SUMO WRESTLERS AND SUMO LIFESTYLE

Sumo wrestlers are called “rikishi”. They wear a top knot, a hair style that dates back to the 1600s, and have special names like Musoyama (“Two Battling Mountains”), Takamiyama (“View From Lofty Mountain”), Asahiyata (“Bounteous Morning Sun”), and Konoshiki (“Delicate Embroidery”). Some wrestlers adopted name derived from the name of their sumo master or the place of their birth, Many names end with -yama (mountain), -gawa (river) or -umi (sea). Wrestlers are not supposed to keep their ring names after they retire. The names technically belongs to the stable. Over the years, it is not unusual for different wrestlers from different generations to have the same name.

About 680 wrestlers belong to the Japan Sumo Association. In public, sumo wrestlers are expected to be self-effacing, modest and soft-spoken. They have to wear kimonos and keep their hair in a well-oiled top-knots. They also have to compete throughout the year and do not have several months off like athletes in other sports have.

The sumo lifestyle for top wrestlers is not all that bad. They get fame, women, all the beer they can drink and the right to eat as much as they want and take a long nap in the afternoon. Occasionally wrestlers are involved in scandals with their coaches or beautiful actresses. When there are no major tournaments, sumo wrestlers tour the country, appear in single-day tournaments, sing karoake at charity events, make guest appearances on game shows, and practice, work-out and eat.

Much of the sumo lifestyle is centered around encouraging humility. After wrestlers retire, they often do a stint working as security guards or ushers at the arenas where the tournaments are held. Riskshi are supposed to be embodiments of Japanese virtue: dignity, honor, strength and discipline. They are expected to remain stoic, express only humility and garniture in interviews and never showboat after winning or expressing disappointment of they lose. Any expression of joy and petulance is frowned upon.

Riskshi have traditionally been deeply loved and respected by many people. One former wrestler told Time. “When we visit retirement homes, old people like to touch us and sometimes are brought to tears. There’s something spiritual about sumo. “

Websites and Resources

Links in this Website: SPORTS IN JAPAN (Click Sports, Recreation, Pets ) Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUMO RULES AND BASICS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUMO HISTORY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUMO SCANDALS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; SUMO WRESTLERS AND SUMO LIFESTYLE Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FAMOUS SUMO WRESTLERS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FAMOUS AMERICAN AND FOREIGN SUMO WRESTLERS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MONGOLIAN SUMO WRESTLERS Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Good Websites and Sources: Nihon Sumo Kyokai (Japan Sumo Association) official site sumo.or ; Sumo Fan Magazine sumofanmag.com ; Sumo Reference sumodb.sumogames.com ; Sumo Talk sumotalk.com ; Sumo Forum sumoforum.net ; Sumo Information Archives banzuke.com ; Masamirike’s Sumo Site accesscom.com/~abe/sumo ; Sumo FAQs scgroup.com/sumo ; Sumo Page http://cyranos.ch/sumo-e.htm ; Szumo. Hu, a Hungarian English language sumo site szumo.hu ; Books : “The Big Book of Sumo” by Mina Hall; “Takamiyama: The World of Sumo” by Takamiyama (Kodansha, 1973); “Sumo” by Andy Adams and Clyde Newton (Hamlyn, 1989); “Sumo Wrestling” by Bill Gutman (Capstone, 1995).

