EVERYDAY LIFE IN JAPAN

hanging the futons,

a weekly chore in Japan Many Japanese customs, values and personality traits arise from the fact that Japanese live so close together in such a crowded place. Everyday the Japanese are packed together like sardines on subways and in kitchen-size yakitori bars and sushi restaurants. A dozen lap swimmers may squeeze into single lane at a swimming pool. Bicycles and pedestrians fight for space on crowded sidewalks, which are especially packed on rainy days and sunny days, when umbrellas are out in force. If there weren't such strict rules and strong pressures to obey them people would be all over each other, in each other’s face, and at each other's throats.

Businessmen spend the night in coffin-sized sleeping capsules. People entertain outside their homes because there is no room to entertain guests inside their homes. Lawns are so small they are cut with scissors and gardens are so small Japanese say they will fit on a "cat's forehead." The shortage of space has been the inspiration behind Japanese engineering wonders such as the Walkman, candy-bar size cell phones, compact cars and wafer-thin television sets.

Common Japanese tools include a nata, a wonderfully functional Japanese tool--sort of like a cross between a long-bladed hatchet and a heavy fish cleaver, and a kama--a short, single-hand sickle, for cutting heavy brush, and a short-handled bamboo rake. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri]

With personal space being so hard to find in Japan the concept of privacy is more of state of mind than a condition of being alone. The Japanese are very good at shutting out the world around them and making their own privacy by losing themselves in reading a comic book or sleeping while they are surrounded by people. But even that is not enough for some people. All over Japan, you see men parked in their cars sleeping or reading, sometimes for hours at a time.

Every person in Japan belongs to a family registry that documents marriage, births and deaths. The registry system was introduced in the Meiji period in the 19th century as means of keeping track of its population. The government also keeps track of people through tax, pension and health care records. The government issues identity cards and requires anyone who moves to record the move with local authorities. Some say the bests way to make sure you get along with your neighbors are quickly passing along the kairanban clipboard of local announcements and observing the garbage disposal regulations properly.

Japan was rated No. 11 in the United Nation Quality of Life Index in 2010. Norway, Australia, New Zealand and the United States were the top four rated countries.

Good Websites and Sources: Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de , japan-photo.de , japan-photo.de ; and japan-photo.de ; A Day in the Life of a Japanese Kid cusd.chico.k12.ca.us ; Google-E-Book: Japan “ Why It Works, and Why It Doesn’t: Economics in Everyday Life books.google.com/books ; Everyday Scenes jun-gifts.com ; Fixed in Life Blog, with Lots of Photos jeromesadou.com ; Photos funzu.com ; Statistical Handbook of Japan Family Budgets and Prices stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook ; 2010 Edition stat.go.jp/english/data/nenkan ; News stat.go.jp Links in this Website: URBAN AND RURAL LIFE IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Sites for Expats Japanable site for Expats japanable.com ; That’s Japan thats-japan.com ; Orient Expat Japan orientexpat.com/japan-expat ; Kimi Information Center kimiwillbe.com ; Foreign & Commonwealth Office Report on Japan fco.gov.uk/en/travel-and-living-abroad ; Student Guide to Japan www2.jasso.go.jp/study ; Japan in Your Palm japaninyourpalm.com

Things to Love About Life in Japan

On things to love about life in Japan, Andrew Bender wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “1) Vending machines. Sure, we have vending machines in the States, but machines that sell hot and cold canned drinks, with temperatures that can be changed seasonally. All kinds of awesome. Vending machines are a way of life in Japan, selling subway tickets, Coke on a mountainside by a middle-of-nowhere hiking trail, beer, toys, even underwear. [Source: Andrew Bender, Los Angeles Times, March 11, 2012]

2) Tatami rooms. Minimalism may have been discovered by the rest of the world over the last 50 years, but it goes back ages in Japan. A traditional Japanese room has tatami (mats) on the floor, simple stucco walls supported by wooden posts, and an alcove called a tokonoma, used to display your changing selection of hanging scrolls, pottery and seasonal ikebana. 3) High-tech toilets. Are heated toilet seats necessary? Maybe not, but they sure are nice on a cold winter morning. Japan has elevated plumbing to an art, and the graphics on the push buttons are adorable.

4) 100 yen stores. Japan is famously expensive, but more and more (not just) Japanese are shopping at the equivalent of dollar stores. You're not going to get top-shelf stuff, but the wares “ rice bowls to rice crackers, neckties to knickers “ are often equal to what you'd buy elsewhere. Where else can you outfit your entire kitchen for the equivalent of $50?

5) Taxis. Sorry, America. Japan has us beat on this, white-gloved hands down. Taxi doors open and close automatically, lace doilies cover the seats, drivers are unfailingly polite and tipping never enters their mind. If you don't know the route or can't speak Japanese, it's a good idea to have a map to your destination. In the unlikely event that the driver takes the wrong route, I've had instances where he (or, increasingly, she) will shut off the meter.

