KIMONOS AND JAPAN

furisode “Kimonos” are a traditional Japanese robe. “Kimono? literally means “something to wear.” It only came to describe the elaborate garments we know today in the 19th century, when Western clothes were first widely worn and a word was needed to distinguish Japanese clothes from Western ones.The women’s kimono is a long loose robe shaped like a capital “T” worn tightly around a woman’s body with a thick sash-like belt called an “obi”. It has loose sleeves and is classified by how wide the opening is at the wrist. In the old days there were small sleeve kimonos (“kosode”) and large sleeve kimonos (“osode”) but since the Edo period they have pretty much been of a standard size.

Today, kimono have become much less common a sight in Japan. They are, however, worn by some elderly people who have been used to kimono since their youth, waitresses in certain traditional restaurants, or people who give instruction in, or take lessons in, traditional Japanese arts and customs such as Japanese dance, the tea ceremony, or flower arranging. Kimono are, compared to Western clothing, troublesome to wear and do not lend themselves to physical activity; thus they have virtually disappeared as a practical, daily-life type of dress. That said, kimono are nonetheless rooted in the life of the Japanese people and are worn on certain important occasions. Events at which women wear kimono include “hatsumode “(the first visit to shrines or temples in the new year), “seijinshiki “(ceremonies feting young people’s reaching the age of twenty), university graduation ceremonies, weddings, and other important celebrations and formal parties. On such occasions, girls and unmarried women wear “furisode”, or kimono with long sleeves, whose attractive designs are a fine example of one of the many aspects of traditional Japanese culture that continue to flourish. [Source: Web-Japan, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Japan]

Everyday kimonos have traditionally been made of cotton while those worn on special occasions were made of silk. New silk kimonos with all the accessories cost between $10,000 and $100,000 dollars and can cost $2,000 just to rent for single day. Rich women buy their own kimonos. To save money, ordinary women try to borrow kimonos from family members or friends, buy used ones or rent them when they need them.

Many Japanese women shy from wearing kimonos because have a reputation for being expensive and difficult to take care of and put on. But that doesn’t have to be the case. The cost problem can be dealt with by buying used kimonos at markets or on Internet auctions. Cotton or polyester robes are light and machine washable. The obi problem can be dealt with by getting a tsukeobi — the equivalent of clip on tie. For footwear some women recommend ¥3,000 urethane-soled zori sandals which are comfortable and easy to walk in.

The swishing sound made by a woman in a kimono is described with the Japanese words “shu, sha” and “kyu”. The sound of an obi being tied is “kuku kuku”." It is said that a kimono “echos the way the heart beats" and a woman is more gentle when she wears a silk kimono," Kokoh Moriguchi, a textile artist and one of Japan's revered living treasures, told National Geographic. "That may be why men like women to wear silk kimonos."

Good Websites and Sources: East West Kimono Galleries eastwestkimono.com ; Japanese Kimono japanesekimono.com ; JP Net Kimono Hypertext web.mit.edu/jpnet/kimono ; Kids Web Japan web-japan.org/kidsweb ; Kimono Source kimonosource.com ; Kyoto Kimono kyotokimono.com ; Book: “Kimono: Fashioning Culture” by Liza Dalby (1993) is a history and cultural study of the kimono. On Japanese Clothes Good Photos at Japan-Photo Archive japan-photo.de ; Japanese Kimono.com japanesekimono.com ; Tomboco.com tomboco.com.au ; Traditional Crafts of Japan — Weaving kougei.or.jp/english ; Short Piece on the Clothes of Japan adrianaallen.com/blog ; Japan -Shop.com japan-shop.com ; Men’s Online Conversion of Japanese, European and American Sizes onlineconversion.com ; Women’s Online Conversion of Japanese, European and American Sizes onlineconversion.com ; Museums and History Japan Costume Museum iz2.or.jp/english ; Historical Clothing yusoku.com/english ; Tokyo National Museum site tnm.go.jp ; Kyoto National Museum kyohaku.go.jp ; Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum bunka.ac.jp ; Sengoku Daimyo sengokudaimyo.co Links in this Website: JAPANESE CLOTHES Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE SILK Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; FASHION IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ;