Sumo Photos, Images and Pictures Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Interesting Collection of Old and Recent Photos of Wrestlers in Competition and in Everyday Life sumoforum.net ; Sumo Ukiyo-e banzuke.com/art ; Sumo Ukiyo-e Images (Japanese-language Site) sumo-nishikie.jp ; Info Sumo, a French-Language site with Good Fairly Recent Photos info-sumo.net ; Generic Stock Photos and Images fotosearch.com/photos-images/sumo ; Fan View Pictures nicolas.delerue.org ; Images from a Promotion Event karatethejapaneseway.com ; Sumo Practice phototravels.net/japan ; Wrestlers Goofing Around gol.com/users/pbw/sumo ; Traveler Pictures from a Tokyo Tournament viator.com/tours/Tokyo/Tokyo-Sumo ;

Sumo Wrestlers : Goo Sumo Page /sumo.goo.ne.jp/eng/ozumo_meikan ;Wikipedia List of Mongolian Sumo Wrestlers Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Asashoryu Wikipedia ; Wikipedia List of American Sumo Wrestlers Wikipedia ; Site on British sumo sumo.org.uk ; A Site About American sumo wrestlers sumoeastandwest.com

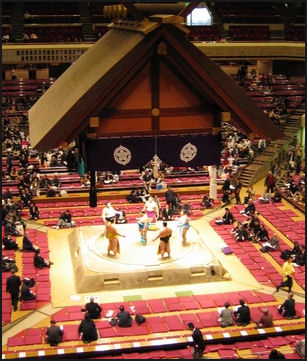

In Japan, Tickets for Events, a Sumo Museum and Sumo Shop in Tokyo Nihon Sumo Kyokai, 1-3-28 Yokozuna, Sumida-ku, Tokyo 130, Japan (81-3-2623, fax: 81-3-2623-5300) . Sumo ticketssumo.or tickets; Sumo Museum site sumo.or.jp ; JNTO article JNTO . Ryogoku Takahashi Company (4-31-15 Ryogoku, Sumida-ku, Tokyo) is a small shop that specializes is sumo wrestling souvenirs. Located near the Kokugikan national sports arena, it sells bed-and bath accessories, cushion covers, chopstick holders, key chains, golf balls, pajamas, kitchen aprons, woodblock prints, and small plastic banks — all featuring sumo wrestling scenes or likenesses of famous wrestlers.

Rules for Sumo Wrestlers

Sumo wrestlers enjoy less personal freedoms than athletes in other sports and arguably live the most restricted lives of all athletes. Their daily routines lives are defined by austerity and strict rules and they are expected to be subservient to their stablemasters (coaches), with younger wrestlers expected to be subservient to their seniors.

Wrestlers are taught that sumo is not just a sport: it is a way of life with its own etiquette that has to be respected. James Hardy wrote in the Daily Yomiuri. “Sumo is special because it codifies and prioritizes respect — respect for one’s opponent and respect for one’s position within the sport’s’s hierarchy.” Matches begin with a bow and end with a bow. One former wrestler said, “The dohyo is a sacred place where gods descend. It isn’t just a ring — and wrestlers must act accordingly.

The Hawaiian yokozuna Akebono once said, "Sumo is very much a vertical society, so when I joined at 18, there some kids who were 15 or 16 who'd joined before me. So no matter how much I beat them up in the ring, afterward they'd still make me scrub the toilets and bathtub."

Sumo wrestlers are not supposed to drive according to Japan Sumo Association rules. The wrestler Kyokutenho was suspended for a tournament and demoted to the juryo division in April 2007 after he was involved in a minor traffic accident, Another wrestler, Toki , was banned from several tournaments when he killed somebody in a car accident. In recent years some wrestlers started to demand that they be given the right to drive, saying that not being able to, especially when one has children, is a tough burden.

After a series of scandals broke in the later 2000s all sumo wrestlers were required to attend a series of demonstrations and lectures on correct ring technique, etiquette, behavior on regional tours and “regular common sense for everyday life.”

Sumo Stables and Support Groups

Sumo training centers are known as stables and coach-trainers who run them are known as stable masters. The wrestlers live at the stables — combination gym, training center and dormitory — and are taken care of by the stablemaster (“oyakata”) and his wife. Describing life in the stable, yokozuna Musashimaru told the Japan Times, "It is a group, it's a family. It's a brother thing. We only have one lady in the house and one man, We call them mum and dad.” Wrestler’s failures are often blamed on the stablemasters.

