AKIRA KUROSAWA AND HIS FILMS

Akira Kurosawa (1910-1998) is generally regarded as one of the greatest film directors of all time. Two of his films — “The Seven Samurai” and “Rashomon” — are considered all time classics, and a third, “Blood on the Throne”, was described by poet T.S. Eliot as his favorite movie of all time.

Martin Scorsese once said, "Passion. Dynamism. Force. Exhilaration. Speed. Terrible beauty. These are among the many words that come to mind when I think of Kurosawa's cinema." Francis For Coppola once suggested that Kurosawa should be the first film maker to be given the Nobel prize.

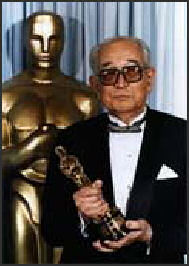

In 1990, Kurosawa was presented with lifetime achievement Academy Award by American directors George Lucas and Steven Spielberg. Spielberg later said, "He was the visual Shakespeare of our time. He is the only director who right until the end of his life continued to make films that were, or will be, recognized as classics...He was a celluloid painter — he was as close to an impressionist as you can get in film.”

Websites and Resources

Books and DVDs: Kurosawa's memoir is titled “Something Like an Autobiography” (1978); “The Films of Akira Kurosawa” by Donald Ritchie is one of the best books on Kurosawa. The BBC did a documentary “Kurosawa” by Adam Low. All of Kurosawa’s works are available on DVD. Good Websites and Sources: TCM Data Base on Kurosawa tcmdb.com/participant ; Akira Kurosawa News, Information and Discussion akirakurosawa.info ; Good Collection of Kurosawa Images and Clips kurosawa.jokerman.net ; Akira Kurosawa Foundation kurosawa-foundation.com ; Kurosawa Films on DVD jactari.free.fr/Akira_Kurosawa ; Posters and Movie Descriptions edogawa-u.ac.jp ; British Film Institute on Kurosawa bfi.org.uk/features/kurosawa

Links in this Website: JAPANESE FILM Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; CLASSIC JAPANESE FILMS AND FILMMAKERS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; AKIRA KUROSAWA FILMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; GODZILLA Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILM INDUSTRY Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; MODERN JAPANESE FILMMAKERS AND FILMS Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; JAPANESE ACTORS AND HOLLYWOOD ACTORS IN JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan ; HOLLYWOOD FILMS ABOUT JAPAN Factsanddetails.com/Japan

Books: “A Hundred Years of Japanese Film” by Donald Richie (Kodansha International, 2002); “Japanese Cinema — An Introduction” by Donald Richie (Oxford University, 1990). Good Websites and Sources on Japanese Film: Google e-book: A Hundred Years of Japanese Film by Donald Richie books.google.com/books ; Midnight Eye midnighteye.com ; Japanese Movie Listing lisashea.com/japan ; Kinema Club pears.lib.ohio-state.edu/Markus ; Japan Association for the International Promotion of the Moving Image unijapan.org/en ; Toei Uzumasa Movie Land is a theme park and movie studio were many samurai and historical drams have been shot. Website: Japan Guide japan-guide.com Asian Film Asia Society on Film asiasociety.org ; iFilm Connections — Asia and Pacific asianfilms.org ; Love Asia Film loveasianfilm.com ; Senses of Cinema sensesofcinema.com ; Illuminated Lantern on Asian Film illuminatedlantern.com

Databases, Directories, Links: Internet Movie Database /www.imdb.com ; Directory of Interent Sources newton.uor.edu ; Japanese Film Resources at the University of Iowa lib.uiowa.edu/eac/japan ; Tokyo International Film Festival tiff-jp.net ; DVDs Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com ; Japanese, Chinese and Korean CDs and DVDs at Zoom Movie zoommovie.com ; CD Japan cdjapan.co.jp ;

Kurosawa's Early Life

scene from Drunken Angel Kurosawa was born near Tokyo on March 23, 1910. He was the seventh child of military officer who came from a samurai family and woman who came from a merchant family. His father was very strict. He dotted loving attention on his samurai sword and scolded his wife because she didn't do things the samurai way.