6) Tokyo subways. Other cities only wish they had a Metro. Tokyo's amazing train network is the envy of the world, spotless, punctual and genteel. With 13 lines below ground and a tangle of additional lines above ground, it's the life blood of the city. If you hear anyone talking loudly on board, it's almost certainly not in Japanese. Those images you've seen of packers shoving folks into cars “ only at certain stations during rush hour.

Economic Daily Life in Japan

Japan is very cash oriented. Coins and banknotes account for 15 percent of national income compared to 6 percent in Germany and 3.5 percent in the United States. Credit cards are not as common in Japan as they are in United States. Japanese walk around with large amounts of cash and pay for most things with cash. Before making a large purchase, they are more likely to run to an ATM machine than use a credit card. ATM machines dispense up to $30,000 in yen.

Japanese housewives have traditionally controlled the family's finances. They are careful shoppers and like things fresh. They look out for bargains like everyone else but don’t go in for buying things in large quantities like Americans, partly because they don’t have room in their relatively small houses for a lot of stuff. Women are also some of Japan's most active investors.

There are almost no checking accounts or paychecks in Japan. Most people get paid though bank transfers to their bank savings accounts and pay bills by making money transfers at a bank, post office or convenience store that cost as much as $5 each. Instead of waiting in line at a bank, most people give their money or papers to receptionist and then sit and relax on a couch until the transaction is finished and are called to a window.

Consumer Habits in Japan

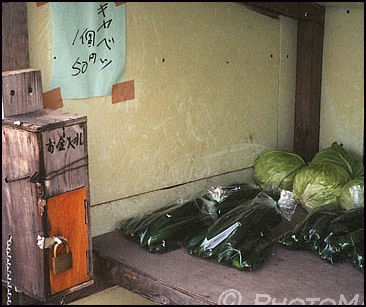

an honor-system vegetable stand

where customers take what

they want and leave money Japanese consumers are notoriously fickle and demanding. They often chose quality over price. Expectations for quality and freshness are high.

Japanese are willing to pay more for quality. Nice supermarkets that have good quality stuff often do better than ones with everyday low price places. Ken Belson wrote in the New York Times: “Japanese consumers are considered the world’s most discriminating, particularly those who have traveled overseas. Product cycles are short; preferences swing wildly, especially among younger women; and Japanese consumers tend to be fanatical when it comes to quality.”

Japanese prefer smaller, lighter products and are willing to pay high prices for them. They are also willing to spend money for the latest and coolest stuff. By contrast Americans often seem interested most in the lowest price. One young Japanese woman told the New York Times, “It’s much better to buy one good thing and use it carefully than spend money on many cheap things. As I become busier, I don’t have as much time to shop, so I only go to places where I can get good things.”

Daily Chores in Japan

Rice is usually prepared in a special steam rice cooker that has a special timing device so rice can be prepared for the next morning while people are sleeping. Japanese housewives usually shop every day on foot; iron on small foot-high ironing board that fits on the floor or table; and sometimes serve food on heated “kotats” tables in the winter.

Most homes don't have an oven or dish washer. Refrigerators and washers are generally smaller than their American counterparts. Cooking is done on a stove-like cooker.

Most homes don't have a dryer or even a hair dryer because the Japanese believe the Shinto Sun goddess Amaterasu looks down are thing that are not dried in the sun. Clothes are hung in the morning on the balcony. If it is raining clothes are hung indoors from doorknobs and lines strung on ceiling hooks.

Shoes, Slippers and Dogs in Japan

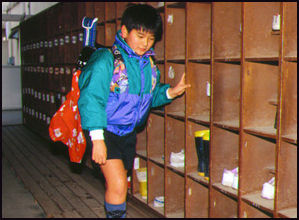

school shoe boxes According to Japanese custom, people are supposed to take off their shoes when entering a house. The shoes are taken off at the “genkan” (threshold, or entrance area) inside the house and one has be careful not to step on the genkan with their barefeet or socks (Japanese step out of the heels of both shoes first and then step into house without stepping on the threshold). The custom was developed to keep the floors in the house and especially hard-to-wash tatami mats clean.

Often Japanese step into slippers for walking around in the house but remove their slippers when entering a tatami-mat room. If you go the bathroom you put on a pair of plastic slippers in the bathroom and then change back into the original slipper when you step out of the bathroom.

It takes some skill to take off and especially put on your shoes at the door with grace and ease. It is a bad idea to wear hiking boots are shoes that require lacing up or are difficult to step in and out of. The custom of removing shoes was developed when people most wore sandals. Shoe horns are often available. If you need to sit to put on or remove your shoes apologize.

In Japan, there are too kinds of dogs: small dogs that are allowed in the house and outdoor dogs that have to stay outside and are not allowed inside because of worries that they will dirty the floor or the tatami mats with their feet.