An “oyakata”(stable master), himself a retired wrestler, manages one of the roughly 50 “heya”(stables) in Japan and oversees a half dozen to 30 or more wrestlers The stablemasters collectively form the Japan Sumo Association (JSA), the main sumo organizing body. They receive payments from the national association for each wrestler in their stable. There is a lot of pressure for stables to keep wrestlers because they are a source of income.

Wrestlers are required to live and train at their stables for the duration of their careers. Changing stables is forbidden. Members of the same stable don't wrestle one another unless they are tied for the lead at the end of a tournament. This has caused some controversy when one stable has a lot of good six wrestlers, which gives them an advantage because they don't have to fight one another but the other wrestlers have to fight them all.

Out of more than roughly 700 wrestlers who are members of a stable, only about 70 presently qualify for “sekitori”status. The few who make it to the top divisions usually marry and live outside the stable, but for most, the stable is the only home a young wrestler will know for most of his sumo career. Many are forced to retire due to sickness or injury, and it is rare that a wrestler would compete beyond his early thirties.

There were 53 stables as of 2008. The largest ones have as many as 30 wrestlers. The smallest have only one. Some stables were founded in the 19th century. The Isegaham stable was founded in 1859. Most stables are located in the quiet business district near Kokugikan in Ryogoku in Tokyo and are usually supported by associations of rich patrons. To open a new stable, a wrestler need buy the necessary “toshiyori kabu” (sumo leader stock), which reportedly cost around $2.5 million.

Sumo wrestlers and stables have special supporters called a “koenkai” (supporters group). These group are very powerful and supportive. If a wrestler wants to get married he is expected to get permission from the Koenkai. Akebono's koenkai disbanded while he was a yokozuna’something that normally just doesn't happen — because he didn't inform the leaders in his group soon enough when he got married.

Sumo Apprentices

chores Novice apprentices join the stables at around the age of 15 when many of them are surprisingly skinny and some are ex-juvenile delinquents. Typically, apprentice wrestlers — more often from a rural part of the country than a city dweller — are scouted while still in junior high school. If their family agrees, they move away from their homes at live at the stables and are taken care of by the stablemaster's wife, as if she were their mother. Before joining many wrestlers attend sumo school.

The youths train, eat, and sleep communally in the stable and receive a small allowance. Members of the same stable do not compete against each other in regular tournament play. The life of a sumo apprentice is demanding and even the most promising young men usually require five years or longer to reach the higher ranks and begin to receive a salary as a “sekitori”(professional) . The apprentices train hard, learn techniques from their coaches and perform chores for senior wrestlers such as doing their laundry and washing their backs in the shower. They are also bullied to develop mental toughness and endurance, and spend long hours meditating in front of Shinto shrines placed on mounds on sand in the middle of the dohyo to improve concentration.

Life for the lowestranked wrestlers is rigorous. They rise as early as 4 or 5 o’clock in the morning, put on their “mawashi”, and begin “keiko”(practice). They are also obliged to run errands for the higher-ranked wrestlers. The latter enjoy the privilege of sleeping later. Describing his apprenticeship, one wrestlers wrote: "First it was yelling, then pushing and caning with a broom while they ordered me to do this exercise and that. Finally I was on the ground and the treatment continued. I was bullied pretty thoroughly, during which the senior wrestlers attitude changed back and forth between severity and laughing amongst themselves about what a joke it was."

Sumo Daily Routine

relaxing During a typical day wrestlers wake up at 5:00am and train from 5:30am to 11:00am, have breakfast-lunch and then take a long nap. Lunch is eaten in order of rank, followed by a session with a topknot hairdresser. After a nap of a couple hours, the wrestlers do household chores and do another workout. After that they relax, watch television and read until they eat dinner. From about 7:30pm to 10:30pm the wrestlers have free time and then it lights out, with wrestlers sleeping in the same room together.