History of Kimonos

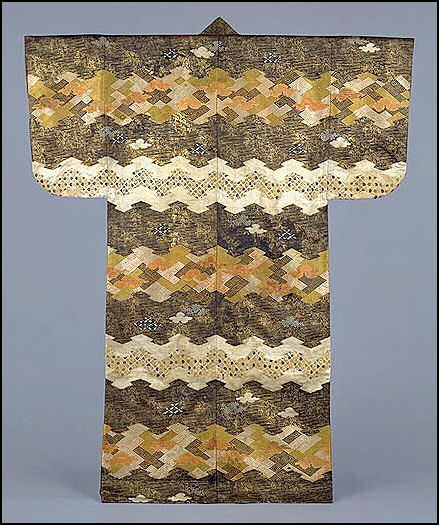

Kimonos date back at least to the 10th century. They began as copies of the undergarments of Tang dynasty Chinese robes and were originally worn as undergarments by nobility and work clothes by ordinary people. The kimono became the traditional garment of the Japanese in the 15th century and the main features — full sleeves, doubled front and long collar — have changed little since they were first conceived. In some cases nobles wore as many as a dozen kimonos, each exposing a piece of the one underneath it.

17th century kosode

In the Edo Period, laws were imposed on the merchant class that prohibited the wearing of kimonos with elaborate embroidery. To get around these laws merchants developed innovative techniques to decorate clothes. In the most important of these techniques, “yuzen” dyeing, rice paste was applied to the clothes like a stencil for color. Lovely, complex designs were achieved by changing the patterns of the rice paste and using different colors.

Kimonos remained as everyday garments for ordinary Japanese women until after World War II, when they began wearing more and more Western clothes. Kimonos were thus relegated to formal wear worn at special occasions. Christal Whelan wrote in Daily Yomiuri: “While the switch to modern Western dress began for Japanese men much earlier — in the Meiji era — Japanese women did not give up the obi-cinched kimono until the post war period. The reason for this gender discrepancy is partially explainable in aesthetic terms — women had much more to lose than men by giving up the traditional dress.”

Kimono Features

Women's kimonos essentially all have the same design. They consist of at least a dozen parts: a flat collar, and eight panels, two each for the back and front, and four for the sleeves. A properly worn kimono is tucked right under left (left under right is worn by corpses in coffins) and is tightly sealed shut with the stiff, three-meter-long obi. No buttons of zippers are used for fastening. Women usually wear an underkimono beneath their kimono.

What distinguishes one kimono for another is color, pattern and the quality of the material. Patterns are usually made of silk or cotton and the basic material of best quality kimonos is a 39-foot-long piece of linen that is wetted, stretched across the snow and bleached in the sunlight.

Traditionally, a kimono shoppers selected a roll of fabric, was carefully measured and had the kimono custom sewn. Each piece was sent to a special craftsman who irons it before it is sewn into a kimono. Customers often had to wait a long time before the kimono was finished. Labor costs are the main reason why kimonos cost so much.

A roll of cloth about 13 yards long and 15 inches wide is enough to make one kimono. Unmarried women wear a long sleeve kimono (“furisode”) . When they get married the sleeves are shortened. Children’s kimonos are made with tucks along the shoulders and waist that are let out as the child grows. A “haori” is a short coat. It is sometimes lined and is worn over a kimono for formal occasion or when outside.

Obis

On the three main types of obis, Christal Whelan wrote in Daily Yomiuri: “The most formal — the maru obi — made of the finest silk brocade, has a single seam sewn along its length that gives it a double thickness, and measures 420 centimeters in length and up to 68 centimeters in width when folded. However, its uncomfortable weight, stiffness and astronomical cost are the main reasons for its present scarcity. The fukuro obi shares the same dimensions as the maru obi but is lined with a mildly contrastive material. In this way, it is often reversible with plain silk or satin on the opposite side. Shorter than the other two, the Nagoya obi is folded over and stitched to make it easy to wear. Its convenience and brighter color palette appeal to young women and it is among the most popular obi on the market today.”

On the history of obis Whelan wrote in Daily Yomiuri: “the female-oriented obi industry promoted the sash to cult status among Japanese women. Fasteners of coral or porcelain came to embellish the outer cord that held the obi in place. Tiny cushions filled out bows, and elaborate motifs of birds, flowers or trees stood out against a brilliant background of metallic thread. The manufacturers, designers, dyers and weavers responsible for obi production steadily refined the techniques originally imported from Korea and China in the eighth century. For hundreds of years the obi was fussed over so that both its size and position vacillated — tied in front, on the side or in the back. During the 18th century, there were more than 20 ways to tie the obi so it could convey age, status and availability much in the same way Spaniards once used the silent language of the fan.” [Source: Christal Whelan, Daily Yomiuri, May 8, 2011]

“By the mid-Edo period (1603-1867), the obi's length and width had finally become standardized, as did its position. The rear style had proven itself the most stable, perhaps because of the increasing weight and bulk typical of the most ornate silk brocades. The obi had definitely become the centerpiece of the outfit, not only in the physical sense as the point that drew the eye's attention and divided the woman's body into two nearly equal parts, but because a single kimono could be worn with several different obi to convey various seasons or social messages. In this way, a collection of obi could vastly extend a limited kimono wardrobe.”