Sleeping and Sitting on the Floor in Japan

A lot of Japanese sleep on the subways and trains. At home they often sleep on futons (but many also sleep on beds). In the summer they sleep under towels. After waking up a futon sleeper is expected to fold up his or her futon and blankets and place them in a closet or against a wall.

The Japanese spend a lot of time sitting on the floor, and if given the choice some would rather sit or lie down on a hard floor than relax on a bed or in a comfortable chair. When sitting on the floor many people sit on cushions.

The preference for sitting on the floor goes hand in hand with not wearing shoes in the house. Japanese don't want to sit on a floor dirtied by people's shoes. If you sit in a chair it doesn't make as much difference if the floor has a little dirt.

The “seiza” style of sitting on your knees — with the legs bent and tucked under the bottom — is regarded as polite. The more relaxed “agura” style is referred to as “Indian style” in the United States. Woman sitting the seiza position that perform a proper bow do so with their hands on top of each other and the elbows out.

Women are not supposed to sit cross-legged on the floor. They are supposed to sit with their legs bent under them or bent to the side (both positions are generally very uncomfortable for Western women for long periods of time).

Eating Habits in Japan

A traditional meal is served with rice, vegetables and miso (fermented soy bean paste) soup and fruit is often eaten as desert. Many dishes come with soy sauce or wasabi (very hot mustard-like green horseradish). Many urban Japanese have adopted the American way of eating — a big breakfast, light lunch, and a big dinner. Miso soup and rice are a dietary base, often eaten for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Breakfast (asa-gohan) is generally eaten between 7:00am and 7:30am and consists of juice, coffee, eggs and toast or rice. A typical breakfast consists of rice, miso soup, spinach and egg. Most people eat breakfast at home. It's hard to find a restaurant that serves breakfast. Many coffee ships have a set breakfast with a drink, toast, boiled egg and light food. On the weekends people eat pancakes or a traditional breakfast of miso soup, rice, egg, vegetable and fish.

Lunch (hiru-gohan) is generally eaten between 12:00 noon and 2:00pm. Many people eat out, grabbing a quick meal or snack such as a bowl of noodles, sandwiches, rice balls or Chinese food.

Dinner (ban-gohan) is generally eaten between 6:00pm and 8:00pm. It generally an informal meal with meat or fish, rice and miso soup. Main dishes made at home, include thing things like curry rice, pork cutlets, meatloaf-like hamburgers, fried fish, stir fried chicken or pork dishes, and dishes made with tofu. Fancier dinners include some of the items listed below.

Japanese often drink nothing with their meals, Miso soup often serves the purpose of a drink. Sometimes beer, wine, hot tea, cold tea, water or other drinks are served with their meals. An evening snack of fruit is commonly eaten around 10:00pm.

School Life in Japan

The school day lasts from around 8:00am to 3:00pm but varies from day to day. Although it is a little longer than in the U.S. school day, Japanese students generally have more free time and breaks during their time at school. Sports clubs, even ones for elementary school, sometimes require students to show up for practice early in the morning or stay at school until 6:30 or 7:00pm.

“Souji” ("honorable cleaning") is a period of about 15 minutes each day when all activities come to a stop, mops and buckets appears and everyone pitches in cleaning up. Often the teachers and principals get on their hands and knees and join students.

Japanese schools don't have any janitors because the students and staff do all the cleaning. Students in elementary school, middle school, and high school sweep the hall floors after lunch and before they go home at the end of the day. They also clean the windows, scrub the toilets and empty the trash cans under the supervision of student leaders. During lunchtime, sometimes donning hairnets, students help serve the meals and clear away dishes.

All primary school kids eat school lunches, and about 8 percent of middle school students do. Japanese students eat their lunches in the classrooms (there are no cafeterias in Japanese schools) and help prepare and serve school lunches. Food is served from stainless serving trays and large pots by students, who sometimes wear surgical masks, aprons and hair protection. The food is often prepared in a kitchen on one floor and transported to the classroom on special carts using special elevators.

Classrooms are not heated or air conditioned. In the winter students show up in their winter coats, scarves and gloves. Sometimes their ears and noses turn red and they can see their breath. In July, they endure sweltering classrooms without even fans.

Children in Japan learn preparedness at an early age. In kindergarten they are taught to fold their jackets properly and always have tissue in one pocket and a handkerchief in the other. In grade school they learn to have three sharpened pencils in their desk — not four, not two — and always have glue, rulers and erasers close at hand in their pencil boxes. Elementary school students change into slippers when they arrive at school and put their shoes on special shelves. They all carry the same kind of correct backpack and are informed of the one correct way to adjust its straps.