A daily session of “keiko”ends around noon, upon which the wrestlers sit down to a brunch consisting of a special stew called “chankonabe”(a high-calorie stew containing various kinds of meat and vegetables), condiments, pickles, and several large bowls of rice, often washed down with one or two bottles of beer. (Wrestler’s appetites are legendary.) Following this large meal, the next several hours are usually spent napping, which along with the large quantities of food facilitates weight gain. Through this regimen of exercise, diet, and sleep, it is not unusual for some wrestlers to weigh more than 150 kilograms, and a few tip the scales at 200 kilograms and higher.

The heaviest training takes place in the morning. Some of the youngest wrestlers begin their training at 4:00am or 5:00am. The senior wrestler usually being later. Yokozuna Musashimaru told the Japan Times, "I get up about 7 o'clock and by 8 I'm down here in the practice ring...After training I'll stretch out some more, warming down, before hitting the showers and having lunch." Sometimes he trains in the afternoon. Sometimes he doesn't. "After lunch it’s time for the afternoon nap. Often I can't sleep so I'll just hang around, watch some TV or listen to music. Or I'll take a walk around the neighborhood. When I'm out I wear my yukata but around the house it's casual: jeans or shorts. Then at 3 o'clock, everyone helps clean the house...the 30 of us have to share all the chores. Then sometimes I'll spend some time in the weight room, probably three times a week, but otherwise my day is done and I can do whatever I want...If' you're home, everyone gets together for evening meal at about 6 o'clock, but I'll usually go out."

Life in the stable is often determined by rank and age. The senior wrestlers often get to shower first, have their meals served to them, eat on special cushions and chose what they want to watch on television. The younger wrestlers often act as their servants.

Tournament Routine

Musashimaru said, "Two or three days before your first bout, you're trying to put your mind in the ring. Then you try to get your body to the point where its there as well...Everything is different on tournament days. It's al much faster-paced, more upbeat. The morning training session is lighter than usual and I have to make sure I get sleep after training even though I don't want to. It’s both mental and physical rest."

"During a tournament, we usually eat later, around 7 o'clock, and after that the younger kids go out to sing karaoke or to the video-game arcade, and I'll have a few beers, but there's a curfew is we can't go too far. I'm allowed to stay out until 11:30pm, but the younger ones have to be in by 10:30pm. Some of them are only 15. Even at 9 o'clock the stable "father" is checking up on the kids to see if they’re back."

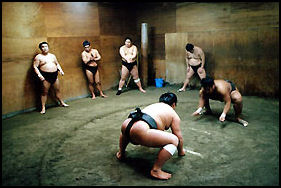

Sumo Training

Training for the senior wrestlers consists of practice sessions called “keiko”, which in turn consists of performing endless repetitions of “teppo” (thrusting exercises) and “shiko” (leg stamps) and other exercise. For “shiko”, the wrestler raises his legs alternately as high as possible. During “teppo,”opened palms slap continuously against a wooden pillar. “Matawari”is an exercise in which one sits with legs spread as wide as possible.Sometimes the wrestlers do pushing and shoving drills and wrestle with other members of their stable. A common routine is for a wrestler to stand at the center of the dohyo and take on all comers. Some do weightlifting.

Sumo drills include leg stomps, moving forwards while barely lifting upward-turned feet, and standing stationary absorbing charges from other wrestlers and pushing an inert wrestler from one side of the ring to the other. Sumo sparring features a junior wrestler repeatedly smashing himself against a senior wrestler. Because it is so intense wrestler rarely do the sparring for more than three minutes. The wrestlers are often covered in sand and sweat and the enclosed training rooms smell like a locker room left to rot.

training Musashimaru told the Japan Times, "I always start the same way, Shiko are the sideways leg lifts; you have to get your breathing right and lift each leg as high as possible in turn. Then I' do matawari, sitting on the clay floor and spreading my legs as wide as possible, then leaning forward until my cheek is in the dirt. Then it's the wooden “teppo” pole, which in practice your hands move against, slapping and pushing...To end the warm-up, I'll work on my start, my dash across the ring.”