“Now, just when it seemed the obi had gone to join the miyako kingfisher (no longer seen in Japan's skies), recycled obi have started to turn up in various guises in the West. Sometimes they have been transformed beyond recognition and called into new service as decorative accents in homes. They lie stretched across slabs of mahogany as table runners. They are resewn into bedspreads, or refashioned into men's evening vests for a night at the opera. They adorn couches as cushion covers, and women are enjoying them as summer corset-tops. For dramatic effect, they are draped over bamboo rods and used as window treatments. They hang vertically from doors, are suspended from walls and wind around banisters of once-barren staircases. The fukuro obi twisted in a loose spiral and placed in a glass tube becomes a stunning centerpiece. In Honolulu, Anne Namba Designs specializes in "kimono couture," or garments made from vintage kimono and obi. The designer's clients have included Mikhail Baryshnikov and the late Elizabeth Taylor.”

Putting on a Kimono and Obi

simple obi Kimonos are complicated garments. Women often need lots of time and the help of a professional to put one on. Skilled do-it-yourselfers can put on their kimonos in about 30 minutes. Less skilled do-it-yourselfers need an hour and half, even after taking kimono-donning lessons.

Under a kimono wears one-size-fits-all undergarments, a “susoyoke”, a floor-length apron; a “hadajuban”, a short jacket that wraps around the waist; and a “nagajubanm “,a longer robe that goes directly underneath the kimono.”

An obi is a sash-like belt that holds the kimono in place and truss up the body in an erect position. A curved board gives the obi its shape, An obi can be tied in different ways, often depending on the occasion and the age of the wearer. The length and width varies according to the material. The Nagoya style is tied in the pack in a special bow.

On of the hardest thing about putting on a kimono is getting the obi right. Traditional obis are held in place with strings. These days some come with velcro patches that hold them in place.

Wearing a Kimono

rose obi Kimono wearing is also very complex. Certain occasions calls for certain fabric, certain season, particular colors. They are specific ways to sit, walk and bow when wearing a kimono to make sure the garment stays unwrinkled and all the parts remain in place.

Wearing a kimono is supposed to be good for your posture. Walking with an obi keeping your back straight on traditional geta sandals has been likened to tip-toeing with bricks on your feet. When moving around women are supposed to walk slightly pigeon-toed and take tiny shuffling, steps within the confines of the kimono.

Michelle Green, who paid ¥15,000 for a kimono-wearing lesson in Kyoto, wrote in the New York Times,”By the time I was suited, my breasts and hips (which had been padded) had disappeared. I had lost my freedom of movement: to sit, I found myself sinking onto my shins like a camel; rising required pushing back on my heels and unfolding like a lotus. I did well enough with those bits, but only because they felt like familiar yoga postures...Learning to swish noiselessly while trussed, however, obviously required more than one lesson. I was told to step light but deliberately on the tatami mat.”

One Japanese woman told The New Yorker, “I could never get use to wearing kimonos in daily life. They are too available for one thing, and uncomfortable. Many actions and walk change when I wear them, and like most people, I prefer Western clothes.”

The owner of a kimono store told cultural anthropologist Ofra Goldstein-Gidoni; "When I wear Western dress like today, I have a feeling of activity and moving. Kimono, on the other hand gives one a feeling of calmness and an urge to quit work. Life now is very busy in Japan, but when a girl wears kimono it gives her the opposite feeling."

When it is not worn a kimono is folded in a special way and stored in a drawer. Silk kimonos are carefully cleaned. Often times the stitching is removed and each piece was washed separately and then the resewn.

Yuzen

steps in Yuzen dying “Yuzen” is a resist dying technique invented in Kyoto in 1600s. It creates an intricate waterproof and washable design of minutely intricate detail on the kimono while preserving its suppleness. The art form is named after Miyazaki Yuzen (1681-1763), an artist monk who painted fans developed the unique yuzen method for painting clothing. Yuzen art is still very much alive as an art form in Kyoto. [Source: Judith Thurman, October 17, 2005, The New Yorker]

Once a garment is ready a yuzen painter sketches his designs freehand on to the fabric with a fine brush dipped on a soluble ink made from a small blue wildflower. When the ink dries the kimono is taken apart and stretched over ribs of bamboo. Various material are used for resists — wax starch, paper, wood — which protects an area from being dyed.