Little Free Time for Children in Japan

Elementary school students have plenty of time to play around with their friends after school if they are not too busy with after-school activities. A typical middle school or high school students, however, arrives home from school at around 4:00pm, has a quick snack and attends cram school classes, often three times a week from 5:00pm to 10:00pm. Sometimes students have cram school classes Saturday and all day Sunday too.

Elementary school kids are usually very busy with activities two or three days a week after school Girl usually take ballet, dance or piano. Boys play baseball or do karate. Both boys and girls take English, calligraphy, arithmetic or swimming lessons.

One of the biggest tragedies of the Japanese education system is the fact that children and teenagers study all the time and they have little time left over for fun or developing social skills. Students at one Japanese high school were beside themselves with envy when a visiting American high school student talked about how he spent his after school hours driving a car to the mall, dating, making money with a part-time job and talking on the phone for hours in the evening.

A typical Japanese student takes a break after school and then runs off to juku classes. Later he or she often does homework. One Japanese student told U.S. News and World report, "I can play an hour with my friends before cram school."

Housewife Duties in Japan

Japanese housewives have been described as "overscheduled, sleep-deprived and permanently exhausted." They often get up a half hour before everyone else to prepare rice for the morning breakfast, run around all day doing various things to take of the needs of their children, husband and often one of two aging parents, and after checking to make sure their children's homework is done are the last ones to go to bed at night.

The daily activities of a highly-organized Japanese mother include taking care of the family finances, meticulously cooking every meal, keeping the house clean and orderly, attending P.T.A meeting and music lessons, handling important household purchases, making most of the schooling decisions, giving out allowances to their husbands, properly washing the clothes and folding the futons and placing them in the closet.

Some Japanese women dress their husbands in the morning and serve them the choices cuts of meat and special delicacies at dinner. Some even rush onto a train to grab a seat for their husband and then stand up, arms filled with shopping bags, while the husband relaxes and reads a pornographic comic book. [Source: Deborah Fallows, National Geographic, April 1990]

One elderly woman told the New York Times, “I worked hard to raise our children and to help my husband’s business too, but nothing I did was appreciated. For most of my marriage I wasn’t allowed to decide anything, not even what to put in the miso soup. For that I had to defer to my mother-in-law.”

Park Mothers and School Lunches in Japan

fancy bento lunch Because most homes don't have yards and babysitters are a rarity, many Japanese mothers spend their days in their local park with their children. The practice is so common that books, newspapers and television dramas often have references to these "park moms." [Source: Marry Jordan, Washington Post]

Park society has a rigid hierarchal social structure that is reflected in Japanese society as a whole. Every woman has a rank and leaders decide who can be admitted to certain cliques and what activities and fashion are acceptable. A park mom expert told the Washington Post, "May Japanese women have the anxiety of having no identity. For them, the park group, however small, is the start of a place to belong."

In a book on park mom etiquette, “Park Debut”, newcomers to the park scene are advised "take a low posture," "be cautious to an unknown face," and "imitate the elder bosses."

Mothers are often judged by how well they prepare their child's “o'bento”, an "honorable lunchbox" which usually contains fresh peas, boiled eggs, lotus roots, mint leaves, tomatoes, carrots, fruit salad, minced chicken, seaweed is cut into teddy bear shapes and fluffy white rice with a plumb in the middle (symbolizing the rising sun on the Japanese flag).

A sloppy lunch box is regarded as a sign of an uncaring mother. Making bentos has been described as means for mothers “to demonstrate their devotion to motherhood, dedication to heir children’s nutrition and creative skills. One mother told AP, “This is about my pride.”

Community Obligations in Japan

Many Japanese urban neighborhoods have a sense of community with a set of mutual rights and obligations that is not unlike that of a rural village. On Sundays, for example, you can see groups of older Japanese men wearing the same hats and jackets cleaning up litter around their apartments. In some places parents are fined if they don't show up at P.T.A. meetings.

“Kairanban” describes a system in which one neighbor delivers a clipboard with various announcements regarding the community and the recipient of the clipboard is expected to pass it on to another neighbor. Each exchange is accompanied by a nice chat and exchange of gossip. A similar system called “renrakumo” is issued to pass on messages from the school to one groups of parents and then another.

In the old days rural communities worked together to build bridges, maintain shrines and temples and participated in fire-fighting brigades.

Mailboxes are typically filled with advertisement for English lessons, pizza parlors and neighborhood brothels. Door-to-door visitors include condom salesgirls, Buddhist political party canvassers and toilet paper exchangers that exchange rolls of toilet paper for magazines and newspapers.

Hankos (Signature Chops)

Instead of signing their name, Japanese stamp their name on forms, bank withdrawal slips and letters with a “hanko” (chop, or signature stamp). Without a hanko one can't open a bank account in Japan or register for a university class. One professor told the Los Angeles Times, "I don't exist in this society without my hanko." [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, November 28, 2001]

Hankos are cylinders about the size of a piece of chalk. They have the person’s name carved at one end in Chinese characters and they leave an imprint after being stamped in ink. Everyone from the Emperor to a homeless man living in a park has a hanko, and they are used for everything from finalizing a multi-million-dollar business deal to signing for packages delivered to one’s house.