"By the time training is done at about 10:30, you've really worked up a sweat...I'll sweat off six kilograms in the morning session alone. And I never eat breakfast. The morning workout is so tight that if you did it after eating you'd be sick; often you're sick anyway because it so physically demanding.”

Sumo drills such as leg stomps and standing stationary absorbing charges from other wrestlers have been adopted to rugby training,. New Zealand, All Black winger Mike Cron, who has spent time with the New York Giants and Japanese sumo wrestlers, told the Daily Yomiuri, “Sumo wrestlers have incredible power and strength and explosiveness, which is very much what we want for the front row...We want to have the world’s best scrum and we want to have the fastest engage.”

Occasionally wrestlers die during training. A wrestler died in practice at the Sadogatale stable in 1992. In 1990, the top division wrestler Ryukozan died after training ay Dewanoumi stable.

Training for Young Wrestlers at Sumo High

Saitama Sakae high school boasts the No. 1 high school sumo team and has trained the sons of yokozunas and ozekis. There kids as young as 12 do leg squats series, heave 320 kilogram tires, slap wooden pillars with their open palms and do other exercises. Blood is often visible in wrestling sessions. “Every day of sumo practice is like a traffic accident,” Saitama Sakae high school coach Michinori Yamada told Time.

Time is made to teach the spiritual side of the sport and the history of sumo. Yamada told Time, “Sometimes I just cancel practice and talk about sumo’s traditions and culture instead. There is an elegance to the whole tradition. That’s what gives it a Japanese essence.”

Yamada told Time, “You look at the Mongolians who come up today, and they have the hungry, strong bodies of kids who grow up doing hard labor on the farms. Japanese families used to send their boys to sumo stables to make sure they got enough food, Now, Japanese kids eat what they want, they go to college, and they don’t want to work so hard.” There are Japanese 12-year-olds that weigh 105 kilograms, and have breasts and thighs that chafe when they walk.

Sumo Hazing and Bullying

more training Punishment and humiliation are intrinsic parts of sumo training. Wrestlers who have been deemed as not hard working enough are beaten by senior wrestlers with fists and bamboo poles and even metal shovels. Those that retreat are hit harder and taunted by the other wrestlers. Yokozuba Asashoryu who has been accused of whacking fellow wrestlers on the head with bamboo poles told the Los Angeles Times, “You have to be strict to make them try harder.”

Young wrestlers have routinely been beat with wooded sticks and metal baseball bats.Such beatings are called “kiai-ire” (“instilling spirit”) in the sumo world and are said to be aimed at preventing injury during tournament bouts. A survey in 2007 by the JSA of 53 stables found that 90 percent of them had used baseball bats or similar tools in training. About a third said bullying and hazing occurred during training. Many in the sumo world defend the practices, saying the are vital to making the wrestlers tough.

Hazing is called “cherishing” in the sumo world. On the rough practices, ozeki Kaio said, “Practice has always been tough. I was slapped around...but only because my stablemaster wanted to make me strong. It wasn’t bullying..It’s partly because of such training that I was able to become strong. It’s thanks to such harshness that I am where I am now.”

See Death of 17-Year-Old Wrestler, Sumo Scandals.

In May 2008, stablemaster Magaki and veteran wrestler Toyozakura had their salaries cut by 30 percent for three months for caning and beating a junior wrestler with a bamboo sword and striking him with a ladle and causing a head injury that required eight stitches to mend. Wrestlers are not always the victims. In October 2007, a the stablemaster at the Musashigawa stable was charged with beating a cook at the stable with bamboo broom because the 20-year-old cook hit a 19-year-old wrestler on the head with a stick.