Kurosawa once wrote, "It seems I come from a line that is overly emotional and deficient in reason." When he was young he had a dream that he was standing on one side of train track and his family was on the other side. A dog went back and forth delivering messages between him and his family. A train came along and cut the dog in half. The dog's death reminded Kurosawa of a fresh tuna being cut. He was unable to eat tuna for 30 years after that.

Kurosawa was regarded as cry baby by his schoolmates. He flunked his military physical in 1930. Inspired by van Gogh and Cézanne, he originally wanted to be a painter but gave up this ambition after concluding there was nothing remarkable about his style. He then showed an interest in literature but he wasn't very good at that either. Kurosawa's interested in painting and Western literature would appear in his films. He liked to work out his films with storyboards.

Kurosawa's Hobbies and Character

Kurosawa smoked late into his life. One of his greatest passions other than film was food, which he liked to be good quality with few ingredients. Among his favorite dishes were shabu-shabu with sliced pork and leafy vegetables, steak with miso paste and garlic, and soba.

Kurosawa enjoyed reading and playing golf in his free time. When he died his son placed a golf club in his coffin. He painted through his life and often created images and painted storyboards to go along with his films that often appeared more like works or art than illustrations.

Kurosawa once gave the following advise: “Everybody, find something you really love. I advise you to look for something that is truly important to you, something that matters and has most significance to you. Once you find it, try to channel all your energy into it.”

Kurosawa's Film Career

Kurosawa gets an Oscar Kurosawa drifted into films, with the help of his older brother, a silent film narrator, almost as an after thought. He entered film about the time that silent movies were being replaced by talkies. He worked for a while as an assistant director, and directed his first film, “Sugata Sanshiro” (1943), about "a rowdy young judo expert," at the of age 32. The film was almost banned by censors who considered it too "British-American."

In World War II, Kurosawa directed nationalist films, such as “The Most Beautiful” (1944), a blatant piece of propaganda that supported Japan's war effort. Drunken Angel (1948), made after the war with actor Toshiro Mifune, is regarded as the first true Kurosawa film.

Kurosawa didn't receive much acclaim outside of Japan (or much in Japan either) until his film “Rashomon” won the Venice Film Festival Grand Prize and an Academy Award for Honorary Foreign Language Film Award in 1951 (the Oscar for Best Foreign Film had been created yet). Even though the film had been panned in Japan as boring as too "Western," the award transformed Kurosawa into a major figure almost overnight. His reputation was confirmed when “Seven Samurai” won the Silver Lion at the Venice film festival in 1954.

Kurosawa's Style

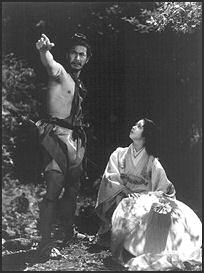

sceen from Rashomon Kurosawa has been called the most eclectic director that ever lived. He was a master of huge battle scenes and psychological dramas, equally home in castle of feudal Japan as he was on streets in post-World War II Tokyo. He made a connection between westerns and samurai films as well as between Shakespeare and shoguns.

Chinese director Zhang Yimou wrote in Time:"Like Stanley Kubrick, he had the artistic strength to resist compromise, either political or commercial. His own producers often didn't understand his films, which often gained attention at home only after receiving international accolades. Kurosawa had sporadic commercial difficulties...As a cinematographer, I was awed by Kurosawa’s filming a grand spectacle, particularly battle scenes. Even today I can not figure out his method. I...found that he used only 200 or so horses for certain battle scenes that suggest thousands. Other filmmakers have more money, more advanced techniques, more special effects. Yet no one has surpassed him."

Terrence Rafferty wrote in the New York Times: “When you think of Akira Kurosawa, you think, most likely, of swords and flags, of castles under siege, of men in dark armor and women in brilliant kimonos, of horses galloping to battle in driving rain. The movie that brought Kurosawa — and Japanese cinema as a whole — to the attention of the world, “Rashomon” (1950), was set in the distant past, and practically all the most celebrated films of the remaining 40-plus years of his career were historical dramas, too: “The Seven Samurai” (1954), “Throne of Blood” (1957), “Yojimbo” (1961), “Sanjuro” (1962) and “Ran” (1985). [Source: Terrence Rafferty, New York Times, December 30, 2009]