The average Japanese has five hankos but only one is registered with the government to certify ownership and it is only used on important documents. Since these seals are considered too valuable to carry around, people have other seals to use for things like bank transactions and taking deliveries. Many government documents have several hanko stamps. According one estimate a typical bureaucrats puts his hanko on 100,000 documents in a 25 year career.

Hankos have a 5,000 year history. Signature seals, which operates according the same concept, were used in ancient Mesopotamia and China. Japan's oldest example of writing is a solid-gold hanko dated to A.D. 57.

In the 8th century, only the Emperor was allowed to use a hanko. Later members of the Imperial court and noblemen started using them. The samurai class gained access to them in the Middle Ages. Ordinary Japanese didn't start using them until the Meiji period in the mid-19th century.

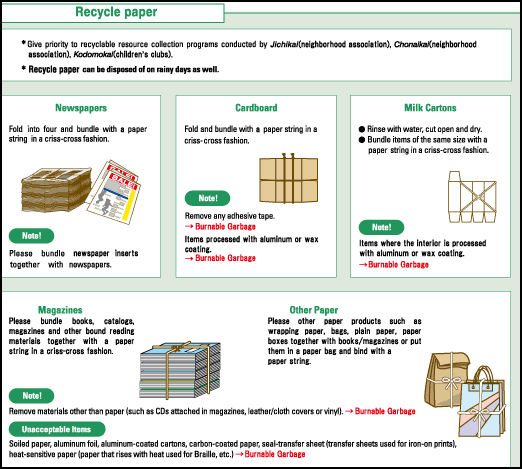

Yokohama English recycling instructions

Recycling in Japan

Japan is one of the world's most efficient recycling nations. The Japanese reuse over 50 percent of all household products, including 98 percent of their paper and 96 percent of their glass. To achieve this Japanese citizens are very good about followed rules set up my municipal governments outlined on a color-coded calendars that most people keep in their kitchens.

Households in most places sort items in eight categories and place them outside for collection on the days specified on the calendar such as 2nd and 4th Fridays for newspapers, glass and cans and the 1st Friday for discarded furniture and other large items. Large items such as bicycles or televisions can be collected by paying a fee to local government pick up services or giving them to people that cruise in small trucks, using a loudspeaker to tick off the items they collect.

In most places cans, bottles and newspapers are each placed in separate containers and picked up twice a month. Newspapers are also picked up by independent trash collectors who drive around in trucks and sometimes trade stacks of old newspaper for toilet paper. There are special collection days once a month for things like batteries, ceramics, old clothes, furniture, light bulbs, bicycles, televisions and other items. Supermarkets have receptacles for recycling milk cartons, plastic bottles, and Styrofoam trays.

In many places, trash has to be separated into burnable and nonburnable items. People that don't abide the rules have to deal with "trash lady," a local busy body who makes sure everyone toes the line. In some places, Japanese deposit their household trash and garbage in clear plastic bags with a tag with their name on it. The purpose of this is to humiliate people who place recyclable cans, bottles or newspapers in clear bag, which everyone who passes by can see.

Cell Phones in Japan

Cell phones in Japan can be used to look up bus and train schedules, reserve tickets, shop for apartments to rent, conduct personal banking, buy and cell stock, send graphics, check the latest Sumo results, down load horoscopes, pornography and jokes of the day, check pop music charts and see what is on at local theaters, museums and concert halls.

Females between 10 and 19 spend an average of 99 minutes a day accessing the Internet with their cell phones. The national average for that is 18 minutes.

Japan leads the world in multi-function cell phones, where handsets are available that double as televisions, remotes or subway passes, and can be used to buy sodas and beer from vending machines or conduct banking. NTT Docomo and Mizuho have worked out a system to make cash transfers from one bank account to another by cell phone.

Japanese seemed to be more fond of sending e-mails, messages and playing games than talking on their cell phones. On subways it often seems like every hand has a phone flipped open. Teenagers listen to music, read manga, and surf the Internet. Girls stop in restrooms to send progress reports about dates to their friends. Poets and musicians write down thoughts that pop into their minds. Young kids are e-mailed their parents, asking them where they are.

Messages are sent with fast flaying thumbs. Some Japanese spent so much time entering messages with their thumbs they have started using their thumbs to point at things and ring doorbells. Young people who grew up playing video games and matured using cell phone developed thumbs that are stronger and more muscular that those of older people. Some can peck out 100 Chinese characters (the equivalent of 100 words) a minute with just their thumbs.