Sumo and Eating

relatively small

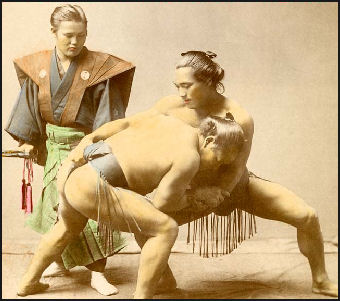

19th century sumo wrestler Some sumo wrestler consumes 20,000 calories a day. Most of the calories come from eating two huge daily meals of “chankonabe”, washed down with beer and sake. They also eat a lot of fruit, much of it is given to the stable by fans and supporters.

Each day a typical wrestler eats a kilo of rice and chanko, supplemented by fried chicken, potato salad, grilled fish, barbecued pork, str-fried vegetables, simmered squash, noodles and salad. According to the book “What I Eat: Around the World in 80 Diets” by Peter Menzel and Faith D’Aluisio, a typical sumo wrestler eats 3,500 calories a day, which isn’t so different from the daily caloric intake of a Brazilian grandmother.

Chankonabe is a thick protein-rich, chicken-based soup seasoned with soy sauce, miso and sake ingredients that vary from stable to stable but usually consists of fish, seafood, cabbage, mushrooms, burdock, onions, carrots, leaks and other vegetables. Most of the protein comes from chicken and tofu. It is eaten with rice.

Chankonabe is often cooked up by the sumo wrestlers themselves and made with chicken not red meat because chicken is considered good luck and sumo wrestlers have traditionally shied away from meat from animals with four legs. One wrestler told the Daily Yomiuri, "We eat chankonabe day after day. Sometimes we get a bit tired of it and wish we had more variety."

Musashimaru said he likes to eat out in the evening. "The problem is that restaurants think I'm going to eat a whole cow. They give me a slab of meat when all I want is a small piece...2 kg of meat” Give me break ! People thinking I'm going to eat everything on the menu."

Sumo and Weight

There is no weight limit in sumo. Top-ranked wrestlers average around 350 pounds and the heaviest ones weigh between 500 and 600 pounds. The average weight of sumo wrestlers increased about 70 pounds between the 1970s and the 1990s. The average weight of top level sumo wrestlers in 1999 was 156kg, up from 126kg in 1974.

Konishki in the 1980s Many fans complain that the emphasis on size has ruined the sport, with bulk not technique deciding the outcome of most bouts. Many wrestlers miss tournaments due to injuries caused by their weight.

In the 1990s, the chairman of the Japan Sumo Association complained that wrestlers were getting too fat. "Some young wrestlers are too heavy to keep up with the training," he said. "They're breathing heavily all the time. Some even have trouble walking."

In 2000, the Japan Sumo Association announced that it would require wrestlers to have their body fat content periodically checked with wrestlers regarded as being too obese advised to go on a diet.

Hair and Spiritual and Mental Aspects of Sumo

A wrestler’s elaborate, coiffured top-knot hair style is called the “oicho mage”. A wrestler’s hair is a symbol of his strength, It grows along with his strength and became a sign of seniority and is dramatically cut off when a wrestler calls it quits.

Sumo has quasi-religious quality and a strong sense of propriety summed up by the word “hinkaku” (“a sense of dignity and grace”). According to Sho Sakaigawa, the most influential person in the Japan Sumo Organization, "The way of Sumo teaches rikishi the correct etiquette and how to build character. By following the way of Sumo, one is cleansed." At training sessions visitors are not supposed to talk.

Japanese novelist and sumo aficionado Akiyuki Mosaka told Time, if the wrestlers "admit they're strictly entertainment, their entire world will fall apart...This is the “tatemae” [façade] and “honne” [hidden truth] of sumo."

Most top wrestlers maintain that sumo is more mental than physical. "Your toughest opponent in sumo is always yourself," yokazuna Takanohana told the Washington Post. "Making yourself stand up to the daily pressure of 15 straight days is the hardest thing in the sport."