The 1949 urban noir “Stray Dog,” in which there isn’t a horse or a castle in sight, and where the weapon of choice is a Colt pistol, sometimes catches audiences by surprise. “It shouldn’t,” Faffert wrote. “Of the 30 movies Kurosawa directed, better than half tell stories of present-day Japan, and a fair number of them, including “Stray Dog,” rank with his greatest works. In a way Kurosawa’s modern-day films (the Japanese call them gendai-geki, to distinguish them from jidai-geki, historical films) reveal more of that almost messianic streak in his nature, his serene determination to remake the world — or at least to show the strange, turbulent process of its remaking....The gendai-geki...contain some of Kurosawa’s most inventive filmmaking, and some of his most provocative reflections on the human condition in the last, violent century. “Ikiru” (1952) and “The Bad Sleep Well” (1960), for example, are remarkably trenchant examinations of the mid-century ills of bureaucracy and big business.

Kurosawa as a Director

scene from Seven Sanurai When he was on the set, Kurosawa often acted like a military commander. An assistant followed him around with a stool so he cold sit down wherever he stood. When he approached his actors they suddenly appeared to be busy. Some called him Emperor Kurosawa.

Yuzo Kayama, one of Kurosawa's actors wrote in Newsweek, "He was a perfectionist who studied everything about the period the story was to have taken place. In “Red Beard”, there was a scene of an old man, Rikusuke, dying. As usual, Kurosawa spent days studying how a man died — how he should breathe and how his eyes are supposed to look at the last minute of his life. He had his staff polishing the walls and corridors of the setting of a clinic very morning to get exactly the right feeling."

Describing what Kurosawa was like as a dinner guest, Kayam said, "Over supper and drinks, he talked about movies until 5 in the morning. From the start to the end, our conversation was all about movies and moviemaking, and nothing else. I realized once again how much Kurosawa loved movies. He used o say, 'If you take movies away from me, there will nothing left.'"

Kurosawa's Films

Scene from Redbeard Kurosawa made 30 films in 55 years. Most of them were historical period films with elaborate costumes, evocative landscapes, lots of action, complex narratives, exquisite details, and philosophical ruminating. Some of his films were quite violent and lyrical at the same time. When film changed from black and white to color Kurosawa held out for a long time.

Kurosawa most famous early films include: “Judo Saga” (1943, his first film), “Drunken Angel” (1948, about a moral hero in a corrupt society), “Stray Dog” (1950, with a villain like the hero and a story similar to DeSica’s “Bicycle Thief”), “Ikiru” (1952), “Rashomon” (1951), “The Seven Samurai” (1954), “Throne of Blood” (1957), “The Hidden Fortress” (a 1958 samurai film), “The Bad Sleep Well” (a 1960 social commentary) “Yojimbo” (a 1961 samurai film), “Sanjuro” (a 1962 samurai film), “High and Low” (1963, about a Yokohama-based factory owner who has ambitious plans comprised by a kidnapping), and “Red Beard” (a 1965 samurai film).

Kurosawa's films were influenced by Shakespeare (“Throne of Blood” was based on “MacBeth”, and “Ran” was based on “King Lear”), Gorki (“The Lower Depths”, 1957), Dostoevsky (“The Idiot”, 1951) and American Western films (many of his samurai films were like John Ford films with Japanese warriors instead of cowboys).

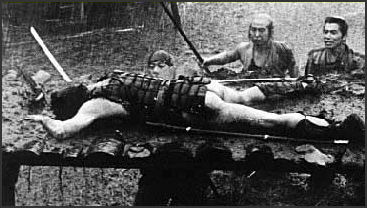

Classic moments from Kurosawa's film include the scene in “Throne of Blood”, when the monarch is struck with arrows and suddenly realizes he is going to die; the swift tracking shots through the forest in “Rashomon”; and the moment in “Ikiru” when the bureaucrat pleads with the young girl to show how to live and she says, "I only eat and work. I only make toys like this." The most memorable fight scenes in “Seven Samurai” were shot to look like they took place in the pouring rain.

Ikiru, Rashomon, Seven Samurai and Yojimbo

Many film critics regard “Ikiru” ("To Live") as Kurosawa's greatest film. Selected by Time magazine as one of the “All-Time 100 Movies,” it is about a petty bureaucrat who didn't learn how to live until he realized he was going to die soon of cancer and found fulfillment in the kindness of a young girl and decision to leave his mark on the world by creating a city park.