Bicycles in Japan

bike parking lot Bicycles are widely used as an alternative to cars. Commuters use them to ride to the train station. Trains stations are generally no further than 1½ miles part and the time spent on a bicycle is generally less than 15 minutes, with the bicycle being faster and more convenient than buses or walking. Most train stations have large bicycle parking lots.

Mother use bicycles to go shopping, take their kids to day care and run errands. They often ride their bicycles around with their young children in special seats in the back and at the front of their bicycles, sometimes with primary-school-age kids tagging along on their own bikes.

Young women in high heels, men in black suits and teenagers on cell phones all ride bikes. Hardly anyone wears bicycle helmets but many people ride in the rain with special clamps on their bikes for their umbrellas. If they don’t have the clamps they ride holding an umbrella in one hand.

The parking of bicycles outside designated areas, especially around train stations and shopping areas, is a big problem in some cities. Special parking garages for bicycles have been built but bicyclist find them expensive and inconvenient and they are sometimes filled to capacity.

Bicycle parking lots with a capacity of 2.4 million bicycles have been built near trains and subway stations throughout Japan. Some look like parking lots for cars and are massive but even then there are not enough spaces. Bicycles that are left outside designated parking areas are sometimes given tickets or are even impounded by police.

Trains and Subways in Japan

Japanese spend a lot of time on subways and trains. Rush-hour trains and subways in Japan can be quite crowded. One commuter told the Daily Yomiuri, "Every morning, I pack myself into an overcrowded train, so by the time I arrive at work, I'm already exhausted.

The trains are so packed that people routinely faint. "On a bad day, we could have three o four people falling sick," a train employee told the New York Times. "Many of them are women who are skinny, who skip their breakfast or are on a diet, and they're not able to cope with rough crowds in the train."

Passengers line up at special marks o the platform to reduce the time that a train spends at each station to as little as 30 seconds. Those waiting to get on patiently wait for those get off before boarding. On the train many passengers read, dawdle with their cell phones or sleep. Some commuters favor positions which allows them to read or sleep. During the winter when people are bundled up in winter coats, they have more padding to absorb the pushing and shoving but less people can be squeezed into a train car.

The JR Saikyo Line is known as one f the most crowed rush hour train in Tokyo. Describing a ride Chie Matsumoto wrote in the Asahi Shimbun: “Hell is probably not as crowded as a commuter train in Tokyo...I was shoved through...the carriage. I was smashed. I was stepped on and squeezed. At last I was devoured....If someone stepped on my foot that meant I had my feet on the floor; I was smacked about I had some room to breathe....I tried not to think about the person breathing hotly — in and out, in and out — on the back of my head.”

Station attendants with white gloves still shove passengers into subways cars on crowded subway lines — as Life magazine showed them doing in the 1960s. The cars often hold more than twice the capacity they have been built for. The most crowded train in Japan is the stretch between Ueno and Okackimachi stations on the JR Keohin Tohuku Line.

Subway and Train Etiquette in Japan

Passengers on subways are expected not to sprawl across their seats, put their feet on the seats, eat or drink on the train (although a lot of people do this), put on their make up, talk on their cell phones or even listen to music on their I-pods. There are even posters that make the point.

There are special seats reserved for elderly people, pregnant women, injured people and women with young children. It is okay for other people to sit on these sas but if someone form he aforementioned groups shows they are expected to give up their sets t them.

In Yokohama teams of “courtesy staff” are employed on trains to encourage passengers to give up their seats for elderly or disabled passengers. Each team is accompanied by a security guard to ensure there is no trouble.

Long Commutes in Japan

The average salaryman, who Ozawa described as "commuter slave of commuter hell," spends an average of three and half years commuting to and from work on trains where there isn't even enough space to read. One magazine wrote an article about a salaryman with single worst commute to Tokyo — three and half hours each way.

"Despite the indignity and physical agony, commuters suffer in silence," one newspaper wrote. "there's no room to read a paper or magazine," one commute lamented. "I carry a radio sometimes and listen to the news or music. I'm alone. I don't know anyone on the train. Everyone is like that."

Photographer Peter Menzel lived for a week with a salary man who "wakes up at the last possible second...and walks out the door a 7:28 sharp. he times himself with a little clock on the TV screen. Then he walks to the station, arriving 45 seconds before the train (which is exactly on time, this being Japan).

Employees get commuting expenses. Salarymen who can't make the train often stay at a company dormitory in Tokyo. In there was a trend for people to move into highrises in the city rather than homes in the suburbs. One reason for this is that many people were tired of long commutes.

Service in Japan

Japanese like service and have traditionally been willing to pay for it. Department stores and health clubs have a lots of extra employees that do little more than say hello and goodby to customers and address their often trivial requests. At service stations employees not only pump the gas and clean the windshield and check the oil, they also empty ashtrays, clean the tires, check the transmission fluid and battery, and shout a hardy "”Irashaimase”!" ("Welcome!") when drivers arrive and stop traffic and direct them out when they leave. When oil companies tried to introduce the idea of self-service stations, Japanese customers didn’t go for it.