Yokozuna Akebono told National Geographic,"People see these big fat guys tossing each other around the ring, and it's hard to understand that this is a mental sport. But the mental side, the spiritual side, is a lot more important than the body. If you can't get yourself in the right frame of mind intellectually, you can't win."

Sumo Ranking

19th century sumo wrestlers There are about 900 active wrestlers in professional sumo and each one is assigned a specific numerical standing within a complex system of rank set by the Japan Sumo Association, which controls the sport. Most wrestlers never make it beyond the lower and middle ranks.

There are two divisions of elite, salaried wrestlers: “Juryo” is the lower of the two; “makunoichi” (or”makuuchi”) is the upper division with about 40 wrestlers. Within Makunoichi there are five ranks: “yokozuna” (highest rank), “ozeki” (second highest rank), “sekiwake” (third highest rank), “komusubi” (forth highest rank), “maegeshira” (fifth highest rank).

Who a wrestler fights and when in the tournament he does it is determined by rank. Television announcers often use the wrestlers rank instead of his name. During one tournament Reid heard one announcer say, "The ninth-level new entrant has the second sub-champion in a dangerous spot!"

Names changes are common in sumo. Some change their name to a legendary name in their stable when they reach a high rank

Ozekis and Yokozunas

former ozeki Chiyotaki

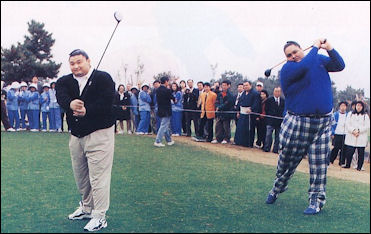

goofing around

Ozekis (champion) are second highest ranking below yokozuna. There are generally between three and seven ozekis at any one time. Their monthly salary is around ¥2.32 million a month.

Wrestlers are appointed to ozeki if they do consistently well or win one or two major tournaments. Winning more than 33 wins bouts in three consecutive bashos and beating good wrestlers with good, powerful technique them is the usual criteria for being named an ozeki. Having two losing records is enough to have ozeki status taken away. But former ozeki in such a position can earn his ozeki status back with 10 wins in the next bout.

The highest honor that can be obtained in sumo is yokozuna, or grand champion. In the 400 year history of organized Sumo only 69 wrestlers have achieved the coveted title. Their monthly salary is around ¥2.82 million a month.

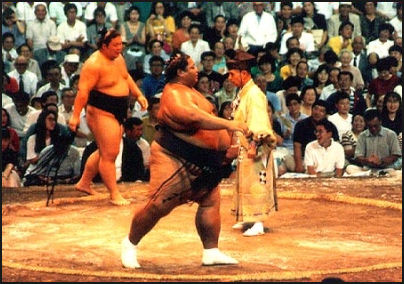

"Yokozuna" literally means "horizontal rope," a reference to the rope a yokozuna wears around his waist when he performs his ring entering-ceremony, which he does accompanied by two sword-carrying wrestlers from his stable, to start each tournament.

If an ozeki win several major tournaments he is appointed to is to yokozuna. To become a yokozuna a wrestler generally has to win bouts in a row and carry himself in a proper way in he ring. If a yokozuna has a losing record or displays poor form, he has to retire. Ozekis often have a reputation for floundering when yokozuna promotion is at hand.

Yokozuna Ritual

the unryu, the yokozuna belt

The decision to name a new yokozuna has to be approved by the Yokozuna Deliberation Council and the Japan Sumo Association ranking committee. After the decision is announced to the new yokozuna’s stable, the new yokozuna is taught the ring ceremony in preparation for a performance at Tokyo’s Meiji Shrine,

During the special dohyo-iri purification ritual at Meiji Shrine the new yokozuna is presented with a ceremonial rope belt and certification of rank. The yokozuna ring ceremony is performed for 15 straight days. The white rope and ceremonial apron that accompanies it have combined weight of 30 kilograms.

