can also buy hot coffee in cans, cold beer, rice, milk, bottles of scotch, batteries, compact discs, software, panty hose, condoms, beetles, eggs, pornography and even cars. Some offer manicures. Others sell stag beetles, used panties and pearls ranging in price from $39 to $235. Perhaps one reason they are so many is due to the low crime rate and lack of concern about break ins. Teenagers who want to get drunk might consider moving to Japan instead of using a fake ID.

According to the Japan Vending Machine Manufacturers Association there are 5.5 million vending machines, including those that sell ticket, in Japan. There is about 1 vending machine for every 20 people in Japan. About 2.6 million of them sell soft drinks. Japanese vending machines sold about $80 billion worth of products in 2009, 45 percent more than the $42.9 billion in the United States. Sellers like vending machines because it allows them to sell their products at full price, bypassing supermarkets that often demand they be sold at hefty discounts.

An average drink vending machine sells more than 6,000 drinks annually, The drinks typically sell for ¥120 a can, which allows a larger profit than those sold at ¥80 a can at a supermarket. Large vending machines can offer 20 different drinks which often more than a company can sell at convenience stores, which often have very limited shelf space.

About a third of all drinks sold in Japan are sold through vending machines yet the vending machine market is considered saturated. Their numbers peaked at 2.45 million machines nationwide in 2010 and have been declining since then. Because of this drink companies are increasingly forming tie-ups to expand rather than open new machines.

In January 2011, vending machines were installed in central Tokyo that allowed users to purchase gold ingots and gold and silver coins.

A vending machine offering fresh bananas was installed in Shibuya near he trendy 109 fashion complex in 2010 was well received. Selling individual bananas of ¥130 and bunches of ¥390, more than 2,500 bananas were sold the first month.

Vending machines outside train stations dispense cold and hot drink. After the drinks comes down the slot a voice thanks you for our business.

New vending machines offer fresh sushi; warn buyers if certain good haven’t been properly warmed up yet; dispense drinks in cups provided by the user; talk to customers; offer drinks free of charge after earthquakes; scan customers with a camera and tell them what make-up they need; and tel customers the Japanese equivalent of “Have a nice day” or “sorry, I have run out of change” in the Osaka dialect. There are vending machines at museums that dispense miniature art works.

Money Machines in Japan

insurance vending machine In the late 1990s, Japanese banks introduced ATM machines that dispensed clean money. These machine take in wrinkled and dirty yen banknotes, feed them through rollers, heating them to 392̊F and dispense the notes clean, crisp and 90 percent bacteria free. "Virgin money," Evelyn Richards wrote in the Washington Post, "plays an especially key rule at weddings, where cash is the favored gift. No respectable Japanese would give anything but untainted bills."

The clean money machines were invented by Hitachi by accident. In the process of inventing a process to iron out crumbled bills with 392̊F heat, they discovered that the high temperature also kills bacteria. The disinfected cash is especially popular with young women. Explaining why a bank spokesmen said, many "say they don't want to touch things handled by middle-aged men."

In August 2005, Ogaki Kyoritsu Bank, a bank in Gifu Prefecture, introduced “slot machine” ATMs in which users can play games when they do a money transaction. If they win users have their fees waved or win some other prize.

Two types of biometric systems are employed in Japan: one that reads vein patterns in the palm of the hand and another that views patterns on the fingertips. The patterns are stored in a chip embedded in cash used by the user. In 2004, the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi became the first to use biometric identification technology in its ATM machines, employing machines that identify users by the pattern of veins on their palms. Under this system if card is stolen and the pin number is reveled a thief can not use the card.

By the mid 2000s it was becoming common for Japanese to pay for subways and trains using e-money, special cards, credit cards and their cell phones. See Cell Phones

Increasingly cell phones were being used as credit cards or wallets with electronic money functions called osaifu-keitai that allow users to buy things from convenience stores and vending machines and pass through subway and train gates. As of 2005 about 9 million cell phones used had the money function and 28,0000 shops nationwide accepted them. Payments is done through scanners positioned next to the cashier.

Service in Japan

Japanese like service and have traditionally been willing to pay for it. Department stores and health clubs have a lots of extra employees that do little more than say hello and goodby to customers and address their often trivial requests. At service stations employees not only pump the gas, clean the windshield and check the oil, they also empty ashtrays, clean the tires, check the transmission fluid and battery, and shout a hardy "”Irashaimase”!" ("Welcome!") when drivers arrive and stop traffic and direct them out when they leave. When oil companies tried to introduce the idea of self-service stations, Japanese customers initially didn’t go for it. Now there are lots of self-service stations but they have employees standing by if customers need help.