Once a garment is ready a yuzen painter sketches his designs freehand on to the fabric with a fine brush dipped on a soluble ink made from a small blue wildflower. When the ink dries the kimono is taken apart and stretched over ribs of bamboo. Various material are used for resists — wax starch, paper, wood — which protects an area from being dyed.

Yuzen painters usually use rice paste for resist which is squeezed through a brown mulberry paper cone waterproofed with persimmon tannin. The diameter of nozzle defines the thickness of the resist. It it possible to reduce the thickness to the width of a hair. The underside of the silk is sprayed with water to dissolve the soluble ink and to increase the absorbency of the rice paste.

Kimonos As Works of Art

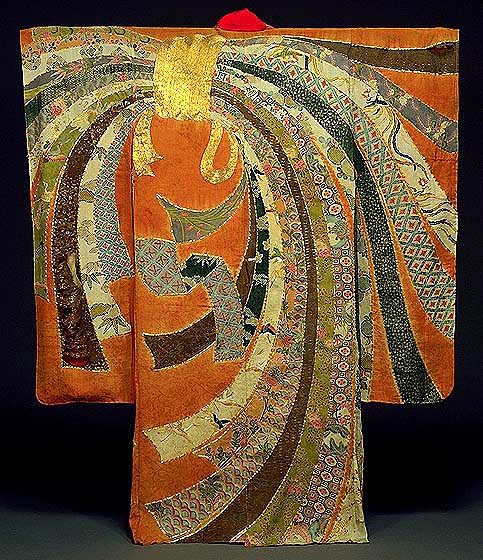

Japanese textile artist Itchiku Kubota singlehandedly revived the 350-year-old art of “tsujigahana”, an elaborate method of decorating fabric with tie-dying, paint brushing, ink drawing, gold-leaf application and embroidery. Born in Tokyo in 1917, he said he was drawn to the art at the age of 14 when he saw a garment made of elegantly patterned cloth in the Tokyo National Museum and was so taken with its beauty he stared at it for three hours. "In a sudden moment," he told Smithsonian magazine. "I encountered a source of boundless creativity which revealed to me my calling."

18th century yuzen-dyed kimono

Kubota has spent most of life working on a series of 75 elaborately decorated kimonos called the "Symphony of Light" that when hung side by side produce a "panoramic tapestry celebrating the four seasons and the cosmos." Each kimono takes about a year to make and many of them boast 300 colors and cloth that is repeatedly tied, dyed, steamed, rinsed and stretched again and again up to 100 times. Kubota said he would have to live to 120 to finish the project. As of 1995, Kubota had finished 30 of the 75 kimonos.

Kunihiko Moriguchi is regarded as a master of “yuzen”. His creations often take months to complete and cost between $40,000 and $80,000. His typical client is a successful businesswoman in her 40s. The typical one owns four of creations. About 10 percent of his clients are non-Japanese.

Yuzen-dyed kimonos made by Moriguchi and his father Kako (1909-2008) have been declared national treasures. The two artists are known for combining traditional kimono-making methods with decorative techniques that are normally used by lacquerware craftsmen.

Unlike some yuzen painters who like ramie or cotton, Moriguchi prefers white crepe spun by Chinese or Brazilian silkworms and woven in Japan. He makes his own dies from scratch using material such as indigo, shell powder, onion slin, cochineal, insect shells, and ground minerals. His specialization is using zinc pellets mixed with rice paste and fixed with wood wax and soy juice to create “makinori” designs, which were first observed by his father — an even greater master than Moriguchi — in kimonos found in Tokyo National Museum and replicated after 15 years of trial and error research.

Decline of Kimonos

Fewer and fewer women are wearing kimonos and fewer still are buying them. In one survey, 70 percent of young women asked said they were interested in learning to wear a kimono but few actually have the time to do it.

Kimonos are not common sights but they are seen often enough on subways and in train stations, especially on holidays and weekends. They are generally only worn by women to mark big events such as weddings and holidays like New Year's or worn by women who run traditional businesses such ryokans and tea houses. Few office ladies wear them.

The kimono industry is having a hard times. It began declining in 1980s as women int luxury clothing shifted the interest to Western styles. During the recession in the 1990s, few women had the money they could blow on a new kimono. Between 1990 and 1998, sales of kimonos dropped by 30 percent. In 1998, on average, two kimono companies went bankrupt every month.