For the ceremony the new yokozuna needs a sword, often valued at $200,000 or more, a set of three ceremonial aprons, There are two ceremonies: The shiranau style in which the rope is knotted in a double bow and the yokozuna adopts an offensive pose. The style is believed to be unlucky because many of those who performed were unsuccessful yokozuna.

Decisions on the choices of yokozuna and other matters concerning the champions is made by the Yokozuna Deliberation Council. The council has one female member Makiko Uchidate

Sumo Salaries and Poor Treatment of Lower-Ranked Wrestlers

Akebono and Takanohana

playing golf John Gunning, author of the Daily Yomiuri column Inside Grip, called the sumo world a “feudal system that pays no salary to nine out of 10 of them.” Wrestlers below the juryo division get a monthly stipend of about ¥60,000 ($700) — about five percent of the $12,000 a month a juryo division wrestler makes.

“Sumo holds up the “Heaven and Hell” distinction between juryo and makushita as the ultimate motivating factor for rikishi,” Gunning wrote. “However, many wrestlers get married, have children and take out a mortgage when they become sekitori. It's unrealistic to expect them to take a 97 percent cut in salary and go back to sharing a room with 20 other wrestlers if they drop down in rank.

Junior wrestlers must act as servants for their seniors and spend an inordinate of time scrubbing toilets. One wrestler told Time, “It was difficult until I got used to this life. The seniority system is absolute.” Many argue that the sumo lifestyle has to be made less severe if the sport wants to attract young people to the sport. A good start might be allowing wrestlers to drive.

Sumo, Retirement and Injuries

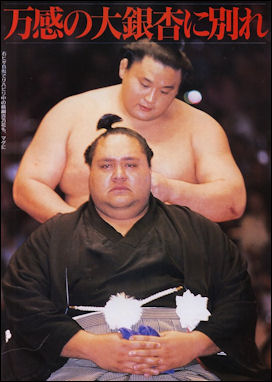

Takanahona cutting Akebono's

at Ake's retirement ceremony

When a wrestler retires he is feted to a tearful ceremony in front of a large crowd called a “danpatsushiki” in which other wrestlers and invited guest take turns sniping away the wrestlers locks of hair and climaxing when the wrestler’s stable master cuts his topknot which means he is no longer a sumo wrestler anymore.

Often celebrities and politicians take part. Scores of small snippets are made, usually around the sides. The stable master of the wrestler cuts through the heart of the top knot and removes it and hold it up sort of like an executioner holding up a head. After that the wrestlers listens to short testimonials, bows in all four directions and retreats to hi dressing room.

After they leave sumo wrestlers give up their names. For a while they work as ticket takers, ushers and security guards at sumo tournaments as an expression of humility. Even yokozunas have to do this. Retirement pay outs are given based on career wins.

Many wrestlers never graduate from high school. They devote their life to sumo training when they are teenagers, spend their career rising through the ranks and retire around the age of 30 or 35, when they either become a coach, start their own stable, or lose weight and launch a new career. Many retired wrestler find work in the stables or open restaurants that serve chankonabe (the soup that sumo wrestlers eat).

Common sumo injuries include dislocated shoulders and elbows, incurred when falling out of the ring, and knee problems caused by bearing so much weight and falling ir moving in awkward ways during a bout. Some wrestles are so fat they develop serious liver problems at a young age. Leg injuries have became more common as the wrestler's leg muscles are not strong enough to carry their bulks and the massive bulk of their opponents. If a wrestler suffers from a leg injury he is wheeled away from the dohyo in large wheelchair specially-made for wrestlers.

Image Sources: Nicolas Delerue and Japan-Photo.de expect Konishki (Japan Zone) and 19th century wrestlers (Visualizing Culture, MIT Education), teh last four are from Sumo Forum

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013