Service in company and government offices is very good. In government offices, generally any person in a department can help you even if you are there at lunch time. Once I found a dead cat on the street outside my apartment and called the local government office and someone came by in 10 minutes to take it away. The service in shops and department stores in generally also very good Unlike the United States, where you often have to search around for somebody to help you, and then they either lack knowledge or have an attitude, in Japan there is usually a lot of eager, friendly and helpful sales staff on hand.

Kimoko Manes, author “Culture Shock of Mind”, sees that American and Japanese attitudes about service related to differences between American individualism and Japanese group mentality in that in the United States individuals tend to worry about their individual concerns and their responsibilities while those of their co-workers are their problem while Japanese tend to see themselves as members of group and each individual in the group is capable and responsible for the demands made on that group.

Carl Kay wrote in “Saying Yes in Japan” that Japanese service is not always great: Japanese businesses provide “elaborate and trivial, even meaningless, services in areas where consumers can help themselves, while failing to provide quality services in areas where consumers require expert assistance.”

In some cases real estate agent will not allow customers to check land until they have paid for it and used-car dealer will not let you take a car for a test drive until you sign a contract. Many bicycle shops will not allow you to try the bikes. You have to go a bike show to ride them.

Hard Work and Being Busy in Japan

Japanese workers really hustle. Garbage collectors, gas station attendants, waitresses and even dental workers and McDonald’s employees run around when they work. One psychologist told the Los Angeles Times, "When Japanese are not working they feel guilty.” Japanese have little patience for people who are lazy, break promises or who do not try their best. They resent poor service as a personal insult.

A great emphasis is put on being busy. Unlike Americans who tend to look at work as a means of reaching a goal, Japanese often regard work as an end to itself, a kind of existential existence. When one goal is reached it time to move on to the next one. Children learn early in school that hard work is a virtue. They like helping out and do so with great enthusiasm and pleasure.

The rich and highly regarded Japanese investor Nobuyuki Koga told the Times of London that Japanese “employees are ambitious, and we are fortunate to have people that naturally work extremely hard. On the one hand, there is also a pioneer spirit that exists...while people really are deeply concerned about providing clients with the best service possible.”

Hard work doesn’t bear as much fruit as it once did. Sometimes it seems like the economy would be better served if Japanese spent more time enjoying themselves and spending money and generating domestic demand rather than working.

Japanese Seeking Less Materialistic Lifestyles

Kenichiro Ito lived in the town of Hayama, Kanagawa Prefecture, and now travels around the Kyushu region, where he is originally from, in a two-ton camper. The 49-year-old closed his insurance agency business, canceled his apartment lease and disposed of all his furniture. Only cooking utensils, a sleeping bag and clothes were left. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 14, 2012]

The 2008 Lehman shock forced Ito to begin questioning his life. "Once money is gone, customers leave and I lose my job. I realized I'm living a very tenuous life," he said. And his doubts about such a life deepened after March 11. Having seen houses washed away by the tsunami and people supporting each other in temporary shelters, Ito thought he could also lose his home and job some day. He then asked himself what "assets" would be left to him.

In April, Ito found a used camper on the Internet and several days later bought it in Osaka for 2 million yen. Ito said he made up his mind to buy the camper after carefully thinking it over. "I wanted to see my friends in western Japan, and I let go of unnecessary things," he said. He gave his savings to his family.

Ito remodeled the camper to run on waste oil and made business cards that carry no job title and described him merely as a person on an odyssey. After making preparations, he began his journey in autumn. He essentially spent money only on food and obtained waste oil, such as used tempura oil, from people he met on his trip. He said he was reluctant in the beginning to rely on others, but one of his friends told him: "Some people are happy to help others. You could become a different person through this trip. It'll be good for you." Two months later, Ito returned to Hayama. By then, he had given out all 200 business cards he made before the trip.

Consumerism grew following the nation's rapid economic growth between the late 1950s and early 1970s. But many people are now rethinking lifestyles characterized by money and consumption, once considered symbols of happiness. This trend is reflected in the results of a survey on post-disaster consumer awareness. According to the survey conducted in December by Dentsu Inc., 78 percent of 1,200 respondents aged 20 to 70 said they want to rethink their priorities and make better use of their money and time.

Masahiro Yotsumoto, general manager of Dentsu's Human Insight division, said people's interest has shifted from materialism to a life not bound by possessions. "Since the quake, a growing trend has been to save money on everyday items, but spend big on things of interest," he said.

Personal Savings in Japan

Japanese bank The Japanese are among the world's best savers. The savings rate among Japanese is around 20 percent, compared to 5 percent in the U.S., 11 percent in Germany 13 percent in France, 12 percent in Britain, and 15 percent in Italy. In 2002, individual holdings in cash, investment and savings in Japan amounted the $11.4 trillion ($6.4 trillion in household savings), the world’s largest domestic savings.