Rashomon is a period piece about an the rape and murder of an aristocratic women by bandits as seen from four conflicting viewpoints. Based by on a novel by Ryunosuke Akutagawa, it is a work that explored the meaning and perception of truth.

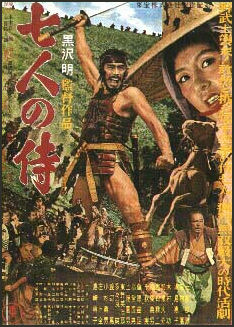

Kurosawa's most well known film, “Seven Samurai”, is over 3½ hours long. Set in the 16th century Japan, it about a small village, regularly attacked by bandits, that hires a group samurai to defend it. One of the most influential action films ever made, the plot revolves around the seven samurai, their battles and their acclimation to village life. The bandits are the barbaric bad guys, the villagers are innocents protected by the samurai using barbaric means. Much of the film revolves around the samurai getting along with villagers and the amount of action is relatively light with exception fo the climactic battle in the rain.

“Seven Samurai” has a special place in American film in that it was strongly influenced by John Ford Westerns, particularly “My Darling Clementine”, and in turn influenced John Sturges’s 1960 “The Magnificent Seven”, Howard Hawks’ “Rio Bravo”, Sergio Leone spaghetti Westerns as well as films by directors like Lucas, Spielberg and Scorsese.

“Yojimbo” is one of Kurosawa's most popular and amusing film. A black humor about samurai life selected by Time magazine as one of the “All-Time 100 Movies,” it follows the story of a samurai who stands alone against the world and single-handedly cleans up a town terrorized by bandits. “Sanjuro” is a lighthearted companion film that goes with “Yojimbo”. In this film the samurai teaches a group of younger samurai to fight against a stronger enemy.

Stray Dog

“Stray Dog” , Kurosawa’s ninth film, is a kind of police-procedural thriller, in which a young Tokyo homicide detective named Murakami (Toshiro Mifune) roams the crowded streets of the postwar city in search of his stolen gun,” Terrence Rafferty wrote in the New York Times. “At first he merely feels humiliated, but before long much more painful emotions take hold. He learns, to his horror, that his gun is being used to commit robberies: one woman is seriously injured; the next dies. Murakami, crazed with grief and guilt, combs the seedier quarters of the sprawling city, where everybody looks hungry and desperate, wearied by an unrelenting summer heat. He trudges through this unwelcoming terrain with the grim persistence of a soldier making his way home after a lost campaign.” [Source: Terrence Rafferty, New York Times, December 30, 2009]

“Murakami is in fact a veteran of his country’s disastrous recent war, and so, it turns out, is the criminal he’s tracking. His partner, a more experienced detective named Sato (Takashi Shimura), has to caution him not to feel too much sympathy for his prey. The young cop’s conflicted emotions generate an unusual sort of suspense, a heightened apprehensiveness. The world of “Stray Dog” is one in which anything can happen, in which people no longer know with any confidence how to act rightly: a world whose standards of behavior have become dangerously slippery. Murakami winds up wrestling with the killer, his criminal alter ego, in a muddy field, a place that doesn’t look like it belongs in a city — in civilization — at all. It looks a bit like the primeval forest in which the action of “Rashomon” takes place, that shadowy no man’s land of ambiguity and moral confusion.”

“And as in “Rashomon” the filmmaking in “Stray Dog” conveys an extraordinary sense of urgency, a fierce need to capture the complexities of human behavior while everything is still fresh and volatile. These are strikingly unsettled-looking movies, composed with care but betraying nonetheless a profound uncertainty about the forms society, and film, should take in the postwar world: nothing fixed or stable, everything at risk. You can feel Kurosawa’s excitement at the prospect of reinventing the conventions of his national cinema, and at the larger idea that the Japanese might have a chance, after long catastrophe, to reimagine themselves.”