Service in company and government offices is very good. Generally any person in a department can help you even if you are there at lunch time. The service in shops and department stores in generally also very good Unlike the United States, where you often have to search around for somebody to help, and then they either lack knowledge or have an attitude, in Japan there is usually a lot of eager, friendly and helpful sales staff on hand.

Kimoko Manes, author “Culture Shock of Mind”, sees that American and Japanese attitudes about service related to differences between American individualism and Japanese group mentality in that in the United States individuals tend to worry about their individual concerns and their responsibilities while those of their co-workers are their problem while Japanese tend see themselves as members of group and each individual in the group is capable and responsible for the demands made on that group.

Savings in Japan

The Japanese are among the world's best savers. The savings rate among Japanese is around 20 percent, compared to 5 percent in the U.S., 11 percent in Germany 13 percent in France, 12 percent in Britain, and 15 percent in Italy. Total household financial assets topped ¥1.5 quadrillion for the first time in December 2005 and reached ¥1.56 quadrillion in June 2007.

The Japanese have not always been big savers. Japan had low savings rates in the 19th century. Saving was encouraged in nationwide campaigns aimed at financing Japan’s industrial revolution. In the postwar years, savings were reinvested heavily in Japanese businesses. Recently, the Japanese have been accused of saving too much. It has been argued that if consumers spent more it would stimulate the economy and help the country avoid recessions.

Many Japanese don’t even put their savings into banks. They keep it in boxes or stashed in drawers at home. By one estimate there is $700 billion in “closet money” out there. About two thirds of this cash is held by people 65 and older. When new banknotes were issued in 2004 and 2005 it was hoped the new notes would encourage these people either to spend this money or at least put it in the bank. Many Japanese are afraid to put their money in the bank because of stories they see on the news about bank card theft.

One survey found that Japanese have 50 percent of their household financial assets in cash and savings and 3 percent in bonds, 5 percent in trust fund and mutual funds, 11.3 percent in stock and capital investments, 26.4 percent on insurance and pension funds and 4.3 percent in other. By contrast, Americans have 13 percent of their household financial assets in cash and savings and 7 percent in bonds, 14.3 percent in trust fund and mutual funds, 31.2 percent in stock and capital investments, 31 percent on insurance and pension funds and 3.5 percent in other.

Vending Machines in Japan

cell phone vending machine Vending machines are everywhere in Japan. Not only can you buy candy, juice, cigarettes and soda pop you can also buy hot coffee in cans, cold beer, rice, milk, bottles of scotch, batteries, compact discs, software, panty hose, videocassette, magazines, and pornography. Some offer manicures. Others sell stag beetles, used panties and pearls ranging in price from $39 to $235. According to one estimate there are more than 5 million vending machines or about one for every 30 Japanese. Perhaps one reason they are so many is due to the low crime rate and lack of concern about break ins.

According to the Japan Vending machine Manufacturers Association there are 5.5 million vending machines in , including those that sell ticket, in Japan, making it the second largest vending machine country after the United States. There works out to about 1 vending machine fore every 20 people. About 2,6 million of them sell soft drinks.

There are vending machines at museums that dispense miniature art works. New vending machines offer fresh sushi; warn buyers if certain good haven’t been properly warmed up yet; dispense drinks in cups provided by the user; talk to customers; offer drinks free of charge after earthquakes; scan customers with a camera and tell them what make-up they need; and tel customers the Japanese equivalent of “Have a nice day? or “sorry, I have run out of change? in the Osaka dialect.

Bureaucracy and Everyday Life in Japan

Residency permits are needed to live in any city. Whenever an individual or household moves they must report the move to local authorities at the city hall for their area and get a report which they take to the city they are moving to. Often a family is required to submit a “family registry” which list births, divorces, deaths and domiciles for their extended family.

Japanese citizens were outraged by an attempt by the government to give every individual an 11 digit number and put their registry permit information on a computer database in an effort to streamline the registry process. Local governments defied orders by the national government to comply with the effort and protestors decorated with bar codes drawn on their face took to the streets. Citizens were worried most about confidentiality issues, namely what would happen if the information got into the wrong hands.

Beginning in 2004, drivers licenses in Japan were imbedded with “smart chips” that will carries identity information and private information that was previously printed on the license.

Family Registy Back-Up

Family registers are official documents containing the personal information of individuals, such as their dates of birth and death and family relations. People register such information at municipal government offices, and the governments keep the data independently.

In September 2011, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “The Justice Ministry plans to launch a national network system to store backup data of family registers following the loss of data kept at four municipalities in Iwate and Miyagi prefectures due to the March 11 tsunami, it has been learned.” [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, September 29, 2011]

As of 2011, there was no computer network linking municipal governments with the Justice Ministry and its regional legal affairs bureaus. The municipalities make copies of family registers on tape, and send the tapes to the regional legal affairs bureau in charge of their areas.