The saving rates in Japan were 14 percent in 2006, 12 percent in 2005, 7 percent in 2001 and 14 percent in the 1990s.

Total household financial assets topped ¥1.5 quadrillion for the first time in December 2005 and reached ¥1.56 quadrillion in June 2007. In June 2011, Japanese households held a record ¥828.52 trillion in cash and deposits reflecting the tendency of people to seek sake assets when the economy is sluggish and after a serious problem like the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami in 2011

The Japanese have not always been big savers. Japan had low savings rates in the 19th century. Saving was encouraged beginning at that time in nationwide campaigns aimed at financing Japan’s industrial revolution. In the postwar years, savings were reinvested heavily in Japanese businesses. Recently, the Japanese have been accused of saving too much. It has been argued that if consumers spent more it would stimulate the economy.

One survey found that Japanese have 50 percent of their household financial assets in cash and savings, percent in bonds, 5 percent in trust fund and mutual funds, 11.3 percent in stock and capital investments, 26.4 percent on insurance and pension funds and 4.3 percent in other. By contrast, Americans have 13 percent of their household financial assets in cash and savings and 7 percent in bonds, 14.3 percent in trust fund and mutual funds, 31.2 percent in stock and capital investments, 31 percent in insurance and pension funds and 3.5 percent in other.

High savings rates are a good thing in country with with an aging populations because it shows that people are willing to defer growth for now in return for security in the future.

Closet Money and Hidden Savings in Japan

Many Japanese don’t even put their savings into banks. They keep it in boxes or stashed in drawers at home. By one estimate there is $700 billion in “closet money” out there. About two thirds of this cash is held by people 65 and older. When new banknotes were issued in 2004 and 2005 it was hoped the new notes would encourage people either to spend their “closet money” or at least put it in the bank. Many Japanese are afraid to put their money in the bank because of stories they see on the television news about bank card theft.

In January 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A record 84 trillion yen ($1.07 trillion) has been left undeposited at year-end, as people choose instead to keep cash at home or in office safes, according to the Bank of Japan. The amount is up 2 percent from the previous year's figure. It is the second straight year in which a record amount of cash was left undeposited. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, January 1, 2012]

“An increasing number of households are believed to be keeping cash at home instead of depositing it at financial institutions because of the ultra-low interest rate, while the Bank of Japan continues supplying a large amount of cash to the market in its monetary easing policy. Companies also are assumed to have a large amount of cash stashed in their office safes for emergency use, given the uncertain economic outlook.

Wives' 'Secret Savings' Rise as Bonuses Shrink

In July 2012, Jiji Press reported: “Japanese wives hold record amounts of so-called secret savings, while their husbands' bonuses this summer sank to record lows, a life insurer survey showed. The average after-tax summer bonus of husbands fell by ¥65,000 from a year before to ¥611,000, the lowest since the survey began in 2003, Sonpo Japan DIY Insurance Co. said. The amount of savings that wives have quietly salted away from their husbands' income averaged ¥3,843,000, up ¥477,000. The figure was the highest since 2005, when questions about such secret savings were added to the survey. [Source: Jiji, July 6, 2012]

“The survey, conducted online during the six days to June 13, covered 500 women aged between 20 and 60 whose husbands are salaried workers. More than 40 percent of the responding female homemakers said they have secret savings, according to the survey.

“Asked how their families plan to use summer bonuses, 72.8 percent of the respondents, the biggest proportion, said they will save them. The second-most popular use was for living expenses, cited by 38.2 percent. Loan repayments were mentioned by 32.6 percent. Multiple answers to the question were permitted.

Postal Savings in Japan

Japanese post office Nearly all Japanese have their savings in post office savings accounts. There are nearly $3.8 trillion invested in low interest postal savings account loans. Japan Post also hold ¥140 trillion of government bonds, making it the biggest owner of Japan’s national debt. If the Japanese postal system is regarded as a bank it would be the world's largest and some say the worst run.

Public corporations such as the postal services underwrote much of the economic activity in the 1990s but were very unprofitable. Large amounts of money from the system has been used by the government to fund pork barrel projects and finance bridges to nowhere.

The Japanese postal system also offered insurance policies. Unlike bank saving accounts and company insurance policies, post office savings accounts and insurance policies are protected by the government. The bank pays virtually no taxes and deposit-insurance premiums.

The postal system was regarded as a major obstacle to prosperity and economic growth because it sucked up household savings and wanted and used the money efficiently.