No Regrets and Drunken Angel

Terrence Rafferty wrote in the New York Times: In “No Regrets for Our Youth” (1946), he had even allowed himself to entertain the possibility of a kind of back-to-the-land redemption for his shamed nation, and trotted out an impressive array of heroic Soviet-style cinematic techniques to drive the message home. “No Regrets” is a surprisingly affecting film, but it’s clear that Kurosawa isn’t wholly comfortable with either its simple moral solutions or its borrowed aesthetic. It took him only a couple more years to figure out a better way. In “Drunken Angel” (1948), which Kurosawa often referred to as his breakthrough, he devised a style that somehow combined the formal restraint of traditional Japanese cinema with the irreverence and nervous energy of Hollywood movies: it looked entirely new, like nothing else Eastern or Western. [Source: Terrence Rafferty, New York Times, December 30, 2009]

The drunken angel of the title is a gruff neighborhood doctor named Sanada (Shimura), who does bend the elbow rather too enthusiastically but is utterly dedicated to his patients’ health: a man who goes to great lengths to save even those who don’t seem worth saving, like the consumptive yakuza Matsunaga (Mifune, in his first film for Kurosawa). Although Matsunaga is a nightmarishly bad patient, with about as much respect for doctor’s orders as he has for the law, Sanada gives it his all anyway, scolding and cajoling and making rude remarks (putting his own well being, at times, in some peril). “Drunken Angel” is an unlikely mixture of soap opera and gangster movie, and although it’s less consistently electrifying than “Stray Dog,” it’s a very satisfying picture: Kurosawa’s style feels appropriate for the time and the place and characters, and redemption is achieved, believably.”

High and Low

And as much as I love “The Seven Samurai,” there are times when I think that the Kurosawa movie I’d take to the proverbial desert island would be his 1963 kidnapping thriller “High and Low” , Terrence Rafferty wrote in the New York Times, “That film, which is based on, of all things, one of Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novels, is also a police procedural, but to an even greater extent than in “Stray Dog” Kurosawa blows up the genre and puts the pieces back together in a completely new way. He begins with the moral dilemma of a businessman (inevitably, Mifune) deciding whether to pay the ransom for his chauffeur’s abducted son — an amount of money that would effectively wipe out his assets. This first part of the movie has a claustrophobic chamber-drama feel to it, with the camera roving through a single set, in long, long takes. [Source: Terrence Rafferty, New York Times, December 30, 2009]

But when “High and Low” finally gets out of the house, it’s there to stay, as the police track the kidnapper through hot, bustling Yokohama and take us into a real world that is, if anything, even more disturbing than the devastated Tokyo of “Stray Dog.” Although there’s more prosperity in evidence — the businessman’s modern house sits complacently on a hill — there’s more disappointment too, more class resentment and festering envy. The movie’s construction is eclectic, radical, counterintuitive: it changes focus as swiftly, and as exhilaratingly, as the climactic battle of “The Seven Samurai.” And like that film, “High and Low” is for all its jangly modernity about the struggle to survive. Some do, some don’t, in every time and every place. The movie ends with a scream that sounds almost primal. Even without the armor and the horses and the swords, Kurosawa always made films about history, because he knew that we were living it.

Kurosawa and Hollywood

Scene from Ran Kurosawa's films in turn influenced American action films. Seven Samurai inspired “The Magnificent Seven” as metioned before and “Return of the Magnificent Seven”. “Rashomon” became “The Outrage. Hidden Fortress” provided the basic story line for “Star Wars” by George Lucas.

“Yojimbo” influenced “Shane” and “High Noon”. The spaghetti Western “A Fistful of Dollars” is a nearly shot-for shot remake of “Yojimbo” and the nameless drifter played by Clint Eastwood owes his career to the samurai played by Toshiro Mifune. Once when Eastwood was asked to comment on scenes of Mifune scenes dispatching bad guys with a sword quicker than Eastwood could with his gun, Eastwood was speechless. The 1999 film “Last Man Standing” is also based on the Kurosawa tale.

Although the subjects and themes of his films were largely Japanese, Kurosawa's genius was often better appreciated in the West than in Japan, where he was often accused of making films for foreign consumption.

Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune

Mifune Toshiro Mifune (1920-1997) is the actor associated most with Kurosawa's work. Born in China, he played stoic word-wielding samurai in many of Kurosawa's classics, including “The Seven Samurai, Yojimbo”, and “Rashomon”. Describing his first encounter with Mifune, who’d only been in Japan for a year, Kurosawa wrote: “A young man was reeling around the room in a violent frenzy. I was frightened as watching a wounded or trapped savage beast trying to break loose. I was transfixed.”