The governments of Minami-Sanrikucho and Onagawacho in Miyagi Prefecture, and Rikuzen-Takata and Otsuchicho in Iwate Prefecture lost family register data after the March 11 tsunami destroyed their government buildings. The Sendai Regional Legal Affairs Bureau's branch office in Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture, kept copies of Minami-Sanrikucho's family registers, but the branch office was also submerged under the tsunami. Local residents worried that their town's family registers may have been lost completely.

Fortunately, the branch office's magnetic tapes were safe. However, as the Minami-Sanrikucho municipal government only sends tapes at the end of the fiscal year, almost all of Minami-Sanrikucho's family register data from fiscal 2010 was lost. The branch office tried to restore the lost family register data from information recorded on paper documents and kept at the branch office. However, it was impossible for the branch office to completely restore the family register data, and the loss of data delayed inheritances, marriages and other procedures.

Oldest Koseki Record Unearthed in Fukuoka

In June 2012, the Yomiuri Shimbun reported: “A wooden strip believed to be the nation's oldest koseki, or family registration document, has been unearthed at the Kokubumatsumoto site in Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture, the municipal board of education announced. The strip, believed to have been made late in the seventh century, during the Asuka period (592-710), is older than Japan's currently recognized oldest existing koseki, an artifact from the year 702 that is kept in Nara's Shoso-in repository. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, June 14, 2012]

“Its discovery also highlights the likelihood that the central government already directly controlled people over wide areas before the Taiho Ritsuryo--the first nationwide law, equivalent the present-day criminal code and administrative and civil laws--was established in 701. Many historians have believed centralized government came fully into being with the law's enforcement.

“The 0.8-centimeter-thick wooden strip is 31 centimeters long and 8.2 centimeters wide. It bears the character "kori," a word for a local administrative unit used before the enforcement of the nationwide law, equivalent to a present-day "gun," or county. The strip also bears "shindaini," a title established in 685, leading researchers to conclude it was made at the end of the seventh century. Some of the text on the strip reads, "The head of the household is Takerube no Mimaro," and, "His younger sister is Yaome." The names and relationships of 16 members of the same community are described. The strip also bears the terms "seitei," or healthy men aged 21 to 60, and "heishi," meaning soldiers conscripted from among the seitei. According to the researchers, the strip also includes words to describe dividing a household in two and the head of the household before the division.

“From these findings, the researchers believe the information on the wooden strip was an update for the Koinnenjaku, the nationwide family registration system compiled following the 689 establishment of the Asukakiyomihararyo, the legal code in effect prior to the Taiho Ritsuryo law. Kogonenjaku, the family registration system introduced in 670, is believed to be the first such system compiled nationwide, while Koinnenjaku is believed to have been completed by 690. Until the strip's discovery, none of the original Koinnenjaku records were believed to exist, making the new discovery all the more significant.

“Some place names, such as "Shimanokori" and " Kawaberi," also are written on the wooden strip. Shimanokori is located in the northern Itoshima Peninsula in Itoshima in the prefecture. The researchers believe it is the same area as the place written in the oldest family registration record in the Shoso-in repository. The archaeological site is 1.2 kilometers northwest of the ruins of the Dazaifu regional administrative office, which oversaw the ancient Kyushu region, and about 30 kilometers from Itoshima. The wooden strip was unearthed from strata in a former riverbed during an excavation conducted prior to the construction of a condominium building on the site.

“Kazumasa Ikeda wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “Japan's early centralized government placed the highest importance on compiling a family registration system. By doing so, the government, supplanting powerful local clans, could gain direct control of the people, collect tax from them and impose laborious work and military services on them. There is no doubt that the completion of such a centralized administrative framework came with the establishment of the Taiho Ritsuryo nationwide law. However, the process of how it was created remains to be learned.

The family registration information on the unearthed wooden strip--which was made under the Asukakiyomihararyo legal code from the reigns of Emperor Tenmu and Empress Jito--includes words meaning "healthy male" and "soldier." This discovery proves that a military-draft system and taxation classification were already in force at that time--before the establishment of the Taiho Ritsuryo law. It also reveals that regional administrative offices regularly kept track of the movement of residents in local areas. [Source: Kazumasa Ikedam Yomiuri Shimbun, June 14, 2012]

Image Sources: 1) Ray Kinnane (futons, workmen, school kids, cell phone motorcooterm bike parking 2) Hector Garcia (sleeping), 3) Andrew Gray Photosensibility (kids playing), 4) Jun at Goods from Japan (hankos, train scene), 5) Photomann veding machine website (vending machine, honor-system shop), 6) xorsyst blog (bento), 7) Yokohama city (recycling)

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013