Credit Cards and Personal Debt in Japan

Number of credit cards per person: 2.3, compared to 4.2 in the United States. Credit card debt per person in Japan is 70 cents, compared to $2,607 in the United States . Debt as a percentage of disposable income: 0.003 percent, compared to 10.1 in the United States. The number of credit cards in Japan has increased 55.6 percent between 2002 and 2007. [2007, Sources: Eurominitor, Bloomberg, New York Times]

JCB is Japan’s largest credit card company. As of the mid 2000s it had 51.6 million cardholders, most of them Japanese, and operated in 189 countries. By contrast Visa has 1.08 billion cardholders.

Japanese owe $5,332 per person compared to $11,094 by Americans and $27,746 by Greeks.

Saving rates have dropped, and may people have accumulated huge debts. In 1999, roughly 1 in 8 Japanese found themselves in debt with high-interest loans. Some sought relief from loan sharks.

By one estimate 2.3 million Japanese are heavily on debt to more than five consumer loan companies and have serious repayments problems. In 1998, there were 130,000 “yonige” (people who flee into the night to escape debt), twice as many as the year before. Debt is blamed in large percentage of Japan’s 30,000 suicide. Many were men called the “can’t say no” type.

See Government, Crime...; Crime, Loan Sharks,

A study in 2005 found that the percentage of households with no savings hit 22.8 percent, the highest since surveys on this subject were kept in 1953.

Consumer Loans in Japan

Millions of Japanese have borrowed money from Japan’s 14,000 consumer loan companies and non-bank lenders. Some of them are deeply in debt and get further into debt when they borrow the money. The lenders offer cash, sometimes in minutes from ATM-like machines, without collateral.

Consumer lending is a ¥20 trillion business in Japan. It is dominated by specialized companies, sometimes called “salaryman’s finance companies,” that charge exorbitantly high rates and sometimes have connections with loan sharks and the yakuza. See Loan Sharks.

The lines between loan sharks and legal consumer finance companies is often blurry. Consumer loan companies that charge between 25 and 28 percent interest on their loans are among the most omnipresent advertisers on televison. Their ads feature cute Chihuahuas, smiling happy young women and dancing girls. There are 7,000 registers finance companies and thousands of unregistered ones.

In Tokyo there are machines operated by consumer loan companies that issue credit cards with a ¥2 million borrowing limited on the spot. The interest on loans using the cards was between 25.5 and 27.5 percent.

One collector for a consumer loan company told the Daily Yomiuri, “I belong to one of three teams, each of which is comprised 10 staff members. Our job was to relentlessly call people who had failed to make repayments for more than three months. He said his group made an effort to harass people when the were at work. The loan companies are not worried if a client commits suicide or buckles under the stress of repeated harassment. Many of the clients have insurance policies that promise to pay the loan company in the event the loan recipient dies.

In the mid 2000s Promise was the largest consumer lender in Japan followed by Aiful, Acom, and Takefuji. These companies advertise heavily on television and have offices near train station with signs like “This is the way out when you’re in trouble.” Until recently many of them charged the maximum legal rate of 29.2 percent.

In Tokyo in the early 2000s, a small business owner took four bank employees hostage, saying that their boss had ruined his life by charging outrageously high interest rates.

Crackdown on Consumer Loans in Japan

In January 2006, the Supreme Court of Japan ruled that standard loan contracts — which often require the borrower to repay in full immediately if they miss one payment — was illegally coercive. The ruling invalidated the borrowers’ agreement, exposing lenders to claims for billions of yen in refunds. In December 2006, new laws were passed that capped the interest rates the loan companies were allowed to charge 20 percent, down from the previous 29.2 percent..

Loan companies were hurt bad by the decisions. Their stocks plummeted and they were forced lay off workers and close branches. Hundreds of non bank lenders went out of business. The decisions were considered a boost for loan sharks who are not strapped by laws and rules as legal businesses.

The high “gray zone” interest rates charged by consumer loan companies are suppose to be abolished in 2010.

The consumer lending business was hit hard by the rulings against charging excessively high interest rates and claims by individuals seeking reimbursement for excessive interest rates. In September 2010, Takefuji, once a leader of the industry, filed for bankruptcy.

In September 2010, the Incubator Bank of Japan, a lender specializing in loans to small and medium-size business, filed for bankruptcy, The limited deposit protection system — which insures deposits up to ¥10 million — was invoked for the first time. Those with deposits below ¥10 million were happy that the protection system was in place. Those with deposits above ¥10 million were concerned about losing a big chunk of their life savings.

Image Sources: 1) 3) 4) 5) 8) Ray Kinnane, 2) 10) Goods from Japan, 6) Japan Visitor, 7) Doug Mann Photomann, 9) Danny Choo

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2012