Mifune’s role as the drunken samurai-bandit in “Rashomon” is regarded by Chinese director Zhang Yimou as the one of the most charismatic performances of the 20th century, as good as anything done by Marlon Brando or James Dean. Washington Post Film critic Stephen Hunter described him as a “scruffy, growly samurai, loping along in a cloud of dust, slapping at gnats and ticks, three weeks on the far side of a bath...When he stops scratching, his eyes narrow and harden, and his hands dangle ominously near the long blade sheathed in his grungy sash...When it happens. It happens fast. He’s a whirl of grace and purpose and lethargy.”

Mifune was equally good playing a zoot-suited, jitterbugging gangster in “Drunken Angel” (1948) and a homicide detective who loses his gun only to find it used in a murder in “Straw Dog” (1949). Altogether Mifune appeared in 126 feature films, including 16 Kurosawa movies and the Hollywood films “Hell in the Pacific” (1968) and “Midway” (1976), and 17 televison films, including “Shogun” (1980).

Mifune’s sidekick in several Kurosawa films was Takishi Shimura, a Kurosawa regular.

Book: “The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune” by Stuart Galbraith IV (Faber & Faber, 2002)

Kurosawa's Later Life

Scene from Dreams Kurosawa attempted suicide in 1971 but was unsuccessful. He reportedly tried to kill himself because he felt he let down three other film directors who joined him to start an independent film company. The same brother who had helped Kurosawa enter film was successful in his suicide attempt at the age of 27 after he lost his job to talking films.

After his suicide attempt in 1971, Kurosawa moved briefly to Russia and from then on was largely dependent on foreigners — like Spielberg, Lucas, Coppola, and Frenchman Serge Silberman — for funding. Many of his last films were not well received by critics.

Looking back on his career in 1985, Kurosawa said, "I just make up stories and film them. When I am lucky, the stories have a lifelike quality that makes them appealing to people, and the film is successful." In addition to directing, Kurosawa also wrote scripts for films he didn't direct and even produced a couple of television commercials, and appeared in one for Panasonic.

Kurosawa's Later Films

Film made by Kurosawa

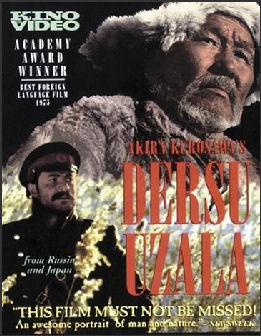

in the Soviet Union Kurosawa’s later films include: “Dodes'ka-den” (1970), “Dersu Uzala” (1975, made in Russia), “Kagemusha” (a 1980 samurai film with huge battle scenes), “Ran” (a 1985 samurai film), “Dreams” (1990, with eight dream episodes) and “Rhapsody in August” (1991, about the aftermath of the Nagasaki bombing), staring Richard Gere. “Ran” is modeled on the life of warring period warrior Mori Motonari.

“Kagenusha” is arguably the best of his later films. The first film he was able to make in Japan in 10 years, its is a medieval costume epic like Hollywood’s Ivanhoe and “Knights of the Round Table”. The film is about Shingen, a famous 16th century warlord and military technician and a thief that looks like him and learned to impersonate him. After Shingen is shot by a sniper the thief impersonates him for three years, When he is finally unmasked disaster results. The film features splendid costumes and spectacular battle scenes and was described by film critic Morris Dickstein as a film “about the power of images but also about the limits of that power.”

“Dersu Uzala” (“Dersu the Trapper”) is based on a book written by Russian geographer V.K. Areniev in the 1910s. The book and the film are about Areniev's guide, Dersu, who survived a horrible mauling by a tiger. The film won the Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award in 1975 for the Soviet Union not Japan. His last film “Madadayo” was one of his worst. Critics claim that his later films were overly sentimental.

Kurosawa died of a stroke at the age of 88 on September 6, 1998, three years after he fractured his spine and leg in a fall in a Kyoto hotel. He was preparing a film called “The Sea Was Watching” when he died.

Image Sources: YouTube, Bright Lights, Japan Zone, Realms of Cinema, Amazon

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Daily Yomiuri, Times of London, Japan National Tourist Organization (JNTO), National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2011