Revival of Kimonos

kimono fashion show In an effort to revive the kimono industry, kimonos are being made with cheaper synthetic materials, offered in ready-to-wear varieties, and worn in offbeat ways with skirts, jackets and scarves. One company has released a zip-up kimono that greatly reduces the hassle of putting a kimono on. Other companies sponsor kimono parties, kimono vacations and kimono donning classes.

In Tokyo and some other cities there are kimono clubs made up of women who like to wear kimonos and teach others how to appreciate them and put them on.

In recent years the kimono industry has become more automated. Some kimono makers relay on computers and ink jet printers rather than stencils, paintbrushs and manual labor. Kimono makers are offering a wider range of designs and selling their stuff on the Internet. One of the main appeals of these advances is the money saved. Kimonos made using modern methods are available for less than $600. There is also a big business in second hand kimonos. Fashionistas like them for their colors and patterns and they are much cheaper than new ones.

Kimono shops are trying to attract new customers with new designs and material such as camouflage patterns and denim and offering suggestions about wearing them in unconventional ways, with velor overcoats and scarfs. Women on the street have been seen wearing kimonos with capes and sneakers; men have been spotted wearing traditional men’s kimonos with turtle-neck sweaters. There is also a movement to make kimonos from cheaper materials so they are more affordable.

Drumming Up Kimono-Wearing Opportunities

Mieko Furuoka wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: “They're so cool, but there's never an opportunity to put one on! For people who lament the few occasions to step out in kimono, several events have been held to provide more opportunities to wear the traditional Japanese garment. [Source: Mieko Furuoka. Yomiuri Shimbun, December 7, 2012]

On a midautumn weekend, five men and women in kimono met at Nishijin-ori textile manufacturer Kyogei in Kamigyo Ward, Kyoto. It was their first time to meet. This meeting was organized by online site Ichiri Mall, which began holding "Kimono de Odekake" events (events for kimono wearers) in July. The website is run by Saitama-based kimono store Ichikura Co. In response to complaints of kimono fans lamenting the lack of occasions to wear them, the website launched the event to foster friendships through kimono. Every month, such events are held at museums and other facilities.

"I began itching to wearing kimono in summer," said writer Saeko Tsuruhara, 39. She worked part-time at a ryokan when she was a student and can put on a kimono by herself. "I don't have friends to hang out with in kimono. Today, I had a great time with like-minded people," she said. Atsushi Murakami, 41, who works at a school, became interested in kimono about five years ago. "I choose kimono or other outfits depending on the mood on my days off," he said while exchanging contact details with other participants. For beginners interested in casually enjoying kimono on a budget, a rental and dressing service might be the way to go.

At the end of September, a "moon-viewing and sake-tasting party for adult women" was held at Ramada Osaka hotel in Kita Ward, Osaka. The organizer prepared a plan through which kimono could be rented and fitted for 3,000 yen. Among 70 participants, six used the service, and were "transformed" in 15 minutes. Mai Kuki, 32, who came with her coworker, chose a mauve kimono. "I felt like I became a new me. I stand straight, like 'Yamato nadeshiko,'" Kuki said, referring to an elegant Japanese woman of traditional beauty and kindness.

Kimono Ricca school and shop's Akiko Yoshizawa helped Kuki don the kimono. She said many kimono today can be washed at home and have a variety of textiles and designs that suit the tastes of young women. "Wearing kimono while having lunch or shopping with friends is a wonderful way to spend the day," Yoshizawa said. "I want more people to go out and have fun in kimono.”

With its rich history and culture, Kyoto may come to mind first as the ideal place to take a stroll in kimono. Wearing a kimono in the ancient capital can bring some added benefits, too. A free 80-page Kyoto Kimono Passport is issued by the Kimono no Niau Machi Kyoto management committee every year. The committee is organized by the Kyoto prefectural government and the kimono and tourist industries. If kimono wearers show the passport to any of about 400 selected temples, shrines and restaurants, they receive special offers and discounts. The passport also lists places that can help adjust and fix kimono that become loose. The passport is available at a tourism information center and other places, as well as via this website (www.kimono-passport.jp/) or mail if you pay the postal fee. Call (075) 256-6830 for more details.

Image Sources: 1), 4), 5) MIT Education, 2) 8) National Musuem in Kyoto, 3) JNTO, 6) 7) , Association for the Promotion of Traditional Crafts Industries in Japan 9) Ray Kinnane

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2013